Abstract

Aim

This study aims to assess the risks and peri-operative morbidity associated with a single-stage sequential bilateral hip arthroplasty (SBHA) when performed in patients with arthritis secondary to inflammatory arthropathy.

Methods

Data of patients who underwent SBHA between 2012 and 2018 for inflammatory arthritis were extracted from a database, for peri-operative complications and functional improvement. SBHA for other causes was excluded.

Results

Data of 84 consecutive patients with a mean age of 34.5 years were analyzed. The mean follow-up was 2.4 years. 66% had ankylosing spondylitis, while 14% had rheumatoid arthritis. 50% of the patients had bilateral fusion of the hips, and 34% had flexion deformity > 30°.

None of the patients had peri-operative cardiac or pulmonary complications. 2.4% had per-operative hypotension (MAP < 50 mmHg) and 1.2% had desaturation (SpO2 < 90%). The mean drop in hematocrit was 9.3%. While 31% did not require blood transfusion, 35% required more than 1 unit of blood. Patients with pre-operative PCV of > 36% had a significantly lower risk of being transfused > 1 unit of blood (p = 0.02). ICU admission was 6%—mostly for post-operative monitoring. While one patient had a local hematoma that needed a wash-out, there were no infections, dislocations, or mortality in these patients. The modified Harris hip score improved from a mean of 26.5–85. The mean hip flexion improved post-operatively from 32° to 92°.

Conclusions

SBHA for inflammatory arthritis can be performed with minimum complications in a multidisciplinary setting. Pre-operatively, PCV of > 36 is advised to reduce transfusion rates.

Keywords: Stiff hip, Bilateral hip arthroplasty, Ankylosing spondylitis, Inflammatory arthritis, Morbidity

Introduction

Inflammatory arthritis is often polyarticular, and can lead to significant functional disability. If the arthropathy is diagnosed and treated early, the need for surgical intervention is limited. Due to the lack of knowledge and understanding of the disease, several patients seek treatment late and present with significant bilateral hip arthritis requiring surgical management.

Though there have been contradictory reports regarding the safety profile of bilateral sequential arthroplasty, significant potential advantages including single anesthesia, reduced hospital stay, lower overall costs and a single rehabilitation phase have been clearly established [1–5]. However, other studies have shown an increased risk of complications associated with bilateral sequential total joint arthroplasty—the commonly cited complications include increased blood transfusion requirement, higher risk of pulmonary embolism, cardiac and other systemic complications [6, 7]. In patients with inflammatory arthritis, there is an additional risk posed by the medications used to treat the disease—with an increased risk of infection and peri-operative bleeding [8]. In addition, the hips are often fused or significantly deformed, and the bones significantly osteoporotic. In such conditions, critics state the risks would be too high. Due to this discrepancy in reported safety, many surgeons prefer to err on the side of caution and offer a staged approach in inflammatory arthritis.

For the past couple of decades, we have been performing bilateral sequential hip replacement for patients with hips affected with inflammatory arthritis—including the ones with fused hips and with flexion deformities at the same sitting. All patients are discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting, with input from the rheumatologist, anesthetist, orthopedist, and the rehabilitation department. The purpose of this study was to audit the morbidity and peri-operative complications associated with single-stage bilateral sequential hip arthroplasty in these complex hips, in the setting of a multidisciplinary team approach.

