Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine if plasma cyclohexanone and metabolites are associated with clinical outcomes of children on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. We performed a secondary analysis of a prospective observational study of children on ECMO support at two academic centers between July 2010 and June 2015. We measured plasma cyclohexanone and metabolites on the first and last days of ECMO support. Unfavorable outcome was defined as in-hospital death or discharge Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category score >2 or decline ≥1 from baseline. Among 90 children included, 49 (54%) had unfavorable outcome at discharge. Cyclohexanediol, a cyclohexanone metabolite, was detected in all samples and at both time points; concentrations on the first ECMO day were significantly higher in those with unfavorable vs favorable outcome at hospital discharge (median 5.7 ng/μL, interquartile range [IQR], 3.3–10.6 ng/μL vs median, 4.2 ng/μL, IQR, 1.7–7.3 ng/μL; p=0.04). Two-fold higher cyclohexanediol concentrations on the first ECMO day were associated with increased risk of unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge (multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.24 [95%CI, 1.05–1.48]). Higher cyclohexanediol concentrations on the first ECMO day were not significantly associated with new abnormal neuroimaging or one-year Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-II score <85 or death among survivors.

Keywords: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO, cyclohexanone, child

INTRODUCTION

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is used in more than 3,600 children with severe, refractory, cardiopulmonary failure yearly.1 While lifesaving, ECMO remains a high-risk procedure, with adverse events affecting vital organs reported frequently.2 Children who survive critical illness with ECMO have been shown to suffer from short- and long-term neurofunctional deficits including cognitive, behavioral, and motor impairments, as well as decreased health-related quality of life compared to other critically ill peers and to normal controls.3–6 These deficits have been described even in the absence of known neurologic complications such as ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage.3

Cyclohexanone is an organic solvent sealer used in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) medical devices, including intravenous fluid bags, tubing and stopcocks, and cardiopulmonary bypass, dialysis and ECMO circuits.7–11 In animals, cyclohexanone leads to decreased neural cell viability and abnormal neurological manifestations such as central nervous system depression, stupor, hyper or hypoactivity, ataxia, and convulsive movements.12–14 Human neurotoxicity has also been documented, primarily through occupational exposure15,16 and in settings that are dramatically different from the potential acute intravenous exposure in hospitalized infants and children. Human neurotoxicity data are limited to workers with consistent daily exposure over many years through inhalation and skin contact, with no human data from oral or intravenous exposure available.15,16 Given the high degree of exposure of ECMO patients’ blood to medical device surfaces, we hypothesized that patients supported on ECMO are exposed to cyclohexanone leaching into the extracorporeal blood stream. We further hypothesized that this exposure is commensurate to the patient’s total blood volume – to – extracorporeal circuit volume ratio, and that exposure to cyclohexanone is associated with short- and long-term mortality and neuropsychologic deficits. The goals of this study were to characterize plasma levels of cyclohexanone and its metabolites in children on ECMO, and to determine if cyclohexanone and metabolite levels are associated with clinical outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This prospective observational cohort comprised children supported on ECMO at two academic, quaternary care, urban, pediatric intensive care units between July 2010 and June 2015. Characteristics of the cohort have been previously published.17 Informed consent was obtained within 24 hours of ECMO cannulation, with blood samples collected daily during the ECMO course. Detailed neuroimaging data during the hospitalization, as well as short- and long-term neuropsychologic outcomes were collected as part of the parent study. Banked plasma was used for this study from subjects who consented for future use of samples for ECMO-related studies. Hospital and ECMO care were provided according to each institution’s standard of clinical care during the study period. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating centers.

