Abstract

Background:

HIV index testing, an intervention in which HIV-positive “indexes” (persons diagnosed with HIV) are supported to recruit their “contacts” (sexual partners and children) efficiently identifies HIV-infected persons in need of treatment and HIV-uninfected persons in need of prevention. However, index testing implementation in sub-Saharan African healthcare settings has been suboptimal. The objective of this study was to develop and pilot test a blended learning capacity-building package to improve index testing implementation in Malawi.

Methods:

In 2019, a blended learning package combining digital and face-to-face training modalities was field tested at six health facilities in Mulanje, Malawi using a pre-/post- type II hybrid design with implementation and effectiveness outcomes. Health care worker (HCW) fidelity to the intervention was assessed via observed encounters before and after the training. Preliminary effectiveness was examined by comparing index testing program indicators in the two months before and four months after the training. Indicators included the mean number of indexes screened, contacts elicited, and contacts who received HIV testing per facility per month.

Results:

On a 30-point scale, HCW fidelity to index testing protocols improved from 6.0 pre- to 25.5 post-package implementation (p=0.002). Index testing effectiveness indicators also increased: indexes screened (pre=63, post=101, p<0.001); contacts elicited (pre=75, post=131, p<0.001); and contacts who received HIV testing (pre=27, post=41, p=0.014).

Conclusion:

The blended learning package improved fidelity to index testing protocols and preliminary effectiveness outcomes. This package has the potential to enhance implementation of HIV index testing approaches, a necessary step for ending the HIV epidemic.

Keywords: HIV index testing, assisted partner notification, contact tracing, blended learning, digital learning, implementation science

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the highest burden of HIV globally. Despite great progress, approximately 20% of HIV-positive persons—4.9 million individuals—remain undiagnosed 1. Index testing, in which the sex partners and children of HIV-positive persons are notified of their exposure to HIV and offered testing, efficiently diagnose people living with HIV (PLHIV) and persons in need of HIV prevention 2-4. Offering assisted index-based options, also known as assisted partner notification (APN), in which health care workers (HCWs) support indexes with contact recruitment, are more effective than passive approaches, in which indexes recruit contacts on their own 5-8. Since its 2016 guidance, index testing that includes APN has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) 9.

In the ensuing years, index testing with APN options has been adopted as policy in many SSA countries, including Malawi. However, outcomes in routine program settings have been inferior to outcomes in trial settings 10. For example, in a Malawi-based trial of APN 6, it took two indexes to find one new HIV-positive contact, while in routine settings, 24 indexes were required to find one new HIV-positive contact 11. Innovative implementation strategies to support HCWs and enhance real-world effectiveness are needed.

Lessons learned from low and middle income countries (LMICs) demonstrate that HCW training along with continuous quality improvement are key ingredients for successful health worker capacity building 12. For index testing, in particular, effective capacity building has consisted of didactic instruction, modeled encounters, practice, and feedback 13. However, such activities are time-intensive, expensive, and as a result, unevenly applied.

In recent years, digital learning has proliferated in the health sector 14, including in Low and Middle Income Country (LMIC) contexts 15-20, due to many enticing features: 1) learning is not time- or place-dependent; 2) learning does not require an on-site instructor; 3) pace and degree of difficulty can be tailored; 4) progress and aptitude can be easily monitored; 5) content can be delivered consistently; and 6) infrastructure needs are minimal. Together, these features could potentially make this strategy ideal for improving training for index testing. The WHO supports digital training modalities that complement face-to-face trainings for HCWs in LMIC settings 21,22. These “blended learning” approaches combine the best features of digital learning (i.e. quality, consistency, and convenience) with the best features of face-to-face learning (i.e. group engagement, interactivity, and feedback) 23,24. However, they have not been formally assessed in LMICs for a range of implementation and effectiveness outcomes.

We sought to use blended learning to implement an effective index testing capacity building package. We evaluated the impact of this blended learning approach on fidelity to index testing protocols, HCW perceived effectiveness, and preliminary effectiveness (i.e. uptake of services). The long-term goal of this work is to bring routine index testing services to scale in Malawi and beyond.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Mulanje, Malawi, one of the most affected districts in Malawi, with an adult HIV prevalence of 20.6% 25. The facilities were operated through Malawi Ministry Of Health (MOH) or Christian Association of Malawi (CHAM), a faith-based organization implementing the MOH HIV program. At these facilities, HIV testing services and index testing programs were free and provided according to MOH guidelines 26,27. During the study period, the Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation Malawi Tingathe Program 28 supported the MOH and CHAM with service provision.

