Abstract

In 2019, more than 25.9 million children under 18 were displaced due to unending political conflicts. Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) has a high level of empirical evidence to support its efficacy in processing trauma and behavioral problems in non-refugee children. Yet, little is known about its long-term effectiveness in refugee children. This study conducted a systematic review that assessed the evidence of the effectiveness of TF-CBT in reducing trauma symptoms among refugee children under 18 years of age. A systematic review was conducted from peer-reviewed literature databases (12 databases): PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT), Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PROSPERO, EBSCOHost, Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews, Social Sciences Index, and grey literature sources published from 1990 to 2019. The search yielded 1650 articles, and 4 peer reviewed studies were identified that met inclusion criteria and yielded a sample size of 64 refugee children from 21 different countries. All 4 studies provided evidence that supported TF-CBT’s effectiveness in decreasing trauma symptoms and sustainment during the follow-up assessment among refugee children participants. Despite TF-CBT effectiveness for trauma symptoms treatment, there is still limited evidence to suggest that TF-CBT is effective for all refugee children due to the pilot nature of the studies, and its underutilization in traumatized refugee children from different cultural backgrounds. Future studies should conduct more TF-CBT interventions with diverse refugee children to provide more empirical support for its effectiveness with that population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40653-021-00370-0.

Keywords: Refugee children, Trauma symptoms, Trauma focus cognitive therapy (TF-CBT)

Introduction

In 2019, more than 25.9 million children under 18 years of age globally were reportedly displaced due to increasing political conflicts, war, and genocide (UNHCR, 2019). Refugee children are vulnerable to traumatization due to exposure to stressful experiences they encountered during forced migration, persecution, flight, and resettlement (Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Carrion & Wong, 2012). In addition, refugee children encounter trauma and stress due to changes they experience in their family, community, and society which make them more vulnerable to a wide range of psychological problems (Vasserman, 2019; Tyrer & Fazel, 2014). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) diagnoses persist throughout a child’s life course and can reduce an individual’s quality of life if left untreated (Gadeberg et al., 2017). Researchers estimate that between 1% and 15% of children in the general population have experienced trauma and qualify for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Hamblen, n.d; Schottelkorb et al., 2012). Compared to the general population, 90% of refugee children experienced trauma, depression, and anxiety cases (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019; Thomsona et al., 2018; Alayarian, 2017; Kalt et al., 2013).

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) was developed as an evidence-based treatment approach and is based on traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for traumatized children. It is a flexible component-based treatment model made up of both individual and joint child and parent sessions (Cohen & Mannarino, 2015; Cohen et al., 2017). The acronym P.R.A.C.T.I.C.E summarizes the main components of TF-CBT: Psychoeducation, Parenting skills, Relaxation skills, Affective modulation skills, Cognitive coping skills, Trauma narrative, Cognitive processing of traumatic events, In vivo mastery of trauma reminders, Conjoint child-parent sessions, and Enhancing safety and future development trajectory (Cohen & Mannarino, 2015; also see Table 1). TF-CBT has been investigated with populations from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, with more than 20 randomized controlled trials supporting its efficacy and effectiveness (Goenjian et al., 1997; Palic & Elklit, 2011) in helping children to process their trauma and overcome emotional and behavioral problems (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019; Cohen & Mannarino, 2015; Murray et al., 2013). International guidelines recommend TF-CBT as a first-line treatment for traumatized children and youth due to its cultural sensitivity approach (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2012). Although studies have reported the effectiveness of TF-CBT to reduce trauma in children, few empirical studies have tested its effectiveness in the refugee population (Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016).

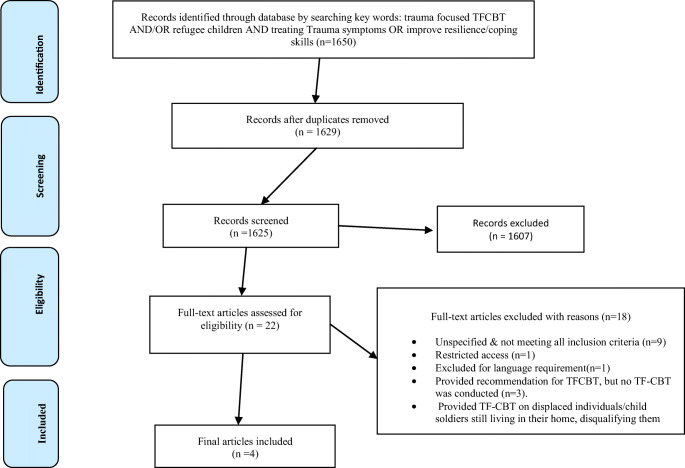

Fig. 1.

Flow of information through the phases of systematic review

Table 1.

TF-CBT “P.R.A.C.T.I.C.E” Sessions according to Cohen et al., 2006

| Session | Description & Practice |

|---|---|

| 1 | Psychoeducation, Parenting skills: |

| Psychoeducation about trauma, trauma-related symptoms and the rationale of TF-CBT, normalizing the symptoms, teaching positive parenting skills e.g., praise, active ignoring, contingency management strategies) | |

| 2 | Relaxation: |

| Information about the rationale of relaxation, demonstration and practicing relaxation techniques (progressive muscle relaxation, and/or controlled breathing). | |

| 3 | Affective modulation: |

| Explanation of rationale, identification of feelings, expression of feelings, rating the intensity level of emotions, positive self-instructions, coping with difficult/ unpleasant emotions, thought stopping, teaching problem-solving strategies. | |

| 4 | Cognitive processing, I: |

| Outline the cognitive triangle, identify dysfunctional thoughts in daily life, help the child generate more accurate and helpful thoughts. | |

| 5–8 | Trauma narrative |

| Decide on a format for the narrative, describe the perception of event including the worst moment, read the narrative, add thoughts and feelings. | |

| 9 | Cognitive processing II: |

| Exploring and correcting cognitive errors concerning the traumatic experience (e.g., cognitions of guilt). | |

| 10 | In vivo exposure: |

| Explaining the rationale, development of a “plan” (if necessary, instruct caregiver for co-therapeutic expo) | |

| 11 | Conjoint child/caregiver session: |

| Explaining the rationale, prepare child and parent for conjoint session, sharing the trauma narrative, answering questions, increase communication. | |

| 12 | Enhancing safety and future skills: |

| Developing a feeling of safety, a safety plan, teaching safety skills. |

Adapted from: Cohen, J. A, Mannarino, A. P, & Deblinger, E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents New York: Guildford Press

