Abstract

Catalytic hydrogen oxidation on a polycrystalline rhodium foil used as a surface structure library is studied by scanning photoelectron microscopy (SPEM) in the 10−6 mbar pressure range, yielding spatially resolved X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurements. Here we report an observation of a previously unknown coexistence of four different states on adjacent differently oriented domains of the same Rh sample at the exactly same conditions. A catalytically active steady state, a catalytically inactive steady state and multifrequential oscillating states are simultaneously observed. Our results thus demonstrate the general possibility of multi-states in a catalytic reaction. This highly unusual behaviour is explained on the basis of peculiarities of the formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen on differently structured Rh surfaces. The experimental findings are supported by mean-field micro-kinetic modelling. The present observations raise the interdisciplinary question of how self-organising dynamic processes in a heterogeneous system are influenced by the permeability of the borders confining the adjacent regions.

Subject terms: Chemical physics, Surface spectroscopy, Catalytic mechanisms

Catalytic reactions may exhibit oscillations in the reaction rate even at constant external parameters. Here, the authors observe and explain the coexistence of such oscillations and the steady states of catalytic activity in H2 oxidation on differently structured grains of a polycrystalline Rh foil.

Introduction

Spatiotemporal self-organisation may lead to spontaneous formation of patterns in many biological, chemical and physical systems far from equilibrium1. Such patterns have been observed for heart2 and brain tissues3, liquid crystals4, semiconductors5 and even for the geographical spread of pandemics6 or malware propagation7. In chemistry, apart from the well-known Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction8, a wide range of spatiotemporal dynamics has been observed in catalytic surface reactions, such as H2 and CO oxidation9. Steady-state patterns, travelling waves, moving pulses and oscillating patterns have been detected using surface microscopies, and modelled theoretically9–12. Usually, just one type of spatiotemporal behaviour is observed at a time, whereas a coexistence of both steady states and oscillations or travelling waves on the very same sample was not yet observed. However, using a polycrystalline Rh foil consisting of hundreds of µm-sized Rh(hkl) domains, multifrequential oscillations in catalytic H2 oxidation were previously detected: the reaction oscillated simultaneously on crystallographically different surface domains exhibiting different frequencies related to the domain structures13. On the nanoscale, this phenomenon was also visualised on a Rh curved crystal with the curvature in the range of 10−3 nm−1, allowing detection of the reconstruction-driven transition from synchronised to multifrequential oscillations along with entrainment, frequency-locking and collapse of spatial coupling14.

Using polycrystalline samples and curved crystals allowed establishing the surface structure library concept: surface processes are simultaneously monitored on crystallographically different µm-sized domains or nanofacets of the same sample15. This automatically allows identical reaction conditions for all crystallographic orientations, a condition which is hard to fulfil in a conventional “one sample after another” type of measurement16–18.

The advantages of surface structure libraries can be exploited only when spatially-resolving methods based on parallel imaging, such as photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM) or field emission/field ion microscopies (FEM/FIM), are applied19,20. A limitation with these techniques is that only the local intensity of the recorded image is analysed, whereas chemical sensitivity is lacking. This prevents a straightforward investigation of the atomistic mechanism of the observed effects. In contrast, SPEM, applied in the present work, can—besides imaging the sample surface with sub-micrometre resolution—chemically resolve the surface distribution of individual species via locally resolved XPS (see further details in the Methods section). The use of a technique with chemical information is essential when studying catalytic oxidation reactions on Rh, because the formation of subsurface oxygen and surface oxides may strongly obscure the reaction kinetics21.

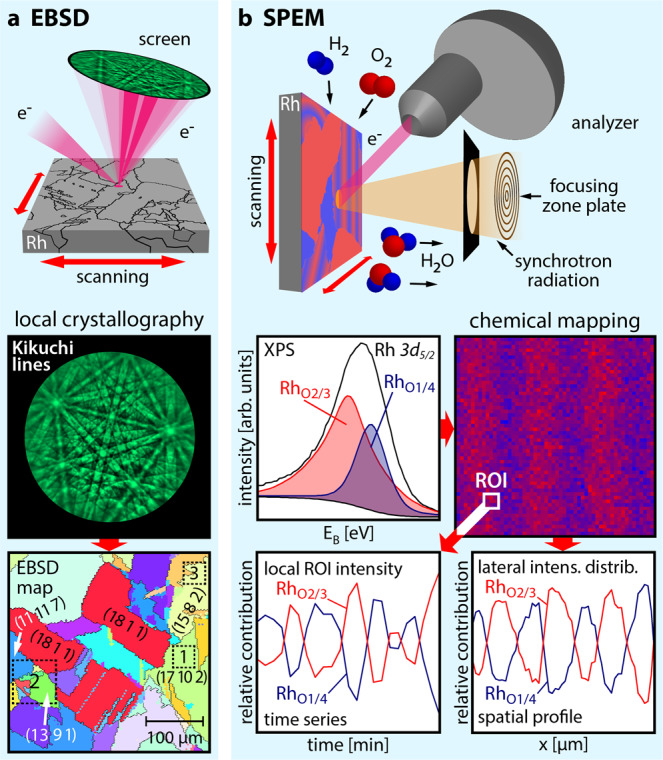

The experimental approach is illustrated in Fig. 1: the crystallography of each Rh(hkl) domain of the polycrystalline surface was characterised by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD; Fig. 1a, see further details in the SI). The ongoing catalytic H2 oxidation reaction was visualised in situ by SPEM (Fig. 1b), providing chemical maps, spatial profiles and time series of different spectral components.