Methods

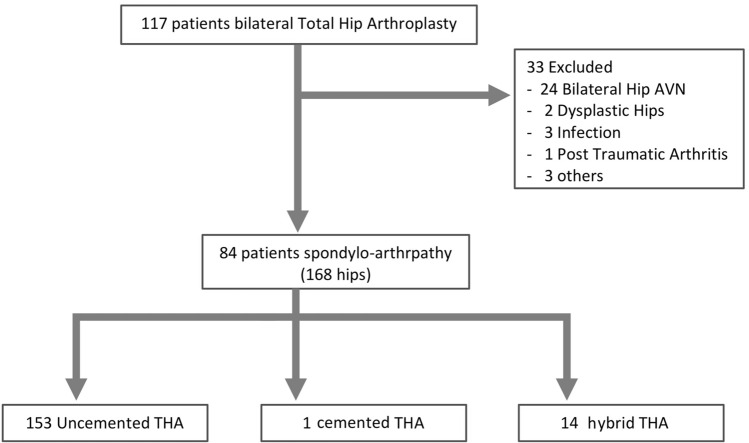

This is a descriptive study of 84 consecutive patients who underwent bilateral sequential total hip arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis at a tertiary care center in South India between the years 2012 and 2018. Patients who had sequential arthroplasty for arthritis secondary to other pathologies like infection, dysplasia or avascular necrosis due to other causes were excluded from the study, as were patients who had a staged procedure under two different anesthesias. All data were entered into a data base, with parameters including peri-operative local and systemic complications, transfusion rates, functional and clinical improvement. All patients were reviewed daily for the first 12–14 days, and follow-up data were collected at 6 months and every alternate year thereafter. As shown in the strobe flowchart (Fig. 1), data for 84 consecutive patients (168 hips) were extracted to analyze the immediate and late morbidity rates. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for the retrospective study.

Fig. 1.

STROBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) pathway

Based on the pre-operative assessment and ASA grading, the anesthetist decided on the type of anesthesia—spinal–epidural or general anesthesia. Spinal–epidural was the first choice of anesthesia; but when the posterior ligaments in the spine precluded it, general anesthesia was given. Fibre-optic intubation was performed when indicated.

Intra-operative complications such as hypotension (mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 50 mmHg for more than 5 min) [9], desaturation (SpO2 < 90%) and arrhythmias were noted [9]. Local complications including hematoma, wound break-down, infections, peri-prosthetic fractures and dislocations were documented. In the peri-operative period, complications such as deep vein thrombosis, and systemic complications such as pulmonary embolism, myocardial ischemia, cerebrovascular injury, urinary retention, pneumonia, paralytic ileus and electrolytic imbalance were noted. The other parameters assessed included peri-operative blood loss, rate of ICU admission, blood transfusion rates, readmission and mortality rates. Patients received blood transfusion post-operatively, only if the packed cell volume (PCV) was < 22%, or < 24% and symptomatic. Per-operative transfusion was at the discretion of the anesthetist, based on per-operative blood loss and the clinical status.

All patients had the surgery in the lateral position through the modified Hardinge anterolateral approach [10], as was the standard practice for all bilateral hip arthroplasty at the institution. Where the femoral head could not be dislocated, osteotomy of the neck was performed in situ. Where the joint was fused, acetabular reaming was done over the femoral head, to the size determined by pre-operative templating. Limb length correction was assessed with pre-operative templating [11], and was corrected per-operatively using the pin-caliper device used for measuring femoral offset and leg length (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN) [12]. This device relies on repeated measurements of the distance between fixed points on the ilium and the femur, with an iliac pin inserted just above the acetabular roof, and another pin against the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter with the hip in the maximum extension possible (before dislocation). After reduction of the trial implants, with the limb in the same position as the pre-dislocated position, changes in leg length and offset were assessed and corrected [12]. No X-rays were used per-operatively.

After skin closure was completed for the first hip, the patient was turned to the opposite side and the second side was operated on. Surgery time was logged as the time between skin incision for the first side, to skin closure of the second side; and included the time taken to reposition the patient for the second hip. Three doses of tranaxemic acid at three hourly intervals were used for all patients, starting 15 min before skin incision for the first hip, at 10–15 mg/kg [13]. Pericapsular injection of a cocktail of analgesic drugs was used for post-operative pain control [14]. All the patients had surgical drains, which were retained post-operatively for duration of 24 h. Patients received 2 days of IV antibiotics and were ambulated from the second post-operative day. Anticoagulation was given as per the institutional policy—with Enoxaparin for 10 days, followed by Tab. Aspirin for 4 weeks. Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatoid Drugs were managed by the rheumatologist, as per the guidelines provided by the American College of Rhuematology [15]. No prophylaxis for heterotrophic ossification (HO) was used..

All patients were reviewed daily for the first 12–14 days and then followed up at 6 months, and thereafter at every alternate year by the Rheumatologist, Orthopaedist and the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation department. The functional assessment was done using the modified Harris Hip Scores [16], and the improvement in the range of movement and residual deformity was assessed at each follow-up visit to the outpatient clinic..

Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of the patients who underwent a bilateral sequential total hip arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis were described using relative frequencies for categorical variables and means or medians with measures of spread (SD or IQR) for continuous variables. Chi-square test was used to compare the complication rate with categorical variables. Logistic regression was used for the outcome of complication with confounding variables. Unadjusted odds ratios were reported with 95% Confidence interval. A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the statistical package STATA IC, version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

117 patients underwent sequential bilateral total hip arthroplasty during the period of September 2012–July 2018 at our center. Of these, 84 patients (168 joints) had arthritis secondary to inflammatory arthropathy. The median follow-up period was 2.4 years (IQR 2.2–6.1 years).

The mean age of the patients was 34.5 years (range 16–76). All but one patient were less than 70 years of age. The median pre-operative P.C.V was 34.8 (IQR 28–48). The type of inflammatory arthritis and the associated comorbidities are shown in Table 1. The type of anesthesia used and ASA risk assessment are also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Number of patients (hips) | 84 patients (168 hips) |

| Male: female | 69: 25 |

| Mean age (range) | 34.5 years (16–76) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 55 (66%) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | 12 (14%) |

| Psoriatic arthropathy | 5 (6%) |

| Juvenile inflammatory arthritis | 3 (4%) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (2.5%) |

| Other undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis | 7 (8%) |

| Other comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 3 (4%) |

| Hypertension | 12(15%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2 (2.5%) |

| Asthma | 2 (2.5%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (2.5%) |

| BMI > 35 | 0 |

| No other comorbidity | 67 (80%) |

| Type of anesthesia | |

| GA | 72 (86%) |

| Spinal/epidural | 12 (14%) |

| ASA grading | |

| ASA 1 | 13 (16%) |

| ASA 2 | 65 (77%) |

| ASA 3 | 6 (7%) |

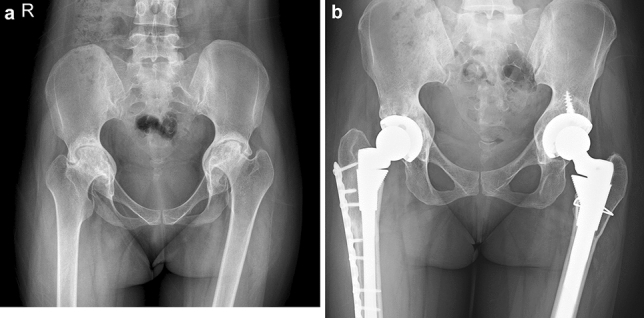

42 (50%) of the patients studied had bilateral fused hips (Fig. 2). Eleven (13%) patients had a fused hip on one side, while the other hip had limited flexion (range 20°–70°) that was painful. The remaining 31 (37%) patients had some pre-operative movement in both hips (range 20°–80° of flexion), but as both hips were painful and caused significant functional disability, bilateral hip replacement was performed. 29 (34%) patients had a fixed flexion deformity of > 30°, of which 15 (51%) had a flexion deformity of > 50°. The mean range of pre-operative hip flexion was 32°, while post-operative hip flexion was 92° (range 45–110).

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative AP view (a) and Post-operative AP view (b) radiographs of a patient with bilateral ankylosis of the hips, who underwent an uncemented bilateral total hip replacement

At the time of surgery, 16 hips (9%) required bone grafting for the protrusio acetabulum (Fig. 3), and 4 (2.5%) hips required femoral shortening osteotomy for reduction, as there was significant pre-operative shortening of the limb. The latter 4 hips were in patients with end stage rheumatoid arthritis.

Fig. 3.

Pre-operative AP view (a) and 2-year post-operative AP view (b) radiographs of a patient with Rheumatoid arthritis, who required femoral shortening osteotomy and bone grafting for protrusio

153 hips underwent uncemented hip replacements, while 14 were hybrid, and 1 had cemented hip replacements. The 4 hips that required femoral shortening had a SROM femoral stems (DePuy Orthopedics Inc., Warsaw, IN).

There were 12 (14.3%) patients with associated flexion deformities of the knees—bilateral in 7 and unilateral in 5 patients. The mean flexion deformity in these 12 patients was 21.57°. None of them required surgery, as the knee deformities were corrected with physiotherapy/casting to less than 10° peri-operatively.

The overall incidence of intra-operative complication was 3.5%—in all patients with fused hips. Two (2.4%) patients had hypotension (MAP < 50 mmHg for > 5 min) during surgery, while one patient had a desaturation of SpO2 < 90% during the surgery. None of the patients had peri-operative cardiac arrhythmia.

