Abstract

Background:

Engaging stakeholders in research carries the promise of enhancing the research relevance, transparency, and speed of getting findings into practice. By describing the context and functional aspects of stakeholder groups, like those working as community advisory boards (CABs), others can learn from these experiences and operationalize their own CABs. Our objective is to describe our experiences with diverse CABs affiliated with our community engagement group within our institution’s Clinical Translational Sciences Award (CTSA). We identify key contextual elements that are important to administering CABs.

Methods:

A group of investigators, staff, and community members engaged in a 6-month collaboration to describe their experiences of working with six research CABs. We identified the key contextual domains that illustrate how CABS are developed and sustained. Two lead authors, with experience with CABs and identifying contextual domains in other work, led a team of 13 through the process. Additionally, we devised a list of key tips to consider when devising CABs.

Results:

The final domains include (1) aligned missions among stakeholders (2) resources/support, (3) defined operational processes/shared power, (4) well-described member roles, and (5) understanding and mitigating challenges. The tips are a set of actions that support the domains.

Conclusions:

Identifying key contextual domains was relatively easy, despite differences in the respective CAB’s condition of focus, overall mission, or patient demographics represented. By contextualizing these five domains, other research and community partners can take an informed approach to move forward with CAB planning and engaged research.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, community advisory groups, translational research, stakeholder engagement, community engagement

Stakeholders representing patients, community members, industry partners, public health, payers, and others are increasingly engaging with research teams. Engaging stakeholders carries the promise of enhancing the relevance of research questions, increasing the transparency of the research process, and accelerating implementation of findings into practice.1,2 The hope is that such engagement helps to realign health care research with the needs of those most impacted by research initiatives.2

A critical organization catalyzing stakeholder inclusion in research is the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute has institutionalized an expectation that stakeholders guide the research process3 and multiple other federal and private funding agencies have strengthened their focus on engaging stakeholders in a similar manner. Consequently, research organizations interested in working with stakeholders need to explore and define processes that can optimally include stakeholders as active members on specific research projects and in the research enterprise more broadly.

Our CTSA leadership, staff, and affiliated community members at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill have worked to enhance stakeholder engagement in several ways, with an emphasis on developing and engaging CABs. CAB participants are community members who represent diverse populations that work directly with research teams to facilitate community input by providing feedback and advice on all aspects of the research process and provide a voice to the concerns and interests of their respective communities.4,5 CABs also help community members to better understand the risks and benefits of participating in research.4,6

The Community Academic Resources for Engaged Scholarship (CARES) group leads this work at UNC Chapel Hill and continues to develop expertise in engagement by being directly involved in CABs7-9 and by providing consultation to research groups about working with CABs.

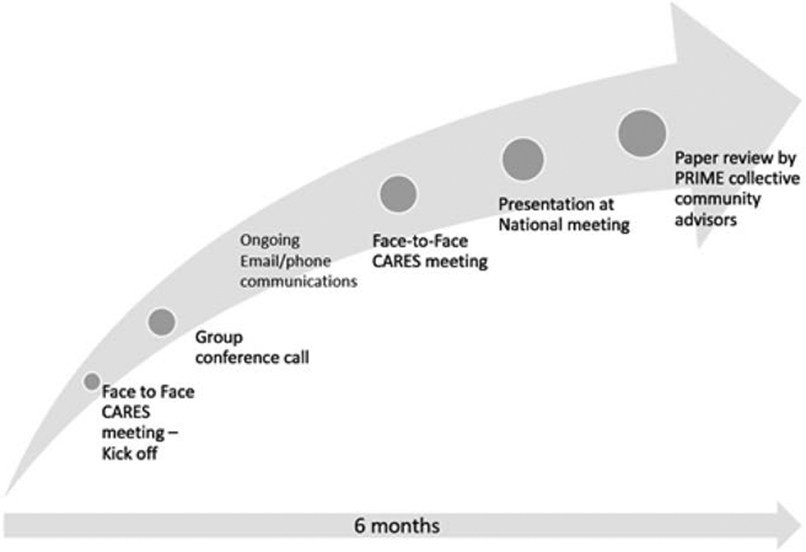

One noted gap in the stakeholder engagement literature is the relative paucity of details describing how engagement processes have been supported and implemented.10 To add to this literature, our CARES group engaged in a 6-month-long collaboration to share our CAB stories and identify important cross cutting contextual issues critical to support and sustain CABs (Figure 1). In this paper, we describe six unique case studies of CABs developed to guide individual research projects or support engaged research more broadly.

