Abstract

Behavioral skills training (BST) has been demonstrated to be an effective method for training staff to perform skills with high fidelity in a relatively short amount of time. In the current study, three components of direct instruction (DI) were trained using BST. The participants were two classroom instructors with prior experience implementing DI with students with autism. The targets for staff training were accuracy with signal delivery, error correction, and delivery of praise. A multiple-baseline design across skills was used to evaluate the effects of BST for each participant. Generalization probes were conducted with a student with autism during baseline and after mastery with each skill was demonstrated. BST rapidly increased staff performance across skills, with generalization demonstrated during classroom probes. This study extends the use of BST to training staff to implement DI, and the results suggest that BST resulted in improved teacher performance of the targeted skills during generalization probes with students.

Keywords: Behavioral skills training, Direct instruction

Direct instruction (DI) is a method of teaching students that uses specific scripted lessons delivered on a schedule that promotes learning in small increments. DI has been shown to be effective for diverse groups of learners, including students in special education programs (Kubina et al., 2009). In order to effectively deliver a DI lesson as prescribed, instructors must be fluent in several key skills, some of which may not be explicitly scripted, as the instructors’ responses may vary depending on the students’ responses.

The training model recommended by the National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI) consists of 3 to 5 days of preservice training for teachers. The training is similar to behavioral skills training (BST), as it is composed of a program overview and rationale, simulated practice, and feedback from an NIFDI trainer. However, residential treatment programs may not have the resources to provide this level of training to all of their staff. Common training procedures in residential treatment programs involve staff members participating in classroom lectures that may not include demonstrating competency with the target skills. However, research on staff training indicates that lectures alone may not improve job performance (Parsons et al., 2012).

BST is an instructional model that is effective for training staff a variety of skills, including implementing language assessments (Barnes et al., 2014), preference assessments (Weldy et al., 2014), and communication systems (Homlitas et al., 2014). BST involves the trainer (a) providing instructions of the target skill, (b) modeling or demonstrating the target skill, (c) rehearsing or providing opportunities to practice the skill, (d) and providing feedback about the performance. Training continues until the trainee meets a specified level of mastery (Loughrey et al., 2014).

To date, researchers have not evaluated BST used to train staff to implement DI lessons. The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effects of BST used to train staff on three skills used during DI lessons. BST was selected as the participants received regular feedback on their implementation of DI lessons yet failed to demonstrate proficiency with the identified skills. Student (i.e., confederate) responses were scripted during role-plays conducted in baseline, BST sessions, and posttraining sessions. Generalization probes were conducted with students during baseline and following mastery of a skill during simulated practice.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were two adult instructors who taught at a private residential school for children with developmental disabilities. Participant 1 was a White male in his late 20s. Participant 2 was a Latina female in her mid-20s. Prior to participation in the study, both participants received training in DI consisting of 4 hr of lecture-based instruction that culminated in a written exam used to assess competence with DI procedures and philosophy. The initial training for the participants occurred during staff orientation, 16 months and 4 years prior to the study, respectively. The participants implemented group and one-to-one DI lessons with their students at least one time per week and received feedback from supervisors on their performance at least one time per month.

Setting

All training sessions occurred at the school in a conference room with a table and three chairs. The first author provided the BST while the second author other played the role of the student during training, or vice versa. For the first participant, the student probes were conducted in the conference room. Student probes for the second participant occurred in the student’s classroom. The student’s classroom contained five small tables, a teacher’s desk, several bookcases, and a variety of classroom decor. Seven other students and three to four staff were also present in the class. During the probes, the student sat beside the experimenter at a table away from other students working in the environment.

Materials

Lesson 1, Exercises 1–4, from the Language for Learning (Engelmann & Osborn, 2008) presentation book were used as training lessons and student probes for Participant 1. For Participant 2, the same lessons were used for training; however, for student probes conducted in a live classroom setting, the student’s current DI lessons were used. An Apple iPad was used to film all training sessions.

