Abstract

Placental development is important for proper in utero growth and development of the fetus, as well as maternal well-being during pregnancy. Abnormal differentiation of placental epithelial cells, called trophoblast, is at the root of multiple pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, the maternal hypertensive disorder preeclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction. The ligand-activated nuclear receptor, PPARγ, and nutrient sensor, Sirtuin-1, both play a role in numerous pathways important to cell survival and differentiation, metabolism, and inflammation. However, each has also been identified as a key player in trophoblast differentiation and placental development. This review details these studies, but also describes how various stressors, including hypoxia and inflammation, alter the expression or activity of PPARγ and Sirtuin-1, thereby contributing to placenta-based pregnancy complications.

Keywords: Sirt1, PPARγ, placenta, trophoblast

Introduction

Placental Development

The placenta is a unique organ present only during intrauterine life, but contributing significantly to fetal growth and development [Burton and Jauniaux, 2015]. It is comprised of epithelial cells derived from the trophectoderm (TE), the outer layer of blastocyst, and of extraembryonic mesodermal (ExM) cells derived from the inner cell mass (ICM), the cells which give rise to the embryo-proper [James et al. 2012]. Over time, this combination of cells gives rise to an intricate organ, one that not only anchors the fetus within the uterine cavity, but also functions to provide the needed oxygen, nutrients, and hormones for fetal growth, and expel carbon dioxide and other waste. While the ExM gives rise to the mesenchymal portions of the placenta, including the fetal vasculature, the TE differentiates into two major trophoblast subtypes: villous trophoblast (labyrinthine trophoblast in mouse), involved in gas and nutrient exchange, and extravillous trophoblast (junctional zone in mouse), which anchor the placenta into the uterine wall and remodel maternal spiral arterioles in order to provide blood flow to the feto-placental unit (Figure 1) [reviewed in Soncin et al. 2015]. Abnormal development and/or function of this organ has significant consequences for both mother and baby, leading to complications ranging from gestational hypertension/preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction, gestational diabetes and macrosomia, to preterm delivery and stillbirth [Fisher, 2015]. In addition, more recent studies have shown that pregnancy complications, particularly those leading to aberrations in fetal growth, have a long-term effect, contributing to metabolic programming of the offspring and thus increasing the risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, later in life [Thornburg and Marshall, 2015]. This knowledge necessitates a deeper understanding of placental development, particularly pathways which can affect fetal growth. This review focuses on signaling pathways downstream of the nuclear receptor, PPARγ, and the protein deacetylase, Sirt1, and how these pathways, individually and in combination, affect both the development and the function of the placenta.

Figure 1.

Cartoon of trophoblast differentiation, indicating the role of PPARγ (A) or Sirt1 (B) expression and activation in the process. Terminology in parentheses refers to the mouse. Rosi=Rosiglitazone; Resv=Resveratrol. Arrow with circle at the end indicates an inhibitory effect on the indicated pathway.

PPARγ and Sirtuin-1

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) is a member of the family of ligand-activated nuclear hormone receptors, and a transcription factor known for its key role in glucose and lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation. Following dimerization with retinoid-X receptors (RXRs), PPARγ binds to specific DNA sequences termed PPARγ Responsive Elements (PPREs) and induces genes involved in fatty acid uptake and storage, leading to lipid accumulation and adipogenesis. In fact, PPARγ is required for formation of both white and brown adipose tissues, the former a site of energy storage and an endocrine organ, and the latter a site of energy expenditure and heat generation. PPARγ can be targeted using thiazolidinediones (TZDs), a family of synthetic agonists which are most commonly used in treatment of type 2 diabetes [reviewed in Park et al. 2008, and Koppen and Kalkhoven, 2010].

Sirtuin-1 (Sirt1) is a member of the NAD+-dependent family of protein deactylases and a nutrient sensor. Originally discovered in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as a gene able to regulate longevity, Sirt1 was first identified as a histone deacetylase, promoting chromatin compaction and hence silencing the genome in times of nutrient deprivation [reviewed in Giblin et al. 2014]. Since then, studies in mammalian systems have identified numerous non-histone targets of this deacetylase, including p53, FOXO1, and PPARγ. Notably, Sirt1 induction leads to PPARγ repression, thus inhibiting adipogenesis and enhancing fat mobilization, with the reverse phenotype shown by RNAi-induced Sirt1 downregulation [Picard et al. 2004]. In addition to metabolism, Sirt1 has been found to influence numerous other pathways, including those involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, and inflammation [reviewed in Knight and Milner, 2012 and Simmons et al. 2015]. Sirt1 can be targeted by the naturally-occurring compound, resveratrol, which has been identified as an anti-inflammatory agent and anti-oxidant, as well as by synthetic small molecules [Farghali et al. 2013].

While the negative regulation of PPARγ by Sirt1 has been the most well-studied, the relationship between these two proteins is by no means simple. A recent study has shown that Sirt1-mediated deacetylation of PPARγ leads to recruitment of a co-activator, Prdm1, and selective activation of PPARγ to promote “browning” of white fat [Qiang et al. 2012]. In addition, PPARγ can also be an upstream negative regulator of Sirt1, both by binding and inhibiting its deacetylase activity and by reducing its transcription [Han et al. 2010]. Finally, both the TZD class of PPARγ agonists and the Sirt1 inducer resveratrol have off-target effects, with TZDs inducing transient Sirt1 overexpression [Wei et al. 2010], and resveratrol identified to also bind nuclear receptors in the PPAR family, including PPARγ [Calleri et al. 2014]. Thus, evaluation of cross-talk between pathways regulated by these two proteins warrants careful experimentation and interpretation of results, particularly when using the common agonists.

In this review, we will focus on the role of the Sirt1-PPARγ axis in the placenta, with additional focus on trophoblast, the epithelial compartment of the placenta. We will begin by detailing the role of each protein during placental development, and to the extent known, in trophoblast differentiation. Next, we will discuss how these pathways are modulated in placental disease, particularly those associated with the stressors, hypoxia, oxidative stress, inflammation, and hyperglycemia. Throughout, we will also address the cross-talk between these two pathways (when known), as well as the therapeutic potential of targeting these pathways in placenta-based complications of pregnancy.

