Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are responsible for therapy resistance and share several properties with normal stem cells. Here, we show that brain‐expressed X‐linked gene 2 (BEX2), which is essential for dormant CSCs in cholangiocarcinoma, is highly expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) lesions compared with the adjacent normal lesions and that in 41 HCC cases the BEX2high expression group is correlated with a poor prognosis. BEX2 localizes to Ki67‐negative (nonproliferative) cancer cells in HCC tissues and is highly expressed in the dormant fraction of HCC cell lines. Knockdown of BEX2 attenuates CSC phenotypes, including sphere formation ability and aldefluor activity, and BEX2 overexpression enhances these phenotypes. Moreover, BEX2 knockdown increases cisplatin sensitivity, and BEX2 expression is induced by cisplatin treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that BEX2 induces dormant CSC properties and affects the prognosis of patients with HCC.

Keywords: BEX2, cancer stem cell, dormant, hepatocellular carcinoma, prognosis

BEX2 is essential for dormant cancer stem cell and affects patients’ prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. BEX2 could be a promising therapeutic target.

![]()

Abbreviations

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- BEX2

brain‐expressed X‐linked gene 2

- CCD

charge‐coupled device

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- MTT

3‐(4,5‐di‐methylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PE

phycoerythrin

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TBS

tris‐buffered saline

1. INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary liver cancer, 1 the sixth most common neoplasm, and the third leading cause of death among patients with cirrhosis; its incidence is expected to increase worldwide. 2 Although there are several treatment options for patients with HCC (surgical resection, transplantation, ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, etc.), only a few effective treatments are available for advanced cases.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are considered to be responsible for maintaining the whole population of cells and therapy resistance in tumors; thus, cancer stem cell–targeting therapy is a promising anticancer strategy. 3 CSCs share numerous properties with normal stem cells, such as CD90 expression, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, and a relative dormancy. 4 In HCC, CSCs have been explored intensively and many surface markers have been discovered, including CD90, 5 CD24, 6 EpCAM, 7 and CD13. 8 CD13 is a marker of semiquiescent CSCs in HCC. 8 However, the precise mechanisms underlying the maintenance of dormant CSC phenotypes in HCC remain largely unknown.

Recently, we identified brain‐expressed X‐linked 2 (BEX2), which interacts with mitochondrial protein TUFM, and is essential for dormant CSCs in cholangiocarcinoma by suppressing mitochondrial function after a screening of CSC‐related genes. 9 BEX2 belongs to the BEX gene family and was initially identified as a homolog of the BEX1 gene. 10 The functional domains of BEX2 remain poorly understood; however, a previous report suggested that it acts as a regulator of embryonic development by modulating the transcriptional activity of an E‐box sequence‐binding complex that contains BEX2 and LMO2 in vitro. 11 BEX2 is implicated in several cancers in addition to cholangiocarcinoma, including glioma 12 and breast cancer, 13 through the c‐Jun and NF‐κB pathways. Moreover, BEX2 is expressed in stem/progenitor cells of the normal fetal liver. 14 These data led us to hypothesize that BEX2 plays significant roles in liver CSCs.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the role of BEX2 in CSCs in HCC. We studied BEX2 expression in surgical specimens and examined the role of BEX2 in HCC cell lines.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and tissue specimens

This study included 41 consecutive patients with HCC who underwent surgical resection at the Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital between January 2008 and June 2018. Cases where most of the specimens showed necrotic areas were excluded. We reviewed the patients' medical records for the following clinicopathological factors: age, sex, pathological T classification, tumor size, Child‐Pugh score, alpha‐fetoprotein, and pathological stage. All cases were classified histopathologically according to the 7th edition of the UICC TNM staging system. All patients gave written informed consent for inclusion in the study.

2.2. Analysis of TCGA dataset

From TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), we collected expression data on 362 cases in the Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (LIHC) dataset as Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM). Out of 362 samples, 50 cases had both cancer and adjacent normal tissue expression data. For Kaplan‐Meier analysis, 362 cases were used.

2.3. Analysis of the GEO dataset

The expression datasets GSE25097, GSE76427, and GSE103866 were exported from the GEO website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) and analyzed using R software and its packages (Affy, RobLoxBioC, and Seurat).

2.4. Cells

HLE (human HCC) cells were provided by the National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health, and Nutrition (Osaka, Japan). Huh‐7 cells (human HCC) were a kind gift from Dr. Chisari (The Scripps Research Institute). These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin‐streptomycin (Wako). All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma and characterized by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling.