The ECMO circuits during the study period consisted of custom-packed 1/4- or 3/8-inch flexible PVC tubing (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) with a silicone reservoir, a bladderbox (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD), a 0.8 m2 to 4.5 m2 membrane oxygenator (Medtronic), a heat exchanger (Medtronic), and a roller pump (Sorin Cardiovascular USA, Arvada, CO) up to January 2011, and the Better Bladder (Coastal Life Systems Inc, San Antonio, TX), the Quadrox-ID oxygenator (Maquet Cardiopulmonary, Rastatt, Germany), and a roller pump (for infants <10 kg) or centrifugal pump (for children ≥10 kg) (Sorin), thereafter, at one site. At the other site, the ECMO circuit consisted of custom-packed 1/4- or 3/8-inch flexible PVC tubing (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), the Better Bladder (Coastal Life Systems Inc), the Quadrox-ID oxygenator (Maquet Cardiopulmonary), and a centrifugal pump (Medtronic). During the study period, both centers used unfractionated heparin infusion for anticoagulation. Anticoagulation management was primarily driven by activated clotting time (goal 180–220 seconds), with anti-factor Xa and antithrombin activity measured as needed for concerns for heparin resistance or excessive bleeding or clotting.

Cyclohexanone and metabolites

This analysis used plasma samples obtained within the first and last 24 hours of ECMO support. All samples had been stored at –80ºC. Samples were analyzed for concentrations of cyclohexanone and its metabolites by mass spectrometry, as described in detail in the Supplemental Digital Content (Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Table 1). Cyclohexanone metabolites were measured as 1,2-cyclohexanediol (cis and trans) and 1,4-cyclohexanediol (cis and trans). Since there was no previously published literature to suggest differential health effects between cis and trans configuration isomers, we summed 1,2-cyclohexanediol and 1,4-cyclohexanediol by the respective cis and trans concentrations. In addition, we compared the within-sample relationship between 1,2-cyclohexanediol and 1,4-cyclohexanediol by agreement plots.

Statistical analyses

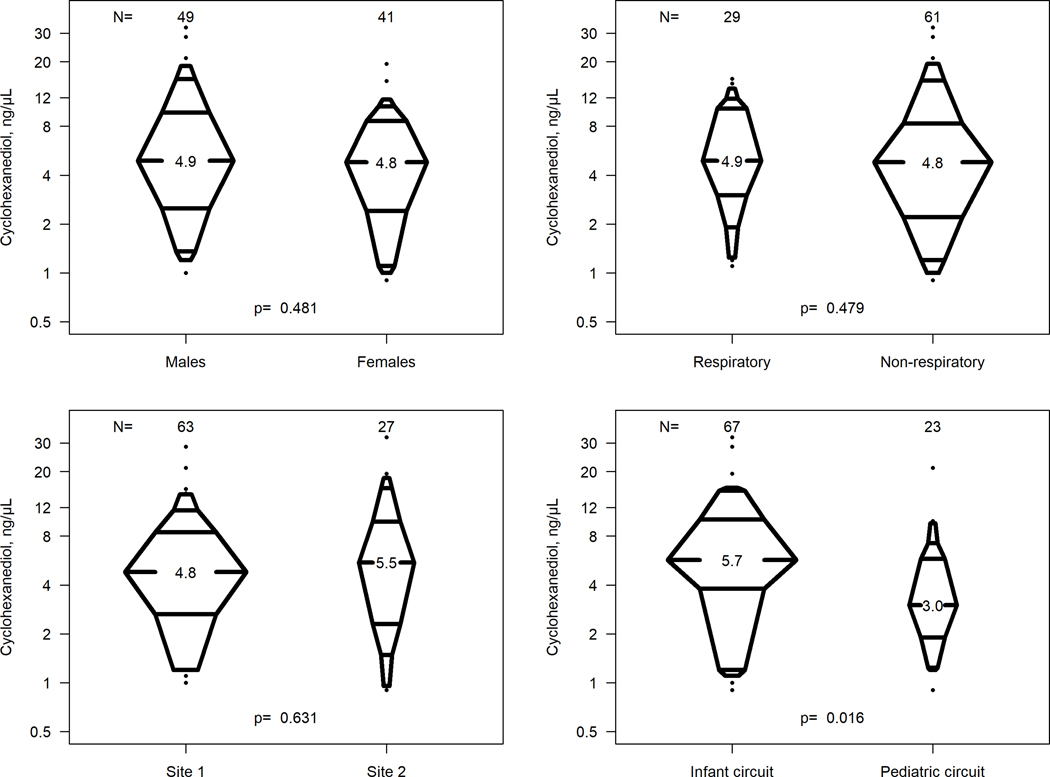

We first characterized putative differences in ECMO day 1 cyclohexanone metabolites by age (neonate vs age ≥ 30 days), sex, primary indication for ECMO (respiratory vs non-respiratory), study site, and circuit type. During the study period, “infant” circuits were utilized for infants ≤ 10 kg and ≤ 15 kg at Site 1 and Site 2, respectively; the complement were larger “pediatric” circuits. We characterized the distribution of cyclohexanediol concentrations in the log scale by enhanced percentile boxplots, stratified by these variables.