The mean drop in hematocrit following surgery was 9.3%. The median pre-operative P.C.V was 34.8% (IQR 28–48), while the post-operative PCV was 26.5% (IQR 24.4–29.8). A third of the patients (26/84) did not require any blood during the peri-operative period. 30 (35%) patients required more than one unit of blood and 7 (8%) patients required more than 2 units of blood transfused peri-operatively. 18 of the 53 patients (34%) who had ankylosed hips, required more than 1 unit of blood, whereas 12 of 31 patients who did not have fused hips (39%), required more than a unit of blood. This difference was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.32–2.04, p = 0.66), indicating that in this series, presence of bony fusion did not have a bearing on the transfusion rates (Table 2). The presence of a flexion deformity too did not affect the transfusion rates—with 10 of 29 patients with flexion deformity > 30° requiring more than 1 unit of blood, as compared to 20 of 55 patients without flexion deformities (95% CI 0.35–2.3, p = 0.86). The starting PCV was an important factor that affected the transfusion rates. The odds of having more than a unit of blood was 3.28 times higher in those with a starting PCV of < 36% (95% CI 1.2–8.9, p = 0.02) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for risk of transfusion of more than one unit of blood

| Variables | > 1 unit (n = 30) | ≤ 1 unit (n = 54) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankylosed hips (yes) | 18 (60.0%) | 35 (64.8%) | 0.81 (0.3–2.0) | 0.81 (0.3–2.2); p = 0.66 |

| Flexion deformity (≥ 30°) | 10 (33.3%) | 19 (35.2%) | 0.92 (0.4–2.4) | 1.07 (0.4–3.1); p = 0.86 |

| Starting PCV (≤ 36) | 23 (76.7%) | 27 (50.0%) | 3.28* (1.2–8.9) | 3.29 (1.2–8.9); p = 0.02 |

The median duration of surgery was 186 min (IQR 160–202 min). This included the time taken to reposition the patient between the two sides, and draping of the second hip. Patients with a flexion deformity of > 30° had a mean duration of surgery of 200 min, while those with a flexion deformity > 50° took a mean of 192 min. Patients who had central bone grafting for protrusio took an average of 200 min, while those who had femoral shortening required 225 min.

One patient had a local hematoma post-operatively in one hip which required a wash-out. None of the patients had dislocations, wound break-down, deep vein thrombosis, or infections. Five femurs required prophylactic wiring of the calcar as there were minor calcar cracks intra-operatively. There were no major peri-prosthetic fractures. Two of the hips had Bookers grade 2 heterotrophic ossification post-operatively at follow-up. There was no cup loosening or migration at follow-up.

There were no systemic complications such as peri-operative pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, urinary retention, paralytic ileus or cerebrovascular events.

The overall incidence of HDU admission in the study was 6%. Two patients were admitted for monitoring as the duration of surgery was prolonged; one patient was admitted for delay in extubation following surgery and another patient was admitted for monitoring of abnormal metabolic parameters following surgery. None required post-operative ventilation.

At each review, a Modified Harris Hip Score was used to assess the functional outcomes in the patients, both pre-operatively and post-operatively [16]. The mean pre-operative Modified Hip Score was 26.5 (range 4–66) and the post-operative hip score was 85 (range 71–92). During this limited follow-up, none of the patients had radiological loosening or required revision.

Discussion

There is a large volume of literature that supports the fact that single-stage bilateral hip arthroplasty is a safe procedure, when performed on select patients [1–5]. It was found that individuals younger than 75 years of age, without risk factors such as cardiovascular disease or respiratory compromise and with low comorbidities (ASA 1 and 2) have a lower risk of complications when undergoing a single-stage procedure [1–5]. There is, however, little information on the safety and outcomes of bilateral sequential hip replacements in patients who have been diagnosed with inflammatory arthritis.

Though the patients in our study were mostly young patients, with a mean age of 34 years, most had complex pathologies in the hips. 66% of the patients had fused hips, and 35% had a fixed flexion deformity of > 30°. This represents a group of patients who are at an increased risk of peri-operative complications. Additionally, the medications used for treatment of the inflammatory arthritis lend themselves to an increased risk of infection and bleeding. It was, therefore, necessary to audit the safety of bilateral sequential hip surgery in this scenario.

