Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between the generosity of Medicaid home‐ and community‐based services (HCBS) and the likelihood of community discharge among Medicare‐Medicaid dually enrolled older adults who were newly admitted to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs).

Data Sources

National datasets, including Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF), Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR), Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX), minimum data set (MDS), and publicly available data at the SNF or county level, were linked.

Study Design

We measured Medicaid HCBS generosity by its breadth and intensity and described their variation at the county level. A set of linear probability models with SNF fixed effects were estimated to characterize the association between HCBS generosity and likelihood of community discharge from SNFs. We further stratified the analyses by the type of index hospitalizations (medical vs surgical events), age group, and the Medicaid cost‐sharing policy for SNF services.

Data Extraction Methods

The final analytical sample included 224 229 community‐dwelling dually enrolled older duals who were newly admitted to SNFs after an acute inpatient event between October 1, 2010, and September 30, 2013.

Principal Findings

We observed substantial cross‐sectional and over‐time variations in HCBS breadth and intensity. Regression results indicate that on average, a 10 percentage‐point increase in HCBS breadth was associated with a 0.7 percentage‐point increase (P < 0.01) in the likelihood of community discharge. Such relationship could be modified by individual factors and state policies: significant effects of HCBS breadth were detected among medical patients (0.7 percentage‐point, P < 0.05), individuals aged older than 85 (1.5 percentage‐point, P < 0.01), and states with and without lesser‐of policies (0.5 and 2.3 percentage‐point, respectively, P < 0.05). No significant relationship between HCBS intensity and community discharge was detected.

Conclusions

Higher Medicaid HCBS breadth but not intensity was associated with a greater likelihood of community discharge, and such relationship could be modified by individual factors and state policies.

Keywords: care transitions, home‐ and community‐based services, Medicaid, postacute care

What is known on this topic?

Medicaid has been shifting its long‐term services and support toward home‐ and community‐based services (HCBS) in the last few decades.

Medicare‐Medicaid dually enrolled older adults who entered skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) for postacute care were more likely to become nursing home long‐stay residents than Medicare‐only beneficiaries.

In states with greater HCBS spending, nursing facilities had higher rates of successful community discharge, and SNF residents were less likely to become long‐stay residents.

What this study adds?

Our study differentiated the breadth and intensity of Medicaid HCBS and found greater HCBS breadth being associated with greater likelihood of returning to community from SNFs.

The association between HCBS breadth and community discharge was stronger among duals who were the oldest old, receiving medical treatment for the index hospitalization, or residing in states with more generous Medicaid policies for paying the cost‐sharing for Medicare SNF services.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nearly 2 million older adults receive postacute care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) each year, 1 , 2 and a vast majority hope to return home. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 One key barrier to returning home that older SNF patients face is the lack of adequate support in the community to meet their care needs. 7 , 8 Many older adults with functional and cognitive impairments rely on informal caregivers, usually family members or friends, for support to remain at home. But such supportive care is often stressful on caregivers and may not be sustainable, especially as care needs increase over time. Transitions from community to hospital and subsequently to SNF are associated with further deterioration of a patient's health status and increased intensity of care needs. 9 , 10 Without sufficient care supports in the community, SNF patients may fail to return to the community and become long‐stay nursing home residents.

Low‐income patients are particularly at high risk of becoming long‐stay residents, as they often have inadequate social supports and less ability to pay out‐of‐pocket to support their living in the community. 11 Specifically, SNF users who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid (referred to herein as “duals”) have poorer health status, 12 greater functional limitations, 13 and worse living conditions in the community 14 , 15 , 16 than Medicare‐only beneficiaries. With these barriers to community discharge, duals admitted to SNF are about twice as likely to become long‐stay residents as their Medicare‐only counterparts. 13 , 17

In the last three decades, Medicaid has been shifting its provision of long‐term services and supports (LTSS) toward home‐ and community‐based services (HCBS) relative to institutional care, with the goals of providing an alternative for those who prefer to remain in the community and potentially reducing the rapid growth in LTSS costs. To that end, Medicaid's investment in HCBS has been substantial: the percentage of total Medicaid LTSS expenditures going to HCBS more than tripled, from 18% in 1995 to 57% in 2016. 18 Yet states vary significantly in their Medicaid HCBS investment. For example, in 2013, states spent between 21% and 78% of their total Medicaid LTSS dollars on HCBS. 19 If expansion of Medicaid HCBS provides duals with more accessible and comprehensive community‐based services, they may be more able to remain in the community. Indeed, HCBS has been shown to reduce or delay nursing home placement among duals, especially for people with lower levels of impairment. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23

To date, there is limited and conflicting evidence as to whether Medicaid HCBS may facilitate community discharge for duals in SNFs. In a Minnesota nursing home transition study, the ratio of HCBS recipients to nursing home residents in the county was significantly related to the likelihood of community discharge among newly admitted nursing home residents, while no significant relationship was found between HCBS expenditures per recipient and community discharge. 24 Another study found that while duals who used SNF services were more likely to become long‐stay residents than Medicare‐only beneficiaries, higher Medicaid HCBS per capita spending tended to reduce that differential. 17 A recent study found that SNF‐level rate of successful community discharge was positively associated with the proportion of state Medicaid LTSS spending on HCBS. 25 However, these existing studies have several limitations. First, the measurement of HCBS generosity employed in these studies did not match the scope of the study population, for example, using Medicaid HCBS policy to predict outcome for all nursing home residents regardless of payer source. Furthermore, no study, to our knowledge, has examined the effect of time‐varying HCBS generosity on SNF‐to‐community discharge at the individual level. The existing studies mostly relied on cross‐sectional designs, and the effect of HCBS may be confounded by unobserved geographic variation.

