Abstract

This study used an alternating treatments embedded within a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design to evaluate the effects of a stability ball chair on the on-task and in-seat behavior for three children with autism in a clinic setting. Results indicated increases for both in-seat and on-task behavior with the stability ball chair compared to a standard table chair, however, results varied across participants. On-task behavior had a greater increase across participants compared to in-seat behavior with the stability ball chair. Social validity results found that therapists had an overall positive view of stability ball chairs. This study provides clinicians with options for alternative seating to increase the on-task and in-seat behavior of children with autism. This study extends the use and evaluation of alternative seating, from typically studied settings and contexts, such as classrooms, to clinic settings with younger populations.

Keywords: Stability ball chair, Antecedent intervention, Alternative seating, On-task behavior, In-seat behavior

It is estimated that 1 in 59 children have an autism diagnosis, according to the Centers for Disease Control (2018). Thus, there is an increasing demand to tailor the environment of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to increase their engagement and on-task behavior. Behavioral concerns for children with ASD include difficulty sitting still, attending to tasks, and engaging with peers and instructors in a timely and appropriate manner (Bagatell et al., 2010). To prevent behavioral issues from impeding learning in an instructional setting, antecedent interventions, such as alternative seating, have been implemented to increase engagement and on-task behavior (Schilling & Schwartz, 2004; Stichter et al., 2009). Alternative seating, in particular the use of stability balls, has shown improvements for in-seat behavior within classroom instructional settings (Hoofman, 2018; Schilling & Schwartz, 2004). Schilling and Schwartz’s study (2004) examined the use of stability ball chairs with four children, ages 3–4 years old, with ASD in a preschool classroom. Using a single-subject withdrawal design, Schilling and Schwartz (2004) reported that all students demonstrated improvements in engagement and in-seat behavior with stability ball chairs. Social validity measures revealed strong social validity, as teachers reported a preference for the stability ball chair.

Although improvements in in-seat behavior and engagement while using alternative seating have been replicated, there are mixed results regarding social validity. Stability balls—just the ball with no base—have reported low social validity due to children engaging in distracting behaviors such as bouncing and moving around the classroom on the balls (Bagatell et al., 2010; Hoofman, 2018). Krombach and Miltenberger (2020) evaluated the effects of stability balls on four children, ages 4–12, attending and in-seat behavior receiving in-home ABA therapy. Using a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design results indicated the stability ball increased in-seat and attending behaviors for all participants and was chosen most often by three of four participants during the choice phase. Therapists reported low social validity as they considered it distracting and dangerous. Bagatell et al. (2010) also reported low social validity as they evaluated the effectiveness of stability ball chairs on the engagement and in-seat behavior of six boys with ASD in a kindergarten or first-grade classroom. The results presented in Bagatell et al. (2010) were inconsistent with Schilling and Schwartz (2004) and Krombach and Miltenberger (2020) as the stability ball chair had little effect on in-seat behavior with no positive effect on engagement.

This study expands upon previous settings and contexts of use for stability ball chairs to a clinical setting. This is one of the first studies to evaluate the use of stability balls chairs in a clinic-based setting that provides one on one instruction to children with ASD. Studying the use of stability ball chairs in a clinic setting is significant as children are often expected to sit and attend for extended periods to build skills and decrease problem behavior. In addition, this study differs from previous studies within the context of use, as the stability ball chairs were used during individualized (Schilling & Schwartz, 2004) one-on-one skill acquisition time for all participants, compared to group-circle time as in Bagatell et al. (2010). The alternating treatment with an embedded multiple baseline across participants design established experimental control as participants used both the standard chair and the stability ball chair during intervention, compared to previous studies that only used the stability ball during intervention (Bagatell et al., 2010; Krombach & Miltenberger, 2020; Schilling & Schwartz, 2004). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to address previous limitations by examining the use of stability ball chairs within a clinic setting for children with ASD. In addition, social validity measures were collected to determine if therapists found stability ball chairs feasible and effective.

Methods

Participants and Setting

This study included three children ages 4–8 years old. Participants were diagnosed with ASD and were receiving interventions at a private applied behavior analysis clinic. Participants were selected to participate based upon therapist recommendation. Inclusion criteria included being a client at the clinic and having difficulty staying seated and engaged during individual therapy. For each participant, parents and clinicians had concerns with their ability to sit and attend to tasks without engaging in maladaptive behaviors before the onset of the study.