Most recently, many researchers in the United Stated have embarked on numerous research projects that focuses on prevention and interventions and developing resources to assist refugees’ families (Trauma and Community Resilience Center, 2020; Bridging Refugee Youth & Children’s Services, 2020; Women’s Refugee Commission, 2020; Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights, 2020). However, the majority of the programs only provides immediate needs such as food, shelter and other necessities even though trauma is the largest reported mental health issue among the refugees, who are as diverse in their mental health needs as any other population (Anani, 2013; Hilado & Lundy, 2018). There are clearly few evidence-based interventions, and TF-CBT is one of the interventions that needs further investigation to determine its effectiveness on the post resettlement care of refugee children and other displaced persons coming from non-Western countries (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There has been a consensus among researchers that refugee children require particular assistance, but several obstacles hamper the delivery of psycho-social support (Nocon et al., 2017). Some barriers include the fact that refugees often have insufficient knowledge about how to access mental healthcare, fear of stigmatization, different understanding of the concepts of mental health problems and their treatment, and that the host nation often limits access to the healthcare system (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019). Refugee families may also be reluctant to seek mental health support due to stress they might have experienced in settling into a new country (World Health Organization, 2018). These challenges set refugee children apart from the mainstream community and stifle their overall adjustment and development.

The current geopolitical developments and worldwide migration crises stress the urgency of providing effective treatment to trauma exposed refugee children (Lely et al., 2019; Palic and Elklit, 2011). Debates continue in the literature over whether specific TF-CBT interventions are needed to reduce trauma in refugee children (Gerger et al., 2014). These debates postulate that the severity of trauma symptoms among refugee children require serious attention to identify a trauma-focus intervention that might be essential to alleviate trauma symptoms before they spiral into other problems such as depression, substance abuse, and suicidal feelings. TF-CBT has a higher level of caregiver involvement suited to improving social networks, support systems, and resources that refugee children often lack (Murray et al., 2013; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019). Due to successes in utilizing TF-CBT in studies with non-refugee populations, TF-CBT may be recommended to produce intended results in treating refugee children with many trauma-related symptoms (Palic & Elklit, 2011).

As the number of refugees worldwide continues to increase, determining the effectiveness of established methods of TF-CBT for refugee children is crucial. The concept of psychotherapy and motivation differs across cultures, and there is no clear-cut recommendation on whether Western, evidence-based TF-CBT is effective and applicable to refugee children (Nocon et al., 2017). Since TF-CBT has been established to support vulnerable children’s mental health needs across all cultures (Cohen & Mannarino, 2008), there is a high need within this population for this intervention to allow refugee children to receive the help they so desperately need to cope with their trauma (Marshall et al., 2016). This systematic review was conducted to answer the following question: Is Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) effective in reducing trauma symptoms in refugee children under 18 years of age? To answer this question, a rigorous systematic review of peer-reviewed literature was conducted.

Importance of TF-CBT to Social Work Practice

Children’s well-being has long been a subject of concern in social work (Kamerman & Gatenio-Gabel, 2014; National Association of Social Workers, 2005), and ensuring healthy development for all children through access to mental health services is one of the social work’s greatest challenges (Grand Challenges for Social Work, 2018) including other mental health related fields. Refugee children have been recognized as a vulnerable population in need of trauma-focused interventions and effective service provision, particularly for those who have experienced severe trauma before leaving their country of origin (Lustig et al., 2004).

Throughout history, social work has been dedicated to promoting the dignity and worth of all humans regardless of their nationality, race, ethnicity, religion, or differing cultural backgrounds. Refugee children who are confronted with many traumatic experiences (Ehntholt & Yule, 2006) can potentially benefit from TF-CBT. A specific function of TF-CBT prepares social workers with skills needed to restore a healthy level of self-respect by promoting unconditional self-acceptance regardless of the condition afflicting the refugee children, at the same time helping them acknowledge and accept their strength and deficits resulting from trauma (González-Prendes, 2012). Social workers frequently meet refugee children with adverse history of trauma during their professional lives. TF-CBT is an alternative intervention to supplement care by which social workers may have an opportunity to view a child’s symptoms of maladaptive coping and understand how early trauma shapes psychosocial functioning across the lifespan. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013), traumas involving early childhood maltreatment and family dysfunction are especially prevalent and impactful. Thus, it is important to increase the levels of support that refugee children may need through trauma-focused interventions such as TF-CBT.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

According to the United Nations Refugee treaty, a refugee is defined as “a person who owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or owing to such, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country” (Hilado & Lundy, 2018, p.25; U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2008). Although there are essential distinctions between who is a refugee, migrant, resettled refugee, and asylum seeker, this researcher sought to keep inclusion criteria quite broad since these terms are often used interchangeably. The following selection criteria were employed during the review process;

Participants: refugee children under 18 years with exposure to war-related trauma and other forms of trauma, and must reside in another country in any part of the world. This study excluded child soldiers, internally displaced persons, and other non-refugee children who did not fall under the definition of a refugee.

Language: This review included all the studies that were only written in English. This was done in order to make it easier for this researcher to understand the study process, how the study was conducted, ensure rigorous assessment, avoiding biases, and inaccurate interpretation. All studies that were written in other languages were excluded for a final review because that would have demanded involving translators to facilitate communication in order to capture the essence of the study.

Intervention: This review only included studies that conducted TF-CBT or offered in combination with other interventions with the primary emphasis on reducing trauma symptoms on refugee children. All studies that did not meet this eligibility criteria were excluded because the overall aim of this study was to examine TF-CBT itself because of its emphasis on treating children’s trauma.

Outcomes: This review included all the TF-CBT studies that focused on a wide range of PTSD diagnosis and symptoms of PTSD or trauma, general distress as measured by other forms of instruments in all refugee children. Phrases such as trauma, post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) were used interchangeably.

Study designs: Since this review was intervention based, all the randomized controlled trials (RCT), uncontrolled pilot studies as well as single case designs were included in the in this study.

Type of study: This review aimed to include all relevant studies regardless of their publication status to avoid publication bias. Unpublished and ongoing studies were included. However, conference abstracts were excluded due to the limited information they present, which in turn could make it difficult to carry out a rigorous assessment needed to answer the research question proposed in this study.

More detailed information on the inclusion and exclusion are provided in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Literature Search Strategies

This review adapted Cochrane and Campbell Collaboration guidelines (Boland et al., 2017). Campbell and Cochrane require all the reviews must include a systematic search for unpublished reports to avoid publication bias, study inclusion and coding decisions are carried out by at least two reviewers who work independently and compare results, conduct rigorous methods to synthesize evidence, including an appraisal of study quality were appropriate, statistical meta-analysis of quantitative evidence, and theory-based analysis of qualitative evidence are also included (Campbell Collaboration, 2019; Cochrane Community, 2018). This researcher searched for published and unpublished studies written between 1990 to 2019 that examined the effectiveness of TF-CBT on refugee children from around the world. This timeframe (1990–2019) was employed because TF-CBT was initially developed in 1990 as a conjoint parent-child treatment by Cohen, Mannarino, and Deblinger that uses cognitive-behavioral principles and exposure techniques to prevent and treat posttraumatic stress, depression, and behavioral problems (Cohen et al., 2006). Thus, the search could not have permitted this researcher to go beyond the initial development of the intervention.

