Abstract

Caregivers of children with an autism spectrum disorder are often responsible for assisting their children to complete activities of daily living skills. Effective and efficient caregiver training methods are needed to train caregivers. The present study used two concurrent multiple-baseline across-participants designs to evaluate the effects of real-time feedback and behavioral skills training on training eight caregivers to implement teaching procedures for activities of daily living skills with their child. We assessed caregivers’ accuracy and correct implementation of the six-component teaching procedure after they received either real-time feedback or behavioral skills training. Caregivers from both groups mastered and maintained correct implementation of the teaching procedures with their child. The overall results suggest that real-time feedback and behavioral skills training are efficacious to train caregivers to implement activities of daily living skills procedures with their children, and that real-time feedback may be an efficient alternative method to train caregivers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40617-020-00513-z.

Keywords: Real-time feedback, Caregiver training, Activities of daily living skills, Behavioral skills training

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) appears in childhood and is a disorder that affects development in social behavior, communication, and adaptive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In a recent study, more than half of the participants with a diagnosis of ASD were classified as having a daily living skills deficit (Duncan & Bishop, 2015). Activities of daily living skills (ADLS) are functional tasks that individuals complete every day, such as getting dressed, preparing food, and participating in leisure and work activities (Matson, Hattier, & Belva, 2012). Day-to-day functioning requires individuals to perform these activities independently; however, due to deficits associated with ASD, caregivers often assist or complete these tasks for their children.

If a child with ASD does not acquire independence in completing ADLS, then caregivers may continue to complete these activities throughout the individual’s adulthood (Duncan & Bishop, 2015). The child’s dependence on their caregiver to complete ADLS affects the caregiver’s productivity and can result in unemployment and loss of income depending on the needs of the child (Ganz, 2007). The lack of independence of the child can lead to residential placement, or the individual may require ongoing assistance as an adult, and thus societal costs of caring for and treating the individual are incurred (Carothers & Taylor, 2004; Ganz, 2007). However, teaching children with ASD to perform ADLS independently at an early age can lead to improved independence long term, which may increase future opportunities to obtain employment and live on their own and potentially reduce financial hardships on caregivers.

When teaching ADLS, implementation of efficacious teaching procedures is necessary for individuals with ASD to acquire independence in performing ADLS (Donnelly & Karsten, 2017; Grow et al., 2009). Errors while implementing teaching procedures can result in further delays of the child acquiring the ADLS and disrupt their performance on previously acquired ADLS. Thus, training caregivers of children with ASD to implement efficacious ADLS teaching procedures with integrity by using an efficient caregiver training method is essential to improve their child’s outcomes.

Behavioral skills training (BST) is an evidence-based method of teaching caregivers how to implement various behavioral interventions with children with ASD (Crockett, Fleming, Doepke, & Stevens, 2007; Miles & Wilder, 2009; Seiverling, Williams, Sturmey, & Hart, 2012). Although BST is an efficacious method for training caregivers, the package includes a number of training components, some of which may be unnecessary and may result in extended caregiver training time and sessions. Caregivers have household, community, and work responsibilities that may interfere with their participation in caregiver training, especially if training requires multiple sessions and several hours to master the intervention. Typical BST packages take 60 min to 13 hr to implement (Dogan et al., 2017; Hassan et al., 2018; Miles & Wilder, 2009); therefore, identifying which components of BST are most efficient and efficacious is imperative to the caregiver’s participation and accurate implementation of an intervention.

Studies have shown that using training packages with modified or combined components of BST is also successful in teaching caregivers to implement behavioral interventions with their children (Feldman et al., 1992; Wahler, Vigilante, & Strand, 2004). However, few studies have evaluated which specific components of BST are necessary (Lerman, Swiezy, Perkins-Parks, & Roane, 2000; Shanley & Niec, 2010; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012). In an attempt to address the cost-effectiveness of caregiver training, Lerman et al. (2000) evaluated the effectiveness of verbal and written instructions to train caregivers to implement behavior management strategies. The verbal and written instructions were ineffective for caregivers to implement all behavior management skills correctly. However, when caregivers received verbal feedback, they made immediate improvements in their implementation of the behavior management skills.

Only one known study has conducted a component analysis of BST by training teachers to conduct a functional analysis of problem behavior (Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012). In baseline, the teachers reviewed written instructions on how to conduct a functional analysis of problem behavior. Then the teachers received training on each functional analysis condition, which was paired with either modeling, rehearsal, or written and verbal feedback. Written and verbal feedback, as well as feedback combined with any other BST components, resulted in improvements in the teachers’ implementation of functional analysis procedures.

A more recent study evaluated the efficacy of feedback alone to train four clinical staff to implement a preference assessment with a child with ASD via telehealth (Ausenhus & Higgins, 2019). The researchers provided real-time feedback in the form of constructive feedback for preference assessment components implemented incorrectly and behavior-specific praise for corrected components that were previously conducted incorrectly. The real-time feedback resulted in an immediate increase in the staff’s correct implementation of preference assessment components to mastery levels, and the total duration of training sessions ranged from 31.1 min to 46.0 min across staff. These three studies provide preliminary evidence that feedback is a critical component of training (Ausenhus & Higgins, 2019; Lerman et al., 2000; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012); however, additional research is needed to determine the extent to which feedback alone (i.e., real-time feedback) is efficacious in training caregivers to teach and implement ADLS with their child.

Procedures for teaching ADLS tend to be more complex than discrete-trial instruction, as ADLS are behavior chains that consist of multiple steps (Donnelly & Karsten, 2017). ADLS typically require the child to engage in multiple complex motor movements and manipulation of materials to complete the skill, and the teaching of these skills typically necessitates prompts and prompt fading. Despite the complexity of teaching ADLS, studies demonstrate that individuals with disabilities can acquire ADLS with task analyses, chaining procedures, and effective prompting procedures (Demchak, 1990; Horner & Keilitz, 1975; Matson, Taras, Sevin, Love, & Fridley, 1990).

When teaching a behavior chain, the literature suggests that both forward and backward chaining procedures are efficacious (Slocum & Tiger, 2011; Walls, Zane, & Ellis, 1981; Weiss, 1978), and there are no differences in the number of trials to mastery or child preference for either procedure (Slocum & Tiger, 2011). However, the instructor prompting the child through the remaining steps of the chain (i.e., guided completion of the nontraining steps) after teaching the training step with a forward chaining procedure can reduce the number of teaching trials to mastery (Bancroft, Weiss, Libby, & Ahearn, 2011). Additionally, employing most-to-least prompting with a constant prompt delay to teach complex chains can reduce response errors, provide opportunities for the child to respond independently, and systematically fade prompts to circumvent the child’s dependence on prompts (Libby, Weiss, Bancroft, & Ahearn, 2008; MacDuff, Krantz, & McClannahan, 2001).

Studies have shown that errors in teaching behavior chains can impair the child’s acquisition of ADLS and result in poorer maintenance (Donnelly & Karsten, 2017; Grow et al., 2009). Therefore, training caregivers to use effective teaching procedures with integrity to teach ADLS to children at an early age can reduce delays in the child acquiring crucial skills. Limited research exists on training caregivers to teach ADLS to their young children with ASD (Gruber & Poulson, 2016). Currently, no research exists on the effectiveness of using BST to train caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures with their children—specifically, forward chaining procedures using a constant prompt delay with most-to-least prompting and guided completion of the nontraining steps in the behavior chain. Not all components of BST may be necessary to train caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures. Written instructions, modeling, and rehearsal are antecedent strategies that may function as discriminative stimuli for caregivers to implement intervention procedures correctly (Miltenberger, 2012), whereas feedback may function as a reinforcing consequence on the caregiver’s response during rehearsal.