Ben was 4 years old and had a diagnosis of ASD. He was receiving therapy at the clinic for a year at the onset of the study. He received therapy for 6 hrs per week and did not receive any other services. Ben’s verbal behavior skills fell in the range of a typical 4-year-old, as measured by the Promoting Emergence of Advanced Knowledge (PEAK) assessment (Dixon, 2014). Luke was 8 years old and had a diagnosis of ASD. He was receiving therapy at the clinic for 8 months at the onset of the study and received therapy for 12 hrs per week. His verbal behavior skills were at the level of a typical 8-year-old using the PEAK assessment (Dixon, 2014). Mark was 5 years old and had a diagnosis of ASD. He had received ABA therapy for over 2 years and was receiving 25 hrs of ABA therapy at the current clinic. Mark’s verbal behavior was assessed at a 3-year-old level using the Verbal Behavior Milestone Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP) (Sundberg, 2008). He was nonvocal and used an iPad and limited sign language to communicate.

Materials

A small standard table chair and stability ball chair were used during this study. The standard chair had four legs, was made of plastic, and was small enough that the participants’ feet touched the floor. The stability ball chair consisted of a 38-cm rubber stability ball stabilized upon a black base made from plastic that was 20 in wide from one side of the wheels to the other. The stability ball chair had two lockable rolling wheels and a 2 ft tall stable back piece.

Target Behaviors

In-seat

In-seat behavior, measured as percentage of intervals, was defined as placing any portion of the participants’ buttocks in contact with the seat portion of the chair or stability ball chair, with at least one foot in contact with the floor, and the base of the chair in contact with the ground (Krombach & Miltenberger, 2020).

On-task

On-task behavior, measured as percentage of intervals, was defined as the participant oriented towards the therapist or appropriate tasks and materials with appropriate interactions and responses with the materials and therapist (Hoofman, 2018). Participants were on-task when they followed through and acted in accordance with the therapist’s directive within 3-s of the directive being given. Participants were off-task when they were oriented towards other activities, items, and/or behaviors that did not coincide with the therapist’s directives (Krombach & Miltenberger, 2020). If a participant was told to sort shapes and was out of seat but still completed the task, they would be considered on-task but out of seat. If a participant was out of seat and did not follow the therapist’s directive, they would be considered off-task and out of seat.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

Data were collected using a 10-s whole interval sampling procedure for on-task behavior and in-seat behavior. Each session was 5 min in length throughout all phases and conditions of the study. The researcher sat in view of the participant and continuously recorded if the participant engaged in in-seat and on-task behavior for the entirety of each 10-s interval. A plus (“+”) was marked in the respective columns if the participant was on-task and/or in-seat for the entire 10-s interval, and a minus (“-“) was marked if they engaged in off-task behavior or left the seat.

A second observer independently collected the same whole interval data to calculate interobserver agreement (IOA). The secondary observer was trained, until mastery criteria of at least 80% agreement, by watching videos of children engaging in the target behaviors. Agreement was measured for each interval using a + or -. An agreement occurred when both data collectors marked a + or both marked a – for each interval. One data collector marking a + and the other marking a – indicated a disagreement. The formula to calculate IOA was number of intervals agreed/number of intervals agreed + number of intervals disagreed multiplied by 100.

IOA was collected for each participant in every condition. Ben’s IOA was calculated for 40% of all sessions, with an overall IOA of 83% (range = 73%–93%). Luke’s IOA was calculated for 43% of all sessions, with an overall IOA of 83% (range = 70%–97%). Mark’s IOA was calculated for 40% of all sessions, with an overall IOA of 84% (range = 73%–96%).

Experimental Design

An alternating treatments embedded within a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design was used to demonstrate experimental control. The alternating treatments phase included two conditions: standard table chair and stability ball chair.

Procedure

Therapists conducted all sessions during one-on-one instructional time at a table. Each participant’s therapist was the same across all sessions. If a participant tried to leave the table during the session, they were instructed to sit down and gesturally prompted to the seat if needed. If the participant engaged in out of seat behavior that did not result in them standing from the chair and trying to leave the area, they were not instructed to sit down.

