Abstract

Background

Statins may be protective in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 SARS-CoV-2 infection. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the effect of in-hospital statin use on 28-day mortality rates and intensive care unit (ICU) admission among patients with SARS-CoV-2, stratified into 4 groups: those who used statins before hospitalization (treatment continued or discontinued in the hospital) and those who did not (treatment newly initiated in the hospital or never initiated).

Methods

In a cohort study of 1179 patients with SARS-CoV-2, record review was used to assess demographics, laboratory measurements, comorbid conditions, and time from admission to death, ICU admission, or discharge. Using marginal structural Cox models, we estimated hazard ratios (HRs) for death and ICU admission.

Results

Among 1179 patients, 676 (57%) were male, 443 (37%) were >65 years old, and 493 (46%) had a body mass index ≥30 (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Inpatient statin use reduced the hazard of death (HR, 0.566; P=.008). This association held among patients who did and those who did not use statins before hospitalization (HR, 0.270 [P=.003] and 0.493 [P=.04], respectively). Statin use was associated with improved time to death for patients aged >65 years but not for those ≤65 years old.

Conclusion

Statin use during hospitalization for SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with reduced 28-day mortality rates. Well-designed randomized control trials are needed to better define this relationship.

Keywords: COVID-19, Statins, Mortality, Inpatient Hospitalization, marginal structural model

In a retrospective study of 1179 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, in-hospital statin use was associated with reduced 28-day mortality rates, both in patients who used statins before hospitalization and in those who did not.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the associated disease, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in millions of deaths [1]. During the initial rush for treatments, >100 off-label drugs were used to treat patients with COVID-19 [2]. Off-label statin use was considered early in the pandemic at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston, for several reasons, including reports of cardiac complications due to COVID-19 [3, 4] and the cardioprotective effect of statins [5, 6], the fact that statins are low cost and generally safe [7], and the ability of statins to blunt the hyperinflammatory response from infection [8, 9]. It was also suggested that statins block SARS-CoV-2 infectivity via binding to the main protease mediating viral entry, inhibiting the virus’s ability to invade cells [10].

The safety and efficacy of statins in the treatment of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 has remained uncertain. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of statins in acute respiratory distress syndrome and sepsis was unclear [11–13], with some trials showing no impact on mortality rates [14–16], while others found a significant improvement [17–19]. Observational studies have similarly yielded mixed results regarding the effects of statins in COVID-19. These investigations have been limited by small sample size [20–23], insufficient adjustments for time-varying confounders [20, 24, 25], and lack of a subcohort newly started on statins for COVID-19 [24, 26–28].

During the spring of 2020, physicians at MGH created clinical guidelines that recommended starting statin therapy on patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19 with preexisting primary indications [29, 30]. Clinicians were advised to continue prehospital statins and to start atorvastatin (40mg/d) in patients who had an evidence-based indication. Based on the discretion and clinical judgment of the physician, many patients, with or without preexisting cardiovascular disease, were started on statin therapy. This placed MGH in a unique position to investigate empirically the impact of starting statin therapy during hospitalization for COVID-19.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of statins on 28-day time to death in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, using robust models to account for variable timing of statin initiation and competing risks. We also aimed to evaluate the specific effect of new statin initiation on survival.

METHODS

Patient Selection

This study uses a previously described cohort of patients hospitalized at MGH [31]. Inclusion criteria included age >18 years, SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed with reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing, and hospitalization between March and June 2020. This study was approved by the local institutional review board (no. 2020P000829); a waiver of informed consent was granted.

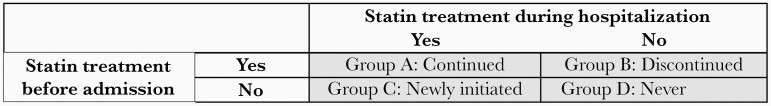

Statin Exposure

After manual record review, supplemented by medication orders automatically extracted from electronic health records, patients were categorized into 4 groups: group A, antecedent (prehospitalization) statin continued during hospitalization (“continued”); group B, antecedent statin discontinued during hospitalization (“discontinued”); group C, statin newly initiated during hospitalization (“newly initiated”); and group D, no statins used during or before hospitalization (“never”) (Figure 1). When manual record review from the patient registry [30] was in conflict with the electronic medication order data, Z. N. M. resolved any conflicts with an additional round of manual record reviews.

Figure 1.

Patients were categorized into 4 statin treatment groups: group A, antecedent (prehospitalization) statin continued during hospitalization (Continued); group B, antecedent statin discontinued during hospitalization (Discontinued); group C, statin newly initiated during hospitalization (Newly initiated); and group D, no statins used during or before hospitalization (Never).

Covariates and Outcomes

Record abstractors collected information on age, sex, smoking status, medical comorbid conditions, medications, and date of hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, death, and discharge within 28 days of presentation to care. Laboratory values, self-reported race/ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI) were extracted from the electronic health record.

The primary outcome was time to death. Patients discharged to palliative care were classified as deceased on the day of their discharge. The secondary outcome was time to ICU admission or death. For this outcome, a patient must have initiated statins during hospitalization but before ICU admission to be categorized as newly initiated or continued.

Statistical Analysis

We examined differences between baseline characteristics among the 4 statin groups, using Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test by ranks for continuous variables. Analyses that stratify patients by in-hospital statin use are subject to both immortal time bias and time-varying confounding, as a patient’s changing health condition affected when and whether statins were initiated [32]. Therefore, we used marginal structural Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the effect of statins [33]. Patients discharged alive or transferred to a nonpalliative care facility were categorized together as discharged. To fit the marginal structural Cox model, we fit a pooled multinomial regression to account for discharge as a competing risk, [34] and used inverse-probability weights that were stabilized and trimmed at the fifth and 95th percentiles. If patients did not experience the outcome and were not discharged by 28 days, they were administratively censored. We estimated the hazard ratio (HR) of each outcome for initiating statins versus not initiating statins by the previous day.

