Key Points

Question

Was the reversal of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guideline discouraging prostate cancer screening associated with rates of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing?

Findings

In this large, national cohort study of privately insured patients (mean bimonthy cohort size of 8 087 565), there was a 12.5% relative increase in rates of PSA testing for men aged 40 to 89 years from 2016 to 2019. Significant increases were seen among patients aged 55 to 69 years, for whom screening is specified by the guideline, but also among those aged 40 to 54 years and those aged 70 years or older, for whom screening is not recommended.

Meaning

Rates of PSA testing increased significantly after the USPSTF’s 2017 draft statement on prostate cancer screening, reversing trends that resulted from earlier guidance.

Abstract

Importance

In April 2017, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a draft guideline that reversed its 2012 guidance advising against prostate-specific antigen (PSA)–based screening for prostate cancer in all men (grade D), instead endorsing individual decision-making for men aged 55 to 69 years (grade C).

Objective

To evaluate changes in rates of PSA testing after revisions in the USPSTF guideline on prostate cancer screening.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used deidentified claims data from Blue Cross Blue Shield beneficiaries aged 40 to 89 years from January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2019.

Exposures

Publication of the USPSTF’s draft (April 2017) and final (May 2018) recommendation on prostate cancer screening.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Age-adjusted rates of PSA testing in bimonthly periods were calculated, and PSA testing rates from calendar years before (January 1 to December 31, 2016) and after (January 1 to December 31, 2019) the guideline change were compared. Interrupted time series analyses were used to evaluate the association of the draft (April 2017) and published (May 2018) USPSTF guideline with rates of PSA testing. Changes in rates of PSA testing were further evaluated among beneficiaries within the age categories reflected in the guideline: 40 to 54 years, 55 to 69 years, and 70 to 89 years.

Results

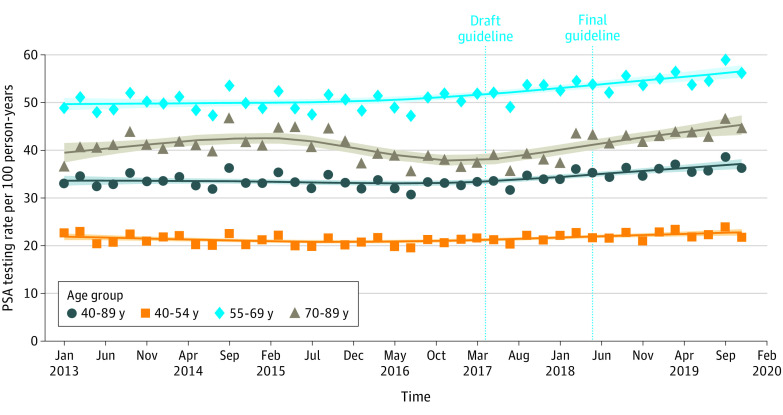

The median number of eligible beneficiaries for each bimonthly period was 8 087 565 (range, 6 407 602-8 747 308), and the median age of all included eligible beneficiaries was 53 years (IQR, 47-59 years). Between 2016 and 2019, the mean (SD) rate of PSA testing increased from 32.5 (1.1) to 36.5 (1.1) tests per 100 person-years, a relative increase of 12.5% (95% CI, 1.1%-24.4%). During the same period, mean (SD) rates of PSA testing increased from 20.6 (0.8) to 22.7 (0.9) tests per 100 person-years among men aged 40 to 54 years (relative increase, 10.1%; 95% CI, −2.8% to 23.7%), from 49.8 (1.9) to 55.8 (1.8) tests per 100 person-years among men aged 55 to 69 years (relative increase, 12.1%; 95% CI, −0.2% to 25.2%), and from 38.0 (1.4) to 44.2 (1.4) tests per 100 person-years among men aged 70 to 89 years (relative increase, 16.2%; 95% CI, 4.2%-29.0%). Interrupted time series analysis revealed a significantly increasing trend of PSA testing after April 2017 among all beneficiaries (0.30 tests per 100 person-years for each bimonthly period; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This large national cohort study found that rates of PSA testing increased after the USPSTF’s draft statement in 2017, reversing trends seen after earlier guidance against PSA testing for all patients. Increased testing was also observed among older men, who may be less likely to benefit from prostate cancer screening.

