Abstract

Interprofessional collaboration has become an essential component in the treatment of individuals with autism spectrum disorder, as practitioners from a range of disciplines are often necessary to address the core features and co-occurring conditions. Theoretically, such cross-disciplinary collaboration results in superior client care and maximal outcomes by capitalizing on the unique expertise of each collaborating team member. However, conflict in collaborative practice is not uncommon given that the treatment providers come from varying educational backgrounds and may have opposing core values, fundamental goals, and overall approaches. Although the overarching interest of each of these professionals is to improve client outcomes and quality of life, they may be unequipped to effectively navigate the barriers to collaboration. This article reviews the potential benefits and misconceptions surrounding interprofessional collaboration and highlights common sources of conflict. As a proposed solution to many of the identified issues, we offer a set of standards for effective collaborative practice in the interprofessional treatment of autism spectrum disorder. These standards prioritize client care and value each discipline’s education and unique contributions. They are intended to function as core standards for all treatment team members, promote unity, prevent conflict, and ultimately help practitioners achieve the most integrated collaborative practice among professionals of varying disciplines.

Keywords: interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary, collaboration, autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) continues to be one of the most prevalent childhood disorders, characterized by deficits in communication and impairments in social interactions, as well as restricted or repetitive patterns of thoughts and behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Zablotsky et al., 2015). ASD is often coupled with comorbid gastrointestinal complications, sleep disturbances, seizure disorders, and mental health issues, among others (Dillenburger, 2011; LaFrance et al., 2019; Strunk et al., 2017). The complex symptomatology and high comorbidity associated with ASD frequently involve treatment delivery across a range of professional disciplines (e.g., Cox, 2019; Kelly & Tincani, 2013; LaFrance et al., 2019; Strunk et al., 2017). Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) are commonly part of a larger, interprofessional treatment team that also includes speech-language pathologists (SLPs), occupational therapists, special educators, clinical psychologists, and medical doctors, among others (Cox, 2012; LaFrance et al., 2019). These professionals may find opportunities to work collaboratively to improve health and educational outcomes for individuals with ASD (Brodhead, 2015; LaFrance et al., 2019; Strunk et al., 2017), yet, oftentimes, difficulties and problems arise in the collaborative process and impede the treatment team’s ability to completely unite in providing the most efficient and effective interprofessional care. Thus, the purpose of this article is to provide information on collaboration, outline the barriers to providing optimal collaborative care, and propose a set of standards to promote the transdisciplinary collaboration of professionals in the treatment of individuals with ASD.

Interprofessional Collaboration

Spectrum of Collaboration

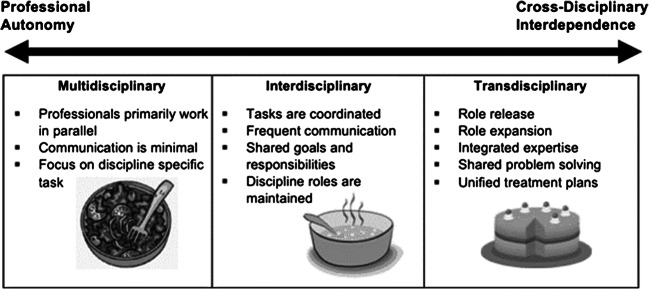

Literature on interprofessional collaboration indicates that there are varying extents to which professionals from different disciplines collaborate when working together as part of a treatment team (e.g., D’Amour et al., 2005 ; Thylefors et al., 2005). For example, in some collaborative relationships, professionals may not interact with one another on a regular basis, whereas in others, professionals may meet regularly and develop treatment plans cohesively (D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005). D’Amour et al. (2005) described this spectrum of collaboration as a continuum of professional autonomy varying in degrees of interdependence (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Spectrum of Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration. Note. The figure depicts a continuum of collaborative practice ranging from professional autonomy to cross-disciplinary interdependence with characteristics describing multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary collaboration. Images of a salad for multidisciplinary, soup for interdisciplinary, and cake for transdisciplinary represent analogies described by Choi and Pak (2006)

Various terms, such as “multidisciplinary,” “interdisciplinary,” and “transdisciplinary,” are frequently used to refer to interprofessional collaborative practices (D’Amour et al., 2005). Although these terms may be mistakenly used synonymously, each term indicates a different degree of collaboration among treatment team professionals (Bernstein, 2015; Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006; D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005; see Fig. 1). We recommend that the term “interprofessional” be used as an umbrella term referring to all models of collaboration whereby two or more professionals representing different disciplines work together in treatment or assessment of a shared client. Terms such as “multidisciplinary,” “interdisciplinary,” and “transdisciplinary” refer to specific models of collaboration and are described further to clarify the distinction.

Multidisciplinary treatment is frequently recommended for the management of ASD; however, the extent of collaboration and integration of expertise is not typically specified (see Cox, 2012; Dillenburger et al., 2014; LaFrance et al., 2019; Strunk et al., 2017). According to Gehlert et al. (2010), the diverse perspectives available through multidisciplinary models may offer a more comprehensive analysis than what might otherwise be achieved via a monodisciplinary (i.e., only one professional from one field) endeavor. In a multidisciplinary model, practitioners operate within the confines of their professional boundaries, each delivering treatment according to their discipline-specific view and often to address a specific and separate deficit (Choi & Pak, 2006; Gehlert et al., 2010). Therefore, professionals work in parallel with an emphasis on the solitary development of goals and interventions (Choi & Pak, 2006), rather than the collaborative process (Collin, 2009; D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005).

Multidisciplinary teams are analogous to salads, wherein various ingredients are included albeit distinct and separate (Choi & Pak, 2006; see Figure 1). Contributions are additive rather than integrative (Bernstein, 2015; Choi & Pak, 2006). For example, information may be exchanged between team members to coordinate care or report progress, but frequent and ongoing communication is not essential (Strunk et al., 2017; Thylefors et al., 2005) because input from other team members does not alter an individual professional’s treatment plan (Choi & Pak, 2006; D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005). Treatment gains may eventually be hindered as a result of this level of professional autonomy and dissociation (Choi & Pak, 2006). Whereas the multidisciplinary model offers more perspectives than a monodisciplinary approach, the narrow, discipline-oriented viewpoint inhibits a broader understanding of the complex variables influencing the client (Gehlert et al., 2010).

Interdisciplinary teams attempt to provide a more comprehensive and integrative approach to client care by combining and coordinating the expertise of the participating professionals (Collin, 2009; Cox, 2012; D’Amour et al., 2005). Interdisciplinary teams are analogous to soups or stews, wherein ingredients cook together to produce unique flavoring but remain distinguishable (Choi & Pak, 2006; see Fig. 1). The distinct roles of each discipline are preserved while the goals and responsibilities are shared (Choi & Pak, 2006; D’Amour et al., 2005; Gehlert et al., 2010; Thylefors et al., 2005). For example, team members may conduct separate and independent evaluations and then work cooperatively to establish goals (Choi & Pak, 2006). This joint approach requires more frequent interactions. As a result, team members often expand their clinical perspectives beyond the boundaries established by their discipline (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006). Although interdisciplinary care trumps a multidisciplinary approach, complete collaboration is not achieved because professionals work independently to target goals that were developed collaboratively. Thus, interdisciplinary care may offer numerous advantages, yet may prevent a fully holistic perspective of multifaceted disorders such as ASD (Gehlert et al., 2010).