The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between Medicaid HCBS breadth and intensity, two distinct dimensions of HCBS generosity, 26 and the likelihood of community discharge among duals newly admitted to SNFs. Taking advantage of the rapid expansion in Medicaid HCBS over time and the wide variations in the provision of HCBS across geographic regions, this study is designed to address some of the limitations in the current literature. Using multiple national data sources, we constructed HCBS breadth and intensity measures among fee‐for‐service (FFS) older duals, which is consistent with the study population, and examined the relationship between time‐varying HCBS generosity and community discharge from SNFs. We model these relationships using SNF fixed effects, which effectively model the change in community discharge as a function of the change in HCBS policies, a substantial improvement over cross‐sectional analyses that simply model the correlation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data

Several national datasets, including Medicare, Medicaid, and the minimum data set (MDS) 2.0 and 3.0 between CY2010 and 2013, were linked at the individual level. Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) Personal Summary file includes data on beneficiaries' demographic characteristics, Medicaid enrollment, Medicaid managed care enrollment and waiver enrollment, service utilization, and costs. MAX data from 2010 to 2012 are available nationally (except for KS and ME for 2010 and ID for 2011), and data from 28 states are available for 2013. 27 We did not include years later than 2013 due to the limited availability of MAX data: MAX is available only for 17 states in 2014 and not available after 2015. The MDS is a federally required comprehensive assessment tool for all residents in Medicare‐ or Medicaid‐certified SNFs. Residents are assessed at the time of admission, at least every quarter if a resident remains in the facility, whenever a change in status occurs, and at discharge. The assessments contain detailed information on individual demographics and health status, and information on the admission source, length of nursing home stay, and discharge destination. We also used Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) and Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR). MBSF data include Medicare beneficiary enrollment information, Medicare‐Medicaid dual status, and medicare advantage (MA) enrollment. MedPAR contains information about Medicare inpatient claims.

Lastly, we obtained publicly available data containing information on facility and county characteristics, including the nursing home compare (NHC) data, the LTCfocus database, 28 Area Health Resource File (AHRF), and American Community Survey (ACS) data.

2.2. Cohort

The study cohort includes community‐dwelling older duals who were FFS users of Medicare with full eligibility for Medicaid benefits and who were newly admitted to SNFs after an acute inpatient event between October 1, 2010, and September 30, 2013. Community‐dwelling older adults were defined as those who were 65 years or older at the time of SNF admission and did not receive any nursing home care in the prior 100 days. We focused on newly admitted individuals because their care needs and social supports are likely to be different from those who previously lived in a nursing home, and individuals with a recent nursing home stay have a higher probability of returning and becoming long‐stay residents. 17 Individuals who entered SNFs in a coma were excluded.

SNF postacute residents were identified based on MedPAR and MDS data. Specifically, we required an individual to be admitted to an SNF within 1 day after a Medicare‐covered acute hospital discharge. We focused on FFS Medicare beneficiaries because SNFs may have different financial incentives to admit and discharge MA beneficiaries. In addition, because the variable of interest, HCBS generosity, can be calculated only for Medicaid FFS recipients, we excluded duals with Medicaid comprehensive managed care organization coverage, managed LTSS (MLTSS) coverage, and the program of all‐inclusive care for the elderly coverage. At the state level, we also excluded 11 states (Arizona, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah) because HCBS generosity could not be accurately measured due to the preponderance or expansion of Medicaid managed care programs in these states. Finally, after excluding individuals due to missing county of residence and missing in other covariates (3.5% and 5.2% of the sample), our analytical sample included 224 229 individuals.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcome

The key outcome is community discharge from SNFs, measured as a dichotomous variable indicating whether an SNF resident is discharged to the community within 100 days of SNF postacute admission. The 100‐day cutoff was chosen because Medicare covers SNF care for up to 100 days; thus, this is also the threshold that nursing home quality measures use to distinguish short‐ and long‐stay residents. 29

2.3.2. HCBS generosity measures

As the generosity of Medicaid HCBS programs can be considered in two dimensions, the size of the populations they serve and the intensity of the services they provide to each user once access is granted, 21 , 26 , 30 we measured Medicaid HCBS generosity by its breadth and intensity. Breadth was defined as the proportion of FFS older duals who used any HCBS in a given year, which captured realized access to Medicaid HCBS. Intensity was calculated as the average monthly HCBS spending per HCBS user per enrolled month with adjustment for Area Wage Index and is intended to reflect the amount of services used by individuals conditional on receiving HCBS. This approach of constructing HCBS generosity measures has been validated through factor analysis in a previous study. 21 , 26 , 30 For both HCBS breadth and intensity, individual HCBS utilization information from MAX data was aggregated to the county level, and the utilization and spending of HCBS included both state‐plan HCBS and waiver programs. We measured HCBS generosity at the county level rather than the state because in many states, HCBS waiver enrollment is managed by the county and waiver eligibility and availability of services are county‐specific.