Figure 1.

Timeline of major activities to define key contextual domains.

OBJECTIVES

Our objective is to describe the details of our experiences in developing and implementing CABs that have guided translational research efforts at our institution. By sharing case examples and our summative thoughts on our identified contextual domains, we hope that other academic and community stakeholders may consider these domains, tips, and other aspects of this work when developing and implementing their own CABs.

METHODS

We solicited interest from CARES investigators and staff who had direct involvement in the past 4 years with CABs that were created to support a research mission. After this, we asked the group to briefly describe CAB experiences and assigned a lead contributor for each of seven identified CAB stories. Teams then worked independently to elaborate on CAB descriptions using an initial set of six contextual domains that were identified as starting points during our first meeting. Of note, although some of these initially identified domains mirrored those included in the work set forth by Tomoaia-Cotisel et al.11 others arose naturally as CAB stories were shared. Teams were asked to consider new or altered domains as they revised their drafts and reflected on their experiences.

The overall lead author (J.R.H.) reviewed the drafts and communicated with individual authors and team members by phone and email to clarify issues. The revised seven CAB descriptions were assembled and shared with all authors in preparation for a full group hour-long conference call that was held at the end of month two. During this call, we had group discussions to build further consensus on the naming, definitions. and number of key domains. The writing teams were then asked to revise their CAB descriptions using the updated domains. Again, individual communications were used to understand how well this revised structure worked for each team and CAB experience. At this point, one CARES team member who had been deeply involved in two of the CABs recommended removing one, because their two CAB stories had the same disease focus, involved many of the same people, and represented the same area of the state. Additionally, the one removed was not primarily focused on research. Thus, we agreed to include the six diverse CABs where research was a key aligning activity. The final list of six CABs included four research project CABS and two CABs that support research infrastructure and early phase project development.

Via further group communications by email, we merged two of the eight domains that were deemed similar and dropped one domain all together. Thus, we agreed on five final key contextual domains. These included the (1) collective motivation to work on a project, issue or health condition (aligned missions; thus, how missions were aligned or at least partially shared among the research and community members), (2) resources required (i.e., funds, meeting space, administrative support, other venues for communication outside of face to face meetings), (3) operations and decision making processes (i.e., how decisions were made, power shared, CAB members selected), (4) roles and activities of the respective CAB members, and (5) challenges, solutions and outcomes of the CAB experiences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Contextual Domains

| Domain | Definitions and Examples |

|---|---|

| Motivators and aligning missionsa | Funding environment, political environment, ongoing initiatives, and shared interests. |

| Resources | Funding, in kind or via direct dollars meeting space, administrative support, and training and capacity building. |

| Operations/decision making | Appointing CAB members and leaders, balancing power among research and community members, establishing decision making processes, defining meeting frequency, and devising methods of communicating. |

| Roles/activities | Specific activities in which CAB members were expected to participate beyond operational tasks. |

| Challenges, solutions, and outcomes | Key challenges faced by CABs and solutions or changes made to deal with challenges/barriers. |

CAB, community advisory board.

Of note, we did not include “motivators” of the research groups in the table due to space. As primarily translational researchers and staff, we are motivated to engage in research on particular diseases or issues and to include stakeholders in our work as part of a strong history of participatory research and community engagement at UNC Chapel Hill.

