Abstract

Objectives:

To explore pre-operative factors and their impact on overall survival (OS) in a modern cohort of patients who underwent pelvic exenteration (PE) for gynecologic malignancies.

Methods:

A retrospective review was performed for all patients who underwent a PE from 1/1/2010 through 12/31/2018 at our institution. Inclusion criteria were exenteration due to recurrent or progressive carcinoma of the uterus, cervix, vagina or vulva, with histologically confirmed complete surgical resection of the malignancy. Exclusion criteria included PE for palliation of symptoms without recurrence, and for ovarian or rare histologic malignancies. Univariable and multivariable analysis were performed to identify factors predicting prolonged survival.

Results:

Overall, 71 patients met the inclusion criteria. Median age at time of exenteration was 62 years (range, 28–86 years). Vulvar cancer was the most common primary diagnosis (32%); 30% had cervical cancer; 23%, uterine cancer; 15%, vaginal cancer. Median OS was 55.1 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 36-not estimable) with a median follow-up time of 40.8 months (95% CI: 1–116.1). On univariable analysis, age >62 years (hazard ratio (HR) 2.71, 95% CI 1.27–5.79), American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) 3–4 (HR: 3.41 (95% CI 1.03–11.29), and vulvar cancer (HR 4.19 (95% CI 1.17–14.96) predicted worse OS. Tumor size and prior progression-free interval (PFI) did not meet statistical significance in OS analyses. On multivariable analysis, there were no significant factors associated with worse OS.

Conclusions:

PE performed with curative intent may be considered a treatment option in well-counseled, carefully selected patients, irrespective of tumor size and PFI before exenteration.

Keywords: Pelvic exenteration, Recurrent disease, Gynecologic malignancy

Introduction

Pelvic exenteration (PE) was first described at our institution in 1948, as a mostly palliative procedure for advanced cancers affecting the pelvic viscera 1. A PE is an en bloc resection intended to remove the pelvic organs for centrally located tumors. The procedure was associated with significant morbidity and mortality 1. Over the last 70 years, due to improvements in preoperative planning, perioperative care, and reconstructive techniques, PE has evolved to encompass curative intent for appropriately selected candidates with recurrent or progressive carcinoma of gynecologic origin 2,3.

Despite improved surgical techniques, perioperative care, and curative intent, reported 5-year survival rates range from 33–57% 4–8. PE significantly impacts the patient’s quality of life 9, with high rates of morbidity 10. Previous studies have investigated specific clinical and histopathologic factors that may be associated with improved survival. Historically, candidates for the procedure had a small, centralized recurrence (<3 cm) and were at least 1 year from previous radiation therapy 5. More recently, close or positive margin status and lymph node metastasis have been reported to be the strongest predictors of recurrence and worse overall survival (OS) 11,12. Advances in preoperative planning include imaging modalities such as whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) using 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) 13,14, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 15, which detect radiation-induced changes, pelvic organ invasion, and the presence of extra-pelvic disease. In light of recent advances in pre-operative planning, the impact on OS of clinical and histopathologic factors such as patients’ age, performance status, tumor size, and interval from previous treatment to exenteration, are being explored.

Here we describe a modern cohort of patients who underwent PE for progressive or recurrent gynecologic malignancies. We explore the impact of clinical and histopathologic factors on OS and progression-free survival (PFS).

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Our institution offers a PE procedure to patients who have centralized or lateral pelvic recurrence of a gynecologic malignancy without evidence of extra-pelvic disease. Most patients undergo preoperative imaging with PET-CT and pelvic MRI to assess the extent of disease. Incorporated into the preoperative planning is a multidisciplinary conference, during which specific cases are reviewed by specialists from the Surgery, Radiology, Genetics, Medical Oncology and Urology Services.

A retrospective review of the records of all patients who underwent a PE for a gynecologic malignancy at MSKCC from January 1, 2010 until December 31, 2018 was performed. Data regarding the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, histopathologic data, operative outcomes, and disease status were collected from the electronic medical records. The procedures were classified as anterior, posterior, or total exenterations.