2.3.3. Covariates

A comprehensive set of covariates related to community discharge was included in the analyses to reduce confounding. Individual‐level covariates included sociodemographic characteristics (eg, age, gender, race, marital status), reason for Medicare entitlement, functional status (activities of daily living [ADL] 31 ), cognitive status (cognitive function scale [CFS] 32 ), characteristics of index hospitalization (eg, type of hospital stay [surgical vs medical], use of the intensive care unit [ICU], weights of diagnosis‐related group [DRG], etc.), prior hospitalization, active diagnoses (eg, hypertension, asthma, Alzheimer's disease and related dementia [ADRD], anxiety, etc.), health conditions (eg, incontinence, etc.), and SNF treatments (eg, injection, etc.). The selection of diagnoses, conditions, and treatments was based on their prevalence among SNF residents and CMS's risk adjustment for successful community discharge. 33 Individual demographics, functional status, diagnoses, and treatment measures were identified from the SNF admission assessment (or the first available assessment if no admission assessment was available) in the MDS, and the characteristics of the index hospitalization were identified from MedPAR.

SNF facility‐level covariates included number of beds, for‐profit status, chain affiliation, occupancy rate, percent of residents covered by Medicare and Medicaid, and overall quality rating from NHC. County‐level covariates included economic factors (median household income, poverty rate, and deep poverty rate), housing factors (percent of homes being occupied by owners, median house value, and median rent), and factors related to LTSS supply (NH beds per 1000 population, home health agency per 1000 population, and female labor force participation).

2.4. Statistical analysis

We first conducted a descriptive analysis of the distribution of Medicaid HCBS generosity and characteristics of the study cohort. For HCBS generosity, we examined geographic variation and change over time in HCBS breadth and intensity at state and county levels. We compared individual characteristics, such as sociodemographics and health status, between dual SNF users who were and were not discharged within 100 days, using a t test for continuous variables or a chi‐square test for dichotomous variables.

We then conducted individual‐level analyses using the repeated cross‐sectional study design. Linear probability models with SNF fixed effects and robust SEs were estimated to explore the relationship between Medicaid HCBS generosity and the likelihood of community discharge among newly admitted dually eligible SNF residents. The SNF fixed effects account for facility‐level unobserved time‐invariant factors, such as the facility's practice norms, that may affect the likelihood of community discharge and quality of care. SNF fixed effects also account for time‐invariant county or state characteristics, which may be a significant source of confounding often seen in cross‐sectional studies. In addition, we controlled for a comprehensive list of individual characteristics and health conditions as well as year dummy variables. SNF and county‐level covariates were not included in the analysis because they are largely time‐invariant and were already accounted for by the SNF fixed effects.

We also conducted several stratified analyses to explore potential variations in the relationship between HCBS generosity and SNF community discharge across different populations. We first stratified SNF residents based on their type of index hospitalization (ie, surgical or medical, identified based on DRG) because these two groups of residents could be very different regarding their health conditions, purpose for SNF care, and needs. 34 We then stratified the sample into three groups based on residents' age at SNF admission (65‐74, 75‐84, and 85 years and older) because health status and care needs as well as the potential source of community support (eg, family structure) are different for younger vs older persons. 35 Finally, we stratified states by the presence of a Medicaid payment policy that limits Medicaid's payment to Medicare cost‐sharing for SNF services, that is, the SNF lesser‐of policy. Specifically, while Medicare requires coinsurance for SNF care from 21st to 100th day and it is typically paid by Medicaid for duals, states with lesser‐of policies will pay the lesser of two amounts: (a) the full Medicare coinsurance for SNF care or (b) the difference between the Medicaid rate and the amount already paid by Medicare. 36 If the amount already paid by Medicare exceeds the Medicaid nursing home rate, the Medicare coinsurance will not be paid by Medicaid. Because this reimbursement policy is likely to affect SNFs' incentive to discharge their dually enrolled residents as early as possible, the effect of Medicaid HCBS generosity on community discharge could be different in states with and without lesser‐of policies.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to check the robustness of the main findings. First, we defined the outcome with a different time frame, that is, whether a newly admitted SNF patient was discharged to community by the 20th day after SNF admission, to test whether HCBS generosity would affect community discharge in a shorter time frame. Second, we excluded individuals who died within 100 days of SNF admission, as the motivation to discharge could be different among people approaching the end of life. Third, to test robustness of our measure definitions, we constructed two mixed HCBS generosity measures that are more commonly used in the existing literature (the proportion of LTSS spending on HCBS and per capita HCBS spending among older adults) 17 , 25 , 37 , 38 and examined the association between community discharge and each of these two mixed HCBS measures. Fourth, we excluded counties with extreme HCBS breadth or intensity (below 1% or above 99%) to reduce the impact of outliers. Lastly, we used two other model specifications including a set of hierarchical linear models and conditional fixed‐effects logit model to test the robustness of the results. The hierarchical model included state dummies and random intercept at both the county and SNF level, and we accounted for SNF facility characteristics and county characteristics. For the conditional fixed‐effect logit model, the covariates included were the same as for main analysis. This study was approved by the Research Subjects Review Board of the University of Rochester.

