Abstract

Background

Acrylic PMMA bone cement is an essential component in cemented implants and formed the cement-bone and cement-implant interfaces. The information on the fracture parameters of PMMA bone cement would be decisive for all doctors, researchers, and orthopaedic surgeons.

Purpose

This review aims to indicate the parameters responsible for the variation in the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. This mini-review also points out some limitations of the earlier published research article, which can be added in the future analysis and can be helpful to get the more realistic data of the fracture parameters of PMMA bone cement.

Conclusion

Different mixing techniques, storage medium, temperature, loading conditions, frequency and environment, cement viscosity, type of specimen, and the ASTM standards (shape, size, and geometry), constituents, loading rate, and cement porosity were the critical parameters to affect the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. This study will also be helpful to increase the structural integrity of PMMA bone cement and the cemented implant.

Keywords: PMMA bone cement, Cemented implants, Fracture toughness, Porosity, Mixing techniques, Storage medium, Viscosity, Fatigue, Mechanical properties

Introduction

Acrylic PMMA bone cement plays a very important role in the success of the cement-bone and cement-implant interface of the cemented implants [1–4]. To enhance the tensile strength, shear strength, and fracture properties of PMMA bone cement, polycaprolactone (PCL) fiber can be used [5]. The viscosity of the PMMA bone cement also plays a critical role and significantly affects the cement penetration [6–8]. Cement penetration is generally considered to influence the interface failure strength [9]; therefore, it has been found that cement with lower viscosity resulted in increased strength of the cement–bone interface [6]. Fracture properties of PMMA bone cement change with the manufacturer (Simplex-P and Zimmer), viscosity (low viscosity and high viscosity), and mixing techniques [10]. More fracture-resistant in bone cement can be obtained by considering centrifuging and slow-hand mixed technique as compared to uncontrolled hand mixing (UHM) technique [10].

Numerous researchers have studied the effect of different mixing techniques of cement, storage temperature, cement porosity, the effect of frequency and environment, cement pressure on tensile strength, different American standard for testing on the different mechanical properties as well as fracture toughness of acrylic bone cement [10–23]. The cemented implants are mainly composed of two interfaces, cement-bone, and implant–cement interface. There is no mechanical bonding between bone, bone cement, and implant; therefore, PMMA bone cement is considered to provide an interlocking effect in the cement-bone and cement-implant interface of cemented implants [9, 24–26]. The success of a cemented implant is directly related to the reliability and longevity of its cement and implant. Macro and microvoids in the PMMA bone cement were also one of the major influencing parameters in the failure analysis of PMMA bone cement, and they promote the interface debonding of the cemented implants [27]. The crack may propagate circumferentially at the interfaces as well as radially to the bone cement. By keeping this fact in mind, several researchers studied the fracture properties and crack propagation behavior of bone cement [10, 23].

To the author’s knowledge, there is a scarcity of data related to various parameters which can affect the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement and consequently the debonding strength of the interfaces of the cemented implant. Considering the safety of cemented implants, it brings the urgency of the study that should specify all the influencing parameters to the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. So, the idea of this mini-review is to provide information about the involvement of several factors in the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. There were several shortcomings to the previously published studies as mentioned in the limitations and future scope section of this mini-review. Solutions to the shortcomings of the earlier published studies could also help us safeguard the joints and enhance the longevity of cemented implants.

Methodology

The articles included in this review article were selected and evaluated based on the effects of several factors on fracture characteristics of PMMA bone cement [1, 3, 4, 7, 12, 14, 17, 19, 22]. Though, some papers were also added to observe the application of cement mantle in cemented implants as well as to determine the fracture properties of cement-bone and cement-implant interface of cemented implants [24–26]. The search strategy considered for the article selection in this review is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A systematic strategy for article selection in this review

Strength of the Available Literature

Authors have rightly pointed out the range of the fracture toughness of the PMMA bone cement (Table 1). Several studies included the effect of different parameters on fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. However, the effects of many factors are also needed to be evaluated.