Transdisciplinary collaboration synthesizes the discipline-specific expertise of each team member by obscuring the boundaries that typically divide fields (Bernstein, 2015; Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006; Collin, 2009; D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005). Team members expand their individual roles to include duties beyond those traditionally assumed within their scope of practice (i.e., role expansion), as well as impart their individual, specialized knowledge to other team members and accept shared responsibility (i.e., role release; Choi & Pak, 2006). Knowledge and information are deliberately shared through frequent communication using a common, jargon-free vocabulary to promote clarity and unity (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006; Collin, 2009; D’Amour et al., 2005; Gehlert et al., 2010). Worldviews specific to the individual disciplines are assimilated into a synergetic framework (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006; Collin, 2009; Gehlert et al., 2010), allowing the treatment team to share an integrated perspective and generate innovative, yet pragmatic solutions to socially significant issues (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006).

The level of harmony purported by transdisciplinary collaboration demands mutual trust, respect, and confidence among team members (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006; D’Amour et al., 2005) as they are pushed “outside of their comfort zones” (Gehlert et al., 2010, p. 413), away from their autonomous, monodisciplinary views and into a perspective that transcends conventional boundaries (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006). Similar to the interdisciplinary approach previously mentioned, treatment goals are conjointly developed; however, in transdisciplinary collaboration, the clinical skills and interventions are also shared (Boger et al., 2017; Choi & Pak, 2006). Transdisciplinarity has the makings of a hybrid discipline, capitalizing on the unique knowledge and skills of each individual specialist, and combining them into a coherent whole (Collin, 2009). That is, the resulting product is different from and greater than the sum of its individual parts. Transdisciplinary collaboration is analogous to a cake, wherein the ingredients are no longer distinguishable from one another and produce an entirely different product that could not otherwise be created (Choi & Pak, 2006; see Fig. 1). Role release and expansion blur the boundaries that traditionally divide each discipline. The result is a broad, holistic, and shared perspective necessary to develop comprehensive interventions that address multifarious, intertwined variables (Boger et al., 2017; Gehlert et al., 2010) not otherwise achieved in multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary collaboration. Thus, given the high comorbidity and complex symptomatology of ASD, a transdisciplinary approach to collaboration offers the most effective means of assessment and treatment.

Benefits of Collaboration

The potential benefits of interprofessional collaboration are vast and well documented. Although lacking empirical support, many authors have suggested that the interprofessional team unites the strengths and competencies of individual specialists to maximize client outcomes (Brodhead, 2015; Dillenburger et al., 2014; Garman et al., 2006). Lawson (2004) reported that truly effective collaboration may additionally lead to enhanced problem solving, increased efficiency, and access to additional resources. Additionally, Kelly and Tincani (2013) noted that collaboration may be more preferred by clients, increase treatment integrity, and result in better maintenance of acquired skills. Furthermore, Brodhead (2015) highlighted several professional benefits of effective collaborative interactions, including the opportunity to disseminate one’s own science and discipline, understand other disciplines and perspectives, and develop trusting partnerships that may enhance the quality of therapeutic services. Similarly, Hall (2005) suggested that interprofessional collaboration also yields potential benefits for health care organizations, including higher quality client care at reduced costs and greater job satisfaction.

With the literature touting the benefits of interprofessional collaboration, it seems an obvious and rational approach (Dillenburger et al., 2014). Moreover, interprofessional treatment for the management of ASD is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the United Nations Convention for the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Dillenburger et al., 2014; Strunk et al., 2017). Therefore, it is not surprising that interprofessional collaboration is growing in popularity and is considered best practice in the management of ASD (Dillenburger et al., 2014; Lawson, 2004; Strunk et al., 2017). However, Cox (2019) explained that true benefit is only achieved when the collaborative efforts produce greater outcomes than what would otherwise be achieved by services delivered in isolation. Unfortunately, collaboration in clinical practice and research is poorly understood, and the lack of an intervention-oriented concept of collaboration poses a significant problem (Lawson, 2004). Failing to effectively collaborate may result in an incompatible mix of treatments that may produce adverse or even harmful outcomes for clients (Cox, 2019).

Misconceptions

According to Dillenburger et al. (2014), when the concept of collaboration is misconstrued and poorly used, the team “regresses into mere eclecticism”—that is, a “haphazard pick and mix” or a “hodgepodge” of “discipline-specific interventions” (pp. 4–5). Moreover, Schreck and Mazur (2008) described a “buffet approach” to the treatment of ASD, wherein clients have access to a variety of treatment options (e.g., sensory integration, pivotal response training, facilitated communication, secretin treatments, functional communication training, gluten-free diet) and select “a little of this or a little of that” (p. 201).

The available empirical evidence indicates that such eclectic treatment packages result in limited treatment gains (see Eikeseth et al., 2002; Howard et al., 2005; and Howard et al., 2014, for more details). Although some component interventions may be evidence based, the eclectic mix alone is not supported by scientific research (Dillenburger, 2011; McMahon & Cullinan, 2016). Despite these findings, eclecticism continues to be sought out by consumers and sanctioned by practitioners (Howard et al., 2005; McMahon & Cullinan, 2016). Its favor seems to rest on the idea that an eclectic package provides access to a wider array of interventions and the unique benefits each has to offer (Dillenburger, 2011). However, eclecticism shares characteristics of pseudoscience whereby treatments are erroneously deemed scientific, give false hope, and therefore maintain their popularity (Dillenburger, 2011).

We believe that the term “multidisciplinary,” which, by definition, describes autonomous professionals providing care with little to no collaboration, may glamorize and disguise eclecticism. As such, multidisciplinary practice without effective collaboration may be a dangerous approach to the treatment of ASD by fostering more independently delivered eclectic treatments. The resulting mix of eclectic interventions, which are ineffective and consume more time and financial resources, may lead to conflict among team members (Dillenburger et al., 2014; Howard et al., 2005).

Education in Collaboration

Although more integrated care is regarded as an important component of practice in applied behavior analysis (ABA), the degree to which behavioral professionals are trained in collaboration is limited (Kelly & Tincani, 2013). Kelly and Tincani (2013) surveyed over 300 behavioral professionals, 95% of whom reported working with individuals with ASD, and found that 67% had not taken any collaboration courses at the university level, and 45% had not participated in professional development activities that addressed collaborative practice.

Without education or training in collaborative practice, interprofessional collaboration may present challenges. The occupational differences across team members may hinder collaboration and result in discipline silos where professionals operate independently and autonomously (Hall, 2005; Strunk et al., 2017). According to Hall (2005), these discipline silos commence early in the development of the professional. Typically, at the university, multiple areas of specialization operate in isolation, and the aspiring professional is engrossed in the knowledge and culture of their respective discipline and distinguished by a unique identity and value system. Interprofessional collaboration is rarely observed in academia, and interactions among students of differing professions are not necessarily encouraged or facilitated. The culmination of these social and educational experiences establishes a distinct professional worldview (see Garman et al., 2006).