Fig. 1. Experimental approach.

a EBSD: the backscattered electrons of a focused electron beam form Kikuchi lines on a phosphorous screen, enabling determination of the crystallographic orientation of each µm-sized Rh domain; the square regions marked in the EBSD map correspond to those shown in Fig. 2a (region 1) and Fig. 3a (regions 2 and 3); b SPEM: the Rh surface is in situ raster-scanned by a sub-µm-sized X-ray spot during H2 oxidation, with the emitted photoelectrons providing local XPS spectra. The local adsorbate coverage obtained from the XPS data is displayed as a chemical map. Real-time monitoring reveals both temporal and spatial periodicity of individual spectral components.

In the present work, catalytic hydrogen oxidation is studied by SPEM in the 10−6 mbar pressure range on a polycrystalline rhodium foil acting as a surface structure library. Due to the combination of chemical imaging and spatially resolved XPS measurements provided by SPEM, a coexistence of a catalytically active steady state, a catalytically inactive steady state and of multifrequential oscillating states on adjacent domains of the same Rh sample is observed for the first time. This unique behaviour is explained on the basis of the distinguishing behaviour of differently structured Rh surfaces with respect to the mechanism of the kinetic oscillations. The present findings support the formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen as a feedback mechanism for the observed kinetic oscillations. The experimental data are complemented by mean-field micro-kinetic modelling.

Results and discussion

Spectromicroscopy of kinetic oscillations

The experiments, in which the SPEM chamber was operated as a flow reactor in the 10−6 mbar pressure range, were performed at the “ESCA Microscopy” beamline of the Elettra synchrotron facility22.

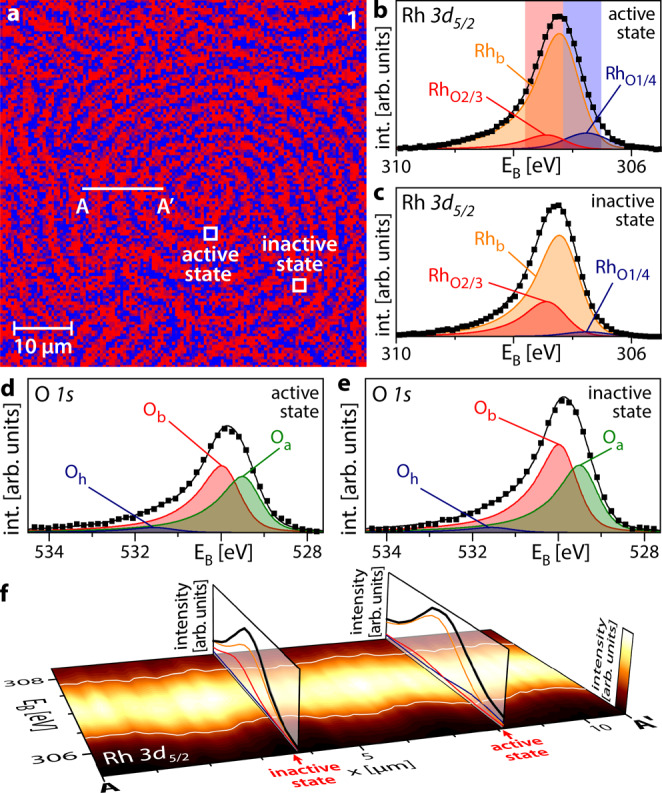

Figure 2a shows as an example the Rh 3d5/2 SPEM chemical map formed on the Rh(17 10 2) domain (cf. region 1 in the EBSD map in Fig. 1a) during oscillations at T = 453 K, pO2 = 1.1 × 10−6 mbar and pH2 = 1.2 × 10−6 mbar. The energy windows (blue and red shaded areas in Fig. 2b) for constructing the map were chosen to reflect different rhodium-oxygen-binding environments. Using reference spectra, these can be related to the state of catalytic activity, as detailed below: the red colour in Fig. 2a corresponds to a catalytically inactive state, while blue corresponds to a catalytically active state. Examples of Rh 3d5/2 spectra of both active and inactive surface regions marked in Fig. 2a are given in Fig. 2b, c, respectively.

Fig. 2. Oscillating pattern in H2 oxidation on Rh (T = 453 K, pO2 = 1.1 × 10−6 mbar, pH2 = 1.2 × 10−6 mbar).

a Rh 3d5/2 SPEM map of region 1 in Fig. 1a showing the distribution of 2/3 (red) and 1/4 (blue) oxygen-bound Rh states on the Rh(17 10 2) domain; b Rh 3d5/2 XPS spectrum corresponding to the catalytically active state. Rhb: bulk Rh; RhO2/3 and RhO1/4 correspond to Rh bound to oxygen; further details are given in the text. Squares: measured values; black solid line: sum of the deconvoluted components. The energy windows for constructing the SPEM map are shaded red and blue; c the same as in (b) but for the catalytically inactive state; d O 1 s XPS spectrum corresponding to the catalytically active state. Oa and Ob are associated with adsorbed atomic oxygen species, while Oh corresponds to the OH reaction intermediate. Squares: measured values; black solid line: sum of the deconvoluted components; e the same as in (d) but for the catalytically inactive state; f XPS spectral line profile along the line A-A′ marked in (a), with the colour code shown at the right edge. Vertical slices show exemplary spectra for the catalytically inactive and active states. The oscillating white lines serve as a guide for the eye.

Deconvolution of the spectra reveals three essential components: Rhb, related to bulk rhodium, and RhO2/3 and RhO1/4 which are related to Rh bound to oxygen. In the notation RhOi/j, i and j refer to the number of O atoms each Rh surface atom is bound to and the number of Rh surface atoms each O atom is bound to, respectively. The deconvolution procedure and notation are based on previous studies, reporting the Rh 3d5/2 spectral components characteristic for adsorption of oxygen on different Rh single crystal surfaces23–26.