We then examined the association between the ECMO day 1 cyclohexanone metabolite concentrations and time to in-hospital death or discharge with unfavorable Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category18,19 (defined as discharge PCPC >2 and decline ≥1 point from baseline PCPC), as well as time to abnormal neuroimaging. Neuroimaging studies included head ultrasound (pre-ECMO and daily during the ECMO course), brain computed tomography (CT) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), all obtained by the treating team as part of institutional clinical protocols. The date, time, and type of new neuroimaging abnormality (new ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, or asphyxial injury) were recorded for all neuroimaging studies available during ECMO support and up to 6 weeks after decannulation.

The independent variable was log base 2-transformed cyclohexanone metabolite level on ECMO day 1 and the dependent variables were time to unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge and time to abnormal neuroimaging after ECMO cannulation in a Cox proportional hazards model. Cox proportional hazards models were both unadjusted and adjusted for the variables used in the first analysis (age, sex, ECMO indication, study site, and circuit type).

The final analysis was restricted to those who survived to hospital discharge. Conditional on survival to discharge, we estimated the association of a two-fold higher ECMO day 1 cyclohexanone metabolite levels and the odds of Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-II (VABS-II) score < 85 (i.e., one standard deviation below the reference population mean) or death up to 1 year after ECMO decannulation.17

RESULTS

The parent cohort included 99 critically ill children supported on ECMO; of these, 7 did not have banked plasma samples available for measurement (one of 7 died before hospital discharge), and 2 had outlying cyclohexanediol measurements (close to 0) and were excluded from the main analysis (one died, and one survived to hospital discharge).

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of children included in this study (n=90). In summary, 54% were male, 47% were <30 days of age, and the median weight was 4.0 kg (interquartile range [IQR], 3.1–12 kg). About one third of children had a primary respiratory ECMO indication (32%) and 74% were supported with an infant circuit. The median duration of ECMO was 4.8 days (IQR, 3.2–9 days). Eighty (89%) children had neuroimaging during ECMO or within 6 weeks from ECMO decannulation. Forty of 80 (50%) children with neuroimaging displayed imaging abnormalities. A total of 49 children (54%) had unfavorable short-term outcome at hospital discharge (40 died before discharge and 9 were discharged alive with unfavorable PCPC). Of the 50 children who survived to discharge, 37 were seen in follow-up, and 15 (30%) had unfavorable long-term outcomes: death (n=3) or VABS-II score <85 (n=12) at six to twelve months after hospital discharge.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Population for Study of Cyclohexanone Metabolite Concentrations and Neurologic Outcomes after Pediatric ECMOa

| Variable | All (n= 90) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Male | 49 (54) |

| Age group | |

| Neonate (<30 days) | 42 (47) |

| Infant (≥30 days to < 1 year) | 22 (24) |

| Child (≥1 year to <12 years) | 18 (20) |

| Adolescent (≥ 12 years) | 8 (9) |

| Weight, kg | 4.0 [3.1, 12.0] |

|

| |

| ECMO characteristics | |

| Primary indication for ECMO | |

| Respiratory failure | 29 (32) |

| Non-respiratory (cardiac failure, ECPR, sepsis) | 61 (68) |

| Infant circuit | 67 (74) |

| ECMO duration, days | 4.8 [3.2, 9.0] |

|

| |

| Outcomes | |

| Abnormal neuroimaging, n=80 available imaging studies | 40 (50) |

| Unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge, n=90 | 49 (54) |

| In-hospital mortality | 40 (44) |

| Discharge PCPC>2 or decline ≥1 from baseline PCPC | 9 (10) |

| Unfavorable long-term outcomes, n=50 survivors to hospital discharge | |

| VABS-II score <85 or death | 15 (30) |

| Unknown functional outcome | 13 (26) |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VABS-II, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition

Categorical variables are presented as counts (frequencies) and continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges.

