Abstract

The alternative polyadenylation of the mRNA encoding the amyloid precursor protein (APP) involved in Alzheimer's disease generates two molecules, with the first of these containing 258 additional nucleotides in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). We have previously shown that these 258 nucleotides increase the translation of APP mRNA injected in Xenopus oocytes (5). Here, we demonstrate that this mechanism occurs in CHO cells as well. We also present evidence that the 3′UTR containing 8 nucleotides more than the short 3′UTR allows the recovery of an efficiency of translation similar to that of the long 3′UTR. Moreover, the two guanine residues located at the 3′ ends of these 8 nucleotides play a key role in the translational control. Using gel retardation mobility shift assay, we show that proteins from Xenopus oocytes, CHO cells, and human brain specifically bind to the short 3′UTR but not to the long one. The two guanine residues involved in the translational control inhibit this specific binding by 65%. These results indicate that there is a correlation between the binding of proteins to the 3′UTR of APP mRNA and the efficiency of mRNA translation, and that a GG motif controls both binding of proteins and translation.

The control of gene expression governs cell differentiation. The first step of this control is provided by the transcription of specific genes. In eucaryotic cells, the scanning of a gene by the RNA polymerase II leads to the production of a nuclear transcript which, in most cases, will undergo three major modifications: capping of its 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), polyadenylation of the 3′UTR, and splicing of introns (13, 38).

At the postranscriptional level, the efficiency of translation of mature mRNA can also regulate gene expression. The phosphorylation of initiation factors of translation, which interact with the 5′ end of mRNAs, has been demonstrated to modulate translation (21, 31).

The presence of secondary structures in the 5′UTR can also influence mRNA translation either by increasing the binding affinity of some eucaryotic initiation factors (18) or by interacting with cellular proteins which can completely inhibit the initiation of translation (9, 33).

Although the 3′UTR is located downstream of the coding sequence, it has been widely demonstrated that this region can also modulate mRNA translation (41). The poly(A) tail is one element of the 3′UTR implicated in both the stability of mRNA and the regulation of its translation (34). The poly(A) tail can increase the stability of an mRNA molecule by protecting the mRNA from digestion by 3′→5′ exonucleases (7). A more dynamic role has been attributed to the poly(A) tail since it was demonstrated that its removal from the 3′ end of capped mRNA decreases translation (22, 37). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae the enhancement of translation mediated by the poly(A) tail requires the formation of a complex between the poly(A) tail and a poly(A) binding protein (PABP) since the depletion of the PABP results in the inhibition of translation (36). This complex is supposed to promote the initiation of translation of capped mRNA by promoting the recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit (40). In addition, the PABP was also demonstrated to interact with eukaryotic initiation factors (11, 17). The interaction of PABP with different components of the preinitiation complex of translation might explain why a sequence located downstream of a coding region is able to control translation.

Adenosine-uridine rich (AUR) sequences within the 3′UTR are known to affect mRNA translation (3, 43, 44). In this case, the mechanism involved in the regulation of translation is not clearly understood. Indeed, AUR sequences have been demonstrated to reduce the stability of mRNA (16), but in some cases AUR sequences inhibit translation without affecting the mRNA stability (15). Proteins can interact with AUR sequences (2, 19, 24, 42), and some of these protein-AUR complexes can either increase mRNA stability (27) or decrease their translational efficiency (10, 46).

In erythroblasts, inhibitory proteins have been purified and demonstrated to interact with oligonucleotide repeats present in the 3′UTR of the lipoxygenase mRNA (25).

We have previously shown that alternative polyadenylation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) mRNA generates two sets of transcripts which differ by the length of their 3′UTR and by their translational efficiency (5). The 258 nucleotides (nt) located within the two utilized polyadenylation sites are clearly involved in the modulation of translation. In this study, we demonstrate that the addition of only 8 nt to the short mRNA allows the recovery of an efficiency of translation similar to that of the long mRNA.

Since recent data show that protein-3′UTR complexes are involved in the regulation of translation (14, 25, 29, 39), we have also investigated a possible interaction between proteins and the 3′UTR of the APP mRNA. We demonstrate that proteins specifically bind to the 3′UTR of the short APP mRNA. The same proteins do not interact with the long 3′UTR. The addition of 8 nucleotides to the short 3′UTR inhibits the specific binding of proteins and induces a concomitant increase of translational efficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions.

The sequence from the 3′UTR of the APP695 cDNA was amplified from the pHMG695 plasmid (4) with a sense oligonucleotide (5′GTGCACACATTAGGCATTGAGAC3′) and an antisense oligonucleotide (5′GGATCCGGATCCGCTCCTCCAAGAATGTATT TATTTAC3′). A PstI-BamHI fragment of this PCR product was cloned in the PstI-BamHI sites of either the pSP64CAT plasmid (5) or the pSP64 plasmid to obtain pSP64CAT APP and pSP64 APP, respectively.

Cell culture.

CHO cells were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2 in Ham's F-12 medium with l-glutamine (Biowhitaker) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biowhitaker), penicillin, and streptomycin.

In vitro transcription and production of 32P-labeled probes.