The corresponding O 1 s spectra are shown in Fig. 2d, e, where Oa and Ob correspond to differently adsorbed oxygen species, while Oh belongs to the reaction intermediate OH27,28. In addition to varying amounts of different oxygen species, the total amount of oxygen (reflected in the total peak area) changes significantly between the two states.

Figure 2f illustrates, using colour-coded photoemission signal intensity, the oscillatory behaviour: the spectral line profile along the line A-A′ marked in Fig. 2a exhibits a sinus-like shape, with the white lines serving as a guide for the eye. Two vertical slices show examples of spectra characterising the catalytically active and inactive states. The switching between catalytically active and inactive states occurs via kinetic transitions, which resemble equilibrium phase transitions, due to the crucial role of cooperative phenomena29,30, but take place in a non-equilibrium thermodynamical situation1,31. Kinetic transitions in catalytic H2 oxidation on Rh were discussed in our previous work32.

Coexisting multistates

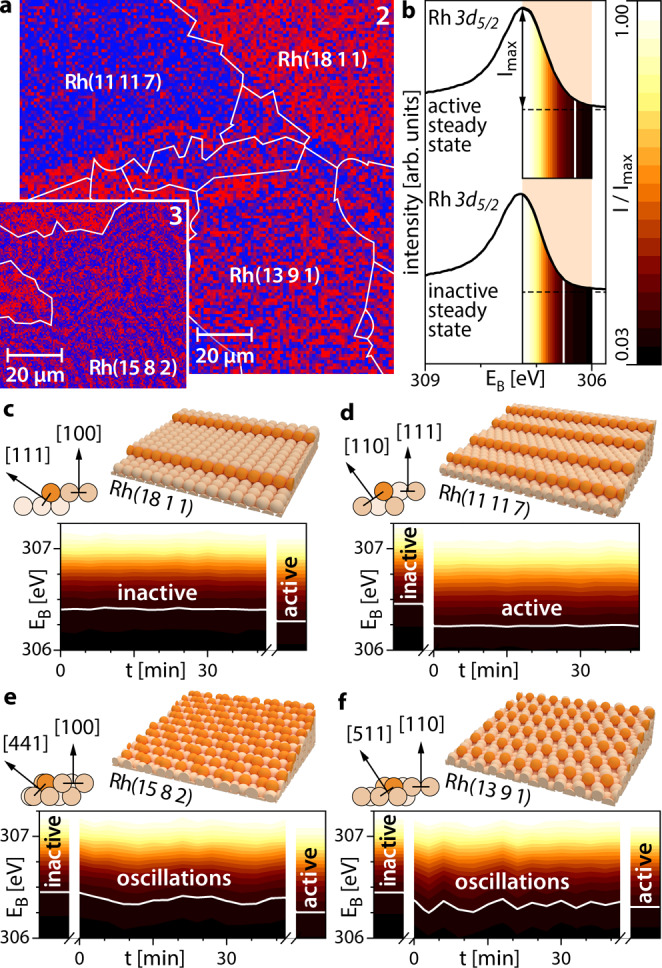

The use of a Rh surface structure library allows us to simultaneously visualise the ongoing reaction in situ on Rh(hkl) domains with different atomic surface structures. This is demonstrated in Fig. 3a with Rh 3d5/2 chemical maps constructed in the same way as in Fig. 2a, showing regions 2 and 3 from the EBSD map in Fig. 1a. The maps illustrate a unique situation, where different domains of the same sample (and thus at the exactly same p/T conditions) show oscillating patterns on Rh(15 8 2) and Rh(13 9 1), while the Rh(18 1 1) and Rh(11 11 7) domains appear to be entirely in the catalytically inactive and active steady states, respectively. Supplementary Video 1, created from consecutively obtained Rh 3d5/2 chemical maps of the Rh(13 9 1) domain, exemplarily shows the oscillating spatiotemporal patterns described above. Further details about the video are given in the SI.

Fig. 3. Coexisting multistates in catalytic H2 oxidation on Rh.

a Rh 3d5/2 SPEM map of 2/3 (red) and 1/4 (blue) oxygen-bound Rh states of regions 2 and 3 in Fig. 1a during H2 oxidation at T = 453 K, pO2 = 1.1 × 10−6 mbar, pH2 = 1.2 × 10−6 mbar; b reference Rh 3d5/2 XPS spectra for the catalytically active and inactive steady states on Rh(13 9 1) at T = 453 K, pO2 = 1.1 × 10−6 mbar, pH2 = 1.6 × 10−6 and 0.9 × 10−6 mbar, respectively. The XPS signal intensity in the energy window 306–307.25 eV is colour-coded; c atomic ball model of the Rh(18 1 1) surface and colour-coded spectral time series in the multi-state regime. The colour-coded active steady state reference spectrum from (b) is shown on the right hand side; d the same as in (c) but for the Rh(11 11 7) surface, with a reference spectrum of the inactive steady state on the left-hand side; e the same as in (c) but for the Rh(15 8 2) surface, with two reference spectra on both sides; f the same as in (e) but for Rh(13 9 1).

In order to assign the local XPS spectra of a particular domain to a specific state of catalytic activity, reference spectra for the catalytically inactive (at identical T = 453 K, pO2 = 1.1 × 10−6 mbar and pH2 = 0.9 × 10−6 mbar) and catalytically active steady states (at the same T and pO2 and pH2 = 1.6 × 10−6 mbar) were acquired for each of the studied domains. Reference Rh 3d5/2 spectra for Rh(13 9 1) are exemplarily shown in Fig. 3b with additionally colour-coded XPS signal intensity in the energy window from 306–307.25 eV.