Table 1.

Fracture toughness of acrylic PMMA bone cement in terms of stress intensity factors (SIFs) (MPa.m1/2)

| Sl. no. | Study and year | Stress intensity factors (SIF) (MPa m1/2) | Parameter studied | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nguyen et al. (1997) | 0.6–2.0 | Fatigue loading | [1] |

| 2 | Khaled et al. (2011) | 0.8–1.0 | Nano-sized titania fibers | [3] |

| 3 | Ziegler and Jaeger (2020) | 0.94–1.99 | Different manufacturer, viscosity, and mixing techniques | [4] |

| 4 | Graham et al. (2000) | 1.2–2.3 | Mixing method, sterilization treatment, and molecular weight | [7] |

| 5 | Wang and Pilliar (1982) | 0.7–1.8 | Different manufacturer, viscosity, and mixing techniques | [12] |

| 6 | Lewis (1999) | 1.51–2.7 | Different test specimen configuration, and sterilization method | [14] |

| 7 | Lewis (1997) | 1.1–2.32 | Different cement manufacturers, mixing techniques, loading conditions, and type of test specimen | [17] |

| 8 | Vila et al. (1998) | 1.20–2.40 | Different mixing techniques, storage medium, porosity, and constituents | [19] |

| 9 | Guandalini et al. (2004) | 1.55–1.90 | Different testing standards (ASTM E399 and ASTM D5045) | [22] |

| 10 | Lewis (1994) | 1.00–2.00 | Different cement and test specimen configuration | [34] |

Weakness of the Available Literature

The effect of different modes of loading, different angles of loading, effects of temperature are still not clear in the available literature. Another fracture parameter, the strain energy release rate of PMMA bone cement is needed to be evaluated for a complete understanding of the fracture properties. Considering the application of bone cement, there is a dearth of data related to the effect of cement penetration (due to the micro and macro grooves) on the interfacial fracture mechanism of cemented implants.

Results

Doctors, surgeons, and researchers have performed several studies on the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement to predict the life expectancy of PMMA bone cement and ultimately to enhance the structural integrity of cemented implants. Various factors may lead to fracture in the cement mantle around a cemented implant as specified by the researchers [24–26, 28, 29]. These are as follows:

Improper positioning of the implant

Poor cementing techniques

Poor quality of implant material

Interfacial crack

Age and bone remodeling

Obesity and loading mechanisms.

Improper positioning of the implant can lead to the non-uniform cement mantle thickness in cemented implants [25, 29]. Therefore, chances of stress concentration on the location near less cement mantle thickness increases subsequently would enhance the failure of the cemented implant [25, 29]. Poor cementing techniques may lead to the microvoids and porosity between cement-bone and cement-implant interface in cemented implants [7, 22, 23]. Voids and porosity reduce the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement as well might lead to the interface failure of cemented implants [7, 22, 23]. Poor quality of implant materials might not be able to transfer load from implants to bone also causes more stresses in the cement mantle of cemented implants [24, 28]. There is also a possibility that microcrack presented in the PMMA bone cement and interfaces of the cemented implant may propagate and causes damage in PMMA bone cement and consequently initiates the loosening of the cemented implant [24–26]. Bone density keeps changing with aging. Stiffness and bone density reduces as the age increases [30, 31], which generates more load in the cement mantle of the cemented implant. Therefore, this might be one reason that the loosening of cemented prostheses increases as the age of the patient increases. Obesity and fatigue loading conditions at the time of running, climbing, sports activities, and in accidental cases may also lead to the fracture in the cement mantle and ultimately causes the failure of cemented prosthesis [30–32].