The following baseline variables were included as confounders: demographic variables (sex, age >65 years, race, active smoker, BMI >30 [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]), comorbid conditions at admission (coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic liver disease, active cancer, pulmonary disease), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use at presentation to care, number of days from 1 March 2020 to the date of hospitalization to account for era effect, and prior statin usage. The following time-varying daily laboratory measurements were included and log-transformed: absolute lymphocyte count, white blood cell count, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), C-reactive protein, creatine kinase (CK), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. To account for missing data, we used multiple imputation with 25 imputations. Peak laboratory values were calculated for each statin group, defined as the highest laboratory measurement observed between hospital admission to the end of follow-up.

For the primary outcome of death, we also adjusted for ICU admission status each day as a time-varying confounder; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values were calculated, accounting for the uncertainty due to estimation of the weighting models [34], and results across imputations were combined using Rubin’s rules [35].

The analysis was repeated for the primary and secondary outcomes in the subsets of patients who were not prior users (newly initiated [group C] vs never [group D]) and those who were prior users (continued [group A] vs discontinued [group B]). In total, 6 models were fit. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.2 [36]. The nnet package [37] was used to fit the multinomial regression model and the jomo package [38] was used to perform multiple imputation. A Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to control the false discovery rate [39].

Sensitivity Analyses

An additional analysis was performed using E-values to assess robustness of the observed results to unmeasured confounding. The E-value assesses how strong an unmeasured confounder would have to be to fully explain away the observed results [40]. We also assessed whether the effect of statins differed between patients >65 versus ≤65 years of age. First, we fit the marginal structural models, including an interaction term between statin initiation and whether a patient was >65 years old, and then we repeated the analysis, stratifying by whether patients were aged >65 years. Finally, we assessed whether exclusion of patients who were admitted to the ICU on the same day of their hospital admission affected the relationship between statin initiation and the primary outcome of death.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Overall, 1179 adult patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 were included, after the exclusion of 7 patients who were deceased, discharged, or censored on the day of their hospital admission (Supplementary Table 1). Of these patients, 676 (57%) were male, 443 (38%) were >65 years old, and 493 (46%) had a BMI ≥30. Patient characteristics differed by statin group (Table 1). Patients on statins before hospitalization (groups A and B) were older (median age, 69 vs 52 years) and had higher rates of coronary artery disease (29% vs 3%), congestive heart failure (19% vs 5%), hypertension (74% vs 34%), type 2 diabetes (56% vs. 17%), and dyslipidemia (67% vs 16%) than those not on statins before hospitalization (groups C and D) (all differences, P<.001). White/non-Hispanics were more likely to be on statins before hospitalization than Hispanics (56% vs 33%, respectively; P<.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized for Coronavirus Disease 2019, Stratified by Statin Treatment Group (N = 1179)

| Characteristic | Patients, No. With Characteristic/No. in Statin Treatment Group (%)a | P Valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: Continued (n=466) | Group B: Discontinued (n=42) | Group C: Newly Initiated (n=311) | Group D: Never (n=360) | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Male sex | 298/466 (63.9) | 26/42(61.9) | 173/311 (55.6) | 179/360 (49.7) | .001 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 68 (59–78) [n=466] | 70 (58–78) [n=42] | 55 (43–66) [n=311] | 48 (35–62) [n=360] | <.001 |

| Age >65 y | 265/466 (56.9) | 24/42 (57.1) | 83/311 (26.7) | 71/360 (19.7) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 233/457 (51) | 23/42 (54.8) | 84/301 (27.9) | 114/355 (32.1) | <.001 |

| Black or African American | 40/457 (8.8) | 7/42 (16.7) | 43/301 (14.3) | 37/355 (10.4) | |

| Hispanic | 131/457 (28.7) | 10/42 (23.8) | 129/301 (42.9) | 159/355 (44.8) | |

| Other (American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, others) | 53/457 (11.6) | 2/42 (4.8) | 45/301 (15) | 45/355 (12.7) | |

| Active smoker | 24/442 (5.4) | 7/37 (18.9) | 15/275 (5.5) | 39/330 (11.8) | <.001 |

| BMI,c median (IQR) | 29 (26–34) [n=430] | 29 (25–32) [n=38] | 30 (26–34) [n=290] | 29 (25–34) [n=316] | .74 |

| BMI ≥30c | 192/430 (44.7) | 14/38 (36.8) | 141/290 (48.6) | 146/316 (46.2) | .50 |

| Comorbid conditions at admission | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 140/466 (30) | 6/42 (14.3) | 9/311 (2.9) | 12/360 (3.3) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 90/466 (19.3) | 6/42 (14.3) | 15/311 (4.8) | 19/360 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 349/466 (74.9) | 29/42 (69) | 130/311 (41.8) | 100/360 (27.8) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 261/466 (56) | 24/42 (57.1) | 76/311 (24.4) | 42/360 (11.7) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 320/466 (68.7) | 19/42 (45.2) | 59/311 (19) | 46/360 (12.8) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 121/458 (26.4) | 9/41 (22) | 31/299 (10.4) | 32/356 (9) | <.001 |