3. RESULTS

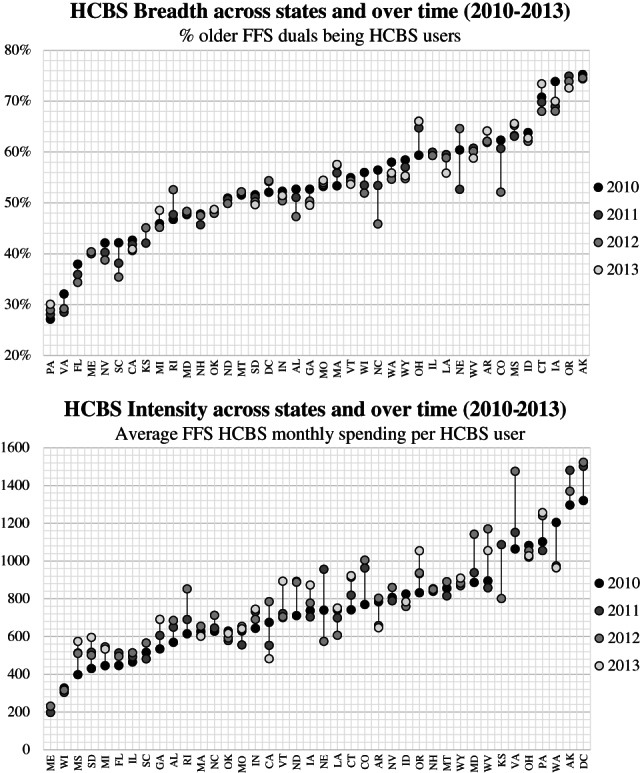

The cross‐sectional and over‐time variation in state‐level HCBS breadth and intensity is displayed in Figure 1. Variation across states was sizable for both HCBS breadth and intensity. For example, in 2012, the HCBS breadth ranged from 29% in Pennsylvania to 75% in Alaska, and the HCBS intensity ranged from $230 in Maine to $1523 in the District of Columbia.

FIGURE 1.

Cross‐state and over‐time variation in Medicaid home‐ and community‐based services (HCBS) breadth and intensity. Eleven states (AZ, DE, HI, KY, MN, NJ, NM, NY, TN, TX, UT) were excluded from this figure due to high penetration of managed care program enrollment or major expansion of managed care programs during study period

Substantial cross‐sectional and over‐time variation in HCBS breadth and intensity were also observed at the county level. In 2012, county‐level HCBS breadth ranged from 18.9% (1st percentile) to 80.0% (99th percentile), and HCBS intensity ranged from $58 (1st percentile) to $1910 (99th percentile). Over the study period from 2010 to 2013, the median within‐county over‐time variation in HCBS breadth was 5.8 percentage points, with 3.5 percentage points and 9.4 percentage points being in the first and the third quartiles. The median within‐county variation in HCBS intensity was $150, and the first and third quartiles were $85 and $252, respectively (numbers not presented in table/figure).

Table 1 compares individual characteristics of duals who were and were not discharged within 100 days. Overall, 49.4% of newly admitted dual SNF residents were discharged within 100 days. Duals who were discharged to the community were younger, more likely to be female, and more likely to be Black or other races. Upon SNF admission, they had lower level of physical and cognitive impairment, were less likely to have mental illness (eg, anxiety, schizophrenia), and fewer clinical conditions (eg, incontinence). They are also less likely to experience hospitalization events in the prior year. For the index hospitalization, duals who were discharged were more likely to be hospitalized for a surgical stay (not medical), had more complex conditions (indicated by higher DRG weights), had a shorter length of stay, and were less likely to be admitted to the ICU during the inpatient stay, as compared to individuals who were not discharged. All individual‐level characteristics were different between duals who were and were not discharged except for hip fracture and bipolar disorder.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for dual SNF users by discharge status

| Variable | Discharged | Not discharged | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 110 765 | n = 113 464 | ||