PMMA bone cement plays a crucial role in the success of cemented implants; therefore, the inclusion of different mixing methods, fatigue and fracture properties, and the effect of storage temperature of acrylic bone cement in some experimental analysis would also be very helpful in the interfacial fracture mechanics of cemented implants [14, 17]. All types of bone cement used in cemented implants were commercially available acrylic bone cement (high or low viscosity) with the following ingredients: (a) a liquid monomer that included Methyl Methacrylate, N-Dimethyl para-toluidine, and Hydroquinone, and (b) a powder containing Methyl Methacrylate–styrene copolymer, Poly-methyl methacrylate, and Barium Sulphate (Fig. 2). Bone cement also consists of initiator, radio-opacifier, and antibiotics in powder form and accelerator, and stabilizer in liquid monomer [33]. Cement-bone and cement-implant interfaces of cemented implants can be prepared under consistent conditions to ensure dimensional accuracy and density (according to manufacture guidelines).

Fig. 2.

a High and b low viscosity of PMMA bone cement (powder and liquid monomer)

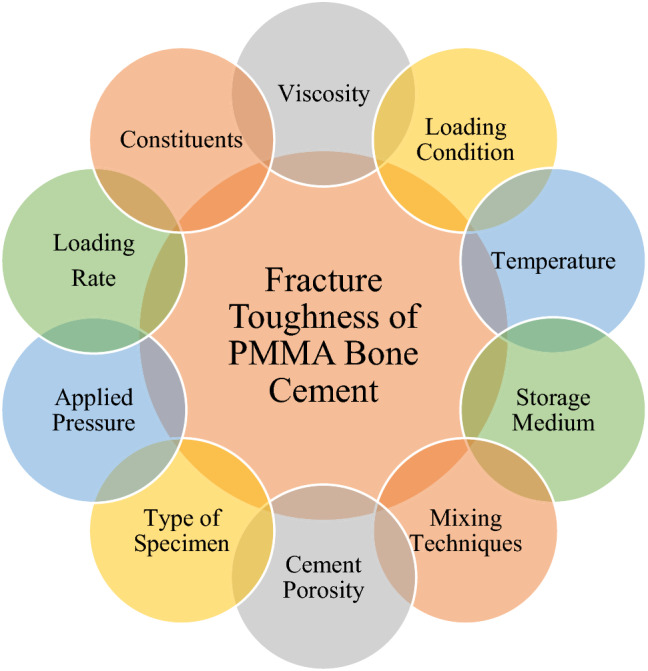

One of the foremost disadvantages of bone cement in joint replacement is the crack generation and propagation in cement as well as generation of the wear debris, resulting in prosthetic loosening and periprosthetic osteolysis [33]. The formation of wear debris from roughened metallic surfaces of the implant and the bone cement can cause local inflammatory activity, consequential in chronic complications to hip replacements [33]. The fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement influences the load-carrying capacity of cement mantle and longevity of cemented implant (hip arthroplasty, knee arthroplasty, etc.). The present mini-review provides an overview of the several factors, which primarily affect the fracture properties of PMMA bone cement (Fig. 3) and consequently affects the failure strength of cement mantle, cement-bone, and cement-implant interfaces of cemented implants.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the influencing parameters on fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement

Discussion

The physiological environment (storage medium) has a weighty effect upon cyclic loading, fatigue crack growth, and fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. Precisely, the PMMA bone cement is more resistant to both fatigue loading and fatigue fracture toughness in Ringer’s solution (a simulated physiological environment) than in 45% relative humidity [1]. The fatigue fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement was found to be 0.3–0.5 MPa m1/2 in air and 0.6–0.8 MPa m1/2 in Ringer’s solution [1]. One set of PMMA bone cement indicated the increase of the fracture toughness with increasing crack length (including CMW1 + G and several Palacos bone cement); however, another group (with Simplex, SmartSet, Copal, and some Palacos bone cement) did not show an R-curve behavior [4]. The viscosity of PMMA bone cement, mixing techniques, and manufacturer were found to have a great impact on the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. Simplex bone cement was found to have approximately 50% less fracture toughness than palacos, smartset, and copal [4]. However, one experimental study shows that Simplex-P has superior fracture toughness to Zimmer LVC cement after storage in water for two months at 37 °C [12].