PPARγ in trophoblast differentiation and placental development

The gene for this protein is located on mouse chromosome 6 and human chromosome 3; in both species, alternative splicing gives rise to multiple isoforms, but the most ubiquitous isoform and the one abundantly present in the placenta as well as in all trophoblast subtypes is PPARγ1 [Barak et al. 1999]. Knockout of this gene in mice first revealed its importance in placental development: in its absence, embryos did not survive past midgestation [Barak et al., 1999; Kubota et al., 1999], and embryonic lethality could be rescued by either wild-type tetraploid aggregation [Barak et al. 1999] or by generation of an epiblast-specific knockout, using Sox2-Cre mice [Duan et al. 2007], indicating that placental defects are the basis for the embryonic phenotype. In fact, PPARγ was expressed in the placenta, beginning at embryonic day E8.0, prior to its expression in the embryo-proper (at E14.5) [Barak et al. 1999]. Evaluation of PPARγ-null placentae showed defects in labyrinth formation, with a thickened chorion persisting at E10.0, just after chorio-allantoic fusion should have taken place [Barak et al. 1999]. To dissect out the role of PPARγ in the trophectoderm compartment, we derived trophoblast stem cells (TSC) from littermate wild-type (WT) and PPARγ-null blastocyst-stage (E3.5) mouse embryos [Parast et al. 2009]. PPARγ-null TSCs grew slowly, and showed altered differentiation in vitro, with a complete lack of labyrinthine trophoblast markers, instead showing significantly elevated markers of junctional zone (spongiotrophoblast and trophoblast giant cells/TGCs); in fact, functionally, differentiated PPARγ-null TSCs invaded Matrigel in greater numbers than differentiated WT-TSCs [Parast et al. 2009]. Reintroduction of the gene into PPARγ-null TSCs partially restored the differentiation phenotype, inducing formation of syncytiotrophoblast and decreasing the number of cells able to invade Matrigel (Figure 1a) [Parast et al. 2009].

The important role of PPARγ in trophoblast differentiation and placental development is also highlighted by studies using agonists. In vitro, treatment of mTSC with rosiglitazone shifted differentiation toward the labyrinthine lineage, and inhibited trophoblast invasion; these effects were absent in PPARγ-null TSCs, indicating they were PPARγ-dependent [Parast et al. 2009]. Similar findings have been noted in human trophoblast, both primary extravillous trophoblast and the HIPEC65 cell line, with agonists inhibiting invasion in a concentration-dependent manner [Fournier et al. 2007]. Interestingly, synthetic (troglitazone, a TZD), but not naturally-occurring PPARγ agonists (15deltaPGJ2), enhanced differentiation of primary term cytotrophoblast (CTB) into syncytiotrophoblast (STB), both as assessed morphologically and by hCG secretion [Schaiff et al. 2000]. Another TZD, rosiglitazone, was found to affect the secretory function of human trophoblast differentially, enhancing transcription of hCG alpha and beta subunits and hCG secretion in villous trophoblast but inhibiting the same in extravillous trophoblast [Handschuh et al. 2009]. Overall, these data suggest that the effects of PPARγ activation on trophoblast differentiation are similar between mouse and human, with enhancement of villous/labyrinthine trophoblast, and inhibition of extravillous/junctional zone trophoblast, differentiation and function (Figure 1a). The effects of PPARγ activation on placental development in vivo have also been evaluated, albeit to a lesser extent: continuous treatment with rosiglitazone between E10.5 and E18.5 led to a reduction in both the thickness of the spongiotrophoblast layer and in labyrinthine vasculature, resulting in smaller WT, but not PPARγ-heterozygous, embryos and placentas [Schaiff et al. 2007]. In the same study, rosiglitazone also enhanced fatty acid accumulation in the placenta, but not in the embryo [Schaiff et al. 2007].

Limited data are available regarding PPARγ targets specific to the placenta and trophoblast. Perhaps the most well-characterized is the mucin, Muc1, which localizes to the apical membrane of labyrinthine trophoblast, facing the maternal sinusoids [Shalom-Barak et al. 2004]. Muc1 expression is lost in PPARγ-null placentas and induced following rosiglitazone treatment of WT mTSC [Shalom-Barak et al. 2004]. Muc1-null placentas show dilated maternal sinusoids with occasional blood “lakes,” indicating that its expression is required for proper placental function [Shalom-Barak et al. 2004]. Our own study pointed to Gcm1, a master regulator of villous/labyrinthine trophoblast differentiation, as a gene downregulated in the absence of PPARγ [Parast et al. 2009]. A more recent study has provided evidence for Gcm1 as a potential direct target of PPARγ in the human choriocarcinoma cell line, BeWo, during induction of syncytialization [Levytska et al. 2014]. But perhaps the most thorough study of PPARγ targets in the placenta has been performed by Shalom-Barak et al. [2012], in which they used microarray-based RNA profiling to evaluate genes altered in both placentas and TSCs in the absence of PPARγ. Surprisingly, the vast majority of genes identified in this manner had not been identified as PPARγ targets in other organs; in addition, a significant proportion (40%) of the differentially expressed genes were similarly altered in RxRα-null placentas, confirming this protein to be a main PPARγ partner in the placenta [Shalom-Barak et al. 2012]. Finally, since the bulk of the target genes were functionally linked to metabolism, rather than differentiation or development, the authors come to the thought-provoking conclusion that the severe phenotype of the PPARγ-null placenta indicates that proper trophoblast differentiation is tightly linked to metabolic function [Shalom-Barak et al. 2012].

Sirt1 in trophoblast differentiation and placental development

Similar to PPARγ, Sirt1 is ubiquitously expressed in both the mouse and human placenta [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2006; Lappas et al. 2011]. However, the phenotype of Sirt1-null embryos is more heterogeneous than PPARγ-null embryos, ranging from mid-to-late embryonic lethality to early postnatal lethality in inbred strains, depending on the genetic background of the mice [Cheng et al. 2003; McBurney et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2008]. Nevertheless, a common phenotype among all strains appeared to be fetal growth restriction. Based on this observation, we obtained Sirt1-heterozygous mice on the Sv129 inbred background from Dr. McBurney’s group, and set out to evaluate this embryonic phenotype in more detail [McBurney et al. 2003]. We observed embryonic lethality of Sirt1-null embryos at E13.5, confirmed their fetal growth restriction, and observed that the placentas associated with these embryos were also small [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2017]. Further histologic evaluation and in-situ hybridization for various trophoblast markers revealed abnormalities in both the labyrinth and junctional zone. We therefore proceeded to derive WT and Sirt1-null TSC, again from littermate E3.5 embryos. In the absence of Sirt1, TSC grew slower, but the primary phenotype was that of blunted differentiation, with reduction of both labyrinthine and junctional zone markers [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2017] (Figure 1b). In fact, both in vitro and in vivo, Sirt1 deficiency led to an accumulation of an Epcam+ trophoblast progenitor population; this was accompanied by elevated levels of cMet, a receptor tyrosine kinase which is required for maintenance of this labyrinthine progenitor cell population [Ueno et al. 2013]. It is not immediately clear how Sirt1 deficiency leads to persistence of cMet, or whether this receptor is in fact a direct target of Sirt1’s deacetylase activity.