This researcher culled all the literature from twelve electronic databases that were systematically searched: PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT), Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Web of Science, PROSPERO, EBSCOHost, Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews, and Social Sciences Index. These were searched in order to find the studies that could help to answer the research question (Boland et al., 2017). Additionally, grey literature was searched that included dissertations/thesis, government databases, bulletins, and annual reports to access diverse sources and ongoing unpublished studies. According to Bogdanski and Chang (2005), the term “grey literature” in a traditional systematic review simply means unpublished research, and the term first came into use in the 1970s. The initial search started on August 30th, 2019 and was completed on October 2nd, 2019.

This review employed a Boolean search strategy to access the studies that met the eligibility criteria. A Boolean strategy allows the user to combine or limit words and phrases in an online database search to retrieve relevant results. Using the Boolean terms: AND, OR, NOT, the searcher can define relationships among concepts (Boland et al., 2017). This researcher applied Boolean strategy by combining keywords related to the research question, such as, “refugee children AND war-affected children OR displaced persons”, “trauma symptoms AND post-traumatic stress disorder AND/OR distress, “efficacy AND/OR effectiveness, treatment/therapy outcomes OR intervention OR treatment AND/OR “Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy”, and “reduce AND/OR decrease trauma symptoms”. The searches were limited to refugee children under 18 years and other eligibility criteria, and adaptations to the search terms were made in accordance with the requirements or truncation of each respective database.

Data Collection

The initial search strategies employed resulted in a large number of identified peer-reviewed literature (n = 1650) which were later screened, and relevant titles and abstracts were obtained from both published and grey literature. During the first phase, literature reference lists and the authors of significant articles were checked. There were 1629 citations after duplicates were removed. The second phase included a careful screening of abstracts to ensure that none of the important studies were excluded from the final review bringing the records to 1625 citations. A third-round involved screening for specific abstracts and titles that had TF-CBT conducted on refuge children or other children, and this rigorous assessment took this researcher one month to complete. One thousand six hundred and seven (n = 1607) articles were excluded based on a thorough review of titles and abstracts. A total of twenty-two (n = 22) articles were included for a full-text review. Finally, only 4 full-text articles met the full inclusion criteria. RefWorks, a bibliographic software (Boland et al., 2017), was utilized to save, store, and sort out all the citations and references obtained from the studies. Bibliographies of relevant studies were reviewed, and full-text articles were read for data analysis. Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) flow diagram (Boland et al., 2017) was used as a study selection process to detect any psychosocial intervention for refugee children. The specific search strategies applied to each database are detailed in PRISMA Flow Diagram above (see Fig. 1).

Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

After the twenty-two full-text studies were identified from various sources and reviewed, the eligibility criteria were applied to them. A systematic review of the quality of rating scales (Boland et al., 2017), Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was chosen to evaluate the quality of the twenty-two selected peer-reviewed studies (CASP, 2018). CASP checklist is a reliable tool designed to be used for systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case studies, diagnostic studies, qualitative studies, and clinical predictions (CASP, 2018). In the CASP scale, the evaluation of the quality of design and methods include the population studied, intervention provided, study design, outcome, rigor of the study, and the study’s results, and the questions have three choices (Yes, No, and Can’t tell). The final twenty-two selected studies were reviewed against criteria laid out in critical appraisal checklists for TF-CBT evaluations.

Although Campbell and Cochrane Collaboration (2018) requires that study inclusion and coding decisions are carried out by at least two reviewers who work independently and compare results, this researcher did not involve other colleagues. This was because this study was carried out as an independent assignment required for the fulfillment of doctoral degree coursework in social work at the University of Alabama. However, this researcher still carried out multiple assessments to ensure rigorous review to minimize biases. One of the issues that arise in a systematic review is bias (Millard & Flach, 2016), especially if only one person is involved. This researcher minimized selection bias by using CASP checklist, and the adoption of stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria to improve the homogeneity of the intervention on refugee children. After each review was conducted on all twenty-two studies, this researcher included four studies that fully met the inclusion criteria that were considered to be of high quality based on CASP checklist. In addition, after full-text review, eighteen studies were excluded based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Some of the reasons for exclusion were based on not meeting the language requirement, TF-CBT was not provided on refugee children, but on internally displaced, child soldiers who did not fall under the specified refugee status definition etc. For a full description please see the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Results

This review’s final sample size included four high-quality studies that met inclusion criteria and were published between 2012 and 2019 [see Fig. 1]. Although the majority of the studies (n = 18) were of high quality, they were excluded from the initial screening because they did not meet the stipulated eligibility criteria required for TF-CBT in refugee children, instead conducted TF-CBT on internally displaced persons, child soldiers, formerly displaced individuals, on children with trauma still living within their native countries, and non-refugee children, therefore, were not adherent to the inclusion criteria. In assessing the overall quality of design and methods in the studies, all four studies were considered appropriate using CASP. The studies were conducted in two countries: one in the United States and three in Germany. Recruitment procedures differed across all the studies: participants in three studies in Germany were referred by social workers to the outpatient clinic (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015; Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019; Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016), whereas participants in the USA-based study were recruited from the schools where refugee children attended (Schottelkorb et al., 2012). All the participants were recruited based on their status as refugee children and meeting the criteria of trauma symptoms measured by the score on one of the trauma screening tools that was utilized at baseline, posttest, and follow-up sessions (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Summary of included studies

| Author(s) | Setting(s) | Disorder(s) | Country(s) of the study | Intervention Focus/Type | Screening Tool(s) | Study Design(s) | Participants countries of origin(s) | Sample Size(s) | Age(s) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schottelkorb et al. (2012) | School | TS | United States | TFCBT & CCPT | UCLA PTSD & PROPS | RCT | Burundi, Kenya, Liberia, Rwanda, Somalia, Tanzania, Burma, Nepal, Russia, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey& Uzbekistan | 31 | 6–13 | TF-CBT was effective in decreasing trauma symptoms from baseline assessment to follow up according to child and parent reports (p < .03). |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2015). | Outpatient Clinic | PTSS | Germany | TF-CBT | CAPS-CA or PDS | RCT | Somalia, Iran & Afghanistan | 6 | 17–18 | Children reported moderate to high levels of PTSS at baseline and a clinically significant decrease in symptoms at posttest. On individual level, percentage improvement was >50%, and clinically meaningful changes was observed in 100% of the TF-CBT group. |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner (2016). | Outpatient Clinic | PTSD | Germany | TF-CBT |