Dependent Variable and Measurement

The dependent variable was the percentage of correct responses in each session. This percentage was calculated by summing the number of occurrences when the participant performed the skill and dividing the sum by the total number of opportunities to perform that skill. For signal delivery, participants used the “hand-drop” procedure or the “point” procedure as prescribed in the lesson plan. A hand-drop response was scored correct if a hand was raised to approximately eye level with the elbow at approximately 90o and then dropped rapidly downward at the time it was prescribed in the script. Approximations (half-raised hands, fingers only) or the use of other signals was scored as incorrect. A point response was scored correct if the index finger of the participant made contact with the corresponding picture in the book, without obscuring the image for the student to see. Including the programmed errors, there were 29 opportunities for signal delivery. For delivery of praise, participants were required to provide verbal praise after each correct response (i.e., “Good job,” “Well done,” “That’s right,” etc.) within 2 s. Failing to deliver praise for correct answers, delivering praise after 2 s for a correct response, delivering praise when it was scripted to be withheld (during error corrections), or making unclear or incomplete praise statements (i.e., “mm-hmm”) was scored as incorrect. Praise after every correct response was used, as most students in this program required a dense schedule of reinforcement. There were 14 opportunities to deliver praise during training. The error correction procedure was scored as a correct response if the participant (a) modeled the correct response, (b) led or stated the question and correct response with the student; (c) repeated the question for the student to respond on his own, and (d) restarted the lesson from the beginning. Each participant was presented with 4 errors to correct per lesson, for a total of 16 per participant.

Experimental Design

A multiple-baseline design across skills was used to evaluate BST for each participant. Generalization probes were conducted with students during baseline after participants met the mastery criteria for each skill.

Procedure

Baseline

Role-plays were conducted with an experimenter playing the role of the student (i.e., confederate). Participants were provided DI manuals and instructed to complete specific lessons (i.e., Lesson 1, Exercises 1–4). During each lesson, the confederate had a predetermined script indicating whether to respond correctly or incorrectly to the participant. No programmed consequences were provided for the participants’ correct or incorrect responses during baseline.

Behavioral Skills Training

Experimenters taught target skills to the participants using a BST model. Training began with a vocal description of the target skill, followed by the trainer modeling the skill. Next, the participants practiced the target skill in role-play situations, using the same lessons as in baseline, and received corrective and positive feedback for their performance. The confederate followed a script that indicated when to respond correctly and when to err. Scripted errors were the same across participants during training. The types of errors committed included incorrect vocal responses (e.g., saying the wrong name of an item) or incorrect motor responses (e.g., waving when told to stand up). During booster sessions, errors were specific to the target behavior. Training continued until the participant met the mastery criteria, which was completing two lessons with at least 90% correct. For each targeted skill, the participant had to meet the mastery criterion and complete a student probe before moving on to the next skill. If a student was not available to participate in a probe session, additional sessions were run prior to the student probe. For Participant 1, the first skill targeted was signaling, followed by error correction and praise delivery. For Participant 2, the first skill targeted was praise delivery, followed by signaling and error correction.

Booster Session

Booster sessions were administered during the praise-delivery phase. For Participant 1, the booster session was implemented even though he met the mastery criterion, with the goal of increasing the accuracy of praise delivery to the levels of the signal and error correction (i.e., 100%). For Participant 2, the booster session was delivered after three sessions when her accuracy improved but she failed to meet the criterion. The booster session specifically targeted withholding praise during parts of the error correction procedure. Specifically, the DI error correction procedure required participants to repeat prior steps of a lesson even if they were previously correct, but to withhold praise for those steps and withhold praise for modeled responses and responses made with the instructor.

Posttraining Session

Posttraining sessions were conducted identically to baseline sessions. The confederate followed a script indicating when to respond correctly or incorrectly. No programmed consequences were provided for correct or incorrect responses during posttraining sessions.

Generalization Probes

Generalization probes with students were conducted during baseline and once a participant met the mastery criterion in simulation. Participant 1 used the same lessons used during training. Participant 2 used the DI lesson on which the students were working and extended across two different students. No programmed consequences were provided for correct or incorrect responses during student probes.

Follow-Up

Lessons were run with a student 4 weeks following the completion of the study. The participants taught the same lessons that were used during training sessions.

Social Validity

The experimenters asked participants to rate their experience with the BST procedures used in the study. A 10-question survey (see Table 1) was administered where participants rated the acceptability of the training and their training preferences using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Both participants anonymously completed social validity questionnaires immediately following the study. The questionnaires were completed on paper, and the researchers were not present at the time.

Table 1.

Social validity data

| Measure | Participant 1 | Participant 2 |

|---|---|---|

| I found this approach to be an acceptable way to learn DI techniques. | 5 | 5 |

| I would be willing for this procedure to be used again to teach me other skills. | 5 | 5 |

| I liked the procedures used in training. | 4 | 5 |

| I believe this training was effective in teaching the techniques to be used in DI. | 5 | 5 |

| I preferred this style of training over other methods. | 4 | 5 |

| I was uncomfortable having observers watch me peform the target skills during my training. | 3 | 2 |

| I believe the training is likely to result in permanent improvement in my ability to implement DI. | 4 | 5 |

| I valued the immediate feedback that was provided after my performances. | 5 | 5 |

| I think other staff would benefit from the training. | 5 | 5 |

| Overall, I had a positive reaction to the training. | 4 | 5 |

Note. 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree. DI = direct instruction; BST = behavioral skills training.

