Abstract

Infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been linked to approximately 10%–15% of lymphomas diagnosed in the USA, including a small percentage of Natural Killer (NK)/T cell lymphomas, which are clinically aggressive, respond poorly to chemotherapy and have a shorter survival. Here, we present a case of a patient found to have EBV-induced NK/T cell lymphoma from a chronic EBV infection. While the EBV most commonly infects B cells, it can infect NK/T cells, and it is important for the clinician to be aware of the potential transformation to lymphoma as it is clinically aggressive, warranting early recognition and treatment. NK/T cell lymphoma is a unique type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that is almost always associated with EBV. The disease predominantly localises in the upper aerodigestive tract, most commonly in the nose.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, head and neck surgery

Background

Infection with Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) has been linked to approximately 10%–15% of lymphomas diagnosed in the USA, which is a smaller percentage when compared with East Asia and Latin America.1 Included in this spectrum of neoplasms, to a lesser degree than B cell lymphomas, the EBV has been associated with mature NK/T cell lymphomas, which are known to be clinically aggressive, respond poorly to chemotherapy and have a much shorter survival.1 According to the WHO classification, these NK/T cell lymphomas include NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type, aggressive NK cell leukaemia, peripheral T cell lymphoma, systemic T cell lymphoma of childhood and chronic active EBV (CAEBV) infection.2 3 While the mechanism behind the transformation of memory B cells to neoplastic cells appears to be well understood, the pathogenesis of lymphomas is still unclear in EBV-infected T cells and NK cells.1 Herein, we present a case of a patient found to have EBV-induced NK/T cell lymphoma from a chronic EBV infection.

Case presentation

The patient is a 27-year-old man, who presented with a 2-year history of throat pain, thought to be caused by chronic EBV.

In 2016, while in Ecuador, he had noted throat pain and tonsillar swelling, for which he was started on steroids and anti-inflammatories for presumed tonsilitis, which improved his symptoms. Two years later, after arriving from Ecuador, the patient had noticed that the throat pain had recurred, at which time he went to an otolaryngologist, who repeated a steroid course, for presumed recurrent tonsilitis, which resolved his symptoms. He continued to have recurrent throat pain and swelling, and so, in 2018, he presented to a different otolaryngologist, and he underwent a tonsillectomy for these recurrent infections, now associated with dysphagia. Pathology from his tonsillectomy revealed reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Four months later, the patient had noted that he had a painful left neck mass, with associated intermittent fevers. Initially treated as an infection with antibiotics, he continued to have recurrent symptoms, and he eventually was re-evaluated, and on imaging was found to have a 3×3×2 cm mass.

Investigations

Given the new findings of a left neck mass, a fine-needle aspiration was performed, which on histopathologic review, revealed a lymphoproliferative process, however, the sample was not sufficient enough to exclude other malignant process as the cause of his recurrent symptoms. Of note, the authors do not have access to the pathological slides of the fine-needle aspiration. He additionally underwent testing for HIV which was negative. Given his recurrent symptoms, he was taken to the operating room and underwent resection of the left neck mass. The final histopathology showed parafollicular hyperplasia with zonal necrosis, with scattered Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg-like cells, which were strongly positive for EBV on in situ hybridisation (figures 1–4). Additional testing of the lymph node was negative for acid fast bacilli, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus. Postoperatively, he had persistent fevers, night sweats and weight loss, and was referred to a haematologist–oncologist for further management. The biopsies were eventually sent to the National Institute of Health, at which time it was determined that his lymph node pathology was NK/T cell lymphoma, indicative of a diagnosis of EBV-induced NK/T cell lymphoma. Additionally, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, given his cytopaenias, which was consistent with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) secondary to NK/T cell lymphoma. He was admitted in January of 2019 for worsening cough, neck pain, persistent fevers and fatigue. On admission, he was noted to have worsening pancytopaenia.