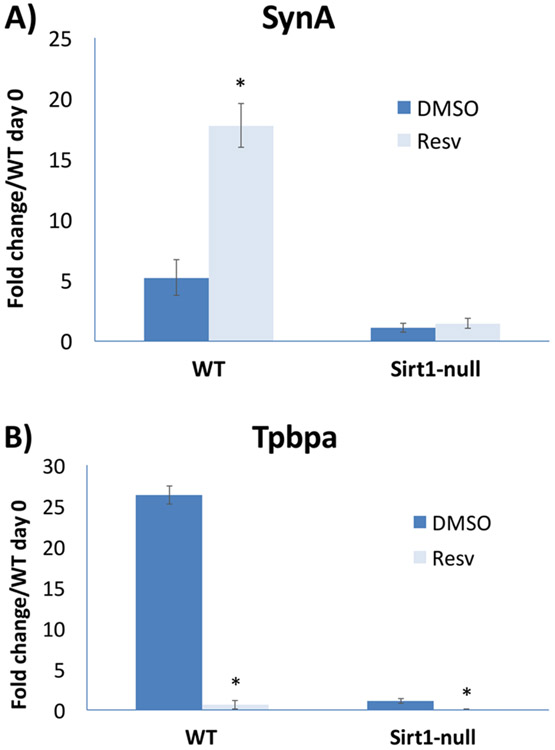

Notably, numerous other signaling pathways, some of which are known to be involved in TSC maintenance and differentiation, were also found to be altered in Sirt1-null TSC [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2017]. Among these were Smad- and Stat-dependent pathways, but also multiple metabolic pathways, including PPARγ. Interstingly, PPARγ RNA levels were reduced in differentiated Sirt1-null TSC, as confirmed by qPCR [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2018]; this was somewhat unexpected, as Sirt1 is best known as a negative regulator of PPARγ in adipose tissue. However, PPARγ downregulation can also partly explain the blunted differentiation phenotype of Sirt1-null TSC, at least with respect to labyrinthine differentiation. As with PPARγ, we also evaluated the effect of Sirt1 agonists on TSC differentiation. Treatment with resveratrol during differentiation led to a Sirt1-dependent induction of the labyrinthine marker SynA, though inhibition of the spongiotrophoblast marker Tpbpa appeared to be Sirt1-independent (Figure 2). This agonist-induced shift towards a trophoblast lineage involved in nutrient exchange is consistent with the role of Sirt1 as a nutrient sensor, and implies that Sirt1 may in fact serve a similar function in the placenta as in the embryo-proper.

Figure 2.

The effect of resveratrol treatment on mouse trophoblast differentiation. Mouse TSCs were differentiated, as previously described [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2018], in the presence of 25 μM resveratrol or DMSO carrier for a total of seven days. qPCR was performed for markers of labyrinthine trophoblast (SynA, A) or junctional zone (Tpbpa, B); values were normalized to 18S RNA and shown as fold change adjusted to the value of wild-type (WT) undifferentiated (day 0) cells. Note that resveratrol induces SynA in a Sirt1-dependent manner (A); however, inhibition of Tpbpa expression is Sirt1-independent, as the basal levels in Sirt1-null cells are further decreased by resveratrol treatment in these cells (B). A) * indicates P value of 0.0007. B) * indicates P value of 0.0001 for WT and 0.0057 for Sirt1-null cells.

Sirt1 is also expressed in human trophoblast; however, to date, no published studies have addressed the role of this deacetylase in maintenance/differentiation of trophoblast in the human placenta. Similarly, while numerous Sirt1 targets have been identified, affecting pathways as wide-ranging as transcription, metabolism, apoptosis, DNA damage repair, and autophagy [Simmons et al. 2015], direct targets of Sirt1 in trophoblast and placenta have yet to be explored in detail. Our own study, using microarray-based RNA profiling of WT and Sirt1-null TSCs, before and after differentiation, identified a series of altered genes and pathways, some of which were mentioned above [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2017], and some of which overlapped with pathways regulated by Sirt1 outside the placenta. However, a detailed proteomic profiling study, particularly one focused on changes in acetylation, is needed to identify potential direct targets of placental Sirt1.

Sirt1-PPARγ signaling in placental disease

Alterations in trophoblast differentiation and placental development are associated with numerous pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and gestational diabetes [Fisher, 2015; Kwak-Kim et al. 2014; Huynh et al. 2015]. These conditions are associated with a suboptimal maternal and placental micro-environment, exhibiting features of hypoxia, oxidative stress, inflammation, and/or hyperglycemia. Therefore, we will now attempt to summarize how these changes in micro-environment may affect PPARγ and/or Sirt1 signaling in the placenta. Since most studies regarding PPARγ and Sirt1 in trophoblast/placenta have focused on hypoxia, we will begin with this topic.

Hypoxia and PPARγ

Oxygen tension is an important variable in the placenta, both during normal development and in specific diseases of this organ [reviewed in Chang et al. 2017]. In conditions of low oxygen tension/hypoxia, numerous pathways are activated which subsequently affect tissue homeostasis. The best studied of these is that of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), a complex of two component proteins, the oxygen-stabilized HIF-α and the constitutively-expressed HIF-β subunits [Lee et al. 2004]. The HIF complex is required for placentation, and specifically for differentiation of trophoblast into the invasive lineage (trophoblast giant cells/TGCs in mouse, and extravillous trophoblast in human) [Adelman et al. 2000; Maltepe et al. 2005; Wakeland et al. 2017]. PPARγ was known to be affected by hypoxia through the HIF complex: specifically, adipocyte differentiation is inhibited by hypoxia, through a HIF-regulated transcriptional repressor’s effect on PPARγ2, the isoform specific to adipose tissue [Yun et al. 2002]. Based on this study, we evaluated the effect of hypoxia on PPARγ in mouse TSCs. We found that low oxygen tension inhibits PPARγ expression, but that this effect is independent of HIF [Tache et al. 2013]. In addition, forced expression of PPARγ under low oxygen tension partially restored labyrinthine trophoblast differentiation [Tache et al. 2013].