Real-time feedback immediately specifies the behaviors performed correctly (i.e., behavior-specific praise) or provides verbal instructions following an error response (i.e., corrective feedback; Ausenhus & Higgins, 2019). Real-time feedback, as a consequence, includes the modeling and verbal instruction components of BST during rehearsal. Therefore, feedback alone (i.e., real-time feedback) may be an efficacious and efficient alternative for training caregivers to implement behavioral interventions with their child with ASD. No known studies have conducted an evaluation of training caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures with real-time feedback or an efficiency evaluation of BST in comparison to a single training component of BST (i.e., real-time feedback). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and efficiency of the use of BST and real-time feedback to train caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures with their young children with ASD. We also sought to measure the social validity of BST and real-time feedback to determine the acceptability of the training procedures.

Method

Participants, Setting, and Materials

We recruited eight caregiver–child dyads receiving early intensive applied behavior-analytic services from a university-affiliated clinic. The caregivers were parents of the child participants; caregivers included six females and two males whose ages ranged from 27 to 46 years (M = 34). All the caregivers reported no previous participation in caregiver training targeting ADLS. The child participants included one female and seven males whose ages ranged from 3 to 5 years (M = 4). The child participants had a diagnosis of ASD and had attended the early intensive applied behavior-analytic clinic for 3.5 to 28 months (M = 11). All child participants performed less than 50% of the steps independently for handwashing and putting on a jacket during the child baseline probes conducted prior to the study.

We randomly assigned caregiver–child dyads to the real-time feedback or BST group, and each group included three female and one male caregiver. The real-time feedback caregiver–child dyads included Allan–Andy, Betty–Brice, Cindy–Caleb, and Dana–Danny. Andy and Caleb communicated with speech-generating devices, Brice communicated vocally with two- to three-word mands, and Danny communicated vocally with three- to five-word mands. The BST caregiver–child dyads included Emily–Ella, Fran–Frank, Gary–Gabe, and Helen–Henry. Ella communicated with a picture-exchange system, Frank and Henry communicated with speech-generating devices, and Gabe communicated vocally with one- to two-word mands. All child participants tolerated physical prompts and engaged in low rates of challenging behaviors at the clinic and at home.

Caregiver baseline probes, intervention sessions, and generalization and maintenance probes for handwashing and putting on a jacket were conducted with all caregiver–child dyads in a private bathroom and treatment room at the clinic. All caregiver–child dyads were assigned handwashing as the primary ADLS, and caregivers received training on how to teach handwashing to their child during intervention sessions. All caregiver–child dyads were assigned putting on a jacket as the generalization skill conducted in the clinic. To assess for generalization across environments, handwashing was the ADLS conducted in the caregiver’s home for all caregivers, with the exception of Emily–Ella. Emily requested that the handwashing generalization probes be completed in a community bathroom. All eight caregivers received a typed copy of the task analyses for handwashing and putting on a jacket (see Supplemental Material), which specified any mastered steps, the training step, and nontraining steps for their child. The task analyses described the mastered steps as steps their child performed independently, the training step as the step their child was learning, and the nontraining steps as the steps their child did not know.

Caregivers in the real-time feedback group had access to the ADLS materials (e.g., jacket or soap) and their child’s preferred toys during each session. Materials present in the treatment room included a video camera, table, chairs, timer, clipboard, and writing utensils. The clinic bathroom included a soap dispenser attached to the wall, disposable paper towels, and a trash can. Sessions with caregivers in the BST group included the same materials, but the caregivers had access to written instructions (see Supplemental Material) on how to teach the ADLSs during the BST sessions. Interobserver agreement and procedural integrity were later scored from the video recordings.

At the time of the study, the lead author was a Board Certified Behavior Analyst working toward a doctorate degree in applied behavior analysis. She collected primary data and conducted all sessions with the caregiver–child dyads. Secondary data collectors included a Board Certified Behavior Analyst who served as a supervisor at the applied behavior analysis clinic and a master’s student pursuing her degree in applied behavior analysis.

Development of Task Analyses

The self-care items of the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, Third Edition (ABAS-III; Harrison & Oakland, 2015), and the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Third Edition, for 24–54 months (ASQ-3; Squires, Twombly, Bricker, & Potter, 2009) were reviewed. These are two commonly used assessment and screening tools to assess a child’s adaptive skills and developmental performance and indicate adaptive skills a child should perform during specified age ranges. Two of the top three items from the ABAS-III and ASQ-3 that overlapped were selected as the ADLS to evaluate and teach with caregiver–child dyads. The common self-care items across the two assessment tools were getting dressed (i.e., putting on a shirt or jacket) and washing hands (Harrison & Oakland, 2015; Squires et al., 2009). The investigator adapted existing published task analyses for putting on a jacket and washing hands by creating a 10-step task analysis for each ADLS (Kissel, Whitman, & Reid, 1983; Sewell, Collins, Hemmeter, & Schuster, 1998).

Two Board Certified Behavior Analysts, one Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst, three speech-language pathologists, and two caregivers not participating in the study were recruited to assess the appropriateness and similarity of the task analyses. The reviewers rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) the degree to which the ADLS’ sequences of steps were correct and the degree to which the two ADLS were similar in the number of steps to complete, similar in difficulty (i.e., fine and gross motor skills required to complete the ADLS), and similar in their time to complete. The ratings and feedback provided by the professional and caregiver reviewers indicated that the two ADLS task analyses had the correct sequence of steps and were similar in the number of steps to complete. Most reviewers indicated the level of difficulty and amount of time were similar between the two ADLS; however, two reviewers indicated that putting on a jacket might be more difficult than washing hands due to the fine and gross motor skills required to perform the skill. One reviewer also indicated that handwashing might take longer than putting on a jacket once the child mastered the skill. We used the two adapted task analyses to evaluate the child participants’ baseline performance of the ADLS for participation in this study and provided the written task analyses to caregivers across all conditions.

Dependent Measures and Data Collection

Caregiver Measures

Trained experimenters collected all measures at baseline, intervention, generalization, and maintenance conditions for both treatment groups. The primary dependent variables were summarized in two ways: the percentage of ADLS teaching procedures implemented correctly and the caregiver’s accuracy in implementing each component skill for each probe or session (see Table 1). The percentage of ADLS teaching procedures implemented correctly during each probe or session was calculated by totaling the number of components performed correctly, dividing the total by the number of components with an opportunity to occur, and multiplying the result by 100. The mastery criterion for terminating caregiver training sessions (i.e., real-time feedback or BST) was caregivers meeting the mastery criterion of 90% or higher correct implementation of teaching procedures across two consecutive real-time feedback or BST sessions. Second, we calculated the caregiver’s accuracy in implementing each component skill by dividing the number of times the caregiver implemented a component skill accurately within a probe or session by the total number of opportunities for the caregiver to implement that component skill and multiplying by 100. We used these data to assess error patterns in the caregiver’s accuracy of implementing each component skill.

Table 1.

Component Skills of the Teaching Procedure for Activities of Daily Living Skills

| Dependent measures | Operational definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Obtains child’s attention and delivers instruction | The caregiver presents the correct instruction when the child has made eye contact or orients toward the caregiver for at least 1 s (the caregiver may obtain attention by stating “look,” “look at me,” or “ready” as prompts). |

| 2. Implements 2s prompt delay and most-to-least prompting on mastered step(s) | The caregiver waits 2 s (± 3 s) after giving the instruction before administering a prescribed prompt on the mastered step (provides an opportunity for the child to respond), or the caregiver delivers a prompt immediately after the child emits an error. |

| 3. Implements 2s prompt delay and most-to-least prompting on training step | The caregiver waits 2 s (± 3 s) for the child to independently perform the training step before administering a hand-over-hand prompt. The caregiver administers a prompt if the child emits an error or engages in no response. The caregiver withholds the prompt if the child performs the response independently. |

| 4. Provides behavior-specific praise on training step | The caregiver provides behavior-specific praise immediately (within 2 s) following the child’s independent response on the training step, or the caregiver withholds praise for a prompted response. |

| 5. Guides completion on nontraining steps | The caregiver implements hand-over-hand guidance through the remaining (nontraining) steps of the behavior chain in the correct sequence. |

| 6. Delivers of praise and tangible reinforcer for training step | The caregiver provides behavior-specific praise specifying the training step performed independently and delivers access to the tangible reinforcer after completion of the behavior chain, or the caregiver withholds praise and the tangible reinforcer for a prompted response on the training step. |

The caregiver baseline, maintenance, and generalization probes consisted of a single-trial probe for both groups. The purpose of conducting single-trial caregiver probes was to reduce child participants’ exposure to teaching errors when caregivers were not receiving training on implementing the ADLS teaching procedures. The real-time feedback intervention sessions included five trials with the child. The BST intervention sessions without the child consisted of single-trial probes until the caregiver conducted two consecutive trials above 90%. Then the caregivers completed the BST intervention sessions with their child, which included five trials per sessions.