For establishment of BEX2‐overexpressing cells, HLE and Huh‐7 cells were transfected with human BEX2‐expressing PB‐CMV‐MCS‐EF1‐Puro vector (PB‐BEX2) as previously described. 9 The empty vector (PB‐EV) was used for establishment of control cells. hBEX2 cDNA was obtained from RIKEN BRC (pCMV‐SPORT6‐hBEX2), and added a sequence (atgcagaaaatggtg) at the beginning of a coding region to make the same sequence to the transcript variant 1 (NM_001168399.2). The cells were selected with puromycin, and established as HLE‐PB‐BEX2, Huh‐7‐PB‐BEX2, HLE‐PB‐EV, and Huh‐7‐PB‐EV cells.

2.5. Gene expression profiling

Expression profiling of HLE‐PB‐EV and HLE‐PB‐BEX2 was performed using microarray (SurePrint G3 8x60k, Agilent) as previously described. 15 Data processing was performed using R statistical software (version 4.1.0) and GSEA software. 16

2.6. Cloning of BEX2 promoter region

The promoter region of BEX2 was cloned from the genome of the HuCCT1 cell line (cholangiocarcinoma, provided by RIKEN BioResource Center) by PCR‐based method. EGFP cDNA was cloned from the pEGFP‐C2 vector (Takara Bio USA). To construct a vector without a promoter, the CMV promoter was deleted from the PB‐CMV‐MCS‐EF1‐Puro vector (SBI). A 2‐kbp region of the BEX2 promoter and EGFP was inserted into the CMV promoter–deleted PB‐CMV‐MCS‐EF1‐Puro vector (PB‐2k‐EGFP). The primers used for the promoter cloning were forward‐CTGCAGACGGCCGGGGTGGG and reverse‐TATTTACTCCCAGCTTCTCA. HLE cells were transfected with the PB‐2k‐EGFP plasmid and piggy bac transposase (SBI). The cells were selected with puromycin (1 µg/ml) and established as HLE‐2k‐EGFP cells.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously. 9 Briefly, heat‐induced epitope retrieval was performed in a target‐retrieval solution (Immunosaver, Nissin EM). First antibodies used are anti‐Ki67 rabbit monoclonal antibody (ab16667, Abcam, 1:100) or anti‐BEX2 mouse monoclonal antibody (sc‐398486, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:800) diluted in Dako REAL (S2022, Dako), and a second antibody is EnVision Flex HRP. For Kaplan‐Meier analysis, the cases were divided into two groups according to the BEX2‐positive area (BEX2high, >50% area BEX2 positive in tumor area; BEX2low, remaining cases). BEX2‐positive area was defined when the staining intensity of BEX2 in the tumor area was determined to be greater than the background intensity in low‐power fields by two experts.

For double staining of BEX2 and Ki67, we used the Tyramide SuperBoost kits (Invitrogen) to enhance the BEX2 signal. Specimens were blocked with blocking buffer for 1 hour, and incubated at 4°C for 16 hours with an anti‐BEX2 mouse monoclonal antibody (sc‐398486, 1:500) or anti‐Ki67 rabbit monoclonal antibody (ab16667, 1:300) diluted in Dako REAL. Bound antibodies were probed with an HRP‐conjugated antibody for 60 minutes at 25°C and treated with tyramide solution for 5 minutes. Slides were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti‐rabbit IgG antibody (Invitrogen, 1:200) for 60 minutes at room temperature.

2.8. Immunocytochemistry

HLE‐2k‐EGFP cells were fixed with 4% formalin for 20 minutes at room temperature. The cells were treated with Image‐iT FX Signal Enhancer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 minutes, washed with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X, and incubated with primary antibodies (anti‐Ki67, 1:100, SP6, Abcam; and anti‐BEX2, 1:100, C12, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The cells were then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:200, anti‐mouse Alexa 488 and anti‐rabbit Alexa 594, ThermoFisher) and DAPI (4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole, 1 µg/mL, Dojindo) for 60 minutes at room temperature. Images were randomly obtained using NikonA1 microscope (Nikon).

2.9. Sphere formation assay

A total of 5 × 103 cells were seeded in Nunclon Sphera 96‐well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in DMEM/F12 medium containing B27 supplement, EGF (20 ng/mL, PeproTech), FGF‐2 (20 ng/mL, PeproTech), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Wako). The cells were cultured for 4‐7 days, and phase‐contrast images were obtained using NikonA1 (Nikon). The areas of the spheres were measured using ImageJ software.

2.10. Organoid formation assay

A total of 2.5 × 103 cells were suspended in 20 μL Matrigel before being seeded in Matrigel‐coated 96‐well plates with medium (DMEM/F12 medium containing HEPES, penicillin/streptomycin, Glutamax [2 mM], N2 supplement, B‐27 supplement, and NAC [1 mM]). The cells were cultured for 8 days, and phase‐contrast images were obtained using Nikon A1 (Nikon). The areas of the organoids were measured using ImageJ software.

2.11. Small interfering RNAs

Nonsilencing control siRNA (12935‐300) and BEX2 siRNA #1 (HSS131257) and #2 (HSS131258) were purchased from Invitrogen. The siRNA transfections were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Life Technologies) in antibiotic‐free medium for 48 hours. The siRNA knockdown efficiencies were confirmed using real‐time PCR and Western blotting.