Once the student has completed the requisite education and training, demonstrated the necessary knowledge and skills, and adopted the values specific to the discipline, they may assume the long-awaited occupational identity (Hall, 2005). New professionals embrace and uphold their identity and continue to align with the profession. Loseke and Cahill (1986) described how this discipline persona is significant to the professional and their practice. They read the professional journals associated with their chosen field, attend professional conferences in this same field, and become members of professional organizations in their discipline. Although all of this is important to their continued professional development and to solidifying their identities as practicing professionals, it also limits their exposure to the contributions and advances in other disciplines. It continues the silo approach that defines the higher education experience and makes the professional development journey an extension of this discipline-specific perspective. Thus, in interprofessional collaboration, team members often exude a distinct professional image epitomized by their discipline-specific worldview; this both defines and preserves the scope of their professional authority and, combined with the lack of collaborative education, may catalyze the division and conflict that are common to interprofessional teams (D’Amour et al., 2005; Suter et al., 2009).

Conflict

Throughout their education and training, collaborating professionals have been taught to function as autonomous and separate professionals, bearing their own language and practices (Coben et al., 1997). The vocabulary of the professional is used to represent their knowledge, expertise, and value (Lawson, 2004); however, it can brandish the worldview and validate the occupational image. Thus, mastery of the language of the discipline affords entry into the guild and is often a source of pride. It can be difficult to then move back to a lay translation, and it may be associated with the fear of seeming weaker or less skilled within the profession. Jargon may be used to ensure precision and to convey expertise. In the discipline silo, it is expected and encouraged, but in interprofessional collaboration, it often becomes a barrier (Hall, 2005; Suter et al., 2009). The use of discipline-specific jargon highlights differences across disciplines, makes communication challenging, and might make some professionals feel marginalized in treatment conversations. LaFrance et al. (2019) cautioned behavior analysts specifically against the use of terminology that may hinder collaborative interactions, yet such challenges exist for all members of the interprofessional team.

Furthermore, treatment team professionals may have opposing core values, fundamental goals, and approaches, especially in the selection of treatments and in the evaluation of success (Cascio et al., 2016). Therefore, conflict seems likely inevitable in interprofessional collaboration, and the coveted harmony of integrated care is not so easily achieved (Brown et al., 2011; LaFrance et al., 2019). When conflict arises, it hinders cohesive collaborative practices by impeding the treatment team’s ability to provide efficient, quality treatment and thwarts effective client care (Brown et al., 2011; LaFrance et al., 2019).

Role Boundary Issues

Effective collaboration requires that professionals involved in the coordinated treatment of an individual with ASD understand, recognize, and appreciate the contributions made by other collaborating professionals (LaFrance et al., 2019). However, the unique roles of collaborators within the treatment team are rarely addressed, and disconnect between participating professionals is frequently observed (Brown et al., 2011; Kvarnström, 2008).

Strong identities and professional cultures can create role boundary conflicts, which form additional barriers to collaboration (Kvarnström, 2008; Suter et al., 2009). Role boundary issues refer to a poor understanding of each team member’s role and the value of unique contributions (Brown et al., 2011; Hall, 2005; Kvarnström, 2008 ; Strunk et al., 2017). When the unique knowledge base of each profession is not fully understood, individual members may be deprived of the opportunity to contribute their expertise, or the contributions they make may be devalued or even neglected (Hall, 2005; Kvarnström, 2008). Individual team members may have overlapping practice purviews, or share specific areas of expertise, which complicates role boundaries, makes it difficult to understand the responsibilities of each professional, and is therefore one of the most common sources of interprofessional conflict (Brown et al., 2011; Kvarnström, 2008; Strunk et al., 2017).

These overlapping practice areas may result in role blurring, wherein professional boundaries are less distinct (Hall, 2005; Sims et al., 2015; Suter et al., 2009). Some authors have noted that ambiguity in professional roles may pose a high risk for conflict and further division among interprofessional teams, as it may cause workload imbalances, confusion surrounding individual responsibilities, and professional burnout (Folkman et al., 2019; Hall, 2005; Suter et al., 2009). Contrarily, other authors have identified role blurring as a beneficial and important characteristic of interprofessional collaboration, as it dissolves discipline boundaries, expands professional knowledge and expertise, allows team members to adapt to changing circumstances and needs, and enhances overall client care (Bennett et al., 2016; Sims et al., 2015). Role blurring is a necessary component of transdisciplinary collaboration (D’Amour et al., 2005). The transdisciplinary team intentionally dissolves professional boundaries, and its members reciprocate exchanges of knowledge and competency to achieve fully integrated care for enhanced client outcomes (D’Amour et al., 2005; Kvarnström, 2008; LaFrance et al., 2019).

Communication Failures

Problems related to role boundaries may be further complicated by issues in communication, particularly when team members fail to convey their position or expertise and delegate responsibilities accordingly (Suter et al., 2009). For example, Koenig and Gerenser (2006) described the confusion that families experience when professionals from their child’s treatment team (e.g., SLP, BCBA) provide conflicting recommendations. This can lead to the belief that professionals are not in agreement on practices for best treatment, and may result in distrust from those receiving interprofessional care. As worldviews clash and other disagreements arise, team members must exercise skillful communication practices to quickly and effectively resolve dissonance and present a cohesive and unified team to clients and their families (Brown et al., 2011; Cox, 2019; Suter et al., 2009).

Communication among interprofessional team members is necessary to share knowledge, exchange ideas, and coordinate effective care for clients. Failure to do so often results in professionals retreating to their discipline silos (Hall, 2005; Strunk et al., 2017; Suter et al., 2009). Discipline-specific treatments are not delivered in a vacuum but are interdependent on one another for optimal success, and this requires ongoing and effective communication among practitioners (Cox, 2019).

Although communication challenges can impede effective collaborative practices, more alarmingly they have been linked to patient harm . Suter et al. (2009) reported information from several sources stressing the potentially disastrous consequences of poor collaboration. The Canadian Medical Protective Association found patient safety was jeopardized by team discord and poor communication. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations reported that 65% of events resulting in patient death, permanent harm, severe temporary harm, or intervention required to sustain life were caused by failures in communication (The Joint Commission, 2017). Additionally, when poor communication practices inhibited the sharing of information, quality of care was diminished and patient outcomes were adversely affected (Suter et al., 2009). Although these reports are not specific to individuals with ASD, they illustrate the critical need for effective and efficient communication and the grave impact of conflict in collaboration.

Organizational Constraints

Interprofessional collaboration is often further hindered, or in some cases prevented, by the surrounding organization (Kvarnström, 2008; Strunk et al., 2017). In its authority, the organization may make changes to the interprofessional team by replacing or altering the number of team members, increasing client caseloads, modifying work schedules, or providing inadequate environmental conditions (Brown et al., 2011; Kvarnström, 2008). The team may then lack the appropriate professionals essential to effective client care and be deprived of the time needed for efficient communication and prompt conflict resolution (Brown et al., 2011; Kvarnström, 2008). These organizational constraints have the potential to invoke feelings of inadequacy, impede synergy, and obstruct quality client care. In many cases though, team members are practicing under separate organizations, and additional challenges concerning the lack of a shared organization hinder the team’s ability to collaborate completely.