Baseline

During the baseline phase, the therapist conducted the therapy sessions in their usual manner. Participants sat in a standard chair, and the therapist responded to appropriate and problem behavior according to each child’s behavior plan.

Intervention

During the intervention phase, the standard table chair and the stability ball chair sessions were randomly alternated. No more than two of the same condition were run consecutively. Before the first session within intervention, participants were instructed on how to properly use the standard chair and the stability ball chair. Therapists implemented behavioral skills training to teach the participants how to use both types of seating, including instructions, modeling, and feedback on how to sit correctly. Behavior skills training was conducted at least three times for at least 1 min, or until the participant sat correctly in each seat on three separate occurrences before the intervention was implemented. Participants were instructed to sit on each seat in accordance with the in-seat operational definition. The therapist modeled how to sit correctly and provided feedback and correction to the participant when they sat on each seat. Once the participant could sit appropriately, with their bottom on the standard chair and the stability ball chair with at least one foot on the ground, intervention started.

All sessions in the intervention condition were conducted in the same manner as the baseline condition. The only difference being the participant randomly alternated between the standard chair and the stability ball chair. Therapists continued to respond to appropriate and problem behavior as they typically would according to each child’s behavior plan.

Treatment integrity

Treatment integrity included the therapist: having the correct seating and materials for the sessions, instructing the student to sit on the correct seat at the beginning of the session, and presenting tasks for the participants to complete (Hoofman, 2018). At the end of the 5-min session, the therapist instructed the participant that the session was over. Treatment integrity was collected by the researcher monitoring the intervention for 44% of all sessions across participants and conditions. Treatment integrity was 100% throughout all phases of the study.

Social validity

Social validity was assessed using a 5-point Likert-type questionnaire provided to the therapists at the completion of the study. The questionnaire was adapted from Fedewa and Erwin (2011) and included questions addressing the effectiveness, feasibility, and usability of the stability ball chair intervention. There were six items on the scale, and it was anchored with a 1 (strongly disagree) and a 5 (strongly agree). Items scores were averaged for each participant’s therapist.