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age | 78.0 | 80.3 | *** |

| Male | 26.0% | 31.0% | *** |

| Race/Ethnicity | *** | ||

| White | 65.2% | 68.1% | |

| Black | 16.9% | 18.7% | |

| Other | 17.9% | 13.1% | |

| Marital status | *** | ||

| Married | 18.9% | 19.3% | |

| Divorced | 18.8% | 15.1% | |

| Separated | 2.0% | 1.6% | |

| Never married | 14.6% | 14.4% | |

| Widowed | 43.2% | 47.1% | |

| Other | 2.5% | 2.5% | |

| Original reason for Medicare entitlement | *** | ||

| Old age | 73.0% | 76.6% | |

| Disability | 26.4% | 22.7% | |

| ESRD | 0.3% | 0.3% | |

| Disability and ESRD | 0.3% | 0.4% | |

| Characteristics of index hospitalization | |||

| Surgical stay | 36.9% | 23.8% | *** |

| Length of stay (days) | 6.5 | 8.5 | *** |

| DRG weights | 1.8 | 1.7 | *** |

| ICU use | 28.8% | 30.1% | *** |

| Health and functional status | |||

| ADL dependence | 16.3 | 18.5 | *** |

| Cognitive function | *** | ||

| Intact | 59.5% | 32.5% | |

| Mildly impaired | 24.0% | 27.2% | |

| Moderately impaired | 13.5% | 30.3% | |

| Severely impaired | 2.0% | 7.3% | |

| Missing | 1.0% | 2.7% | |

| # of hospital stay in prior 365 days | 0.86 | 0.93 | *** |

| Clinical diagnoses | |||

| Hypertension | 80.3% | 79.4% | *** |

| Anemia | 31.3% | 33.4% | *** |

| ADRD | 19.3% | 38.4% | *** |

| Asthma/COPD | 30.1% | 28.0% | *** |

| Heart failure | 22.8% | 26.1% | *** |

| Anxiety | 19.7% | 21.2% | *** |

| Pneumonia | 11.4% | 14.0% | *** |

| Nonhip fraction | 9.1% | 8.7% | *** |

| Hip fracture | 7.7% | 7.6% | NS |

| Psychotic disorder | 3.0% | 6.3% | *** |

| Malnutrition | 3.0% | 5.2% | *** |

| Schizophrenia | 2.4% | 3.4% | *** |

| Bipolar disorder | 2.6% | 2.5% | NS |

| ESRD | 0.05% | 0.07% | ** |

| Clinical conditions and treatments | |||

| Incontinence | 50.7% | 73.5% | *** |

| Hemiplegia | 3.3% | 5.1% | *** |

| Seizure disorder/epilepsy | 5.0% | 5.7% | *** |

| Shortness of breath with exertion | 17.5% | 18.4% | *** |

| Shortness of breath when sitting | 5.1% | 8.0% | *** |

| Shortness of breath when lying | 9.1% | 11.8% | *** |

| Swallowing problem | 5.2% | 8.7% | *** |

| Weight loss | 8.6% | 9.8% | *** |

| Surgical wound | 32.5% | 19.3% | *** |

| # of days in a week having any injection | 2.9 | 2.4 | *** |

| Any insulin injection | 26.8% | 24.9% | *** |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; ADRD, Alzheimer's disease and related dementia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DRG, diagnosis‐related groups; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; ICU, intensive care unit; NS, not significant; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

P < 0.01.

** P < 0.05.

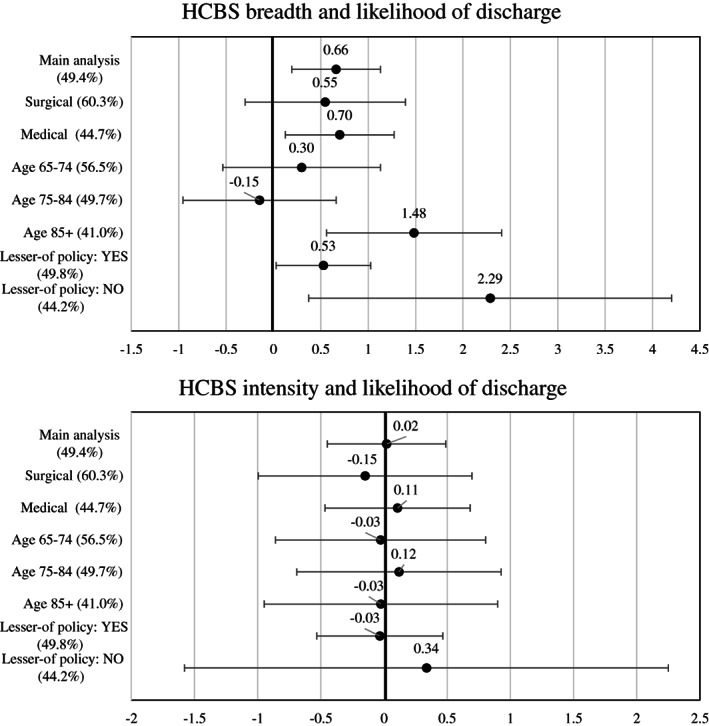

Summarized results from the regression analyses are shown in Figure 2, and the full results for the main model and stratified analyses are presented in Table 2 and Appendix, Tables 1‐1 and 1‐2. The main analysis suggested that a 10 percentage‐point increase in HCBS breadth was associated with a 0.66 percentage‐point increase in the likelihood of discharge among older dual SNF users. However, the relationship between HCBS breadth and community discharge varied among subpopulations. For example, we detected a positive relationship between HCBS breadth and community discharge among medical patients (0.7%, P < 0.05) but not among surgical patients. In addition, the relationship between HCBS breadth and community discharge was significant among the oldest old (individuals aged 85 years and older, 1.5%, P < 0.01) but not among the younger age groups. Medicaid payment policies also affected the relationship between HCBS breadth and the likelihood of community discharge—that is, the presence of a state Medicaid lesser‐of policy reduced the effect size of HCBS breadth on community discharge (2.3% vs 0.5% for states without and with lesser‐of policy). We did not detect a significant relationship between HCBS intensity and community discharge in the main analysis or the stratified analyses. Findings from the sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main analyses (results presented in the Appendix, Tables 2‐1 to 2‐3).

FIGURE 2.

Findings from main analysis and stratified analysis: relationship between Medicaid home‐ and community‐based services (HCBS) breadth/intensity and likelihood of community discharge by day 100. Each line in the figure indicates estimated probability and 95% confidence interval, and the percentage in the parentheses after the model name indicates the mean predicted probability of discharge from the model. Unit for HCBS breadth is 10 percentage points, unit for HCBS intensity is $100, and unit of outcome is 1 percentage point. Eleven states (AZ, DE, HI, KY, MN, NJ, NM, NY, TN, TX, UT) were excluded from this analysis. The full results are presented in the Appendix

TABLE 2.

Association between HCBS generosity (breadth and intensity) and likelihood of community discharge