This cohort study uses deidentified claims data from Blue Cross Blue Shield beneficiaries aged 40 to 89 years to evaluate changes in rates of prostate-specific antigen testing after the 2017 revision of the US Preventive Services Task Force guideline on prostate cancer screening.

Introduction

The effects of recent conflicting guidance on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer during the past decade are not yet fully understood. In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued a grade D recommendation against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer.1,2 At the time, the guideline expressed moderate to high certainty that the harms of PSA screening outweighed the benefits.3,4 In the subsequent period, the guideline was rapidly incorporated into practice, and there have been measurable decreases in rates of PSA testing and diagnostic biopsies, as well as the number of prostate cancers identified in the United States.5,6,7 There are also increasing concerns that reductions in PSA testing associated with the USPSTF statement were temporally associated with increases in the incidence of prostate cancers diagnosed at an advanced or metastatic stage.8,9

In April 2017, the USPSTF published a draft guideline that reversed prior guidance against routine screening for prostate cancer, issuing a grade C recommendation for men aged 55 to 69 years that the decision to undergo periodic PSA-based screening for prostate cancer should be an individual one, based on a discussion of the potential benefits and harms. The updated guideline was published in its final form in May 2018 and continued to emphasize the potential harms of screening and to discourage PSA testing for patients 70 years or older.10 Changes to the guideline were, in part, attributed to the availability of new evidence, including extended follow-up of a European randomized screening trial that identified a substantial reduction in the risk of prostate cancer mortality associated with PSA screening.11 To date, the effects of recent shifts in USPSTF guidance on national rates of PSA testing are not known but have important public health implications. There are increasing concerns that migration toward detection of later-stage disease will erode decades of improvement in prostate cancer mortality, and it is unclear whether updates in recommendations have reversed these trends.12,13 Conflicting recommendations may have also increased existing high levels of public uncertainty about PSA testing, potentially minimizing the effect of further guideline changes.14

We assessed the association between the recent changes in the USPSTF guideline to a grade C recommendation and national rates of PSA testing among a large population of privately insured men in the US. We sought to identify patterns of testing in the age group specified in the guideline (55-69 years) as well as among those for whom screening remains without recommendation (40-54 years) or discouraged (≥70 years) by the USPSTF guideline.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort Selection

We conducted a retrospective study using Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) Axis, an administrative claims database comprising 36 individual health organizations and companies providing care to approximately one-third of all individuals in the US. We accessed deidentified claims data for BCBS beneficiaries. We categorized the time from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2019, into 42 consecutive, independent 2-month periods. For each period, we included male beneficiaries who were aged 40 to 89 years at the beginning of each period and had continuous insurance coverage for at least 14 months (12 months before the period of interest to the end of the period of interest). Patients with a history of prostate cancer by diagnosis code were censored before the month of first prostate cancer diagnosis. This study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board, which deemed the study to be nonhuman participants research, and therefore no informed consent was required. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Screening recommendations for prostate cancer are age specific. Therefore, we examined trends in PSA testing among patients aged 40 to 89 years as well as by age thresholds defined in the USPSTF statements (ie, 40-54, 55-69, and 70-89 years).10 We further examined screening patterns within 5-year categories among beneficiaries between 40 and 89 years of age.