The above findings correlate with the hypoxia-associated placental pathology present in the maternal hypertensive disorder of preeclampsia (PE). Abnormal differentiation of syncytiotrophoblast, the lineage analogous to labyrinthine trophoblast in mice, is a hallmark of this disease, and is considered secondary to the reduced maternal blood flow to the placenta due to abnormal spiral artery remodeling by the invasive extravillous trophoblast cells [Fisher 2015]. In fact, PE placentas have reduced expression of PPARγ, as well as reduced levels of GCM1, a major regulator of labyrinthine/syncytiotrophoblast formation and a potential target of PPARγ, and its target the fusogenic protein, SYNCYTIN [He et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2004; Langbein et al. 2008]. These PE-like syncytiotrophoblast abnormalities have been recapitulated in vitro by downregulation of GCM1 in the floating human placental explant model [Baczyk et al. 2009]. We propose that this phenotype originates with downregulation of PPARγ under hypoxia, leading to reduced GCM1 and SYNCYTIN levels, which in turn adversely affect syncytiotrophoblast differentiation.

Another hallmark of PE is elevated circulating levels of the anti-angiogenic molecule soluble VEGF receptor-1, also known as soluble Flt-1 (sFlt-1) [Karumanchi and Epstein, 2007]. While the origin and etiology of elevated sFlt-1 secretion in PE placentas continue to be debated, several studies have shown a link between hypoxia and upregulation of sFlt-1 in human trophoblast [Nagamatsu et al. 2004; Li et al. 2005; Nevo et al. 2006; Munaut et al. 2008]. Our own study has shown a correlation between syncytiotrophoblast sFlt-1 levels and PE disease severity [Tache et al. 2011]. PPARγ activity has been linked to elevated levels of sFlt-1 in a rat model of PE: specifically, pregnant rats treated with a PPARγ antagonist exhibited PE-like symptoms such as elevated blood pressure, proteinuria, and reduced pup weight, and accompanied by increased plasma levels of sFlt-1 [McCarthy et al. 2011]. Interestingly, a separate study in mice linked reduced Gcm1 levels to elevated circulating levels of sFlt-1 [Bainbridge et al. 2012]. Together, these studies indicate that the PPARγ-Gcm1 axis may be involved in regulation of sFlt-1. We have also evaluated both sFlt-1 RNA levels and secretion in differentiated mouse TSC, following treatment with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (Figure 3). We noted reduced levels of sFlt-1 RNA and secretion following treatment with rosiglitazone; the latter did not affect sFlt-1 levels in WT-TSC subjected to hypoxia or in PPARγ-null TSC, under either normoxia or hypoxia, indicating that this effect was PPARγ-dependent (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The effect of rosiglitazone treatment on sFlt-1 in mouse trophoblast. Differentiated mouse TSCs, either wild-type (WT) or PPARγ-null, were treated with 1 μM rosiglitazone or DMSO carrier, either in normoxia (21% oxygen, N) or hypoxia (2% oxygen, H), then subjected to either qPCR (A) or ELISA (B) for sFlt-1. A) * indicates P value of 0.0005. B) * indicates P value of 0.0002.

Finally, PE is also characterized by increased levels of trophoblast apoptosis [Leung et al. 2001], a cellular process in which PPARγ is also involved. Interestingly, when term cytotrophoblast are cultured in hypoxia, differentiation into syncytiotrophoblast is blunted, and under severe hypoxia, apoptosis results [Nelson et al. 1999; Elchalal et al. 2004]. Treatment of these cells with the PPARγ agonist, troglitazone, under hypoxic conditions promoted differentiation and limited the apoptotic damage these cells experienced [Elchalal et al. 2004]. Together, the data provided here suggest that PPARγ should be considered as an important therapeutic target in placental diseases such as PE.

Hypoxia and Sirt1

Compared to the PPARγ story, the relationship between hypoxia and Sirt1 is more complex. However, several studies have identified Sirt1 as an upstream regulator of HIF-α subunits. Sirt1 can deacetylate HIF-1α, thus blocking recruitment of p300 and induction of HIF-regulated genes [Lim et al. 2010]; conversely, Sirt1 selectively stimulates HIF-2α activity, thus promoting signaling through this alternate HIF-α subunit during hypoxia [Dioum et al. 2009]. In turn, Sirt1 gene expression has been found to decrease in hypoxia, in a HIF-dependent manner, thus showing bi-directional signaling between these two pathways [Chen et al. 2011]. Expression of Sirt1 in trophoblast under hypoxic conditions has yet to be evaluated in detail. Our own studies using mouse TSC have not shown a consistent effect of hypoxia on Sirt1 expression (data not shown). However, one study, using human term primary trophoblast has shown induction of Sirt1 under hypoxia, leading to enhanced expression of the N-myc downregulated gene-1 (NDRG1) and reduced expression of p53, thus promoting cell survival [Chen et al. 2006]. Nevertheless, more detailed studies are required to determine the relationship between hypoxia, HIF, and Sirt1 in both trophoblast and placenta.

Similar to PPARγ, Sirt1 levels have recently been found to be reduced in syncytiotrophoblast of PE placentas by quantitative immunohistochemistry [Broady et al. 2017]. The authors hypothesize that, given Sirt1’s role in increasing longevity, this finding is likely associated with enhanced cellular senescence noted in PE [Broady et al. 2017]. Sirt1 activity has also been linked to PE in several studies. In one study, the Sirt1 agonist, resveratrol, was shown to attenuate sFlt-1 secretion, which was induced following treatment of normal human placental explants with either cytokines (including TNFα) or hypoxia (1% oxygen); resveratrol was also able to reduce sFlt-1 secretion from explants from PE placentas, albeit by only 25-30% [Cudmore et al. 2012]. In a more recent study, resveratrol was used to treat human primary term trophoblast, thereby reducing both secretion and mRNA levels of sFlt-1 [Hannan et al. 2017]. We recently used differentiated WT and Sirt1-null mouse TSC and showed that treatment with resveratrol did reduce sFlt-1 mRNA and secretion, in a Sirt1-dependent manner; unlike PPARγ, however, the absence of Sirt1 was associated with significantly lower basal levels of sFlt-1 (Figure 4). Since PPARγ levels are decreased in the absence of Sirt1 [Arul Nambi Rajan et al. 2017], there are likely one or more other targets through which Sirt1 mediates sFlt-1 basal levels. Finally, resveratrol was also able to reverse the elevated blood pressure and proteinuria in a rat model of PE, induced by treatment with NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) [Zou et al. 2014]. These data suggest that, while Sirt1 is required for induction of basal sFlt-1 expression, it may also serve a viable therapeutic target for PE, similar to PPARγ.

Figure 4.

The effect of resveratrol treatment on sFlt-1 in mouse trophoblast. Differentiated mouse TSCs, either wild-type (WT) or Sirt1-null, were treated with 25 μM resveratrol or DMSO carrier, then subjected to either qPCR (A) or ELISA (B) for sFlt-1. A) * indicates P value of 0.0185. B) * indicates P value of 0.0243.