Four micrograms of pSP64CAT APP or pSP64 APP plasmids was linearized with BamHI, XmaI, or SmaI. They were then transcribed with 40 U of SP6 RNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim) in 60 μl of reaction buffer containing 149 U of RNase inhibitor (HPRI; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and a 1 mM concentration of each nucleotide triphosphate. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C prior to the addition of 15 U of RNase-free DNase (GIBCO-BRL). A further incubation of 20 min at 37°C allowed the digestion of the DNA template. The transcripts were then filtered on Sephadex G-50 columns, phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and lyophilized. The mRNA was resuspended in deionized water and analyzed on agarose gels. For transcripts used in in vivo translation experiments, 7-methyl guanosine (Boehringer Mannheim) was added to the mixture and the concentration of GTP was reduced to 167 μM. Radiolabeled probes were transcribed from 1 μg of linearized DNA in the presence of 100 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 72 μM unlabeled UTP, and an 800 μM concentration of each of the remaining three unlabeled nucleotide triphosphates. The approximate concentration of the labeled probes was calculated according to the specific activity of [α-32P]UTP, the percentage of UTP molecules in each transcript, and the percentage of [α-32P]UTP incorporation in the synthesized probe.

Addition of a poly(A) tail was performed in vitro using poly(A) polymerase (Pharmacia Biotech). Briefly, 1 μg of mRNA was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 50 μl of Tris buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM MnCl2, 250 mM NaCl, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per μl) containing 250 μM of ATP and 2 U of poly(A) polymerase. The transcripts were ethanol precipitated and further sequenced to determine the length of the poly(A) tail.

The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) antisense riboprobe used in the Northern blot analyses was synthesized in the presence of T7 RNA polymerase from the pGEM CAT linearized with PstI.

In vivo translation of capped mRNA.

For translation in Xenopus oocytes, the capped mRNAs were diluted in deionized water to a final concentration of 100 ng/μl. They were then injected in stage VI Xenopus oocytes (50 nl of mRNA solution/oocyte) in which they were translated at room temperature for 6 h. During the in vivo translation, the oocytes were incubated in Marc's modified Ringer's solution. The oocytes were then immersed in liquid nitrogen to stop the translation process. Translation in CHO cells was performed by transfection of 106 cells with 2 μg of capped mRNA using the Lipofectamine reagent from Gibco. After 4 h incubation, the cells were scrapped, harvested by centrifugation at 200 × g, and stored at −80°C.

CAT assay.

Xenopus oocytes were crushed in a 250 mM Tris solution (50 μl/oocyte) and CHO cells were lysed in the same solution by three freezing-thawing steps. The amount of CAT protein produced after translation was evaluated by the CAT assay described by Gorman et al. (8). The quantification of the CAT assay was performed using a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

RNA isolation.

The injected oocytes were crushed in 500 μl of a Tris solution (10 mM, pH 7.4) containing NaCl (150 mM), EDTA (1 mM), and 100 μg of proteinase K. Following phenol-chloroform extraction, total RNA was ethanol precipitated and resuspend in water.

Total RNA from CHO cells was extracted from the pellet using the Tripure reagent from Boehringer Mannheim.

Northern blot analysis.

Ten micrograms of total RNA was denatured in a solution containing dimethyl sulfoxide, glyoxal, and 10 mM phosphate buffer; loaded on 1% agarose gel, and transferred after migration on nylon membrane Hybond-N (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The membrane was hybridized for 16 h at 65°C with the CAT antisense riboprobe in 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–50% formamide–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution, then washed twice for 30 min at 68°C in 2× SSC–1.5% SDS solution and twice for 30 min at 72°C in 0.2× SSC–1% SDS solution.

The 18S and 28S rRNAs were revealed using methylene blue staining (20).

Preparation of cellular and tissular extracts.

Stage VI oocytes, CHO cells, or brain tissues were homogenized on ice with a Potter homogenizer in 2 volumes of Tris buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5) containing glycerol (25%), KCl (50 mM), EDTA (0.1 mM), and dithiothreitol (0.5 mM) in the presence of protease inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [1 mM], leupeptin (1 μg/ml) and pepstatin (0.1 μg/ml). The sample was centrifuged at 4°C for 1 h at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was recovered and aliquoted at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit.

Mobility shift assay.

Radiolabeled 3′UTR-L (344 nt), 3′ UTR-2G (88 nt), and 3′ UTR-S (86 nt) were transcribed in vitro from the pSP64 APP plasmid restricted by BamHI, XmaI, and SmaI, respectively. [α-32P]UTP-labeled 3′UTR mRNA (2.2 fmol) was incubated on ice in 16 μl of a solution containing either 10 μg of proteins or water (control), 20 μg of yeast tRNA, 149 U of HPRI and 8 μl of reaction buffer (Tris [20 mM, pH 7.4], MnCl2 [0.5 mM], KCl [100 mM], CaCl2 [20 mM], ZnCl2 [0.5 mM], dithiothreitol [1 mM], glycerol [5%]). For competition experiments, a 50× molar excess of unlabeled 3′UTR mRNA was added to the reaction mixture prior to the addition of labeled probe. After 20 min of incubation, 20 U of RNase T1 was added to the sample, which was further incubated for 45 min at 37°C. Sample was then loaded on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel prepared in TBE buffer (Tris [89 mM], boric acid [89 mM], EDTA [2 mM, pH 8]) and electrophoresed at a constant current (30 mA) for 3 to 4 h. The gel was then dried and subjected to autoradiography on X-Omat film (Kodak).

RESULTS

The 3′UTR of APP mRNA regulates translation in the absence of a poly(A) tail.