The experimenters documented the correct implementation of each teaching procedure when the caregiver (a) delivered the correct instruction while having their child’s attention, (b) implemented a 2s prompt delay with most-to-least prompting for mastered steps, (c) implemented a 2s prompt delay with most-to-least prompting for training steps, (d) delivered behavior-specific praise following the child’s independent response on the training step, (e) used hand-over-hand prompting through the remainder of the behavior chain in the correct sequence, and (f) delivered the tangible or edible reinforcer with behavior-specific praise at the end of the behavior chain if the child performed the training step independently, or withheld the reinforcer for a prompted response on the training step. The experimenters documented the incorrect implementation of ADLS teaching procedures if the caregiver (a) delivered the wrong instruction or gave the instruction without having their child’s attention, (b) administered the prescribed prompt in less than or greater than 2 s for the mastered and training steps, (c) omitted the designated prompt or provided the incorrect prompt for mastered or training steps, (d) withheld delivery of praise and the reinforcer for the child’s independent response or delivered praise and the reinforcer for a prompted response on the training step, (e) delivered the reinforcer for a nontraining step, (f) omitted hand-over-hand prompting or used the incorrect prompt through the remainder of the behavior chain, or (g) prompted the chain in the wrong sequence.

The experimenters also collected efficiency measures by documenting the total minutes for each real-time feedback and BST session and trial and calculated the total number of trials conducted with the child for both groups. The experimenters calculated the total number of trials with and without the child for the BST group, as well as the total number of sessions for the real-time feedback and BST caregivers to meet the mastery criterion with their child.

Child Measures

We summarized each child’s independent performance of ADLS steps to determine which steps were mastered, training, and nontraining steps for each probe or trial across all conditions. Specifically, during baseline child probes, the experimenter documented the child’s performance for all 10 steps of handwashing and putting on a jacket, which determined the mastered steps, training step, and nontraining steps for each ADLS during caregiver baseline probes. During all probes and sessions with the caregiver (i.e., caregiver baseline probes, real-time feedback or BST sessions, maintenance probes, and generalization probes), the experimenters followed the task analysis to mark independent step completion when the child completed the training step or mastered steps of the behavior chain without prompts from the caregiver. The experimenters marked a training step or mastered step as prompted when the child required any form of gestural or physical guidance from the caregiver. The child met the mastery criterion for the training step of the ADLS behavior chain by completing the step independently across two consecutive trials at 100%. Once the child met the mastery criterion for the training step, then the next step in the behavior chain was introduced as the new training step. We calculated the child’s independent performance of mastered and training steps of the ADLS by dividing the number of mastered and training steps performed independently by the total number of mastered and training steps specified for the child and multiplying the result by 100. There were no notable changes in the child participants’ performance across baseline and caregiver training conditions (data available from the first author).

Interobserver Agreement, Procedural Fidelity, and Social Validity

Secondary observers independently watched the videos and scored the caregivers’ implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures across all conditions for an average of 44% (range 33%–50%) of caregiver sessions in the real-time feedback group and for an average of 65% (range 33%–73%) of caregiver sessions in the BST group. The primary and secondary observers’ data were scored as an agreement if both observers recorded the same response on the caregiver implementing the components of the ADLS teaching procedures during opportunities. A disagreement was recorded if the primary and secondary observers’ data documented different responses on the caregiver’s implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures. When calculating agreement for total session times during real-time feedback and BST caregiver sessions, an agreement was documented if both observers recorded the same time within a 5-s variance. The exact agreement coefficient calculation was used to obtain a percentage of agreement by totaling the number of agreements and dividing the agreements by the total agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. Mean agreement scores for caregivers in the real-time feedback group were 94% (range 85%–100%) for Allan, 96% (range 77%–100%) for Betty, 88% (range 77%–100%) for Cindy, and 99% (range 99%–100%) for Dana. The mean agreement scores for the caregivers in the BST group were 100% for Emily, 97% (range 93%–100%) for Fran, 99% for Gary (range 99%–100%), and 98% (range 93%–100%) for Helen.

Secondary observers also independently watched the videos and scored the child’s performance of the ADLS across conditions for an average of 73% (range 33%–100%) of sessions for children in the real-time feedback group and for an average of 81% (range 33%–100%) of sessions for children in the BST group. The primary and secondary observers’ data were scored as an agreement if both observers recorded the same response of the child performing each step of the ADLS during opportunities, and a disagreement was recorded if the observers documented different child responses on the ADLS. The exact agreement coefficient method was used to obtain a percentage of agreement for child responses. Mean agreement scores for children in the real-time feedback group were 93% (range 82%–100%) for Andy, 95% (range 82%–100%) for Brice, 95% (range 82%–100%) for Caleb, and 97% (range 82%–100%) for Danny. The mean agreement scores for the children in the BST group were 97% (range 91%–100%) for Ella, 99% (range 90%–100%) for Frank, 97% (range 82%–100%) for Gabe, and 100% for Henry.

A tertiary observer scored the percentage of integrity of the experimenter’s implementation of caregiver baseline, generalization, and real-time feedback procedures for an average of 44% (range 33%–50%) of sessions for each caregiver–child dyad. The tertiary observer also scored the experimenter’s implementation of procedures across conditions for the BST group for an average of 65% (range of 33%–100%) of sessions for each caregiver–child dyad. The experimenter’s procedural fidelity was calculated for caregiver baseline and generalization procedures by dividing the number of procedural integrity procedures implemented correctly by the total number of procedural integrity procedures and multiplying by 100. The experimenter’s procedural integrity for intervention sessions was calculated by dividing the total number of real-time feedback or BST training procedures conducted correctly by the total training procedures conducted with an opportunity to occur and multiplying the result by 100. The mean fidelity score for the real-time feedback group was 99% (range 96%–100%), and the mean fidelity score for the BST group was 99% (range 99%–100%).

Caregivers in both groups completed a 10-item social validity questionnaire to report their level of satisfaction with the caregiver training on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 following the 6-week maintenance probe. Ratings closer to a score of 5 on all items, except for Item 4, indicated a high level of social acceptability. A rating closer to a score of 3 on Item 4 indicated that the amount of time spent during caregiver training was the right amount of time, whereas a score closer to 1 indicated the training was too long and a score closer to 5 indicated the training was too short.

Experimental Design and General Procedures

We used two concurrent multiple-baseline designs across caregiver–child dyads for the real-time feedback and BST groups to evaluate the effects of real-time feedback or BST on caregivers’ acquisition and implementation of ADLS teaching procedures. We randomly assigned caregiver–child dyads to tiers within the multiple-baseline design and delivered the intervention to the participants within each group concurrently. The real-time feedback and BST groups were evaluated concurrently as well. Caregivers attended one to two probes per week across all conditions, which included baseline, intervention sessions (i.e., real-time feedback or BST), and generalization probes. All caregivers received training on how to teach handwashing to their child during real-time feedback or BST sessions at the clinic. Caregivers did not receive real-time feedback or BST during baseline, generalization probes for putting on a jacket, generalization probes for handwashing in the home, or maintenance probes.

Preference Assessment

The experimenter conducted a paired-stimulus preference assessment with each child to identify the top three highest preferred toys (Fisher et al., 1992). The three preferred items were available across all trials, sessions, and conditions to allow the caregiver the opportunity to deliver the items following the child’s independent response on the ADLS training step.