| Variables | Likelihood of community discharge |

|---|---|

| HCBS breadth | 0.661*** |

| (0.239) | |

| HCBS intensity | 0.0195 |

| (0.0846) | |

| Age | −0.233*** |

| (0.0149) | |

| Male | −4.618*** |

| (0.233) | |

| Race, black | 5.351*** |

| (0.339) | |

| Race, other | 5.790*** |

| (0.343) | |

| Marital status, divorced | −1.110*** |

| (0.345) | |

| Marital status, never married | −2.410*** |

| (0.360) | |

| Marital status, other | −3.373*** |

| (0.715) | |

| Marital status, separated | −0.838 |

| (0.757) | |

| Marital status, widowed | −1.177*** |

| (0.290) | |

| Reason for original Medicare entitlement: Disability | 1.781*** |

| (0.253) | |

| Reason for original Medicare entitlement: ESRD | −8.711*** |

| (1.749) | |

| Reason for original Medicare entitlement: Disability and ESRD | −11.03*** |

| (1.828) | |

| ADL | −1.302*** |

| (0.0269) | |

| CFS: mildly impaired | −9.545*** |

| (0.274) | |

| CFS: moderately impaired | −16.28*** |

| (0.328) | |

| CFS: severely impaired | −18.62*** |

| (0.516) | |

| CFS: missing | −25.43*** |

| (0.714) | |

| Surgical stay | 6.232*** |

| (0.392) | |

| Length of hospital stay | −0.503*** |

| (0.0322) | |

| DRG weights | −0.520*** |

| (0.112) | |

| ICU | 0.533** |

| (0.242) | |

| Hospitalization in prior year | −0.352*** |

| (0.0720) | |

| Anemia | −2.267*** |

| (0.216) | |

| Heart failure | −2.322*** |

| (0.244) | |

| Hypertension | 0.813*** |

| (0.253) | |

| ESRD | 0.890*** |

| (0.263) | |

| ADRD | −6.054 |

| (4.437) | |

| Asthma/COPD | −7.109*** |

| (0.272) | |

| Pneumonia | 1.531*** |

| (0.239) | |

| Hip fracture | 0.197 |

| (0.317) | |

| Other fracture | −1.554*** |

| (0.422) | |

| Malnutrition | −0.0378 |

| (0.355) | |

| Anxiety | −5.500*** |

| (0.534) | |

| Bipolar disorder | −1.394*** |

| (0.250) | |

| Psychotic disorder | −0.374 |

| (0.631) | |

| Schizophrenia | −5.002*** |

| (0.500) | |

| Incontinence | −3.861*** |

| (0.629) | |

| Hemiplegia | −8.219*** |

| (0.254) | |

| Seizure disorder/epilepsy | −2.021*** |

| (0.510) | |

| Shortness of breath with exertion | 2.822*** |

| (0.458) | |

| Shortness of breath when sitting | −0.880*** |

| (0.332) | |

| Shortness of breath when lying | −7.085*** |

| (0.487) | |

| Swallow problem | −2.247*** |

| (0.421) | |

| Weight loss | −2.656*** |

| (0.403) | |

| Surgical wound | −1.618*** |

| (0.251) | |

| # of days having injection | 3.201*** |

| (0.358) | |

| # of days insulin injection | 0.509*** |

| (0.0488) | |

| Insulin injection | −3.736*** |

| (0.367) | |

| Year: 2011 (ref:2010) | 1.288*** |

| (0.358) | |

| Year: 2012 (ref:2010) | 3.188*** |

| (0.373) | |

| Year: 2013 (ref:2010) | 3.970*** |

| (0.454) | |

| Constant | 103.4*** |

| (1.860) | |

| Observations | 224 229 |

| R‐squared | 0.136 |

| Number of SNFs | 11 684 |

Note: Estimates reflect percentage point increases/decreases. Robust SEs in parentheses. Eleven states (AZ, DE, HI, KY, MN, NJ, NM, NY, TN, TX, and UT) were excluded from this analysis.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; ADRD, Alzheimer's disease and related dementia; CFS, cognitive function scale; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DRG, diagnosis‐related groups; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; HCBS, home‐ and community‐based services; ICU, intensive care unit; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

P < 0.01;

P < 0.05.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first national study to explore whether and to what extent an increase in HCBS generosity, measured by breadth and intensity, is associated with the transition from SNF to the community among dual eligible SNF users. This study extends the existing knowledge of HCBS generosity and community discharge by disentangling the roles of HCBS breadth and intensity in the SNF‐community transition. Using 2010 to 2013 national data, we found that greater HCBS breadth was associated with a higher likelihood of community discharge, an effect which varied by subgroups of populations.

However, we did not detect an association between HCBS intensity and community discharge. Individuals may be more sensitive to and aware of HCBS breadth (eg, whether the services will be available or not) than HCBS intensity (eg, how generous the benefit is or the amount of HCBS spending for an average HCBS user in their area). Thus, information on HCBS breadth/coverage could have a greater influence on an individual's decision to return home. On the other hand, HCBS intensity may have a greater influence on facilitating the ability of individuals to remain in the community following SNF discharge.

Our study further suggests that the relationship between HCBS generosity and SNF‐community discharge can be modified by individual factors and state policies. We found HCBS generosity was more likely to be associated with community discharge among SNF residents after a medical inpatient event rather than a surgical event. Most of the surgical patients are likely admitted to the SNF for rehabilitation services, with the expectation to return to the community. Thus, the decision of returning to the community is less likely to be affected by nonclinical factors, for example, the availability of community support. In addition, surgical patients in the study cohort were younger and less likely to have cognitive impairment compared to medical patients, and they may be less likely to need HCBS support to live in the community. We also found that HCBS breadth was related to community discharge among the oldest old, that is, duals aged 85 years and older, but not younger residents. This result is expected, as younger residents may be more likely to be self‐sufficient and less likely to need long‐term care support.

Our findings also suggest that the association between HCBS generosity and SNF‐community discharge could be affected by Medicaid payment policies for SNF services. Discharge decisions can be influenced by the SNFs. 39 Because SNFs in states with lesser‐of policies receive less reimbursement than Medicare rates for day 21 to day 100 of SNF service, up to $148 less per day in 2013, 36 for a dually enrolled individual, SNFs may have stronger incentives to discharge dual residents regardless of HCBS availability. Indeed, we observed a higher rate of discharge in these states vs states with more generous SNF payment policies (49.8% vs 44.2%). Not surprisingly, we found a weaker association of HCBS generosity with community discharge in states with lesser‐of policy for SNFs as compared to states without such (0.5% vs 2.3%). Although this study did not focus on the appropriateness of discharge, future research is needed to explore the relationship between postdischarge outcomes and Medicaid SNF payment policies.