CAPS-CA UCLA-PTSD, & SCARED |

SCD | East Africa (Country unspecified) | 1 | 17 | Trauma symptoms decreased in a clinically significant at the end of the treatment. The percentage of improvement was more than 50% for all measures for self-report at the follow up. |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2019) | Outpatient Clinic | PTSD | Germany | TF-CBT | Kinder-DIPS, CATS, MFQ, SDQ, A-DES, PHQ-15 & SCARED | UPS | Afghan, Eritrea, Gambia, Iran, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan & Syria. | 26 | 15–19 | At post-intervention, participants (n = 19) showed significantly decreased PTSD symptoms (p = .003) with large effect size (d = 1.08). Improvements remained stable after 6 weeks and 4 months follow up. In addition to PTSD symptoms, their caregivers reported significantly decreased depressive and behavioral symptoms in participants. According to the clinical interview, 84% of PTSD cases recovered after TF-CBT treatment. |

PROPS- Parent Report of Posttraumatic Symptoms, CAPS-CA -Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents, UCLA-PTSD- The University of California Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index, SCARED- Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders, CATS- Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen, SDQ- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, PHQ-15- The Patient Health Questionnaire Physical Symptoms, Kinder-DIPS- The Diagnostic Interview for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, A-DES -Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale, MFQ -The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, PDS -Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, RCT -Randomized Control Trials, CCPT- Client Centered Play Therapy, SCD- Single Case Design, TS- Trauma Symptoms, UPS -Uncontrolled Pilot Study

Table 3.

Trauma symptom measures and symptom reductions of TF-CBT Intervention in refugee children

| Author(s) | Measures | Baseline | Posttest | FU | Improvement(s) or Changes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schottelkorb et al. (2012) | N | M | N | M | |||

| UCLA PTSD (child) | 14 | 25.04 | 14 | 20.29 | – | – | |

| PROPS (Parents) | 8 | 20.04 | 8 | 16.92 | – | – | |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2019) | MFQ proxy | 19 | 13.32 | 18 | 5.63 | 6.17 | – |

| SDQ self | 18 | 13.72 | 17 | 10.28 | 11.76 | – | |

| SDQ proxy | 18 | 16.67 | 17 | 9.94 | 9.94 | – | |

| PHQ-15 | 16 | 9.06 | 15 | 6.56 | 7.53 | – | |

| CATS self | 19 | 30.58 | 17 | 20.16 | 20.35 | 17.86 | |

| CATS proxy | 19 | 33.16 | 17 | 17.53 | 17.06 | 17.00 | |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2015) | N | Md | N | M | FU | ||

| CAPS-CA | 4 | 52 | 4 | 14.5 | – | 73.5% | |

| PDS | 2 | 32 | 2 | 12 | – | 63% | |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner (2016) | N | Baseline score | N | Posttest score | 6 months FU | ||

| CAPS-CA | 1 | 50 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 89% | |

| UCLA-PTSD | |||||||

| Self | 1 | 37 | 1 | 20 | 6 | 64.5% | |

| Caregiver | 1 | 43 | 1 | 18 | 36 | 37% | |

| CDI | |||||||

| Self | 1 | 21 | 1 | 16 | 7 | 45.5% | |

| SCARED | |||||||

| Self | 1 | 24 | 1 | 17 | 6 | 52% | |

| Caregiver | 1 | 41 | 1 | 29 | 24 | 35% | |

PROPS- Parent Report of Posttraumatic Symptoms, CAPS-CA- Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents, UCLA-PTSD- The University of California Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index, SCARED- Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders, CATS- Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen, SDQ- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, PHQ-15- The Patient Health Questionnaire Physical Symptoms, Kinder-DIPS- The Diagnostic Interview for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, A-DES- Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale, MFQ- The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, PDS- Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, M (means of symptoms reductions), MD (medians of symptoms reductions), FU (Follow up), Proxy (instruments administered either to caregivers or parents to measure children’s trauma symptoms)

The total sample size yielded sixty-four refugee children between six to eighteen years old. The majority of the studies’ sample sizes were relatively small, with the lowest being one and the highest being thirty-one. Out of the four studies, two studies were randomized control trials (RCT), the third was an uncontrolled pilot study, and the last was a single case study performed on a girl from East Africa. All three German-based studies were conducted in an outpatient setting, while the United States-based study was conducted in a school setting. Participants in all four studies originated from twenty-one different countries that included Burundi, Kenya, Liberia, Rwanda, Somalia, Tanzania, Burma, Nepal, Russia, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Eritrea, Gambia, Iran, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, and Syria. Although the participants were drawn from many parts of the world, boys were overrepresented in the studies. Regarding nationality, in the United States-based study, more than two-thirds (67.7%) were from Africa (Burundi, Congo, Kenya, Liberia, Rwanda, Somalia, and Tanzania), whereas in all the three German-based studies, Afghan refugee children (32%) were significantly overrepresented when compared to the total sample size. In all four studies phrases such as trauma symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) were used interchangeably but had the same meaning in terms of their applications (see Table 2).

All the sixty-four refugee children who met the criteria for trauma symptoms participated in TF-CBT sessions that includes eight components subsumed within the PRACTICE acronym: psychoeducation and parenting skills, relaxation, affective modulation, cognitive processing I, trauma narrative, cognitive processing II, in vivo exposure, conjoint/caregiver session, and enhancing safety and future skills (Cohen et al., 2006). The range of children’s TF-CBT sessions were between 12 to 28 and lasted between 60 to 100 min. While the TF-CBT manual requires caregiver involvement in line with the treatment manual (Cohen et al., 2006), most of the sessions were conducted with minimal caregiver involvement. The caregiver sessions varied between 3 to 23 sessions depending on the need or seriousness of the case. In all four studies, the TF-CBT session addressed a wide range of trauma symptoms experienced by refugee children from different cultural backgrounds, experiences, ages, and nationalities. Contents according to the TF-CBT manual are described in Table 1.