| Dialysis | 18/458 (3.9) | 1/41 (2.4) | 7/299 (2.3) | 6/356 (1.7) | .24 |

| Chronic liver diseased | 37/458 (8.1) | 5/41 (12.2) | 30/299 (10) | 36/353 (10.2) | .57 |

| Alcohol-related cirrhosis | 4/458 (0.9) | 2/41 (4.9) | 5/299 (1.7) | 4/353 (1.1) | .16 |

| NAFLD | 22/458 (4.8) | 0/41 (0) | 16/299 (5.4) | 14/353 (4) | .50 |

| Current viral hepatitis | 18/466 (3.9) | 1/42 (2.4) | 11/311 (3.5) | 25/360 (6.9) | .12 |

| HIV | 6/413 (1.5) | 0/40 (0) | 4/283 (1.4) | 6/329 (1.8) | .95 |

| History of cancer | 88/459 (19.2) | 10/42 (23.8) | 43/298 (14.4) | 32/354 (9) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 167/461 (36.2) | 14/41 (34.1) | 76/301 (25.2) | 91/357 (25.5) | .001 |

| COPD | 71/461 (15.4) | 6/41 (14.6) | 20/301 (6.6) | 23/357 (6.4) | <.001 |

| Asthma | 60/461 (13) | 7/41 (17.1) | 37/301 (12.3) | 55/357 (15.4) | .55 |

| ILD | 3/461 (0.7) | 0/41 (0) | 3/301 (1) | 3/357 (0.8) | .94 |

| Home oxygen supplementation | 14/461 (3) | 1/41 (2.4) | 3/301 (1) | 3/357 (0.8) | .06 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 46/466 (9.9) | 4/42 (9.5) | 16/311 (5.1) | 12/360 (3.3) | .001 |

| History of organ transplantation | 13/462 (2.8) | 2/41 (4.9) | 6/301 (2) | 7/356 (2) | .48 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment in past 6 mo | 36/448 (8) | 4/38 (10.5) | 16/295 (5.4) | 22/353 (6.2) | .37 |

| Type and dose of statin at presentation to care | |||||

| Atorvastatin (any) | 309/458 (67.5) | 28/41 (68.3) | … | … | .36 |

| Atorvastatin (10–20mg/d) | 95/309 (30.7) | 7/28 (25) | … | … | |

| Atorvastatin (40–60mg/d) | 116/309 (37.5) | 12/28 (42.9) | … | … | |

| Atorvastatin (80mg/d) | 85/309 (27.5) | 7/28 (25) | … | … | |

| Atorvastatin (unknown dosage) | 13/309 (4.2) | 2/28 (7.1) | … | … | |

| Rosuvastatin | 39/458 (8.5) | 1/41 (2.4) | … | … | |

| Other statins | 110/458 (24) | 12/41 (29.3) | … | … | |

| Type and dose of statin during hospitalization | |||||

| Atorvastatin | 331/434 (76.3) | … | 274/285 (96.1) | … | <.001 |

| Atorvastatin (10–20mg/d) | 76/331 (23) | … | 53/274 (19.3) | … | |

| Atorvastatin (40–60mg/d) | 138/331 (41.7) | … | 147/274 (53.6) | … | |

| Atorvastatin (80mg/d) | 117/331 (35.3) | … | 74/274 (27) | … | |

| Atorvastatin (unknown dosage) | 0/331 (0) | … | 0/274 (0) | … | |

| Rosuvastatin | 33/434 (7.6) | … | 6/285 (2.1) | … | |

| Other statins | 70/434 (16.1) | … | 5/285 (1.8) | … | |

| Duration of preadmission statin use at presentation to care | |||||

| ≤1 y | 54/466 (11.6) | 4/42 (9.5) | … | … | .97 |

| >1 y | 244/466 (52.4) | 23/42 (54.8) | … | … | |

| Unknown | 168/466 (36.1) | 15/42 (35.7) | … | … | |

| ACE inhibitor | 116/466 (24.9) | 4/42 (9.5) | 30/311 (9.6) | 33/360 (9.2) | <.001 |

| Azithromycin | 17/457 (3.7) | 2/42 (4.8) | 18/302 (6) | 22/353 (6.2) | .33 |

| Immunosuppressants | 42/466 (9) | 3/42 (7.1) | 20/311 (6.4) | 22/360 (6.1) | .40 |

| Oral steroid | 29/466 (6.2) | 3/42 (7.1) | 13/311 (4.2) | 17/360 (4.7) | .51 |

| Immunomodulators | 13/466 (2.8) | 2/42 (4.8) | 10/311 (3.2) | 8/360 (2.2) | .60 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 4/466 (0.9) | 0/42 (0) | 3/311 (1) | 3/360 (0.8) | >.99 |

| Symptomatic at presentation to care | 439/462 (95) | 36/40 (90) | 305/309 (98.7) | 333/357 (93.3) | .001 |

| First available laboratory values, median (IQR)e | |||||

| WBC count, cells/µL | 6.5 (4.9–8.3) [n=466] | 7.1 (5.2–10.5) [n=40] | 6.8 (5.2–9.2) [n=311] | 6.7 (4.9–9.2) [n=349] | .15 |

| AST, U/L | 40 (28–56) [n=463] | 58 (30–121) [n=38] | 44 (31–65) [n=311] | 48 (30–72) [n=338] | <.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 27 (18–42) [n=463] | 34 (23–62) [n=38] | 34 (21–58) [n=311] | 34 (21–66) [n=338] | <.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) [n=463] | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) [n=38] | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) [n=311] | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) [n=339] | .12 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 86 (67–108) [n=463] | 91 (69–127) [n=38] | 75 (59–95) [n=311] | 80 (62–108) [n=338] | <.001 |