Statistical Analysis

We compiled crude counts of PSA tests performed and assessed the testing status for each patient within each bimonthly period. Using the US 2000 standard population (single ages),15 we calculated age-adjusted rates of PSA testing per 100 person-years. We calculated the absolute and relative change in PSA testing rates, as well as the 95% CIs, in 2 complete calendar years that preceded (2016) and followed (2019) the changes in the USPSTF screening guideline for prostate cancer.16 In addition, we used interrupted time series analysis, a design that has been widely used to examine the effects of large-scale policy interventions implemented at discrete time points,17 including prior evaluations of the USPSTF’s screening guidelines.7,18 Based on prior evidence that changes in PSA testing rates occurred without significant lag after highly publicized guideline changes, we proposed an impact model that assumed immediate effects.7 We hypothesized that 2 events might have been associated with the rates of PSA screening in the study period: the publications of the USPSTF’s draft (April 2017) and final guideline (May 2018) on prostate cancer screening. We first graphically depicted the trend of age-adjusted PSA rates using a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing function.19 Based on the observed trend (Figure), we selected April 2017, the date of the release of the draft guideline, as a node for 2 segments of the line; these periods include 26 bimonthly time points before the guideline change and 16 monthly time points after the guideline change.

Figure. Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Testing Rates Among Commercially Insured Patients Relative to the April 2017 Publication of US Preventive Services Task Force Draft Guideline That Reversed Prior Guidance Against PSA Testing.

The symbols indicate the observed bimonthly testing rates.

We fit segmented regression to the series of bimonthly testing rates, with parameters for intercept, baseline trend, and changes in level and trend after the release of the draft guideline, assuming linearity of the trend lines within each segment. Dickey-Fuller unit root tests revealed that bimonthly rates of PSA testing had no unit root and were stationary over time.20 We tested for up to 6-order autocorrelation using the Durbin-Watson statistic, which indicated no evidence of autocorrelation. In addition, we performed a sensitivity analysis among the subset of patients without evidence of PSA testing within the preceding 12-month period. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

The median number of eligible beneficiaries for each bimonthly period was 8 087 565 (range, 6 407 602-8 747 308). Within each period, nearly half of the eligible beneficiaries were aged 40 to 54 years (median, 56.5%; range, 54.0%-60.7%). The median bimonthly number of eligible beneficiaries in the group aged 55 to 69 years was 3 372 772 (range, 2 419 457-3 816 257), and the median bimonthly number of eligible beneficiaries in the group aged 70 to 89 years was 148 195 (range, 97 398-184 978). The median age of all included eligible beneficiaries was 53 years (IQR, 47-59 years). Patients who received PSA testing were older than patients without evidence of PSA testing (median age, 57 years [IQR, 52-61 years] vs 53 years [IQR, 46-59 years]). The age difference between beneficiaries with and beneficiaries without PSA testing was consistent across the 42 bimonthly periods.

Among patients aged 40 to 89 years, the mean (SD) rate of PSA testing increased from 32.5 (1.1) per 100 person-years in 2016 to 36.5 (1.1) per 100 person-years in 2019 (P < .001) (Table 1). The difference in testing rates corresponds to a 4.0% absolute increase (95% CI, 1.5%-6.6%), and a 12.5% (95% CI, 1.1%-24.4%) relative increase. Interrupted time series analysis revealed a significant increase in PSA testing after the publication of the draft guideline in April 2017 (0.30 tests per 100 person-years for each bimonthly period after the guideline change; P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 1. Changes in PSA Testing Rates Among Beneficiaries in the Calendar Year Preceding Publication of Revised USPSTF Draft Statement on PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer Relative to Calendar Year 2019.

| USPSTF age category | Mean (SD) PSA testing rate per 100 person-years | P value | Absolute change (95% CI), % | Relative change (95% CI), % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preperiod (January to December 2016) | Postperiod (January to December 2019) | ||||

| Age group, 40-89 y | 32.5 (1.1) | 36.5 (1.1) | <.001 | 4.0 (1.5 to 6.6) | 12.5 (1.1 to 24.4) |

| Age group, 40-54 y | 20.6 (0.8) | 22.7 (0.9) | .001 | 2.1 (0.2 to 3.9) | 10.1 (−2.8 to 23.7) |