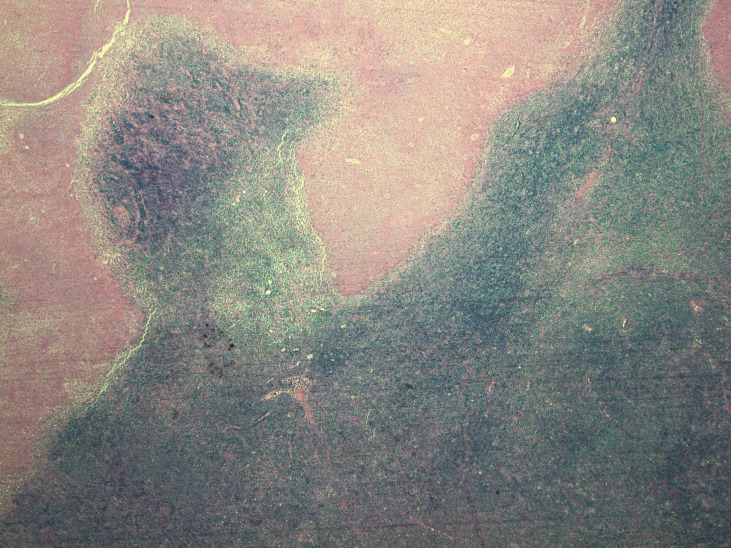

Figure 1.

The enlarged lymph node architecture is completely effaced by parafollicular hyperplasia (4×).

Figure 2.

The lymph node shows focal geographic necrosis (4×).

Figure 3.

High-power magnification of parafollicular area shows a range of predominantly small to medium-sized lymphoid cells with scattered large lymphoid cells (40×).

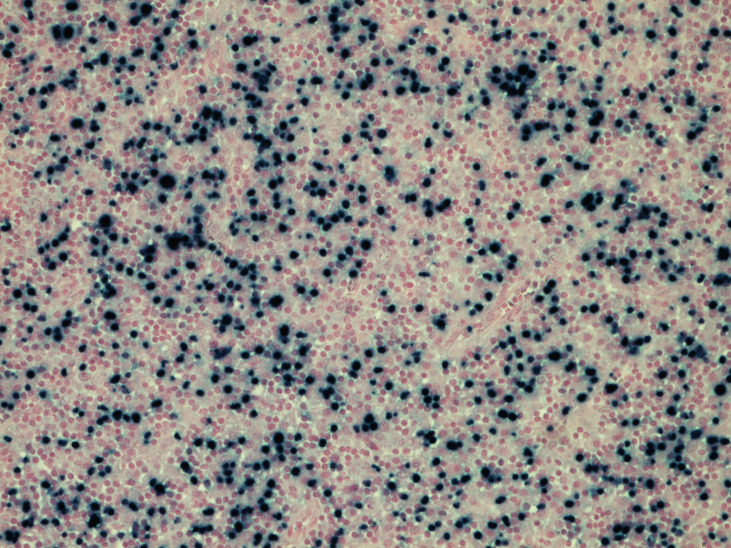

Figure 4.

In situ hybridisation for EBV small encoded RNA shows numerous positive cells (20×).

Treatment

He was started on SMILE regimen, which generally consists of dexamethasone, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase and etoposide.4 However, methotrexate and L-asparaginase could not be given as the patient had poor liver function and was therefore continued on etoposide and steroids. However, over the course of his hospital stay, he continued to clinically worsen. After discussion with several other haematologists and oncologists, he was started on anakinra. The patient continued to have neutropaenia, and complete infectious workup, including blood and urine cultures, fungal cultures, respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus were negative. He eventually developed renal failure, with severe metabolic acidosis, and was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU). While in the SICU, he continued with his SMILE regimen, and was urgently started on haemodialysis for acute renal failure with severe metabolic acidosis and oliguria.

Outcome and follow-up

While in the ICU, he deteriorated into multiorgan system failure. He was intubated and required pressor support. In addition to renal failure, he continued to have worsening liver function tests. A meeting was held with the family to discuss whether to use the medication emapalumab. The medication had just been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for primary HLH and had a discussion with the family regarding using it for his secondary HLH. Given the lack of data at the time supporting its use in secondary HLH and the patient’s decompensation, the family elected to focus on patient comfort and the patient expired.

