Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitality organizations are trying to help their employees overcome various challenges. Career adaptability has proven to be useful in helping employees handle challenges, while proactive personality is a critical factor affecting the formation of career adaptability. However, career adaptability can be a double-edged sword, and it is unclear how it may impact employees’ turnover intentions. Drawing on social exchange theory, the current study reconciles mixed findings in the literature by proposing a moderated mediation model suggesting that work social support moderates the indirect relationship between proactive personality and turnover intentions through career adaptability. Results based on data collected from 339 hotel employees in the United States indicate that proactive personality is positively associated with employees’ career adaptability. More importantly, work social support significantly moderates the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. Theoretical and managerial implications are discussed.

Keywords: Career adaptability, Work social support, Supervisor support, Coworker support, Social exchange theory, Proactive personality, Turnover intentions, COVID-19 pandemic

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected many industries since the beginning of 2020 due to limited human mobility and travel restrictions imposed by many countries (World Health Organization (WHO, 2020). As a result, the tourism and hospitality industry has experienced an immediate negative impact during the pandemic, and many tourist attractions and hotels have shut down because domestic and international travel has been suspended (Baum & Hai, 2020). The American Hotel and Lodging Association (2020) projected this year (i.e., 2020) to be the worst on record for the hotel industry, with negative repercussions for labor demand. Hotel owners are being forced to consider or even implement layoffs and furloughs (Cox, 2020), creating uncertainty for hotel employees with regard to their earnings, job status, and even career development. Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to major challenges in staff recruitment and employee retention for hotel managers (Filimonau et al., 2020).

Faced with these challenges, hotels are helping their employees survive by establishing relief funds, offering alternative work arrangements, and providing education and training programs (Fox, 2020). Many organizations believe that increasing employees’ career adaptability through education and training can help them cope with workplace challenges during this difficult time (Rasheed et al., 2020). Heath (2020) stated that career adaptability could help individuals see the possibilities in unanticipated changes, capitalize on those changes, and recover from unforeseeable outcomes. Proactive personality is another important trait of employees who work in hospitality management (Yang et al., 2020). Researchers have found that proactive employees are likely to be well prepared for career-related changes (Tolentino et al., 2014), and proactive personality is a critical factor affecting the formation of career adaptability (Jiang, 2017; Tolentino et al., 2014). While increased career adaptability is generally perceived as a positive characteristic, it is not always beneficial to employers. On one hand, career adaptability is associated with positive outcomes, such as higher job satisfaction (e.g., Chan et al., 2016; Guan et al., 2015), and consequently, lower turnover intentions (e.g., Rasheed et al., 2020); on the other hand, career adaptability can be a double-edged sword and may lead to higher voluntary turnover intentions (e.g., Ito & Brotheridge, 2005; Karatepe & Olugbade, 2017). To date, it is still unclear how career adaptability impacts employees’ turnover intentions.

Considering the major impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hotel labor market, highly adaptable employees may indeed seek opportunities outside their current companies. In other words, highly adaptable individuals may be less dependent on their current employers and exhibit higher turnover intentions. Such an argument can be especially relevant during the pandemic because of the uncertainty surrounding their jobs. Addressing this research gap is critically important, given its increased salience during the pandemic. While hotel managers may want to provide opportunities to increase their employees’ career adaptability and help them cope with pandemic-related challenges, they also need assurances that those efforts and investments will not inadvertently lead to higher turnover rates.

To reconcile the mixed findings in the literature, we propose a model that accounts for the moderating role of work social support (i.e., supervisor support and coworker support) in the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. From a social exchange theory perspective, employees make commitments to their employers in exchange for support in the workplace (Eisenberger et al., 1990), which results in mutually rewarding relationships (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Social exchange theory can be a helpful lens for analyzing relationships among career adaptability, work social support, and turnover intentions (Eisenberger et al., 1986). When employees receive strong work social support, they are more committed to the organization and consequently are more likely to be adaptable within the company. On the contrary, when employees receive weak work social support, they feel less obligated to stay with their current employer. Those highly adaptable employees may seek opportunities outside the company, resulting in higher voluntary turnover.

In sum, we aim to examine (a) the impact of proactive personality on career adaptability, and (b) the moderating role of work social support on the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. Findings from this study will not only contribute to the career adaptability literature in the hospitality field, but also will help hotel managers retain valuable talent in the future after the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Career adaptability

Career adaptability is described as a psychological resource that enables individuals to handle challenges in their careers (Savickas, 1997). According to career construction theory, individuals with higher career adaptability possess more significant transactional competencies and more psychosocial resources that enable them to adapt to and successfully deal with tasks, transitions, and traumas in their careers (Savickas, 1997). The model associated with this theory focuses on the individual’s role in the workplace and addresses social expectations and how the individual handles subsequent career transitions (Savickas et al., 2009). Savickas (2005) later redefined career adaptability as “a psychosocial construct that denotes an individual’s readiness and resources for coping with current and imminent vocational development tasks, occupational transitions, and personal traumas” (p. 51). Career adaptability is viewed as an array of behaviors, competencies, and attitudes that make individuals better suited to particular jobs (Tolentino et al., 2013).

Career adaptability can be triggered or developed during career-related events or changes (Ocampo et al., 2020). It can also be fostered by different high-performance work practices such as formal employee training, high pay levels, and group-based performance pay (Safavi & Karatepe, 2018). On one hand, individuals can increase their own career adaptability to strengthen their capacity to handle occupational changes (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012); on the other hand, managers can help employees increase their career adaptability to enhance their fit with the workplace and effectively manage career changes and challenges (Zacher et al., 2015). The resources of adaptability (also called “adapt-abilities”) are concern, control, curiosity, and confidence (Savickas, 2005). Concern involves planning for the future, control implies a personal responsibility to shape the future, curiosity leads to exploring possible roles, and confidence is belief in one’s ability to achieve goals and implement choices (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012).

Extant literature has shown that career adaptability is positively related to career success, job performance (Yu & Zheng, 2013), and employee well-being (Ohme & Zacher, 2015). It has also been established as a significant predictor of various positive career outcomes, including promotability (Tolentino et al., 2013), employment status (Guan et al., 2014), career satisfaction (Zacher, 2014), successful career transitions and career counseling (Brown et al., 2012), reduced career anxiety and work stress (Maggiori et al., 2013), and higher job satisfaction and work engagement (Rossier et al., 2012).

Consequently, career adaptability can be especially vital in a crisis. During a global crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, career adaptability can be perceived as an important skill in the workplace, as significant economic changes drive involuntary job changes, layoffs, and furloughs. Career adaptability may help individuals see the possibilities in unanticipated changes, capitalize on those changes, and recover from unforeseeable outcomes (Rudolph et al., 2017). It may also help people respond to changes in a calm and composed manner (Tripathy, 2020) and stimulate more possibilities in a complicated situation (Ginevra et al., 2018).