Due to the temporal and spatial periodicity of the oscillation process, time series data can be used in addition to chemically resolved images to probe the oscillating spectral components. Representative spectral time series for the four Rh(hkl) domains mentioned above are shown in Fig. 3c–f using the same colour code for the XPS signal intensity as in Fig. 3b. For reference, spectra of the catalytically inactive and active steady states on the respective Rh(hkl) domain are shown on the sides of the spectral time series. The comparison of Fig. 3c, d again demonstrates that simultaneously some domains remain in the catalytically inactive (e.g. Rh(18 1 1)) or catalytically active (e.g. Rh(11 11 7)) steady states, while others oscillate with differing frequencies (e.g. Rh(15 8 2), f = 0.8 mHz; Rh(13 9 1), f = 2.4 mHz). To our knowledge, this behaviour, i.e. the simultaneous presence of oscillations and both steady states on the same sample at the exactly same external parameters, has not yet been observed for a catalytic surface reaction.

The multiplicity of states observed herein is, however, not a transient state that occurs only temporarily during a kinetic transition, but results from stationary patterns formed under reaction conditions as non-equilibrium (dissipative) structures33,34. Since the extension of patterns formed by adsorbates is confined by domain boundaries, such patterns can be treated solely as Turing-like and not as true Turing-structures possessing intrinsic dimensions35,36. In addition, the domain boundaries play the role of coherence terminators, disturbing the spatial coupling via hydrogen diffusion which provides the coherence of oscillations within individual domains. This leads to abrupt changes of the oscillation frequencies from one domain to another (frequency transforming) as previously observed13,37 or even to a full collapse of the entrainment of the oscillations and their termination as, e.g. in the case of the boundary between Rh(18 1 1) and Rh(13 9 1) visible in Fig. 3a.

This unique behaviour demonstrates the role of the catalyst surface structure in H2 oxidation, as illustrated by atomic ball models in Fig. 3c–f: Rh(18 1 1) and Rh(11 11 7), i.e. both domains in the steady state, exhibit step edges of a low-Miller-index type ([111] and [110]), whereas for both oscillating domains, i.e. Rh(15 8 2) and Rh(13 9 1), the step edges include kink sites. Although the presence of certain “atomic roughness” has been previously identified as a prerequisite for the occurrence of oscillations in H2 oxidation (oscillations do not occur on a smooth Rh(111) surface37), the present study reveals how the atomic structure of the step edges influences the behaviour of particular Rh(hkl) domains.

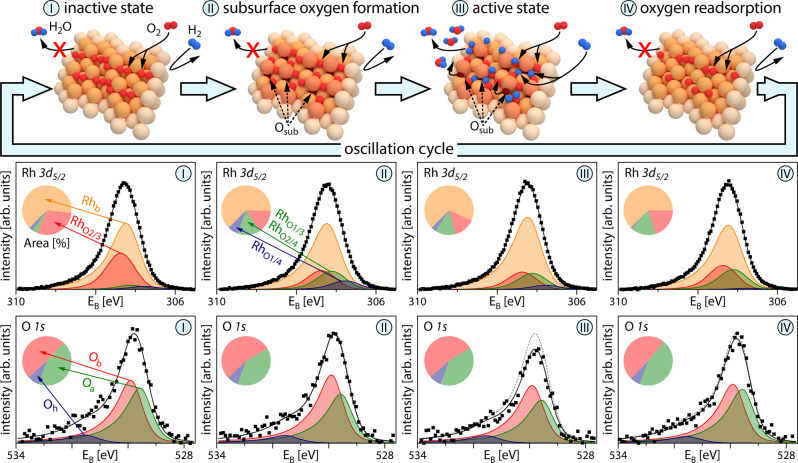

Insights into the feedback mechanism

The presence of coexisting multistates can be rationalised by considering the feedback mechanism governing the oscillations (Fig. 4). The top row in Fig. 4 shows ball models of the four stages of the oscillating cycle, while the middle and bottom rows display corresponding Rh 3d5/2 and O 1s XPS spectra acquired during a single cycle of the oscillations on Rh(15 8 2). As the particular atomic structure of Rh(15 8 2) exhibits occupancies of oxygen binding sites differing from those of the other studied surfaces, a fourth component containing RhO1/3 and RhO2/4, i.e. corresponding to another type of oxygen-bound Rh, was included in the Rh 3d5/2 spectra24. The pie diagrams show the respective peak area contributions.

Fig. 4. Oscillating components in catalytic H2 oxidation on Rh.

Upper row: schematic ball models of the four stages of the oscillation cycle, Osub indicates subsurface oxygen species; middle row: deconvoluted Rh 3d5/2 XPS spectra obtained during one cycle of oscillations on Rh(15 8 2). The Rhb component relates to bulk Rh, while the RhO2/3, RhO1/3/RhO2/4 and RhO1/4 components correspond to differently oxygen-bound Rh states; further details are given in the text. Squares: measured values; black solid line: sum of the deconvoluted components. The corresponding peak area contributions are given in the pie diagrams; bottom row: deconvoluted O 1s XPS spectra obtained during one cycle of oscillations. Oa and Ob components are associated with adsorbed atomic oxygen species, while Oh corresponds to the OH reaction intermediate. Squares: measured values; black solid line: sum of the deconvoluted components. The dashed grey lines in steps II–IV indicate the measured data from step I as a reference. The corresponding peak area contributions are given in the pie diagrams.