Standards for the Transdisciplinary Collaboration of Professionals Treating Individuals With ASD

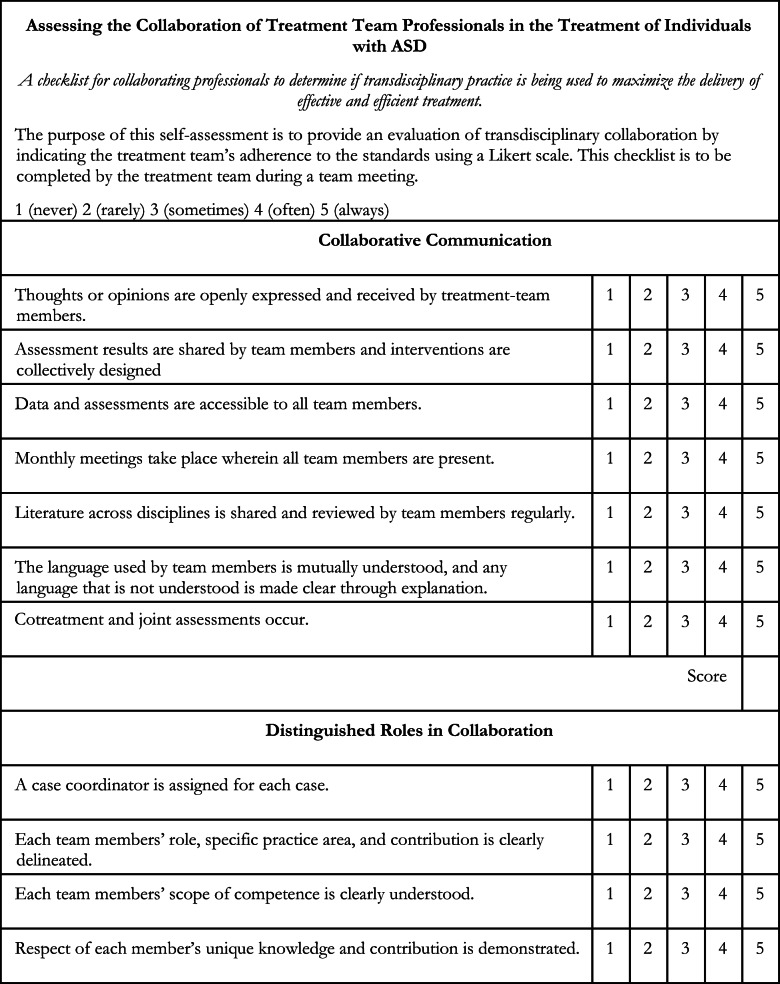

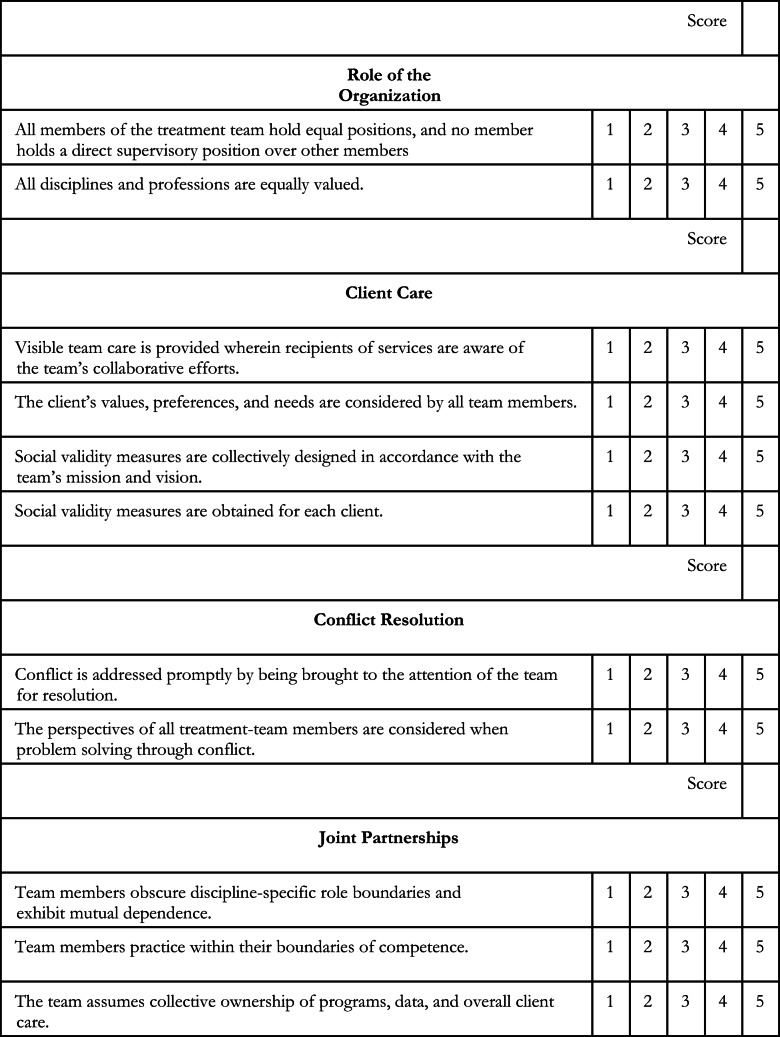

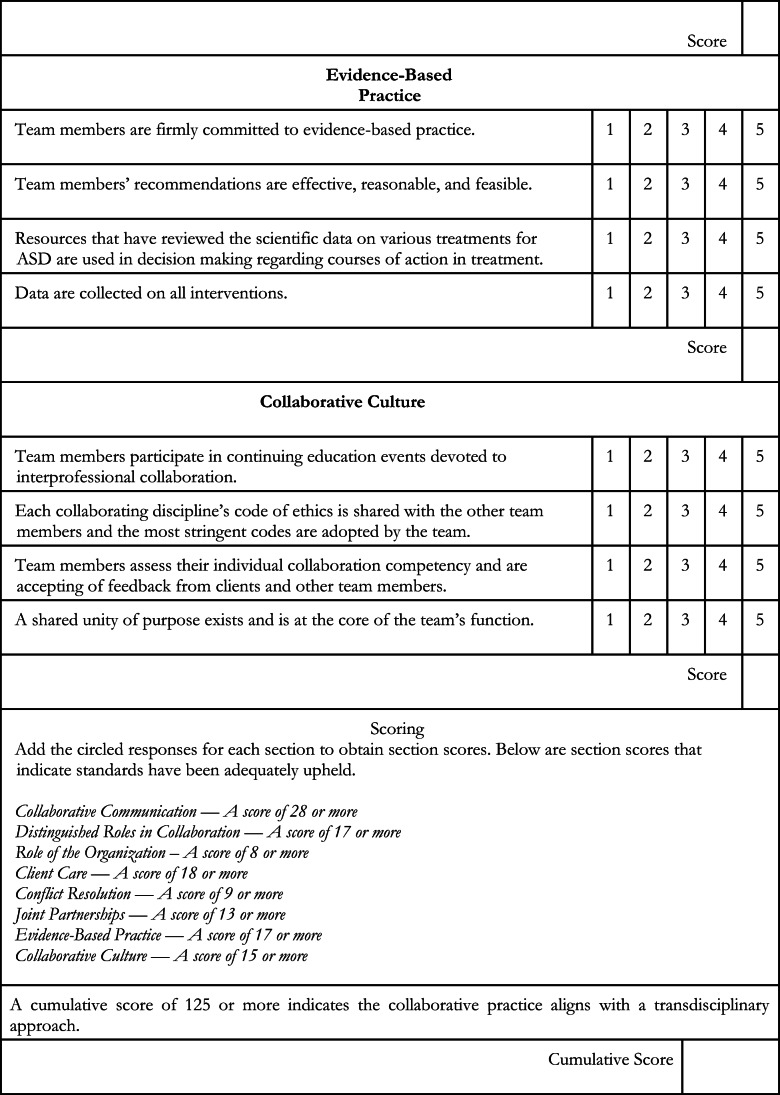

Given the plethora of existing barriers to effective integrated care and the limited training and education in collaborative practices, it is apparent that standards promoting a transdisciplinary model in the treatment of individuals with ASD may be beneficial. Many professionals recognize the potential advantages of interprofessional collaboration but are challenged with developing a cohesive approach. The standards provided in what follows are meant to help navigate the pitfalls observed in collaborative practice and ensure that the many benefits of transdisciplinary collaboration are realized. As D’Amour et al. (2005) noted, “it is unrealistic to think that simply bringing professionals together in teams will lead to collaboration” (p. 126). For this reason, the purpose of the proposed standards is to provide a set of guidelines for collaborative practice that promote appreciation of each discipline’s education and expertise and function to facilitate problem solving. The Appendix displays a self-assessment checklist that can be used by collaborating professionals to determine whether the proposed standards are being adequately upheld.