However, while career adaptability tends to help employees cope with challenges during difficult times, it is not clear whether employees with high career adaptability would work to find solutions within their current companies or seek employment opportunities elsewhere. Findings in the extant literature are mixed. To date, it is unclear how career adaptability would impact voluntary turnover intentions. In addition, although past research has explored the consequences of career adaptability, relatively scant attention has been paid to the antecedents of this construct (Ramos & Lopez, 2018). Therefore, we also examine proactive personality as an important antecedent of career adaptability. In the following sections, we introduce proactive personality as an antecedent of career adaptability before elaborating the moderating role of work social support in the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. Based on these insights, we propose a moderated mediation model among proactive personality, career adaptability, and turnover intentions.

2.2. Career adaptability and proactive personality

Researchers have examined stable personality traits as predictors of career adaptability in a number of studies. For example, Rudolph et al. (2017) performed a meta-analysis and found that all the Big Five personality traits predict career adaptability. In particular, two traits, conscientiousness and openness, are the strongest predictors of career adaptability (Zacher, 2016). This means that individuals who score higher on these traits are better able to adapt and cope with career challenges (Storme et al., 2020). Other traits or characteristics that have been found to predict career adaptability include self-esteem and regulatory focus (van Vianen et al., 2012), emotional intelligence (Celik & Storme, 2018), core self-evaluations (Zacher, 2014), and future orientation (Rudolph et al., 2017).

In the current research, we examine proactive personality - a relatively stable characteristic driving people to act on initiatives to impact their circumstances (Bateman & Crant, 1993; Jiang, 2017) - as an antecedent of career adaptability. Extant literature has found that proactive personality explains “unique variance in criteria over and above that accounted for by the Big Five personality factors” (Bakker et al., 2012, p. 1360). In the hospitality industry, proactive personality is a particularly important personality trait for employees, because those who are proactive take personal initiative in various circumstances, which enables them to rapidly adapt to customers’ ever-changing needs and deliver high-quality service (Yang et al., 2020).

Consistent with personal agency in career construction theory (Del Corso & Rehfuss, 2011), the proactive perspective argues that proactive individuals can successfully improve situations to better suit their needs and preferences. As a result, those with more proactive personalities are better prepared to handle career tasks and transitions than those with less proactive personalities (Jiang, 2017). Prior research has also demonstrated that proactive workers are intrinsically motivated to actively improve the constrained environment via positive coping strategies (Zhao & Guo, 2019). Thus, individuals who are more proactive, open to change, and flexible tend to manage their careers more effectively than those who are more passive recipients of environmental constraints. Therefore, we anticipate that proactive employees are able to be responsive, and to actively shape the work environment and develop career adaptability resources. We hypothesize:

H1

Proactive personality is positively related to career adaptability.

2.3. Career adaptability and turnover intentions

Findings in the extant literature are mixed regarding the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. Some studies suggest a positive association between career adaptability and turnover intentions (e.g., Ito & Brotheridge, 2005; Karatepe & Olugbade, 2017) whereas others reveal a negative relationship between the two (e.g., Zhu et al., 2019). For example, some scholars argue that career adaptability enables employees to adapt well to the changing work environment, which then leads to a positive attitude toward their careers within their organizations (Chan & Mai, 2015; Omar & Noordin, 2013). This positive attitude further enhances their willingness to maintain good relationships with their supervisors and coworkers. Therefore, employees with high career adaptability may be more likely to stay within their organizations (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012).

In contrast, other studies reveal that employees with high career adaptability tend to have higher intentions to leave their current companies (Ito & Brotheridge, 2005; Yu & Zheng, 2013). Roehling et al. (2000) argued that security from career adaptability does not stay between employee and employer but rather in the employees’ ability to adapt to change and even take advantage of other opportunities. Strong career adaptability not only makes employees more qualified for employment opportunities in other organizations, but also increases mobility and the willingness to take advantage of such opportunities (Ito & Brotheridge, 2005), which may increase voluntary turnover (Stroh et al., 1996). Guan et al. (2014) re-emphasized that employees with high levels of career adaptability are more open to potential career changes, which mirrors findings showing that those with high career adaptability are also highly aware of alternate career options (Savickas, 2013; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Furthermore, a high level of career adaptability may enable employees to put forth the effort necessary to scan for possible career options (Zacher et al., 2015).

In fact, when employees strengthen their career adaptability, they enhance their employability, not only within, but also outside their organizations (Waterman et al., 1994). Therefore, career adaptability may lead to increased employee turnover because they feel that they are more qualified and actively seek employment opportunities in other organizations (Ito & Brotheridge, 2005). In other words, whereas career adaptability may reduce risks for employees, it may increase risks for employers that invest in augmenting employees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities. Although career adaptability is an important skill to help employees adapt and facilitate future career development (e.g., Hou et al., 2012), the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions is rather inconclusive. In examining whether highly adaptive employees tend to stay in their current organizations during the pandemic or actively seek outside opportunities to advance their careers, we consider the moderating role of work social support.

2.4. Work social support

Social support is defined as “an interpersonal transaction that involves emotional concern, instrumental aid, information, or appraisal” (Carlson & Perrewe, 1999, p. 514). Social support is potentially an important socialization source (Saks & Gruman, 2011) and is regarded as a coping mechanism in the work setting and even in the family domain (Aryee et al., 2005). Social support in the workplace may help employees cope with difficulties associated with roles at work (Frye & Breaugh, 2004; Karatepe & Kilic, 2007), and may also help them integrate work and family roles more effectively (Demerouti et al., 2004; Hill, 2005). Karatepe and Bekteshi (2008) highlighted social support as a platform to reduce emotional exhaustion, and suggested that a work environment that promotes social support can enable individuals to pursue different career roles and manage their career transitions. Therefore, work social support is an integral part of the social support system in the workplace (Karatepe, 2013; Michel et al., 2013).

In this study, we focus on supervisor support and coworker support, which are two of the most important forms of social support for employees (Liaw et al., 2010). Support from supervisors includes offering assignments that help employees develop and strengthen new skills, taking time to help them develop career goals, providing access to training to advance their careers, and providing performance feedback (Kidd & Smewing, 2001; Wickramasinghe & Jayaweera, 2010). Support from coworkers includes career guidance and information from colleagues, training that enables the development of new skills, and workplace friendships. Such supportive relationships from colleagues are able to enhance employees’ satisfaction with their careers within their organizations (Karatepe & Olugbade, 2017). Insufficient social support at work may create stress for employees (Parasuraman et al., 1992); on the contrary, substantial work social support can minimize the potential for conflict in the workplace (Karatepe, 2010), reduce work-related stress (Karatepe & Bekteshi, 2008), encourage increased career satisfaction (Guan et al., 2015), and make employees less vulnerable to exhaustion (Cole & Bedeian, 2007).