Li et al. and Bhan et al., used a dual approach to address the fused hips in ankylosing spondylitis—with the anterior approach to osteotomize the neck, and the posterior approach to ream and implant the cup [17, 18]. We found the anterolateral approach to the hip to be simpler, as it was possible to osteotomize and implant the cup through the same approach. For surgeons trained only in the posterior approach, the dual approach may be more appropriate, as the hips are often fused in a flexed, abducted and externally rotated position, and therefore difficult to osteotomize from the posterior. Unlike Bhanet al who reported a 4% dislocation rate with the dual approach, none of our patients had dislocations using the modified anterolateral approach [17].

Patients with fused hips often have limited spino-pelvic movement, and as this has a bearing on the anteversion of the cup, there is a higher risk for dislocation [19, 20]. There is an additional risk posed by the difficulty in positioning the patient in the lateral position (Fig. 4). Some surgeons advocate the use of dual mobility to reduce the incidence of dislocation [21]. However, this study suggests that this is not required in arthroplasty for hips fused secondary to inflammatory arthritis. It is probably more important to get the cup and stem positioned appropriately, keeping in mind the altered spino-pelvic rotations.

Fig. 4.

Positioning of a patient with bony anklylosis and flexion deformity of the hips for surgery

Blood loss was a significant morbidity in this study, with 35% requiring more than one unit of blood. However, about a third of the patients undergoing bilateral hip replacement did not require any blood transfusion. In this series, neither the presence of flexion deformities or bony ankylosis had a bearing on transfusion rates, indicating that in a multidisciplinary setting, surgery is relatively safe. The risk of requiring more than one unit of blood peri-operatively was 3.3 times higher if the pre-operative PCV was less than 36%. These transfusion rates are similar to other series of bilateral hip arthroplasty, that include patients with other pathologies as well [6, 7]. The incidence of per-operative complications like hypotension and desaturation was low in this study population. Additionally, there were no post-operative cardio-pulmonary complications that are commonly associated with such bilateral arthroplasty surgeries.

Through the retrospective analysis, we have demonstrated that with meticulous pre-operative preparation, the intra-operative and post-operative complications can be significantly reduced to that seen in unilateral hips [4, 5]. Blood loss, as is to be expected, is however more than that seen in unilateral hip arthroplasty—but not more than that seen in patients who have had bilateral hip arthroplasty for other pathologies [2, 3, 6, 7]. Medications were reviewed and the patients were optimized for surgery with the help of the rheumatologists. All patients were reviewed by senior anesthetists pre-operatively, and fibreoptic assisted intubation was performed where necessary. In most cases, two senior surgeons operated together, along with an experienced team, to reduce the morbidity. Intravenous Tranaxemic acid to reduce blood loss and pericapsular injections for pain control were used peri-operatively. We believe that all these steps were critical in keeping the peri-operative complications low—the most crucial being the interdisciplinary team approach. Only 6% of our patients required an ICU admission for a day—mostly for blood loss and monitoring.

The choice between sequential and staged bilateral hip arthroplasty remains controversial—especially as the blood loss and time under a single anesthesia is more in bilateral hip arthroplasty. However, Parvizi et al. demonstrated that there is no difference in systemic complications between unilateral hip arthroplasty and sequential bilateral hip arthroplasty [22]. Aghayev et al. in a study with 1819 patients demonstrated that patients who underwent sequential bilateral hip arthroplasty have a lower rate of major systemic complications when compared with two-staged bilateral hip arthroplasty [2]. As Rasouli et al., pointed out, patients with two-staged bilateral hip arthroplasty theoretically experience twice the risk of a single surgery [4].

On the functional front, there was a significant improvement following a bilateral sequential total hip arthroplasty, with a mean post-operative Modified Harris Hip Score of 85. The rapid recovery and post-operative physiotherapy were made possible with minimal risks and complications because of the single-stage bilateral total hip replacement offered to the patients, like in other studies (Table 3). Wykman et al. found that in patients with bilateral hip disease, optimal function is not achieved until both hips have been replaced [27]. Bangjian et al., in their series of 12 patients with bilateral ankylosed hips showed high patient satisfaction and function following synchronous bilateral hip arthroplasty [23]. Lin et al., in a recent review of literature observed that the improvement in the function and mobility was more marked in the series with bilateral THA as compared to those in the staged THA groups [28]. This is probably because of the fact that the patient had limited mobility during the intervening period of the staged THA.