Interobserver Agreement

All sessions were video recorded and scored by two independent observers for 44% and 33% of sessions for Participant 1 and Participant 2, respectively. An agreement was defined as both observers scoring the target response as correct or incorrect. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and converting the result to a percentage. Mean agreement for Participant 1’s responding was 97.98% (signal), 97.9% (praise delivery), and 97.26% (error correction). Mean agreement for Participant 2 was 96.7% (signal), 95.96% (praise delivery), and 93.64% (error correction).

Results

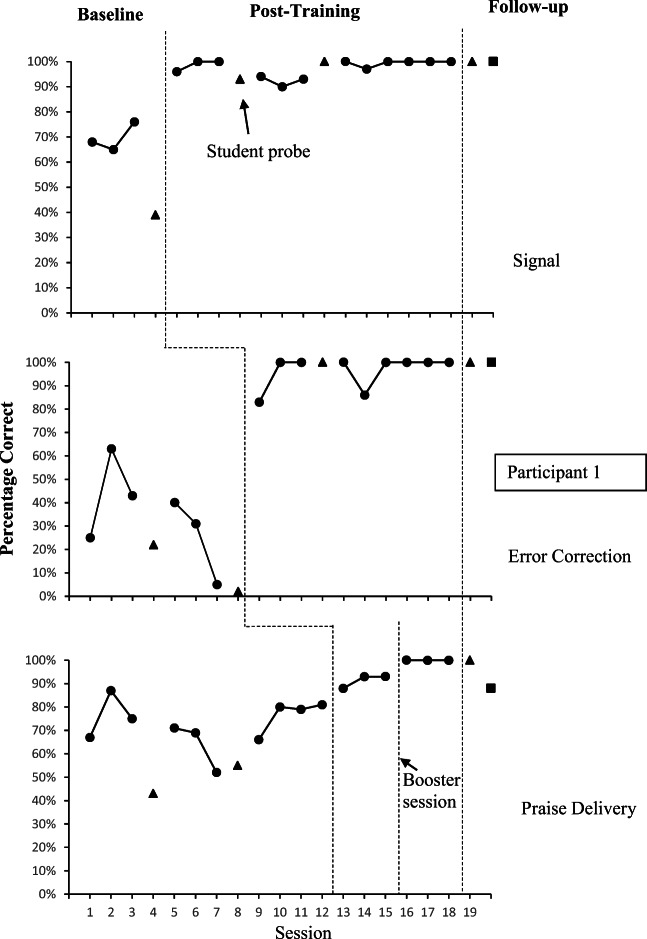

Figure 1 depicts the results for Participant 1. Participant 1’s, signal accuracy improved from an average of 62% in baseline to 98% following training. Participant 1’s performance quickly improved following training, and he demonstrated 93% correct responding during the probe with a student. Participant 1’s error correction accuracy improved from an average of 38% in baseline to 97% following training, and he met mastery after three sessions. During the student probe for error correction, Participant 1’s accuracy was 100%. Participant 1’s accuracy with the delivery of praise improved from an average of 68% in baseline to 96% following training. Participant 1 met mastery after three sessions; however, a booster session was provided in an attempt to further improve accuracy. Following the booster session, the participant was 100% accurate for the delivery of praise. A follow-up probe indicated Participant 1’s delivery of praise was 88% correct.

Fig. 1.

Percentage Correct Across Skills for Participant 1. Note. Solid triangles indicate student probes; squares indicate generalization probe

Figure 2 diplays Participant 2’s results. Participant 2’s delivery of praise improved from an average of 69% in baseline to 83% in the first three sessions following training. A booster session was provided, and Participant 2 met the criterion in three sessions. During the probe with a student, Participant 2’s responding was 100% accurate. Participant 2’s signal accuracy improved from an average of 31% in baseline to 99% following training. In Session 18, a student probe was conducted with Participant 2, and she was 100% accurate. Participant 2’s error correction accuracy improved from 44% in baseline to 93% following training. During follow-up probes, Participant 2 maintained 100% accuracy in signaling and delivery of praise, whereas error correction decreased to 79%.

Fig. 2.

Percentage Correct Across Skills for Participant 2. Note. Solid triangles indicate student probes

Social Validity

Table 1 depicts the questions and results of the social validity questionnaires. Both participants agreed that the procedures used were acceptable and effective in teaching them the three skills. Both reported that they believed the training would result in short- and long-term behavior change. Both also agreed that other staff would benefit from the training. The participants reported that they preferred this style of training and valued the immediacy of the feedback received during the training.