In March 2019, the index testing program evolved from passive referral to a choice-based APN approach 29. Choices included passive referral, provider referral, contract referral, and dual referral. Passive referral is when the index client is encouraged to disclose the exposure of their partner(s) to HIV by themselves and encourage them to go for testing. Contract referral occurs when a health care provider and index client agree to a specified amount of time in which the index should contact, notify and refer sexual partners. After the time elapses, if the contacts have not returned for testing, the health care provider informs the contact about their exposure while maintaining the anonymity of the index case. In provider referral, a health care provider contacts the partners directly, while maintaining confidentiality of the index client. In dual referral, the provider sits with the index and their contact as the index or provider discloses his or her HIV status and offers HTS to the partner 30. Through this program, HCWs are expected to identify index clients, introduce the index-counseling session, elicit all potential contacts, assess index safety, discuss options for recruiting each contact, and discuss the logistics of the options selected. Index testing is guided by the principles of voluntariness, client-centeredness, confidentiality, non-judgmental approaches, and culturally and linguistically appropriate exchanges.

The blended learning capacity-building package

In previous work, we developed and tested a face-to-face HCW capacity building package that was deployed at a central venue and led by a facilitator. It included didactic presentations, modeled counseling encounters, facilitated HCW role-plays, and feedback to HCWs. This set of activities was grounded in the Theory of Expertise 31 an educational theory suggesting that deliberate practice and a core set of activities (learning, observing, practicing, and receiving feedback) promote mastery of skills 32,33. In addition, there was action planning and ongoing problem solving within a continuous quality improvement framework to address implementation barriers and facilitators.

We hypothesized that using a digital delivery platform would make these strategies more scalable, reduce variability among trainers, and facilitate ongoing learning 17,34. We adopted a blended learning approach to enhance implementation of the capacity building package. The blended learning package was designed as a PowerPoint presentation with a pre-recorded narration, making an experienced trainer unnecessary. It consisted of didactic slides and embedded role-play videos, with experienced counselors demonstrating how to navigate through counseling scenarios. These role-plays modeled examples of good and poor quality counseling skills, followed by narrated debriefs. There were prompts throughout for participants to practice core skills in small groups with clearly specified objectives. The implementation package was designed to equip HCWs with counselling skills to be comfortable with identifying index clients, enhancing uptake and explaining index testing as a choice-based approach. In addition, action planning was introduced to facilitate problem solving and discuss implementation barriers and potential solutions.

Study design and procedures

We conducted a pre-/post- pilot assessment comparing the standard face-to-face capacity building package (pre) to the blended learning capacity building package (post). Prior to the pre-implementation period (August-September 2019), we conducted a two-day face-to-face training (June-July 2019) which was led by a facilitator. The assessment was conducted in six health facilities supported by the Tingathe program. At each facility, lay HCWs who provided index testing services were purposively selected. The blended learning package was administered as a Powerpoint presentation projected through a computer provided by Tingathe Program at a central venue accessible to all the pilot health centers. It was implemented in October, 2019 and thus we examined pre-implementation data from the two months prior (August-September 2019) and post-implementation data in the four months after (November 2019-February 2020). We used a hybrid Type II pilot study using a quasi-experimental design with implementation and effectiveness outcomes. We sought to assess a) HCW fidelity to index testing procedures (pre/post), b) HCW perceived effectiveness (post) and c) preliminary clinical effectiveness (pre/post).

Fidelity

Fidelity was defined as the degree to which the index testing intervention was implemented as it was intended, considering both adherence to core elements and quality 35. Adherence included introducing the session, eliciting all potential contacts, assessing index safety, discussing options for recruiting each contact, helping the indexes select an appropriate contact method, discussing the logistics of the methods selected, and summarizing the action points. Quality was the extent to which the counseling was voluntary, client-centered, confidential, non-judgmental, and culturally and linguistically appropriate.

Assessments were conducted through observed simulations of standardized client encounters by actors portraying index clients using a consistent set of scenarios. Research staff observed each HCW on how they counseled the index client actor once before and once after implementation of the blended learning package.

Fidelity was assessed using a 15-item instrument. A grading criteria was developed and, research staff were rigorously trained on these criteria to ensure they were performing consistently prior to the pilot. Following the observation, the research staff provided a score of poor (0), good (1), or excellent (2) for a potential total score of 30-points. Fidelity data were recorded on paper forms by research staff and entered in Excel with field checks for validity, cross-checked with the paper forms to ensure correct data entry and exported into STATA version 13.0 for cleaning and analysis. Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests were conducted to compare median scores pre- and post-.