| 40-44 | 11.2 (0.5) | 11.7 (0.5) | .10 | 0.6 (−0.6 to 1.7) | 4.9 (−9.9 to 20.8) |

| 45-49 | 18.3 (0.7) | 19.7 (0.9) | .01 | 1.4 (−0.4 to 3.2) | 7.8 (−6.2 to 22.6) |

| 50-54 | 35.5 (1.3) | 40.4 (1.4) | <.001 | 4.8 (1.8 to 7.8) | 13.5 (1.2 to 26.6) |

| Age group, 55-69 y | 49.8 (1.9) | 55.8 (1.8) | <.001 | 6.0 (1.9 to 10.2) | 12.1 (−0.2 to 25.2) |

| 55-59 | 43.4 (1.6) | 49.2 (1.6) | <.001 | 5.9 (2.2 to 9.5) | 13.5 (1.2 to 26.5) |

| 60-64 | 53.0 (2.2) | 59.5 (2.0) | <.001 | 6.5 (1.8 to 11.2) | 12.3 (−0.8 to 26.2) |

| 65-69 | 55.3 (2.1) | 61.1 (2.0) | <.001 | 5.8 (1.2 to 10.4) | 10.5 (−1.6 to 23.3) |

| Age group, 70-89 y | 38.0 (1.4) | 44.2 (1.4) | <.001 | 6.2 (3.1 to 9.2) | 16.2 (4.2 to 29.0) |

| 70-74 | 50.0 (1.7) | 58.3 (1.9) | <.001 | 8.2 (4.2 to 12.3) | 16.5 (4.3 to 29.2) |

| 75-79 | 39.1 (1.8) | 45.3 (1.9) | <.001 | 6.2 (2.1 to 10.3) | 15.9 (0.3 to 32.6) |

| 80-84 | 25.6 (1.0) | 30.6 (1.0) | <.001 | 5.0 (2.7 to 7.3) | 19.7 (6.1 to 34.1) |

| 85-89 | 18.5 (1.1) | 19.9 (1.0) | .04 | 1.4 (−0.9 to 3.7) | 7.7 (−9.9 to 26.9) |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

Table 2. Results of Interrupted Time Series Models Examining Changes in Rates of PSA Testing Relative to Publication of USPSTF Draft Statement on PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer in April 2017.

| Variable | All eligible beneficiaries receiving PSA screening | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | P value | |

| Age group, 40-89 y | ||

| Intercept | 33.9 (0.47) | <.001 |

| Time (bimonthly) | −0.042 (0.03) | .18 |

| Guideline | 0.25 (0.75) | .75 |

| Additional bimonthly period postdraft guideline | 0.30 (0.07) | <.001 |

| Age group, 40-54 y | ||

| Intercept | 21.7 (0.35) | <.001 |

| Time (bimonthly) | −0.05 (0.02) | .05 |

| Guideline | 0.67 (0.57) | .25 |

| Additional bimonthly period postdraft guideline | 0.15 (0.05) | .006 |

| Age group, 55-69 y | ||

| Intercept | 49.6 (0.68) | <.001 |

| Time (bimonthly) | 0.03 (0.04) | .49 |

| Guideline | 0.81 (1.09) | .46 |

| Additional bimonthly period postdraft guideline | 0.31 (0.10) | .004 |

| Age group, 70-89 y | ||

| Intercept | 42.4 (0.96) | <.001 |

| Time (bimonthly) | −0.13 (0.06) | .04 |

| Guideline | −1.60 (1.54) | .31 |

| Additional bimonthly period postdraft guideline | 0.65 (0.14) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

Among beneficiaries aged 55 to 69 years, the mean (SD) overall rate of PSA testing increased from 49.8 (1.9) per 100 person-years in 2016 to 55.8 (1.8) per 100 person-years in 2019 (P < .001) (Table 1). The difference corresponds to a 6.0% (95% CI, 1.9%-10.2%) absolute increase in testing and a 12.1% (95% CI, −0.2% to 25.2%) relative increase in testing. In this age group, interrupted time series analysis revealed a significant increase in PSA testing after April 2017 (0.31 additional tests per 100 person-years in each successive bimonthly period; P = .004) (Table 2).