| Troponin, ng/L | 17 (8–39) [n=451] | 39 (14–90) [n=38] | 8 (6–17) [n=305] | 7 (6–18) [n=322] | <.001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 74 (33–142) [n=459] | 85 (48–152) [n=36] | 89 (49–152) [n=311] | 68 (31–136) [n=330] | .001 |

| ESR, mm/h | 41 (27–63) [n=426] | 49 (35–84) [n=32] | 42 (28–65) [n=297] | 35 (21–54) [n=295] | <.001 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 114 (63–217) [n=461] | 298 (82–702) [n=36] | 114 (67–223) [n=310] | 132 (65–349) [n=331] | .003 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 1063 (695–1812) [n=455] | 1554 (826–6580) [n=37] | 1074 (693–1770) [n=305] | 949 (608–1661) [n=329] | .002 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×103 cells/µL | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) [n=466] | 1 (0.6–1.5) [n=40] | 1 (0.7–1.3) [n=311] | 1 (0.7–1.4) [n=341] | .13 |

| Time from 1 March 2020 to hospital admission date, median (IQR), d | 43 (33–52) [n=466] | 50 (41–56) [n=42] | 37 (30–44) [n=311] | 46 (40–54) [n=360] | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IQR, interquartile range; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; WBC, white blood cell.

Data represent no. with characteristic/no. in statin treatment group (%), unless otherwise specified. Treatment groups were defined as follows: group A, antecedent (prehospitalization) statin continued during hospitalization (Continued); group B, antecedent statin discontinued during hospitalization (Discontinued); group C, statin newly initiated during hospitalization (Newly Initiated); and group D, no statins used during or before hospitalization (Never).

P values were calculated comparing all 4 groups, using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

BMI calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Unknown and other chronic liver disease are not presented in this table.

This is the first available laboratory result after admission.

In total, 777 patients (66%) received a statin during their hospitalization for COVID-19. Of these, 274 of 285 patients (96%) with statins newly initiated and 331 of 434 (76%) continued on statins were prescribed atorvastatin; the most common atorvastatin dosage was 40mg/d. Among those continued on statins, the majority were prescribed statins for >1 year before hospitalization (244 of 466 [52%]). Supplementary Table 2 contains information on when statins were initiated during hospitalization relative to admission date. According to the first laboratory measurements obtained during hospitalization, patients who discontinued statins at hospitalization had higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates (P=.046), CK (P=.001), troponin levels (P<.001), and D-dimer levels (P=.002), compared with the other cohorts (Table 1).

Unadjusted Analysis

In this cohort, 154 patients (13%) died and 841 (71%) were discharged within 28 days. In unadjusted analyses, patients on statins during hospitalization had similar rates of death as those not on statins during hospitalization (108 [14%] vs 46 [11%], respectively; P=.27), but higher rates of ongoing hospitalization at 28 days (144 [19%] vs 40 [10%]; P<.001) and ICU admission (276 [36%] vs 85 [21%]; P<.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Patient Outcomes at 28 Days After Presentation to Care by Statin Treatment Group (N = 1179)

| Outcome | Patients, No. With Characteristic/No. in Statin Treatment Group (%)a | P Valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: Continued (n=466) | Group B: Discontinued (n=42) | Group C: Newly Initiated (n=311) | Group D: Never (n=360) | ||

| Patient status at 28 d | |||||

| Deceasedc | 78/466 (16.7) | 14/42 (33.3) | 30/311 (9.6) | 32/360 (8.9) | <.001 |

| Discharged alive | 252/466 (54.1) | 20/42 (47.6) | 176/311 (56.6) | 257/360 (71.4) | <.001 |

| Transfer to other facility (nonpalliative care) | 61/466 (13.1) | 4/42 (9.5) | 36/311 (11.6) | 35/360 (9.7) | <.001 |

| Still hospitalized at 28 d | 75/466 (16.1) | 4/42 (9.5) | 69/311 (22.2) | 36/360 (10.0) | <.001 |

| Time from hospital admission to death, median (IQR), d | 10 (6–15) [n=78] | 3 (1–4) [n=14] | 12 (7–16) [n=30] | 6 (3–13) [n=32] | <.001 |

| Time from hospital admission to discharge or transfer, median (IQR), d | 7 (4–10) [n=313] | 4 (1–6) [n=24] | 7 (4–10) [n=212] | 5 (3–8) [n=292] | <.001 |

| Patient events during 28-d follow-up | |||||

| ICU admission | 145/466 (31.1) | 8/42 (19.0) | 131/311 (42.1) | 77/360 (21.4) | <.001 |

| Invasive intubation | 122/466 (26.2) | 6/42 (14.3) | 110/311 (35.4) | 65/360 (18.1) | <.001 |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 132/466 (28.3) | 9/42 (21.4) | 106/311 (34.1) | 71/360 (19.7) | <.001 |

| ARDS | 112/466 (24.0) | 5/42 (11.9) | 105/311 (33.8) | 61/360 (16.9) | <.001 |

| Stroke/CVA | 3/466 (0.6) | 1/42 (2.4) | 3/311 (1.0) | 2/360 (0.6) | .39 |

| Cardiac arrest | 2/466 (0.4) | 1/42 (2.4) | 2/311 (0.6) | 2/360 (0.6) | .39 |

| Rhabdomyolysis/myositis | 18/466 (3.9) | 2/42 (4.8) | 18/311 (5.8) | 21/360 (5.8) | .50 |

| Liver dysfunction | 80/466 (17.2) | 11/42 (26.2) | 71/311 (22.8) | 64/360 (17.8) | .12 |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Data represent no. with characteristic/no. in statin treatment group (%), unless otherwise specified. Treatment groups were defined as follows: group A, antecedent (prehospitalization) statin continued during hospitalization (Continued); group B, antecedent statin discontinued during hospitalization (Discontinued); group C, statin newly initiated during hospitalization (Newly Initiated); and group D, no statins used during or before hospitalization (Never).