Perceived effectiveness

We defined perceived effectiveness as the perception among HCWs that the blended learning package was impactful to them 36. All HCWs completed a perceived effectiveness assessment immediately following participation in the blended learning activities (post only). It was assessed using a 10-item survey that listed statements about different aspects of the blended learning capacity building package on a 4-point Likert scale of agreement. These statements assessed the images, text, and narration; video role-plays; practice role plays; group discussions; and feedback from the facilitator. These data were collected through paper forms and entered in an Excel file with field checks for validity, cross-checked with the paper forms, and exported into STATA version 13.0 for cleaning and analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated.

Preliminary Effectiveness

Preliminary effectiveness was evaluated by comparing pre- and post-routine index testing outcomes. Indicators included the number of index clients identified, the number of contacts elicited, the number of contacts tested. Additionally, we examined the proportion of index clients choosing assisted, rather than passive, referral approaches. Monthly facility-level aggregate data were abstracted from the Tingathe Program Index Testing Register and entered into an Excel database and exported to STATA version 13.0 for cleaning and analysis. No individual-level data were used.

The dataset had one observation per facility per month over six months: 12 records pre- and 24 records post. Paired t-tests (matched at facility level) were used to compare means of indicators pre- and post-. Poisson regression with an offset term, which models rates, rather than simple counts, were used to estimate rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals37. Unadjusted and adjusted Poisson regression models were implemented using generalized estimating equations to account for correlation by facility. Models used a log link and an offset term to account for total number of tests conducted in each month. Models were also adjusted for facility type (MOH or CHAM) and facility level (tertiary hospital or health centre). We reported incidence rate ratios and ninety-five percent confidence intervals comparing all programmatic indicators pre- and post-implementation.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the National Health Sciences Research Committee, the local ethics committee in Malawi and the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all HCWs.

Results

Population

The blended learning package was pilot tested in six facilities in Mulanje: five facilities were operated by the MOH and one by CHAM. Five facilities were health centres and one was a secondary-level hospital. Among the 12 HCWs trained, four were female. Median age was 31.5 years (range 20-42). Five were Community Health Workers and seven were HIV Diagnostic Assistants. Three had some secondary school education, seven completed secondary school, and two had tertiary education. All were employed by Tingathe Program.

Fidelity

Each HCW was observed once before and once after exposure to the blended learning package. Fidelity increased from a median of 6.0 pre- (range 1-19) to 25.5 post- (range 11-29) out of 30 possible points (p=0.002) (Table 1). Fidelity improvements were observed across all 15 assessment items and among all HCWs.

Table 1:

Comparing medians of fidelity scores before and after the blended learning training

| Fidelity assessment item | Median (range) pre |

Median (range) post |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session introduced | 0 (0-2) | 2 (1-2) | 0.016 |

| Biologic children discussed | 1 (0-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.006 |

| Sexual partners discussed | 1 (0-1) | 1 (1-2) | 0.009 |

| Other household members discussed | 0 (0-1) | 1.5 (1-2) | 0.002 |

| Index safety assessed | 1 (0-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.004 |

| Contacts recruitment methods described | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 0.033 |

| Contact recruitment method selected | 0 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 0.006 |

| Logistics discussed | 0 (0-2) | 1.5 (0-2) | 0.009 |

| Discussion summarized | 0 (0-2) | 1.5 (0-2) | 0.006 |

| Voluntariness respected | 0.5 (0-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.002 |

| Client-centeredness respected | 0 (0-1) | 2 (0-2) | 0.002 |

| Confidentiality discussed | 0 (0-2) | 2 (1-2) | 0.002 |

| Non-judgmental attitudes conveyed | 1 (1-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.002 |

| Conducted with cultural and linguistic appropriateness | 1 (0-1) | 2 (0-2) | 0.004 |

| Session contained natural order and flow | 1 (0-1) | 2 (0-2) | 0.004 |

| Overall fidelity | 6.0 (1-19) | 25.5 (11-29) | 0.002 |

Perceived effectiveness

HCWs who participated in the pilot training considered the blended learning package to be effective. For all 10 items, all participants agreed or strongly agreed with each statement; no participants disagreed or strongly disagreed with any statement. A majority of participants strongly agreed that didactic elements, role-play videos, practice sessions, feedback, and group discussions improved their ability to counsel index clients. Overall, 75% strongly agreed that they would recommend this training style in the future (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Health care workers perceived effectiveness of the blended learning training