Patients were included if they underwent a PE due to recurrent or progressive carcinoma of the uterus, cervix, vagina or vulva, without any evidence of microscopic disease at the tumor margins (defined as R0) on final pathologic report 16. Patients were excluded if they underwent a PE for palliation of symptoms without recurrence of malignancy or if they had microscopically positive margins on final pathology. Patients with ovarian or rare histologic malignancies were also excluded.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort. As most patients undergoing this procedure have had multiple prior recurrences and treatment modalities, the progression-free interval (PFI) prior to exenteration was defined from the starting date of treatment immediately preceding the recurrence or progression of disease, to the time of diagnosis of recurrence. PFS was calculated from the date of exenteration to date of progression, date of last follow-up, or date of death. OS was calculated from the date of exenteration to date of death or last follow-up. Kaplan-Meier analyses were performed for PFS and OS to obtain the median survival and survival rates. In univariate analysis, the Log-rank test/Wald test based on the Cox proportional hazards (CoxPH) model were applied to obtain the p-value for significant variables, depending on categorical or continuous variables. All univariables with a p-value <0.05 were included in the multivariate CoxPH models. The following factors were included: age at the time of exenteration, primary diagnosis, American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) status, PFI prior to exenteration, and tumor size. A dichotomous variable for age was created based on the median age of the cohort. ASA was clustered to form two categorical groups as 1–2 versus 3–4. Tumor size was also categorical (<30 mm, and ≥30 mm), based on final pathology.

Results

During the study period, 83 patients were identified; 71 of these met the inclusion criteria. Twelve patients were excluded for the following reasons: 2 patients underwent PE due to severe symptoms secondary to fistulas, and 2 due to rare histologies (1 patient for a uterine smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential, and the other for a leiomyosarcoma). The remaining 8 excluded patients had R1 status on histology.

The median age of the cohort at the time of PE was 62 years. Vulvar cancer was the most common primary diagnosis (n=23, 32%); 21 patients (30%) had cervical cancer, 16 (23%) had uterine cancer, and 11 (15%) had vaginal cancer. The most common histology was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (n=43, 61%), followed by endocervical adenocarcinoma (n=13, 18%), as presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the population

| Characteristic | N =71 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age at exenteration, years (range) | 62 (28–86) |

| BMI, median kg/m2 (range) | 27 (17–50) |

| Race, N (%) | |

| White | 62 (87) |

| Black | 3 (4.2) |

| Asian | 3 (4.2) |

| Unknown | 3 (4.2) |

| Primary diagnosis, N (%) | |

| Vulvar | 23 (32) |

| Cervical | 21 (30) |

| Uterine | 16 (23) |

| Vaginal | 11 (15) |

| Primary Histologic Diagnosis, N (%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 43 (61) |

| Endocervical Adenocarcinoma | 13 (18) |

| Endometrioid Endometrial Carcinoma | 11 (15) |

| Adenosarcoma | 3 (4.2) |

| Serous carcinoma | 1 (1.4) |

| Preoperative ASA Class, N (%) | |

| 1 | 2 (2.8) |

| 2 | 13 (18) |

| 3 | 52 (73) |

| 4 | 4 (5.6) |

BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists

Sixty-nine patients (97.2%) had centrally located lesions. Two patients (2.8%) had lesions that extended laterally, and therefore underwent a laterally extended endopelvic resection (LEER) during their exenteration procedure. Forty-seven patients (66%) had a total PE; 17 patients (24%) underwent an anterior exenteration; and 5 (7%) underwent a posterior exenteration. The median operative time was 543 minutes (range 221–973 minutes), with a median estimated blood loss (EBL) of 700 mls (range, 100–3000 mls). The median PFI before exenteration was 13 months (range, 0–259 months). Most tumors were ≥3 cm in size (n=53, 76%) on final pathology; 17 patients (24%) had tumors measuring <3 cm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operative and histopathologic outcomes of patients who underwent pelvic exenteration procedures