Table 3.

Outcome of bilateral simultaneous hip arthroplasty for stiff hips

| References | Number of patients/hips | Mean follow-up (in months) | Complications | Critical per-operative anesthetic events | Blood loss | Mean HHS at follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangjian et al. [23] | 12/24 | 50.4 |

2 Femoral fractures 1 Femoral Nerve Neuropraxia 3 Heterotrophic ossification No dislocations |

NA | NA | 86.3 |

| Wang et al. [24] | 13/26 | 128 |

2 calcar fractures 1 Femur fracture 5 Heterotrophic ossification 1 Peroneal nerve Neuropraxia 3 osteolysis No dislocations |

NA | NA | 91.7 |

| Ye et al. [25] | 15/30 | 29.3 |

1 Femoral nerve Neuropraxia 1 Wound infection 1 Dislocation |

NA | NA | 83.8 |

| Feng et al. [26] | 17/34 | 30 |

1 Acetabular over reaming 2 Femoral fractures 3 Acetabular osteolysis 2 Wound infections 1 Sciatic nerve palsy 4 Heterotrophic ossifications 1 Anterior dislocation |

NA | 580 ml (450–1000 ml) | 65.8 |

| Current study | 84/168 | 28.8 |

5 Calcar fractures 1 Wound hematoma 2 Heterotrophic ossifications No Dislocations |

Per-op Hypotension-2 Per-op Desaturation-1 |

Mean drop in Hb—3.1 gm/dl | 82.6 |

NA not available, HHS Harris hip score

Though all peri-operative details were well documented in the data base, it must be acknowledged that this study is a retrospective extraction of outcomes. Further, one cannot compare these results to that of staged arthroplasty, as a comparative cohort was not studied. We also acknowledge that most of our patients were young, with few associated comorbidities. Though all patients had hips damaged secondary to inflammatory arthritis, there is heterogenicity in the group of patients studied. As the period of follow-up is limited, one cannot comment on the long-term outcome of these patients.

In conclusion, the study indicates that despite the risks associated with inflammatory arthritis, bilateral sequential hip arthroplasty in these patients can be safe, when done in a multidisciplinary setting. The risk of transfusion is found to be significantly higher in patients with a pre-operative PCVof less than 36%. Additionally, the risk of dislocations, infection and other peri-operative complications are low, when done in an appropriate setting.

Author contributions

Concepts: AIC, PMP. Design: RG, VJC, AIC, PMP. Definition of intellectual content: RG, VJC, AIC, ATO, PMP. Literature search: RG, VJC, AIC, AAS, PMP. Data collection: RG, VJC, AIC, TDH, AAS. Data analysis: RG, VJC, AIC, AAS, BA, PMP. Manuscript preparation: RG, VJC, AIC, TDH, BA, ATO, PMP, Manuscript editing: RG, VJC, AIC, TDH, AAS, BA, ATO, PMP. Manuscript review: RG, VJC, AIC, TDH, AAS, BA, ATO, PMP. Guarantor: RG, VJC, AIC, PMP.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rahul George, Email: rahulgt@gmail.com.