P values were calculated comparing all 4 groups, using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Deceased patients include 3 who were discharged to hospice care.

Peak Laboratory Values

Unadjusted peak values for liver biochemistry and inflammatory markers differed across statin groups (Table 3), with the highest peaks of AST and ALT in the newly initiated statin group. Patients with newly initiated statins had a lower peak CK than those who discontinued statins (median [interquartile range (IQR)], 222 [90–636] vs 374 [89–838] U/L, respectively) but higher peak CK than those who continued statins (178 [85–507] U/L) or who never used statins (173 [78–578] U/L).

Table 3.

Unadjusted Peak Laboratory Values by Statin Treatment Group (N = 1179)

| Laboratory Value | Peak Value by Statin Treatment Group, Median (IQR)a | P Valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: Continued (n=466) | Group B: Discontinued (n=42) | Group C: Newly Initiated (n=311) | Group D: Never (n=360) | ||

| WBC count, cells/µL | 8.7 (6.6–12.5) [n=466] | 7.9 (6.3–16) [n=40] | 9.9 (7.1–15.2) [n=311] | 8.3 (6.2–12.1) [n=349] | .001 |

| AST, U/L | 65 (40–119) [n=463] | 60 (32–208) [n=38] | 84 (45–150) [n=311] | 66 (35–127) [n=338] | .008 |

| ALT, U/L | 46 (26–85) [n=463] | 47 (23–121) [n=38] | 68 (31–120) [n=311] | 57 (26–118) [n=338] | <.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) [n=463] | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) [n=38] | 0.6 (0.5–1) [n=311] | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) [n=339] | .01 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 105 (79–166) [n=463] | 101 (77–155) [n=38] | 97 (72–156) [n=311] | 96 (72–140) [n=338] | .02 |

| Troponin, ng/L | 23 (10–52) [n=451] | 40 (14–90) [n=38] | 12 (6–29) [n=305] | 8 (6–23) [n=322] | <.001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 145 (69–252) [n=459] | 141 (50–231) [n=36] | 151 (82–283) [n=311] | 117 (52–175) [n=330] | <.001 |

| ESR, mm/h | 57 (36–104) [n=426] | 68 (36–90) [n=32] | 72 (41–114) [n=297] | 44 (26–74) [n=295] | <.001 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 178 (85–507) [n=461] | 374 (89–838) [n=36] | 222 (90–636) [n=310] | 173 (78–578) [n=331] | .03 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 1863 (986–3596) [n=455] | 1944 (1075–7380) [n=37] | 2090 (1038–5098) [n=305] | 1241 (713–3270) [n=329] | <.001 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×103 cells/µL | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) [n=466] | 1.5 (1–2.5) [n=40] | 1.9 (1.4–2.4) [n=311] | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) [n=341] | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IQR, interquartile range; WBC, white blood cell.

Statin treatment groups were defined as follows: group A, antecedent (prehospitalization) statin continued during hospitalization (Continued); group B, antecedent statin discontinued during hospitalization (Discontinued); group C, statin newly initiated during hospitalization (Newly Initiated); and group D, no statins used during or before hospitalization (Never).

P values were calculated comparing all 4 groups, using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Primary Outcome Analysis

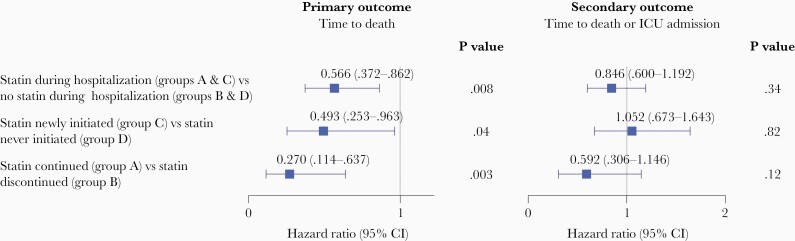

The median time to death in each statin group can be found in Table 2. Overall, statin usage during hospitalization decreased the hazard of death (HR, 0.566 [95% CI, .372–.862]; P=.008). In the subgroup of patients not using statin therapy before hospitalization, new statin initiation at hospitalization decreased the hazard of death (HR, 0.493 [95% CI, .253–.963]; P=.04). Of the subgroup of patients who were using statin therapy before hospitalization, continued statin usage also decreased the hazard of death (HR, 0.270 [95% CI, .114–.637]; P=.003) (Figure 2). A summary of the distribution of missing laboratory measurements can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 2.

Marginal structural model outputs for primary and secondary outcomes. Estimates were obtained from fitting marginal structural Cox models adjusted for the following baseline covariates: sex, age >65 years, race, active smoker, body mass index ≥30 (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), comorbid conditions on admission (coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic liver disease, active cancer, pulmonary disease), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, number of days since 1 March 2020, and prior statin usage. The following time–varying covariates were also adjusted for: absolute lymphocyte count, white blood cell count, aspartate aminotransferase, C-reactive protein, creatine kinase, alanine aminotransferase, and intensive care unit (ICU) admission status. Models were fit accounting for immortal time bias, time–varying confounding, and discharge as a competing risk. Applying a Benjamini-Hochberg correction to the primary outcome analysis, the 3 calculated P values all fall below the corrected significance thresholds: .003<.017, .008<.033, and .038<.05. Hazard ratios are given with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Secondary Outcome Analysis

A total of 198 patients were excluded from secondary outcome analyses because they were admitted to the ICU on the day of hospitalization (Supplementary Table 1). Of the 981 patients remaining, 588 (60%) used statins during their hospitalization. Statin use during hospitalization did not change the hazard of the composite outcome of death or ICU admission (HR, 0.846 [95% CI, .600–1.192]; P=.34) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4).