2.12. Quantitative real‐time PCR

Quantitative real‐time PCR was performed as described previously. 17 The primer pairs used were BEX2: GCCCCGAAAGTAGGAAGC, CTCCATTACTCCTGGGCCTAT; SOX2: TGGCTCCATGGGTTCGGTGG, TGTGAAGTCTGCTGGGGGCG ACTB: CCAACCGCGAGAAGATGA, TCCATCACGATGCCAGTG.

For the quantification of BEX2 mRNA in pyronin low and high fractions, the cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (5 µg/ml, Sigma‐Aldrich) and pyronin Y (0.4 µg/mL, Sigma‐Aldrich) for 60 minutes at 37°C. After washing with complete medium, the cells were sorted according to the pyronin Y intensity by FACS AriaII (BD Biosciences). A hundred of cells were collected in 1 µL lysis buffer (0.5% NP40 [Sigma‐Aldrich], 1 U/µL RNase inhibitor [Takara]), and cDNA was synthesized using Super Script IV VILO master mix (ThermoFisher) as described previously. 18

2.13. Aldefluor assay

ALDH activities were determined using Aldefluor assay (STEMCELL Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.14. Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle analysis, cells were trypsinized and then fixed with 70% ethanol at −20°C. The fixed cells were stained with anti‐Ki67 (1:9, Biolegend) and 10 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI). The stained cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (SA3800, Sony). The data were analyzed by FlowJo (BD biosciences) or CytoExploreR package on R software. 19 , 20

2.15. 3‐(4,5‐di‐methylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

A total of 5 × 103 HLE or 2 × 103 Huh‐7 cells were plated in 0.1 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin‐streptomycin in a 96‐well plate. At the indicated times, MTT assay reagent (Roche) was added to each well according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance at 575 nm and 650 nm (background measurement) was determined using a plate reader (VersaMax ELISA microplate Reader, Molecular Devices). At least three replicate wells were assayed for each condition, and the standard deviation was determined.

For cisplatin sensitivity assay, the cells were treated with siRNA against BEX2, and after two days, cisplatin (Wako) was added at the indicated concentration. The MTT assay was performed four more days later.

2.16. Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously. 17 The primary antibodies used in this study were anti‐BEX2 (D6, 1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti‐alpha‐tubulin‐HRP‐DirecT (1:2000, MBL).

2.17. In vivo tumorigenesis

The tumor formation assay was performed as described previously. 17 Briefly, the cells were suspended in 50 µL of PBS and an equal volume of Matrigel matrix (BD Biosciences) at 4ºC, and then injected into NOG mice with a 1‐mL syringe. Tumor formation was monitored weekly. The tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: 1/2 (length × width × height).

2.18. Statistical analysis

All data obtained from cell lines were analyzed for statistical significance by Student's t‐test using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.4.2; GraphPad Software), and P < .05 was considered significant.

For Kaplan‐Meier analysis, recurrence‐free survival was defined as the number of days from the date of surgery to the date of death, recurrence, or final confirmation of survival. Statistical tests were performed using JMP (version 14.2.0), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

For the evaluation of double‐staining for Ki67 and BEX2 in HCC tissues, we randomly selected 11 cases, and the expected values of double‐positive cells were calculated as the actual BEX2 single‐positive cell ratio × the actual Ki67 single‐positive ratio; then, a one‐sample t‐test was performed between the expected and actual values using R (version 4.0.2). 19 P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. BEX2 is highly expressed in HCC and is a negative prognostic factor

To explore the role of BEX2 in HCC, we first examined BEX2 expression using immunohistochemistry in tumor specimens. We divided the HCC cases into two groups according to the percentage of BEX2‐positive areas: BEX2high and BEX2low (≥50% positive area and <50% positive area, respectively). The BEX2high group comprised 17/41 patients (Table 1). In BEX2high cases, the expression level of BEX2 was higher in HCC than in the adjacent normal liver (Figure 1A,B). Furthermore, we investigated the TCGA dataset and found that BEX2 mRNA expression was significantly higher in tumors than in adjacent normal specimens (Figure 1C). Our analysis of human hepatocellular expression array data from GEO also found that BEX2 mRNA expression was significantly higher in tumors than in nontumor or adjacent normal specimens (Figure 1D,E). Table 1 summarizes the clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients. None of the clinical characteristics correlated with the expression of BEX2. Kaplan‐Meier analysis of relapse‐free survival showed significantly shorter survival in the BEX2high group than in the BEX2low group (Figure 1F). We analyzed the correlation between clinical characteristics and relapse‐free survival and calculated the hazard ratio (HR). Relapse‐free survival was correlated with BEX2 expression, number of tumors, T factor, vascular invasion, and stage (Table 2). We then introduced these factors into a Cox regression model for multivariate analysis of relapse‐free survival. We found that relapse‐free survival was significantly correlated with BEX2 expression and vascular invasion. We also analyzed the prognosis using the TCGA dataset. We divided the cases into two groups as BEX2high and BEX2low (≥0.12 and <0.12 FPKM, respectively). Kaplan‐Meier analysis indicated that the BEX2high group showed shorter survival outcomes than the BEX2low group (Figure 1G). These data indicate that BEX2 is a negative prognostic factor in HCC and that it could play an important role in HCC.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