We reviewed our revised draft at another face-to-face CARES meeting and obtained additional feedback from CARES investigators and staff members who had not yet been involved in the CABs or writing process. We asked for general feedback and ideas on how to use this work to guide others in developing CABs. It was suggested that we (1) use a table format to describe four of the key contextual domains by CAB (Table 2), (2) separately describe the fifth domain (challenges/solutions/ outcomes) as text in the results section, (3) create a diagram to demonstrate our workflow and how it connects to “products” (Figure 2), and (4) include a list of “tips” for those interested in creating CABs (Table 3). Three CARES team members who were not previously involved in writing teams (D.R., T.B., C.B.) worked together to create the “tips” list. We then invited four of our community members who have guided our community-engaged processes since the inception of our first CTSA award in 2008 to review the paper and to provide critical feedback. This group is now organized as a Limited Liability Company named “Partnership in Research Integration, Mentoring and Education” (the PRIME collective). All four of these members had been involved in the development and implementation of at least one of our CABs described herein and, thus, had firsthand knowledge of the experiences. They provided overwhelmingly positive feedback and did not request substantive changes in the results, conclusions, tips, or other sections, and agreed that the manuscript would be useful to them in their own consultation work with researchers and community members.

Table 2.

Key Contextual Domains by CABa – Domains 1–4

| Motivators and Aligned Missionsb |

Resourcesc | Operations and decision making | Roles and Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| The “Health for Everyone in North Carolina” (He-NC) CAB: Patient and Clinician Groups Supporting Patients in their Journeys to Become Tobacco Free | |||

|

Practice network level: (1) Engaging with health care system for population health initiatives; (2) PCMH requirements Funding agency level: “What really works” to reduce cancer burden aim Patient level: (1) provide input on their lived experiences, especially the stigma of being a tobacco user; (2) influence the development of smoking cessation resources |

The He-NC/University Cancer Research Fund (2 years of funding) Gift certificates for CAB members ($50/h) Meeting space provided in kind by a local fitness center and the practice network |

Meeting schedule: face to face only Year 1 (site 1): six on-site “lunch and learns” with practice staff/clinicians Year 2 (sites 1, 2, 3): (1) one on-site, 1.5-hour meeting/site with patients who smoke and their support persons; 10–18 participants per site; (2) total 33 patient voices; (3) three separate 1.5-hour feedback sessions to individual practice teams; (4) one 2-hour Capstone meeting with practice staff and patients from 3 practices (14 member CAB) Decision making: voting with colored dots to represent importance of proposed activities or future research |

CAB level: discussions of what approaches and resources are needed to best support people who smoke in their quests to quit and best location (community or clinic) Practices network level: testing clinic level activities and problem solve implementation barriers |

| Parents and Teens Advising on Asthma Messaging | |||

| CAB member parents: “public health minded” CAB member teens: Degree to which asthma effected daily/school life Desire for a more normal life and personal control over their clinical care Ability to add more activities to their school resumes |

PCORI funded Grant supported compensation to teens (4 hours per month) and parents (8 hours per month) |

CAB members attended monthly project team meetings or conference calls (1 hour in length) Equitable and anonymous voting among all team members |

Review transcripts of focus groups to identify key themes to include in educational videos for teens Participate in de-identified voting processes to choose ultimate themes to include Attended study group meetings, helped problem solve, read drafts of manuscripts and participated as authors |

| The Monitor Trial Stakeholder Group -Patients, Providers, Public Health, Advocacy groups, Industry and Researchers with Diabetes Interests | |||

| Personal or professional diabetes interests Desire to address the uncertainty regarding benefits of glucose monitoring, especially given the associated costs Interests in new technologies that could improve communication of clinical data between patients and clinicians |

PCORI funded Grant-supported CAB member meeting compensation Industry partner provided in-kind time for incorporation of data into the EHR University supported training for research staff in accessing EHR data and communicating with providers |

One face-to-face, 2-hour kick off meeting; quarterly conference calls (agendas set 1 month before call) Decisions primarily made by verbal consensus Written feedback provided on abstracts and manuscripts |

Pre-award: input on specific aims, recruitment, intervention methods and project outcomes Post award: (1) review of materials; (2) participate in a PCORI-hosted webinar and other dissemination activities; (3) respond to “CAB experience and satisfaction” surveys; guided content and phrasing for messages generated from individual blood glucose results; (4) maintained engagement of practices experiencing high staff turnover Future work: review study results and discuss dissemination plans |

| Project Education and Access to Services and Testing (Project EAST) | |||

| Existence of community advocates that aimed to reduce disparities in HIV and AIDS prevalence and outcomes Desire to have relevant and targeted screening and treatment recommendations for diverse populations |