2.5. Career adaptability and work social support

Psychosocial work environment is not only about the job itself but also the nature and quality of the workplace norms, such as interpersonal relations and interactions between organizational actors, i.e., employees (Hammer et al., 2004). Social exchange theory (SET) is one the most influential concepts in organizational behavior (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). According to Emerson (1976), social exchange involves interactions that create obligations. Such interactions are interdependent on the actions of another party (Blau, 1964), and have the potential to generate a high-quality relationship (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Social exchange includes actions contingent on the rewarding reactions of others, which over time establish mutually rewarding relationships (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

In the workplace, social exchange involves employees exchanging their commitment for an employer’s support (Eisenberger et al., 1986, 1990). For example, Wayne et al. (1997) found that organizations play an important role in building employees’ affective commitment through perceptions of organizational support by providing resources that enable proactive career development, such as training and development programs and challenging job assignments that foster feelings of personal growth. According to SET, the decision to leave the company is affected by relational inducements such as a lack of work-related support from an employee’s organization, supervisor, and coworkers (Maertz et al., 2007). Employees are less likely to consider leaving when they feel that their work efforts are being supported by their organizations or their supervisors (Dawley et al., 2008). SET thereby provides a rationale for examining the moderating role of work social support between career adaptability and turnover intentions (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Whitener & Walz, 1993).

On one hand, career adaptability may lead to lower turnover intentions (e.g., Chan et al., 2016; Guan et al., 2015); on the other hand, more adaptable employees may be less dependent on their companies and have higher turnover intentions (e.g., Ito & Brotheridge, 2005; Karatepe & Olugbade, 2017), especially during times of uncertainty, such as the current pandemic. Drawing on SET, we argue that the level of work social support, including both supervisor and coworker support impacts the relationship between employees’ career adaptability and turnover intentions. Supervisors and coworkers are important actors who can build strong emotional and social bonds with employees. Both supervisors and coworkers provide support in the form of formal and informal feedback on task performance as well as encouragement regarding career development (Peng & Zeng, 2017). Such support can help employees meet their career goals, achieve continuous advancement, and become valued members of the company. As a result, with strong supervisor support and coworker support, employees with high career adaptability should be more likely to stay in their current organizations to cope with challenges and further advance their careers (Zhu et al., 2019).

On the contrary, when employees have lower perceptions of supervisor and coworker support, they may experience lower levels of affective commitment and feel less obligated to stay within their current organizations (Maertz et al., 2007). In such situations, employees with high career adaptability likely would seek opportunities outside the current company to advance their careers and exhibit higher turnover intentions due to a lack of support. Taken together, we propose that the influence of career adaptability on turnover intentions depends on work social support, which includes both supervisor and coworker support.

H2a

When supervisor support is low, employees with high career adaptability level show a higher turnover intention than those with low career adaptability level.

H2b

When coworker support is low, employees with high career adaptability level show a higher turnover intention than those with low career adaptability level.

H3a

When supervisor support is high, employees with high career adaptability level show a lower turnover intention than those with low career adaptability level.

H3b

When coworker support is high, employees with high career adaptability level show a lower turnover intention than those with low career adaptability level.

2.6. A moderated mediation model

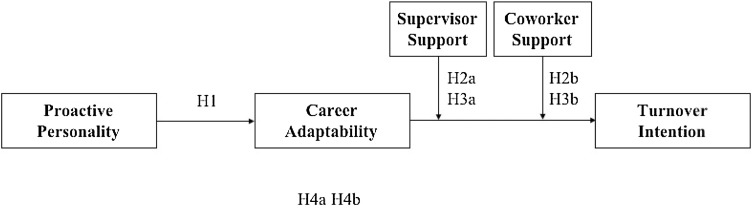

Aligned with the discussions and hypotheses above, it is anticipated that a moderated mediation effect exists, such that both supervisor and coworker support moderate the indirect relationship between proactive personality and turnover intentions through career adaptability. More specifically, it is anticipated that the indirect relationship is negative (e.g., higher proactive personality is associated with lower turnover intentions) when supervisor support and coworker support are high, and the indirect relation is positive (e.g., higher proactive personality is associated with higher turnover intentions) when supervisor support and coworker support are low. The conceptual framework is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

H4a

Supervisor support moderates the indirect relationship between proactive personality and turnover intentions (via career adaptability), such that the indirect relationship is negative when supervisor support is high, and is positive when supervisor support is low.

H4b

Coworker support moderates the indirect relationship between proactive personality and turnover intentions (via career adaptability), such that the indirect relationship is negative when coworker support is high, and is positive when coworker support is low.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Research methods

3.1. Study design and participants

We designed a quantitative survey to test our moderated mediation model. The survey began with several screening questions to ensure all participants had been working in the hotel industry in the U.S. for at least 6 months and were currently in an active full-time employment status (e.g.: Are you currently in an active full-time employment status in a hotel company? Have you been working in the hotel industry for more than 6 months?). Then, major variables including proactive personality, career adaptability, supervisor/coworker support, and turnover intentions were captured. Respondents were also asked to indicate their general perceptions of how much the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted their work (i.e., “To what extent do you feel the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the hotel you are currently working at and its employees?” 1 = not at all, 7 = extremely so). Basic demographic information about the respondents were captured at the end of the survey.

A total of 339 valid responses were collected from Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk) during June 2020. MTurk is a popular tool for data collection that has been used successfully in various research fields, including hospitality and tourism (e.g., Dedeke, 2016; Zhang & Yang, 2019). As an incentive, a 50-cent credit was deposited in each respondent’s Amazon account after completing the survey. On average, respondents were 35.20 years old and had been working at their current hotels for 4.76 years. Among all respondents, 42.6 % were female; the majority (75.3 %) had a bachelor’s degree or higher; 63.1 % were Caucasian, followed by African American (17.3 %) and Asian (11.0 %). About 32.7 % of respondents reported annual household incomes between $40,000 and $59,999, and 22 % reported annual household incomes between $60,000 and $79,999. Respondents worked in various departments in a hotel such as the front office (26 %), food and beverage (14.7 %), accounting and finance (13.9 %), and housekeeping (9.4 %). 41.7 % of the respondents held supervisory positions, followed by entry-level positions (31.5 %) and managerial positions (22.4 %).

3.2. Measurements

All measurement items for key variables were adopted from existing studies, and utilized seven-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Proactive personality was captured using four items from Bateman and Crant’s (1993) study (e.g., “I am always looking for better ways to do things;” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.825). We adopted four items from Karasek et al.’s (1982) study to measure supervisor support (e.g., “My supervisor shows me how to improve my performance;” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.847) and four items from Hammer et al. (2004) to measure coworker support (e.g., “My coworkers back me up when I need it;” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.833). We measured career adaptability using 24 items adopted from Savickas and Porfeli (2012) (e.g., “Planning how to achieve my goals” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.966). We measured turnover intentions using three items from McGinley and Mattila (2020) (e.g., “I think a lot about leaving my current hotel;” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.892).