ADLS Teaching Procedures

During real-time feedback and BST sessions, caregivers in both groups received training on the same ADLS teaching procedures. Caregivers received training on how to implement a forward chaining procedure for handwashing using most-to-least prompting with a 2s prompt delay on mastered and training steps. Caregivers were taught to use guided completion for the remaining steps of the behavior chain (i.e., nontraining steps) and then deliver reinforcement for independent completion of the training step. The ADLS teaching procedures included six component skills (see Table 1).

The first component of the ADLS teaching procedure included obtaining their child’s attention and delivering the instruction to complete the primary ADLS (e.g., “wash your hands”). For mastered steps and the training step, the caregiver was to use a 2s prompt delay with most-to-least prompting. If prompting was necessary after the 2s prompt delay, the most intrusive prompt was administered (i.e., physical prompt) for the training step, and once the training step was mastered, the prompt was faded to a gesture prompt. For example, if the child performed the mastered step independently, then the caregiver would move to the next step in the behavior chain. If the child required prompting for the mastered step, the caregiver would first administer a gesture prompt, and if the child still did not respond, then the caregiver would use a physical prompt.

For the training step, the caregiver was to use a 2s prompt delay. If the child performed the training step independently, then the caregiver would provide behavior-specific praise (e.g., “Good job rubbing your hands together with soap.”). The tangible reinforcer was difficult to deliver during the ADLS behavior chain; therefore, only behavior-specific praise was provided immediately following the child’s independent performance of the training step. If the child required prompting on the training step, the caregiver used a physical prompt and withheld behavior-specific praise. After completing the training step, the caregiver used manual guidance through the remaining steps (i.e., nontraining steps) of the ADLS chain. Following completion of the behavior chain, and if the child performed the training step independently earlier in the chain, the caregiver would again provide behavior-specific praise and deliver access to the tangible reinforcer. The caregiver withheld the behavior-specific praise and access to the tangible reinforcer after completing the chain if the child required prompts to perform the training step.

Child Baseline Probes

A minimum of three child baseline probes were conducted to directly assess the child’s level of independence with the handwashing ADLS. The child baseline probes were single-trial probes. The probe started when the experimenter delivered the instruction to perform handwashing and ended after the child completed the ADLS independently but incorrectly, engaged in no response for 30 s, or engaged in a response that did not correspond to the task for 30 s (e.g., motor stereotypy). The experimenter did not administer prompts or deliver tangible reinforcers after the child engaged in a correct or incorrect response.

Caregiver Baseline Probes

The experimenter handed the caregiver the handwashing task analysis to review, which indicated the mastered, training, and nontraining steps specific to their child. The experimenter asked the caregiver to instruct their child to complete the primary ADLS (e.g., “Please have Andy wash his hands.”). The experimenter remained present in the room but did not provide any real-time feedback or BST components during caregiver baseline probes. The probe started when the caregiver delivered the instruction to the child and ended when the child completed the ADLS, when the caregiver assisted the child through the ADLS, or after 30 s of no response from the child and caregiver. The investigator provided noncontingent general praise statements to the caregiver at the end of trials, such as “well done.” Baseline consisted of a single-trial probe per session.

Real-Time Feedback Group

All real-time feedback sessions were conducted with the caregiver and child present. The experimenter handed the caregiver the handwashing task analysis to review and then instructed the caregiver to implement the primary ADLS (handwashing) with their child. The experimenter provided real-time feedback on the correct and incorrect implementation of ADLS teaching procedures as the caregiver conducted each step of the ADLS with their child. If the caregiver emitted an error, the experimenter provided immediate behavior-specific corrective feedback to implement the correct ADLS teaching procedure in the next trial or opportunity. The experimenter positively stated the corrective feedback if the caregiver made an error (e.g., “Next time, wait only 2 s before prompting”) and instructed the caregiver to continue through the remaining steps of the ADLS. If the caregiver corrected an error from a previous trial at the next opportunity, the experimenter provided behavior-specific verbal praise for the corrected response. The experimenter delivered noncontingent general praise statements at the end of each trial. The experimenter implemented real-time feedback until the caregiver met the mastery criterion.

BST Group

Caregivers first received BST on teaching an ADLS without their child present. The experimenter reviewed the written instructions on the implementation of ADLS teaching procedures. The experimenter handed the caregiver the handwashing task analysis and had the caregiver review which steps were mastered, training, and nontraining specific to their child. Next, the experimenter modeled the ADLS teaching procedures two times with the caregiver and then gave the caregiver the opportunity to rehearse with the experimenter. During the caregiver’s rehearsal trial, the experimenter instructed the caregiver to implement the ADLS teaching procedure for handwashing with the experimenter as the confederate child. As the caregiver implemented the ADLS teaching procedure for handwashing, the experimenter also provided real-time feedback on the correct and incorrect use of ADLS teaching procedures as the caregiver conducted each step of the ADLS with the experimenter. The experimenter varied simulated child responses for mastered and training steps across trials. The training cycle of two models and rehearsal with real-time feedback repeated until the caregiver performed the ADLS teaching procedures at 90% correct across two consecutive trials.

Once the caregiver achieved the mastery criterion with the experimenter, the caregiver implemented the ADLS teaching procedures with their child. During BST sessions with the child, the experimenter reviewed the ADLS written instructions at the start of the session with the caregiver. The caregiver was given the handwashing task analysis and instructed to complete the ADLS with their child. The experimenter provided real-time feedback while the caregiver implemented the ADLS teaching procedures with their child. If the caregiver implemented the ADLS teaching procedures below 90% correct during the trial, the experimenter modeled with the caregiver one time and then the caregiver rehearsed with the experimenter while receiving real-time feedback. The experimenter simulated the child’s responses during the rehearsal trial to provide an opportunity for the caregiver to rehearse the correct implementation of the component skills in which they previously erred. During modeling and rehearsal between the caregiver and experimenter, the child participants either received access to the tangible reinforcer if they performed the training step for handwashing independently or received access to a less preferred item for prompted responses on the training step until the start of the next trial. After the modeling and rehearsal with real-time feedback, the caregiver would then start the next trial of the session with their child. The caregiver received the sequence of real-time feedback during the trial with their child, a model by the experimenter, and then rehearsal with real-time feedback with the experimenter until the caregiver met the mastery criterion for BST sessions with their child.

Maintenance

The experimenter conducted 1-, 3-, and 6-week maintenance probes to assess for the continuance of the caregiver’s correct and accurate implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures for both treatment groups and evaluated the child’s progress with independently performing the steps of the primary ADLS (i.e., handwashing in the clinic). The maintenance probes were conducted identically to the caregiver baseline probes.

Generalization Probes

The experimenter implemented the same procedures used in the caregiver baseline probes to conduct generalization probes for both groups across baseline, intervention, and maintenance phases. The experimenter conducted generalization probes in the clinic to assess for the caregiver’s generalization of ADLS teaching procedures to a novel ADLS (putting on a jacket). The experimenter also conducted generalization probes in the home (in the community for Emily–Ella) with the primary ADLS (handwashing) to assess for the caregiver’s generalization of ADLS teaching procedures across environments.