Preamble

These standards are intended to serve as a template for collaboration teams. Items should be added, omitted, extended, and modified in a manner that best serves the needs of the treatment team and facilitates effective collaborative practices. The contents are as follows:

-

Collaborative communication

1A.Open communication

1B.Sharing information

1C.Ongoing communication

1D.Active communication

1E.Informal communication

1F.Mutually understood language

-

Distinguished roles in collaboration

2A.Case coordinator

2B.Role delineation

2C.Respect of unique knowledge

-

Role of organization

3A.Necessary means

3B.Internal equality

3C.Professional environment

-

Client care

4A.Visible team care

4B.Client-centered care

4C.Social validity

-

Conflict resolution

5A.Timely resolution

5B.Bringing attention to conflict

5C.Perspectives within conflict

5D.Resolution protocols

5E.Involving clients

-

Joint partnerships

6A.Professional flexibility

6B.Interdependent practice

6C.Collective ownership

-

Evidence-based practice

7A.Treatment recommendations

7B.Comprehensive approach

7C.Reliance on data

-

Collaborative culture

8A.Collaborative education and training

8B.Ethics

8C.Self-assessment

8D.Unity of purpose

Expanded Standards

Collaborative communication

All team members should prioritize communication by ensuring it is open, frequent, and thorough, recalling that serious consequences of communication failures include client harm and interprofessional conflict. Should this standard be breached, the treatment team should have a discussion over the breaching, and aim to collaboratively develop a solution for the future.

1A. Open communication

-

i.Individual members must openly and respectfully communicate, with confidence and ease, expressing any thoughts or opinions spanning any relevant topic area (Coben et al., 1997). The team must encourage exchanges by actively listening. That is, team members must provide their full attention, refrain from interrupting, demonstrate understanding of their colleague’s perspective, and offer full consideration and appreciation of the contributions.1B. Sharing information

-

ii.

Each team member must be committed to effectively and deliberately sharing information, skills, expertise, ideas, responsibilities, and resources to integrate the contributions of all team members and provide the most effective client care (Bronstein, 2003; D’Amour et al., 2005; Hall, 2005; Lawson, 2004).

-

iii.

All team members, as well as clients and their families, must be actively involved in the planning and development of therapeutic goals. Team members must communicate deficits identified in their assessments, propose effective treatment options, and collectively design realistic, measurable goals that honor the client’s objectives and the team’s mission and shared vision (Bronstein, 2003).

-

iv.

Any intervention changes must be promptly communicated to all members of the collaboration team (Newhouse-Oisten et al., 2017).

-

v.

The reporting team member should describe any new intervention that is under consideration by stating the objectives or purpose of the intervention and indicating the extent of supporting scientific evidence (Newhouse-Oisten et al., 2017). Resources on the intervention should be shared with all team members.

-

vi.Information regarding client progress or relative setting events must be documented and communicated to all team members. Data should be reported in a central database, accessible to all members, and collectively analyzed and interpreted (Newhouse-Oisten et al., 2017).1C. Ongoing communication

-

vii.The collaboration team should establish opportunities for ongoing communication (Cox, 2019; Newhouse-Oisten et al., 2017). They should

- hold regularly scheduled meetings for all team members to occur no less than monthly (Newhouse-Oisten et al., 2017) and ensure that consistent scheduling is maintained to enable the participation of all members.

- schedule additional meetings as needed for select members according to client care needs. Meetings being held between select members should always include an invitation to all members of the team, even if their presence is not necessary.

- create an email group for regular and frequent exchanges regarding client updates, intervention changes, progress, and so on (Newhouse-Oisten et al., 2017).

- consider the development of an ongoing repository of all treatment information, including summaries of interprofessional meetings.1D. Active communication

-

viii.

Communication should take place within the context of direct clinical work, such as cotreating sessions and joint assessments with members from two or more disciplines (LaFrance et al., 2019).

-

ix.Team members should participate in team rounds regularly to discuss client progress and concerns and effectively coordinate client care (Suter et al., 2009).1E. Informal communication

-

x.The collaboration team should provide opportunities for informal exchanges of knowledge and information (LaFrance et al., 2019). They should

- hold in-service presentations and discussions hosted by each team member, on a rotating basis, representing the science of each discipline.

- schedule lunch meetings to encourage friendly interactions among members and allow the team to informally review and evaluate the successes and failures of collaboration (LaFrance et al., 2019).

- review journal articles selected by each team member, on a rotating basis, reviewing research from their respective field and allow for open discussion (LaFrance et al., 2019).1F. Mutually understood language

-

xi.

Professionals will use language that is mutually understood by all members of the treatment team and avoid the use of discipline-specific jargon (Boger et al., 2017; Cox, 2019; LaFrance et al., 2019).

-

xii.

Professionals will freely provide supplementary explanations when language is not understood by other collaborating professionals and will assess for mutual understanding throughout communication.

-

2.

Distinguished roles in collaboration

Team members should convey their clinical competencies and share their unique perspectives with team members. The discipline-specific skill sets and competence of team members are clearly outlined and respected, while input is considered from all team members. Should this standard be breached, the treatment team should have a discussion over the breaching by reviewing assigned roles. Moreover, the treatment team should aim to collaboratively develop a solution for the future by adjusting each member’s role as needed.

2A. Case coordinator

-

i.A role of case coordinator should be assigned to a separate member of the team for each case. The case coordinator will oversee the treatment plan, facilitate team rounds, coordinate communication among members, and aid conflict resolution when needed. The role of case coordinator may be assigned according to expertise, the client’s core deficit areas, and so on as deemed appropriate (Coben et al., 1997).2B. Role delineation

-

ii.

Team members must actively participate in decisions regarding role delineation on each case by conveying their scope of competence and how it may contribute to the team and the care of each individual client (Suter et al., 2009). For example, individual team members may have discipline-specific competencies that cannot ethically (or legally) be imparted to other individual team members. Thus, role delineation is not intended to be divisive, but rather ensure professionals practice within their scope of competence while feedback and input from other team members remain valuable.

-

iii.The delineation of each member’s case-specific role should be described within the treatment plan or a separate document if necessary and signed by each member of the treatment team in agreement.2C. Respect of unique knowledge

-

iv.

Professionals should avoid competitive pride and ambition and should be understanding of and interested in the value of other professionals’ unique knowledge within the collaborative team (Cox, 2012). In other words, collaborating professionals should engage in behavior that is indicative of their respect for the other team members’ unique knowledge, such as listening to suggestions and recommendations, being receptive to feedback, and asking for clarification when needed with the ultimate goal of synthesizing varying perspectives into a collective approach.