While the effect size of HCBS breadth on facilitating community discharge from SNF is modest for older duals in general (10 percentage point increase in HCBS breadth leads to 0.7 percentage point increase in discharge), our findings highlighted the role of HCBS among some specific groups. For example, the effect size of HCBS breadth was greater for the oldest old (85 years and older) compared to duals in general, and this effect was also greater in states having more generous payment policies for SNFs. Therefore, tailored HCBS policies to increase the coverage for targeted populations or in certain regions may have a stronger effect to promote community discharge.

Given the tremendous growth in Medicaid HCBS in the past couple decades, research examining the effect of HCBS policy among duals is important and timely. This study improved the understanding of to what degree investments in HCBS could replace NH spending for SNF dually eligible residents. Although the findings suggest that improving HCBS generosity may not be an efficient strategy to promote community discharge of dual SNF users in general, targeting vulnerable subgroups of duals could be more effective. This work also provides useful information about resource allocation for HCBS programs, in which trade‐offs exist between providing fewer services to a broader population vs providing more intensive service to the higher‐need population. As our findings suggested a role of HCBS breadth in improving community discharge, broadening HCBS coverage may be considered to promote transitions from SNF to home.

While this study focused on duals with Medicaid FFS coverage, the questions addressed in this study are still of great interest in the current policy environment where states are moving toward Medicaid MLTSS programs. MLTSS programs may be more flexible to tailor the HCBS benefits and to significantly change the coverage and/or the intensity of HCBS for targeted groups, and this change may affect community discharge considerably. In addition, to support duals' living in the community, managed care programs may also adopt other strategies such as prioritizing postacute home health rather than SNF care and incentivizing SNFs to promote timely discharge.

This study has several limitations. First, although the HCBS generosity measures are intended to capture features of HCBS policy, they were constructed based on service utilization, which also depends on factors such as population demand. However, this is not a major concern because this study was focused on time‐varying HCBS generosity rather than cross‐sectional comparisons, and population demand was not likely to significantly change over the study period. More specifically, we checked the distribution of age and prevalence of chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, stroke, ADRD, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]) among older duals over the study period and found these variables were stable across years. Second, the results may be affected by other HCBS‐related policy changes during the study period. For example, the Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration aimed to facilitate the transition to community for nursing home long‐stayer residents and may have a spillover effect on SNF postacute care residents. Because only time‐varying policy changes may affect the findings of this study and the new MFP grantee states (granted in 2011 and 2012) enrolled a relatively small number of individuals during our study period (1969 enrollees by the end of 2013), 40 , 41 we think the influence from MFP on our findings should be minimal. Third, because the data for Medicaid HCBS eligibility were not available, we were not able to use HCBS‐eligible duals as the denominator for HCBS breadth measure. Alternatively, we used all older duals (broader than HCBS‐eligible duals) as the denominator in the main analysis and dual eligible LTSS users (stricter than HCBS eligible duals) in sensitivity analysis, and findings were consistent. Fourth, while the time frame we use (100 days) for our measure of community discharge is standard, it is possible that HCBS affects discharge after residents' transition to long‐stay status. And fifth, while this study used data before 2013, the relationship between HCBS generosity and community discharge should still hold today. It should be noted that the vast majority of duals were under Medicaid FFS coverage during the study period, and this study focused on HCBS provided on an FFS basis. The findings of this study may not be directly applied to duals who were enrolled in Medicaid managed care programs.

In conclusion, we measured county‐level HCBS generosity by its breadth and intensity, and explored its relationship with SNF‐community discharge among dually enrolled older adults. We found that higher HCBS breadth but not intensity was associated with greater likelihood of community discharge and that the relationship between HCBS breadth and community discharge could be modified by factors such as age, type of index hospitalization, and presence of lesser‐of policies for SNF. Future studies are needed to examine the effect of different types of HCBS, and to explore the role of HCBS breadth and intensity on patients' outcomes following community discharge to better serve this vulnerable population.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support for this work from the National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG052451 (PI: Cai). The authors have no other disclosures.

Wang S, Temkin‐Greener H, Simning A, Konetzka RT, Cai S. Medicaid home‐ and community‐based services and discharge from skilled nursing facilities. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(6):1156–1167. 10.1111/1475-6773.13690

Funding information National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R01AG052451