The Langmuir–Hinshelwood kinetics of catalytic H2 oxidation on Rh, including its oscillating mode, is primarily governed by the adsorption properties of the reactants oxygen and hydrogen38. The oscillation cycle starts from the catalytically inactive state (I), characterised by oxygen occupying primarily the energetically favoured threefold-hollow sites26. The higher binding energy of oxygen compared to hydrogen39 and preferential oxygen adsorption at the step edges40 hinder the dissociative adsorption of hydrogen on the step edges41, and thus catalytic activity. Due to the resulting dense oxygen coverage, oxygen atoms start to penetrate the Rh surface (stage II of the cycle). The process probably starts at a kink or edge sites which exhibit a larger structural flexibility42. While this can be considered the first step towards Rh surface oxidation, the resulting subsurface species should not be considered an ordered surface oxide, which is characterised by a far-ranging O-Rh-O trilayer structure and different XPS spectral signatures18. Following this incorporation of oxygen into the surface and the still dense oxygen coverage, some Rh atoms get slightly dislocated, increasing the local surface “roughness”41 and changing the binding geometry of adsorbed oxygen43. The changes in the binding geometry result in altered Rh 3d5/2 spectra, while the total amount of oxygen remains unchanged.

The increased surface “roughness” and the freed threefold-hollow sites create favourable conditions for the dissociative adsorption of hydrogen. Once enough hydrogen is available at the surface, a switch to the catalytically active state (III) takes place, where both hydrogen and oxygen adsorb dissociatively, and hydrogen can diffuse along the step edges and form water via an OH intermediate. This is reflected in a lower amount of oxygen-bound Rh and the corresponding diminished total peak area in the O 1s spectra. Eventually, also oxygen from subsurface sites will diffuse to surface sites and react. As a result, the rest of the adsorbed oxygen will switch back to the energetically more favourable adsorption sites and oxygen will once again be preferred at the step edges, resulting in a lack of hydrogen supply and the surface switching back to the catalytically inactive state. During the last stage (IV), oxygen at the surface is replenished and the cycle starts again.

Using this description, the peculiarities of the Rh(18 1 1) and Rh(11 11 7) surfaces can also be explained: as already mentioned, the Rh(18 1 1) surface has a relatively low amount of step edges ([111]-type). Due to the kinetic limitations for oxygen penetration into the subsurface40, the amount of subsurface oxygen is not sufficient to create surface conditions for dissociative hydrogen adsorption. This domain thus remains in an inactive state. On the contrary, the Rh(11 11 7) surface exhibits plenty of step edges of [110] type, which owing to their structure allow for dissociative hydrogen adsorption at the present conditions. As a result, the Rh(11 11 7) surface maintains its catalytically active state.

While previous studies have provided a few hints about the feedback mechanism based on the formation/depletion of subsurface oxygen13,37, the present observations by chemically sensitive SPEM yield the first spectroscopic confirmation of the validity of the subsurface oxygen model.

Micro-kinetic modelling

To provide a rationale for the observed phenomena, micro-kinetic model simulations based on the Langmuir–Hinshelwood mechanism of H2 oxidation on Rh were carried out. The present model version is a field-free-case adaptation of a model originally developed by McEwen et al. to simulate field-induced oscillations44,45. The adapted model has already been applied in our previous studies of H2 oxidation on Rh13,37. In order to account for the role of the step edges in the formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen, the present version was additionally modified to include two different types of sites, namely terrace and step edge sites. The terrace sites are characterised by a higher barrier for the formation and reduction of subsurface oxygen species than the step edge sites. We use the step density resulting from the crystallographic orientation to model the relation of amounts of the two types of sites. Further details on the micro-kinetic model and the used parameters are given in the SI.

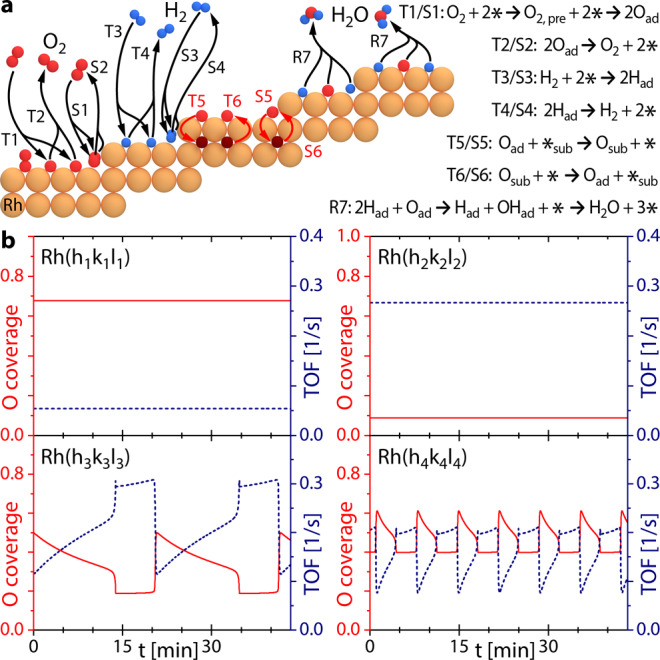

Figure 5a schematically depicts the reaction steps considered in the present model, where the letter T refers to terrace sites and the index S to step edge sites: the dissociative adsorption (T1/S1) and associative desorption (T2/S2) of oxygen and hydrogen (T3/S3 and T4/S4), formation (T5/S5) and depletion (T6/S6) of subsurface oxygen species and catalytic water formation (via an OHad intermediate) and desorption (R7). In contrast to hydrogen, dissociative adsorption of oxygen takes place via a molecular precursor state (T1/S1).