-

3.

Role of the organization

An organization should provide the needed support in collaborative practice and integrated care. Team members should share resources and benefits provided by the organization and rely on the organization for training, mediation, and protection. Should treatment team professionals not belong to a shared organization, this standard should be individualized to each professional’s respective organization.

3A. Necessary means

-

i.The organization should support the team by providing the necessary means for ongoing and effective collaborative practices (Suter et al., 2009). This may include

- staffing appropriate service providers.

- permitting conjoint treatment sessions.

- allowing time for meetings and interactions for all disciplines.

- providing physical space for collaboration.

- assigning an administrator to assist with clerical tasks and other logistical needs.

- assisting with timely conflict resolution when needed.

- offering professional development courses in interprofessional education.

- including collaboration in the mission of treatment, in initial training, and in ongoing professional development.

- encouraging research across disciplines, with each discipline controlling certain elements of the study as appropriate.

- encouraging clinical protocol development across disciplines, to address commonly encountered, complex problems in systematic and evidence-based ways.

- holding clinical rounds in which disciplines report on goals and progress.

- rotating journal clubs by discipline so that all members of the team are exposed to state-of-the-art knowledge across disciplines.

- holding professional development events for all staff with speakers from different disciplines.3B. Internal equality

-

ii.When possible, the organization will ensure that no member of the team holds a direct supervisory position over other members of the team and that all members assume equal positions within the company. Such equality will prevent multiple relationships on the interprofessional team that may inhibit open communication, shared responsibilities, and the actions of the case coordinator. If necessary, a within-discipline supervisor for each team member may be assigned to assist and serve as a resource in any cross-disciplinary issues.3C. Professional environment

-

iii.

The organization will foster an environment of professional equality where all disciplines and professionals will be equally valued. The organization must be mindful of ways that value may be measured and perceived by team members (e.g., wages, duties, opportunities, and attention) and work to ensure all professionals are respected and appreciated.

-

4.

Client care

The treatment team will prioritize client safety and access to effective, integrated care while encouraging and honoring client feedback. Should this standard be breached, the overall welfare of the client should be immediately assessed. If the breaching of this standard is found to impact the overall welfare of the client, or cause the client harm in any way, the intervention or professional known to be harmful should be immediately removed, and the team should work to ensure the client is kept safe.

4A. Visible team care

-

i.The team will provide “visible team care” (D’Amour et al., 2005). In other words, recipients of services will be aware of the collaborative efforts taking place “behind the scenes.” Collaborative practices will be fully transparent to promote client awareness of cohesive, integrated care. To do this, the parents/legal guardians of clients, or the clients themselves if of age, should be invited to team meetings, updated on collaborative discussions frequently, and involved in reviewing treatment plans and progress with multiple team members.4B. Client-centered care

-

ii.

The team will practice client-centered care by respecting the client’s values, preferences, and needs, as well as involving the client and family in shared decision making (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012; Bronstein, 2003; Garman et al., 2006).

-

iii.The overarching goal of the treatment team should be to ensure that direct recipients of services access the most effective treatments with minimal risk of harm. The treatment team should protect the client from any danger and advocate on behalf of the client for effective treatment and adequate care.4C. Social validity

-

iv.

Social validity measures should be collectively designed by the collaborative team in accordance with the team’s mission and vision. More specifically, social validity measures should be collected on the client’s experience receiving collaborative care, as well as on the collaborative team’s experience delivering collaborative care. As social validity measures are obtained for each client, the results should be reviewed and openly discussed during team meetings. Modifications to current collaborative practices should be made when necessary to ensure social validity.

-

5.

Conflict resolution

Any arising conflict should not impede the delivery of effective and efficient treatment. Collaborating professionals should avoid conflict by engaging in effective collaborative practices and exhibit professionalism in times of disagreement. Should this standard be breached, team members should problem solve quickly to develop a solution that is in the best interest of the client. Specifically, the assigned case coordinator should arrange for a team meeting wherein the conflict solutions are proposed.

5A. Timely resolution

-

i.Conflict must be recognized and addressed promptly. Due to its grave consequences, conflict cannot be avoided or ignored.5B. Bringing attention to conflict

- ii.

- iii.

- iv.

-

v.

Clients should not be involved in conflict resolution. The team is expected to maintain a unified appearance throughout client interactions. If a client’s perspective is needed to appropriately resolve conflict (e.g., opposing treatment recommendations), this should be done in the most professional manner and only after all team members have consented.

-

6.

Joint partnerships

Treatment team members should develop joint partnerships by engaging in close interactions, accepting shared responsibilities, and exhibiting trust and respect for all members of the team, their role, science, and discipline (D’Amour et al., 2005). All team members should value others’ unique knowledge base and encourage creativity. The treatment team should provide a work environment that promotes unity and fosters a culture of respect and ethical practice. Should this standard be breached, team members should have a discussion regarding the importance of joint partnerships within collaboration and work cooperatively to develop a plan that will encourage unity within the treatment team.

6A. Professional flexibility

-

i.

Professionals will demonstrate flexibility by obscuring the traditional role boundaries that typically exist between disciplines.

-

ii.

Members should extend their role by increasing their knowledge and skills within their respective fields, expand their role by learning from the other disciplines, and release their role by sharing their own expertise with other members (Thylefors et al., 2005).

-

iii.Professionals should engage in close interactions and accept joint responsibilities (D’Amour et al., 2005). Members should adapt under fluctuating conditions and the needs of interprofessional treatment by complementing other team members and adjusting to their strengths and weaknesses (Bronstein, 2003; Thylefors et al., 2005).6B. Interdependent practice

-

iv.

Members should abandon philosophies of autonomy and demonstrate a mutual dependence on one another to promote cooperative interactions and maximize client outcomes (Bronstein, 2003; Cox, 2019; D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005). Effective client care is obtained through collaborative practice when members rely on one another to fulfill their role and complete professional tasks (Bronstein, 2003; D’Amour et al., 2005; Thylefors et al., 2005).

-

v.

All team members should practice within their boundaries of competence and be transparent and honest when interventions or proposed treatments appear to be outside of one’s scope of competence.

-

vi.Members should be confident in their own role and the value they bring to the team and understand the role of other members and the benefit of their contributions (Bronstein, 2003).6C. Collective ownership

-

vii.

The team must assume collective ownership of all structures, programs, plans, tasks, goals, interventions, data, and overall client care (Bronstein, 2003; D’Amour et al., 2005). The decision making, problem solving, conflict resolution, accountability, philosophies, and values must be shared by all team members and require a joint undertaking as part of the collaborative process (D’Amour et al., 2005).

-

7.

Evidence-based practice

The team should be firmly committed to evidence-based practices and should openly renounce pseudoscience and reject those interventions that have proven to be harmful or ineffective. Should this standard be breached, or should a breach be suspected, the case coordinator should promptly schedule a meeting for team members to discuss existing literature on the proposed intervention and consider client values and context.