Preliminary effectiveness

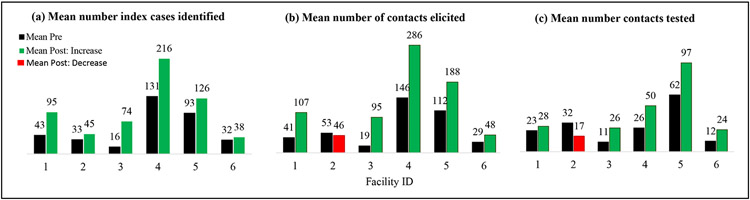

In the months following blended learning package implementation, the mean number of index cases per facility per month increased (pre=63.3, post=100.7, p<0.001). This trend was observed in all six facilities (Figure 2). The mean number of indexes identified per facility per month was 1.7 times higher in the post-period compared to the pre-period (Table 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Index case identified, (b) Contacts elicited and (c) Contacts tested per facility per month pre and post-implementation package

Table 2:

Comparison of key indicators pre and post the implementation package

| Data source | Mean pre |

Mean post |

p-value | Unadjusted Poisson Regression |

Adjusted Poisson Regression* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index Case Testing register | |||||||

| Index cases identified | 63.29 | 100.74 | <0.001 | 1.71 | (1.36-2.17) | 1.68 | (1.31-2.17) |

| Total contacts elicited | 75.14 | 131.26 | <0.001 | 1.92 | (1.50-2.49) | 1.88 | (1.44-2.46) |

| <1 year | 0 | 0.52 | 0.158 | (non-convergence) | |||

| 1 to 14 years | 37.29 | 65.13 | 0.004 | 2.07 | (1.47-2.92) | 1.99 | (1.41-2.81) |

| 15 to 24 years | 6.29 | 15.04 | <0.001 | 2.18 | (1.51-3.15) | 2.17 | (1.59-2.96) |

| ≥25 years | 31.43 | 49.17 | 0.001 | 1.68 | (1.19-2.56) | 1.64 | (1.12-2.40) |

| Sexual partners | 32.86 | 55.35 | <0.001 | 1.81 | (1.27-2.58) | 1.77 | (1.20-2.62) |

| Biological children | 40.43 | 71.13 | 0.003 | 1.98 | (1.41-2.78) | 1.90 | (1.36-2.67) |

| Guardians/other | 1.86 | 3.43 | 0.473 | 2.32 | (0.73-7.36) | 2.21 | (0.78-6.31) |

| Total contacts tested | 27.42 | 40.71 | 0.014 | 1.73 | (1.17-2.56) | 1.56 | (1.10-2.22) |

| Total contacts new HIV+ | 4.00 | 7.50 | 0.409 | 2.65 | (1.18-5.93) | 2.29 | (1.18-4.46) |

Models were adjusted for facility type and level of care

The mean number of contacts elicited per facility per month also increased (pre=75.1, post=131.3, p<0.001). Based on descriptive analysis, this trend was observed in five of the six facilities (Figure 2). The mean number of contacts identified per facility per month was 1.9 times higher in the post-period compared to the pre-period. When disaggregated by age, an increase in the mean number of contacts was not observed among those <1 year, but was observed among those 1-14 years, 15-24 years, and >25 years. There was an increase in the mean number of sexual partners and biological children, but not guardians (Table 2).

The mean number of contacts tested per facility per month also increased (pre=27.4, post=40.7, p=0.014). This trend was observed in five of the six facilities (Figure 2). The mean number of contacts tested per facility per month was 1.6 times higher in the post-period compared to the pre-period. There was a trend towards more contacts newly testing as HIV-positive per facility per month, but the analysis was not powered to observe a statistical difference (pre=4.0, post=7.5, p=0.409). The mean number of HIV-positive persons identified was 2.3 times higher in the post-period compared to the pre-period (Table 2).

One additional indicator improved post-implementation: the proportion of index clients selecting APN approaches as compared to those choosing passive referral approaches per facility per month (pre=88%, post=95%, p=0.002).

Discussion

We developed and pilot-tested a blended learning capacity-building package to support scale-up of index testing in Malawi with promising early results. The package improved HCW’s fidelity to counseling protocols, was perceived to be highly effective by HCWs, and improved a number of meaningful clinical indicators, including indexes counseled, contacts elicited, and contacts who reported for HIV testing. Furthermore, it supported more clients to select assisted, rather than passive methods.