Fig. 5. Micro-kinetic simulations of coexisting steady states and oscillations in catalytic H2 oxidation on Rh(hkl) domains of different atomic structure for T = 453 K, pO2 = 1.1 × 10−6 mbar, pH2 = 1.2 ×10−6 mbar.

a Reaction steps of H2 oxidation on a stepped Rh surface included in the micro-kinetic model and corresponding reaction equations, the denominations T and S refer to terrace sites and step edge sites, respectively. The index ad indicates adsorbed species, while the index sub refers to subsurface species and * denotes an empty site; b calculated results of the oxygen coverage (red solid line, left ordinate axis) and reaction rate (TOF, blue dotted line, right ordinate axis) for four differently structured Rh surfaces.

Figure 5b presents the oxygen coverages and reaction rates (turnover frequency; TOF) calculated for the experimental conditions of Fig. 3 for four differently structured Rh(hkl) surfaces, as modelled by terrace and step sites with the corresponding step density. The top left panel shows the results for a surface having [100]-type terraces and 13% non-kinked [111]-type step edges (i.e. similar to the Rh(18 1 1) surface), the top right panel for [111]-type terraces and 39% non-kinked [110]-type step edges (i.e. the Rh(11 11 7) surface), the bottom left panel for [100]-type terraces and 23% highly kinked [110]-type step edges (i.e. the Rh(15 8 2) surface) and the bottom right panel for [110]-type terraces and 50% highly kinked [100]-type step edges (i.e. the Rh(13 9 1) surface). The results of the calculations simulate the experimental behaviour well: the realistic variations of the step density and different basic terrace (i.e. [100]-, [110]- and [111]-structured) and step edge types (i.e. kinked and non-kinked) is sufficient to generate multistates simultaneously present on the differently structured adjacent domains of polycrystalline Rh at identical external parameters.

In summary, the presented study provides an unambiguous demonstration of how the surface structure may influence the local catalytic performance of small surface areas on the very same sample. At certain reaction conditions, adjacent crystallographically different regions of a catalyst are able to coexist in multiple states of catalytic activity. In the present case of catalytic hydrogen oxidation on rhodium, all possible states, i.e. high activity, low activity and multifrequential self-sustained oscillations, were observed simultaneously for µm-sized differently oriented Rh(hkl) domains of a polycrystalline Rh foil. The structure-related peculiarities of the formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen were identified as the key factor for such unusual behaviour. Depending on the specific configuration of terraces and step edges, the rate of formation of subsurface oxygen can either hinder the dissociative adsorption of hydrogen (i.e. the surface is in the catalytically inactive state) on some surfaces or, on other surfaces, promote the hydrogen adsorption (i.e. yielding the catalytically active state). In the range of “intermediate” formation rates of subsurface oxygen, self-sustaining oscillations occur at the same conditions. The present observations support the formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen as a feedback mechanism, which governs the frequency of the oscillations. Mean-field micro-kinetic calculations within a model distinguishing between terrace and step edge surface sites, which differ in their adsorption properties and activation energies for the formation of subsurface oxygen, corroborate the experimental observations.

The observed multistates are made possible because the grain boundaries confining the individual domains are permeable for the propagation of reaction fronts, but still effectively attenuate the spatial coupling. Attenuation of coupling impedes the transfer of a particular state that prevails on one domain to the adjacent regions, i.e. it prevents entrainment effects. Such entrainment was e.g. observed on a curved crystal, where the crystal edges separating different facets are more permeable for reaction fronts than grain boundaries on a polycrystalline sample14. Stimulated by the present observations, the interdisciplinary question arises of how the characteristics of borders between adjacent regions, exhibiting different spatiotemporal behaviour, can influence the self-organising dynamic processes in a heterogeneous system.

Methods

Preparation and characterisation of the Rh sample

A polished Rh foil (10 × 12 mm², 0.2 mm thickness, 99.99% purity, MaTecK) was used as a polycrystalline Rh sample. The sample was cleaned in UHV by repeated cycles of Ar+ ion sputtering at 1 keV at 300 K, annealing to 1073–1173 K and consecutive chemical treatment in oxygen (pO2 = 5 × 10−7 mbar at 773 K) and hydrogen (pH2 = 5 × 10−6 mbar at 773 K). The cleanliness of the sample was verified before each experiment and post-experimental analysis routinely performed after SPEM experiments did not indicate any changes in the surface composition.

The foil temperature was measured by a Type K thermocouple spot-welded to its front and regulated by a PID controller within a window of typically 0.25 K. The gas-phase composition was monitored by a mass spectrometer and the reactant partial pressures were constant within measurement accuracy. Previous work has demonstrated the absence of measurable temperature and pressure gradients at the present conditions46,47.

Characterisation of the sample crystallography was performed by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), providing the crystallographic orientation of each µm-sized domain by scanning the sample surface with a focused electron beam and recording the diffraction patterns generated by the backscattered electrons. EBSD measurements were performed in a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 200 F) using standard EBSD conditions and evaluation procedures48, more details are given in the SI.