Sensitivity Analyses

For the primary outcome assessing mortality, the point estimate and the upper confidence limit of the E-value associated with statin use during hospitalization are 2.326 and 1.455, respectively. Given that the E-value of 2.326 is much greater than any observed known risk factors examined in the current study (with the exception of age), it is unlikely that an unmeasured confounder could explain away the observed effect in the present analysis. The point estimate and the upper confidence limit of the E-value associated with new initiation of statins are 2.639 and 1.191, respectively. For continuation of statins, these values are 4.305 and 2.073, respectively.

When an interaction term between statin use and age >65 years old was included in the model, the interaction term was observed to be statistically significant for the primary outcome when including all participants (HR, 0.293; P=.009) and when comparing the “newly initiated” and “never” statin groups (HR, 0.194; P=.008), which indicated that statins were more protective among patients >65 years of age (Supplementary Table 5). When analyses were repeated stratifying by patient age (≤65 vs >65 years), statin use during hospitalization did not change the hazard of death in patients ≤65 years old (n=736; HR, 1.175 [95% CI, .520–2.655]; P=.70) (Supplementary Table 6); however, patients >65 years old were found to have a decreased hazard of death with any statin use during hospitalization (n=443; HR, 0.477 [95% CI, .292–.78]; P=.003) and within the subgroup of patients with statins newly initiated during hospitalization (HR, 0.321 [95% CI, .137–.752]; P=.009) (Supplementary Table 7). When patients who were admitted to the ICU on the day of hospital admission were excluded from analyses of the primary outcome, the protective effect of statins was preserved, whether or not analyses were restricted to patients with statin usage before hospitalization (Supplementary Table 8).

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort from a single tertiary medical center, we found that statin use during hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with reduced short-term mortality rates. The survival benefit was seen in both patients who continued statin therapy and those with statins newly initiated during hospitalization. In sensitivity analyses, statin use was associated with reduced mortality rates for patients aged >65 years but not for those ≤65 years old. The protective effect of statins in preventing death was preserved even when patients who were admitted immediately to the ICU were excluded from the analysis.

Our study confirms and expands on prior work. A recent propensity score–matched analysis found that statin use before hospitalization reduces the short-term in-hospital mortality risk from COVID-19 [27]. This study probed further, into whether in-hospital statin use had a similar effect on mortality risk. To investigate the impact of statins administered during hospitalization, we used marginal structural models, which account for both survivorship bias (ie, patients need to survive long enough to begin statins) and time-varying confounding bias (ie, patient health status during hospitalization changes over time, affecting the likelihood of initiating treatment). Our study accounted for a wide variety of time-varying confounders, which we believe accurately captures temporal shifts in the likelihood of initiating treatment. We further expanded on prior literature by specifically evaluating the effect of statin initiation during hospitalization without prior use, because 26% of our cohort had statins newly initiated during hospitalization for COVID-19. Overall, the novel findings presented here are that statin therapy during hospitalization, whether new or continued, was associated with reduced mortality rates.

The composition of our cohort was similar to those of other published patient databases of patients with COVID-19 [21, 26, 28]. The median patient age (IQR) was 60 (47–73) years. Obese patients with a BMI ≥30 represented almost half the population (46%), similar to rates in prior studies [21, 26, 41] and consistent with evidence that obesity is a risk factor for hospitalization with COVID-19 [42]. Racial and ethnic demographics vary immensely across the literature. However, it is important to note that nationwide, large observational studies have illustrated that underserved communities and people of color are more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 [43]. The current study reinforces these findings, with the majority of patients identifying with a race or ethnicity other than white (61%), with Hispanic patients (36.4%) the most common, followed by Asian and Native American patients (13%) and black/non-Hispanic patients (10.8%). The mortality rate in this cohort (13.1%) was similar to the mean published United States hospital mortality rates for patients admitted with COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic (11.8%) among 955 hospitals [44].

Our findings contradict some prior reports. One meta-analysis of 3449 patients in 9 observational studies found that statin use did not improve rates of severe outcomes or death in COVID-19 [45]. The majority of these studies were small (as few as 50 patients) and most failed to control for potential confounders. Comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, are established risk factors for more severe COVID-19 disease, and patients prescribed statins are more likely to have these comorbid conditions, highlighting the critical need to control for confounding in this analysis [22]. In addition, most prior work examined the relationship either with antecedent statin usage before hospitalization [23, 25–28] or only with statin use during hospitalization [20, 22, 24]. Our study had several advantages: we investigated the influence of statin use both before and during hospitalization, minimized immortal time bias, adjusted for time-varying confounders, and minimized era effect (or the potential changes in COVID-19 care over time). These advantages provide clarity not offered by previous studies.

The duration of statin therapy required to provide mortality benefit in COVID-19 remains unclear. Our findings suggest that statins do not cause harm and may be associated with a survival benefit after even brief exposure during hospitalization. The reduced hazard of death associated with statin usage was greatest in patients continued on statin therapy, suggesting that the benefit seen with statin exposure may be greater with longer exposure to statins before illness. It is important to note that while patients with newly initiated statins were found to have an associated mortality benefit, this cohort was also found to have higher levels of ICU admission than patients with continuation of antecedent statin usage.