| Operative Outcomes | |

|

| |

| Operative time | 543 min (221–973 min) |

| EBL | 700 mL (100–12,000 mL) |

| Intraoperative transfusion | 25 (35.0) |

| Type of Exenteration | n (%) |

| Total | 47 (66) |

| Anterior | 22 (27.5) |

| Posterior | 5 (6.25) |

| Tumor size, median (range) | 41 mm (4–156 mm) |

EBL, Estimated Blood Loss

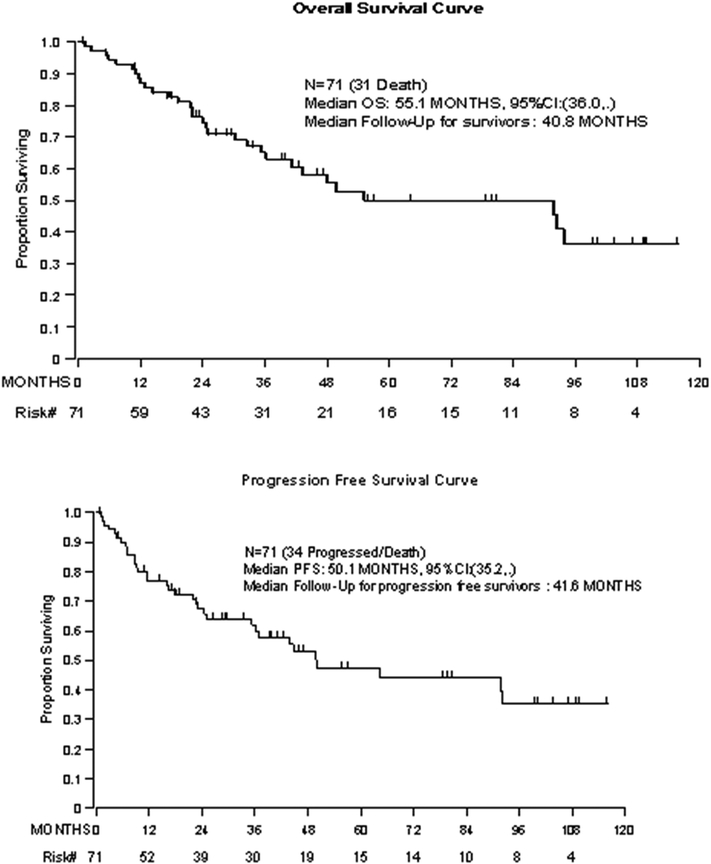

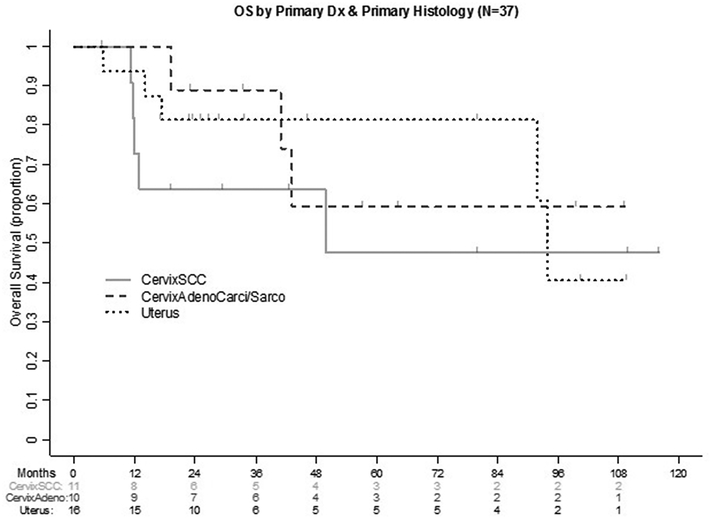

The median PFS was 50.1 months (95% CI: 35.2-not estimable), and median OS was 55.1 months (95% CI: 36.0-not estimable). Survivors had a median follow-up of 3.4 years (Figure 1). A sub-analysis was performed stratifying patients by primary disease location and histologic subtype to determine their OS (Figure 2). Patients with SCC of the cervix (n=11) had a median OS of 49.9 months (95% CI: 11.5-not estimable); patients with endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (n=16) had a median OS of 93.9 months (95% CI: 91.9-not estimable); in patients with cervical adenocarcinoma or adenosarcoma, median OS was not reached. For patients who had a primary diagnosis of vulvar carcinoma, the median OS was 24.8 months (95%CI: 21.4–55.1) (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall survival and progression-free survival for the population