7A. Treatment recommendations

-

i.Individual team members must recommend treatments that (a) do not put the client in any danger and will not cause harm; (b) are empirically supported, financially reasonable, and easy to access; and (c) are effective, plausible, and feasible to adhere to. Should team members recommend treatments that do not meet the aforementioned criteria, a team meeting should be held wherein collaborative members review the intervention according to the specified criteria (see Brodhead, 2015). Ideally, members should unanimously consent to the recommendation. If members disagree, the reasons for rejection should be openly discussed. A time-limited pilot test of the intervention may be implemented, and continuation may be determined following thorough data analysis.7B. Comprehensive approach

-

ii.

Evidence-based practice will include using evidence provided by high-quality research, the professional expertise provided by the team members, and the values, needs, and preferences of the client (DiGennaro Reed et al., 2018).

-

iii.Although individual disciplines may adhere to differing levels of scientific evidence, the team as a whole must subscribe to standards of evidence that will be used to evaluate research studies.

- Research criteria for established interventions should include a thorough description of the treatment methods, a profile for each participant, and two randomized control trials or nine single-case research designs conducted across two or more research teams (DiGennaro Reed et al., 2018).

- The team should use resources such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses to review the available evidence on specific interventions. Other publications such as the National Standards Project by the National Autism Center at May Institute and the Evidence Maps produced by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association have assembled scientific data on various interventions and are intended to guide decisions for effective treatment.

-

iv.If an intervention with minimal empirical support has been identified as potentially beneficial, the team should become familiar with the treatment by consulting any corresponding position statements, reviewing available research, or discussing with team members and other experts (Brodhead, 2015). If evidence of harm is found, the intervention should not be used (Brodhead, 2015). If the treatment does not pose a risk to the client’s safety, the efficacy of the intervention may be evaluated through a single-subject research design within the context of treatment, wherein procedural and fidelity measures are operationally defined. The team should discuss the risks and potential benefits with the client, gather informed consent, implement appropriate data collection methods, and make treatment decisions following a thorough analysis of the data.7C. Reliance on data

-

v.

As scientists, team members should always yield to the data. Data should be collected on all interventions by the appropriate members of the team. Data should be analyzed frequently to assess client performance, and modifications to treatment programming should be made accordingly.

Collaborative Culture

The collaborative culture is created through the open communication, joint partnerships, and interdependent practice of the team members. It is rooted in a shared ethical code (Cox, 2012) and nurtured through frequent evaluation of integrated care and continuous education in collaborative practice. At the heart of the collaborative culture is the team’s unity of purpose, which explains the goals of the team and the reason for their existence (Lawson, 2004).

8A. Collaborative education and training

-

i.

The team should collectively engage in professional development devoted to client-centered care and interprofessional collaboration.

-

ii.

Members should read published articles in journals associated with the profession of other team members (e.g., speech-language pathology, ABA, medicine; Koenig & Gerenser, 2006).

-

iii.

Team members may attend professional conferences from other disciplines and encourage transdisciplinary presentations at such conferences.

8B. Ethics

-

iv.

Each member should publicly share their code of ethics, and all codes should be cross-referenced for commonalities and differences (see Cox, 2012). Although many codes will coincide, the differences will be noted, and the team should adopt and adhere to the most stringent codes to preserve unity within the team.

-

v.

Quarterly ethics-related professional development events should be used to increase understanding and facilitate discussion among team members.

8C. Self-assessment

-

vi.

Team members must assess their individual collaboration competency, accept feedback from clients and other team members, and use the information to improve their collaborative interactions and practices. To maintain the highest standards of practice, the team should conduct self-assessments of collaboration (see the Appendix).

-

vii.

The team will review client outcomes and social validity measures. If the results are not positive, the team must look to the collaborative processes (Kelly & Tincani, 2013).

-

viii.

Teams will also assess the degree of their collaborative practices and determine where they fall on the spectrum of interprofessional collaboration (Figure 1).

-

ix.

Teams should use additional assessment items, such as conflict resolution protocols and formal interprofessional rating scales, or a custom scale may be developed according to the standards for transdisciplinary collaboration.

8D. Unity of purpose

-

x.

The unity of purpose is a common purpose, shared by all team members, that cannot be successfully accomplished without true interdependence (Lawson, 2004). The unity of purpose should be at the core of the team’s function and may be illustrated in a mission statement: The mission of the transdisciplinary team is to produce measurable gains and maximize outcomes for individuals with ASD by combining and capitalizing on the expertise of multiple disciplines. To that end, we commit to function as a cohesive and collaborative unit, accentuating the strengths of our members, and sharing evidence from our respective sciences to provide superior integrated care.

Discussion

Although the proposed standards may promote more effective and efficient collaboration, there are potential limitations to the total use of them. First, the recommendations provided for the breaching of specific standards are brief. Additional recommendations regarding the most effective problem-solving strategies to be used in the event of breaching are needed and would be a valuable contribution. Second, adherence to the standards overall, especially pertaining to the role of the organization, may prove challenging, as treatment team members are frequently employed by separate and independent organizations. Thus, we recommend that interprofessional team members operate under a single organization wherein that organization values the collaborative efforts of the treatment team and provides additional support in achieving optimal integrated care. In this context, the use of the standards is likely to be more feasible. We challenge large organizations to consider the benefits of employing professionals from varying fields (e.g., medicine, psychology, speech, ABA) and facilitate a transdisciplinary approach.

Third, some of the proposed standards require that treatment team members spend additional time and effort to make collaboration successful. Therefore, it is important to identify ways in which professionals can be best motivated to achieve successful collaboration using the proposed standards. Moreover, collaboration is not universally taught to students of human service disciplines (see Kelly & Tincani, 2013); hence, many enter the workforce ill equipped to effectively engage in interprofessional collaboration. Within behavior analysis, students are largely trained to value and exude the worldview of radical behaviorism. At times, the adherence to this worldview may appear (to members of other professions) to diminish the contributions of other perspectives. Given this lack of training in collaboration at the education level, it is important to identify ways to develop repertoires that would increase the probability that team members will adopt the proposed standards.

In addition, the skills embedded in these standards are complex and need to be systematically defined and taught. It is our hope that discussing this as a goal across professions will lead to progress in the definition, refinement, and instruction of these skills. Within behavior analysis, attempts should be made to operationally define and measure these skills, use behavioral skills training or the teaching interaction procedure to teach practitioners these skills, and develop rubrics to assess the demonstration of these skills. Including collaborative competencies in the scope of training for behavior analysts would help ensure that new practitioners are familiar with and can demonstrate the essential component skills. Expanding the focus of training and supervision to include interprofessional collaboration would ensure that students and trainees in behavior analysis are coached in this crucial area well before they are expected to perform in transdisciplinary contexts. Indeed, other soft skills have recently been highlighted as relevant and essential for behavior analysts (e.g., compassionate care skills and cultural humility; Taylor et al., 2018; Wright, 2019). Finally, we recognize that these standards for effective collaboration may present as somewhat idealistic, but the hope is that they offer organizations and professionals a basis for developing cooperative partnerships that promote superior care and access to empirically supported interventions for individuals with ASD.