The vacuum mixing technique was found to be superior to hand mixing and produces less porosity [7]. Fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement was found to have around 20% more for vacuum mixing than hand mixing [7]. Similarly, one of the researchers stated that vacuum mixed PMMA bone cement has 120% more fatigue life and less viscosity than hand-mixed PMMA bone cement [23]. Though, one study reported the marginal change in the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement samples considering hand and vacuum mixing techniques [19]. Type of the specimen preparation (shape and size of the specimen) also affects the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement [14]. The fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement using chevron-notched short red (CNSR) specimen was found to be approximately 15% higher than the single-edge notched bending (SENB) [14]. The fracture toughness obtained through SENB and compact rectangular tension (RCT) specimens were almost invariable by considering linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) [14]. A review article published 25 years ago rightly points out that the fracture toughness and other material properties (tensile, shear, compressive, bending) of PMMA bone cement differs with different mixing methods, constituents, and manufacturers [17].

Different American standards (ASTM E399 and ASTM D5045) of testing also influence the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement [22]. ASTM E399 procedure was found to have 13% lower fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement than that calculated following the ASTM D5045 procedure [22]. The availability of microporosity (voids) on the fracture surface of the specimen also affected the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement [22]. Similarly, the storage temperature of cement constituents was found to affect the porosity and fatigue life of PMMA bone cement [23]. Porosity decreases and the fatigue life of PMMA bone cement increases as the storage temperature decreases from 21 to 4 °C [23]. However, one study indicated that some additives and constituents might not produce a significant difference in the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement [29]. The addition of nano-sized titania fibers in PMMA bone cement was found to be effective in increasing the fracture toughness, flexural strength (FS), and flexural modulus (FM) by 22.5, 6.77, and 11.06%, respectively [3]. One of the researchers added acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) to a conventional acrylic PMMA bone cement matrix [19]. The fracture toughness increased up to 60% when the amount of ABS reached 20% of volume fraction to the PMMA bone cement [19]. Fracture toughness of vacuum mixed PMMA bone cement was found to be marginally increased when the samples were stored in the saline solution as compared to dry samples of PMMA bone cement [19].

Researchers have found several parameters which affect the fracture parameters of PMMA bone cement, i.e., the viscosity of bone cement, loading condition, different geometric ASTM standards (type of specimen, shape, and size of the specimen), temperature, constituents, applied pressure, storage medium, mixing techniques, loading rate, and cement porosity as shown in Fig. 3 [2, 4, 7, 12, 14, 22, 34]. Fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement was found to vary within the range of 0.6–2.7 MPa m1/2 [2, 4, 7, 12, 14, 22, 34] (Table 1). The variation in the fracture toughness values may be due to the several assumptions and limitations considered in the previous studies, as indicated below. The assumptions and limitations of previously available literature provide motivation and research objectives for further studies of the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement in the future.

Limitations and Future Scope

This mini-review found several limitations of the earlier literature, which can be included in future studies to get more realistic data on fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement. Limitations are given below.

-

I.

Maximum analysis to determine the fracture toughness of bone cement was performed considering straight and linear crack [2, 4, 7, 12, 14, 22, 29]; however, in real-life problems, the crack can be curvy, inclined, and non-linear. Therefore, the experimental and numerical analysis of bone cement with curvature crack will be very helpful and realistic.

-

II.

Maximum of the earlier published studies were performed considering mode-I loading to determine the fracture toughness of bone cement; however, in real-life problems, bone cement experiences mode-II, mixed-mode (mode-I + mode-II), and mode-III loading as well. Therefore, the inclusion of these loading conditions will also help to solve the more realistic problem.

-

III.