Placental oxidative stress and the effects on PPARγ and Sirt1

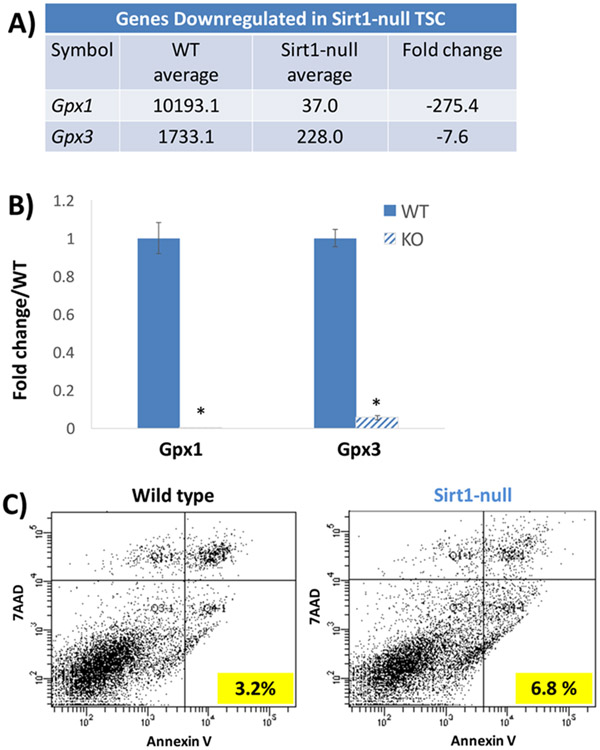

PE placentas have also been associated with oxidative stress [Burton et al. 2009], a condition of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can be secondary to hypoxia, ischemia/reoxygenation, or decreased levels of anti-oxidants. Since the effects of hypoxia were discussed above, we will focus here on oxidative stress induced by means other than hypoxia. In a rat model of maternal micronutrient deficiency, diets lacking either folic acid or vitamin B12 during pregnancy led to increased plasma markers of oxidative stress and lower levels of placental PPARγ mRNA; however, while the placenta weights were not affected, no fetal or maternal consequences were described [Meher et al. 2014]. With regard to Sirt1, oxidative stress, induced by hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase treatment of human placental explants, decreased Sirt1 mRNA and protein expression, and reduced expression of the glucose transporter gene, GLUT1, and subsequent glucose uptake [Lappas et al. 2012]. The latter phenotypes were abrogated by treatment with resveratrol [Lappas et al. 2012]. Similarly, resveratrol treatment reduced placental oxidative stress and apoptosis in the above-described rat model of L-NAME-induced PE [Zou et al. 2014]. In our study of mouse TSC, microarray-based RNA profiling identified the glutathione peroxidase genes, Gpx1 and Gpx3, in the top 10 genes downregulated in Sirt1-null TSCs (Figure 5a). The Gpx family of proteins helps protect cells against oxidative stress by catalyzing the reduction of organic hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide by glutathione [Matsubara et al. 2015]. Downregulation of Gpx1 and Gpx3 in Sirt1-null TSC, compared to WT-TSC, was confirmed by qPCR and was associated with a higher rate of apoptosis in the Sirt1-null cells (Figure 5b-c). Whether Sirt1-null TSCs are more susceptible to oxidative stress due to the significant reduction in Gpx enzymes remains to be further evaluated.

Figure 5.

Reduced expression of glutathione peroxidase genes and elevated apoptotic index in Sirt1-null mouse TSCs. A) Microarray profiling of wild-type (WT) or Sirt1-null TSCs revealed two glutathione peroxidase genes, Gpx1 and Gpx3, to be in the top 10 of genes downregulated in the absence of Sirt1. B) qPCR confirmed these findings. * indicates P=0.0002 for Gpx1 and P=0.0001 for Gpx3. C) Double-labeling of WT and Sirt1-null TSCs with 7-AAD and annexin V showed doubling of apoptotic index (percent of annexin V+/7AAD− cells).

Placental inflammation and the effects on PPARγ and Sirt1

Inflammation in the placenta can be either physiologic or pathologic. An example of the former is the increased inflammation noted in the placenta and fetal membranes in normal term labor [reviewed in Hadley et al. 2017]. This pro-inflammatory environment at labor has been associated with no change in PPARγ [Marvin et al. 2000], but a reduction in Sirt1 expression in both fetal membranes (chorion) as well as placental (chorionic villous) tissues [Lappas et al. 2011, Kim et al. 2013]. Human placental Sirt1 levels are sensitive to pro-inflammatory cytokines, and have been shown to decrease following treatment with TNF and IL1β [Lappas et al. 2011]. Intriguingly, visfatin/Nampt, an adipocytokine and Sirt1 activator, had a positive correlation with Sirt1 levels and was found to be elevated in placentas of obese women prior to term labor, suggesting a potential mechanism whereby the labor-associated decrease in Sirt1 is prevented, resulting in post-term delivery commonly observed in obese pregnant women [Tsai et al. 2015].

Pathologic inflammation in the placenta is associated with PE as well as maternal obesity [Harmon et al. 2016; Leon-Garcia et al. 2016]. Elevated levels of placental inflammation have been associated with reduced placental PPARγ mRNA expression, in the setting of micronutrient deficiency in pregnant rats [Meher et al. 2014]. Interestingly, in a mouse model of LPS-induced intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), pre-treatment of pregnant mice with the PPARγ agonist, rosiglitazone, reduced the rate of IUFD from 64% to 16% [Bo et al. 2016]. This effect was associated with increased nuclear localization of PPARγ in placental trophoblast, reductions in placental pro-inflammatory factors including IL-6 and TNFα, and blockage of LPS-evoked nuclear translocation of NF-κB in labyrinthine trophoblast [Bo et al. 2016]. Finally, in a rat model of LPS-induced PE, transplantation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) led to reduced pro-inflammatory markers, including IL-6 and TNFα, and higher levels of PPARγ, in the placenta; this was accompanied by lower blood pressure and higher fetal weight, compared to LPS treatment alone [Wang et al. 2016].