Rates of PSA testing increased among beneficiaries outside of the age categories recommended by the revised guideline. Among men aged 40 to 54 years, the mean (SD) overall rates of testing increased from 20.6 (0.8) per 100 person-years in 2016 to 22.7 (0.9) per 100 person-years in 2019 (P = .001), a 2.1% (95% CI, 0.2%-3.9%) absolute increase and 10.1% (95% CI, −2.8% to 23.7%) relative increase (Table 1). There was a trend of increasing PSA testing among this group after April 2017 (0.15 additional tests per 100 person-years in successive bimonthly periods after guideline change; P = .006) (Table 2). For the subset of patients aged 70 to 89 years, mean (SD) rates of testing increased from 38.0 (1.4) per 100 person-years in 2016 to 44.2 (1.4) per 100 person-years in 2019 (P < .001) (Table 1). These correspond to a 6.2% (95% CI, 3.1%-9.2%) absolute increase and 16.2% (95% CI, 4.2%-29.0%) relative increase in PSA testing rate. The largest absolute change was seen among those aged 70 to 74 years (from a mean [SD] of 50.0 [1.7] per 100 person-years in 2016 to 58.3 [1.9] per 100 person-years in 2019, for an absolute increase of 8.2% [95% CI, 4.2%-12.3%]; P < .001); however, significant relative increases were observed for all subsets of patients aged 70 years or older.

Interrupted time series analysis revealed a significant trend for the subset of patients aged 70 to 89 years (0.65 tests per 100 person-years in successive bimonthly periods; P < .001) (Table 2). Similar trends of increasing PSA testing after the guideline change were observed for the subsets of patients aged 70 to 74 years (bimonthly increase in PSA testing rate, 0.62 per 100 person-years; P < .001), aged 75 to 79 years (bimonthly increase in PSA testing rate, 0.70 per 100 person-years; P < .001), and aged 80 to 84 years (bimonthly increase in PSA testing rate, 0.62 per 100 person-years; P = .02). There were no significant time-associated increases in the PSA testing rate among men aged 85 to 89 years. Sensitivity analyses revealed that rates of PSA testing also increased among patients without prior screening in the preceding 12-month period, although the magnitude of changes was smaller (eTable in the Supplement).

Discussion

Rates of PSA testing among privately insured men increased after changes in 2017 to the USPSTF’s prostate cancer screening guideline that elevated PSA screening for prostate cancer from a grade D to grade C recommendation. After the change, the rate of PSA testing increased by 12.1% among men aged 55 to 69 years, the age category targeted by the revised guideline. However, increases were also observed among men aged 40 to 54 years and those older than 70 years, age groups for whom screening is not recommended or is discouraged by the USPSTF owing to lower levels of supporting evidence. In light of concerns that decreases in PSA testing associated with 2012 USPSTF guidance have catalyzed increases in diagnoses of advanced prostate cancer, these findings provide, to our knowledge, the first indication that PSA testing has increased.7,12,21 Increasing rates of PSA testing in age groups for whom screening remains explicitly discouraged highlights the need to enhance the quality of decision-making for early detection of prostate cancer given downstream consequences, such as unnecessary biopsy and the overdetection of low-grade disease.22

Increasing rates of PSA testing associated with a 2017 draft statement exist in the context of sharp decreases in testing that followed the previous 2012 guidance that discouraged screening. We found that changes in PSA testing were implemented rapidly and were temporally associated with the publication of the draft guideline more so than with the final version published more than 1 year later. Similar patterns of prompt decreases in testing were seen after the draft publication of the grade D recommendation in 2011, indicating continued responsiveness to subsequent changes.6,7,9 Considerable early increases in PSA testing likely reflected high levels of awareness that have been amplified by media attention and controversies surrounding the USPSTF recommendations.23,24 In the intervening years leading up to the 2017 draft statement, a range of prostate cancer stakeholders, including advocacy groups, politicians, and celebrities, continued to encourage screening.25,26 Responsiveness may also be associated with greater connectivity within the medical community through online social media, forums through which changes to USPSTF guidelines have been actively discussed.27