Discussion

The EBV naturally infects the B cell lineage and does not generally infect the T cells and NK cells, except on rare occasions, which generally present as CAEBV.5 CAEBV infections generally present with persistent or recurrent infectious mononucleosis symptoms, such as fever, haepatosplenomegaly, elevated liver transaminases, as well as lymphadenopathy.5 6 The infectivity of EBV on B cells is well documented, and is more commonly associated with infections of B cells, however, it can infect the NK/T cells. Despite its effect on B cells being well known, the mechanism by which these NK/T cells are infected is not as well established.1 It appears that the EBV does directly infect NK or T cells, leading to proliferation of the virus and the NK and T cells, which leads to the release of immune inflammatory factors interleukin and interferon.6

The first report of the transformation of EBV infection into NK/T cell lymphoma was seen in two patients who suffered from CAEBV infection who later developed T cell lymphoma.1 This association of EBV with NK/T lymphomas is more common in the East Asia population, while EBV is more commonly seen with B cell lymphomas in the USA.1 Extranodal involvement of NK/T cell lymphomas are more commonly seen in the young and middle-aged patient populations, and regardless of the patient’s age, and this feature, portends poor outcomes.3 In contrast, nodal NK/T cell lymphomas, such as that seen in our patient, are rare and more commonly affect the elderly population.3 In a case series of 15 patients with EBV associated nodal NK/T cell lymphomas, most patients were noted to have multisystem involvement, including the spleen and liver.3 The patients’ clinical course analysed in this study had minimal response to chemotherapy, and 80% of the patients died from the disease and the associated systemic complications, with a median survival of less than 4 months.3

There is also an increased risk of developing HLH with lymphoma, particularly NK/T cell lymphoma. Indeed the most common cause of acquired HLH is due to T cell, particularly NK/T cell lymphomas.7 Increased histiocytes and increased haemophagocytic activity may be seen on biopsy as with our patient’s bone marrow. Additionally this inflammatory condition can commonly present with cytopaenias, fever and elevated liver function tests. The diagnosis of HLH incorporates the presence of at least five of the HLH criteria, which includes prolonged fever, thrombocytopaenias, splenomegaly, hypertriglycerdia or decreased fibrinogen, increased ferritin, high CD25, evidence of haemophagocytosis, now or absent NK cell function, of which our patient had seven.8 Therapy for secondary HLH involves treating the underlying cause of the lymphoma. HLH secondary to NK/T cell lymphoma can be quite lethal, with mortality as high as 96% and median survival 15 days from the onset of HLH.9

Learning points.

Be aware of the rare but highly virulent transformation of Epstein-Barr virus into B cell lymphoma or natural killer/T cell lymphoma.

Careful monitoring for this transformation if a patient remains or becomes symptomatic, despite removal of the node or tonsillar tissue.

If haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis develops in the setting of lymphoma, the clinical picture can rapidly deteriorate, and expeditious initiation of chemotherapy is crucial.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the research regarding the EBV and its association with NK/T cell lymphoma. ATS was the main reporter of the clinical course of the patient. JT provided analysis of the pathologic slides described in the paper. AS provided the pathologic images and interpretations, as well as information regarding the diagnosis and treatment of patients with this disease process. LS was the main coordinator between the three authors in gathering data and pathologic images as well as the main editor of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Gru AA, Haverkos BH, Freud AG, et al. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in T cell and NK cell lymphomas: time for a reassessment. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2015;10:456–67. 10.1007/s11899-015-0292-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takada H, Imadome K-I, Shibayama H, et al. Ebv induces persistent NF-κB activation and contributes to survival of EBV-positive neoplastic T- or NK-cells. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174136. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon YK, Kim J-H, Sung J-Y, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive nodal T/NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of 15 cases with distinct clinicopathological features. Hum Pathol 2015;46:981–90. 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi M, Kwong Y-L, Kim WS, et al. Phase II study of SMILE chemotherapy for newly diagnosed stage IV, relapsed, or refractory extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: the NK-Cell Tumor Study Group study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4410–6. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shannon-Lowe C, Rickinson AB, Bell AI. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017;372:20160271. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y-D, Wu L-L, Ma L-Y, et al. Chronic active EBV infection associated with NK cell lymphoma and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a 27-year-old woman: a case report. Medicine 2019;98:e14032. 10.1097/MD.0000000000014032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han A-R, Lee HR, Park B-B, et al. Lymphoma-Associated hemophagocytic syndrome: clinical features and treatment outcome. Ann Hematol 2007;86:493–8. 10.1007/s00277-007-0278-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henter J-I, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. 10.1002/pbc.21039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y-Z, Bi L-Q, Chang G-L, et al. Clinical characteristics of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cancer Manag Res 2019;11:997–1002. 10.2147/CMAR.S183784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]