On ECMO day 1, only 12 children (13%) had detectable levels of cyclohexanone, ranging from 0.1 to 0.2 ng/μL. In contrast, all samples had detectable levels of cyclohexanone metabolites: 1,2-cyclohexanediol and 1,4-cyclohexanediol. The correlation between the two metabolites was high (≥0.920), with 1,2-cyclohexanediol systematically higher than 1,4-cyclohexanediol (Figure 1). Since the relationships were linear (in log scale) with strong correlation and there are no known differential effects related to metabolites, we calculated total cyclohexanediol concentrations as the sum of 1,2- and 1,4-cyclohexanediol within each sample. The median cyclohexanediol concentrations were 4.9 ng/μL (IQR, 2.4–9.4 ng/μL) and 6.4 ng/μL (IQR, 3.6–12.3 ng/μL) for the first and last day of ECMO support, respectively. The timing of the last ECMO day sample represented a surrogate for clinical decision for readiness to decannulate, which varied based on response to medical therapies and organ recovery. Therefore, all subsequent analyses were conducted using the baseline, or first ECMO day, cyclohexanediol concentrations.

Figure 1.

Relationship Between 1,2-cyclohexanediol and 1,4-cyclohexanediol Concentrations for Samples Obtained on the First (Panel A) and Last (Panel B) ECMO Day (n=90)

There were no statistical differences in cyclohexanediol levels on ECMO day 1 by sex (p=0.481), ECMO indication (p=0.479) or study site (p=0.631). In contrast, those supported with an infant circuit had significantly higher cyclohexanone metabolite concentrations compared to those supported with a pediatric circuit (median, 5.7 vs 3.1 ng/μL, p=0.016) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Cyclohexanediol Concentrations on ECMO Day 1 (n=90)

p-values are based on Wilcoxon rank sum test for differences between two groups.

Cyclohexanediol concentrations were higher on ECMO day 1 in those with unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge compared to those with favorable outcome (median 5.7 ng/μL, IQR, 3.3–10.6 ng/μL vs median, 4.2 ng/μL, IQR, 1.7–7.3 ng/μL; p=0.04). Figure 3A and Supplemental Table 2 present HRs from univariate, bivariate and multivariate Cox models for unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge. A two-fold higher cyclohexanediol concentration on ECMO day 1 was significantly associated with unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge (unadjusted HR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.04–1.47; adjusted HR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.05–1.48).

Figure 3.

Association of a Two-fold Higher Cyclohexanediol Concentration on ECMO Day 1 with Unfavorable Outcomes at Hospital Discharge (Panel A, n=90), Abnormal Neuroimaging (Panel B, n=80), and Unfavorable Long-term Outcomes Among Survivors to Hospital Discharge (Panel C, n=37)

Panel A and Panel B: hazard ratios calculated using Cox survival models

Panel C: odds ratios calculated using logistic regression models

Figure 3B and Supplemental Table 3 present HRs from Cox models for abnormal neuroimaging. In a univariate model, a two-fold higher cyclohexanediol level on ECMO day 1 was significantly associated with a 18% lower hazard of abnormal neuroimaging (HR, 0.82; 95%CI, 0.69–0.96). After adjusting for all five potential confounders, the association was not statistically significant (HR, 0.86; 95%CI, 0.72–1.02).

The HR for unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge associated with a two-fold higher cyclohexanediol on ECMO day 1 was 1.35 (95%CI, 1.12–1.62), after adjusting for neuroimaging status (normal, abnormal, and no neuroimaging obtained by treating team). After adjusting for cyclohexanediol concentration on ECMO day 1, the HR for unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge was 2.36 (95%CI, 1.27–4.41) for those with abnormal vs normal neuroimaging, and 1.63 (95%CI, 0.45–5.95) for those with no neuroimaging compared to normal neuroimaging.