4. Results

Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlation estimates for the key constructs in this study are provided in Table 1 , along with results showing the convergent validity of major variables. The Harman’s single factor test was performed to examine the common method bias. The result showed that the single factor explained 45.47 % of the variance which is below the 50 % cutoff point (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In addition, a common latent factor method was also employed to compare the standardized regression weights of all items for models with and without common latent factor. The differences were found to be very small (< 0.2) which further confirmed that common method bias is not a major issue in our data (Gaskin, 2017).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables.

| M | SD | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Proactive personality | 5.46 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.53 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Career adaptability | 5.31 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.54 | 0.75* | 1 | |||

| 3. Supervisor support | 5.32 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 0.66* | 0.68* | 1 | ||

| 4. Coworker support | 5.45 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.57 | 0.69* | 0.68* | 0.74* | 1 | |

| 5. Turnover intentions | 4.13 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 0.73 | −0.17* | −0.15* | −0.21* | −0.22* | 1 |

Note. n = 339 * p < 0.01.

A confirmatory factor analysis was then conducted to test the measurement model. The results indicated an acceptable fit to the data with normed χ² = 1.845, CFI = 0.936, and RMSEA = 0.05. In addition, all factor loadings were significant and higher than 0.6. Average variance extracted (AVE) by each latent factor is greater than 0.5, and all composite reliability scores (CR) are higher than 0.8, thus providing evidence of good convergent validity. Results of discriminant validity tests are presented in Table 2 in the form of heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios. HTMT is the average of the heterotrait-heteromethod correlations relative to the average of the monotrait-heteromethod correlations. This new method outperforms classic approaches to discriminant validity assessment such as the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Henseler et al., 2015). All HTMT values in the current study are below 0.90, indicating good discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). Please see Table 2.

Table 2.

HTMT Analysis for Discriminant Validity.

| Variable | Proactive personality | Career adaptability | Supervisor support | Coworker support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career adaptability | 0.845 | |||

| Supervisor support | 0.825 | 0.744 | ||

| Coworker support | 0.847 | 0.753 | 0.884 | |

| Turnover intentions | 0.223 | 0.163 | 0.249 | 0.258 |

4.1. Hypotheses testing

In the proposed moderated mediation model shown in Fig. 1, proactive personality is the independent variable, career adaptability is a mediator, supervisor support and coworker support are moderators, and turnover intentions is the dependent variable. We used Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS procedure (Model 14) with the recommended bias-corrected bootstrapping technique (5,000 replications) to test the proposed model. Because the model has two moderators, we ran two separate PROCESS models: one with supervisor support as a moderator and the other with coworker support as a moderator. We included respondents’ age, gender, and current tenure in the hotel as control variables because employee demography is related to turnover intentions (Chen & Francesco, 2000; Hochwarter et al., 2001). We also controlled for respondents’ perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on the hotels where they were currently working (Jung et al., 2020). All continuous variables were mean-centered to reduce multicollinearity.

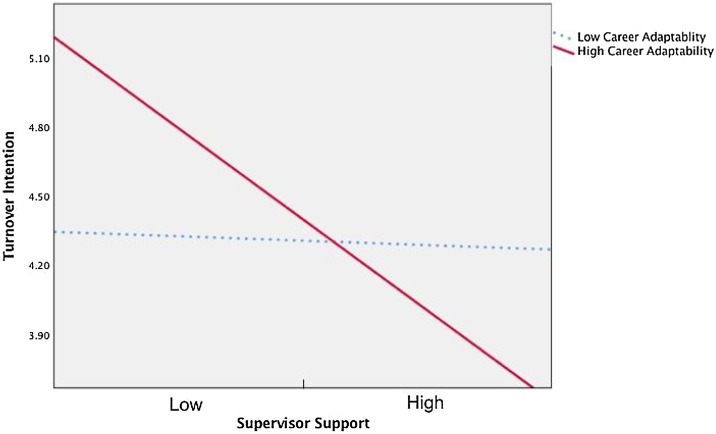

The PROCESS results reveal that a significant positive relationship exists between proactive personality and career adaptability (b = 0.76, p < 0.001) supporting Hypothesis 1. H2aH2a aH3aa aH3a propose that supervisor support mos the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. The interaction between supervisor support and career adaptability is statistically significant (b = −0.76, p < 0.001). These results are summarized in Table 3 . Consistent with H2a, with H2a, a spotlight reveals that at lower levels of supervisor support (1 SD below the mean), career adaptability is positively associated with employees’ turnover intentions (b = 0.38, p = 0.002). In contrast, when employees receive higher levels of supervisor support (1 SD above the mean), career adaptability is negatively associated with turnover intentions (b = −0.28, p = 0.08), providing marginal support for H3a. rt for H3H3aais t for H3H3aais margi (p < 0.1), the interaction between supervisor support and career adaptability is indeed statistically significant (b = −0.76, p < 0.001), suggesting that supervisor support moderates the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. This moderation effect is graphically depicted in Fig. 2 , such that when supervisor support is low, employees with high career adaptability have higher turnover intentions than those with low career adaptability. However, when supervisor support is high, employees with high career adaptability have lower turnover intentions than those with low career adaptability.

Table 3.

Results for moderated mediation (supervisor support as moderator).

| Predictors | Coefficient | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career adaptability regressed on: | ||||

| Constant | −4.658** | −17.020 | −5.109 | −4.207 |

| Proactive personality | 0.763** | 18.559 | 0.695 | 0.831 |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.273 | −0.007 | 0.005 |

| Current tenure | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.013 | 0.013 |

| Gender | 0.024 | 0.386 | −0.080 | 0.129 |

| Perceived COVID-19 impact | 0.086** | 2.845 | 0.036 | 0.136 |

| R2 = .571, p < .01 | ||||

| Turnover intentions regressed on: | ||||

| Constant | 4.964** | 5.144 | 3.372 | 6.556 |

| Proactive personality | −0.142 | −0.945 | −0.391 | 0.106 |

| Career adaptability (CA) | 0.052 | 0.359 | −0.187 | 0.291 |

| Supervisor support (SS) | −0.373** | −2.891 | −0.586 | −0.160 |

| Interaction CA * SS | −0.376** | −4.131 | −0.526 | −0.226 |

| Age | −0.003 | −0.300 | −0.017 | 0.012 |

| Current tenure | 0.022 | 1.172 | −0.009 | 0.053 |

| Gender | −0.118 | −0.756 | −0.376 | 0.140 |

| Perceived COVID-19 impact | 0.057 | 0.759 | −0.067 | 0.181 |

| R2 = 0.102, p < 0.01 | ||||

Note. n = 339 ** p < -0.01.