As Table 1 illustrates, patients with newly initiated statins were found to have higher levels of inflammatory markers than those with antecedent statin usage, with the following median (IQR) values: C-reactive protein (85 [48–152] mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (49 [35–84] mm/h), and D-dimer (1554 [826–6580] ng/mL). While our data do not prove this, it is theoretically possible that statin usage before viral infection may blunt the inflammatory response caused by both the virus and the immune system. For instance, in a prior phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial investigating the impact of atorvastatin on severe sepsis, the investigators found that prior statin use decreased interleukin 6 levels and reduced the mortality rate; however, this was not seen in statin-naive patients with in-hospital statin exposure only [11]. Further insight is needed on a possible dose and duration effect.

Interestingly, a Cochrane systematic review assessing the effects of early administered statins in patients with acute coronary syndrome found no significantly reduced risk of death, nonfatal myocardial ischemia, or stroke at 1 month [46]. Further study is needed on statins’ main therapeutic mechanism of action in patients with SARS-COV-2 infection and how this may differ from the benefits seen in cardiovascular disease. Given the association between COVID-19 infection and a hyperinflammatory response that provokes end-organ damage [6], new initiation of statins for even a short duration may have had a positive effect on both mortality rate and secondary complications.

Another proposed explanation for statins’ mechanism of action in COVID-19 is their ability to inhibit hydroxymethylglutaryl–coenzyme A reductase, which may interfere with the invasion of the virus into cells by compromising the lipid-rich membrane required for SARS-CoV-2 to interact with the cellular receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 [47]. If statins improve COVID-19 outcomes by inhibiting viral cell invasion, the benefit may be enhanced when statins are prescribed before infection.

In the current study, we found an association with mortality benefit with statin use in adults >65 years old but not in those aged ≤65 years. Given that these findings were generated from a sensitivity analysis, we hesitate to provide age cutoffs for statin initiation in the treatment of COVID-19, but we do not believe that age should be a contraindication to statin use during COVID-19 hospitalization.

Liver biochemistry values are frequently elevated in severe COVID-19 disease and are associated with worse clinical outcomes [48]. Separately, statins are known to increase liver biochemistries in certain patients [42]. In the current study, newly initiated statin use was associated with higher peak levels of AST and ALT throughout hospitalization; however, only 16% of patients receiving statins had an ALT level > 5 times the upper limit of normal, a similar rate compared with other cohorts with severe COVID-19 [49]. These findings are limited, in that peak levels could have occurred before or after statin initiation and were unadjusted for confounding. Despite these limitations, there is no clear evidence that statin exposure during infection is associated with clinically important hepatotoxicity.

Myotoxicity is a known, albeit rare, complication of statins. In the context of COVID-19, in which elevated CK levels are prevalent, there is concern that statins could increase myotoxicity and subsequent CK-induced nephrotoxicity. This was not seen among individuals with newly initiated or continued statin therapy, with CK peak levels never reaching 3 times the upper limit of normal, considered the threshold for acute kidney injury due to pigment-associated nephropathy [50].

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of study design. Although we used 2 data sources to confirm demographics, medications, laboratory data, and clinical outcomes, misclassification errors are possible. We limited this error rate by using physician review of discrepant data. In addition, we were unable to account for patients who had dose escalations in their statin usage or who had their statin temporarily held during hospitalization. Finally, patients who were on statin therapy before hospitalization but had the statin discontinued during hospitalization, presumably owing to organ dysfunction, are a unique subcohort of patients that warrant further exploration, and there may be additional unmeasured time-varying factors that explain their poorer outcomes. Given the safety and availability of statins worldwide, a randomized controlled trial of statins in COVID-19 should be considered.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the Massachusetts General Hospital Division of Clinical Research. Funding was used primarily to support the Massachusetts General Hospital coronavirus disease 2019 registry development and statistical analysis.