The majority of the studies—three out of four— used professional interpreters during the TF-CBT sessions when the therapist met with caregivers or refugee children who demonstrated limited language proficiency. Across the four studies, twenty-one professionals with varying levels of education were involved in conducting TF-CBT, including doctoral-level licensed counselors, counselor educators, trained TF-CBT therapists, and master’s level counseling students. Three studies involved TF-CBT sessions which were conducted in German, and the remaining study utilized English during sessions. During the sessions, the German and English languages were appropriate for use in the studies because they are official languages spoken in the countries where the studies were conducted, Germany and the United States. In all the four studies, a fidelity check was monitored through many forms that included videotaped sessions that the supervisors watched, case conference calls by experienced TF-CBT trainers, and blinded rater assessed TF-CBT during baseline, posttest, and follow up sessions to ensure TF-CBT manual fidelity. Across all four studies, fifty-five out of sixty-four refugee children completed all of the TF-CBT sessions (86%), and the overall attrition was very low; only nine out of sixty-four dropped out of the treatment sessions (14%), and most of the dropouts occurred during the baseline (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Shows the results of TF-CBT sessions, parental/caregiver, interpreters and professional involvement, fidelity and completion/attrition rates

| Author(s) | TF-CBT sessions | Parental/caregiver Involvement | Interpreters Involvement | Professional Involvement | Fidelity check | Completion/Attrition rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schottelkorb et al. (2012) | Between 12 to 20 sessions lasting approximately 60 to 90 min | Parents/caregivers were not involved due to difficulties associated with getting parents and caregivers and interpreters commit to the 90 min sessions | Interpreters were used to administer the screening tools. Also, interpreters were used when the therapist met with parents if needed | TF-CBT therapists were involved. These included doctoral level licensed professional counselor, counselor educators and certified TF-CBT therapist and master’s level students (n = 9) | Fidelity to TF-CBT modality was closely monitored through the videotaped sessions that the supervisors watched. | Of the 31 participants, 26 (83.9%) completed the follow up assessment. |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2015) | Between 12 to 28 treatment sessions lasting approximately 100 min. | Between 3 to 23 sessions were dedicated to caregivers (M = 9.8) | Professional interpreters were involved (n = 2) | Therapists trained in CBT and TF-CBT with the help of professional translators conducted the session (n = 3). |

Case conference calls were offered twice a week a month by one of the developers of TF-CBT (Anthony Mannarino) and one experienced TF-CBT trainer (Laura Murray) to ensure manual fidelity. Trained blinded psychologists performed the assessment. |

All participants completed the treatment (100%). |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner (2016) | 12 sessions of TF-CBT were conducted for a refugee girl from East Africa | The caregiver was involved in 12 sessions of TF-CBT. | No interpreters were involved during the treatment session. Both the girl and the caregiver demonstrated language proficiency sufficient for participating in psychotherapy | A trained psychotherapist trained in TF-CBT conducted the sessions (n = 1) | The blind trained raters blind to treatment condition administered the measures at pre, post & 6 months follow up. | A girl completed the treatment sessions (100%). |

| Unterhitzenberger et al. (2019) | 15 mean sessions of TF-CBT were conducted lasting 100 min each. |

The level of caregivers’ involvement was flexible & modified to the individual participant’s needs. Therapist saw the caregiver in 8 sessions (53.3% of the participants’ sessions). |

Interpreters were made available when needed. Interpreter was presented 55% of the time during the treatment and fidelity checks. | German based licensed psychotherapists who were also trained in TF-CBT conducted the sessions (n = 8). | Treatment fidelity was checked by involving different raters for each assessment (baseline, post-intervention, 6 weeks follow up and 6 months follow up. Raters randomly viewed 3 videotaped sessions of each participant. | Treatment was completed by 22 out of 26 participants i.e., the dropout rate was 15.4%. The completion rate was 84.6%. |

Furthermore, before the TF-CBT interventions (baseline), all four studies reported a significant increase of trauma symptoms that include difficulty concentrating, mood swings, irritability, guilt, shame, withdrawing from others, feeling disconnected or numb, and many others. Eleven screening tools were administered in total across all four studies in order to measure trauma symptoms in refugee children. Trauma symptoms were assessed either by children’s self-report or parents’ reports based on one of the instruments indicated in Tables 2 and 3. All the instruments administered were found to be clinically reliable and valid, and have been used in the past in clinical studies that involved TF-CBT or similar intervention work with children from different cultural backgrounds, both in the United States and other parts of the world (Cohen et al., 2006). On the posttest, refugee children reported a clinically significant reduction in trauma symptoms after receiving TF-CBT and remained stable at the follow up sessions. Based on the self-reports of refugee children on different trauma screening tools that were used to measure trauma, the overall rates of improvement among those who participated in TF-CBT ranged from 45.5% to 89% at posttest and follow-up sessions. The overall mean of improvement based on all measures combined was calculated at 13.9 at posttest based on refugee children’s self-reports. Additionally, the overall mean of improvement based on caregivers’ reports estimates was calculated at 14.7. A detailed description of trauma symptom reductions during baseline, post-intervention, and follow up sessions are included in the meta-analysis (see Table 3).

Discussion

This manuscript used a systematic review methodology to evaluate the effectiveness of evidence-based TF-CBT in decreasing trauma symptoms from four study samples of traumatized refugee children. The studies tested the feasibility of TF-CBT in a small sample of traumatized refugee children (n = 64), a vulnerable group who have been undersupplied with mental health support (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015). All of the four studies reviewed reported that refugee children exhibited high levels of trauma at the beginning of the treatment and reported a significant decrease of trauma symptoms at the end of the treatment and during follow ups. The findings of this review provide evidence that is consistent with prior findings stating that TF-CBT can be highly effective in treating trauma symptoms in children from other cultures (Bass et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2006; Eberle-Sejari et al., 2015; Goenjian et al., 1997; Murray & Skavenski, 2012; Palic & Elklit, 2011), including refugee children who have encountered multiple traumatic experiences in their lives. Additionally, TF-CBT is not only the most strongly supported intervention used in high-income countries for trauma treatment in children (Cary & McMillen, 2012; Jensen et al., 2014), but also has proven feasibility for use with children from different international settings, such as Zambia and Cambodia (Murray et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2008). Despite this, many clinicians in western countries are still uncertain about using manualized therapies for young refugees (Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016). It has been suggested that TF-CBT can only be appropriate for use with traumatized refugee children if an adjustment to the treatment protocol is made to account for the unique features of refugee trauma (National Child Stress Network Refugee Task Force [NCTSNRTTF], 2005). Unfortunately, most of the features of TF-CBT do not necessary account for the associated cultural values, and this may be challenging for some refugee children and caregivers to participate in TF-CBT due to differing views of what constitute trauma.

Although the studies point out that TF-CBT is highly effective, it is also difficult to state any conclusions for the whole population of refugee children, as this population is constituted by individuals of many different nationalities, languages, ages, genders, religions, diverse cultures, and experiences. Also, mental health professionals have rarely used evidence-based TF-CBT with refugee children (Unterhitzenberger & Rosner, 2016). In this regard, it is crucial to utilize TF-CBT more rigorously in controlled randomized studies in order to increase its empirical support with vulnerable refugee children and their caregivers. Albeit, mental health professionals should not hold back from providing treatment to refugee children, even with manualized approaches as suggested by treatment guidelines, especially if they are phase-based and culturally sensitive, as is TF-CBT (Cohen et al., 2006). At this time, it remains that TF-CBT is among the few treatments considered well established for children exposed to trauma (Schottelkorb et al., 2012; Silverman et al., 2008). Although more rigorous empirical trials are needed on testing TF-CBT on refugee children, we could only predict that the outcome on reducing trauma symptoms may not differ significantly from other children with similar traumatic experiences.