Mixing techniques, pressurization techniques, and cement porosity have a huge influence on the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement; however, very few studies were available to determine their combined effect on the mechanical and fracture properties of PMMA bone cement. Therefore, the inclusion of these parameters in the fracture analysis of PMMA bone cement will be very helpful to determine the failure analysis cement-bone and cement-implant interface of cemented implants.

-

IV.

Most of the researchers explain the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement in terms of stress intensity factors (SIF); however, energy release rate could also be one of the important parameters to define the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement.

-

V.

The effect of cement penetration as well as the shape, size, and the number of grooves on the bone preparation on the interfacial strength of cemented implants under different loading conditions would also need to be evaluated.

Conclusion

This mini-review concluded that the PMMA bone cement plays a key role in the longevity of the cemented implant and the fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement is dependent on so many parameters. The limitations pointed out in this mini-review would also be helpful for future analysis to get the more realistic fracture toughness data of PMMA bone cement. Additionally, this knowledge of fracture toughness of PMMA bone cement will provide the basis for more accurate life predictions, enhance the structural integrity and life expectancy (longevity) of the cemented implant.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge IIT Mandi for this study.

Author Contributions

AK: conceptualization, visualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, software, writing-original draft. Dr. RG: conceptualization, visualization, resources, guidance, supervision, writing-review and editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standard Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ajay Kumar, Email: ajaym9882@gmail.com.

Rajesh Ghosh, Email: rajesh@iitmandi.ac.in.