Translating effective interventions from trials to routine health settings requires effective implementation strategies, supported by rigorous implementation science. In the years since the WHO issued guidelines surrounding assisted partner notification, there has been widespread implementation 10,38. However, well-designed evaluations of different implementation strategies are lacking, an important unmet need. This study is the first to evaluate index testing implementation strategies using a Type II pre/post study design, which allows for inferences about both implementation and effectiveness outcomes.

Our study offers important insights into rapidly improving the fidelity of an HIV counseling intervention in an SSA setting. Fidelity scores improved dramatically and HCWs reported that each element of the training (learning, modeling, practicing, and receiving feedback) improved their perceived ability to implement the intervention. These findings support the Theory of Expertise 31, suggesting that this set of activities can be successfully delivered with a blended learning framework.

In the months following package implementation, we saw improvements in clinical outcomes, with increases in the number of indexes counseled, contacts elicited, and contacts who reported for testing. The package also resulted in more index clients choosing assisted approaches, which have been shown to increase the number of contacts reporting for testing, compared with passive approaches 5. Similar to lay health workers capacity-building interventions in other LMIC settings, we observed that the combination of training and group problem-solving led to improved programmatic outcomes 12. Although there has been a proliferation of digital and blended learning tools for LMICs over the last decade, most evaluations have focused on proximal outcomes, such as adoption, HCW knowledge, and skills. The WHO highlighted the critical need for research assessing the impact of blended learning on HCW practices and patient outcomes in LMIC settings 22. Our study directly addresses this set of research needs, an important contribution to digital learning.

Our approach falls within the blended learning paradigm. These approaches are often more effective than either electronic or face-to-face learning alone for acquiring new knowledge and skills, and are promising modalities for improving HCW counseling and communication 14,39,40. The promising preliminary results observed in this study demonstrate that this type of approach can be extended to lay HCWs in LMIC settings. This study was conducted prior to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic and ensuing recommendations for physical distancing, which have made large in-person trainings risky. As such, these blended learning approaches could be ideal for a range of remote training needs which are now more essential than ever.

There are some important limitations in our study. First, we observed simulated encounters to evaluate fidelity, rather than actual encounters. Future studies should consider observing actual index testing counseling sessions. Video recordings of these sessions could mitigate the potential Hawthorne effect on the assessment of HCWs’ performance 41. Second, lack of individual-level client data limited our ability to account for client-level factors that may have influenced the clinical outcomes observed. Third, secular trends may partially account for the improvements observed among the index case testing indicators. The pilot study demonstrated preliminary effectiveness of the package, but we plan to evaluate this training further in a cluster randomized controlled trial with more facilities over a longer period of time. Next, we are unable to determine whether there are certain key parts of the package that were responsible for these improvements. Finally, we were not able to assess sustainment beyond the four month period observed or how frequently the package should be delivered. Future research is required to better understand these important dimensions of our research questions.

Index testing is a targeted approach for effectively identifying HIV-positive persons in need of treatment and HIV-uninfected persons in need of HIV prevention services. Our evaluation of a blended learning capacity-building package offers a promising approach for bringing these effective approaches to scale, and ultimately supporting ambitious global HIV testing, treatment and prevention goals, key steps to ending the HIV epidemic.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge and thank the Malawi Ministry of Health, Tingathe Outreach Programme Team, Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation Malawi, Baylor International Pediatric AIDS Initiative, The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Source of Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW010060 and R01 MH124526-01. Maria H. Kim was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award number K01 TW009644 and R01 MH115793-04. Nora E. Rosenberg is supported by the National Institutes of Health through R01 MH124526-01 and R00 MH104154.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Joint_United_Nations_Programme_on_HIV/AIDS_(UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahabuka C, Plotkin M, Christensen A, et al. Addressing the First 90: A Highly Effective Partner Notification Approach Reaches Previously Undiagnosed Sexual Partners in Tanzania. AIDS and behavior. 2017;21(8):2551–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henley C, Forgwei G, Welty T, et al. Scale-up and case-finding effectiveness of an HIV partner services program in Cameroon: an innovative HIV prevention intervention for developing countries. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(12):909–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528(7580):S77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown LB, Miller WC, Kamanga G, et al. HIV partner notification is effective and feasible in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for HIV treatment and prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(5):437–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg NE, Mtande TK, Saidi F, et al. Recruiting male partners for couple HIV testing and counselling in Malawi's option B+ programme: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. The lancet HIV. 2015;2(11):e483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherutich P, Golden MR, Wamuti B, et al. Assisted partner services for HIV in Kenya: a cluster randomised controlled trial. The lancet HIV. 2017;4(2):e74–e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal S, Johnson C, Fonner V, et al. Improving HIV test uptake and case finding with assisted partner notification services. AIDS. 2017;31(13):1867–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing guidelines. 2016. [PubMed]