While TF-CBT is frequently conducted with parents or caregivers in an equal number of sessions with children (Cohen et al., 2006), this review found minimal caregiver involvement during the TF-CBT sessions. Despite minimal caregiver involvement, this review’s findings are consistent with previous meta-analysis studies that indicated that low levels of parental or caregiver involvement in TF-CBT is as effective as or less than child only treatment for reducing posttraumatic stress in children (Bass et al., 2011; Lang et al., 2010; Silverman et al., 2008). However, other studies argued that involving caregivers in trauma-focused treatments for children shows better treatment outcomes than those without parental involvement (Yasinski et al., 2016). Hence, this may indicate that having both refugee children and their caregivers involved in the treatment process may have advantages and disadvantages worth paying attention to. The benefits of the presence of the caregivers during the sessions may help the clinicians to understand the child’s trauma better or resolve issues conjointly with the caregiver, strengthen the treatment outcomes, and allow caregivers to learn trauma coping skills, and how to help their children when retraumatization occurs. A potential challenge associated with the caregiver’s presence likely would be that a child may not disclose some of the major problems that may directly involve the caregiver during the treatment session.

Furthermore, mental health clinicians can fully adopt TF-CBT to treat trauma for thousands of displaced refugee children, enhance their psychological wellbeing, and advocate for the appropriate care they need most. TF-CBT’s success is noteworthy given that the majority of refugee children will likely spend their entire lives in the host country; it may be essential to include culturally oriented TF-CBT, which is compatible with the refugee child’s culture. Folkes (2002) stated that refugee children arriving in a new country, either with or without their families, are likely to benefit from TF-CBT to enable them to settle in their new environment. For those arriving in high-income countries, accessing services can be fraught with difficulties due to linguistic, social, and historical reasons. More so, previous war and conflict experienced by children disrupt social, educational, and economic systems and psychological wellbeing in complex ways in refugee children. These disruptions disproportionately affect refugee children and their transitions into adult life (Viner et al., 2012). Thus, refugee children with higher levels of trauma may benefit from TF-CBT needed to promote their wellbeing and improve the positive relationship with family, peer, and educational domains that are crucial to help them fulfill their potential wellbeing and development.

This review revealed that most of the TF-CBT sessions conducted in the studies were between 12 to 28 week sessions. Concerning cost-effectiveness and immediate trauma symptom improvements, short TF-CBT focusing on traumatic stress symptoms may be sufficient for refugee children whose basic needs are already met. However, for refugee children with multiple traumatic experiences, longer sessions may also be the feasible option to allow time for healing to occur while giving children the maximum time of the TF-CBT sessions. The studies in this review ensured the involvement of the professionals not only trained in TF-CBT, but also holding other important credentials in mental health profession. TF-CBT treatment manual recommends clinicians who provide TF-CBT to have extensive training and supervised experience in child development, have experience in assessing and treating a wide range of psychiatric disorders, and have training and supervision in providing a variety of child and family treatment (Cohen et al., 2006). Cohen et al. (2006) further recommend clinicians to attend one to three day training workshops by qualified TF-CBT trainers or participate in the online TF-CBT training and ongoing expert consultation. Thus, considering the vulnerability of refugee children with insurmountable traumatic experiences, involving personnel with the right skills and knowledge can potentially help to implement TF-CBT with maximum success and help children to gain essential positive coping skills needed to overcome their trauma.

Furthermore, this review indicates that interpreters were involved during the TF-CBT sessions as needed. TF-CBT is a robust and culturally sensitive treatment that considers the needs of refugees with limited language skills (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2019). Professional interpreters trained in TF-CBT must be fully involved to alleviate communication barriers created by some of the phrases, concepts, statements or technical terms used during therapeutic sessions. The TF-CBT trained interpreters can help the therapist learn more relevant information that impacts refugee children’s culture-related emotional responses (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015), avoid the tendency to “filter” information, and may demonstrate the level of cultural competence, experience working with a person of the other culture, demonstrate ability to sort out personal biases related to the different cultures, and comfort with ambiguous situations (Marcos, 1979). Marcos (1979) discussed several ways interpreters can distort interpretation in clinically significant ways if not properly trained. Marcos identifies three primary sources of distortion: 1) deficient linguistic or interpreting skills, 2) lack of therapy using interpreters and sophistication in mental health, and 3) interpreter attitudes toward either the client or the clinicians. Thus, trained and experienced professional interpreters are essential to improve professionalism in the delivery of TF-CBT, prevent negligible miscommunication, misunderstanding, and loss of information on how trauma is conceptualized in the specific refugee groups during the TF-CBT implementations.

Finally, in this review, attrition rates were relatively lower than expected, considering that refugee children may have different views of trauma and may not be familiar with manualized treatments. Although the previous study indicated that refugees might not understand the concept of TF-CBT (Kinzie et al., 2006), this study’s findings may suggest that the caregivers and refugee children found TF-CBT relevant or beneficial to them in many ways. The increased completion rates may indicate that children and their caregivers developed a good therapeutic relationship with the therapists, leading to success in reducing trauma symptoms at posttest and follow-up sessions. There is also the possibility that the attrition may have occurred because refugee children moved to another place or may not have found TF-CBT culturally appropriate for them.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

Although this review adds to the body of literature by demonstrating the effectiveness of TF-CBT in reducing trauma symptoms in refugee children, there are several limitations worth highlighting. All studies were required to be written in English, further limiting the scope of the review. This led to the exclusion of one study written in German, which met all other criteria and therefore could have contributed to the body of knowledge in this review (Bohnacker & Goldbeck, 2017). The sample size of this review was relatively small, limiting further generalization to other refugee children. African refugee children were overrepresented in the study located in The United States, and Afghan refugee children were overrepresented in the German studies, while other nationalities were under represented in all four studies. Hence, studies of this type hardly represent the heterogeneity of the group of refugee children who vary from culture to culture. In this review, we cannot rule out the possibility that simply having regular appointments with a professional could account for a reduction of symptoms in refugee children (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015). Just like in any other therapy, we cannot be sure whether the intervention helped to reduce the trauma symptoms experienced by refugee children. Although two of the four studies followed a randomized controlled design, there was no mention of how many refugee children were assigned to the control group, and it is unclear how the decrease in symptom severity would have compared with refugee children receiving no intervention. Therefore, the results of this review’s studies cannot provide a general conclusion about comparisons to alternative interventions. During baselines and posttest treatment sessions, there is also a possibility that interpreters without TF-CBT knowledge who assisted with communication could have led to some loss of information and misunderstandings due to limited English proficiency and could have helped therapists understand some cultural characteristics and build a bridge for culturally sensitive therapeutic work.