REFERENCES

- 1. CMS . 2016. CMS Statistics. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMS-Statistics-Reference-Booklet/Downloads/2016_CMS_Stats.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 2. Kane RL, Kane RA. What older people want from long‐term care, and how they can get it. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):114‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Binette J, Vasold K. Home and community preferences: a national survey of adults age 18‐plus. AARP Res. Washington, DC: AARP Research; 2018. 10.26419/res.00231.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. MedPAC . Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_entirereport_sec_rev_0518.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Published 2018. Updated March. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 5. Arling G, Kane RL, Cooke V, Lewis T. Targeting residents for transitions from nursing home to community. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):691‐711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guo J, Konetzka RT, Magett E, Dale W. Quantifying long‐term care preferences. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):106‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meador R, Chen E, Schultz L, Norton A, Henderson C Jr, Pillemer K. Going home: identifying and overcoming barriers to nursing home discharge. Care Manag J. 2011;12(1):2‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gassoumis ZD, Fike KT, Rahman AN, Enguidanos SM, Wilber KH. Who transitions to the community from nursing homes? Comparing patterns and predictors for short‐stay and long‐stay residents. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2013;32(2):75‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coughlin TA, McBride TD, Perozek M, Liu K. Home care for the disabled elderly: predictors and expected costs. Health Serv Res. 1992;27(4):453‐479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mistiaen P, Duijnhouwer E, Wijkel D, de Bont M, Veeger A. The problems of elderly people at home one week after discharge from an acute care setting. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(6):1233‐1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Komisar HL, Feder J, Kasper JD. Unmet long‐term care needs: an analysis of medicare‐medicaid dual eligibles. INQUIRY. 2005;42(2):171‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MedPAC . A Data Book: Health Care Spending and The Medicare Program. MedPAC. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun17_databookentirereport_sec.pdf. Published 2017. Updated June. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 13. MedPAC . Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar13_entirereport.pdf. Published 2013. Updated March. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 14. Cai Q, Salmon JW, Rodgers ME. Factors associated with long‐stay nursing home admissions among the U.S. elderly population: comparison of logistic regression and the cox proportional hazards model with policy implications for social work. Soc Work Health Care. 2009;48(2):154‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Howell S, Silberberg M, Quinn WV, Lucas JA. Determinants of remaining in the community after discharge: results from New Jersey's nursing home transition program. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):535‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martikainen P, Moustgaard H, Murphy M, et al. Gender, living arrangements, and social circumstances as determinants of entry into and exit from long‐term institutional care at older ages: a 6‐year follow‐up study of older finns. Gerontologist. 2009;49(1):34‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rahman M, Tyler D, Thomas KS, Grabowski DC, Mor V. Higher medicare SNF care utilization by dual‐eligible beneficiaries: can medicaid long‐term care policies be the answer? Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):161‐179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ng T, Harrington C, Musumeci M, Ubri P. Medicaid Home and Community‐Based Services Programs: 2013 Data Update. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid‐home‐and‐community‐based‐services‐programs‐2013‐data‐update/. Accessed May 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid and Long‐Term Services and Supports: A Primer. http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer. Published 2015. Updated December. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 20. Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, Feng Z, Intrator O, Grabowski DC. Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Aff. 2007;26(6):1762‐1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Segelman M, Intrator O, Li Y, Mukamel D, Veazie P, Temkin‐Greener H. HCBS spending and nursing home admissions for 1915 (c) waiver enrollees. J Aging Soc Policy. 2017;29(5):395‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Muramatsu N, Yin H, Campbell RT, Hoyem RL, Jacob MA, Ross CO. Risk of nursing home admission among older americans: does states' spending on home‐and community‐based services matter? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(3):S169‐S178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burr JA, Mutchler JE, Warren JP. State commitment to home and community‐based services: effects on independent living for older unmarried women. J Aging Soc Policy. 2005;17(1):1‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arling G, Abrahamson KA, Cooke V, Kane RL, Lewis T. Facility and market factors affecting transitions from nursing home to community. Med Care. 2011;49(9):790‐796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu H, Intrator O. Medicaid long‐term care policies and rates of nursing home successful discharge to community. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;21(2):248‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kemper P, Weaver F, Short PF, Shea D, Kang H. Meeting the need for personal care among the elderly: does medicaid home care spending matter? Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1p2):344‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. CMS . Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) General Information ‐ MAX TAF Availability Matrix. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MAXGeneralInformation. Published 2019. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 28. Brown University . Shaping Long Term Care in America Project at Brown University Funded in Part by the National Institute on Aging (1P01AG027296). http://ltcfocus.org/. Accessed July 2020.

- 29. RTI International . MDS 3.0 Quality Measures User's Manual. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS‐30‐QM‐Users‐Manual‐V11‐Final.pdf. Published 2017. Updated April. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 30. Goncalves J, Weaver F, Konetzka RT. Measuring state Medicaid home care participation and intensity using latent variables. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;39(7):731‐744. 10.1177/0733464818786396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol Ser A. 1999;54(11):M546‐M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The minimum data set 3.0 cognitive function scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. CMS . Nursing Home Compare Claims‐Based Quality Measure Technical Specifications. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider‐Enrollment‐and‐Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/Nursing‐Home‐Compare‐Claims‐based‐Measures‐Technical‐Specifications.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 34. Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, et al. Use of hospital‐based acute care among patients recently discharged from the hospital. Jama. 2013;309(4):364‐371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burke RE, Juarez‐Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post‐acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. MACPAC . Medicaid Coverage of Premiums and Cost Sharing for Low‐Income Medicare Beneficiaries. MACPAC. Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP Website. https://www.macpac.gov/wp‐content/uploads/2013/03/Medicaid‐Coverage‐of‐Premiums‐and‐Cost‐Sharing‐for‐Low‐Income‐Medicare‐Beneficiaries.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- 37. Eiken S, Sredl K, Burwell B, Woodward R. Medicaid Expenditures for Long‐Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2015. Cambridge, MA: Truven Health Analytics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eiken S, Sredl K, Gold L, Kasten J, Burwell B, Saucier P. Medicaid Expenditures for Long‐Term Services and Supports in FFY 2012. Bethesda, MD: Truven Health Analytics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hackmann MB, Pohl RV. Patient vs. Provider Incentives in Long Term Care. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25178/w25178.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Irvin C, Denny‐Brown N, Bohl A, et al. Money follows the person 2015 annual evaluation report. Mathematica Policy Research; 2017:9‐12. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2019‐12/mfp‐2015‐annual‐report.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Medicaid.gov. Total MFP Grant Awards and Initial Award Dates. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2020‐01/mfp‐grant‐awards‐12162019.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed April 4, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.