We have previously shown that the APP mRNA uses two polyadenylation sites separated by 258 nt. In Xenopus oocytes, the APP mRNA with the long 3′UTR (APP-L) was translated three times more efficiently than the APP mRNA with the short 3′UTR (APP-S). When the 3′UTR of the APP mRNA [2871 to poly(A) tail in Fig. 1] was cloned downstream of the CAT cDNA sequence, the in vivo translation of these polyadenylated chimeric mRNAs in Xenopus oocytes indicated that the long mRNA produced two times more protein than the short one (5). Since the poly(A) tail was demonstrated to be able to influence translation (22), we first measured whether the difference in translation was confirmed after removal of the poly(A) sequence from the long and the short chimeric mRNAs.

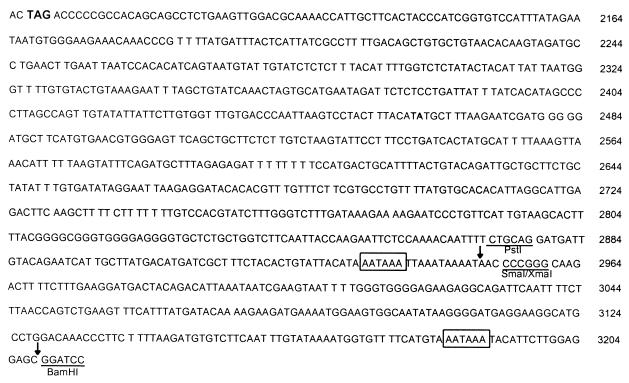

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the 3′UTR of APP mRNA. The PstI-BamHI fragment involved in the translational control was amplified by PCR and cloned downstream of a CAT reporter gene. Boxes indicate the two polyadenylation sites used by the APP mRNA. Restriction sites used for linearization or cloning are underlined. Arrows indicate the position of the poly(A) tail on the short or the long 3′UTR. The translation termination codon is indicated in boldface type. The sequence is numbered according to the numbering of Kang et al. (12).

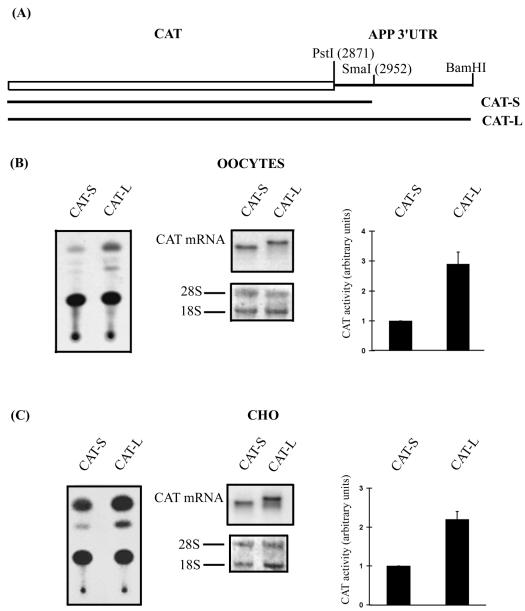

A PstI-BamHI PCR fragment amplified from the long 3′UTR of APP mRNA (Fig. 1) was cloned in the pSP64CAT vector (Fig. 2A). In vitro transcription performed after linearization with BamHI generated the long chimeric CAT mRNA bearing the 3′UTR-L of APP mRNA (CAT-L), which is not polyadenylated. When the same construct was linearized with SmaI (Fig. 2A), in vitro transcription allowed us to produce a short chimeric CAT mRNA bearing the 3′UTR-S of APP mRNA (CAT-S), which is not polyadenylated. The 3′UTR of this last messenger contains 6 nt more than the short 3′UTR previously described (5) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

(A) The pSP64CAT APP plasmid results from the cloning of the PstI-BamHI PCR fragment of the 3′UTR of APP mRNA downstream of the CAT reporter gene. This construct was digested with SmaI or BamHI to produce CAT-S and CAT-L mRNAs after in vitro transcription. These mRNAs were translated in Xenopus oocytes (B) as well as in CHO cells (C). Typical CAT assays were performed with extracts from both cellular models. Northern blot analysis was performed with a CAT antisense riboprobe, and the rRNAs were visualized by methylene blue staining of the membranes. Phosphorimager quantification of several CAT assays indicates that in Xenopus oocytes (B) or in CHO cells (C), CAT-L mRNA produces 2.9 ± 0.4 (n = 5) and 2.2 ± 0.2 (n = 4) times more CAT activity than CAT-S mRNA, respectively. Results are expressed as means + standard deviations (error bars).

CAT-S and CAT-L mRNAs were injected in Xenopus oocytes, and the CAT activity was measured 6 h later as previously described (5). The results in Fig. 2B shows that more CAT activity was measured from CAT-L than from CAT-S mRNA although Northern blot analysis showed that similar amounts of both mRNAs were recovered from injected oocytes. Quantification of several CAT assays indicated that CAT-L produces 2.9 ± 0.4 (mean ± standard deviation) (n = 5) times more CAT activity than CAT-S.

A 1.9-fold difference was previously measured with constructs containing a poly(A) sequence (Table 1). We conclude, therefore, that the difference of in vivo translation between the long and the short mRNAs is still observed when mRNAs are not polyadenylated.

TABLE 1.