Less is known about the relationship between obesity-associated placental inflammation and Sirt1/PPARγ expression. This type of inflammation is characterized by infiltration of T cells and macrophages into chorionic villi, best described as a non-infectious chronic villitis/villitis of unknown etiology; in the setting of maternal obesity, this lesion is twice as common in placentas from female fetuses, a phenomenon that remains unexplained [Leon-Garcia et al. 2016]. While macrophage infiltration of adipose tissue has been associated with decreased Sirt1 expression [Gillum et al. 2011], we have not noted alterations in Sirt1 or PPARγ expression in placentas associated with maternal obesity (data not shown). However, in a study using a mouse model of high-fat feeding during pregnancy, we noted reduced Sirt1 and increased PPARγ expression in placentas [Qiao et al. 2015]. This was associated with elevated placental lipoprotein lipase (LPL) protein and activity, as well as increased fetal body fat content, suggesting that maternal overnutrition affects fetal development through alterations in the Sirt1-PPARγ axis [Qiao et al. 2015]. Whether this phenotype works through inflammatory mediators remains to be seen. We have noted a reduction in Sirt1 levels in WT mouse TSCs treated with IL-6 (data not shown); however, we have not yet evaluated how this is linked to other markers of trophoblast differentiation or function.

Hyperglycemia and placental PPARγ and Sirt1

Finally, while there have not been any studies on alterations of placental Sirt1 in the setting of maternal diabetes, studies on placental PPARγ levels in this setting have shown noteworthy results. PPARγ levels were increased both in human primary trophoblast exposed to hyperglycemic conditions [Cawyer et al. 2014], as well as in placentas from streptozotocin-induced diabetic pregnant mice [Suwaki et al. 2007]. At the same time, multiple studies have identified reduced placental PPARγ expression, in the setting of gestational diabetes [Jawerbaum et al. 2004; Holdsworth-Carson et al. 2010; Knabl et al. 2014; Capobianco et al. 2016], with one of these studies showing decreased levels of this protein in both syncytiotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast [Knabl et al. 2014]. Further studies are needed to more thoroughly evaluate the link between maternal diabetes and PPARγ levels in trophoblast and placenta, with consideration of both maternal glycemic control and associated fetal/neonatal growth outcomes.

Figure 6 summarizes the effects of various stressors on both PPARγ and Sirt1 levels in the placenta.

Figure 6.

Flow chart indicating relationship between placental PPARγ (A) or Sirt1 (B) and various stressors. (+) indicates induction and (−) indicates inhibition of expression/activity (“?” indicates insufficient data). *Note that while hyperglycemia has been shown to increase PPARγ levels, the latter appear to be decreased in the setting of gestational diabetes. See text for further details on this and other stressors affecting either protein.