Spectromicroscopy of kinetic oscillations

The experiments on the kinetic oscillations of catalytic hydrogen oxidation on Rh were performed with the scanning photoemission microscope (SPEM) hosted at the “ESCA Microscopy” beamline of the Elettra synchrotron facility, which has been described in detail elsewhere22. The end station consists of three UHV sub-chambers: the sample is introduced to the system via a fast-entry load lock attached to the first chamber. Using magnetic transfer arms and wobble sticks, the sample can be transferred in UHV to a preparation chamber, which is equipped with facilities for Ar+ ion sputtering, annealing, high purity gas supply (H2: 99.999%, O2: 99.999%) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) for checking sample composition and cleanliness. Afterwards, the sample is transferred in UHV to the SPEM chamber. A zone plate optical system provides a small focused photon probe (spot diameter 0.13 µm) used to illuminate the sample surface, while the analysed surface region is selected by a piezo specimen positioning and scanning system. The emitted photoelectrons are collected within an 8 eV kinetic energy window by a hemispherical energy analyser equipped with a 48 channel detector.

The SPEM was operated in two modes: in the microspectroscopy mode, an XPS spectrum from a microspot on the sample surface was collected, while in the imaging mode, the sample surface was mapped by synchronised-scanning the sample with respect to the photon probe. In the imaging mode, a 48 points XPS spectrum covering the 8 eV kinetic energy window was recorded for each pixel in the image, allowing determination of the spatial distribution of different chemical species and removal of the topography contribution49, and thus creating chemical maps, spatial profiles and time series. A single pixel in a typical SPEM image in the present work takes about 0.05 s to obtain, i.e. the whole image takes below 5 min, while the high-resolution Rh 3d or O 1s spectra take less than 1 min. The overall energy resolution is 0.3 eV50. Due to the setup geometry, electrons emitted at an angle of 60° to the surface normal were registered. Spectra were taken at a photon energy of 652.75 eV and the energy scales were calibrated against the energy of the Au 4f7/2 peak with a binding energy of 84.0 eV. The absence of any drifts in photon energy and photon flux was verified by obtaining Ta 4f spectra of the chemically inert tantalum clips used for mounting the sample and by obtaining Au 4f spectra of a separate gold foil sample at regular intervals between the experiments.

All spectra in the present work are representative examples of the described states and were deconvoluted using a pseudo-Voigt line shape51 in combination with a Shirley background52. The spectral components are based on literature data (see above) and were refined by considering the whole ensemble of spectra, including reference spectra of all clean, catalytically active and catalytically inactive surfaces.

The micro-kinetic simulations

The micro-kinetic simulations were carried out using a model based on the Langmuir–Hinshelwood mechanism of H2 oxidation on Rh. The reaction network included the dissociative adsorption and associative desorption of hydrogen, dissociative adsorption of oxygen via a precursor state and associative desorption of oxygen, formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen and catalytic water formation. In order to account for the role of the step edges in the formation and depletion of subsurface oxygen, in the present model, a distinction was made between two different types of adsorption sites, namely terrace and step edge sites. Details of the model and of the calculations as well as the used calculation parameters are given in the SI.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (P 32772-N; M.R., G.R., Y.S., P.W. and J.Z.) and the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation HORIZON 2020 by the project CALIPSOplus (730872; P.W.).

Author contributions

A.S.-T. and M.S.-P. contributed to the EBSD characterisation. M.A., L.G., M.R., G.R., P.W. and J.Z. contributed the SPEM measurements. M.R. and H.G. contributed the micro-kinetic model simulations. G.R. and Y.S. supervised the experimental work and were involved in the analysis of the experimental data. M.R., G.R., Y.S., P.W. and J.Z. prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available as zipped folders of annotated HDF4 files and text files in a Zenodo repository under 10.5281/zenodo.553578753.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Prof. Gerhard Ertl on the occasion of his 85th birthday.

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-26855-y.

References

- 1.Nicolis, G. & Prigogine, I. Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems: From Dissipative Structures to Order through Fluctuations (Wiley, 1977).

- 2.Winfree AT. Chemical waves and fibrillating hearts: discovery by computation. J. Biosci. 2002;27:465–473. doi: 10.1007/BF02705042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao W, Wu J-Y. Propagating wave and irregular dynamics: spatiotemporal patterns of cholinergic theta oscillations in neocortex in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:333–341. doi: 10.1152/jn.00715.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki Y, et al. Large-scale self-organization of reconfigurable topological defect networks in nematic liquid crystals. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13238. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schöll, E. Nonlinear Spatio-temporal Dynamics and Chaos in Semiconductors (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001).

- 6.Malchow, H., Petrovskii, S. V. & Venturino, E. Spatiotemporal Patterns in Ecology and Epidemiology: Theory, Models, and Simulation (Chapman and Hall, 2008).

- 7.Kumari S, Upadhyay RK. Exploring the behavior of malware propagation on mobile wireless sensor networks: Stability and control analysis. Math. Comput. Simula. 2021;190:246–269. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaikin AN, Zhabotinsky AM. Concentration wave propagation in two-dimensional liquid-phase self-oscillating system. Nature. 1970;225:535–537. doi: 10.1038/225535b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs C, Hildebrand M, Volkening S, Wintterlin J, Ertl G. Spatiotemporal self-organization in a surface reaction: From the atomic to the mesoscopic Scale. Science. 2001;293:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1062883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ertl G. Reactions at surfaces: from atoms to complexity (Nobel lecture) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3524–3535. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff J, Papathanasiou AG, Kevrekidis IG, Rotermund HH, Ertl G. Spatiotemporal addressing of surface activity. Nature. 2001;294:134–137. doi: 10.1126/science.1063597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imbihl, R. in Handbook of Surface Science (eds Hasselbrink, E. & Lundqvist, B. I.) Ch. 9 (Elsevier, 2008).