LLCI: 95 % lower level confidence interval; ULCI: 95 % upper level confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

The moderating role of supervisor support.

In addition, Hypothesis 4a predicts a conditional indirect effect whereby the indirect relationship between proactive personality and turnover intentions is moderated by supervisor support. Results for conditional indirect effects are presented in Table 4 . Specifically, the indirect effect of proactive personality is significant and positive when supervisor support is low (b = 0.29; 95 % CI: 0.086, 0.423), but is significant and negative when supervisor support is high (b = −0.21; 95 % CI: −0.449, −0.005). Hayes’s (2013) index of moderated mediation also provides a way to test the strength of the mediator at different levels of the moderator, and the results are significant (moderated mediation index = −0.287; SE = .077; 95 % CI: −0.427, −0.171), thus supporting H4a.

Table 4.

Conditional effect of proactive personality on turnover intentions through career adaptability for various values of supervisor support.

| Mediator | Supervisor Support | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career adaptability | −1 SD | .293 | .132 | .086 | .523 |

| 0 | .040 | .115 | −.146 | .228 | |

| +1 SD | −.213 | .135 | −.449 | −.005 |

Note. LLCI: 95 % lower level confidence interval; ULCI: 95 % upper level confidence interval.

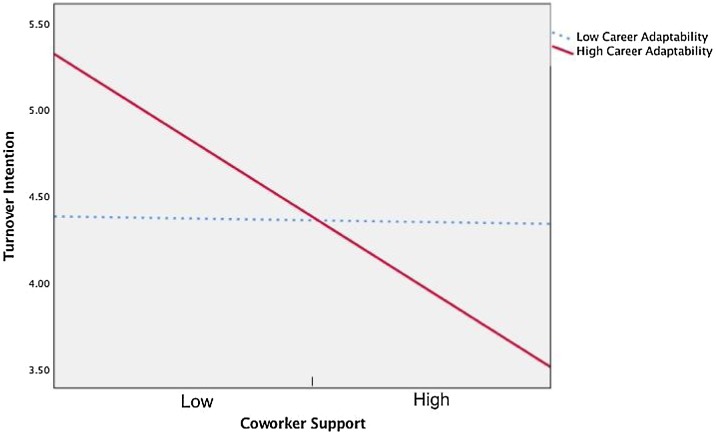

Another PROCESS model was tested using the same variables, but replacing the moderator with coworker support to test H2b, H3b and H4b. H2b and H3b predict that coworker support moderates the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. The predicted interaction between coworker support and career adaptability is statistically significant (b = −0.44, p < 0.001). These results are summarized in Table 5 . Consistent with H2b, a spotlight analysis reveals that at lower levels of coworker support (1 SD below the mean), career adaptability is positively associated with employees’ turnover intentions (b = 0.42, p = 0.001). In contrast, at higher levels of coworker support (1 SD above the mean), career adaptability is negatively associated with turnover intentions (b = −0.36, p = 0.03), thus supporting H3b. This moderation effect is graphically depicted in Fig. 3 , such that when coworker support is low, employees with high career adaptability have higher turnover intentions than those with low career adaptability. On the contrary, when coworker support is high, employees with high career adaptability have lower turnover intentions than those with low career adaptability.

Table 5.

Results for moderated mediation (coworker support as moderator).

| Predictors | Coefficient | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career adaptability regressed on: | ||||

| Constant | −4.658** | −17.020 | −5.109 | −4.207 |

| Proactive personality | 0.763** | 18.559 | 0.695 | 0.831 |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.273 | −0.007 | 0.005 |

| Current tenure | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.013 | 0.013 |

| Gender | 0.024 | 0.386 | −0.080 | 0.129 |

| Perceived COVID-19 impact | 0.086** | 2.845 | 0.036 | 0.136 |

| R2 = .571, p < .01 | ||||

| Turnover intentions regressed on: | ||||

| Constant | 4.726** | 4.775 | 3.094 | 6.359 |

| Proactive personality | −0.092 | −0.598 | −0.347 | 0.163 |

| Career adaptability (CA) | 0.031 | 0.221 | −0.203 | 0.266 |

| Coworker support (CS) | −0.417** | −3.080 | −0.640 | −0.194 |

| Interaction (CA * CS) | −0.442** | −4.434 | −0.606 | −0.277 |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.151 | −0.016 | 0.013 |

| Current tenure | 0.018 | 0.943 | −0.013 | 0.049 |

| Gender | −0.131 | −0.842 | −0.387 | 0.125 |

| Perceived COVID-19 impact | 0.056 | 0.742 | −0.068 | 0.180 |

| R2 = .109, p < .01 | ||||

Note. n = 339 ** p < 0.01.

LLCI: 95 % lower level confidence interval; ULCI: 95 % upper level confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

The moderating role of coworker support.

Hypothesis 4b proposes a conditional indirect effect whereby the indirect relationship between proactive personality and turnover intentions is moderated by coworker support. Results for conditional indirect effects are presented in Table 6 . Specifically, the indirect effect of proactive personality is significant and positive when coworker support is low (b = 0.32; 95 % CI: 0.123, 0.528), but is significant and negative when coworker support is high (b = −0.27; 95 % CI: −0.512, −0.038). Hayes’s (2013) index of moderated mediation is also significant (moderated mediation index = −0.337; SE = 0.08; 95 % CI: −0.476, −0.214), thus supporting H4b.

Table 6.

Conditional effect of proactive personality on turnover intention through career adaptability for various values of coworker support.

| Mediator | Coworker support | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career adaptability | −1 SD | .320 | .124 | .123 | .528 |

| 0 | .024 | .115 | −.166 | .212 | |

| +1 SD | −.272 | .144 | −.512 | −.038 |

Note. LLCI: 95 % lower level confidence interval; ULCI: 95 % upper level confidence interval.

5. Discussion

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the hospitality industry may no longer be perceived as an attractive employment sector. To avoid losing talent in the industry during and after the pandemic, hotel managers must equip their staff to be adaptable in such difficult moments. However, it was still unclear how career adaptability impacts intentions to leave, especially during critical times. This study provided empirical evidence to support a moderated mediation effect of work social support (i.e., support from supervisors and coworkers) in the relationship between employees’ proactive personality and turnover intentions through career adaptability. The findings from this study have several theoretical and managerial implications.