Conclusions and future directions

While much remains to be evaluated regarding the function of both PPARγ and Sirt1, and particularly of the latter, in the placenta, the above studies indicate that both of these proteins play key roles, not just in the development of this important transient organ, but in the various pathologies associated with pregnancy complications. One of the major gaps in knowledge in this area is the role of these two proteins in placental nutrient sensing and the associated effect on fetal growth. While the absence of expression of each of these genes is associated with fetal growth restriction, their exact role(s) in placental nutrient sensing remain(s) to be explored. Furthermore, in such follow-up studies, the crosstalk between these two pathways must also be considered. For example, while PPARγ levels are significantly reduced in the absence of Sirt1 in mouse TSCs, Sirt1 appears to negatively regulate PPARγ in the placenta, in the setting of maternal high fat feeding, much like its function in white adipose tissue. While these results may be related to differences in the system being probed (single cell type in vitro vs. the intact tissue in vivo), future studies should evaluate changes in expression of one protein, even if the other protein is the sole target. This is most important in experiments with agonists: in this context, TSCs derived from embryos genetically deficient for one or the other protein are highly useful for testing off-target effects. In addition, evaluation of the functions of these proteins should ideally be done alongside accurate measurements of their endogenous activities; this will require development of more optimized activity assays which can be carried out both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, further identification and characterization of downstream targets of both placental PPARγ and Sirt1 are needed, including potential shared targets. Given the availability of drugs targeting these pathways, future studies have the potential to lead to development of therapeutics for multiple placenta-based pregnancy complications.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01-HD071100 (M.M.P.). P.L. was supported by a grant from the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2017A030313624).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Adelman DM, Gertsenstein M, Nagy A, Simon MC & Maltepe E 2000. Placental cell fates are regulated in vivo by HIF-mediated hypoxia responses. Genes and Development 14 3191–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arul Nambi Rajan K, Khater M, Soncin F, Pizzo D, Moretto-Zita M, Pham J, Stus O, Iyer P, Tache V, Laurent LC, et al. 2018. Sirtuin1 is required for proper trophoblast differentiation and placental development in mice. Placenta 62 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baczyk D, Drewlo S, Proctor L, Dunk C, Lye S, Kingdom J. 2009. Glial cell missing-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of the human trophoblast. Cell Death and Differentiation 16 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge SA, Minhas A, Whiteley KJ, Qu D, Sled JG, Kingdom JC, Adamson SL 2012. Effects of reduced Gcm1 expression on trophoblast morphology, fetoplacental vascularity, and pregnancy outcomes in mice. Hypertension 59 732–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM 1999. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Molecular Cell 4 585–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo QL, Chen YH, Yu Z, Fu L, Zhou Y, Zhang GB, Wang H, Zhang ZH, Xu DX 2016. Rosiglitazone pretreatment protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced fetal demise through inhibiting placental inflammation. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 423 51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broady AJ, Loichinger MH, Ahn HJ, Davy PM, Allsopp RC, Bryant-Greenwood GD 2017. Protective proteins and telomere length in placentas from patients with pre-eclampsia in the last trimester of gestation. Placenta 50 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton GJ, Jauniaux E 2015. What is the placenta? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 213 S6.e1, S6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC 2009. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta 30 473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleri E, Pochetti G, Dossou KSS, Laghezza A, Montanari R, Capelli D, Prada E, Loiodice F, Massolini G, Bernier M, et al. 2014. Resveratrol and its metabolites bind to PPARs. Chembiochem 15 1154–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capobianco E, Fornes D, Linenberg I, Powell TL, Jansson T, Jawerbaum A 2016. A novel rat model of gestational diabetes induced by intrauterine programming is associated with alterations in placental signaling and fetal overgrowth. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 422 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawyer CR, Horvat D, Leonard D, Allen SR, Jones RO, Zawieja DC, Kuehl TJ, Uddin MN 2014. Hyperglycemia impairs cytotrophoblast function via stress signaling. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 211 541.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CW, Wakeland AK, Parast MM 2018. Trophoblast lineage specification, differentiation and their regulation by oxygen tension. Journal of Endocrinology 236 R1–R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Chen CY, Yang YC, Su TH, Chen H 2004. Decreased placental GCM1 (glial cells missing) gene expression in pre-eclampsia. Placenta 25 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y 2006. N-myc down-regulated gene 1 modulates the response of term human trophoblasts to hypoxic injury. Journal of Biological Chemistry 281 2764–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Dioum EM, Hogg RT, Gerard RD, Garcia JÁ 2011. Hypoxia increases sirtuin 1 expression in a hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent manner. Journal of Biological Chemistry 286 13869–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis JP, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt FW, Chua KF 2003. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A 100 10794–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore MJ, Ramma W, Cai M, Fujisawa T, Ahmad S, Al-Ani B, Ahmed A 2012. Resveratrol inhibits the release of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1) from human placenta. American Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology 206 253.e10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dioum EM, Chen R, Alexander MS, Zhang Q, Hogg RT, Gerard RD, Garcia JA 2009. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha signaling by the stress-responsive deacetylase sirtuin 1. Science 324 1289–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Whitesall SE, D'Alecy LG, Duquaine DC, Brosius FC 3rd, Gonzalez FJ, Vinson C, Pierre MA, Milstone DS, et al. 2007. Hypotension, lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance in generalized PPARgamma-deficient mice rescued from embryonic lethality. Journal of Clinical Investigation 117 812–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elchalal U, Humphrey RG, Smith SD, Hu C, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM 2004. Troglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced injury in cultured term human trophoblasts. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 191 2154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farghali H, Kutinová Canová N, Lekić N 2013. Resveratrol and related compounds as antioxidants with an allosteric mechanism of action in epigenetic drug targets. Physiological Research 62 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SJ 2015. Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 213 S115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier T, Handschuh K, Tsatsaris V, Evain-Brion D 2007. Involvement of PPARgamma in human trophoblast invasion. Placenta 28 Suppl A S76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giblin W, Skinner ME, Lombard DB 2014. Sirtuins: guardians of mammalian healthspan. Trends in Genetics 30 271–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum MP, Kotas ME, Erion DM, Kursawe R, Chatterjee P, Nead KT, Muise ES, Hsiao JJ, Frederick DW, Yonemitsu S, et al. 2011. SirT1 regulates adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetes 60 3235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley EE, Richardson LS, Torloni MR, Menon R 2017. Gestational tissue inflammatory biomarkers at term labor: A systematic review of literature. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2017 doi: 10.1111/aji.12776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Zhou R, Niu J, McNutt MA, Wang P, Tong T 2010. SIRT1 is regulated by a PPAR{γ}-SIRT1 negative feedback loop associated with senescence. Nucleic Acids Research 38 7458–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschuh K, Guibourdenche J, Cocquebert M, Tsatsaris V, Vidaud M, Evain-Brion D, Fournier T 2009. Expression and regulation by PPARgamma of hCG alpha- and beta-subunits: comparison between villous and invasive extravillous trophoblastic cells. Placenta 30 1016–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan NJ, Brownfoot FC, Cannon P, Deo M, Beard S, Nguyen TV, Palmer KR, Tong S, Kaitu'u-Lino TJ 2017. Resveratrol inhibits release of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin and improves vascular dysfunction - implications as a preeclampsia treatment. Scientific Reports 7 1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon AC, Cornelius DC, Amaral LM, Faulkner JL, Cunningham MW Jr, Wallace K, LaMarca B 2016. The role of inflammation in the pathology of preeclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 130 409–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Chen Z, Sun Q, Li Y, Gu H, Ni X 2014. Reduced expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in preeclamptic placentas is associated with decreased PPARγ but increased PPARα expression. Endocrinology 155 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth-Carson SJ, Lim R, Mitton A, Whitehead C, Rice GE, Permezel M, Lappas M 2010. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are altered in pathologies of the human placenta: gestational diabetes mellitus, intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia. Placenta 31 222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh J, Dawson D, Roberts D, Bentley-Lewis R 2015. A systematic review of placental pathology in maternal diabetes mellitus. Placenta 36 101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JL, Carter AM, Chamley LW 2012. Human placentation from nidation to 5 weeks of gestation. Part I: What do we know about formative placental development following implantation? Placenta 33 327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawerbaum A, Capobianco E, Pustovrh C, White V, Baier M, Salzberg S, Pesaresi M, Gonzalez E 2004. Influence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation by its endogenous ligand 15-deoxy Delta12,14 prostaglandin J2 on nitric oxide production in term placental tissues from diabetic women. Molecular Human Reproduction 10 671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karumanchi SA, Epstein FH 2007. Placental ischemia and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1: cause or consequence of preeclampsia? Kidney International 71 959–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Shim SH, Sung SR, Lee KA, Shim JY, Cha DH, Lee KJ 2013. Gene expression analysis of the microdissected trophoblast layer of human placenta after the spontaneous onset of labor. PLoS One 8 e77648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knabl J, Hüttenbrenner R, Hutter S, Günthner-Biller M, Vrekoussis T, Karl K, Friese K, Kainer F, Jeschke U 2014. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) is down regulated in trophoblast cells of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and in trophoblast tumour cells BeWo in vitro after stimulation with PPARγ agonists. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 42 179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Milner J 2012. SIRT1, metabolism and cancer. Current Opinion in Oncology 24 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppen A, Kalkhoven E 2010. Brown vs white adipocytes: the PPARgamma coregulator story. FEBS Letters. 584 3250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Miki H, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Komeda K, Satoh S, Nakano R, Ishii C, Sugiyama T, et al. 1999. PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Molecular Cell 4 597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak-Kim J, Bao S, Lee SK, Kim JW, Gilman-Sachs A 2014. Immunological modes of pregnancy loss: inflammation, immune effectors, and stress. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 72 129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langbein M, Strick R, Strissel PL, Vogt N, Parsch H, Beckmann MW, Schild RL. 2008. Impaired cytotrophoblast cell-cell fusion is associated with reduced Syncytin and increased apoptosis in patients with placental dysfunction. Mol Reprod Dev 75: 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappas M, Mitton A, Lim R, Barker G, Riley C, Permezel M 2011. SIRT1 is a novel regulator of key pathways of human labor. Biology of Reproduction 84 167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Bae SH, Jeong JW, Kim SH & Kim KW 2004. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)alpha: its protein stability and biological functions. Experimental and Molecular Medicine 36 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Garcia SM, Roeder HA, Nelson KK, Liao X, Pizzo DP, Laurent LC, Parast MM, LaCoursiere DY 2016. Maternal obesity and sex-specific differences in placental pathology. Placenta 38 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DN, Smith SC, To KF, Sahota DS, Baker PN 2001. Increased placental apoptosis in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 184 1249–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levytska K, Drewlo S, Baczyk D, Kingdom J 2014. PPAR- γ Regulates Trophoblast Differentiation in the BeWo Cell Model. PPAR Research 2014 637251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Gu B, Zhang Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y 2005. Hypoxia-induced increase in soluble Flt-1 production correlates with enhanced oxidative stress in trophoblast cells from the human placenta. Placenta 26 210–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Lee YM, Chun YS, Chen J, Kim JE, Park JW 2010. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Molecular Cell 38 864–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltepe E, Krampitz GW, Okazaki KM, Red-Horse K, Mak W, Simon MC, Fisher SJ 2005. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent histone deacetylase activity determines stem cell fate in the placenta. Development 132 3393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin KW, Eykholt RL, Keelan JA, Sato TA, Mitchell MD 2000. The 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) receptor, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma) is expressed in human gestational tissues and is functionally active in JEG3 choriocarcinoma cells. Placenta 21: 436–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, Higaki T, Matsubara Y, Nawa A 2015. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16 4600–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurney MW, Yang X, Jardine K, Hixon M, Boekelheide K, Webb JR, Lansdorp PM, Lemieux M 2003. The mammalian SIR2alpha protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Biology 23 38–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meher AP, Joshi AA, Joshi SR 2014. Maternal micronutrients, omega-3 fatty acids, and placental PPARγ expression. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 39 793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munaut C, Lorquet S, Pequeux C, Blacher S, Berndt S, Frankenne F, Foidart JM 2008. Hypoxia is responsible for soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1) but not for soluble endoglin induction in villous trophoblast. Human Reproduction 23 1407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamatsu T, Fujii T, Kusumi M, Zou L, Yamashita T, Osuga Y, Momoeda M, Kozuma S, Taketani Y 2004. Cytotrophoblasts up-regulate soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 expression under reduced oxygen: an implication for the placental vascular development and the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Endocrinology 145 4838–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DM, Johnson RD, Smith SD, Anteby EY, Sadovsky Y 1999. Hypoxia limits differentiation and up-regulates expression and activity of prostaglandin H synthase 2 in cultured trophoblast from term human placenta. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 180 896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo O, Soleymanlou N, Wu Y, Xu J, Kingdom J, Many A, Zamudio S, Caniggia I 2006. Increased expression of sFlt-1 in in vivo and in vitro models of human placental hypoxia is mediated by HIF-1. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 291 R1085–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KW, Halperin DS, Tontonoz P 2008. Before they were fat: adipocyte progenitors. Cell Metabolism 8 454–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Kurtev M, Chung N, Topark-Ngarm A, Senawong T, Machado De Oliveira R, Leid M, McBurney MW, Guarente L 2004. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-gamma. Nature 429 771–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L, Wang L, Kon N, Zhao W, Lee S, Zhang Y, Rosenbaum M, Zhao Y, Gu W, Farmer SR, et al. 2012. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell 150 620–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L, Guo Z, Bosco C, Guidotti S, Wang Y, Wang M, Parast M, Schaack J, Hay WW Jr, Moore TR, et al. 2015. Maternal High-Fat Feeding Increases Placental Lipoprotein Lipase Activity by Reducing SIRT1 Expression in Mice. Diabetes 64 3111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaiff WT, Carlson MG, Smith SD, Levy R, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y 2000. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma modulates differentiation of human trophoblast in a ligand-specific manner. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 85 3874–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaiff WT, Knapp FF Jr, Barak Y, Biron-Shental T, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y 2007. Ligand-activated peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma alters placental morphology and placental fatty acid uptake in mice. Endocrinology 148 3625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalom-Barak T, Nicholas JM, Wang Y, Zhang X, Ong ES, Young TH, Gendler SJ, Evans RM, Barak Y 2004. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma controls Muc1 transcription in trophoblasts. Molecular and Cellular Biology 24 10661–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalom-Barak T, Zhang X, Chu T, Timothy Schaiff W, Reddy JK, Xu J, Sadovsky Y, Barak Y 2012. Placental PPARγ regulates spatiotemporally diverse genes and a unique metabolic network. Developmental Biology 372 143–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons GE, Pruitt WM, Pruitt K 2015. Diverse roles of Sirt1 in cancer biology and lipid metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16 950–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soncin F, Natale D, Parast MM 2015. Signaling pathways in mouse and human trophoblast differentiation: a comparative review. Cell and Molecular Life Sciences 72 1291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwaki N, Masuyama H, Masumoto A, Takamoto N, Hiramatsu Y 2007. Expression and potential role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in the placenta of diabetic pregnancy. Placenta 28 315–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taché V, Ciric A, Moretto-Zita M, Li Y, Peng J, Maltepe E, Milstone DS, Parast MM 2013. Hypoxia and trophoblast differentiation: a key role for PPARγ. Stem Cells and Development 22 2815–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taché V, LaCoursiere DY, Saleemuddin A, Parast MM 2011. Placental expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1/soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 correlates with severity of clinical preeclampsia and villous hypermaturity. Human Pathology 42 1283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornburg KL, Marshall N 2015. The placenta is the center of the chronic disease universe. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 213 S14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai PJ, Davis J, Thompson K, Bryant-Greenwood G 2015. Visfatin/Nampt and SIRT1: Roles in Postterm Delivery in Pregnancies Associated With Obesity. Reproductive Sciences 22 1028–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M, Lee LK, Chhabra A, Kim YJ, Sasidharan R, Van Handel B, Wang Y, Kamata M, Kamran P, Sereti KI, et al. 2013. c-Met-dependent multipotent labyrinth trophoblast progenitors establish placental exchange interface. Developmental Cell 27 373–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeland AK, Soncin F, Moretto-Zita M, Chang CW, Horii M, Pizzo D, Nelson KK, Laurent LC, Parast MM 2017. Hypoxia Directs Human Extravillous Trophoblast Differentiation in a Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Dependent Manner. American Journal of Pathology 187 767–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Yu Y, Guan HB, Qiao C 2016. Effect of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in a Rat Model of Preeclampsia. Reproductive Sciences 23 1058–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RH, Sengupta K, Li C, Kim HS, Cao L, Xiao C, Kim S, Xu X, Zheng Y, Chilton B, et al. 2008. Impaired DNA damage response, genome instability, and tumorigenesis in SIRT1 mutant mice. Cancer Cell 14 312–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Kulp SK, Chen Ching-Shih 2010. Energy restriction as an antitumor target of thiazolidinediones. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 9780–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun Z, Maecker HL, Johnson RS, Giaccia AJ 2002. Inhibition of PPAR gamma 2 gene expression by the HIF-1-regulated gene DEC1/Stra13: a mechanism for regulation of adipogenesis by hypoxia. Developmental Cell 2 331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Zuo Q, Huang S, Yu X, Jiang Z, Zou S, Fan M, Sun L 2014. Resveratrol inhibits trophoblast apoptosis through oxidative stress in preeclampsia-model rats. Molecules 19 20570–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]