We next compared cyclohexanediol concentrations among survivors to hospital discharge, stratified by long-term outcome. The ECMO day 1 cyclohexanediol levels were higher in those with unfavorable outcome at six to twelve months after discharge compared to those with favorable outcome (median, 4.9 ng/μL; IQR, 4.2–9.4 ng/μL vs median, 2.9 ng/μL; IQR, 1.2–6.7 ng/μL; p=0.046). There were 13 additional survivors for whom long-term follow-up data were not available, and the median cyclohexanediol concentration for this group was 4.7 ng/μL (IQR, 2.2–7.3 ng/μL). Figure 3C and Supplemental Table 4 present logistic regression models restricted to survivors to hospital discharge and measured outcomes up to one year post-ECMO (n=37). Odds ratios indicated elevated risk of unfavorable long-term outcomes associated with a two-fold higher cyclohexanediol level on ECMO day 1, but this association was not statistically significant (unadjusted OR, 1.48; 95%CI, 0.99–2.22; adjusted OR, 1.53; 95%CI, 0.95–2.46).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis including the two subjects with outlier (low) cyclohexanediol levels. The inferences and statistical significance of elevated risk of unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge associated with a two-fold higher cyclohexanediol levels on ECMO day 1 remained unchanged (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Lastly, we compared cyclohexanediol concentrations in the 3 subjects enrolled prior to the end of January 2011 (all of whom were neonates) and supported with circuits containing no-longer used equipment (i.e., silicone oxygenators) to the neonatal enrollees after January 2011. The geometric mean cyclohexanediol concentration across all measurements among neonates was 6.56 ng/μL. Among those on ECMO in 2010-January 2011, geometric mean cyclohexanediol concentration was 7.27 ng/μL, versus a mean of 6.52 ng/μL for those who initiated ECMO after January 2011 (p=0.549 from a linear regression using generalized estimating equations to account for the repeated measurements). When evaluating the ECMO day 1 vs last ECMO day, there was a significant difference in cyclohexanediol concentration by equipment period for the first sample (7.39 ng/μL vs 5.31 ng/μL, p=0.045). There was no difference between concentrations in the last ECMO day sample (7.07 ng/μL vs 8.25 ng/μL, p=0.836).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that critically ill infants and children have consistently detectable cyclohexanone metabolites in plasma samples drawn during the first and last ECMO days. These results were consistent across two ECMO centers that used ECMO circuits and disposable components from various manufacturing sources. Plasma concentrations of cyclohexanone metabolites were higher in infants compared to older children, which we hypothesized was related to higher ECMO circuit volume–to–patient blood volume ratio and thus higher exposure. Importantly, this analysis showed that higher cyclohexanone metabolite levels on the first ECMO day were independently associated with unfavorable outcomes at hospital discharge. No independent association was found between these levels and abnormal neuroimaging or outcomes at one year after ECMO.

Cyclohexanone is an organic solvent used broadly in manufacturing processes for various consumer products, including as a sealer in PVC-containing medical devices.7,9,10,20–23 Toxicity of cyclohexanone has been demonstrated in multiple animal species, following inhalation, ingestion, contact, intravenous or intraperitoneal exposure.12–14,24 Acute effects include lacrimation, salivation, respiratory depression, stupor, ataxia, hyper- or hypokinesia, cardiovascular dysfunction and edema formation.12–14,24 For intravenous exposure, Martis et al showed that both injection rate and cyclohexanone concentration were important determinants of acute toxicologic responses.14 In humans, toxicity data originate primarily from occupational settings, with inhalation, ingestion, skin or eye contact as exposure routes.15,25 Symptoms include eye and skin irritation, dermatitis, respiratory system irritation, and central nervous system effects ranging from drowsiness to narcosis and coma.15

Intravenous exposure to cyclohexanone in the medical setting has been of concern for at least three decades. In in vitro studies, cyclohexanone has been detected in multiple solutions from intravenous fluid administration sets, dialysis, cardiopulmonary bypass, and ECMO circuits and across different manufacturers.7–10,24 The amount leaching from individual sets can differ significantly based on sampling site and size of device7,9,10,22 and does not appear to be related to the solvent used (e.g., water vs other solutions such as 0.9% sodium chloride).7 Cyclohexanone was detected at bag base joints,9 with higher concentrations in smaller-volume bags and fluid administration sets.8,11 Indirect evidence for fluid administration sets as cyclohexanone sources was presented in a recent study of air samples collected from unoccupied neonatal incubators where medical equipment was added sequentially.20 Cyclohexanone was detected in all incubator air samples, with intravenous fluid administration sets contributing 89% of emissions.20