Multiple resources supporting at different time intervals including support from the UNC CTSA and modest support from the UNC Center for AIDS Research, Career award | Initial quarterly regional face-to-face meetings (1–2 hours), replaced by quarterly conference calls (1 hour) and a quarterly newsletter Investigator facilitated all meetings Community outreach specialists ensured attendance at the meetings CAB members had equal decision-making power with the research team |

Community leader: chose the CAB members CAB members: (1) defined the community, determined meeting frequency, ensured local relevance and acceptability of the developed intervention; (2) tested the intervention methods and materials and worked to preserve confidentiality of research subjects and CAB members due to stigma of HIV/AIDS in this region; (3) disseminated the messages and products of the work |

| The North Carolina Network Consortium (NCNC) Practice-based Research Advisory Board (RAB) | |||

|

RAB members: (1) previous experience with research in practice based environments; (2) interest in developing pragmatic trial infrastructure that leverage informatics resources; (3) include service on their resumes and CVs; (4) appreciated low touch engagement opportunity to bridge clinical work and research NCNC investigators: statewide experience in implementing practice based studies relevant to clinicians |

The UNC CTSA has provided in-kind and direct financial support to support NCNC conferences RAB member compensation can come from investigator funds, grant funds, or by applying for a CTSA supported “voucher” NCNC team members help guide survey design for RAB members to respond |

All communications via email Yearly email to all RAB members There is no formal decision making process; most decisions about RAB member engagement are made by NCNC investigators |

Consider responding to no more than three 10- to 15-item surveys per year Individual RAB members can suggest other clinicians to include in surveys Review annual email listening all current NCNC projects and provide email feedback |

| UNC CTSA CABs: CABs representing diverse stakeholders from 2 regions of North Carolina | |||

| UNC CTSA Program’s focus on enhancing of community engagement in all aspects of the research process History of multiple statewide efforts to include stakeholder voices |

UNC CTSA administrative support to help develop CAB policy and operational documents | Regional 2-hour quarterly dinner meetings An elected CAB member lead meetings Decisions made by consensus |

CAB members elected board members Provided input on organizational structure of the CAB and CAB meetings Reviewed, discussed, and advised investigators on research proposals |

CAB, community advisory board; CTSA, Clinical Translational Sciences Award; EHR, electronic health record; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCORI, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; PCMH, patient-centered medical home; RAB, research advisory board; UNC, University of North Carolina.

The fifth domain, challenges and solutions/outcomes, is included as text.

Includes motivators from stakeholders who collaborated with university-based researchers (community members, health care providers, industry partners, public health practitioners, others), not the motivators of the research teams.

CTSA funds have supported each of these CAB in various ways, such as by providing space, funds for food, modest staff support for both project specific and research infrastructure supporting CABs, informatics/data analysts time and via providing administrative support (especially for CAB 6) and in some cases (CAB 6) direct compensation ($50/h) for CAB member meetings.

Figure 2.

Contextual domains and impact of work.

Table 3.

Tips for Supporting Work with CABs

| Align missions |

|---|

| Find out early how CAB participation can benefit the CAB members, what are the other missions that can be aligned that motivate all parties to engage? |

| Review the goals and mission of the project at each meeting to reaffirm objectives. |

| Establish expectations |

| Begin with face-to-face meetings to build trust, co-identify project goals and methods of communication and decision making. |

| Allow time to let stakeholders and investigators understand the mission, their roles. |

| Add virtual meetings and conference calls to supplement face-to-face meetings. |

| Do not underestimate the ease of phone communications. Consider getting a toll-free number or free cell phone minutes for calls. |

| Consider co-leadership or alternate leadership at meetings between an investigator and key stakeholder. |

| Work out financial compensation details |

| Discuss with members what amount and method of reimbursement is appropriate. |

| Consider establishing a small grant/voucher program. |

| Consider gift cards or other means of compensating participants. |

| Engage early with groups within your organization/institutions to problem solve any institution specific requirements. |

| Resolve barriers around how to compensate specific populations such as those under the age of 18, undocumented immigrants, those with criminal backgrounds, or others. |

| Ensure lack of transportation is not a barrier to participation. |

| Plan for adequate time to enhance culture change |

| Establish CAB in the pre-award period if possible to allow for enough time for culture change such that work can commence in earnest when needed. |