Results

Real-Time Feedback Group

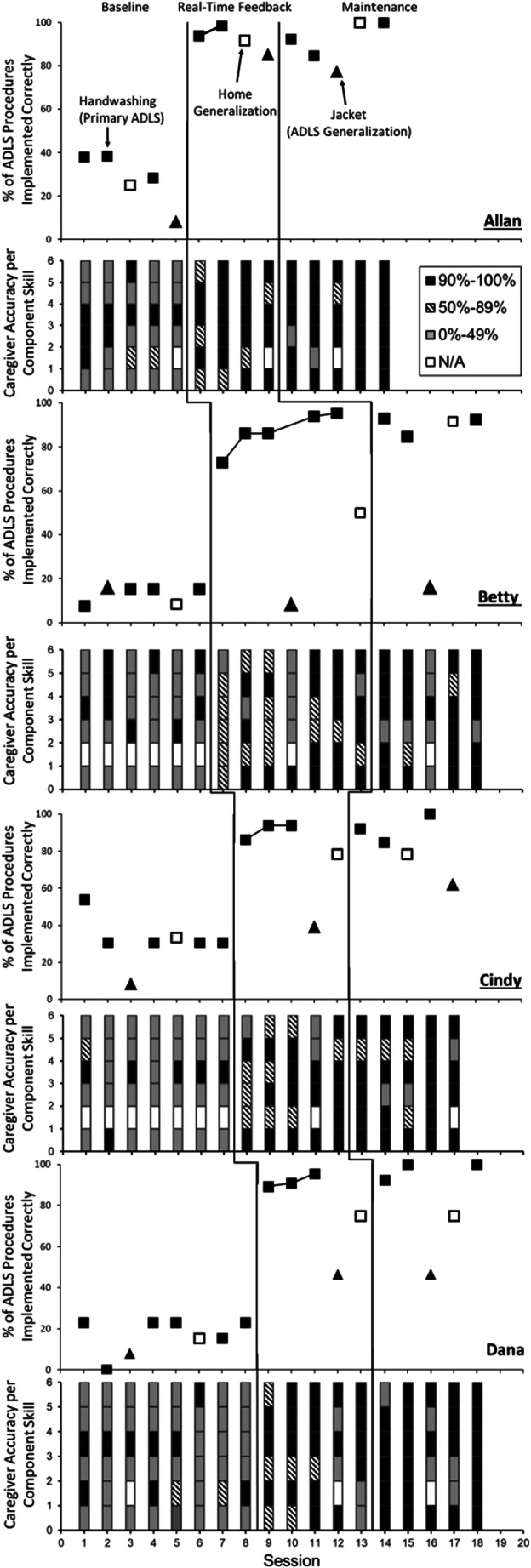

Figure 1 displays the results of the four caregivers in the real-time feedback group. The top panel for each caregiver shows the percentage of ADLS teaching procedures implemented correctly during caregiver baseline probes, real-time feedback sessions, maintenance probes, and generalization probes. The second panel for each caregiver displays each caregiver’s accuracy with implementing each ADLS component skill across all probes and sessions (see Table 1 for the list of caregiver component skills). The black boxes indicate the component skill the caregiver implemented with accuracy between 90% and 100% of opportunities for each session, and the striped boxes indicate the component skill the caregiver implemented with accuracy between 50% and 89%. The gray-shaded boxes indicate the caregiver’s accuracy between 0% and 49% for the component skill, and the white boxes indicate the component skill the caregiver did not have the opportunity to implement during the session.

Fig. 1.

The Percentage of ADLS Teaching Procedures Implemented Correctly and the Accuracy of Component Skills Implemented Across Caregivers in the Real-Time Feedback Group. Note. Panels 1, 3, 5, and 7 show the percentage of activities of daily living skill (ADLS) teaching procedures implemented correctly by each caregiver in the real-time feedback group. The closed squares represent the target ADLS (handwashing) taught in the clinic, the triangles represent generalization probes of the novel ADLS (putting on a jacket), and the open squares represent generalization probes of handwashing in the home. Panels 2, 4, 6, and 8 show the accuracy of component skills implemented across caregivers.

During caregiver baseline probes, all real-time feedback caregivers implemented ADLS teaching procedures with low treatment integrity across handwashing at the clinic, handwashing in the home, and putting on a jacket at the clinic. All four caregivers implemented Component Skill 1 with a low percentage of accuracy and overall performed Component Skills 5 and 6 with a low percentage of accuracy across baseline probes. Dana and Allan inconsistently implemented Component Skill 2 with high accuracy, Betty and Allan were variable in their accuracy with implementing Component Skill 3, and Dana and Cindy consistently performed Component Skill 3 with low accuracy. Only Allan consistently implemented Component Skill 4 at the mastery-criterion level during baseline.

After caregivers received real-time feedback, all four caregivers in the real-time feedback group immediately increased the percentage of correct implementation of ADLS teaching procedures with handwashing in the clinic (i.e., the primary ADLS). Allan met the mastery criterion within two real-time feedback sessions (M = 96%, range 94%-98%) within a total time of 14.4 min (M = 7.2, range 5.1-9.3) and maintained correct implementation of ADLS procedures above 90% at 1- and 6-week maintenance probes. Allan consistently implemented Component Skills 1, 4, 5, and 6 with an accuracy above 90% for handwashing and performed all component skills with 100% accuracy during the 6-week maintenance probe. Allan generalized the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing in the home during the real-time feedback and maintenance conditions at mastery-criterion levels and generalized the ADLS teaching procedures to the novel ADLS (i.e., putting on a jacket), but below the mastery criterion.

Betty met the mastery criterion in five real-time feedback sessions (M = 87%, range 73%-95%) within a total time of 44.1 min (M = 8.8, range 5.4-12.9) and continued to implement the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing at mastery-criterion levels at 1- and 6-week maintenance probes. Betty consistently performed Component Skills 1, 4, 5, and 6 for handwashing in the clinic with 90% accuracy during the maintenance condition and continued to make errors when implementing Component Skill 3. Betty generalized the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing in the home above 90% correct during the maintenance condition but did not generalize the ADLS teaching procedures to the novel ADLS.

Cindy met the mastery criterion within three real-time feedback sessions (M = 91%, range 86%-94%) in a total time of 23.1 min (M = 7.7, range 5.6-11) and continued to implement ADLS teaching procedures above 90% correct for the 1- and 6-week maintenance probes. During the maintenance condition, Cindy implemented Component Skills 1, 2, 4, and 6 with 100% accuracy. Cindy generalized Component Skills 1, 4, and 6 of the ADLS teaching procedures to handwashing in the home and the novel ADLS, but remained below the mastery-criterion level for the percentage of correct implementation.

During the real-time feedback sessions, Dana met the mastery criterion within three sessions (M = 92%, range 89%-95%) within a total time of 16.1 min (M = 5.4, range 5-6) and maintained correct implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures across 1-, 3-, and 6-week maintenance probes. In the maintenance condition, Dana implemented Component Skills 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 with 100% accuracy for handwashing in the clinic. Dana also generalized Component Skills 1, 4, and 6 of the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing in the home and the novel ADLS, but the percentage of correct implementation remained below the mastery-criterion level.