Once absorbed, cyclohexanone is metabolized in the liver and excreted renally.14,21,26,27 In in vivo human studies, cyclohexanone metabolites can be measured in plasma or urine. Measurements of urinary 1,2-cyclohexanediol and cyclohexanol are recommended in exposed workers.25,27 In the medical setting, Mills and Walker published findings from 278 newborn babies in a special care unit and reported presence of 1,2-, 1,3-, and 1,4-cyclohexanediol isomers in 101 of 584 urine samples analyzed.21 Cyclohexanone was found in intravenous dextrose and parenteral feeding solutions used in the unit.21 Of note, our finding of higher plasma concentrations of 1,2-cyclohexanediol compared to 1,4-cyclohexanediol in the ECMO population is consistent with similar proportions of the two metabolites described in urine in the Mills and Walker study.21

This year, our group also reported the presence of cyclohexanone and of 1,2-, 1,3-, and 1,4-cyclohexanediol in the serum of 85 neonates who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass surgery.28 Cyclohexanone and its metabolites were present in serum in the pre-operative period, increased significantly in the post-operative period, and, most importantly, higher serum cyclohexanone concentrations were independently associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 12 months.28

In our cohort of pediatric ECMO patients, cyclohexanone was only detected in a minority of patients. However, its metabolites were present in all plasma samples assayed, and higher concentrations on ECMO day 1 were independently associated with unfavorable survival and neurofunctional outcomes at hospital discharge. There are several potential explanations for this finding, the first being that of direct cyclohexanone toxicity. While our parent study focused on neurologic complications and outcomes of children on ECMO support, we did not specifically assess for direct cyclohexanone neurotoxicity during the study period as this was not a pre-planned analysis. We also collected no data related to non-neurotoxic effects of cyclohexanone, such as cardiovascular dysfunction or edema,12,13,24 which could have contributed to worse clinical outcomes.

Another potential explanation is that pediatric ECMO patients receive intensive care therapies that could potentially expose them to cyclohexanone leaching from medical devices other than the ECMO circuit (e.g., cardiopulmonary bypass circuit, intravenous tubing and stopcocks for medication or blood product administration, etc). The higher cyclohexanone metabolite concentrations found in plasma collected on the first ECMO day from children who ultimately had unfavorable outcomes may therefore be related to higher severity of illness and intensity of critical care before or during the ECMO course. More severely ill children may have required multiple intravenous medication infusions, fluids, and parenteral nutrition pre-ECMO or shortly after ECMO cannulation. Moreover, these children may have had more severe multiple organ dysfunction, with inability to excrete cyclohexanone due to kidney injury.14,21,26,27

Since there is no known pathophysiologic mechanism between cyclohexanone exposure and acute neurologic injury as pre-defined in our study (i.e., ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, or asphyxial injury by neuroimaging), we could not readily explain the seemingly protective effect observed between higher cyclohexanone metabolite concentrations and abnormal neuroimaging. We explored this in multivariate analyses, with cyclohexanone metabolites and abnormal neuroimaging as independent variables, and both were significant independent risk factors for unfavorable outcome at hospital discharge. The relationship between cyclohexanone metabolites and abnormal neuroimaging in this population requires further study. It is possible that the observed protective effect was a data artifact related to the smaller sample size of 80 participants.

Lastly, the 3 subjects enrolled prior to the end of January 2011 were supported with circuits including silicone oxygenators that are no longer in use. Roller pumps used in infants <10 kg enrolled in this study are also used less in the contemporary era, with just over half (51%) of all neonates and children being supported with centrifugal pumps as reported in the most recent pediatric ELSO registry international report.2 Various materials are known to have different qualities (e.g., spallation performance differs between Tygon, silicone and LVA tubing)29,30 and modern integrated pump-oxygenators may also have an impact on cyclohexanone exposure during contemporary ECMO. Further investigation to determine whether ECMO patients show evidence of cyclohexanone exposure with modern circuitry, pumps and oxygenators is therefore warranted.