Regulation of translation by the 3′UTR of the APP mRNAa

| Cell type | Poly(A) status of APP 3′UTR | CAT-L/CAT-S | CAT-2G/CAT-S | APP-L/APP-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenopus oocyte | − | 2.9 ± 0.4 (n = 5) | 2.7 ± 0.3 (n = 3) | |

| + | 1.9 ± 0.3 (n = 3) | 3 | ||

| CHO | − | 2.2 ± 0.2 (n = 4) | 3.1 ± 0.6 (n = 3) | |

| + | 3.3 ± 0.3 (n = 3) | 4.5 |

The long or short 3′UTR of APP mRNA or the short 3′UTR with two additional G residues of APP mRNA was cloned downstream the CAT or the APP coding sequence. These mRNAs containing (+) or not containing (−) a poly(A) sequence were translated in Xenopus oocytes or in CHO cells. The efficiency of translation is expressed as the ratio of the quantified proteins produced by each of the translated mRNA.

It has been demonstrated that the enhancement of translation mediated by the poly(A) tail needs the presence of a PABP which can interact with eucaryotic initiation factors (17), thus facilitating the reinitiation of translation. The PABP expression is developmentally regulated in Xenopus oocytes, and its mRNA is translated from the blastula stage (47). Since all the in vivo translations were performed in stage VI oocytes, the absence of PABP at this stage could explain why the polyadenylation of mRNAs is dispensable for the control of mRNA translation in oocytes. Consequently, the influence of the polyA tail on the regulation of translation was studied in CHO cells.

CHO cells were transfected with the cDNA encoding either APP-S or APP-L. The APP protein was quantified and normalized for APP mRNA. Results presented in Table 1 show that the APP-L mRNA produces 4.5 times more APP when compared to the APP-S mRNA.

CHO cells were transfected with cDNA encoding either the CAT-L or CAT-S chimeric mRNAs (5). At 48 h after transfection, the CAT activity produced by translation of the in situ polyadenylated mRNAs was quantified and normalized for the CAT mRNA. CAT-L mRNA was demonstrated to produce 3.3 ± 0.3 (n = 3) times more CAT activity than CAT-S mRNA (Table 1).

The nonpolyadenylated chimeric CAT-L and CAT-S mRNAs injected in Xenopus oocytes were also transfected in CHO cells. The results presented in Fig. 2C indicate that more CAT activity was measured from CAT-L mRNA. After Northern blot analysis, CAT-L mRNA was more abundant in CHO cells than CAT-S mRNA. However, quantification of several CAT assays normalized for CAT mRNA indicates that CAT-L mRNA produces 2.2 ± 0.2 (n = 4) times more CAT activity than CAT-S mRNA (Fig. 2C and Table 1).

Altogether, these results clearly indicate that, in both Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells, the 3′UTR of APP mRNA regulates translation without polyadenylation of the long and the short mRNAs. Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that elongation of the short 3′UTR sequence with a poly(A) tail or a sequence which is not related to APP mRNA does not allow recovery of the efficiency of translation of the long 3′UTR sequence (5). This demonstrates that the nucleotide sequence rather than the length of the sequence that follows the short 3′UTR is critical for the control of translation.

Identification of the nucleotide sequence of the 3′UTR of APP mRNA involved in the regulation of translation.

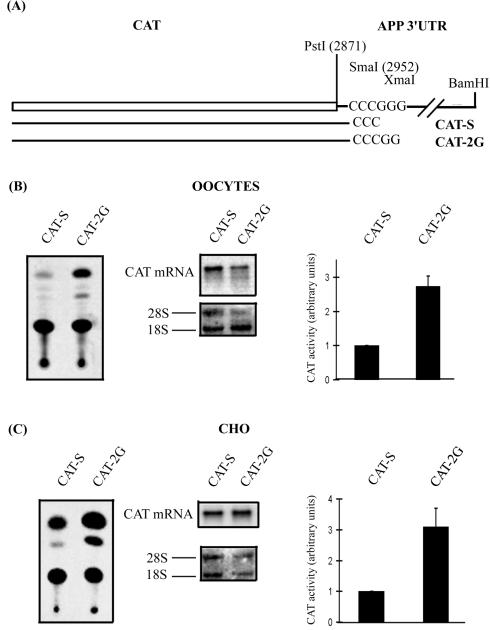

Since the 3′UTR of APP mRNA by itself regulates translation, we have tried to localize the nucleotide sequence responsible for this regulation. Therefore, elongation of the short 3′UTR was performed and the possible influence on translation was monitored. Linearization of the CAT-APP 3′UTR construct with SmaI allowed us to add 6 nt to the short 3′UTR (Fig. 1). In vivo translation of the CAT-S and CAT-L mRNA demonstrates that these additional nucleotides failed to restore the efficiency of translation (Fig. 2). The CAT-APP 3′UTR construct was then linearized by XmaI. The XmaI site is located in the 3′UTR of the APP mRNA at position 2958 (Fig. 1). This allowed us to produce the CAT-2G mRNA, which differs from the CAT-S mRNA by only two additional G residues at the 3′ end (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) The pSP64CAT APP plasmid was linearized with SmaI or XmaI to produce CAT-S and CAT-2G mRNAs. These mRNAs were translated in Xenopus oocytes (B) as well as in CHO cells (C). Typical CAT assays were performed with extracts from both cellular models. Northern blot analysis was performed with a CAT antisense riboprobe, and the rRNAs were visualized by methylene blue staining of the membranes. Phosphorimager quantification of several CAT assays indicates that in Xenopus oocytes (B) or in CHO cells (C), CAT-2G mRNA produces 2.7 ± 0.3 (n = 3) and 3.1 ± 0.6 (n = 3) times more CAT activity than CAT-S mRNA, respectively. Results are expressed as means + standard deviations.