Figure 2:

Sub analysis for OS based upon disease location and histologic type

On univariable analysis, OS was negatively impacted by age >62 years (HR: 2.71 (95% CI 1.27–5.79)), diagnosis of vulvar carcinoma (HR: 4.19 (95% CI 1.17–14.96)), and ASA class of 3 or 4 (HR: 3.41 (95% CI 1.03–11.29)). On multivariable analysis, none of the factors had a negative impact on OS (Table 3). PFI before the exenteration, and tumor size, did not meet statistical significance in the univariable analysis for OS. Variables that impacted PFS were age >62 years (HR: 2.04 (95% CI 1.02–4.08)), and vulvar carcinoma (HR: 4.27 (95% CI 1.21–15.1). On multivariate analysis, these factors did not show statistical significance with respect to PFS (Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable analysis for overall survival in the whole cohort

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Age at exenteration >62 years | 2.71 | 1.27–5.79 | 0.008 | 2.31 | 0.86–6.22 | 0.10 |

| Primary Diagnosis | ||||||

| Vulvar | 4.19 | 1.17–14.96 | 0.016 | 3.30 | 0.91–12.0 | 0.14 |

| Cervical | 1.53 | 0.4–5.76 | 2.56 | 0.60–11.0 | ||

| Uterine | 1.28 | 0.31–5.38 | 1.24 | 0.29–5.22 | ||

| Vaginal | 1 | - | - | - | ||

| Preoperative ASA class | ||||||

| 3–4 | 3.41 | 1.03–11.29 | 0.033 | 2.40 | 0.69–8.33 | 0.17 |

| PFI before exenteration | ||||||

| >6 months | 0.45 | 0.19–1.07 | 0.063 | - | - | - |

| > 12 months | 0.51 | 0.25–1.06 | 0.066 | - | - | - |

| Tumor Size | ||||||

| >29mm | 2.07 | 0.79–5.41 | 0.129 | - | - | - |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; PFI, progression-free interval; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable analysis for progression-free survival in the whole cohort

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Age at exenteration >62 years | 2.04 | 1.02–4.08 | 0.04 | 2.05 | 0.85–4.96 | 0.11 |

| Primary Diagnosis | ||||||

| Vulvar | 4.27 | 1.21–15.1 | 0.032 | 3.70 | 1.03–13.3 | 0.12 |

| Cervical | 1.99 | 0.55–7.25 | 2.82 | 0.71–11.2 | ||

| Uterine | 1.58 | 0.39–6.32 | 1.56 | 0.39–6.27 | ||

| Vaginal | 1 | - | - | - | ||

| Preoperative ASA class | ||||||

| 3–4 | 2.59 | 0.91–7.36 | 0.65 | |||

| PFI before exenteration | ||||||

| >6 months | 0.49 | 0.21–1.14 | 0.092 | - | - | - |

| >12 months | 0.56 | 0.28–1.12 | 0.097 | - | - | - |

| Tumor Size | ||||||

| >29 mm | 1.96 | 0.81–4.73 | 0.13 | - | - | - |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; PFI, progression-free interval

Discussion

In patients who have a pelvic recurrence or progression of gynecologic malignancies, treatment options are limited. These tumors are not amenable to additional radiation therapy, given their location and prior treatment, and they have poor response to chemotherapy 4. As such, a salvage surgical resection is frequently the only option. In this study of patients who underwent an exenteration procedure resulting in negative histologic margins, the median OS was 4.6 years, which is comparable to previously published 5-year OS rates (33–57% 4–8).