| Multiple meetings may be needed to learn to share decision making power and define roles. |

| Participants should be flexible and willing to include other stakeholders not initially involved. Think of CAB as an evolving entity rather than static one and understand that often the original CAB members may be replaced overtime due to the dynamic nature of engaged work. |

| Consider including confidential methods to obtain feedback from CAB members to understand if they indeed feel valued, authentically engaged and have equal power with other members of the research team. |

| Find a respected leader who reiterates the importance of authentic and equitable stakeholder engagement and shared decision-making power. |

| Intellectual property issues |

| Meet with institutional legal advisors early in the process. |

| Include community stakeholders in intellectual property issues. |

| Discuss interpretation of data, authorship dissemination plans upfront. |

CAB, community advisory board.

RESULTS

Six cases studies are described using both text and table format. We share a brief overview of each case, detail the respective case’s content in each of the first four contextual domains in Table 2, and describe the fifth domain—common challenges, solutions, and outcomes—in aggregate in the text. We used a table format to allow for comparisons across the cases and for brevity. However, our CARES group felt that bulleted lists were not sufficient to describe some of the challenges and solutions (the fifth domain) that may be of particular interest to those trying to bridge the work of community and academic stakeholders. Thus, the fifth domain is described in the text.

CAB Overviews

CAB 1: The “Health for Everyone in North Carolina” CAB: Patient and Clinician Groups Supporting Patients in their Journeys to Become Tobacco Free.

Seven groups of patient stakeholders representing three different primary care practices in Central North Carolina engaged in a project to add the voice of the patient to the development, implementation, and maintenance of a pragmatic approach to caring for tobacco users in ambulatory primary care settings. The 14-member CAB, representing patients, clinical staff, a commercial payer, administrative personnel, implementation scientists, practice-based researchers, and tobacco treatment specialists participated in a final capstone meeting that ultimately served multiple purposes. Beyond intervention development, the CAB (1) served as the practice network’s first patient advisory board (a requirement for Patient Centered Medical Home recognition), (2) helped to select tools and educational video content to include in a subsequently funded statewide prevention trial, (3) generated a list of stakeholder informed interventions and outcomes to test in other future trials, and (4) participated as authors in multiple Health for Everyone in North Carolina study presentations and in a manuscript.12 Although the research team set up the initial practice-specific CABs and facilitated the discussions, participants who wanted to be part of the capstone meeting CAB helped to define the agenda. Several patients wanted to make sure there would be an opportunity, beyond guiding the research, to voice their opinions about general clinical operations with the practice members.

CAB 2: Parents and Teens Advising on Asthma Messaging.

In this example, two parent–teen dyads joined a group of six investigators and staff and collectively served on a 10-person CAB. While the investigators were thinking about grant ideas, a pediatric pulmonologist was asked to refer patient stakeholders who lived with persistent asthma who could help the team to generate grant ideas and methods. This CAB team ultimately decided to develop a set of videos to be viewed by parents and teens before pediatric asthma visits. The videos were designed to motivate teens to be more engaged in their visits, improve their confidence in being active participants in their care, and, for parents, to support the participation of teens at such visits.9 The on-going trial will examine if parent and teen exposure to the video content improves teen involvement during visits, medication adherence, and other outcomes. The parent–teen dyads are also involved in developing products of this work, such as disseminating the work via oral presentations, manuscripts, and by sharing the videos on YouTube and Facebook at the end of the trial.

CAB 3: The Monitor Trial Stakeholder Group: Patients, Providers, Public Health, Advocacy Groups, Industry, and Researchers with Diabetes Interests.