| Characteristics | BEX2low | BEX2high | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 17 | |||

| Age | Mean ± SD (range) | 69.50 ± 12.28 | 67.06 ± 6.07 | .5303 |

| <70/≧70 | 11/13 | 10/7 | ||

| Gender | M/F | 21/3 | 14/3 | .6786 |

| Number of tumors | Single | 20 | 4 | .4500 |

| Multiple | 12 | 5 | ||

| Tumor size | Mean ±SD (range) | 39.21 ± 19.01 | 31.65 ± 13.63 | 1.0000 |

| <20/≧20 | 5/19 | 3/14 | ||

| T factor | 1 | 18 | 10 | .3220 |

| 2‐4 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Vascular invasion | − | 20 | 12 | .4500 |

| + | 4 | 5 | ||

| Differentiation | Low‐medium | 17 | 9 | .3281 |

| High | 7 | 8 | ||

| Postoperative recurrence | − | 14 | 6 | .2082 |

| + | 10 | 11 | ||

| Child‐Pugh class | A/B | 22/2 | 16/1 | 1.0000 |

| AFP | <20 | 18 | 10 | .3220 |

| ≧20 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Stage | 1 | 18 | 10 | .3220 |

| 2‐4 | 6 | 7 | ||

P‐values are calculated using Chi‐square test.

FIGURE 1.

BEX2 is highly expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). A, Representative image of hematoxylin and eosin staining (left panel) and immunohistochemistry of BEX2 (right panel) in surgical resection specimens of human HCC. Brown staining indicates BEX2‐positive cells. Bar, 1 mm. B, Summary of BEX2 positivity in immunohistochemistry using the Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University (TMPU) dataset. The intensity of BEX2 in BEX2high cases (17/41) was measured using ImageJ. The data are shown as the mean intensity of the tumor divided by adjacent normal area. Horizontal solid lines indicate mean ± standard deviation. C, BEX2 mRNA expression levels in The Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA‐LIHC) dataset. A total of 50 cancer cases were collected, and the values were calculated as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million (FPKM) in tumor minus FPKM in the corresponding normal tissue. D, E, BEX2 mRNA expression levels from GSE25097 or GSE76427 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Number of cases: GSE25097: 6 (healthy), 40 (cirrhotic), 243 (adjacent nontumor), and 267 (tumor); GSE76427: 52 (adjacent nontumor) and 115 (tumor). Red lines indicate mean value. F, Kaplan‐Meier analysis for relapse‐free survival of the BEX2high (17 cases) and BEX2low (24 cases) groups. P‐value was calculated using the log‐rank test. G, Kaplan‐Meier analysis for overall survival of the BEX2high (289 cases) and BEX2low (73 cases) groups (≥0.12 and <0.12 FPKM, respectively) in the TCGA dataset. P‐value was calculated using the log‐rank test

TABLE 2.

Association between survival rate and clinicopathological variables

| Variables | Number of cases | Univariate analysis P‐value | HR | Multivariate analysis, 95% CI | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEX2 | ± | 17/24 | .0479 | 2.73 | 1.06‐7.02 | .0373 |

| Number of tumors | Multiple/single | 9/32 | .0329 | 1.74 | 0.39‐7.80 | .4692 |

| T factor | 1/2‐4 | 28/13 | .0004 | 2.23 | 0.46‐10.91 | .3217 |

| Vascular invasion | ± | 9/32 | <.0001 | 5.25 | 1.48‐18.60 | .0102 |

| Stage | 1/2‐4 | 28/13 | .0004 | – | – | – |

Univariable analysis is performed by log‐rank test and multivariate analysis by Wald test in Cox's proportional hazards model. Italics mean P < 0.05.