Discussion

The current study extends the use of BST to training instructors to implement DI lessons. Three key skills were identified and trained individually using BST. Both participants’ accurate performance of these skills improved quickly following BST. The efficacy of BST used to train a wide range of skills is well established; however, this is the first application of BST to train participants to implement DI. Although DI provides scripted lessons for the instructor to follow, there are critical skills the instructor needs to use along with the scripted lesson. For example, delivering praise immediately following correct responses is consistent with best instructional practices, but this cannot be scripted within a DI lesson, as the instructor’s response changes depending on the student’s response. Thus, BST may be a useful model for training staff to implement DI lessons.

During BST, the experimenter serving as the student had a script with predetermined correct and incorrect responses. This ensured that the participants encountered both correct and incorrect student responses and could practice responding accordingly. Alaimo et al. (2017) combined general-case training (GCT) with BST to examine if the BST and GCT package enhanced caregivers’ performance on a feeding intervention with their children. Their results indicated that following the BST and GCT package, the caregivers’ responses generalized across simulated behaviors to their children’s mealtime behaviors during posttraining. It is possible that systematically exposing caregivers to multiple potential child responses in simulation enhanced caregivers’ performance in the posttraining sessions. Similarly, both of our participants demonstrated generalization at or above the mastery criterion in the posttraining sessions in five of six evaluations, possibly because of the sampling of different correct and incorrect responses during training. Participant 2 also demonstrated generalization across different DI lessons in two of three evaluations. Thus, these findings are significant as they provide support for the use of BST to train teachers to implement DI, and suggest that BST may result in generalized responding for some teachers.

The social validity of the current procedures was also assessed, indicating that both participants’ acceptance of BST was high, and they rated their experiences with BST favorably. This finding is consistent with other researchers (Parsons et al., 2012) who have reported participants’ high acceptance of BST. It is possible that the participants’ acceptance was high because of the perception of the immediate and long-term value of the training or because of the use of positive feedback during BST (Parsons et al., 2012). Additional research is needed to determine why participants may rate BST highly in acceptance and whether that acceptance is associated with the continued application of the skills that were trained.

There were several limitations to this study. The BST package consisted of several components, making it impossible to know which training components or combination of components improved the participants’ performance. Participant 2’s student probe included the use of a different DI lesson from that which was used in training. Although this was necessary to avoid disrupting the student’s educational program, it is not clear whether the decreased performance with the error correction was a result of the change in materials or the application with a student. It is also possible that participants practiced procedures on their own between sessions or received feedback on performance from other sources (i.e., supervisors). In addition, both participants received prior training in DI and had a history of implementing DI in their current setting at the time of the study.

Future researchers may evaluate the use of BST with new staff members with no prior exposure to DI to determine whether BST results in the rapid acquisition of target skills. Researchers could also evaluate students’ performance to determine whether improvement in the teachers’ performance affects students’ responding. Researchers might also compare the maintenance of skills of participants who learn via BST with the maintenance of those who learn via traditional a lecture-style class. Last, because there are multiple components included in BST, researchers should conduct a component analysis to determine the necessary and sufficient components of BST required to produce generalized responding during DI lessons.

The current study demonstrates that BST can be used to teach staff to accurately implement DI. In settings where resources are limited and turnover of staff is higher, BST can be an effective option for programs or schools that need to quickly develop and maintain staff skills necessary to deliver DI to students.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Implications for Practice

This study

• extends the use of BST to the implementation of DI and

• demonstrates a procedure for using role-play scenarios within BST.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alaimo C, Severling L, Sarubbi J, Sturmey P. The effects of a behavioral skills training and general-case training package on caregiver implementation of a food selectivity intervention. Behavioral Interventions. 2017;33:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bin.1502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CS, Mellor JR, Rehfeldt RA. Implementing the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP): Teaching assessment techniques. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:36–47. doi: 10.1007/s40616-013-0004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, S., & Osborn, J. (2008). Language for learning. SRA McGraw-Hill.

- Homlitas, C., Rosales, R., & Candel, L. (2014). A further evaluation of behavior skills training for implementation of the picture exchange communication system. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 198–203. 10.1002/jaba.99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kubina RM, Commons ML, Heckard B. Using precision teaching with direct instruction in a summer school. Journal of Direct Instruction. 2009;9:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Loughrey, T. O., Contreras, B. P., Majdalany, L. M., Rudy, N., Sinn, S., Teague, P., Marshall, G., McGreevy, P., & Harvey, C. A. (2014). Caregivers as interventionists and trainers: Teaching mands to children with developmental disabilities. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 30(2), 128–140. 10.1007/s40616-014-0005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parsons MB, Rollyson JH, Reid DH. Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5:2–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldy, C. R., Rapp, J. T., & Capocasa, K. (2014). Training staff to implement brief stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 214–218. 10.1002/jaba.98. [DOI] [PubMed]