References

- 1.Nguyen NC, Maloney WJ, Dauskardt RH. Reliability of PMMA bone cement fixation: Fracture and fatigue crack-growth behaviour. Journal of Materials Science. Materials in Medicine. 1997;8:473–483. doi: 10.1023/A:1018574109544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saleh KJ, El Othmani MM, Tzeng TH, Mihalko WM, Chambers MC, Grupp TM. Acrylic bone cement in total joint arthroplasty: A review. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2016;34:737–744. doi: 10.1002/jor.23184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khaled SMZ, Charpentier PA, Rizkalla AS. Physical and mechanical properties of PMMA bone cement reinforced with nano-sized titania fibers. Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 2011;25:515–537. doi: 10.1177/0885328209356944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziegler T, Jaeger R. Fracture toughness and crack resistance curves of acrylic bone cements. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2020;108:1961–1971. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandaker M, Utsaha KC, Morris T. Fracture toughness of titanium-cement interfaces: Effects of fibers and loading angles. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2014;9(1):1689–1697. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S59253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham J, Ries M, Pruitt L. Effect of bone porosity on the mechanical integrity of the bone–cement interface. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series A. 2003;85(10):1901–1908. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham J, Pruitt L, Ries M, Gundiah N. Fracture and fatigue properties of acrylic bone cement: The effects of mixing method, sterilization treatment, and molecular weight. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):1028–1035. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.8188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone JJS, Rand JA, Chiu EK, Grabowski JJ, An KN. Cement viscosity affects the bone–cement interface in total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1996;14(5):834–837. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann KA, Ayers DC, Werner FW, Nicoletta RJ, Fortino MD. Tensile strength of the cement–bone interface depends on the amount of bone interdigitated with PMMA cement. Journal of Biomechanics. 1997;30(4):339–346. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(96)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause WR, Miller J, Ng P. The viscosity of acrylic bone cements. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1982;16(3):219–243. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820160305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause WR, Krug W, Miller J. Strength of the cement–bone interface. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1982;163:290–299. doi: 10.1097/00003086-198203000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perek J, Pilliar RM. Fracture toughness of composite acrylic bone cements. Journal of Materials Science. Materials in Medicine. 1992;3:333–344. doi: 10.1007/bf00705365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper EJ, Bonfield W. Tensile characteristics of ten commercial acrylic bone cements. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;53(5):605–616. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200009)53:5<605::AID-JBM22>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis G. Apparent fracture toughness of acrylic bone cement: Effect of test specimen configuration and sterilization method. Biomaterials. 1999;20(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhambri SK, Gilbertson LN. Micromechanisms of fatigue crack initiation and propagation in bone cements. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1995;29(2):233–237. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JA, Provan JW, Krygier JJ, Chan KH, Miller J. Fatigue of acrylic bone cement–effect of frequency and environment. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1989;23(8):819–831. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820230802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis G. Properties of acrylic bone cement: State of the art review. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1997;38(2):155–182. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199722)38:2<155::AID-JBM10>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saha S, Pal S. Mechanical properties of bone cement: A review. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1984;18(4):435–462. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820180411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vila MM, Ginebra MP, Gil FJ, Planell JA. Effect of porosity and environment on the mechanical behavior of acrylic bone cement modified with acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene particles: I. Fracture toughness. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1999;48(2):121–127. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(1999)48:2<121::aid-jbm5>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson JM, Eveleigh R, Hamer AJ, Milne A, Miles AW, Stockley I. Effect of mixing technique on the properties of acrylic bone-cement: A comparison of syringe and bowl mixing systems. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2000;15(5):663–667. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.6620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Askew MJ, Steege JW, Lewis JL, Ranieri JR, Wixson RL. Effect of cement pressure and bone strength on polymethylmethacrylate fixation. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1983;1(4):412–420. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100010410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guandalini L, Baleani M, Viceconti M. A procedure and criterion for bone cement fracture toughness tests. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine. 2004;218(6):445–450. doi: 10.1243/0954411042632144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis G. Effect of mixing method and storage temperature of cement constituents on the fatigue and porosity of acrylic bone cement. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1999;48(2):143–149. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(1999)48:2<143::AID-JBM8>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A, Ghosh R, Kumar R. Effects of interfacial crack and implant material on mixed-mode stress intensity factor and prediction of interface failure of cemented acetabular cup. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part B Applied Biomaterials. 2020;108(5):1844–1856. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A, Sanjay D, Mondal S, Ghosh R, Kumar R. Influence of interface crack and non-uniform cement thickness on mixed-mode stress intensity factor and prediction of interface failure of cemented acetabular cup. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics. 2020;107(February):102524. doi: 10.1016/j.tafmec.2020.102524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Ghosh R, Kumar R. Effect of interfacial crack on the prediction of bone–cement interface failure of cemented acetabular component. In: Saha SK, Mukherjee M, editors. Recent advances in computational mechanics and simulations. Singapore: Springer; 2021. pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann KA, Gupta S, Race A, Miller MA, Cleary RJ, Ayers DC. Cement microcracks in thin-mantle regions after in vitro fatigue loading. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2004;19:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar A, Ghosh R, Kumar R. Effect of implant materials on bone remodelling around cemented acetabular cup. In: Kumar R, Chauhan VS, Talha M, Pathak H, editors. Machines, mechanism and robotics. Singapore: Springer; 2022. pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanjay D, Mondal S, Bhutani R, Ghosh R. The effect of cement mantle thickness on strain energy density distribution and prediction of bone density changes around cemented acetabular component. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine. 2018;232:912–921. doi: 10.1177/0954411918793448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Changulani M, Kalairajah Y, Peel T, Field RE. The relationship between obesity and the age at which hip and knee replacement is undertaken. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 2008;90-B:360–363. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.90b3.19782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del-Valle-Mojica JF, Alonso-Rasgado T, Jimenez-Cruz D, Bailey CG, Board TN. Effect of femoral head size, subject weight, and activity level on acetabular cement mantle stress following total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2019;37:1771–1783. doi: 10.1002/jor.24310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zant NP, Heaton-Adegbile P, Hussell JG, Tong J. In vitro fatigue failure of cemented acetabular replacements: A hip simulator study. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2008;130:1–9. doi: 10.1115/1.2904466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaishya R, Chauhan M, Vaish A. Bone cement. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2013;4:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis G. Effect of methylene blue on the fracture toughness of acrylic bone cement. Biomaterials. 1994;15:1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.