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. As this is a secondary analysis, we had not prospectively sampled intravenous fluids or ECMO circuit contents; however in prior studies of neonates, presence of 1,2- and 1,4-cyclohexanediol was directly linked to cyclohexanone presence in intravenous fluid administration sets.21 Cyclohexanone’s toxicity extends to multiple organ systems as noted in the Discussion, but our study focused on ECMO-related neurologic complications and outcomes. We therefore did not collect data that could have been used to investigate other potential cyclohexanone toxicities. Similarly, details on liver and kidney dysfunction including utilization of renal replacement therapy that could have helped elucidate cyclohexanone toxicodynamics and toxicokinetics were not collected as part of the primary study. It is possible that the higher levels of cyclohexanediol observed were due to worse renal function and a compromised ability to excrete this exogenous chemical. Also, the study design did not allow for evaluation of type and amount of intravenous fluids administered before or during the ECMO course, nor for evaluation of cumulative exposure during the hospital and ECMO course. Lastly, we did not have samples to compare and contrast cyclohexanone metabolite levels in appropriate controls (e.g., pediatric intensive care unit or pediatric cardiac intensive care patients, dialysis), or over time as circuitry technology has evolved. These results provide estimated average levels for this particular population at two sites which used ECMO circuitry that was typical for this time period (2010–2015). Even though this cohort represents a relatively large sample of a unique population receiving a rare and intensive intervention, we hope these findings can inform an investigation of these relationships in larger cohorts and potentially serve as a benchmark for concentrations of cyclohexanone and its metabolites. Potential solutions to minimizing cyclohexanone exposure could include disposing of the initial clear prime and repriming (flushing) circuits, reconfiguring circuits to reduce the number of solvent-based PVC to polystyrene bonding joints (especially important for circuits used in neonates and children) as well as changing manufacturing processes to replace cyclohexanone with safer alternatives.

CONCLUSIONS

Cyclohexanone metabolites were consistently present in the plasma of critically ill children supported on ECMO at two centers that used ECMO circuits from different manufacturers during the study period. Higher plasma concentrations of cyclohexanone metabolites during the first day of ECMO support were independently associated with in-hospital mortality or survival with unfavorable neurofunctional outcomes. More research is needed to identify sources of cyclohexanone exposure and to describe its toxicity profile, toxicodynamics and toxicokinetics in the critically ill child. Potential changes in manufacturing processes or mitigation of toxic effects of cyclohexanone in the critically ill child are also areas of future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients described herein and the medical staff who made their complex care possible.

Funding: Support for this work included funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23NS076674 and R01NS106292 (MMB).