5.1. Theoretical contributions

Career adaptability is a relatively new concept which merits attention from hospitality scholars (Rasheed et al., 2020). Our study enriches the literature of career adaptability in hospitality management by revealing a conditional effect of work social support on the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. The current research represents an important attempt to direct the attention of researchers to this phenomenon in the hospitality industry, a dynamic context in which already high levels of employee turnover have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, many hotels ask employees to be furloughed or on unpaid leave, which is a short-term solution financially speaking. During unpaid leave or furlough, it is possible that some employees may leave their companies and look for other opportunities. However, when the industry business is back on track, it will be expensive to recruit and hire again. The current study suggests that highly adaptable employees may indeed exhibit higher turnover intentions and seek opportunities outside their current companies during the pandemic. Therefore, enhancing employees’ career adaptability with substantial work social support is vital to retain talents during this difficult time. According to social exchange theory, the decision to leave the company is affected by relational inducements, such as a lack of work-related support (Maertz et al., 2007). Employees, no matter if they are still working in the companies, having furloughed, or having unpaid leave, are less likely to consider leaving when they feel that their work efforts are being supported by their organizations or supervisors (Dawley et al., 2008).

In particular, our study reveals supervisor and coworker support as key boundary conditions affecting the relationship between career adaptability and turnover intentions. Our findings suggest that the higher employees’ career adaptability, the lower their intentions to leave when they perceive high supervisor and coworker support. In contrast, although career adaptability increases psychological resources, which enables employees to advance their careers within their current companies (Rasheed et al., 2020), the findings reveal that high levels of career adaptability do not mitigate employees’ intentions to quit if employees perceive little support in the workplace. Thus, our study has identified work social support as an important moderator regarding when employees’ career adaptability supports or undermines employee retention. The results highlight the critical roles of supervisor and coworker support in the literature, complementing SET (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). The positive impact of employees’ career adaptability on their turnover intentions when they perceive lower supervisor and coworker support is an important finding which has implications for future research and applications.

We not only examined the relationship between employees’ career adaptability and turnover intentions through supervisor and coworker support, but also investigated proactive personality as an important predictor of career adaptability in this theoretical model. Although a review of the literature suggests that researchers have explored the consequences of career adaptability, relatively scant attention has been paid to the antecedents of career adaptability (Ramos & Lopez, 2018). This research has answered this call by identifying proactive personality as an important antecedent. This result is aligned with the assumption of career construction theory that employee proactive personality is anchored in self-regulation capacities to respond and adapt to life and work situations successfully (Tolentino et al., 2013). The current research answers the question of how employee proactive personality predicts career adaptability, which in turn is related to turnover intentions via the moderating effect of work social support in the forms of supervisor and coworker support. Because career adaptability helps frontline workers adapt to the rapidly changing hospitality environment, and given the value of career adaptability to frontline workers (Safavi & Bouzari, 2019), it is expected that the findings could be generalized to other service sectors such as restaurants and theme parks facing similar issues.

5.2. Practical implications

Findings from this study also have several valuable managerial implications that may help hotel managers identify opportunities to increase their employees’ career adaptability while reducing their employees’ turnover intentions. Career adaptability is a crucial competency to help employees cope with changing working conditions like those created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS) can be used to quantitatively measure employees’ adaptability across different cultural settings, different job levels, and different job categories (Ito & Brotheridge, 2005; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Managers can analyze employees’ career-related needs and then design interventions to promote feasible adjustments to work conditions. Promoting and reinforcing career adaptability can help employees effectively manage changes and challenges in their careers. It is also necessary to develop managers’ career adaptability resources by providing access to career interventions such as orientation programs, decision-making training, information-seeking activities, and self-esteem building exercises (Savickas, 2005, 2013). Organizations also can provide staff with self-development resources such as tuition reimbursement programs and opportunities for learning, training, and cross-exposure to other properties within the hotel chain, which may increase employees’ career adaptability and their commitment to the organization. In addition, managers may consider using career adaptability as a selection criterion in recruitment in the post-pandemic era to identify high-potential candidates in their companies. With a highly adaptable workforce, training and job rotation programs can be an effective way to enhance employees’ career adaptability (Guan et al., 2016).

More importantly, when helping employees enhance career adaptability, it is vital to provide strong work social support to avoid triggering higher turnover intentions. The current study reveals the important role of strong supervisor support and coworker support in retaining highly adaptable employees. In general, supervisor support consists of offering helpful feedback about work performance, keeping subordinates informed about career opportunities, mentoring, and supporting subordinates’ attempts to acquire additional training or education to advance their careers. More specifically, during a crisis, supervisors and managers need to provide career support in order to recoup investments in developing the knowledge, skills, and abilities of their subordinates to reduce highly adaptable employees’ intentions to leave (Ito & Brotheridge, 2005). It is also important for hotels to train their managers and supervisors to be capable, available, and resourceful to support their staff. Such training is needed to strengthen awareness and help managers and supervisors develop the skills necessary to offer potential remedies and support to employees in accordance with the policies of the company and relevant authorities. Managers and supervisors should also strive to address the personal needs of employees, especially those who are still working. Furthermore, organizational leaders who can identify and address employees’ interpersonal needs can be powerful catalysts in promoting work social support (Singh et al., 2018). Division heads should show compassion and trustworthiness and implement real-time measures of support for employees’ mental health during this difficult time (Ahmed et al., 2020). Employers can also promote supervisor support via social networking technology by establishing a platform where employees can discuss and manage their issues or problems, which in turn, organizations can enhance a supportive work environment that supports their employees’ career goals and emotional well-being (Papagiannidis, & Marikyan, 2020).

Beyond strengthening supervisor support in the workplace, it is essential for coworkers to provide strong work social support during difficult times. Managers may encourage informal social relationships among employees in the organization to facilitate positive interactions. Holding orientation sessions for employees who hold similar positions both within and across departments may reinforce bonding among coworkers. Furthermore, it is necessary to re-establish connections amongst members of the workforce who are furloughed, laid off, or on unpaid leave. By maintaining relationships among coworkers, employees can strengthen their connections within the organization and reinforce their sense of worth. It is critically important for employers to establish a friendly workplace climate (including friendship opportunities and friendship prevalence) for their employees (Zhuang et al., 2020). Fostering positive and professional relationships within departments is an important way to demonstrate coworker support. Regular Zoom meetings, group chats, or any forms of interactive communication, such as creating social media groups for staff members to post and share their daily activities, are recommended (Schinoff et al., 2020).

6. Limitations and future research directions

As with all research, it is important to acknowledge several limitations of this study which may provide potential avenues for further research. First, because the pandemic is ongoing, this study only captured respondents’ turnover intentions rather than their actual behaviors. A longitudinal study could be conducted to capture actual turnover behaviors after the pandemic. Second, although we proposed a moderated mediation model and examined the moderating roles of both supervisor and coworker support, we did not perform a fine-grained analysis that considered respondents’ work profiles, such as the nature of their jobs (front of the house vs. back of the house, line level vs. managerial positions). In future studies, researchers could consider collecting data on respondents’ work profiles. It is possible that the impact of supervisor vs. coworker support may vary across different departments and positions.