Additionally, this study also demonstrated some strengths. Across the four studies, rigorous fidelity checks were reported, making it easier to investigate whether therapists properly implemented and adhered to components appropriate for TF-CBT manualized treatment. Another strength was the use of trained professionals in TF-CBT who possessed knowledge and experience in mental health service delivery. This resulted in implementing TF-CBT that culminated in the success of reducing trauma symptoms in the refugee children.

Implications for Social Work Practice & Research

Future studies should include larger sample sizes consisting of a more diverse population of refugee children in order to replicate the findings of the TF-CBT studies. TF-CBT studies should consist of a wait-list control group with a long-term follow-ups assessment required to ensure treatment efficacy. Unterhitzenberger et al. (2019) suggested evaluating evidence-based TF-CBT treatments for refugee children within a stepped care design would allow support, not only those diagnosed with trauma symptoms, but also to bring about considerable development in mental health support for traumatized refugee children. However, ethical concerns would make the implementation difficult to achieve, particularly if studying long-term effects (Rubin & Babbie, 2016). What is need is to include independent evaluators in the studies rather than principal investigators that would help reduce any possible selection bias in determining the outcome of the TF-CBT intervention.

Considering the vulnerability of refugee children, as evidenced by their traumatic experiences (Gadeberg et al., 2017), studies should utilize culturally competent personnel with supervised experience to provide TF-CBT in the specific refugee children population group. There is a need to expand TF-CBT components in refugee children’s treatment to include familiar concepts, naming of feelings triggered by cultural diversities, and understanding cultural differences in trauma symptoms treatment. Interpreters should also be required to go through a mandated TF-CBT manual to familiarize themselves with the treatment manual’s language. This will help increase the level of accurate interpretation of trauma-related concepts and avoid miscommunication during the therapeutic sessions. Although personnel delivering TF-CBT are required to have a master’s degree in any mental health related field (TF-CBT National Therapist Certification Program, 2019), these education requirements should be limited to at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent for the interpreters. What is more important is to provide TF-CBT training offered in a culturally sensitive manner to interpreters, and this would allow more diverse interpreters without specific mental health advanced certifications to participate in the studies involving TF-CBT in order to improve their interpretive skills, increase efficiency and acess to personnel with similar cultural values, and partly because interpreters are not providing therapies, but only assisting in ensuring high quality and reliable communication during TF-CBT sessions. With few studies available in TF-CBT, there is a need to include studies written in other languages to increase the scope of literature in the systematic reviews that will be conducted in the future. More so, future studies conducting TF-CBT should aim to increase the age to 21 years and expand the scope of the review to internally displaced children and adolescents, and youth rather than restricting to refugee children alone.

Conclusion

All the four studies in this review, though pilot in nature, indicate that challenges to conducting TF-CBT with traumatized refugee children from different cultural backgrounds can be overcome. More research is needed to determine if tweaks or adaptations could make TF-CBT more effective with refugee children; however, as it stands now, there is sufficient evidence in this review’s findings to assure mental health professionals that refugee children can be treated with TF-CBT to some level of success.

Abbreviations

- A-DES

Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale

- CAPS-CA

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents

- CASP

Critical Appraisal Skills Program

- CATS

Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen

- CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- CCPT

Client Centered Play Therapy

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition

- DIMDCA

The Diagnostic Interview for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence

- KIDNET

Narrative Exposure Therapy for Children

- MFQ

The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire

- PDS

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale

- PHQ-15

The Patient Health Questionnaire Physical Symptoms

- PROPS

Parent Report of Posttraumatic Symptoms

- PTSD

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- PTSS

Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms

- RCT

Randomized Control Trials

- SCARED

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders

- SDQ

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SCD

Single Case Design

- TF-CBT

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- TS

Trauma Symptoms

- UCLA-PTSD

The University of California Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index

- UPS

Uncontrolled Pilot study

Supporting Information

PRISMA Flow Diagram to show the process of Study (XLSX 14 kb)

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest in this systematic review.

Informed Consent

No informed consent needs to be obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alayarain, A. (2017). Children of refugees: Torture, human rights, and psychological consequences. E-Book.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

- Anani, G. (2013). Dimension of gender-based violence against Syrian refugees in Lebonaon. Syria Crisis http://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/detention/detention/anani.pdf.

- Bass, J., Bearup, L., Bolton, P., Murray, L., & Skavenski, S. (2011). Implementing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) among formerly trafficked-sexually abused girls in Cambodia: A feasibility study. John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Bogdanski S, Chang BC. Collecting grey literature: An annotated bibliography, with examples from the sciences and technology. Science & Technology Libraries. 2005;25(3):35–70. doi: 10.1300/J122v25n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnacker I, Goldbeck L. Family-based trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with three siblings of a refugee family. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 2017;66(8):614–628. doi: 10.13109/prkk.2017.66.8.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland, A., Cherry, M.G., & Dickson, R. (2017). Doing a systematic review (2nd edition). SAGE.

- Bridging Refugee Youth and Children’s Services (2020). Retrieved from https://brycs.org

- Campbell and Cochrane Collaboration. (2018). Better evidence for the better world. Retived from campbellcollaboration.org.

- Campbell Collaboration (2019). What is a systematic Review? Retrieved from https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/what-is-a-systematic-review.html

- Carrion VG, Wong SS. Can traumatic stress alter the brain? Understanding the implications of early trauma on brain development and learning. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:S23–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary CE, McMillen JC. The data behind the dissemination: A systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Adverse Childhood Experiences Study: Prevalence of individual adverse childhood experiences. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ace/prevalence.htm

- Cochrane Community (2018). Promising and registering new Cochrane Review. Retrieved from https://community.cochrane.org/review-production/production-resources/proposing-and-registering-new-cochrane-reviews

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for traumatized children and families. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2015;24(3):557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (2008). Trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(4), 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. Guildford Press.