Although PSA screening increased in the target age category specified by the updated guideline, there was also pronounced uptake of screening among both younger and older patients. Increases in testing were expected in the demographic category of men aged 55 to 69 years to whom the guideline change directly pertained. However, the guideline maintained a grade D (“do not screen”) recommendation for testing in men aged 70 years or older and did not discuss the role of PSA screening for men younger than 55 years. Increases in PSA screening for these age groups suggest the need to reinforce decision-making about the potential benefits and harms as stipulated by the guideline, rather than reviving the use of PSA testing as a routine component of health maintenance. Increased screening among younger patients may also reflect emerging evidence about the prognostic value of the patient’s baseline PSA level at middle age.28 Further study is needed to understand patient perspectives and potential quality-of-life outcomes associated with screening younger men. These results should also strengthen efforts to align PSA testing with best practice, particularly for those least likely to benefit, such as men older than 75 years or those with significant medical comorbidity.21

The consequences of increased PSA testing remain to be appreciated. Decreases in PSA testing that followed the 2012 USPSTF grade D recommendation have been associated with increasing proportions of higher-stage disease and increasing incidence of metastatic disease, although a causal relationship has not been established.12 Based on the protracted natural history of prostate cancer, additional years of follow-up are needed to detect changes in advanced-stage disease and prostate cancer mortality. In the near term, research efforts can focus on intermediary outcomes, such as cancer grade, stage, and the use of definitive treatment as they relate to increased screening.

Increases in PSA testing offer an opportunity to promote evidence-based practices that can further shift the balance of risks and benefits for patients considering prostate cancer screening. The persistence of overly simplistic diagnostic pathways (such as biopsy for men whose PSA level is above a single PSA cutoff value) will be poised to expose more patients to the potential harms of prostate biopsy and the overdetection of indolent prostate cancer.18,29,30 In the decade after the USPSTF’s grade D recommendation, a host of refinements to the diagnostic algorithm have emerged, including risk calculators, prebiopsy biomarkers, and polygenic risk scores, all of which appear to reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies performed and indolent cancers detected without meaningfully compromising the detection of potentially lethal cancers.31,32,33 Although their promise has been touted, these strategies have not met yet widespread adoption as biopsy mitigation strategies in the US. Practice guidelines and payors should therefore go further by offering clearer parameters for their use, as well as consistent reimbursement given anticipated cost-effectiveness.34 At the same time, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also transformed the diagnosis of prostate cancer by improving detection of significant tumors.35 Triage strategies involving selective biopsy of areas considered suspicious on MRI scans may further reduce the use of biopsy and indolent cancer detection, yet combined systematic biopsy remains a standard practice in the US and may perpetuate problems of overdetection.36,37 Embracing an MRI-centered approach to biopsy selection, as has been accepted in several countries, would be a significant step to enhance the detection of potentially lethal cancers while also stemming the burden of unnecessary biopsy.38,39,40