The duration from prior treatment to recurrence has been shown to be an important prognostic factor for OS. Patients who recur rapidly are thought to have more aggressive tumors and may not receive long-term benefit from an exenteration procedure, which entails significant morbidity. A study of 44 patients who developed a gynecologic recurrence and underwent exenteration demonstrated that patients whose recurrence arose more than two years from the time of their prior chemoradiation had significantly longer survival than those who recurred within two years (33 months vs. 8 months, p=0.016) 17. In our models, time from prior treatment to recurrence before exenteration did not show significance with respect to OS or PFS analyses at 6 months and 12 months. These findings concur with those of Westin et al., who reported on 160 patients undergoing exenteration for gynecologic malignancy. In their multivariable analysis, time from treatment to exenteration did not have a significant impact on recurrence 18. These findings may indicate that time from prior treatment to recurrence may have less impact on survival outcomes alone. If this is the case, it would allow for a broadening of the eligibility criteria for PE when other treatment modalities have been exhausted.

In determining which patients may benefit from PE, the optimal threshold of recurrent tumor size has been debated. Theoretically, larger tumors are potentially more challenging to dissect, making negative surgical margins less likely. In a study of women who underwent PE for gynecologic, urologic, or colorectal indications, the risk of positive margins increased by 11% for every 1 cm increase in tumor size 11. Shingleton et al. found that patients with tumors measuring <3 cm were most likely to have long-term OS5. In another review of 107 patients who underwent exenteration for primary or recurrent gynecologic malignancies, however, tumors >5 cm did not correlate with risk of death or risk of recurrence 19. Our findings also indicate that tumor size itself may have less of an impact on OS and PFS when negative margins are achieved.

In the present study, vulvar lesions were more likely to recur (HR: 3.70 (95% CI 1.03–13.3) compared with other primary sites of disease. Patients with vulvar cancer have been shown to have a lower OS compared with patients with cervical cancer 20. Westin et al. also demonstrated that patients with vulvar carcinoma have a lower OS than patients with cervical, vaginal, or endometrial carcinoma 18. Further research in this area is needed.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the only study to date that has investigated clinical and histopathologic features in a cohort of patients undergoing PE with negative margins on final pathology. This large cohort of patients enabled us to use multivariable modeling to facilitate interpretation of associations and reduce biases. The period covered in this study is relatively short, and the study was conducted during the era of modern imaging techniques and multidisciplinary treatment planning.

This study has several limitations. A heterogenous population of primary tumors and histology was examined, which may impact generalization of the results for each specific subtype, as the sample sizes are small. Our institution is a high-volume tertiary care center, and the results may not be applicable to all institutions. (Mortality from this procedure is known to improve when patients are treated at high-volume specialty centers 21). This study also has limitations inherent to all retrospective analyses, as the results and survival outcomes are reliant upon the electronic medical record.

In conclusion, patient eligibility for PE may be broader than previously thought. When complete resection is the likely operative result in the setting of a centrally located lesion, tumor size and previous preoperative PFI may have less impact on OS in carefully counseled and well-selected surgical candidates. Given the rarity of these surgeries and the associated morbidity and mortality, these patients should be treated at high-volume surgical specialty centers that have the multidisciplinary clinical expertise to care for them. Development of a national registry of such cases may facilitate further identification of patients likely to benefit from this procedure.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Overall survival by primary disease location

Highlights.

Median overall survival after pelvic exenteration for gynecologic was 55 months when R0 margins were achieved.

Tumor size and progression-free interval before exenteration may have less impact on survival when R0 margins are achieved.

Median overall survival for patients who underwent pelvic exenteration for recurrent vulvar cancer was 25 months.

Funding:

This study was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Disclosures: NRA reports the following, outside the submitted work: grant from Stryker/Novadaq (paid to institution); grant from Olympus (paid to institution); grant from GRAIL (paid to institution). Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) has financial interests relative to GRAIL. As a result of these interests, MSK could ultimately potentially benefit financially from the outcomes of this research. AI is a consultant for Mylan and reports personal fees from Mylan, outside the submitted work. ELJ is a consultant for Intuitive Surgical Inc., outside the submitted work; she is an educational speaker and consultant for Covidien/Medtronic and reports personal fees from Cofidien/Metronic, outside the submitted work. MML is a consultant for Intuitive Surgical Inc., outside the submitted work. AMS has a patent (W02019195097A1, perineal heating device) issued, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brunschwig A. Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma. A one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer 1948;1(2):177–183. DOI: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambrou NC, Pearson JM, Averette HE. Pelvic Exenteration of Gynecologic Malignancy: Indications, and Technical and Reconstructive Considerations. Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America 2005;14(2):289–300. DOI: 10.1016/j.soc.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakhman Y, Nougaret S, Miccò M, et al. Role of MR Imaging and FDG PET/CT in Selection and Follow-up of Patients Treated with Pelvic Exenteration for Gynecologic Malignancies. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc 2015;35(4):1295–1313. (In eng). DOI: 10.1148/rg.2015140313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma S, Odunsi K, Driscoll D, Lele S. Pelvic exenterations for gynecological malignancies: Twenty-year experience at Roswell Park Cancer Institute. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2005;15(3):475–482. (Review). DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shingleton HM, Soong S-J, Gelder MS, Hatch KD, Baker VV, Austin MJ. Clinical and Histopathologic Factors Predicting Recurrence and Survival After Pelvic Exenteration for Cancer of the Cervix. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1989;73(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Symmonds RE, Pratt JH, Webb MJ. Exenterative operations: Experience with 198 patients. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1975;121(7):907–918. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90908-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg GL, Sukumvanich P, Einstein MH, Smith HO, Anderson PS, Fields AL. Total pelvic exenteration: The Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center Experience (1987 to 2003). Gynecologic Oncology 2006;101(2):261–268. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutledge FN, Smith JP, Wharton JT, O’Quinn AG. Pelvic exenteration: Analysis of 296 patients. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1977;129(8):881–892. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90521-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dessole M, Petrillo M, Lucidi A, et al. Quality of Life in Women After Pelvic Exenteration for Gynecological Malignancies: A Multicentric Study. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer 2018;28(2):267. DOI: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benn T, Brooks RA, Zhang Q, et al. Pelvic exenteration in gynecologic oncology: A single institution study over 20 years. Gynecologic Oncology 2011;122(1):14–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith B, Jones EL, Kitano M, et al. Influence of tumor size on outcomes following pelvic exenteration. Gynecologic Oncology 2017;147(2):345–350. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seagle BLL, Dayno M, Strohl AE, Graves S, Nieves-Neira W, Shahabi S. Survival after pelvic exenteration for uterine malignancy: A National Cancer Data Base study. Gynecologic Oncology 2016;143(3):472–478. (Article) (In English). DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burger IA, Vargas HA, Donati OF, et al. The value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in recurrent gynecologic malignancies prior to pelvic exenteration. Gynecologic oncology 2013;129(3):586–592. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husain A, Akhurst T, Larson S, Alektiar K, Barakat RR, Chi DS. A prospective study of the accuracy of 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG PET) in identifying sites of metastasis prior to pelvic exenteration. Gynecologic Oncology 2007;106(1):177–180. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donati OF, Lakhman Y, Sala E, et al. Role of preoperative MR imaging in the evaluation of patients with persistent or recurrent gynaecological malignancies before pelvic exenteration. European Radiology 2013;23(10):2906–2915. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-013-2875-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermanek P, Wittekind C. The Pathologist and the Residual Tumor (R) Classification. Pathology - Research and Practice 1994;190(2):115–123. DOI: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80700-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean KA, Zhang W, Dunsmoor-Su RF, et al. Pelvic exenteration in the age of modern chemoradiation. Gynecologic Oncology 2011;121(1):131–134. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westin SN, Rallapalli V, Fellman B, et al. Overall survival after pelvic exenteration for gynecologic malignancy. Gynecologic oncology 2014;134(3):546–551. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baiocchi G, Guimaraes GC, Rosa Oliveira RA, et al. Prognostic factors in pelvic exenteration for gynecological malignancies. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO) 2012;38(10):948–954. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maggioni A, Roviglione G, Landoni F, et al. Pelvic exenteration: Ten-year experience at the European Institute of Oncology in Milan. Gynecologic Oncology 2009;114(1):64–68. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuo K, Mandelbaum RS, Adams CL, Roman LD, Wright JD. Performance and outcome of pelvic exenteration for gynecologic malignancies: A population-based study. Gynecologic Oncology 2019;153(2):368–375. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Overall survival by primary disease location