- 13.Suchorski Y, et al. Visualizing catalyst heterogeneity by a multifrequential oscillating reaction. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:600. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03007-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suchorski Y, et al. Resolving multifrequential oscillations and nanoscale interfacet communication in single-particle catalysis. Science. 2021;372:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.abf8107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suchorski Y, Rupprechter G. Heterogeneous surfaces as structure and particle size libraries of model catalysts. Catal. Lett. 2018;148:2947–2956. doi: 10.1007/s10562-018-2506-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogel D, et al. Local Catalytic ignition during CO Oxidation on low-Index Pt and Pd surfaces: a combined PEEM, MS and DFT study. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:10041–10044. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel D, et al. The role of defects in the local reaction kinetics of CO oxidation on low-index Pd surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:12054–12060. doi: 10.1021/jp312510d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler P, et al. How the anisotropy of surface oxide formation influences the transient activity of a surface reaction. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:69. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotermund HH. Real time imaging of catalytic reactions on surfaces: past, present and future. Surf. Sci. 2009;603:1662–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suchorski Y, Rupprechter G. Catalysis by imaging: from meso- to nano-scale. Top. Catal. 2020;63:1532–1544. [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Oertzen A, Mikhailov AS, Rotermund HH, Ertl G. Subsurface oxygen in the CO oxidation reaction on Pt(110): experiments and modeling of pattern formation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:4966–4981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casalis L, et al. ESCA microscopy beamline at ELETTRA. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1995;66:4870–4875. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganduglia-Pirovano MV, et al. Oxygen-induced Rh 3d5/2 surface core-level shifts on Rh(111) Phys. Rev. B. 2001;63:205415. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustafson J, et al. Identification of step atoms by high resolution core level spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91:056102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.056102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baraldi A, et al. Spectroscopic link between adsorption site occupation and local surface chemical reactivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;93:046101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.046101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bianchettin L, et al. Surface core level shift: high sensitive probe to oxygen-induced reconstruction of Rh(100) J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:13192–13198. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comelli G, et al. Real-time X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of dissociative oxygen adsorption on Rh(110) Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996;261:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klikovits J, et al. Kinetics of the reduction of the Rh(111) surface oxide: linking spectroscopy and atomic-scale information. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:9966–9975. doi: 10.1021/jp0611875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlögl F. Chemical reaction models for non-equilibrium phase transitions. Z. Phys. 1972;253:174–161. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlögl F. What can we learn about dissipative structures by model reactions. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 1980;84:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prigogine, I. & Glansdorff, P. Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability and Fluctuations (Wiley, 1971).

- 32.Datler M, et al. Hydrogen oxidation on stepped Rh surfaces: µm-scale versus nanoscale. Catal. Lett. 2016;146:1867–1874. doi: 10.1007/s10562-016-1824-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turing AM. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1952;237:37. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolis, G. Introduction to Nonlinear Science (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995).

- 35.Kapral, R. & Showalter, K. (eds.) Chemical Waves and Patterns. (Kluwer Academic, 1995).

- 36.Schütz E, et al. Bimetallic catalysts as dissipative structures: stationary concentration patterns in the O2 + H2 reaction on a composite Rh(110)/Pt surface. Catal. Lett. 1999;63:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suchorski Y, et al. Surface-structure libraries: multifrequential oscillations in catalytic hydrogen oxidation on rhodium. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:4217–4227. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b11421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yates JT, Jr., Thiel PA, Weinberg WH. The catalytic reaction between adsorbed oxygen and hydrogen on Rh(111) Surf. Sci. 1979;82:45–68. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilke S, Natoli V, Cohen MH. Theoretical investigation of water formation on Rh and Pt Surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;112:9986–9995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klikovits J, et al. Step-orientation-dependent oxidation: from 1D to 2D oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:266104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.266104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Africh C, et al. Two-step reaction on a strained, nanoscale segmented surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;93:126104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.126104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Derouin J, Farber RG, Killelea DR. Combined STM and TPD study of Rh(111) under conditions of high oxygen coverage. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:14748–14755. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Köhler L, et al. High-coverage oxygen structures on Rh(111): adsorbate repulsion and site preference is not enough. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;93:266103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.266103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McEwen J-S, Gaspard P, Visart de Bocarmé T, Kruse N. Oscillations and bistability in the catalytic formation of water on rhodium in high electric fields. J. Phys. Chem. 2009;113:17045–17058. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McEwen J-S, Gaspard P, Visart de Bocarmé T, Kruse N. Nanometric chemical clocks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3006–3010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811941106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suchorski Y, et al. Local reaction kinetics by imaging: CO oxidation on polycrystalline platinum. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11:3231–3235. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spiel C, et al. Catalytic CO oxidation on individual (110) domains of a polycrystalline Pt foil: local reaction kinetics by PEEM. Catal. Lett. 2011;141:625–632. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Humphreys FJ. Grain and subgrain characterisation by electron backscatter diffraction. J. Mat. Sci. 2001;36:3833–3854. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gregoratti L, et al. 48-Channel electron detector for photoemission spectroscopy and microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2004;75:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeller P, et al. Scanning photoelectron spectro‐microscopy: a modern tool for the study of materials at the nanoscale. Phys. Status Solidi A. 2018;215:180308. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans S. Curve synthesis and optimization procedures for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Surf. Interface Anal. 1991;17:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shirley DA. High-resolution X-ray photoemission spectrum of the valence bands of gold. Phys. Rev. B. 1972;5:4709–4714. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkler, P. et al. Coexisting multi-states in catalytic hydrogen oxidation on rhodium - Supplementary Database 1. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.5535787 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available as zipped folders of annotated HDF4 files and text files in a Zenodo repository under 10.5281/zenodo.553578753.