Abstract

The vaccines developed against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 are seen as the most crucial weapon in controlling the epidemic. It has been reported in early-stage vaccine studies that vaccines provide up to 95% protection against severe disease and mortality, even in the absence of symptomatic infection. Reports on vaccine breakthrough infections that developed after widespread vaccination are available in the literature. In addition to the general population, the course of vaccine breakthrough infections in immunocompromised patients is a matter of concern. This case report aimed to define severe coronavirus disease 2019 developing in a lung recipient who received 3 doses of inactivated virus vaccine.

Although almost 2 years have passed since the first case was detected and despite ongoing social isolation measures and the widespread use of vaccines, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to cause morbidity and mortality worldwide. Re-infections and vaccine breakthrough infections are reported with a frequency that cannot be called sporadic. Immunocompromised patients are given priority in vaccination programs in our country, as in the rest of the world. The actual rate and prognosis of vaccine breakthrough infections in this patient group is a matter of curiosity. Lung recipients constitute a unique group among immunocompromised patients. Both the intensive use of immunosuppressants and the fact that the main target of the pandemic agent is allograft create concerns about the course of COVID-19 in lung recipients [1]. There are few reports in the literature on vaccine breakthrough infections in lung recipients. The present report aims to define a severe case of COVID-19 in a lung recipient vaccinated with 3 doses of Sinovac (Sinovac Life Sciences, Beijing, China), one of the vaccines approved for emergency use by the World Health Organization.

Case

A 62-year-old male patient who had a double lung transplant 42 months ago because of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was vaccinated with 2 doses of Sinovac in January 2021. In his routine tests 2 months later, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein-specific immunoglobulin (IgG and IgM) was found to be low positive in the serum. The patient was vaccinated with a third dose of Sinovac in July. Seven weeks after the third dose of Sinovac, the patient, who developed shivering and fever, went to the emergency department. The patient's oxygen saturation was measured as 96 in room air, with a temperature of 36.2°C, pulse rate of 80/min, and respiratory rate of 14/min. Chest x-ray was evaluated as normal, and a SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test from a nasopharyngeal swab was positive. The patient had moderate symptoms and was followed up on an outpatient basis. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment was interrupted, and favipiravir (2 × 1600 mg loading on the first day, 2 × 600 mg on the next 4 days) and paracetamol were prescribed. The patient, who developed dyspnea on the third day after diagnosis, again went to the emergency department. Oxygen saturation was 92 in room air, heart rate was 96/min, and respiratory rate was 18/min. The patient was transferred to our center with the current findings. Respiratory examination revealed bilateral wheezing. Throat, tracheal aspirate, and blood and urine cultures were taken. Cytomegalovirus and Aspergillus DNA polymerase chain reaction and galactomannan antigen tests from tracheal aspirate and serum samples were negative. Subsegmental atelectasis and bilateral multifocal ground-glass areas predominantly located peripherally were detected on thorax computed tomography (Fig 1 ). Nasal oxygen at 4 L/min, empirical antibiotics (meropenem 2 × 1000 mg), ascorbic acid (2 × 500 mg), enoxaparin sodium (2 × 40 mg), and methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg-day) were started. The patient was hospitalized and followed up in the COVID-19 service. There was no growth in the throat, tracheal aspirate, or blood and urine cultures. High-flow oxygen therapy was started on the third day of hospitalization because the patient's respiratory failure gradually increased. Pulse steroid therapy (3 × 1000 mg/day methylprednisolone, gradually reduced to maintenance dose) was planned. Voriconazole (2 × 200 mg), amphotericin-B (3 × 10 mg with a nebulizer), and ganciclovir (2 × 200 mg) were started empirically. Because respiratory failure could not be managed despite high-flow oxygen therapy, invasive mechanical ventilation was applied. The patient died on the 19th day of hospitalization of multiorgan failure and septic shock. Delta variant was detected in the naso-oropharyngeal swab sample.

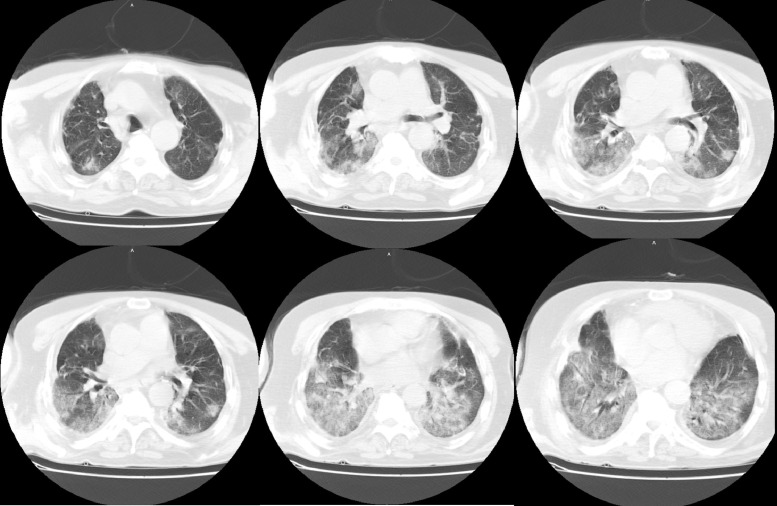

Fig 1.