After 6 h of in vivo translation in Xenopus oocytes, the CAT-2G mRNA produced more CAT activity than the CAT-S mRNA (Fig. 3B). Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3B) showed, however, that this is not related to the recovery of a larger amount of CAT-2G mRNA from injected oocytes. Quantification of several CAT assays indicated that CAT-2G mRNA produces 2.73 ± 0.3 (n = 3) times more CAT activity than CAT-S mRNA (Fig. 3B).

In vitro transcribed CAT-2G and CAT-S mRNA were also transfected in CHO cells. The CAT activity was quantified and normalized for CAT mRNA. CAT-2G mRNA produces 3.1 ± 0.6 (n = 3) more CAT activity than CAT-S mRNA (Fig. 3C).

Altogether, these results demonstrate that elongation of the short 3′UTR by the next 3′ 8 nt increases translation to the level observed with the long 3′UTR. This translational control is particularly dependent on the presence of the two G residues localized at the 3′ end of this 8 nt sequence.

Interaction between the 3′UTR of APP mRNA and proteins.

Since interactions between proteins and the 3′UTR of mRNAs are involved in the regulation of translation (24), it was of interest to determine whether proteins from Xenopus oocytes or CHO cells could bind to the 3′UTR of APP mRNA.

The PstI-BamHI fragment of the long 3′UTR of APP mRNA (Fig. 1) was cloned in the pSP64 plasmid. After linearization with BamHI, SmaI, and XmaI, the mRNA corresponding to the long 3′UTR (3′UTR-L), the short 3′UTR (3′UTR-S), and the short 3′UTR elongated with two guanine residues (3′UTR-2G) were generated by in vitro transcription and used in electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

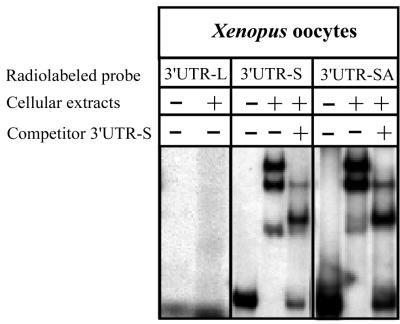

When incubated in the presence of a protein extract from Xenopus oocytes, radiolabeled 3′UTR-L failed to interact with proteins (Fig. 4 and 5A). On the contrary, 3′UTR-S mRNA interacts with proteins, and different RNA-protein complexes are formed (Fig. 4 and 5A). Some of these complexes appeared to result from a specific interaction, since a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled short 3′UTR mRNA completely abolished the formation of these RNA-protein complexes (Fig. 4 and 5A). Addition of an 80-residue poly(A) tail to 3′UTR-S does not inhibit the interaction of this short sequence with the same proteins (Fig. 4). This indicates that the nucleotide sequence rather than the length of 3′UTR-L is critical for the binding of proteins.

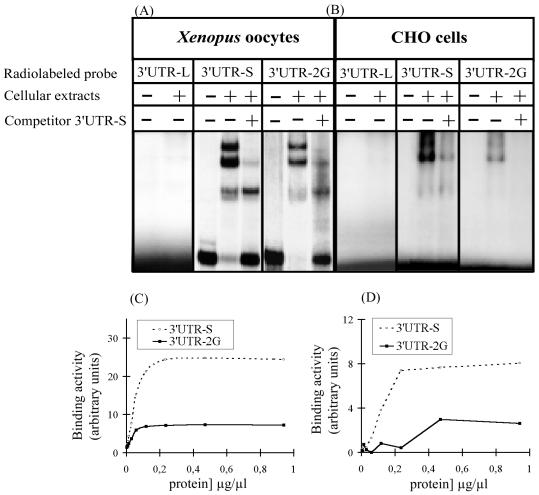

FIG. 4.

The PstI-BamHI PCR fragment of the 3′UTR from APP mRNA (Fig. 1) was cloned downstream of the SP6 promoter of the pSP64 plasmid. This plasmid was digested with BamHI or SmaI. The linearized plasmids were in vitro transcribed to produce 3′UTR-L and 3′UTR-S. These probes were tested for their ability to bind proteins from Xenopus oocyte. The longer radiolabeled 3′UTR (3′UTR-L) failed to interact with proteins from Xenopus oocytes, while the shorter radiolabeled 3′UTR (3′UTR-S) was able to form specific complexes, as demonstrated by competition with a 50-fold excess of the same cold probe. Addition of an 80-residue poly(A) tail to the radiolabeled 3′UTR-S (3′UTR-SA) does not interfere with the binding of these proteins.

FIG. 5.

The PstI-BamHI PCR fragment of the 3′UTR from APP mRNA (Fig. 1) was cloned downstream of the SP6 promoter of the pSP64 plasmid. This plasmid was digested with BamHI, SmaI, or XmaI. The linearized plasmids were in vitro transcribed to produce 3′UTR-L, 3′UTR-S, and 3′UTR-2G, respectively. These probes were tested for their ability to bind proteins from Xenopus oocytes (A) or from CHO cells (B). The longer radiolabeled 3′UTR (3′UTR-L) failed to interact with proteins from Xenopus oocytes or CHO extracts, while the shorter radiolabeled 3′UTR (3′UTR-S) was able to form specific complexes, as demonstrated by competition with a 50-fold excess of the same cold probe. 3′UTR-2G and 3′UTR-S bind the same proteins, since it is possible to displace complexes on radiolabeled 3′UTR-2G with a 50-fold excess of cold 3′UTR-S. However, when radiolabeled 3′UTR-S and 3′UTR-2G probes with similar specific activity were incubated with increasing concentrations of proteins, more 3′UTR-S was engaged in the formation of complexes (C and D).