Results

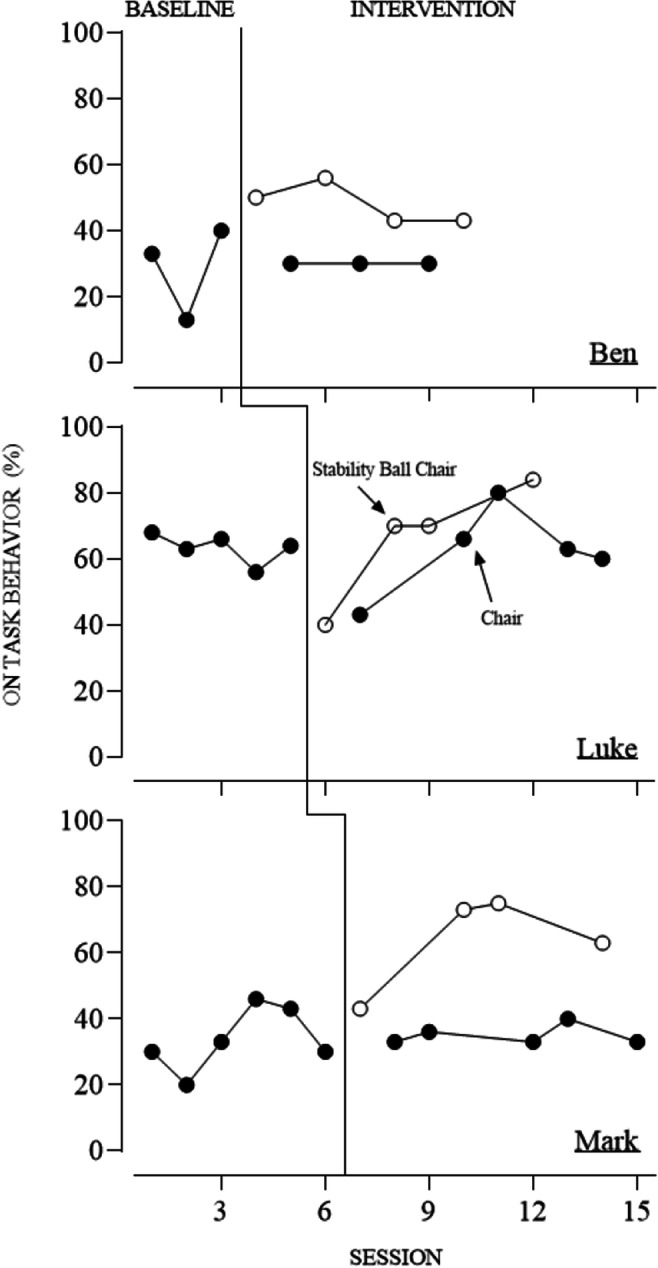

Figure 1 displays the in-seat data for all participants, whereas Fig. 2 displays the on-task behavior data. Ben’s in-seat behavior during intervention shows some overlap with baseline data and no consistent differentiation between conditions. In-seat behavior appeared variable and increased across both conditions. Ben’s on-task data demonstrated consistent differentiation between the two conditions in the intervention phase, with the stability ball chair resulting in higher levels of on-task behavior. Luke’s in-seat behavior showed a clear difference between the stability ball chair and the standard chair with no overlapping data points in the intervention phase. For Luke’s on-task behavior, only minimal differentiation occurred during the intervention phases with similar levels across both conditions. Mark’s in-seat behavior demonstrated a high degree of variability with both conditions demonstrating higher levels in the intervention phase with the stability ball chair higher towards the end of the phase. A clear and immediate difference was observed for Mark between the two conditions for on-task behavior with higher levels in the stability ball chair condition.

Fig. 1.

Overall percentage of in-seat behavior for all three participants

Fig. 2.

Overall percentage of on-task behavior for all three participants

Responses to the social validity scale revealed that therapists had an overall positive view of stability ball chairs within the clinic setting. See Table 1 for each therapist’s social validity scores. Therapists felt that stability ball chairs helped their clients focus on the task at hand (M = 3.7) while helping their clients with work completion (M = 3.7). Therapists also reported that clients could stay seated longer while staying on task with the stability ball chairs (M = 4) and listened and paid attention more when sitting on stability ball chairs (M = 3.7). Stability ball chairs were reported as great for providing clients with subtle physical activity while still allowing them to engage in work (M = 4.7). Therapists reported that they would use stability ball chairs instead of chairs for the majority of clinic work (M = 4.3) and having stability ball chairs in the clinic was fairly easy to manage as the therapist (M = 4.7).

Table 1.

Social validity measures with scores from each therapist

| Social Validity Measures | Ben’s Therapist | Luke’s Therapist | Mark’s Therapist |

| Stability ball chairs helped my client focus on the task at hand (seat-work, listening to directions, etc.) | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| My clients were able to stay “seated” longer while staying on task while using stability ball chairs | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Stability ball chairs helped my clients with work completion | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Clients listen and pay attention more when sitting on stability ball chairs | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| I would use stability ball chairs instead of chairs for the majority of clinic work | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Stability ball chairs are great for providing clients with subtle physical activity while still allowing them to engage in work | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Having stability ball chairs in the clinic was fairly easy to manage after clients and myself got accustomed to them | 4 | 5 | 5 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of stability ball chairs on in-seat and on-task behavior in a clinic setting. A secondary purpose was to examine the social validity of the use of stability ball chairs for clients by asking therapists to rate the ease of use and perceived effectiveness. Results revealed that the stability ball chairs yielded higher levels of in-seat behavior for Luke, with some evidence of increased in-seat behavior demonstrated with Mark. Results further demonstrated higher levels of on-task behavior with the stability ball chair for Ben and Mark, with some evidence for the same positive effect for Luke, but more data would have improved confidence in this claim. Unfortunately, there may have been some carryover between conditions in the intervention phase of the alternating treatments design for both Ben and Mark. There appeared to be an overall increase of in-seat behavior from baseline levels in the standard chair condition that mirrored the levels observed in the stability ball chair condition. Additional data points would have been helpful to determine if differentiation would occur as participants continued to use the different types of seating. It is interesting that treatment interference did not appear to occur for on-task behavior, because clear differences were observed between conditions. Experimental control was still obtained via the use of the multiple baseline across participants’ design.