Furthermore, additional research on career adaptability is warranted. In this study, we investigated one predictor, proactive personality, and how this links to turnover intentions through the moderating role of workplace support. Future studies are needed to identify other antecedents and outcomes of career adaptability. In addition, the sample was composed entirely of U.S. residents who work in the hotel industry, which might limit the generalizability of the results. Although previous studies have not found cross-cultural differences in career adaptability (Rasheed et al., 2020), researchers should replicate our study using samples from other countries. Lastly, we focused only on the hotel industry in the current study. Other sectors of the hospitality and tourism industry such as restaurants and theme parks may have different work structures and generate different results regarding supervisor/coworker support. In the future, researchers could examine how unique features of different sectors influence the relationships among employee proactive personality, career adaptability, workplace support, and turnover intentions.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Ahmed F., Zhao F., Faraz N.A. How and when does inclusive leadership curb psychological distress during a crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01898. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Hotel & Lodging Association (AHLA) 2020. COVID-19's Impact on the Hotel Industry. Retrieved on October 10, 2020 from https://www.ahla.com/covid-19s-impact-hotel-industry. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S., Srinivas E.S., Tan H.H. Rhythms of life: antecedents and outcomes of work-family balance in employed parents. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005;90(1):132–146. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Tims M., Derks D. Proactive personality and job performance: the role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012;65(10):1359–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman T.S., Crant J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: a measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993;14(2):103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Baum T., Hai N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blau P.M. John Wiley; New York, NY: 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A., Bimrose J., Barnes S.A., Hughes D. The role of career adaptabilities for mid-career changers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012;80(3):754–761. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson D.S., Perrewe P.L. The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: an examination of work-family conflict. J. Manage. 1999;25(4):513–540. [Google Scholar]

- Celik P., Storme M. Trait emotional intelligence predicts academic satisfaction through career adaptability. J. Career Assess. 2018;26(4):666–677. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.H.J., Mai X. The relation of career adaptability to satisfaction and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015;89:130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.H., Mai X., Kuok O.M., Kong S.H. The influence of satisfaction and promotability on the relation between career adaptability and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016;92:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.X., Francesco A.M. Employee demography, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions in China: do cultural differences matter? Hum. Relat. 2000;53(6):869–887. [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.S., Bedeian A.G. Leadership consensus as a cross-level contextual moderator of the emotional exhaustion-work commitment relationship. Leadersh. Q. 2007;18(5):447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. 2020. A Record 20.5 Million Jobs Were Lost in April As Unemployment Rate Jumps to 14.7%https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/08/jobs-report-april-2020.html May 8, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., Mitchell M.S. Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manage. 2005;31(6):874–900. [Google Scholar]

- Dawley D.D., Andrews M.C., Bucklew N.S. Mentoring, supervisor support, and perceived organizational support: what matters most? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008;29:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Dedeke A.N. Travel web-site design: information task-fit, service quality and purchase intention. Tour. Manag. 2016;54:541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Del Corso J., Rehfuss M.C. The role of narrative in career construction theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011;79(2):334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Geurts S.A.E., Kompier M. Positive and negative work-home interaction: prevalence and correlates. Equal. Oppor. Int. 2004;23(1/2):6–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R., Huntington R., Hutchison S., Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986;71:500–507. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R., Fasolo P., Davis-LaMastro V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990;75:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R.M. Social exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976;2:335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau V., Derqui B., Matute J. The COVID-19 pandemic and organizational commitment of senior hotel managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;91 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N. 2020. How Hotels Are Helping Their Employees Survive the Economic Impact of COVID- 19?https://parkwestgc.com/how-hotels-are-helping-their-employees-survive-the-economic-impact-of-covid-19 June 18, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Frye N.K., Breaugh J.A. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and satisfaction: a test of a conceptual model. J. Bus. Psychol. 2004;19(2):197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin J. 2017. Common Latent Factor: Confirmatory Factory Analysis.http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/index.php?title=Confirmatory_Factor_Analysis&redirect=no#Common_Latent_Factor (Accessed: 27 December 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Ginevra M.C., Magnano P., Lodi E., Annovazzi C., Camussi E., Patrizi P., Nota L. The role of career adaptability and courage on life satisfaction in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2018;62:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Wen Y., Chen S.X., Liu H., Si W., Liu Y., Wang Y., Fu R., Zhang Y., Dong Z. When do salary and job level predict career satisfaction and turnover intention among Chinese managers? The role of perceived organizational career management and career anchor. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014;23(4):596–607. [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Zhou W., Ye L., Jiang P., Zhou Y. Perceived organizational career management and career adaptability as predictors of success and turnover intention among Chinese employees. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015;88:230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Yang W., Zhou X., Tian Z., Eves A. Predicting Chinese human resource managers’ strategic competence: roles of identity, career variety, organizational support and career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016;92:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer T.H., Saksvik P.O., Nytro K., Torvatn H., Bayazit M. Expanding the psychosocial work environment: workplace norms and work-family conflict as correlates of stress and health. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2004;9(1):83–97. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.9.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. The Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: a Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Heath E. 2020. Adaptability May Be Your Most Essential Skill in the Covid-19 World.https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/adaptability-coronavirus-skills/2020/05/26/8bd17522-9c4b-11ea-ad09-8da7ec214672_story.html May 26, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hill E.J. Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. J. Fam. Issues. 2005;26(6):793–819. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter W.A., Ferris G.R., Canty A.L., Frink D.D., Perrewea P.L., Berkson H.M. Reconsidering the job‐performance-turnover relationship: the role of gender in form and magnitude. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001;31(11):2357–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z.J., Leung S.A., Li X., Li X., Xu H. Career adapt-abilities scale - China form: construction and initial validation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012;80(3):686–691. [Google Scholar]

- Ito J.K., Brotheridge C.M. Does supporting employees’ career adaptability lead to commitment, turnover, or both? Hum. Resour. Manage. 2005;44(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. Proactive personality and career adaptability: the role of thriving at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017;98:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jung H.S., Jung Y.S., Yoon H.H. COVID-19: the effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R.A., Triantis K.P., Chaudhry S.S. Coworker and supervisor support as moderators of associations between task characteristics and mental strain. J. Occup. Behav. 1982;3(2):181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M. The effect of positive and negative work‐family interaction on exhaustion. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2010;22(6):836–856. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M. High‐performance work practices, work social support and their effects on job embeddedness and turnover intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2013;25(6):903–921. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M., Bekteshi L. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family facilitation and family-work facilitation among frontline hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008;27(4):517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M., Kilic H. Relationships of supervisor support and conflicts in the work-family interface with the selected job outcomes of frontline employees. Tour. Manag. 2007;28(1):238–252. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M., Olugbade O.A. The effects of work social support and career adaptability on career satisfaction and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Organ. 2017;23(3):337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd J.M., Smewing C. The role of supervisor in career and organizational commitment. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2001;10(1):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw Y.J., Chi N.W., Chuang A. Examining the mechanisms linking transformational leadership, employee customer orientation, and service performance: the mediating roles of perceived supervisor and coworker support. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010;25(3):477–492. [Google Scholar]