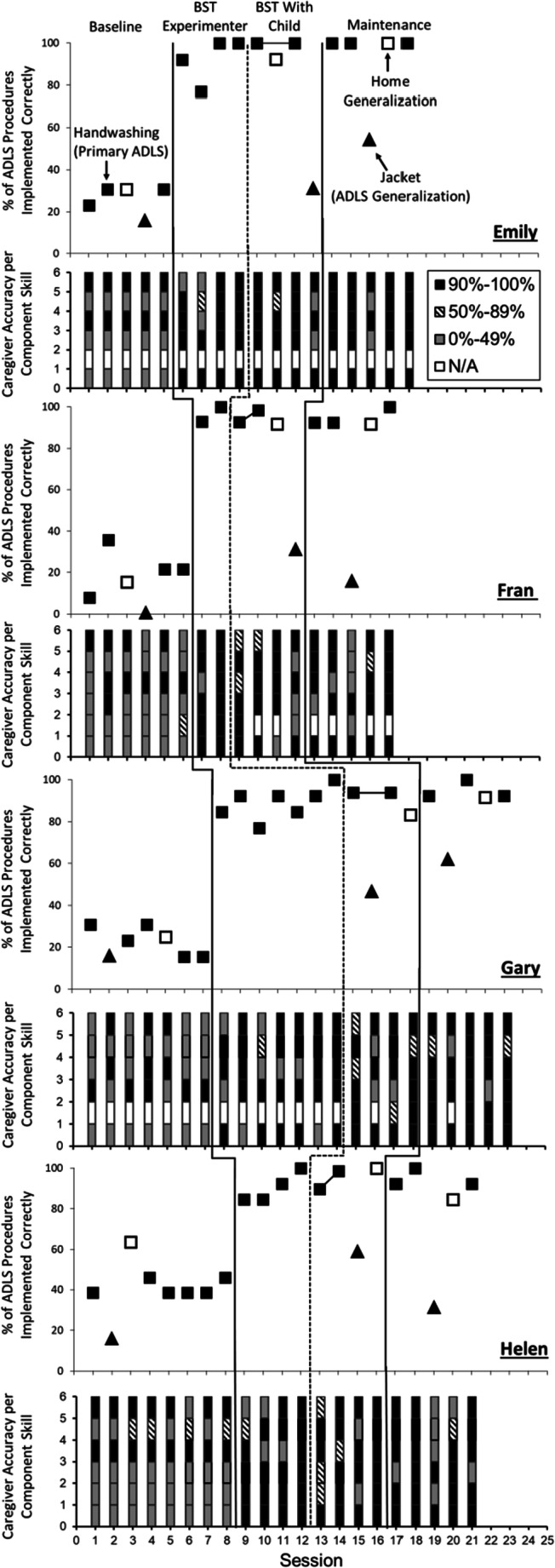

BST Group

Figure 2 depicts the results of the four caregivers in the BST group. All four caregivers implemented the ADLS procedures with low integrity during baseline probes with their child. Across caregiver baseline and generalization probes, all four caregivers implemented Component Skills 1 and 5 with a low percentage of accuracy, and Fran and Helen performed Component Skill 2 with low accuracy. Emily and Helen implemented Component Skill 3 with a low percentage of accuracy, whereas Fran’s and Gary’s responding with Component Skill 3 was variable. Overall Emily, Fran, and Helen performed Component Skill 4 with high accuracy during baseline, and Emily was the only caregiver participant who consistently implemented Component Skill 6 with 100% accuracy.

Fig. 2.

The Percentage of ADLS Teaching Procedures Implemented Correctly and the Accuracy of Component Skills Implemented Across Caregivers in the BST Group. Note. Panels 1, 3, 5, and 7 show the percentage of activities of daily living skill (ADLS) teaching procedures implemented correctly by each caregiver in the behavioral skills training (BST) group. The closed squares represent the target ADLS (handwashing) taught in the clinic, the triangles represent generalization probes of the novel ADLS (putting on a jacket), and the open squares represent generalization probes of handwashing in the home. Panels 2, 4, 6, and 8 show the accuracy of component skills implemented across caregivers.

After caregivers received BST with just the experimenter, all four caregivers in the BST group immediately increased in their percentage of correct implementation of ADLS teaching procedures with handwashing. The caregivers continued to perform the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing in the BST sessions with their child correctly at mastery-criterion levels. Emily met the mastery criterion within four BST trials with the experimenter (M = 93%, range 77%-100%) and within two BST sessions with her child (M = 100%) in a total time of 38.4 min (M = 9.6, range 4.6-21.1). Emily maintained correct and accurate implementation of the ADLS procedures and Component Skills 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 at 100% during the 1-, 3-, and 6- week maintenance probes. Emily generalized the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing to the community setting above 90% correct during BST with her child and the maintenance phase, but only generalized implementation of Component Skills 1, 4, and 6 for putting on a jacket.

The third panel of Figure 2 depicts Fran’s immediate increase in correct implementation of ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing within only two trials of BST with the experimenter (M = 96%, range 93%-100%) and two BST sessions with her child (M = 95%, range 93%-98%) within a total time of 27.4 min (M = 9.1, range 5-14.2). Fran continued to implement ADLS teaching procedures above 90% at 1-, 3-, and 6-week maintenance probes and implemented Component Skills 1, 5, and 6 with 100% accuracy for handwashing in the clinic during the maintenance condition. Fran also generalized implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures above 90% correct to the home setting during the BST and maintenance conditions but did not generalize the teaching procedures to putting on a jacket.

The fifth panel shows Gary’s increase in correct implementation of ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing within seven trials of BST with the experimenter (M = 89%, range 77%-100%) and correct implementation in only two sessions of BST with his child (M = 94%) in a total time of 35.8 min (M = 9.0, range 5.1-19.8). Gary continued to implement ADLS teaching procedures above 90% correct at 1-, 3-, and 6-week maintenance probes, and Gary implemented Component Skills 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 at 100% accuracy for handwashing in the clinic during the maintenance phase. Gary generalized ADLS teaching procedures to handwashing in the home, performed at the mastery-criterion level in the maintenance condition, and only generalized Component Skills 1, 4, and 6 to putting on a jacket during BST and maintenance conditions.

Helen reached mastery in four trials of BST with the experimenter (M = 90%, range 85%-100%) and within two sessions of BST with her child (M = 94%, range 90%-99%) in a total time of 40.9 min (M = 13.6, range 8.4-20.7). Helen continued to implement the ADLS teaching procedures above 90% correct at the 1-, 3-, and 6-week maintenance probes and was 100% accurate with implementing Component Skills 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 for handwashing in the clinic during the maintenance condition. Helen generalized ADLS teaching procedures to handwashing in the home during BST at 100% correct. For putting on a jacket, Helen only implemented Component Skills 1 and 3 consistently and implemented the procedures below the mastery criterion.

Efficiency Evaluation

The efficiency evaluation of real-time feedback and BST is shown in Table 2. Caregivers in both groups were exposed to the same baseline, maintenance, and generalization conditions, and none of the caregivers received training (i.e., real-time feedback or BST) during these probes. Therefore, the data depicted on the table only include sessions, trials, and total duration to meet the mastery criterion when caregivers received real-time feedback or BST. Caregivers in the real-time feedback group received real-time feedback while implementing ADLS teaching procedures with their child. Therefore, the data depicted for the real-time feedback group include the number of sessions to mastery with their child present (M = 3.2 sessions, range 2-5), the total trials to mastery with their child (M = 16 trials, range 10-25), and the total duration for all real-time feedback sessions (M = 24.4 min, range 14.4-44.1).

Table 2.

Efficiency Evaluation Results of Real-Time Feedback (RTF) and Behavioral Skills Training (BST)

| Participant | Group | Caregiver training to mastery | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sessions | Total trials | Trials | Duration (minutes) | ||

| Allan | RTF | 2 | — | 10 | 14.4 |

| Betty | RTF | 5 | — | 25 | 44.1 |

| Cindy | RTF | 3 | — | 15 | 23.1 |

| Dana | RTF | 3 | — | 15 | 16.1 |

| Emily | BST | 2 | 14 | 10 | 38.4 |

| Fran | BST | 2 | 12 | 10 | 27.4 |

| Gary | BST | 2 | 17 | 10 | 35.8 |

| Helen | BST | 2 | 14 | 10 | 40.9 |

Note. Total trials include BST trials with just the experimenter and with the child. Dashes denote that the RTF did not include trials with just the experimenter.

Caregivers in the BST group first received BST with the experimenter until they met the mastery criterion and then received BST with their child. The total sessions to mastery for the BST group includes only BST sessions with their child, and all four caregivers in the BST group reached the mastery criterion within two sessions and 10 trials. The total trials to mastery for the BST group include the BST trials conducted with the experimenter and the trials conducted during BST sessions with their child (M = 14 trials, range 12-17). The total duration of BST sessions includes all BST trials and sessions (i.e., with the experimenter and child; M = 35.6 min, range 27.4-40.9). The caregivers in the BST group required fewer sessions and trials to mastery with the child present; however, caregivers in the BST group required more minutes to meet the mastery criterion than the real-time feedback group.

The results of reported satisfaction with training from the caregivers in the real-time feedback group are displayed in Table 3. Overall, caregivers in the real-time feedback group highly rated their training experience and reported satisfaction with real-time feedback as indicated by ratings of 3 to 5. Caregivers in the real-time feedback group also rated the amount of time in training as about right (i.e., Item 4; rating of 3). Two of the four caregivers in the real-time feedback group reported a preference for including video modeling (i.e., Item 3).

Table 3.