Subsegmental atelectasis and bilateral multifocal ground-glass areas are seen on thorax computed tomography, which was examined 3 days after the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 diagnosis.

Discussion

Widespread use of effective and safe vaccines is a crucial factor in ending the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Health Organization has given emergency use approval to various SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [2]. Satisfactory results were reported in the first phase 3 studies of Sinovac, one of the vaccines approved for emergency use. The Sinovac vaccine was reported to be 51% to 65% protective against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and 90% to 100% protective against severe illness and hospitalization in the immunocompetent population [2,3]. Although early results show that vaccines protect against especially severe diseases, severe COVID-19 disease and deaths have started to be seen despite vaccines. A phase 3 study conducted with the Sinovac vaccine in Chile reported that the vaccine was 85% protective against hospitalization due to COVID-19 and 80% protective against COVID-19-related death [2].

One of the important causes of vaccine breakthrough infections is the low neutralizing antibodies after vaccination. The vaccine response is expected to be low, especially in the elderly population and immunosuppressed patients [4]. However, the literature has also reported that vaccine breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection is seen despite high neutralizing antibodies [5]. Immune escape mutations in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 are highly likely to cause re-infection and vaccine breakthrough infections. Currently, the World Health Organization describes 4 variants as variants of concern, labeled alpha, beta, gamma, and delta [6]. Vaccine breakthrough infections seen in the community with SARS-CoV-2 variants that are more contagious, cause more severe disease, and have decreased neutralization with antibodies due to previous disease or vaccination are reported with a frequency that cannot be called sporadic. High mortality rates ranging from 14% to 34% have been reported in studies on COVID-19 in lung recipients, though there are few in the literature [7], [8], [9]. The success of promising treatments such as convalescent plasma, tocilizumab, and anakinra in the early stages of the pandemic has not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials [10], [11], [12], [13]. The lack of an effective treatment regimen raises concerns about vaccine efficacy and infections with mutant SARS-CoV-2 variants in lung recipients, as in other immunosuppressed patients [14]. Due to immunosuppressants, the antibody response may be low, and the risk of vaccine breakthrough infection is higher in these patients than in the general population.

In its consensus document published on August 13, 2021, International Society of Hearth and Lung Transplantation recommended administering a third dose of COVID-19 vaccine to patients undergoing thoracic organ transplantation, regardless of neutralizing antibody level [15]. In our country, only inactivated virus vaccine has been available since the last months of 2020. Therefore, 2 doses of inactivated virus vaccine were administered to lung recipients. Although mRNA vaccines were also provided and recommended to lung recipients, some preferred the inactivated virus vaccine for the third dose. This case is unique in that 3 doses of inactivated virus vaccine were administered. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case reported in the English literature of a vaccine breakthrough infection in a lung recipient after 3 doses of inactive virus vaccine.

Thus, the efficacy of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in lung recipients may be far below expectations. Although the SARS-CoV-2 infection that develops in these patients starts with mild symptoms, it can progress rapidly. Even if the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is fully administered in lung recipients, isolation measures should not be compromised.

Footnotes

Informed consent was obtained from the relatives of the patients.

References

- 1.Turkkan S, Beyoglu MA, Sahin MF, et al. COVID-19 in a lung transplant patient: rapid progressive chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Exp Clin Transplant. 2021 doi: 10.6002/ect.2020.0563. [e-pub ahead of print] accessed April 29, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.<https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccinesSAGE_recommendation-Sinovac-CoronaVac-2021.1>; [accessed 12.10.21].

- 3.Hitchings MDT, Ranzani OT, Torres MSS, de Oliveira SB, Almiron M, Said R, et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac in the setting of high SARS-CoV-2 P.1 variant transmission in Brazil: a test-negative case-control study. MedRxiv. 2021 <https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.07.21255081v1>; [accessed 26.04.21]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Understanding immunosenescence to improve responses to vaccines. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:428–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulte B, Marx B, Korencak M, et al. Case report: infection with SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of high levels of vaccine-induced neutralizing antibody responses. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.704719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.<https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/>; [accessed 12.10.21].

- 7.Messika J, Eloy P, Roux A, et al. COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2021;105:177–186. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kates OS, Haydel BM, Florman SS, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant: a multi-center cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1097. [e-pub ahead of print] accessed August 7, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aversa M, Benvenuto L, Anderson M, et al. COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients: a single center case series from New York City. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:3072–3080. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balcells ME, Rojas L, Le Corre N, et al. Early versus deferred anti-SARS-CoV-2 convalescent plasma in patients admitted for COVID-19: a randomized phase II clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta M, Purpura LJ, McConville TH, et al. What about tocilizumab? A retrospective study from a NYC hospital during the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosas IO, Bräu N, Waters M, et al. Tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1503–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CORIMUNO-19 Collaborative Group Effect of anakinra versus usual care in adults in hospital with COVID-19 and mild-to-moderate pneumonia (CORIMUNO-ANA-1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:295–304. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turkkan S, Beyoglu MA, Sahin MF, Yazicioglu A, Tezer Tekce Y, Yekeler E. COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients: a single-center experience. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021:e13700. doi: 10.1111/tid.13700. [e-pub ahead of print] accessed July 29, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.<https://ishlt.org/ishlt/media/documents/ISHLT-AST_SARS-CoV-2-Vaccination_8-13-21.pdf>; [accessed 12.10.21].