When incubated with the same cellular extracts from Xenopus oocytes, 3′UTR-2G mRNA forms mRNA-protein complexes (Fig. 5A), with a pattern identical to that observed with the 3′UTR-S mRNA (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled 3′UTR-S mRNA was able to prevent the formation of the same specific complexes (Fig. 5A), indicating that the same proteins bind to both 3′UTR-S and 3′UTR-2G mRNAs. However, the amount of 3′UTR-2G mRNA found in complexes is much lower as compared to the 3′UTR-S mRNA. To further analyze this difference, the same amount of either 3′UTR-S or 3′UTR-2G mRNA at the same specific radioactivity was incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of proteins from Xenopus oocytes, and the radioactivity associated with the complexes was quantified. The saturation curves shown in Fig. 5C indicate that the addition of two guanine residues to 3′UTR-S decreased by 70% the amount of complexes formed.

When incubated with CHO cell extracts, the 3′UTR-L probe failed to interact with proteins (Fig. 5B). On the contrary, 3′UTR-S mRNA formed specific complexes with proteins from CHO cells (Fig. 5B). The 3′UTR-2G mRNA interacts with the same proteins as 3′UTR-S, since a 50× molar excess of unlabeled 3′UTR-S mRNA prevents the formation of the complexes with the radiolabeled 3′UTR-2G mRNA (Fig. 5B). However, the addition of two guanine residues to the 3′UTR-S mRNA decreases by 62% the amount of complexes formed (Fig. 5D).

Interestingly enough, in both Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells, this higher capacity of 3′UTR-S to form complexes is linked to a lower translation efficiency of the CAT-S mRNA compared to that of CAT-2G mRNA. Furthermore, proteins which interact with 3′UTR-S do not form complexes with 3′UTR-L, which drives a better translation of a coding sequence. Therefore, a possible function of these proteins as inhibitors of translation cannot be excluded.

3′UTR-S forms complexes with proteins from human brain extracts.

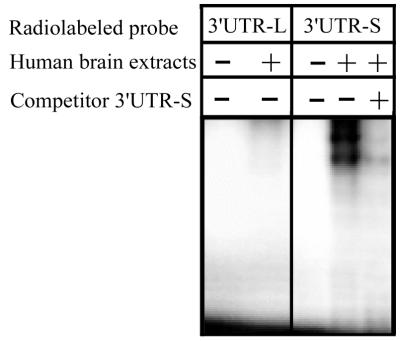

In both Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells, mRNAs bearing the 3′UTR-L are better translated than those bearing the 3′UTR-S. This difference in translation efficiency correlates with the specific binding of proteins to 3′UTR-S. To investigate whether such 3′UTR-protein interactions could occur in the human brain, radiolabeled 3′UTR-S and 3′UTR-L mRNA were incubated in the presence of a human brain extract. Interestingly enough, radiolabeled 3′UTR-L mRNA failed to form complexes, while the 3′UTR-S mRNA specifically interacted with human brain proteins (Fig. 6). Therefore, these results suggest that the translational control by the 3′UTR of APP mRNA could occur in the human brain as well.

FIG. 6.

Interaction of the 3′UTR of APP mRNA with proteins from human brain. When incubated with human brain extracts, 3′UTR-L failed to interact with proteins. On the contrary, 3′UTR-S shows specific interaction.

DISCUSSION

Alternative polyadenylation, a mechanism used by numerous genes (6), results in the production of mRNA molecules differing in the length of their 3′-terminal exon. These mRNAs generally encode the same protein, and the alternative polyadenylation could appear to be of low importance in cellular function. Nevertheless, recent data have demonstrated that the preferential use of a polyadenylation site could be associated with a modification of either the stability of the mRNA or the efficiency of its translation (5, 23, 30).

The mRNA encoding the APP involved in Alzheimer's disease uses two polyadenylation sites. This generates a long and a short mRNA, the former containing 258 additional nt in the 3′UTR. We have previously shown that, compared to the short polyadenylated 3′UTR, the long polyadenylated 3′UTR enhances the translation of APP mRNA (5). We wondered whether the full-length 258 nt sequence could enhance translation without the presence of a poly(A) tail. We also investigated the region of this 258-nt sequence which was implicated in the regulation of translation. Finally, we have studied the possible role of interactions between proteins and the 3′UTR of APP mRNA in the modulation of translation.

The 3′UTR of APP mRNA by itself modulates translation, without the presence of a poly(A) tail.

Nonpolyadenylated chimeric CAT mRNAs, either CAT-L or CAT-S, were injected in Xenopus oocytes or transfected in CHO cells. In these two cellular models, the CAT-L mRNA was translated more efficiently than the CAT-S mRNA (Fig. 2D; Table 1). These results clearly indicate that the 3′UTR of APP mRNA by itself regulates translation in Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells, even without the polyadenylation of the long and the short mRNAs.

Addition of 8 nt 3′ to the APP-S mRNA results in an enhanced efficiency of translation.