Stakeholders with an interest in diabetes came together with diabetes researchers to develop, implement, and ultimately disseminate findings of whether or not the use of home blood glucose monitoring among patients with type 2 diabetes (not on insulin) improves patient-centered and clinical outcomes. Stakeholders included patients with diabetes, clinical staff, public health professionals, diabetes educators, advocacy groups, and an industry partner (glucometer manufacturer). During the proposal development phase, researchers met with several community groups, refined the research question, and identified outcomes that mattered most to patients. A few members in several of these groups expressed interest in additionally meeting with the investigators to provide input on the study design. This group helped to refine the study design and identified additional patient-centered outcomes for inclusion. Members from these groups formed the 10-member stakeholder advisory board that provided regular input on study implementation and dissemination plans. Once formed, a lead stakeholder agreed to take on the responsibility of making sure that all voices were heard during each meeting. This was identified as a need after a study kick off meeting and led to an anonymous survey that was distributed to each CAB member after meetings. The survey gathered opinions as to how well stakeholders’ input felt valued and if they felt they had ample opportunity to speak during the meeting. Along with guiding the day-to-day research activities, the CAB members participated in (1) a national webinar on stakeholder engagement, (2) abstracts for regional and national conferences, (3) writing three manuscripts (currently under review), and (4) in some cases have used this experience to include more stakeholder-engaged methods in their own work.

CAB 4: Project Education and Access to Services and Testing.

The objective of the Project Education and Access to Services and Testing (Project EAST) was to understand how to better engage a variety of stakeholders in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS clinical trials, specifically how to increase the diversity of trial participants so that ultimately HIV/AIDS trial results would be more generalizable.7 The Project EAST team, including the 12-member CAB, aimed to identify, understand, and rectify multiple factors that influence attitudes about performing and participating in HIV/AIDS research. This CAB’s development is well-described by Isler et al.7 Briefly, the community members serving on this CAB was facilitated by local community outreach specialists who had longstanding leadership roles in the region’s HIV prevention and treatment work. The CAB included representation from grassroots, educational, media, political, human services, and faith-based organizations. In this case, the community and several of the UNC research team members had previous experience with working together, before the development of Project EAST. The CAB developed educational interventions, including a theatrical play aimed to reducing the stigma associated with having HIV, and other instructional methods to enhance the community’s knowledge regarding clinical trials and study participation.

CAB 5: The North Carolina Network Consortium Practice-based Research Advisory Board (Research Infrastructure Advisory Board).

The North Carolina Network Consortium (NCNC) is a statewide, practice-based research network (www.ncnc.unc.edu) partially supported by the UNC CTSA, and includes investigators from several health systems in NC. The NCNC Research Advisory Board (RAB) started in May 2015 out of the recognition that CARES and NCNC needed to expand clinician stakeholder representation and engagement in research. The NCNC RAB includes practicing clinicians and administrators from UNC Chapel Hill (11 members), Duke University (8), East Carolina University/Vidant Health (9), and the Carolinas Medical Center (6) who work in academic practices, community-based practices, or community health centers. NCNC RAB members guide the work of the NCNC, and also provide the clinician stakeholder view for developing research projects via surveys, email responses, and/or phone interviews. During the development of the NCNC RAB, clinicians and administrators provided input into what method and frequency of contact was preferred to gather clinician feedback on developing proposals and providing high-level guidance to NCNC. They also provided guidance on appropriate compensation and acknowledgement for their engagement work. Additionally, they suggested that we allow them to pass on investigator initiated surveys to other colleagues who could provide more relevant feedback. All of this advice was incorporated into the NCNC RAB standard processes.

CAB 6: UNC CTSA CABs: CABs Representing Diverse Stakeholders from Two Regions of North Carolina (Research Infrastructure Advisory Boards).

As part of the effort to engage with communities and community representatives in the translational research at UNC Chapel Hill, the UNC CTSA’s leadership supported the development of two regional 15-member CABs in North Carolina: one included community advisors in the Greensboro area (Greensboro CAB) and the other from the central part of the state (Wake CAB). CAB members represent community advocacy groups, faith-based organizations, public health professionals. Much of the engagement of these CAB members and UNC researchers occurs in the pre-award phase where CAB members guide investigators in understanding how to engage with communities in all aspects of their research. Some CAB members choose to be included in study-specific CABS once funded. The actual development and implementation of these CABs regarding their charter, governance, and other operational issues was facilitated by CARES staff members, but decision making and planning were led by the community stakeholders. Policies and documents created by the community members included those addressing (1) responsibilities for board officers, (2) board members agreements, and (3) purpose and guideline documents, and certificates of appreciation for CAB participation.