REFERENCES

- 1.Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ELSO registry international summary. https://www.elso.org/Registry/Statistics/InternationalSummary.aspx. Updated 2020. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 2.Barbaro RP, Paden ML, Guner YS, et al. Pediatric extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J. 2017;63(4):456–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle K, Felling R, Yiu A, et al. Neurologic outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation - a systematic review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madderom MJ, Toussaint L, van der Cammen-van Zijp MH, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia with(out) ECMO: Impaired development at 8 years. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98(4):316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madderom MJ, Schiller RM, Gischler SJ, et al. Growing up after critical illness: Verbal, visual-spatial, and working memory problems in neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survivors. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakat S, O’Callaghan M, Smith L, et al. The 1-year follow-up clinic for neonates and children after respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: A 10-year single institution experience. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(11):1047–1054. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001304 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danielson JW. Capillary gas chromatographic determination of cyclohexanone and 2-ethyl-1-hexanol leached from solution administration sets. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1991;74(3):476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falk O, Jacobsson S. Determination of cyclohexanone in aqueous solutions stored in PVC bags by isotope dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1989;7(10):1217–1220. doi: 0731-7085(89)80058-5 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Story DA, Leeder J, Cullis P, Bellomo R. Biologically active contaminants of intravenous saline in PVC packaging: Australasian, european, and north american samples. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005;33(1):78–81. doi: 2004208 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulsaker GA, Korsnes RM. Determination of cyclohexanone in intravenous solutions stored in PVC bags by gas chromatography. Analyst. 1977;102(1220):882–883. doi: 10.1039/an9770200882 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalfi F, Dine T, Luyckx M, et al. Determination of cyclohexamone after derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine in intravenous solutions stored in PVC bags by high performance liquid chromatography. Biomed Chromatogr. 1998;12(2):69–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0801(199803/04)12:23.0.CO;2-0 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta PK, Lawrence WH, Turner JE, Autian J. Toxicological aspects of cyclohexanone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1979;49(3):525–533. doi: 0041-008X(79)90454-X [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koeferl MT, Miller TR, Fisher JD, Martis L, Garvin PJ, Dorner JL. Influence of concentration and rate of intravenous administration on the toxicity of cyclohexanone in beagle dogs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1981;59(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(81)90192-7 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martis L, Tolhurst T, Koeferl MT, Miller TR, Darby TD. Disposition kinetics of cyclohexanone in beagle dogs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1980;55(3):545–553. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(80)90056-3 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Cyclohexanone. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0163.html. Updated 2019. Accessed June 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Superfund Health Risk Technical Support Center, National Center for Environmnetal Assessment, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Provisional peer-reviewed toxicity values for cyclohexanone (CASRN 108–94-1). https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/pprtv/documents/Cyclohexanone.pdf. Updated 2010. Accessed October 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bembea MM, Felling RJ, Caprarola SD, et al. Neurologic outcomes in a two-center cohort of neonatal and pediatric patients supported on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2020;66(1):79–88. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000933 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 1992;121(1):68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiser DH, Long N, Roberson PK, Hefley G, Zolten K, Brodie-Fowler M. Relationship of pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scores at pediatric intensive care unit discharge with outcome measures collected at hospital discharge and 1- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2616–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colareta Ugarte U, Prazad P, Puppala BL, et al. Emission of volatile organic compounds from medical equipment inside neonatal incubators. J Perinatol. 2014;34(8):624–628. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.65 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills GA, Walker V. Urinary excretion of cyclohexanediol, a metabolite of the solvent cyclohexanone, by infants in a special care unit. Clin Chem. 1990;36(6):870–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snell RP. Gas chromatographic determination of cyclohexanone leached from hemodialysis tubing. J AOAC Int. 1993;76(5):1127–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiedmer C, Buettner A. Quantification of organic solvents in aquatic toys and swimming learning devices and evaluation of their influence on the smell properties of the corresponding products. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018;410(10):2585–2595. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-0929-6 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson-Torgerson CS, Champion HC, Santhanam L, Harris ZL, Shoukas AA. Cyclohexanone contamination from extracorporeal circuits impairs cardiovascular function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(6):1926. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00184.2009 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Permanent Senate Commission for the Investigation of Health Hazards of Chemical Compounds in the Work Area. List of MAK and BAT values 2017 (maximum concentrations and biological tolerance values at the workplace). Weinheim, Germany: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2017:248. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mráz J, Gálová E, Nohová H, Vitková D. 1,2- and 1,4-cyclohexanediol: Major urinary metabolites and biomarkers of exposure to cyclohexane, cyclohexanone, and cyclohexanol in humans. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1998;71(8):560–565. doi: 10.1007/s004200050324 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong CN, Sia GL, Chia SE, Phoon WH, Tan KT. Determination of cyclohexanol in urine and its use in environmental monitoring of cyclohexanone exposure. J Anal Toxicol. 1991;15(1):13–16. doi: 10.1093/jat/15.1.13 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everett AD, Buckley JP, Ellis G, et al. Association of neurodevelopmental outcomes with environmental exposure to cyclohexanone during neonatal congenital cardiac operations: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204070. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4070 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peek GJ, Thompson A, Killer HM, Firmin RK. Spallation performance of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation tubing. Perfusion. 2000;15(5):457–466. doi: 10.1177/026765910001500509 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ippoliti F, Piscioneri F, Sartini P, et al. Comparative spallation performance of silicone versus tygon extracorporeal circulation tubing. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;29(5):685–692. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivz170 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.