Potential conflicts of interest. J. J. L. is funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant ES007142). A. S. F. receives funding through the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant R01 GM127862). R. T. C. received research grants from AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, Boehringer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Roche, GSK, Synlogic, and Kaleido and receives funding through the MGH Research Scholars program. P. P. B. consults for Synlogic and is supported by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Transplant Hepatology Award and the American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award (though neither supported this work). All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented at: The Massachusetts General Hospital, Department of Medicine Ground Rounds by the first author ZM (Titled: Association of Statins and 28-Day Mortality Rates in Patients Hospitalized With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection) on 13 May 2021.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. United States COVID-19 cases and deaths by state. US Department of Health and Human Services, 2020. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days. Accessed October 11, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fajgenbaum DC, Khor JS, Gorzewski A, et al. Treatments administered to the first 9152 reported cases of COVID-19: a systematic review. Infect Dis Ther 2020; 9:435–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020; 141:1648–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fried JA, Ramasubbu K, Bhatt R, et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation 2020; 141:1930–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5:802–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76:533–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the medical expenditure panel survey. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sapey E, Patel JM, Greenwood H, et al. Simvastatin improves neutrophil function and clinical outcomes in pneumonia. a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200:1282–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parihar SP, Guler R, Brombacher F.. Statins: a viable candidate for host-directed therapy against infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2019; 19:104–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reiner Ž, Hatamipour M, Banach M, et al. Statins and the COVID-19 main protease: in silico evidence on direct interaction. Arch Med Sci 2020; 16:490–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kruger P, Bailey M, Bellomo R, et al. ; ANZ-STATInS Investigators–ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. A multicenter randomized trial of atorvastatin therapy in intensive care patients with severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187:743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kopterides P, Falagas ME.. Statins for sepsis: a critical and updated review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15:325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chalmers JD, Short PM, Mandal P, Akram AR, Hill AT.. Statins in community acquired pneumonia: evidence from experimental and clinical studies. Respir Med 2010; 104:1081–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Truwit JD, Bernard GR, Steingrub J, et al. Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McAuley DF, Laffey JG, O’Kane CM, et al. ; HARP-2 Investigators; Irish Critical Care Trials Group. Simvastatin in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Rothberg MB.. Statin therapy and mortality from sepsis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med 2015; 128:410–7.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frost FJ, Petersen H, Tollestrup K, Skipper B.. Influenza and COPD mortality protection as pleiotropic, dose-dependent effects of statins. Chest 2007; 131:1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vandermeer ML, Thomas AR, Kamimoto L, et al. Association between use of statins and mortality among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections: a multistate study. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel JM, Snaith C, Thickett DR, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 40mg/day of atorvastatin in reducing the severity of sepsis in ward patients (ASEPSIS Trial). Crit Care 2012; 16:R231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodriguez-Nava G, Trelles-Garcia DP, Yanez-Bello MA, Chung CW, Trelles-Garcia VP, Friedman HJ.. Atorvastatin associated with decreased hazard for death in COVID-19 patients admitted to an ICU: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care 2020; 24:429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Song SL, Hays SB, Panton CE, et al. Statin use is associated with decreased risk of invasive mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 patients: a preliminary study. Pathogens 2020; 9:759. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9090759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tan WYT, Young BE, Lye DC, Chew DEK, Dalan R.. Statin use is associated with lower disease severity in COVID-19 infection. Sci Rep 2020; 10:17458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Spiegeleer A, Bronselaer A, Teo JT, et al. The effects of ARBs, ACEis, and statins on clinical outcomes of COVID-19 infection among nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21:909–14.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang XJ, Qin JJ, Cheng X, et al. In-hospital use of statins is associated with a reduced risk of mortality among individuals with COVID-19. Cell Metab 2020; 32:176–87.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan H, Valdes AM, Vijay A, et al. Role of drugs used for chronic disease management on susceptibility and severity of COVID-19: a large case-control study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020; 108:1185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daniels LB, Sitapati AM, Zhang J, et al. Relation of statin use prior to admission to severity and recovery among COVID-19 inpatients. Am J Cardiol 2020; 136:149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Poterucha TJ, et al. Association between antecedent statin use and decreased mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nat Commun 2021; 12:1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Butt JH, Gerds TA, Schou M, et al. Association between statin use and outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e044421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Massachusetts General Hospital. Rationale for consideration of statins for COVID-19 patients: the General Hospital Corporation. 2020. https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/MGH/pdf/news/coronavirus/rationale-for-consideration-of-statins-for-COVID-19-patient.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2021.

- 30. McCarthy CP, Murphy S, Jones-O’Connor M, et al. Early clinical and sociodemographic experience with patients hospitalized with COVID-19 at a large American healthcare system. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 26:100504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bassett IV, Triant VA, Bunda BA, et al. Massachusetts general hospital Covid-19 registry reveals two distinct populations of hospitalized patients by race and ethnicity. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0244270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolkewitz M, Lambert J, von Cube M, et al. Statistical analysis of clinical COVID-19 data: a concise overview of lessons learned, common errors and how to avoid them. Clin Epidemiol 2020; 12:925–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hernán MA, Brumback B, Robins JM.. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology 2000; 11:561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moodie EE, Stephens DA, Klein MB.. A marginal structural model for multiple-outcome survival data: assessing the impact of injection drug use on several causes of death in the Canadian Co-infection Cohort. Stat Med 2014; 33:1409–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Little RJ, Tchetgen EJT, Troxel AB.. University of Pennsylvania 11th annual conference on statistical issues in clinical trials: estimands, missing data and sensitivity analysis (afternoon panel session). Clin Trials 2019; 16:381–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Venables W, Ripley BD.. Modern applied statistics with S. 4th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quartagno M, Grund S, Carpenter J.. Jomo: a flexible package for two-level joint modelling multiple imputation. R Journal 2019; 9.1. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2019/RJ-2019-034/RJ-2019-034.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y.. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B 1995; 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ding P, VanderWeele TJ.. Sensitivity analysis without assumptions. Epidemiology 2016; 27:368–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020; 369:m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fresán U, Guevara M, Elía F, Albéniz E, Burgui C, Castilla J; Working Group for the Study of COVID-19 in Navarra. Independent role of severe obesity as a risk factor for COVID-19 hospitalization: a Spanish population-based cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021; 29:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML.. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:703–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Asch DA, Sheils NE, Islam MN, et al. Variation in US hospital mortality rates for patients admitted with COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181:471–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A.. Statin therapy did not improve the in-hospital outcome of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020; 14:1613–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vale N, Nordmann AJ, Schwartz GG, et al. Statins for acute coronary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 6:CD006870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu Y, Liu DX, Tam JP.. Lipid rafts are involved in SARS-CoV entry into Vero E6 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008; 369:344–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mishra K, Naffouj S, Gorgis S, et al. Liver injury as a surrogate for inflammation and predictor of outcomes in COVID-19. Hepatol Commun 2021; 5:24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fan Z, Chen L, Li J, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19-related liver damage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020. ; 5:1561–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sakthirajan R, Dhanapriya J, Varghese A, et al. Clinical profile and outcome of pigment-induced nephropathy. Clin Kidney J 2018; 11:348–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.