3.2. BEX2 is expressed in nonproliferative cells

Next, we investigated BEX2 localization in the surgical HCC specimens by immunohistochemistry. We stained randomly 11 selected cases, and the average number of BEX2‐positive cancer cells was 7.1% (Table S1). Because BEX2 is known to be expressed in normal liver stem cells, 14 which are usually dormant, we also stained the specimens with Ki67, a well‐known proliferative marker. In six out of 11 cases, the number of actual BEX2+Ki67+ double‐positive cells was significantly lower than expected (Figure 2A, Table S1), and no case had a significantly higher actual BEX2+Ki67+ value than expected, suggesting that BEX2+ cells are nonproliferative cells in HCC. Further, we examined the relationship between BEX2 and Ki67 expression in HLE cells. To clearly detect endogenous BEX2, we established HLE‐2k‐EGFP cells, in which EGFP was expressed under BEX2 promoter activity (Figure S1). We found that the BEX2+Ki67‐ or BEX2‐Ki67+ cells were dominant, and BEX2+Ki67+ double‐positive cells were minimal (Figure 2B), which was consistent with the immunohistochemistry results. We further confirmed these results using a public single‐cell RNAseq database (GSE103866). We found that in HCC cancer cells, BEX2 and MCM7, a well‐known proliferative marker, were mutually exclusive (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

BEX2‐positive cells are nonproliferative. A, Surgical resection specimens in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were stained with anti‐BEX2 and anti‐Ki67 antibodies, and the EGFP‐ and Ki67‐positive cells were counted. Arrowheads indicate BEX2‐ or Ki67‐positive cancer cells. Bar, 50 µm. B, HLE‐2k‐EGFP cells were stained with anti‐Ki67 antibody, and the EGFP‐ and Ki67‐positive cells were counted. A total of 11 randomly selected areas were analyzed (right panel, P < .00001, Chi‐square test). Bar, 50 µm. C, Expression patterns of BEX2 and MCM7 in HCC cells. A single‐cell RNAseq database (GSE103866, including Huh‐1, Huh‐7, and patient‐derived circulating tumor cells) was analyzed using a Seurat package

To confirm BEX2 localization to dormant cells, we compared BEX2 expression between dormant and cycling cells. Because the pyronin‐low fraction indicates dormant cells, 21 the cells were stained with pyronin Y (RNA content) and Hoechst33342 (DNA content) and sorted according to the pyronin intensity (Figure 3A). We found that BEX2 mRNA expression was significantly higher in the pyronin Y–low fraction in both HLE and Huh‐7 cells (Figure 3B). We further tested the alterations in BEX2 expression under starvation conditions. Serum starvation conditions are known to induce dormant cells (Figure 3C). We found that BEX2 expression was increased in HLE and Huh‐7 cell lines under starvation conditions (Figure 3D). Taken together, these results suggest that BEX2 is predominantly expressed in dormant cancer cells.

FIGURE 3.

BEX2 is predominantly expressed in dormant cancer cells. A, Representative data of flow cytometry analysis of HLE cells. HLE cells were stained with pyronin Y and Hoechst33342. Sorted fractions (pyronin high and low) were reanalyzed by flow cytometry. B, Real‐time PCR of sorted HLE and Huh‐7 cells. The cells were sorted and divided into two groups, pyronin Y‐high and pyronin Y‐low, and total RNA was extracted. C, Cell cycle analysis of HLE and Huh‐7 cells grown under serum starvation conditions (24 h for HLE and 72 h for Huh‐7 cells). The open square indicates dormant cell fraction. PI, propidium iodide. D, Real‐time PCR analysis of BEX2 mRNA expression under starvation condition. The expression was normalized using ACTB (n = 3, *P < .05)

3.3. Knockdown of BEX2 attenuates CSC phenotypes in HCC cell lines

Based on previous findings that BEX2 is predominant in dormant cells and related to CSC phenotypes, 9 we hypothesized that BEX2 plays an important role in HCC dormant CSCs. To clarify this, we established BEX2‐knockdown cell lines by introducing siRNA against BEX2 in HLE and Huh‐7 cells and established BEX2‐overexpressing cells (Figure 4A). Expression microarray analysis using HLE‐PB‐EV and HLE‐PB‐BEX2 cell lines found alterations of Notch and Wnt‐beta‐catenin signaling, which are well‐known for maintaining CSC self‐renewal (Figure S2), suggesting that BEX2 is involved in the CSC‐maintaining pathway.

FIGURE 4.

BEX2 is required for spheroid formation. A, Western blotting analysis of BEX2 expression levels in BEX2‐knockdown HLE and Huh‐7 cells and in BEX2‐overexpressing HLE and Huh‐7 cells. EV, empty vector. B, Cell proliferation capability determined by MTT assay in BEX2‐knockdown and control cells (n = 5, *P < .05 [siControl vs. siBEX2#1 and siControl vs. siBEX2#2]). C, Real‐time PCR analysis of the mRNA expression of BEX2 and SOX2. The cells were cultured in normal or sphere‐forming medium for 3 d and harvested (n = 3, *P < .05). D, Sphere formation assay after siRNA‐mediated depletion or overexpression of BEX2 in HLE and Huh‐7 cells. Total area of spheroid cells was measured using ImageJ (n = 5, *P < .05). E, Organoid formation assay in Huh‐7‐PB‐EV and Huh7‐PB‐BEX2 cells. Total area of spheroid cells was measured using ImageJ (n = 5, *P < .05)