Description of Key Contextual Domain 5: Common Challenges/Solutions/Outcomes: Compensation—CAB/RAB Financial Compensation Within a University Setting

There are many challenges to compensating CAB members for their time investment, some of which are described herein. Additionally, for investigators in the pre-award period, there are often barriers to accessing funds to use to pay community members or even university affiliated health care provider stakeholders in this manner.

Administrative Burdens.

Most CAB members need to fill out complex and befuddling independent contractor forms and invoices to receive payment. In addition, there are often long waiting periods for payments to reach CAB members. More recently, the university also required criminal background checks for all contractors, including CAB members, which understandably has not been well received by many CAB members and excludes a population that may be valuable to guide specific projects. To address these issues, the PRIME collective, the group of experienced CAB members mentioned in the Methods section, and CARES research staff worked to mitigate these challenges by establishing “work arounds” for payment issues. In some cases, providing gift cards was less challenging than sending checks. The PRIME collective LLC now serves as a university vendor and fiscal agent that, in addition to allowing for faster processing of payments to CAB members, also obviates the need to have the university personnel perform background checks. Additionally, the UNC CTSA has designed a voucher system where investigators can apply for up to $2,000 to cover the costs of CAB consultations.13

Unique Populations: Children and Teens.

Payment mechanisms are uniquely challenging for minors and compensation rules can differ by age (i.e., policies for 14-year-olds vs. 17-year-olds can vary; thus, as youth CAB members age in research projects, the compensation rules that apply to them can change, a process influenced by child labor laws). In one case, when a parent and a minor were in a CAB together, the parent or guardian that was not involved in the CAB needed to sign a document stating their permission to compensate the minor.

Scheduling Conflicts and Communication Methods.

As expected, it is challenging to find a regular time for CAB meetings that worked for all members, especially in multiyear studies. Many groups acknowledged the benefit of face-to-face meetings, especially in the early phases of relationship building, but over time phone conference calls or even individual calls with CAB members were necessary to keep CAB members involved and apprised of research activities. Phone-based calls are preferred to using video conference resources that in general required CAB members to have access to computers. Of note, regarding scheduling, minors have various restrictions regarding the time of day and hours they could engage in CAB activities, especially if school is in session.

Allowing Time for Relationship Building and Culture Change.

In most of the CAB cases, stakeholders and researchers or clinicians are meeting together to jointly focus on health issues. In general, it takes several meetings, over 6 to 12 months, for CAB member to feel that they had an equal and valued voice in research teams.

Managing Intellectual Property Issues.

In cases where industry partners are involved, some of whom had product development interests as part of the work with CABs, it is necessary to address confidentiality and intellectual property rights. In one case, the university legal staff members worked with the research team and CAB members to prepare stakeholder advisory board confidentially agreements, one for industry members and one for the other CAB members to address these concerns.

DISCUSSION

We worked across our CTSA-supported CARES group and affiliated community members to create a shared understanding of the experiences our CARES members have had with CABs to collaboratively understand what overarching key contextual domains are important to consider when developing and implementing research CABs. We agreed on five key contextual domains that best describe the experiences to establish a best practice approach to counseling others on CAB creation and maintenance. We found these key contextual domains to be relevant across CAB groups regardless of the different ages, race groups, geographic settings, and research interests of the CAB members.

We found the process of agreeing on contextual domains to be relatively smooth, likely owing to having many CARES team members who work directly with or on CABS as part of a long history of using principles of community-based participatory research in much of our health services research work at UNC Chapel Hill.

Our CARES team members believe that successful collaborations with CABs require that groups work together with shared power to explore their respective missions and motivations to address health issues in their communities. These collaborations need to have supportive infrastructure, including financial resources and investments in human capital. We advise that CABs clearly articulate and agree on specific activities and roles of CAB members to reduce uncertainties as to how individuals can contribute to the whole. We recommend early engagement with university staff and officials to work to understand how to most seamlessly engage and compensate community stakeholders and to consider policy changes to ease the current administrative burdens that negatively impact engaged research.