V. J. Chandy, Email: vjchandy@gmail.com

A. I. Christudoss, Email: andy.isaac90@gmail.com

T. D. Hariharan, Email: drhariharantd@gmail.com

A. ArunShankar, Email: drarunshankar11@gmail.com

B. Antonisamy, Email: b.antonisamy@gmail.com

A. T. Oommen, Email: lillyanil@cmcvellore.ac.in

Pradeep Mathew Poonnoose, Email: pradeep.cmc@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Calabro L, Yong M, Whitehouse SL, Hatton A, de Steiger R, Crawford RW. Mortality and implant survival with simultaneous and staged bilateral total hip replacement: Experience from the Australian Orthopedic Association national joint replacement registry. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2020;35(9):2518–2524. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aghayev E, Beck A, Staub LP, et al. Simultaneous bilateral hip replacement reveals superior outcome and fewer complications than two-stage procedures: A prospective study including 1819 patients and 5801 follow-ups from a total joint replacement registry. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2010;11:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romagnoli S, Zacchetti S, Perazzo P, Verde F, Banfi G, Viganò M. Simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasties do not lead to higher complication or allogeneic transfusion rates compared to unilateral procedures. International Orthopaedics. 2013;37(11):2125–2130. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houdek MT, Wyles CC, Watts CD, et al. Single-anestheticversus staged bilateral total hip arthroplasty: A matched cohort study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2017;99(1):48–54. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glait SA, Khatib ON, Bansal A, et al. Comparing the incidence and clinical data for simultaneous bilateral versus unilateral total hip arthroplasty in New York State between 1990 and 2010. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2015;30(11):1887–1891. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berend ME, Ritter MA, Harty LD, et al. Simultaneous bilateral versus unilateral total hip arthroplasty an outcomes analysis. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2005;20(4):421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blizzard DJ, Penrose CT, Sheets CZ, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis increases perioperative and postoperative complications after total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017;32(8):2474–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monk TG, Bronsert MR, Henderson WG, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and hypertension and 30-day postoperative mortality in noncardiacsurgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(2):307–319. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frndak PA, Mallory TH, Lombardi AV. Translateral surgical approach to the hip. The abductor muscle ‘split’. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1993;295:135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perumal R, Krishnamoorthy VP, Poonnoose PM. Templating digital radiographs using acetate templates in total hip arthroplasty. JAJS. 2017;4:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolhain P, Tsigaras H, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Mac Donald S, McCalden R. The effectiveness of dual offset stems in restoring offset during total hip replacement. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2002;68(5):490–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, et al. Tranexamic acid in total joint arthroplasty: The endorsed clinical practice guides of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Hip Society, and Knee Society. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 2019;44:7–11. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2018-000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srampickal GM, Jacob KM, Kandoth JJ, et al. How effective is periarticular drug infiltration in providing pain relief and early functional outcome following total hip arthroplasty? Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics & Trauma. 2019;10(3):550–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman SM, Springer B, Guyatt G, et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology/American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Guideline for the Perioperative Management of Antirheumatic Medication in Patients With Rheumatic Diseases Undergoing Elective Total Hip or Total Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):2628–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar P, Sen R, Aggarwal S, Agarwal S, Rajnish RK. Reliability of modified harris hip score as a tool for outcome evaluation of total hip replacements in Indian population. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2019;10(1):128–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhan S, Eachempati KK, Malhotra R. Primary cementless total hip arthroplasty for bony ankylosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6):859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Wang Z, Li M, Wu Y, Xu W, Wang Z. Total hip arthroplasty using a combined anterior and posterior approach via a lateral incision in patients with ankylosed hips. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2013;56(5):332–340. doi: 10.1503/cjs.000812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefl M, Lundergan W, Heckmann N, et al. Spinopelvic mobility and acetabular component position for total hip arthroplasty. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2017;99-B:37–45. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0415.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ike H, Dorr LD, Trasolini N, Stefl M, McKnight B, Heckmann N. Spine–pelvis–hip relationship in the functioning of a total hip replacement. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2018;100(18):1606–1615. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel MP. Simplifying the hip–spine relationship for total hip arthroplasty: When do i use dual-mobility and why does it work? Journal of Arthroplasty. 2019;34(7):S74–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parvizi J, Pour AE, Peak EL, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. One-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty compared with unilateral total hip arthroplasty: A prospective study. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2006;21:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangjian H, Peijian T, Ju L. Bilateral synchronous total hip arthroplasty for ankylosed hips. International Orthopaedics. 2012;36(4):697–701. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1313-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, Huang G, Huang T, Wu R. Bilaterally primary cementless total hip arthroplasty in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;11(15):344. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye C, Liu R, Sun C, et al. Cementless bilateral synchronous total hip arthroplasty in ankylosing spondylitis with hip ankylosis. International Orthopaedics. 2014;38(12):2473–2476. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng D-X, Zhang K, Zhang Y-M, et al. Bilaterally primary cementless total hip arthroplasty for severe hip ankylosis with ankylosing spondylitis. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2016;8(3):352–359. doi: 10.1111/os.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wykman A, Olsson E. Walking ability after total hip replacement. A comparison of gait analysis in unilateral and bilateral cases. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1992;74(1):53–56. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin D, Charalambous A, Hanna SA. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty in ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review. EFORT Open Reviews. 2019;4(7):476–481. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]