- 10.Lasry A, Medley A, Behel S, et al. Scaling Up Testing for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Among Contacts of Index Patients - 20 Countries, 2016-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(21):474–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tingathe Program Data. Lilongwe: Baylor College of Medicine Children's Foundation; 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe A, Rowe S, Peters D, Holloway K, Chalker J, Ross-Degnan D. Effectiveness of strategies to improve health-care provider practices in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health. 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han H, Myers S, Mboh Khan E, et al. Assisted HIV partner services training in three sub-Saharan African countries: facilitators and barriers to sustainable approaches. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019;22 Suppl 3:e25307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q, Peng W, Zhang F, Hu R, Li Y, Yan W. The Effectiveness of Blended Learning in Health Professions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of medical Internet research. 2016;18(1):e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal S, Perry HB, Long LA, Labrique AB. Evidence on feasibility and effective use of mHealth strategies by frontline health workers in developing countries: systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2015;20(8):1003–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long LA, Pariyo G, Kallander K. Digital Technologies for Health Workforce Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Global health, science and practice. 2018;6(Suppl 1):S41–S48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winters N, Langer L, Nduku P, et al. Using mobile technologies to support the training of community health workers in low-income and middle-income countries: mapping the evidence. BMJ global health. 2019;4(4):e001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallander K, Tibenderana JK, Akpogheneta OJ, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) approaches and lessons for increased performance and retention of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: a review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2013;15(1):e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shorbaji N, Atun R, Car J, Majeed A, Wheeler E. e-Learning for undergraduate health professional education: A systematic review informing a radical transformation of health workforce development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun R, Catalani C, Wimbush J, Israelski D. Community health workers and mobile technology: a systematic review of the literature. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e65772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cometto G, Ford N, Pfaffman-Zambruni J, et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. The Lancet Global health. 2018;6(12):e1397–e1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World_Health_Organization. WHO Guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva: World Health Oranization 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathews C, Guttmacher SJ, Coetzee N, et al. Evaluation of a video based health education strategy to improve sexually transmitted disease partner notification in South Africa. Sexually transmitted infections. 2002;78(1):53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiasson MA, Shaw FS, Humberstone M, Hirshfield S, Hartel D. Increased HIV disclosure three months after an online video intervention for men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS care. 2009;21(9):1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015-16. Zomba, Malawi and Rockville, Maryland USA: National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malawi HIV Testing Services Guidelines. Lilongwe, Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults. Lilongwe, Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MH, Ahmed S, Buck WC, et al. The Tingathe programme: a pilot intervention using community health workers to create a continuum of care in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cascade of services in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15 Suppl 2:17389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward H, Bell G. Partner notification. Medicine (Abingdon). 2014;42(6):314–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreira A, Young T, Mathews C, Zunza M, Low N. Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(10):Cd002843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008;15(11):988–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Medical teacher. 2005;27(1):10–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taras J, Everett T. Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice in Medical Education - a Systematic Review. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donovan J, O'Donovan C, Kuhn I, Sachs SE, Winters N. Ongoing training of community health workers in low-income andmiddle-income countries: a systematic scoping review of the literature. BMJ open. 2018;8(4):e021467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and policy in mental health. 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suka M, Yamauchi T, Yanagisawa H. Perceived effectiveness rating scales applied to insomnia help-seeking messages for middle-aged Japanese people: a validity and reliability study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2017;22(1):69–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hilbe JM. Negative Binomial Regression. Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz DA, Wong VJ, Medley AM, et al. The power of partners: positively engaging networks of people with HIV in testing, treatment and prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 3(Suppl Suppl 3):e25314–e25314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martino S Strategies for training counselors in evidence-based treatments. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2010;5(2):30–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Funes R, Hausman V, Rastegar A. Preparing the next generation of community health workers: The power of technology for training Dalberg Global Development Advisors; May 2012. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies DR, & Shackleton VJ Psychology and Work. London: Methuen; 1975. [Google Scholar]