Conclusion

The prevalence rate of individuals diagnosed with ASD has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years, and at the time of this writing is currently 1 in 59 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). Therefore, the need for effective and efficient interprofessional collaboration is greater than ever and is gaining attention within the field of behavior analysis on both individual and organizational levels. For example, the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts enjoins cooperative interprofessional practice to appropriately serve clients (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2014, Section 2.03). The Behavioral Health Center of Excellence encourages interprofessional collaboration within their standards for accreditation as a high-quality, ethical, and efficacious applied behavior-analytic organization (Behavioral Health Center of Excellence, 2019). We contend that a transdisciplinary approach to collaboration affords treatment team members the opportunity to work together in creating the most meaningful change and greatest possible impact. The purpose of this article was to describe the current need for effective interprofessional collaboration and provide clear criteria that promote transdisciplinary care in the service provision for individuals with ASD. Other needed outcomes may be supported by the standards. For example, the impact of transdisciplinary practice on treatment gains could be explored in empirical research. Additionally, future research should investigate the components of the proposed standards and the effects of modifying the standards on the overall collaborative experience and client outcomes. The proposed standards for transdisciplinary treatment could also help in the creation of training modules in this important area, especially in the context of both academic course content and in the provision of supervised experience.

Appendix

Standards Adherence Self-Assessment Checklist

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Informed consent

Informed consent was not applicable as this review did not involve human participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article was composed to meet, in part, the requirements for a doctoral degree in applied behavior analysis at Endicott College.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Barry, M. J., & Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making—The pinnacle of patient-centered care. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 780–781. 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/BACB-Compliance-Code-english_190318.pdf

- Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. (2019). Standards for effective applied behavior analysis organizations.https://bhcoe.org/standards/

- Bennett E, Hauck Y, Radford G, Bindahneem S. An interprofessional exploration of nursing and social work roles when working jointly with families. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2016;30(2):232–237. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1115755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JH. Transdisciplinarity: A review of its origins, development, and current issues. Journal of Research Practice. 2015;11(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Boger J, Jackson P, Mulvenna M, Sixsmith J, Sixsmith A, Mihailidis A, Kontos P, Miller Polgar J, Grigorovich A, Martin S. Principles for fostering the transdisciplinary development of assistive technologies. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2017;12(5):480–490. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2016.1151953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT. Maintaining professional relationships in an interdisciplinary setting: Strategies for navigating nonbehavioral treatment recommendations for individuals with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):70–78. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0042-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein L. A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Social Work. 2003;48(3):297–306. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Lewis L, Ellis K, Stewart M, Freeman TR, Kasperski MJ. Conflict on interprofessional primary health care teams—Can it be resolved? Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2011;25(1):4–10. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.497750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio CJ, Woynaroski T, Baranek GT, Wallace MT. Toward an interdisciplinary approach to understanding sensory function in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research. 2016;9(9):920–925. doi: 10.1002/aur.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Data & statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- Choi BCK, Pak AWP. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 2006;29(6):351–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coben S, Thomas C, Sattler R, Morsink C. Meeting the challenge of consultation and collaboration: Developing interactive teams. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1997;4(30):427–432. doi: 10.1177/002221949703000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin A. Multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary collaboration: Implications for vocational psychology. International Journal for Educational & Vocational Guidance. 2009;9(2):101–110. doi: 10.1007/s10775-009-9155-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DJ. From interdisciplinary to integrated care of the child with autism: The essential role for a code of ethics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(12):2729–2738. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1530-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D. J. (2019). Ethical considerations in interdisciplinary treatments. In R. D. Rieske (Ed.), Handbook of interdisciplinary treatments for autism spectrum disorder (pp. 49–61). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-030-13027-5_4

- D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu M-D. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005;19(Suppl. 1):116–131. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGennaro Reed, F., Novak, M. D., Henley, A. J., Brand, D., & McDonald, M. E. (2018). Evidence based interventions. In J. B. Leaf (Ed.), Handbook of social skills and autism spectrum disorder (pp. 139-153). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-62995-7_9.

- Dillenburger K. The emperor’s new clothes: Eclecticism in autism treatment. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(3):1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillenburger K, Röttgers H-R, Dounavi K, Sparkman C, Keenan M, Thyer B, Nikopoulos C. Multidisciplinary teamwork in autism: Can one size fit all? The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2014;31(2):97–112. doi: 10.1017/edp.2014.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eikeseth S, Smith T, Jahr E, Eldevik S. Intensive behavioral treatment at school for 4- to 7-year-old children with autism: A 1-year comparison controlled study. Behavior Modification. 2002;26(1):49–68. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman AK, Tveit B, Sverdrup S. Leadership in interprofessional collaboration in health care. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2019;12:97–107. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S189199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garman A, Leach D, Spector N. Worldviews in collision: Conflict and collaboration across professional lines. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2006;27(7):829–849. doi: 10.1002/job.394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Murray A, Sohmer D, McClintock M, Conzen S, Olopade O. The importance of transdisciplinary collaborations for understanding and resolving health disparities. Social Work in Public Health. 2010;25(3):408–422. doi: 10.1080/19371910903241124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005;19(Suppl. 1):188–196. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JS, Sparkman CR, Cohen HG, Green G, Stanislaw H. A comparison of intensive behavior analytic and eclectic treatments for young children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;26(4):359–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JS, Stanislaw H, Green G, Sparkman CR, Cohen HG. Comparison of behavior analytic and eclectic early interventions for young children with autism after three years. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(12):3326–3344. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. (2017). Sentinel event policy and procedures. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_policy_and_procedures/

- Kelly A, Tincani M. Collaborative training and practice among applied behavior analysts who support individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2013;48(1):120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig M, Gerenser J. SLP-ABA: Collaborating to support individuals with communication impairments. The Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;1(1):2–10. doi: 10.1037/h0100180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kvarnström S. Difficulties in collaboration: A critical incident study of interprofessional healthcare teamwork. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2008;22(2):191–203. doi: 10.1080/13561820701760600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance, D., Weiss, M., Kazemi, E., Gerenser, J., & Dobres, J. (2019). Multidisciplinary teaming: Enhancing collaboration through increased understanding. Behavior Analysis in Practice.10.1007/s40617-019-00331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lawson HA. The logic of collaboration in education and the human services. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2004;18(3):225–237. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001731278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loseke D, Cahill S. Actors in search of a character: Student social workers’ quest for professional identity. Symbolic Interaction. 1986;9(2):245–258. doi: 10.1525/si.1986.9.2.245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon J, Cullinan V. Exploring eclecticism: The impact of educational theory on the development and implementation of comprehensive education programs (CEPs) for young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2016;32:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2016.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse-Oisten M, Peck K, Conway A, Frieder J. Ethical considerations for interdisciplinary collaboration with prescribing professionals. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10(2):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s40617-017-0184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck K, Mazur A. Behavior analyst use of and beliefs in treatments for people with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23(3):201–212. doi: 10.1002/bin.264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sims S, Hewitt G, Harris R. Evidence of collaboration, pooling of resources, learning, and role blurring in interprofessional healthcare teams: A realist synthesis. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2015;29(1):20–25. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.939745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk J, Leisen M, Schubert C. Using a multidisciplinary approach with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice. 2017;8:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2017.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suter E, Arndt J, Arthur N, Parboosingh J, Taylor E, Deutschlander S. Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2009;23(1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/13561820802338579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR. Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;12(3):654–666. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thylefors I, Persson O, Hellström D. Team types, perceived efficiency and team climate in Swedish cross-professional teamwork. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005;19(2):102–114. doi: 10.1080/13561820400024159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PI. Cultural humility in the practice of applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):805–809. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky B, Black L, Maenner M, Schieve L, Blumberg S. Estimated prevalence of autism and other developmental disabilities following questionnaire changes in the 2014 National Health Interview Survey. National Health Statistics Report. 2015;87:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]