Caregiver Satisfaction Ratings and Responses to Real-Time Feedback

| Question | Allan | Betty | Cindy | Dana |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overall, were you satisfied with the caregiver training process in teaching your child self-care skills? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 2. Were you satisfied with the process in which feedback was provided during the training? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 3. What other modes of training would you have preferred? | Video model | None | None | Video model |

| 4. The amount of time spent in caregiver training was __. | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 5. Rate your overall level of comfort during the caregiver training process. | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 6. Rate your willingness to participate in training on other procedures using the same mode of caregiver training (i.e., feedback during sessions). | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 7. Please rate the level of confidence in your ability to teach your child self-care skills after participating in caregiver training. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 8. How willing are you to carry out the self-care teaching procedures with your child at home? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 9. How likely is this procedure to make meaningful improvements on your child’s independence in completing self-care skills? | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 10. How meaningful were the self-care skills you taught to your child? | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Note. Caregiver responses on a 5-point Likert scale with ratings from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate greater agreement with the question or statement. On Item 4, a rating of 1 = too lengthy, 3 = about right, and 5 = too short.

The results of reported satisfaction with training for the caregivers in the BST group are summarized in Table 4. Caregivers in the BST group overall rated their training experience and satisfaction as high as indicated by ratings of 3 to 5. One caregiver in the BST group reported a preference for including video modeling (i.e., Item 3), and all four caregivers gave ratings of 5 for in-the-moment feedback (i.e., real-time feedback; Item 2d). Caregivers in the BST group rated the amount of time in training as about right, as indicated by their ratings of 3 to 4 (i.e., Question 4). Altogether, caregivers for both groups reported a willingness to implement the ADLS teaching procedures at home with their child and that implementing the ADLS teaching procedures will likely make meaningful improvements to their child’s independence in performing ADLSs.

Table 4.

Caregiver Satisfaction Ratings and Responses to Behavioral Skills Training

| Question | Fran | Emily | Gary | Helen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overall, were you satisfied with the caregiver training process in teaching your child self-care skills? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 2. Please rate how much you liked each mode of training: | ||||

| 2a. Review of written instructions. | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 2b. Modeling of the self-care skills protocol with the therapist. | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 2c. Role-play of the self-care skills protocol with the therapist. | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 2d. Verbal feedback on correct/incorrect teaching of self-care skills. | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 3. What other modes of training would you have preferred? | None | None | None | Video model |

| 4. The amount of time spent in caregiver training was __. | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 5. Rate your overall level of comfort during the caregiver training process. | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 6. Rate your willingness to participate in training on other procedures using the same mode of caregiver training. | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 7. Please rate the level of confidence in your ability to teach your child self-care skills after participating in caregiver training. | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 8. How willing are you to carry out the self-care teaching procedures with your child at home? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 9. How likely is this procedure to make meaningful improvements on your child’s independence in completing self-care skills? | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 10. How meaningful were the self-care skills you taught to your child? | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

Note. Caregiver responses on a 5-point Likert scale with ratings from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate greater agreement with the question or statement. On Item 4, a rating of 1 = too lengthy, 3 = about right, and 5 = too short.

Discussion

The current study trained eight caregivers using real-time feedback or BST to implement ADLS teaching procedures with their young children with ASD. All caregivers correctly and accurately implemented components of the ADLS teaching procedures with their child after receiving real-time feedback or BST and maintained correct implementation of the procedures. The real-time feedback results from the current study are consistent with the findings from the Ausenhus and Higgins (2019) study, which demonstrated that real-time feedback was a quick and effective method to train behavioral procedures to mastery-criterion levels and maintain the effects at follow-up. Caregivers in the real-time feedback group acquired mastery levels of ADLS teaching procedure implementation within few sessions and minutes.

The results of the BST group in the present study extend previous research by demonstrating the efficacy of BST to train caregivers to implement behavioral interventions (Dogan et al., 2017; Lafasakis & Sturmey, 2007; Seiverling et al., 2012). The total training time for caregivers in the BST group was relatively greater than the overall time for the real-time feedback group; however, the total time for each caregiver in the BST group to meet mastery was less than reports from previous BST studies (Dogan et al., 2017; Hassan et al., 2018). In previous studies, experimenters provided feedback at the end of the trial or session or on a weekly basis (Anderson & McMillan, 2001; Dogan et al., 2017; Lafasakis & Sturmey, 2007). The current study included real-time feedback within the BST package; thus, the experimenter’s immediate feedback for errors or corrections made by the caregiver on each ADLS teaching component potentially prevented the caregiver from making teaching errors in subsequent trials.

Although numerous studies have applied BST to train caregivers, the current study differs in that we used BST to train caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures with their young children with ASD and conducted an efficiency analysis by isolating the feedback component of the BST package. The present study also contributes to research on caregiver training by demonstrating that real-time feedback is an effective and potentially alternative approach to train caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures. The only difference in caregiver training between the two groups was the absence of the additional BST components (i.e., written instructions, modeling, and rehearsal). The overall outcomes demonstrate that real-time feedback alone is an effective caregiver training method; however, the degree to which real-time feedback is more effective than BST cannot be determined from the present results because each caregiver only received one of the two trainings. The real-time feedback group overall required fewer minutes to mastery, although the BST group required fewer sessions to mastery with their child relative to caregivers in the real-time feedback group.

There are aspects of the results from the current study that warrant further discussion. Caregivers in the BST group completed training trials with the experimenter before implementing the ADLS teaching procedures with their child to emulate typical BST packages in which training is first completed with the experimenter, after which caregivers complete posttraining sessions with their child. For the real-time feedback procedures, we chose to conduct training sessions only with the caregiver and child to evaluate the efficiency in training caregivers without the additional training components used in BST. The additional rehearsal opportunities for caregivers in the BST group may account for the fewer sessions and trials to meet the mastery criterion relative to the real-time feedback group, which suggests potential advantages to conducting role-play trials without the child. The experimenter controlled the caregiver’s exposure to correct and incorrect simulated child responses during BST role-play trials with the experimenter, which allowed caregivers to demonstrate mastery across varying responses before implementing the procedures with their child. Additionally, the child participants in the BST group were exposed to fewer caregiver integrity errors than child participants in the real-time feedback group.

Although providing real-time feedback with the caregiver and child may reduce the amount of time spent in caregiver training, there are potential clinical implications for providing caregiver training with and without the child present. Clinicians should use their best clinical judgment to determine when training with the caregiver in the absence of the child is most appropriate. For example, when caregivers receive caregiver training for challenging behavior, clinicians may have the caregiver first practice with the clinician before requiring the caregiver to implement the procedures with their child to avoid and prevent injury. Another situation in which a clinician may initially have a caregiver receive training without their child present is with skill acquisition procedures, because the implementation of teaching procedures with low integrity can negatively impact a child’s acquisition and maintenance of skills (Carroll, Kodak, & Adolf, 2016; Donnelly & Karsten, 2017). This was avoided by having the caregiver rehearse with the clinician until the caregiver could perform the procedures with high integrity before implementing the procedures with their child. This limited the number of treatment integrity errors the child was exposed to during training with the caregiver.

There are some limitations of the current study that should be addressed. First, we were unable to conduct a direct comparison of efficiency for real-time feedback and BST. Because caregivers only received one of the two training methods, we can only compare the efficiency of the caregiver training within each group and are unable to conclude definitively on whether real-time feedback is more efficient than BST. Future research should conduct a direct comparison of the two training methods and assess potential differences in the training procedures’ effects on acquisition, generalization, and long-term maintenance. The various types of ADLS children with ASD need to perform independently change as they progress through adolescence and adulthood. Therefore, identifying caregiver training procedures that teach caregivers to generalize and continue implementing effective ADLS teaching strategies can enable caregivers to adapt to these developmental changes to assist and teach their child to complete new ADLS (Carothers & Taylor, 2004).