Limitations

There are limitations to this analysis. We did not examine changes in associated diagnostic procedures, incident prostate cancer cases, or stage at diagnosis. However, prior analyses have shown that rates of associated interventions and cancer diagnosis closely parallel rates of PSA testing.7 In addition, although BCBS is the largest source of commercial health care claims, it may not reflect all populations because it is skewed toward younger and more socioeconomically advantaged patients with employment-based insurance. The median age of beneficiaries was 53 years (IQR, 47-59 years), and there was a relatively smaller number of patients aged 70 years or older. However, patterns of PSA testing among privately insured patients have previously mirrored those found in population-based registries,7 and our sample sizes for the subgroup of men aged 70 years or older remained substantial in all periods. Based on the anonymized nature of the administrative claims, we were unable to assess patients’ race or family history. Although the 2018 guideline noted that African American men face higher risks of prostate cancer, the USPSTF did not make specific recommendations by race. Therefore, additional study in complementary data sources is needed to assess whether PSA testing differed by race or other sociodemographic factors. Based on the nature of administrative claims, we were not able to account for the existence or quality of shared decision-making associated with PSA testing, conditions specified by the updated guideline. Last, 2019 was the most recent year for which we have access to BCBS data, so this analysis does not take into account the likely substantial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on rates of cancer screening, including PSA testing.41 It remains to be determined whether rates of screening will return to prior levels.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge this work is the first to evaluate changes in PSA testing after updates to the USPSTF guideline on prostate cancer screening. By identifying appreciable early increases in PSA testing rates, this work can directly inform estimates of the outcome of the USPSTF statement change, signaling a reversal in early detection practices. The findings of increased screening outside of target age categories, including those for whom screening remains discouraged by the task force and other clinical guidelines, can again focus efforts to improve the quality of prostate cancer screening.

Conclusions

This large national cohort study found that rates of PSA testing increased after changes to the USPSTF’s draft statement in 2017, reversing trends seen after earlier guidance against PSA testing for all patients. A significant increase in testing was observed among patients aged 55 to 69 years, the age group specified in the USPSTF guideline, but significant increasing trends were also observed among men aged 40 to 54 years and 70 to 89 years.

eTable. Results of Sensitivity Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Changes in Rates of PSA Testing Relative to Publication of USPSTF Draft Statement on PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer Among Patients Without Evidence of PSA Testing the Preceding 12-Month Period

References

- 1.Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(2):120-134. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slomski A. USPSTF finds little evidence to support advising PSA screening in any man. JAMA. 2011;306(23):2549-2551. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):762-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barocas DA, Mallin K, Graves AJ, et al. Effect of the USPSTF grade D recommendation against screening for prostate cancer on incident prostate cancer diagnoses in the United States. J Urol. 2015;194(6):1587-1593. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker DJ, Rude T, Walter D, et al. The association of veterans’ PSA screening rates with changes in USPSTF recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(5):626-631. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frendl DM, Epstein MM, Fouayzi H, Krajenta R, Rybicki BA, Sokoloff MH. Prostate-specific antigen testing after the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation: a population-based analysis of electronic health data. Cancer Causes Control. 2020;31(9):861-867. doi: 10.1007/s10552-020-01324-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearns JT, Holt SK, Wright JL, Lin DW, Lange PH, Gore JL. PSA screening, prostate biopsy, and treatment of prostate cancer in the years surrounding the USPSTF recommendation against prostate cancer screening. Cancer. 2018;124(13):2733-2739. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kensler KH, Pernar CH, Mahal BA, et al. Racial and ethnic variation in PSA testing and prostate cancer incidence following the 2012 USPSTF recommendation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):719-726. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Fedewa SA, Ma J, et al. Prostate cancer incidence and PSA testing patterns in relation to USPSTF screening recommendations. JAMA. 2015;314(19):2054-2061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.14905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901-1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ; ERSPC Investigators . Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2027-2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler SS, Muralidhar V, Zhao SG, et al. Prostate cancer incidence across stage, NCCN risk groups, and age before and after USPSTF grade D recommendations against prostate-specific antigen screening in 2012. Cancer. 2020;126(4):717-724. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Presti J Jr, Alexeeff S, Horton B, Prausnitz S, Avins AL. Changes in prostate cancer presentation following the 2012 USPSTF screening statement: observational study in a multispecialty group practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1368-1374. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05561-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partin MR, Lillie SE, White KM, et al. Similar perspectives on prostate cancer screening value and new guidelines across patient demographic and PSA level subgroups: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):779-787. doi: 10.1111/hex.12517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute; Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Standard population—single ages. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/stdpop.singleages.html