The oldest participant Luke had the greatest increase in in-seat behavior when using the stability ball chair compared to the standard chair. In-seat data may have been more variable for Ben and Mark because, at times, they appeared distracted by other children playing nearby, which could have resulted in some of the variability observed across all phases of the study. Limitations to this study include the relative lack of control in clinics, such as other children’s actions in the clinic. This lack of control might contribute to some of the variability observed across conditions. However, it is important to note that these are the types of conditions that exist in typical clinic settings. Therefore, this study reflects the real-world application and results of alternative seating in a clinic setting for practitioners.

Social validity measures indicated that the therapist’s felt the stability ball chairs helped the participants increase their in-seat and on-task behavior. This differs from previous findings as both the Hoofman (2018) and Krombach and Miltenberger (2020) studies indicated low social validity with regular stability balls. This might indicate that a base where wheels can be locked to keep it stationary and prevent bouncing around might be more feasible to use in various settings.

The evidence from this study, when evaluated in coordination with results from previous studies within the literature, suggests that alternative seating can be used as an antecedent manipulation to positively affect behavior, such as a child’s on-task or in-seat behavior, across settings. This study evaluated a novel form of alternative seating, stability ball chairs, in a setting that had not been extensively explored, a clinic, and found varied support for the stability ball chair across participants and behaviors. This study was conducted at the end of the school year; therefore, researchers had a limited time to collect data prior to summer break. If the authors had additional time to continue the intervention phase, further conclusions might have been made about the results and data trends.

Further research should examine how alternative seating can be used in other settings where children are required to sit and complete work, whether in academic, clinical, or home settings. Studies might also evaluate how age or level of functioning might affect results and determine if other types of alternative seating produce positive results in clinic settings such as stability stools and scoop rocker chairs. For practitioners interested in incorporating alternative seating into their practice to improve on-task or in-seat behavior, they should consider all types of alternative seating and the associated cost. Clinics might consider purchasing only one of each type of alternative seating so that therapists can test to see which type of seating is the most effective and preferred by each child prior to purchasing seating for every child. To conclude, this study provided an extension of previous research by demonstrating that alternative seating can be an effective antecedent intervention for children with ASD in a clinic setting.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study that involved human participants were in accordance with the institution’s ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for participation in this research.

Footnotes

Utility of Work for Clinicians

• Provides options for alternative seating for clients within a clinic setting

• Evaluates how to increase the in-seat behavior of kids with autism

• Evaluates how to increase the on-task behavior of kids with autism

• Extends the use of alternative seating from common settings, such as classrooms with older populations, to clinic settings with younger populations

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Justine Brennan, Email: justinebrennan98@gmail.com.

Kimberly Crosland, Email: crosland@usf.edu.

References

- Bagatell N, Mirigliani G, Patterson C, Reyes Y, Test L. Effectiveness of therapy ball chairs on classroom participation in children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010;64(6):895–903. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2010.09149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder: Data and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- Dixon, M. R. (2014). The PEAK relational training system: Direct training module. Shawnee Scientific Press.

- Fedewa, A. L., & Erwin, H. E. (2011). Stability balls and students with attention and hyperactivity concerns: Implications for on-task and in-seat behavior. American Journal of Occupational Therapy,65(4), 393–399. 10.5014/ajot.2011.000554. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoofman, J. (2018). Effects of alternative seating on children with disabilities. [Unpublished master's thesis]. Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida.

- Krombach T, Miltenberger R. The effects of stability ball seating on the behavior of children with autism during instructional activities. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2020;50(2):551–559. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling D, Schwartz I. Alternative Seating for young children with autism spectrum disorder: Effects on classroom behavior. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2004;34(4):423–432. doi: 10.1023/B:JADD.0000037418.48587.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stichter J, Randolph J, Kay D, Gage N. The use of structural analysis to develop antecedent-based interventions for students with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(6):883–896. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, M. L. (2008). VB-MAPP verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: A language and social skills assessment program for children with autism or other developmental disabilities. AVB Press.