To study the sequence of the 3′UTR involved in the modulation of translation of the APP mRNA (5), 8 nt of the long 3′UTR of APP mRNA was added to the APP-S mRNA. We demonstrate that the addition of these 8 nt is sufficient to abolish the relative inhibition of the short mRNA translation (Fig. 3). This regulation occurs in both Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells. Interestingly, the two guanine residues of the 3′ end of this 8-nt sequence play a key role in the regulation of translation.

Binding of proteins to the short 3′UTR of APP mRNA correlates with a decreased efficiency of translation.

Numerous cases have been reported in which the translational control is mediated by protein-RNA interaction. Since the long 3′UTR of APP mRNA increases its translation, we wondered whether this could result from the binding of an activator of translation to this sequence.

Surprisingly, our data show that the long 3′UTR failed to interact with proteins from Xenopus oocytes, CHO cells, and human brain homogenate. On the contrary, the short 3′UTR specifically interacts with proteins. Addition of the two guanine residues 3′ to the 3′UTR-S results in a 65 to 70% decrease of the amount of RNA-protein complexes formed. This difference related to the presence of 2 additional nt could result from the alteration of a stable structure needed for the formation of the complexes. In CHO cells as well as in Xenopus oocytes, the lack of complexes (3′UTR-L) or a decrease of the amount of the mRNA found in complexes (3′UTR-2G) correlates with an increased efficiency of translation. On the contrary, an efficient and specific binding of 3′UTR-S to proteins correlates with a decreased efficiency of translation. Therefore, proteins involved in the formation of these complexes could be involved in the translational control of the APP mRNA.

Although the nucleotide sequence involved in the specific APP mRNA-protein interactions is present in both the short and the long 3′UTR, the specific complexes are only found with the short 3′UTR. The absence of these specific interactions between proteins and the long 3′UTR could result from the presence of secondary structures in the long nucleotide sequence.

The nucleotide sequence rather than the length of the sequence following the short 3′UTR of APP mRNA seems of importance to prevent the formation of complexes. Indeed, addition of 80 A residues to this short 3′UTR by poly(A) polymerase has no effect on the binding of the proteins to the short sequence.

Different translational controls of APP mRNA have been recently reported. In the 5′UTR, APP mRNA contains a sequence homologous to the iron-responsive element which modulates translation in response to interleukin 1 stimulation of astrocytoma cells (32). In the 3′UTR, a 29-oligonucleotide element (28, 45) and an 81-oligonucleotide element (1) have been demonstrated to increase the stability of the APP mRNA through protein-mRNA interactions. These stabilizing elements are located upstream of the regulatory sequence reported here and have no homology with our cis sequence.