- 16.Kohavi R, Longbotham R, Sommerfield D, Henne RM. Controlled experiments on the web: survey and practical guide. Data Min Knowl Discov. 2009;18(1):140-181. doi: 10.1007/s10618-008-0114-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershman B, Van Houten HK, Herrin J, et al. Impact of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening trials and revised PSA screening guidelines on rates of prostate biopsy and postbiopsy complications. Eur Urol. 2017;71(1):55-65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleveland WS. LOWESS: a program for smoothing scatterplots by robust locally weighted regression. Am Statistician. 1981;35(1):54. doi: 10.2307/2683591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74(366):427-431. doi: 10.2307/2286348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Neil B, Martin C, Kapron A, Flynn M, Kawamoto K, Cooney KA. Defining low-value PSA testing in a large retrospective cohort: finding common ground between discordant guidelines. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;56:112-117. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. ; CAP Trial Group . Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: the CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(9):883-895. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris G. U.S. panel says no to prostate screening for healthy men. New York Times. October 6, 2011. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/07/health/07prostate.html

- 24.Rabin RC. Discuss prostate screening with your doctor, experts now say. New York Times. April 11, 2017. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/11/well/live/discuss-prostate-screening-with-your-doctor-experts-now-say.html

- 25.American Urological Association. Our priority: reform the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation process. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://www.auanet.org/advocacy/federal-advocacy/reform-uspstf

- 26.Cooperberg MR. Implications of the new AUA guidelines on prostate cancer detection in the U.S. Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15(7):420. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0420-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prabhu V, Lee T, Loeb S, et al. Twitter response to the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommendations against screening with prostate-specific antigen. BJU Int. 2015;116(1):65-71. doi: 10.1111/bju.12748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preston MA, Batista JL, Wilson KM, et al. Baseline prostate-specific antigen levels in midlife predict lethal prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2705-2711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borghesi M, Ahmed H, Nam R, et al. Complications after systematic, random, and image-guided prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):353-365. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. ; SPCG-4 Investigators . Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):891-899. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70162-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de la Calle CM, Fasulo V, Cowan JE, et al. Clinical utility of 4Kscore, ExosomeDx and magnetic resonance imaging for the early detection of high grade prostate cancer. J Urol. 2021;205(2):452-460. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verbeek JFM, Bangma CH, Kweldam CF, et al. Reducing unnecessary biopsies while detecting clinically significant prostate cancer including cribriform growth with the ERSPC Rotterdam risk calculator and 4Kscore. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(2):138-144. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plym A, Penney KL, Kalia S, et al. Evaluation of a multiethnic polygenic risk score model for prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;djab058. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sathianathen NJ, Kuntz KM, Alarid-Escudero F, et al. Incorporating biomarkers into the primary prostate biopsy setting: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Urol. 2018;200(6):1215-1220. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahdoot M, Wilbur AR, Reese SE, et al. MRI-targeted, systematic, and combined biopsy for prostate cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):917-928. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, et al. ; PRECISION Study Group Collaborators . MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1767-1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, et al. ; PROMIS study group . Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):815-822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stonier T, Simson N, Shah T, et al. The “Is mpMRI Enough” or IMRIE study: a multicentre evaluation of prebiopsy multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging compared with biopsy. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;S2405-4569(20)30271-6. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies C, Castle JT, Stalbow K, Haslam PJ. Prostate mpMRI in the UK: the state of the nation. Clin Radiol. 2019;74(11):894.e11-894.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2019.09.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brizmohun Appayya M, Adshead J, Ahmed HU, et al. National implementation of multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging for prostate cancer detection—recommendations from a UK consensus meeting. BJU Int. 2018;122(1):13-25. doi: 10.1111/bju.14361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh QD. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):458-460. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Results of Sensitivity Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Changes in Rates of PSA Testing Relative to Publication of USPSTF Draft Statement on PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer Among Patients Without Evidence of PSA Testing the Preceding 12-Month Period