We are not aware of any prior work done in the area contextual descriptions of research CAB experiences. However, others have called on the research community to report deeper contextual descriptions in manuscripts and other dissemination vehicles to help researchers enhance their understanding of the relevance, generalizability, and translational potential of research findings to different patient populations and environments.11,14-16 Additionally, providing more context has the potential to provide additional explanation for variability in outcomes and insights into what adaptations may improve processes going forward.17

LIMITATIONS

This was an explorative exercise on a small number of CABs affiliated with work of a single CTSA institution; thus, the results should be considered accordingly. UNC’s deep involvement in community-based participatory research is both an asset, but also a potential limitation, in generalizing our experiences to other institutions that may have with fewer local champions and leaders for community-based participatory research or that are guided by different methods of community-engaged research.

Although several of the CABs are ongoing, the specifics of the CAB experiences were gathered retrospectively and by a few members of each CAB. A more comprehensive and prospective approach could result in a different set of recommended contextual domains. However, when this work was presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group meeting in July 2016, multiple research teams working in the stakeholder engagement space were working on similar types of methods to categorize their experiences. One noted clinician and health services researcher shared his “five Rs” categories of successful work with CABs, which are Respect, Resources, Roles, Responsibilities, and Requirements, which reassuringly map well to our domains (personal communication, Chester Fox, MD, 2016 July 11).

Like in the work by Tomoaia-Cotisel et al.11 where theoretical frameworks were entertained and explored for a fit with this kind of work, but ultimately not chosen owing to a lack of fit, we did not find it natural or logical to embed the current work in any existing frameworks or theories. However, going forward and in a prospective design, we would explore the implementation frameworks, such as the consolidated framework for implementation research as a guide.18

CONCLUSiONS

We share the experiences of six research CABS supported by our CTSA and describe their work by using five iteratively agreed upon contextual domains to organize the case descriptions and a final list of “tips” for those venturing to work with CABs in translational research. It is hoped that, by sharing the respective motivators, operational processes, supportive resources, activities, and challenges faced by these CABS, the relevance of this work may be more evident to others attempting to develop and support CABs for their own projects and/or research organizations. We encourage the further use and adaption of these factors as others venture into CAB supported work and the work to enhance the evidence base of the effectiveness of this kind of stakeholder engagement. Ultimately, with expanded understanding and evaluation of research that is guided by CABs, we can then move beyond descriptions and onto the development of measures and methods to test the impact of CABs and what aspect of CAB work best influences improved health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant Award Number 1UL1TR001111. Dr. Giselle Corbie-Smith was also supported by K24HL105493. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors thank Dr. Timothy Carey, Dr. Andrea Carnegie, Dr. Lori Carter-Edwards, and the PRIME collective for help with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res 2012;1:181–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA 2014;312:1513–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC, et al. The role of community advisory boards: Involving communities in the informed consent process. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1938–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodare H, Lockwood S. Involving patients in clinical research improves the quality of research. BMJ 1999;319:724–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn SC. Protecting human subjects: The role of community advisory boards. Am J Public Health 2004;94:918–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isler MR, Miles MS, Banks B, et al. Across the miles: process and impacts of collaboration with a rural community advisory board in HIV research. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2015;9:41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbie-Smith G, Odeneye E, Banks B, et al. Development of a multilevel intervention to increase HIV clinical trial participation among rural minorities. Health Educ Behav 2013;40:274–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Lee C, et al. The development of an educational video to motivate teens with asthma to be more involved during medical visits and to improve medication adherence. J Asthma 2016;53:714–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Scammon D, Waitzman N, et al. Context matters: the experience of 14 research teams in systematically reporting contextual factors important for practice change. Ann Fam Med 2013;11(Suppl 1):S115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halladay JR, Vu M, Ripley-Moffitt C, et al. Patient perspectives on tobacco use treatment in primary care. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NC TraCS offers new $2K voucher to support stakeholder engagement [Internet] Chapel Hill: The North Carolina Network Consortium (NCNC) [cited 2016 Aug 3] Available from: http://ncnc.unc.edu/news/nc-tracs–2k-voucher [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28:413–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green LW, Glasgow RE, Atkins D, et al. Making evidence from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning, and practice: Slips “twixt cup and lip.” Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6 Suppl 1):S187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, et al. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med 2005;29(Suppl):66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE. Review of external validity reporting in childhood obesity prevention research. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]