- Maertz C.P., Griffeth R.W., Campbell N.S., Allen D.G. The effects of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on employee turnover. J. Organ. Behav. 2007;28:1059–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori C., Johnston C.S., Krings F., Massoudi K., Rossier J. The role of career adaptability and work conditions on general and professional well-being. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013;83(3):437–449. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley S., Mattila A.S. Overcoming job insecurity: examining grit as a predictor. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020;61(2):199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Michel J.W., Kavanagh M.J., Tracey J.B. Got support? The impact of supportive work practices on the perceptions, motivation, and behavior of customer-contact employees. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013;54(2):161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo A.C.G., Reyes M.L., Chen Y., Restubog S.L.D., Chih Y.Y., Chua-Garcia L., Guan P. The role of internship participation and conscientiousness in developing career adaptability: a five-wave growth mixture model analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme M., Zacher H. Job performance ratings: the relative importance of mental ability, conscientiousness, and career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015;87:161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Omar S., Noordin F. Career adaptability and intention to leave among ICT professionals: an exploratory study. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2013;12(4):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannidis S., Marikyan D. Smart offices: a productivity and well-being perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2020 Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman S., Greenhaus J.H., Granrose C.S. Role stressors, social support, and well-being among two-career couples. J. Organ. Behav. 1992;13(4):339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Peng A.C., Zeng W. Workplace ostracism and deviant and helping behaviors: the moderating role of 360 degree feedback. J. Organ. Behav. 2017;38(6):833–855. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos K., Lopez F.G. Attachment security and career adaptability as predictors of subjective well-being among career transitioners. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018;104:72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed M.I., Okumus F., Weng Q., Hameed Z., Nawaz M.S. Career adaptability and employee turnover intentions: the role of perceived career opportunities and orientation to happiness in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020;44:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Roehling M.V., Cavanaugh M.A., Moynihan L.M., Boswell W.R. The nature of the new employment relationship: a content analysis of the practitioner and academic literatures. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2000;39(4):305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rossier J., Zecca G., Stauffer S.D., Maggiori C., Dauwalder J.P. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale in a French-speaking Swiss sample: psychometric properties and relationships to personality and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012;80(3):734–743. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph C.W., Lavigne K.N., Zacher H. Career adaptability: a meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017;98:17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Safavi H.P., Bouzari M. The association of psychological capital, career adaptability and career competency among hotel frontline employees. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 2019;30:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Safavi H.P., Karatepe O.M. High-performance work practices and hotel employee outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2018;30(2):1112–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Saks A.M., Gruman J.A. Getting newcomers engaged: the role of socialization tactics. J. Manag. Psychol. 2011;26(5):383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas M.L. Career adaptability: an integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Dev. Q. 1997;45(3):247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas M.L. In: Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work. Brown S.D., Lent R.W., editors. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. The theory and practice of career construction; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas M.L. In: Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research into Work. 2nd ed. Lent R.W., Brown S.D., editors. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2013. Career construction theory and practice; pp. 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas M.L., Porfeli E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012;80(3):661–673. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas M.L., Nota L., Rossier J., Dauwalder J.P., Duarte M.E., Guichard J., Soresi S., Van Esbroeck R., van Vianen A.E.M. Life designing: a paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009;75:239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Schinoff B.S., Ashforth B.E., Corley K.G. Virtually (in) separable: the centrality of relational cadence in the formation of virtual multiplex relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2020;63(5):1395–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Singh B., Shaffer M.A., Selvarajan T.T. Antecedents of organizational and community embeddedness: the roles of support, psychological safety, and need to belong. J. Organ. Behav. 2018;39(3):339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Storme M., Celik P., Myszkowski N. A forgotten antecedent of career adaptability: a study on the predictive role of within-person variability in personality. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.109936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroh L.K., Brett J.M., Reilly A.H. Family structure, glass ceiling, and traditional explanations for the differential rate of turnover of female and male managers. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996;49(1):99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino L.R., Garcia P.R.J.M., Restubog S.L.D., Bordia P., Tang R.L. Validation of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale and an examination of a model of career adaptation in the Philippine context. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013;83(3):410–418. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino L.R., Garcia P.R.J.M., Lu V.N., Restubog S.L.D., Bordia P., Plewa C. Career adaptation: the relation of adaptability to goal orientation, proactive personality, and career optimism. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014;84(1):39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy P. 2020. Crisis Management Skills: Adaptability.https://www.nationalskillsnetwork.in/adaptability-for-crisis-management-and-to-cope-with-changes April 25, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- van Vianen A.E., Klehe U.C., Koen J., Dries N. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale -Netherlands form: psychometric properties and relationships to ability, personality, and regulatory focus. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012;80(3):716–724. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman R.H., Jr., Waterman J.A., Collard B.A. Toward a career resilient workforce. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1994;72(4):87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne S.J., Shore L.M., Liden R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: a social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997;40:82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Whitener E.M., Walz P.M. Exchange theory determinants of affective and continuance commitment and turnover. J. Vocat. Behav. 1993;42:265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe V., Jayaweera M. Impact of career plateau and supervisory support on career satisfaction. Career Dev. Int. 2010;15(6):544–561. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports - 72.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200401-sitrep-72-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=3dd8971b_2 April 1, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Chen Y., Zhao X.R., Hua N. Transformational leadership, proactive personality and service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2020;32(1):267–287. [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Zheng X. The impact of employee career adaptability: multilevel analysis. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2013;45(6):680–693. [Google Scholar]

- Zacher H. Career adaptability predicts subjective career success above and beyond personality traits and core self-evaluations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014;84(1):21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zacher H. Within-person relationships between daily individual and job characteristics and daily manifestations of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016;92:105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zacher H., Ambiel R.A., Noronha A.P.P. Career adaptability and career entrenchment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015;88:164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Yang W. Consumers’ responses to invitations to write online reviews. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2019;31(4):1609–1625. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Guo L. The trickle-down effects of creative work involvement: the joint moderating effects of proactive personality and leader creativity expectations. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019;142:218–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F., Cai Z., Buchtel E.E., Guan Y. Career construction in social exchange: a dual-path model linking career adaptability to turnover intention. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019;112:282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang W.L., Chen K.Y., Chang C.L., Guan X., Huan T.C. Effect of hotel employees’ workplace friendship on workplace deviance behaviour: moderating role of organisational identification. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;88 Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.