First, we compared the expression of BEX2 under normal growth conditions (Figure 4B). In HLE cells, BEX2 knockdown and BEX2 overexpression slightly decreased proliferation ability. In Huh‐7 cells, BEX2 knockdown caused a weak enhancement of proliferation, and BEX2 overexpression was not affected. Next, we checked the sphere‐forming conditions to test the stem cell properties. Expression of SOX2, a known stemness marker, and BEX2 were significantly increased in spheroid cells compared with control cells (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we performed a sphere‐forming assay using BEX2 knockdown and control cells. BEX2 knockdown reduced spheroid tumor proliferation in both HLE and Huh‐7 cells and vice versa in BEX2‐overexpressing cells (Figure 4D). Analysis of organoid formation using Huh‐7‐PB‐BEX2 and Huh‐7‐PB‐EV (HLE cells did not form typical organoids) showed significantly higher total organoid areas in Huh‐7‐PB‐BEX2 than Huh‐7‐PB‐EV (Figure 4E). Additionally, we tested whether a tumorigenic activity, which is known as a CSC property, is altered by BEX2 depletion. Palpable tumors developed in four mice injected with control HLE cells within 3 weeks, but in only one out of six mice injected with BEX2‐knockdown cells within 8 weeks; similar results were obtained using Huh‐7 cells (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Tumorigenic activity in NOG mice subcutaneously injected with BEX2‐knockdown or control HLE (1 × 107 cells/site) or Huh‐7 cells (1 × 104 cells/site)

| Tumorigenic activity of BEX2‐knockdown cells | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLE | Weeks after injection | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| siControl (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| siBEX2#1 (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| siBEX2#2 (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Huh‐7 | Weeks after injection | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| siControl (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| siBEX2#1 (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| siBEX2#2 (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

Tumor sizes are monitored weekly.

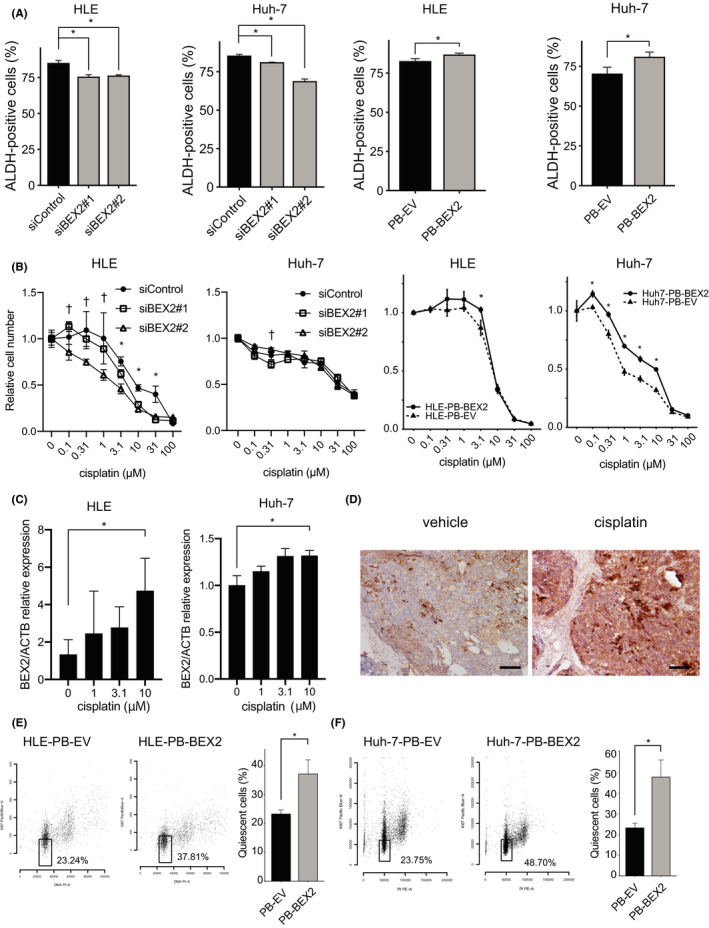

We performed the aldefluor assay, which detects an increase in ALDH activity in CSCs, and found that ALDH activity was decreased by BEX2 knockdown in both the HCC cell lines, while BEX2‐overexpressing cells exhibited higher ALDH activity (Figure 5A). Furthermore, to investigate the role of BEX2 in chemotherapy resistance, we tested the sensitivity of BEX2‐depleted HCC cells to cisplatin, which is widely used in HCC treatment. In HLE cells, BEX2 knockdown increased the sensitivity of HLE cells to cisplatin, but the difference was minimal in Huh‐7 cells (Figure 5B). BEX2‐overexpressing cells showed cisplatin resistance in both cell lines (Figure 5B). BEX2 expression upon cisplatin treatment was clearly increased in HLE cells and modestly in Huh‐7 cells (Figure 5C). We also tested BEX2 expression after cisplatin treatment in vivo. Huh‐7‐PB‐BEX2 tumors expressed more BEX2 protein after cisplatin treatment than tumors that were not treated (Figure 5D). Finally, BEX2 overexpression significantly increased the quiescent cell population in both HLE and Huh‐7 cells (Figure 5E,F). Collectively, these data suggest that BEX2 is required for maintaining dormant CSC phenotypes.