Second, caregivers either continued to make errors or marginally improved their implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures with the novel ADLS (i.e., putting on a jacket) after training. The current study only trained caregivers the ADLS teaching procedures with one ADLS, whereas a recommended strategy to train caregivers to successfully implement the same teaching procedures across skills is conducting multiple-exemplar training (D. L. Lerman, LeBlanc, & Valentino, 2015). Thus, training caregivers the ADLS teaching procedures across two to three different ADLSs may have allowed for an evaluation of response generalization to the novel ADLS in the current study. A third limitation is that we used the percentage of correct implementation of ADLS teaching procedures as the mastery criterion for caregivers. The percentage of accuracy in implementing each ADLS component would potentially serve as a more stringent mastery criterion, as it would require caregivers to demonstrate mastery of each component skill. Although caregivers in the present study maintained the ADLS teaching procedures for handwashing, additional research is needed to determine how a more conservative mastery criterion affects long-term maintenance and generalization.

Finally, we observed minimal to no changes in child participants’ performance with the ADLS. Although the primary purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and efficiency of our caregiver training procedures on the caregivers’ implementation of the ADLS teaching procedures, we did collect data on each child’s performance with handwashing and putting on a jacket across all conditions. Child participants were observed to either gradually acquire a few steps of the primary ADLS (i.e., handwashing) or did not acquire any new steps. These findings are similar to the results of Donnelly and Karsten (2017), which illustrated the gradual acquisition of behavior chain steps even with high-integrity teaching and several training opportunities. Thus, young children with ASD may require numerous high-integrity teaching trials to acquire mastery of an entire behavior chain. In this study, the child participants only had sessions with their caregivers one to two times per week during real-time feedback and BST sessions; therefore, additional teaching sessions could have improved the children’s performance in completing ADLSs. Future research should replicate the current study and evaluate the acquisition of ADLS with young children with ASD taught by their caregivers in order to identify an appropriate mastery criterion for caregiver training sessions and observe changes in child performance during caregiver maintenance sessions. Child participants may continue to gradually acquire steps of the ADLS if caregivers continue to implement and practice the ADLS using the ADLS teaching procedures outside of the caregiver training context.

There are several areas of future research to investigate based on the outcomes of the present study. Ausenhus and Higgins (2019) demonstrated the effectiveness of training staff to conduct preference assessments via telehealth using real-time feedback. The present study conducted sessions in a clinic, and the experimenter traveled to the caregiver’s home for generalization probes. Future studies should evaluate whether real-time feedback provided through telehealth is an efficacious caregiver training approach. Providing caregiver training through telehealth would reduce the time and cost spent traveling for caregivers, especially for those families who live in remote areas. Real-time feedback provided through telehealth would also provide a feasible option for families and practitioners to assess for generalization of their child’s ADLS across environments, troubleshoot generalization barriers, and provide booster training sessions to caregivers to maintain high levels of treatment integrity.

Because both real-time feedback and BST were effective to train caregivers to implement ADLS teaching procedures, researchers may consider evaluating caregiver preferences for caregiver training packages or components. Using a concurrent-chains assessment, the preference results may inform researchers and practitioners on whether there is unanimity in caregivers’ preferences for specific BST components and if caregivers’ preferences result in the most efficient modality of acquiring and implementing behavioral procedures with high integrity. Finally, due to the limited research published on training caregivers to implement ADLS with their child, researchers should continue to evaluate ADLS teaching procedures across different ADLS to examine the effects on the child’s long-term performance when trained by their caregivers. Furthermore, studies should replicate the use of real-time feedback to train caregivers to implement broader skills, such as other ADLS, adaptive behaviors, social skills, and functional communication.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 35.9 kb)

Funding

This study was partially funded by fellowship funds from the Buffett Early Childhood Institute Graduate Scholars Program at the University of Nebraska.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This research was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree of philosophy for Elizabeth J. Preas at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Research Highlights

• Real-time feedback may be an efficient alternative approach to train caregivers procedures to teach activities of daily living skills (ADLS).

• Providing behavior-specific feedback in the moment on each component of a teaching procedure can improve a caregiver’s performance of implementing ADLS immediately.

• As with previous research on behavioral skills training, this training is an effective approach to train caregivers ADLS teaching procedures and may allow caregivers more practice opportunities prior to implementing the procedures with their child.

• Caregivers may require training across multiple ADLS to demonstrate generalization of the ADLS teaching procedures to novel ADLS.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, McMillan K. Parental use of escape extinction and differential reinforcement to treat food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34(4):511–515. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausenhus JA, Higgins WJ. An evaluation of real-time feedback delivered via telehealth: Training staff to conduct preference assessments. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):643–648. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00326-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft SL, Weiss JS, Libby ME, Ahearn WH. A comparison of procedural variations in teaching behavior chains: Manual guidance, trainer completion, and no completion of untrained steps. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44(3):559–569. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carothers DE, Taylor RL. How teachers and parents can work together to teach daily living skills to children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2004;19(2):102–104. doi: 10.1177/10883576040190020501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RA, Kodak T, Adolf KJ. Effect of delayed reinforcement on skill acquisition during discrete-trial instruction: Implications for treatment-integrity errors in academic settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(1):176–181. doi: 10.1002/jaba.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett JL, Fleming RK, Doepke KJ, Stevens JS. Parent training: acquisition and generalization of discrete trials teaching skills with parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2007;28(1):23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demchak M. Response prompting and fading methods: A review. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1990;94(6):603–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan RK, King ML, Fischetti AT, Lake CM, Mathews TL, Warzak WJ. Parent-implemented behavioral skills training of social skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50(4):805–818. doi: 10.1002/jaba.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly MG, Karsten AM. Effects of programmed teaching errors on acquisition and durability of self-care skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50(3):511–528. doi: 10.1002/jaba.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AW, Bishop SL. Understanding the gap between cognitive abilities and daily living skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders with average intelligence. Autism. 2015;19(1):64–72. doi: 10.1177/1362361313510068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MA, Case L, Garrick M, MacIntyre-Grande W, Carnwell J, Sparks B. Teaching child-care skills to mothers with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(1):205–215. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(2):491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz ML. The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(4):343–349. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow LL, Carr JE, Gunby KV, Charania SM, Gonsalves L, Ktaech IA, Kisamore AN. Deviations from prescribed prompting procedures: Implications for treatment integrity. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2009;18(2):142–156. doi: 10.1007/s10864-009-9085-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber DJ, Poulson CL. Graduated guidance delivered by parents to teach yoga to children with developmental delays. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(1):193–198. doi: 10.13023/ETD.2018.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PL, Oakland T. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System. 3. Western Psychological Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M, Simpson A, Danaher K, Haesen J, Makela T, Thomson K. An evaluation of behavioral skills training for teaching caregivers how to support social skill development in their child with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(6):1957–1970. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3455-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RD, Keilitz I. Training mentally retarded adolescents to brush their teeth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1975;8(3):301–309. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1975.8-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissel RC, Whitman TL, Reid DH. An institutional staff training and self-management program for developing multiple self-care skills in severely profoundly retarded individuals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1983;16(4):395–415. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1983.16-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafasakis M, Sturmey P. Training parent implementation of discrete-trial teaching: Effects on generalization of parent teaching and child correct responding. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40(4):685–689. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.685-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DL, LeBlanc LA, Valentino AL. Evidence-based application of staff and caregiver training procedures. In: Roane HS, Ringdahl JE, Falcomata TS, editors. Clinical and organizational applications of applied behavior analysis. Elsevier; 2015. pp. 321–351. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC, Swiezy N, Perkins-Parks S, Roane HS. Skill acquisition in parents of children with developmental disabilities: interaction between skill type and instructional format. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21(3):183–196. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(00)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby ME, Weiss JS, Bancroft S, Ahearn WH. A comparison of most-to-least and least-to-most prompting on the acquisition of solitary play skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1(1):37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03391719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDuff GS, Krantz PJ, McClannahan LE. Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism. In: Maurice C, Green G, Foxx RM, editors. Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism. Pro-Ed; 2001. pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Hattier MA, Belva B. Treating adaptive living skills of persons with autism using applied behavior analysis: A review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012;6(1):271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Taras ME, Sevin JA, Love SR, Fridley D. Teaching self-help skills to autistic and mentally retarded children. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1990;11(4):361–378. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(90)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles NI, Wilder DA. The effects of behavioral skills training on caregiver implementation of guided compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42(2):405–410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]