These different posttranscriptional controls of APP mRNA translation and stability could be of importance, since the overproduction of APP could be related to the development of the characteristic neuropathological lesions of Alzheimer's disease (35). Such an overproduction of APP has been well documented in Down's syndrome patients and is related to the trisomy of the chromosome 21, which carries the APP gene. In these patients, abundant senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are found in adult brain. In patients with Alzheimer's disease, the number of APP genes is the same as that in normal subjects (26), but the control of translation and stability of the APP mRNA could modify APP production without additional copy of the APP gene. The further identification of proteins which could inhibit APP mRNA translation by interacting with its 3′UTR will be useful in controlling the production of APP, which is transformed into amyloid peptide, the major constituent of the amyloid core of senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Véronique Kruys for gifts of pGEM CAT and the pSP64 plasmid. We also acknowledge Bernadette Tasiaux, Huguette Delhez, and Jacques Doumont for their technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Belgian Queen Elizabeth Medical Fundation. J.-N.O. is a senior research associate of the Belgian FNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amara F M, Junaid A, Clough R R, Liang B. TGF-beta(1), regulation of Alzheimer' amyloid precursor protein mRNA expression in a normal human astrocyte cell line: mRNA stabilization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;71:42–49. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brewer G. An A+U-rich element RNA-binding factor regulates c-myc mRNA stability in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2460–2466. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C-Y A, Shyu A-B. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czech C, Delaere P, Macq A-F, Reibaud M, Dreisler S, Touchet N, Schombert B, Mazadier M, Mercken L, Theisen M, Pradier L, Octave J N, Beyreuther K, Tremp G. Proteolytical processing of mutated human amyloid precursor protein in transgenic mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:108–116. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Sauvage F, Kruys V, Marinx O, Huez G, Octave J N. Alternative polyadenylation of the amyloid protein precursor mRNA regulates translation. EMBO J. 1992;11:3099–3103. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards-Gilbert G, Veraldi K L, Milcareck C. Alternative poly(A) site selection in complex transcription units: means to an end? Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2547–2561. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford L P, Bagga P S, Wilusz J. The poly(A) tail inhibits the assembly of a 3′-to-5′ exonuclease in an vitro RNA stability system. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:398–406. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray N K, Wickens M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:399–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gueydan C, Houzet L, Marchant A, Sels A, Huez G, Kruys V. Engagement of tumor necrosis factor mRNA by an endotoxin-inducible cytoplasmic protein. Mol Med. 1996;2:479–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hentze M H. eIF4G: A multiple purpose ribosome adapter? Science. 1997;275:500–501. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang J, Lemaire H G, Unterbeck A, Salbaum M J, Masters C L, Grzeschik K H, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;331:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller W. No end yet to messenger RNA 3′ processing! Cell. 1995;81:829–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kern P A, Ranganathan G, Yukht A, Ong J M, Davis R C. Translational regulation of lipoprotein lipase by thryoid hormone is via a cytoplasmic repressor that interacts with the 3′ untranslated region. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:2332–2340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruys V, Wathelet M, Poupart P, Contreras R, Fiers W, Content J, Huez G. The untranslated region of the human interferon-β mRNA has an inhibitory effect on translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6030–6034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai, W. S., E. Carballo, J. R. Strum, E. A. Kennington, R. S. Phillips, and P. J. Blackshear. 1999. Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich element and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. 19:4311–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Le H, Tanguay R L, Balasta M L, Wei C-C, Browning K S, Metz A M, Goss D J, Gallie D R. Translation initiation factors eIF-iso4G and eIF-4B interact with the poly(A)-binding protein and increase its RNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16247–16255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liarakos C D, Theus S A, Watson A S, Wahba A J, Dholakia J N. The translation efficiency of ovalbumine mRNA is determined in part by a 5′-end hairpin structure. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;315:54–59. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malter J S. Identification of an AUUUA-specific messenger RNA binding protein. Science. 1989;246:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.2814487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrick W C. Mechanism and regulation of eucaryotic protein synthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:291–315. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.2.291-315.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munroe D, Jacobson A. mRNA poly(A) tail, a 3′ enhancer of translation initiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3441–3455. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myamoto S, Chiorini J A, Urcelay E, Safer B. Regulation of gene expression for translation initiation factor eIF-2a: importance of the 3′ untranslated region. Biochem J. 1996;315:791–798. doi: 10.1042/bj3150791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamaki T, Imamura J, Brewer G, Tsuruoka N, Koeffler H P. Characterization of adenosine-uridine-rich RNA binding factors. J Cell Physiol. 1995;65:484–492. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostareck D H, Ostareck-Ledere A, Wilm M, Thiele B J, Mann M, Hentze M W. mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: hnRNP K and hnRNP E1 regulate 15-lipoxygenase translation from the 3′ end. Cell. 1997;89:597–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podlisny M B, Lee G, Selkoe D J. Gene dosage of the amyloid beta precursor protein in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 1987;238:669–671. doi: 10.1126/science.2960019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajagopalan L E, Malter J S. Regulation of eukaryotic messenger RNA turnover. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1997;56:257–286. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajagopalan L E, Westmark C J, Jarzembowski J A, Malter J S. hnRNP C increases amyloid protein (APP) production by stabilizing APP mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3418–3423. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.14.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranganathan G, Ong J M, Yukht A, Saghizadeh M, Simsolo R B, Pauers A, Kern P A. Tissue specific expression of human lipoprotein lipase, effect of the 3′-untranslated region on translation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7149–7155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranganathan G, Vu D, Kern A. Translational regulation of lipoprotein lipase by epinephrine involves a trans-acting binding protein interacting with the 3′ untranslated region. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2515–2519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhoads R E. Regulation of eukaryotic protein synthesis by initiation factors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3017–3020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers J T, Leiter L M, McPhee J, Cahill C M, Zhan S S, Potter H, Nilsson L N. Translation of the alzheimer amyloid precursor protein mRNA is up-regulated by interleukin-1 through 5′-untranslated region sequences. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6421–6431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romeo D S, Park K, Roberts A B, Sporn M B, Kim S-J. Growth factor-b1 5′ untranslated region represses translation and specifically binds a cytosolic factor. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:759–766. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.6.8361501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross J. mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:423–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.423-450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rumble B, Retallack R, Hilbich C, Simms G, Multhaup G, Martins R, Hockey A, Montgomery P, Beyreuther K, Masters C L. Amyloid A4 protein and its precursor in Down's syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1446–1452. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906013202203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sachs A B, Davis R W. The poly(A) binding protein is required for poly(A) shortening and 60S ribosomal subunit-dependent translation initiation. Cell. 1989;58:857–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachs A B, Sarnow P, Hentze M W. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharp P A. Split genes and RNA splicing. Cell. 1994;77:805–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smibert C A, Wilson J E, Kerr K, Macdonald P M. Smaug protein represses translation of unlocalized nanos mRNA in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2600–2609. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarun S Z, Sachs A. A common function for mRNA 5′ and 3′ ends in translation initiation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomson A M, Rogers J T, Leedman P J. Iron regulatory proteins, iron responsive elements and ferritin mRNA translation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:1139–1152. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vakalopoulou E, Schaack J, Shenk T. A 32-kilodalton protein binds to AU-rich domains in the 3′ untranslated regions of rapidly degraded mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3355–3364. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winstall E, Gamache M, Raymond V. Rapid mRNA degradation mediated by the c-fos 3′ AU-rich element and that mediated by the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor 3′ AU-rich element occur through similar polysome-associated mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3796–3804. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu N, Chen C-Y, Shyu A-B. Modulation of the fate of cytoplasmic mRNA by AU-rich elements: key sequence features controlling mRNA deadenylation and decay. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4611–4621. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaidi S H E, Malter J S. Nucleolin and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C proteins specifically interact with the 3′-untranslated region of amyloid protein precursor mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17292–17298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zelus B D, Giebelhaus D H, Eib D W, Kenner K A, Moon R T. Expression of the poly(A)-binding protein during development of Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2756–2760. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao C, Tan W, Sokolowski M, Schwartz S. Identification of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins that interact specifically with an AU-rich, cis-acting inhibitory sequence in the 3′ untranslated region of human papillomavirus type 1 late mRNAs. J Virol. 1996;70:3659–3667. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3659-3667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]