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2017). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. The Guilford Press.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme-CASP (2018). Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Eberle-Sejari R, Nocon A, Rosner R. Zur Wirksamkeit von psychotherapeutischen Interventionen bei jungen Flüchtlingen und Binnenvertriebenen mit posttraumatischen Symptomen – Ein systematischer review (translation of title: Efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions for young refugees and internally displaced persons – A systematic review) Kindh Entwickl. 2015;24:156–169. doi: 10.1026/0942-5403/a000171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehntholt KA, Yule W. (2006). Practitioner review: Assessment and treatment of refugee children and adolescents who have experienced war-related trauma. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1197–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkes CE. Thought field therapy and trauma recovery. International Journal Emergency on Mental Health. 2002;4(22):99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadeberg AK, Montgomery E, Frederiksen HW, Norredam M. Assessing trauma and mental health in refugee children and youth: a systematic review of validated screening and measurement tools. European Journal of Public Health. 2017;27(3):439–446. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerger H, Munder T, Barth J. Specific and nonspecific psychological interventions for PTSD symptoms: A meta-analysis with problem complexity as a moderator. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70:601–615. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian AK, Karayan I, Pynoos RS, Minassian D, Najarian LM, Steinberg AM, Fairbanks LA. Outcome of psychotherapy among early adolescents after trauma. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:536–542. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Prendes A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and social work values: a critical analysis. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics. 2012;9(2):2. [Google Scholar]

- Grand Challenges for Social Work. (2018). University of Maryland, School of Social Work. Retrieved from https://grandchallengesforsocialwork.org/news/.

- Hilado, A., & Lundy, M. (2018). Models for practice with immigrants and refugees: Collaboration, cultural awareness and integrative theory. Sage.

- Jensen TK, Holt T, Ormhaug SM, Egeland K, Granly L, Hoaas LC, Hukkelberg SS, Indregard T, Stormyren SD, Wentzel-Larsen T. A randomized effectiveness study comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with therapy as usual for youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent. 2014;43:356–369. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalt A, Hossain M, Kiss L, Zimmerman C. Asylum seekers, violence and health: A systematic review of research in high-income host countries. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(3):e30–e42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamerman, S. B., & Gatenio-Gabel, S. (2014). Social work and child well-being. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being. Springer. 10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_22.

- Kinzie JD, Cheng K, Tsai J, Riley C. Traumatized refugee children: The case for individualized diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:534–537. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000224946.93376.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang JM, Ford JD, Fitzgerald MM. An algorithm for determining use of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy Theory Research. 2010;47:554–569. doi: 10.1037/a0021184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lely, J., Smid, G. E., Jongedijk, R. A., W Knipscheer, J., & Kleber, R. J. (2019). The effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy: a review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. European journal of psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1550344. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1550344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lustig S, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, Geltman P, Ellis H, Kinzie JD, Saxe GN. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:24–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos LR. Effects of interpreter on evaluation of psychopathology in non-English speaking patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;136(2):171–174. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EA, Butler K, Roche T, Cumming J, Taknint JT. Refugee youth: A review of mental health counselling issues and practices. Canadian Psychology. 2016;57(4):308–319. doi: 10.1037/cap0000068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millard LA, Flach PA. Higgins JP. Machine learning to assist risk-of-bias assessments in systematic reviews. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2016;45(1):266–277. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Cohen JA, Ellis BH, Mannarino A. Cognitive behavioral therapy for symptoms of trauma and traumatic grief in refugee youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinic. 2008;17:585–604. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Skavenski S, Kane JC, Mayeya J, Dorsey S, Cohen JA, et al. Effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy among trauma-affected children in Lusaka, Zambia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;169:761–769. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L.K., Skavenski, S., Kane, J.C., Mayeya, J., Dorsey, S., Cohen, J.A., Michalapoulos, L.T., Imasiku, M., & Bolton, PA. (2015). Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Bheavioral Therapy Among Trauma-Affected Children in Lusaka, Zambia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 169(8):761–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murray, L. K., & Skavenski, S. A. (2012). International settings. In J. A. Cohen, A. P. Mannarino, & E. Deblinger (Eds.), Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: treatment applications (pp. 225–252). Guilford Press.

- National Association of Social Workers. (2005). Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/Events/Celebrations/NASW-50th-Anniversary.

- National Child Stress Network Refugee Task Force [NCTSNRTTF]. (2005). Mental health interventions for refugee children in resettlement. White paper II. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/refugee-trauma

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2012). Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/interventions/trauma-focused-cognitive-behavioral-therapy

- Nocon A, Eberle-Sejari R, Unterhitzenberger J, Rosner R. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in war-traumatized refugee and internally displaced minors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2017;8:1–15. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1388709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palic S, Elklit A. Psychosocial treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult refugees: A systematic review of prospective treatment outcome studies and a critique. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;131(1):8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. R. (2016). Empowerment series: Research methods for social work. Cengage Learning.

- Schottelkorb AA, Doumas DM, Garcia R. Treatment for childhood refugee trauma: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2012;21:57–73. doi: 10.1037/a0027430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, Burns BJ, Kolko DJ, Putnam FW, Amaya-Jackson L. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:156–183. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TF-CBT National Ceritification Program. (2019). TF-CBT Certification Criteria. Retrieved from https://www.tfcbt.org/tf-cbt-certification-criteria/.

- Thomsona C, Vidgen A, Roberts NP. Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2018;63:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauma and Community Resilience Center. (2020). Boston Children’s Hospital. Retrieved from https://www.childrenshospital.org/centers-and-services/programs/o-_-z/trauma-and-community-resilience-center.

- Tyrer RA, Fazel M. School and community-based interventions for refugee and asylum seeking children: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2008). Definition of refugee from immigration and nationality act. Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

- Unterhitzenberger J, Eberle-Sejari R, Rassenhofer M, Sukale T, Rosner R, Goldbeck L. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with unaccompanied refugee minors: A case series. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:260. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0645-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterhitzenberger J, Rosner R. Case report: Manualized trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with an unaccompanied refugee minor girl. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2016;7:29246. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.29246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterhitzenberger J, Wintersol S, Lang M, Konig J, Rosner R. Providing manualized individual trauma-focused CBT to unaccompanied refugee minors with uncertain residence status: A pilot study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2019;13:22. doi: 10.1186/s13034-019-0282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasserman, D. S. (2019). Thinking, moving, and feeling: A proposed movement and behavioral intervention for refugee children with trauma (Order No. 10812711) [Doctoral Dissertation, William James College]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, Currie C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379:1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women’s Refugee Commission. (2020). Creating a Better World for Refugees. Retrieved from https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Mental health promotion and mental health care in refugees and migrants. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2018 (Technical guidance on refugee and migrant health). Retrieved from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/386563/mental-health-eng

- Yasinski C, Hayes AM, Ready CB, Cummings JA, Berman IS, McCauley T, Webb C, Deblinger E. In-session caregiver behavior predicts symptom change in youth receiving trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84(12):1066–1077. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights. (2020). Child Advocate Program. Retrieved from https://www.theyoungcenter.org/child-advocate-program-young-c