FIGURE 5.

BEX2 plays roles for aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, resistance to CDDP, and quiescent phase. A, ALDH activity was determined by aldefluor assay (n = 3). *P < .05. B, MTT assay analysis to measure cell viability in cells treated with cisplatin at the indicated concentration (n = 5). The duration of cisplatin treatment was 4 d (HLE, siRNA), 2 d (Huh‐7, siRNA), and 6 d (BEX2‐overexpressing cells). *P < .05 in siControl vs. siBEX2#1 and siControl vs. siBEX2#2; PB‐EV vs. PB‐BEX2. † P < .05 in siControl vs. siBEX2#2. C, The BEX2 mRNA expression was also determined using real‐time PCR. The expression was normalized using ACTB. *P < .05. D, Huh‐7 cells were xenografted into NOG mice, and when the tumor was palpable, cisplatin was injected once intraperitoneally. After 7 d, mice were sacrificed and the tumors were fixed and stained using anti‐BEX2 antibody. Bar, 100 μm. E, HLE‐PB‐EV and HLE‐PB‐BEX2 cells were starved (0% FBS) for 48 h, and the quiescent population was measured using flow cytometry. F, Huh‐7‐PB‐EV and Huh‐7‐PB‐BEX2 cells were starved (0% FBS) for 48 h, and the quiescent population was measured using flow cytometry

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified BEX2 as a new dormant CSC‐related gene in HCC. Although little is known about the function of BEX2 in normal human tissues, a few reports have demonstrated its involvement in cancer: In breast cancer, transcription of BEX2 is regulated by p65/RelA and c‐Jun, and BEX2 affects the activation of RelA and c‐Jun, resulting in a decrease in the proliferation capability upon BEX2 knockdown. 13 In glioma cells, BEX2 regulates cell proliferation via the c‐Jun kinase pathway. 22 In colorectal cancer cells, BEX2 also affects cell proliferation and apoptosis. 23 The cell proliferation assay in the present study revealed that BEX2 knockdown modestly decreased the cell proliferation capability, consistent with these previous reports.

The conclusion that BEX2 is a potential marker for HCC CSCs is supported by the finding that the depletion of BEX2 attenuates CSC phenotype, sphere formation capability, tumorigenicity, cisplatin resistance, and CSC marker expression. In Huh‐7 cells, the increase in BEX2 expression was lower than in HLE cells treated with cisplatin, which could be a reason for the lack of a significant difference in cisplatin sensitivity in BEX2‐depleted Huh‐7 cells. Treatment with cisplatin increased in vivo BEX2 protein expression. As BEX2 is induced by the CMV promoter, BEX2 expression could be regulated in a post‐transcriptional manner in cisplatin‐resistant cells. We previously reported that BEX2 is degraded by the proteasomal pathway, 9 and low proteasomal activity is characteristic of CSC. 24 This suggests that cisplatin‐resistant cells have low proteasomal activity, resulting in BEX2 accumulation. BEX2 is highly expressed in dormant cells and is induced under starvation conditions, which leads to the accumulation of cells in the quiescent phase. BEX2 overexpression directly increased the quiescent population and was not localized to Ki67‐positive cells. These data suggest that BEX2 plays an important role in dormant cancer cells. There are limited reports regarding the mechanisms involved in maintaining dormant CSCs. Glycoprotein neuromedin B (NMB) decreases Ki67 levels in breast cancer cells. 25 BMP7 induces dormancy in prostate cancer stem–like cells in the bone through the activation of p38 MAPK, which induces p21 and the tumor metastasis suppressor gene NDRG1. 26 We could not elucidate the molecular mechanisms of BEX2, but our data clarified a new aspect of dormant CSC regulation in HCC.

In the current study, we analyzed the relationship between BEX2 expression and patient clinical characteristics. In multivariate analysis, BEX2 and vascular invasion were significantly correlated with relapse‐free survival among the five factors (BEX2 expression, number of tumors, T factor, vascular invasion, and stage). These data suggest that BEX2 is an independent prognostic factor and that other factors are not affected by BEX2 expression in HCC. We found that BEX2 is involved in sphere‐forming capability, although the proliferation capacity is affected little by BEX2 depletion. The sphere‐forming capability may be less sensitive to conventional pathological factors, such as tumor volume and number.

The percentage of BEX2‐expressing cancer cells is approximately 7.1%, which is a relatively low and common feature in cancer stem cells. 27 We recently reported that CD271, a CSC marker in hypopharyngeal cancer, is expressed in only 5% of the total cancer area, but anti‐CD271 antibodies exert a significant tumor suppression effect. 28 We believe that BEX2‐expressing CSCs may also be a good target for HCC therapy.

5. ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Miyagi Cancer Center (Natori, Japan) and Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical School of Medicine (Sendai, Japan). All procedures were approved by and executed in accordance with the Miyagi Cancer Center and Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical School of Medicine (permit number: 2018‐2‐052) and performed as per committee regulations. The experimental protocols of the animal experiments were approved by the Miyagi Cancer Center Animal Care and Use Committee (permit number: MCC‐AE‐2019‐8).

DISCLOSURE

There are no financial conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S2

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine. We thank Ms. Mao Nakamura‐Shima for her excellent technical assistance. This research was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers JP: 19K08430, 19K17416, 18K15799, 17K10716, 16K07132, 20K17068, and 20H03756), Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control from AMED (grant number JP17ck0106197), and Takeda Medical Foundation.

Fukushi D, Shibuya‐Takahashi R, Mochizuki M, et al. BEX2 is required for maintaining dormant cancer stem cell in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:4580–4592. 10.1111/cas.15115

REFERENCES

- 1. Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1301‐1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Cancer Observatory [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/

- 3. Wang T, Shigdar S, Gantier MP, et al. Cancer stem cell targeted therapy: progress amid controversies. Oncotarget. 2015;6(42):44191‐44206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peiris‐Pagès M, Martinez‐Outschoorn UE, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer stem cell metabolism. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, et al. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(2):153‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee TKW, Castilho A, Cheung VCH, Tang KH, Ma S, Ng IOL. CD24(+) liver tumor‐initiating cells drive self‐renewal and tumor initiation through STAT3‐mediated NANOG regulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(1):50‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kimura O, Takahashi T, Ishii N, et al. Characterization of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)+ cell population in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(10):2145‐2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haraguchi N, Ishii H, Mimori K, et al. CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3326‐3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tamai K, Nakamura‐Shima M, Shibuya‐Takahashi R, et al. BEX2 suppresses mitochondrial activity and is required for dormant cancer stem cell maintenance in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown AL, Kay GF. Bex1, a gene with increased expression in parthenogenetic embryos, is a member of a novel gene family on the mouse X chromosome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(4):611‐619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han C, Liu H, Liu J, et al. Human Bex2 interacts with LMO2 and regulates the transcriptional activity of a novel DNA‐binding complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(20):6555‐6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou X, Xu X, Meng Q, et al. Bex2 is critical for migration and invasion in malignant glioma cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2013;50(1):78‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naderi A, Liu J, Hughes‐Davies L. BEX2 has a functional interplay with c‐Jun/JNK and p65/RelA in breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ito K, Yamazaki S, Yamamoto R, et al. Gene targeting study reveals unexpected expression of brain‐expressed X‐linked 2 in endocrine and tissue stem/progenitor cells in mice. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(43):29892‐29911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mochizuki M, Tamai K, Imai T, et al. CD271 regulates the proliferation and motility of hypopharyngeal cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge‐based approach for interpreting genome‐wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545‐15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mochizuki M, Nakamura M, Sibuya R, et al. CD271 is a negative prognostic factor and essential for cell proliferation in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2019;99(9):1349‐1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sasagawa Y, Nikaido I, Hayashi T, et al. Quartz‐Seq: a highly reproducible and sensitive single‐cell RNA sequencing method, reveals non‐genetic gene‐expression heterogeneity. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. Available from: https://www.R‐project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hammil D. Interactive Analysis of Cytometry Data [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://github.com/DillonHammill/CytoExploreR

- 21. Crissman HA, Darzynkiewicz Z, Tobey RA, Steinkamp JA. Correlated measurements of DNA, RNA, and protein in individual cells by flow cytometry. Science. 1985;228(4705):1321‐1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou X, Meng Q, Xu X, et al. Bex2 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in malignant glioma cells via the c‐Jun NH2‐terminal kinase pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427(3):574‐580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu Y, Xiao Q, Chen H, et al. BEX2 promotes tumor proliferation in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13(3):286‐294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Voutsadakis IA. Proteasome expression and activity in cancer and cancer stem cells. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(3):1010428317692248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen C, Okita Y, Watanabe Y, et al. Glycoprotein nmb is exposed on the surface of dormant breast cancer cells and induces stem cell‐like properties. Cancer Res. 2018;78(22):6424‐6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kobayashi A, Okuda H, Xing F, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 in dormancy and metastasis of prostate cancer stem‐like cells in bone. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2641‐2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Magee JA, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer stem cells: impact, heterogeneity, and uncertainty. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):283‐296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morita S, Mochizuki M, Wada K, et al. Humanized anti‐CD271 monoclonal antibody exerts an anti‐tumor effect by depleting cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2019;461:144‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S2

Table S1