Abstract

This cohort study compares current cancer mortality with that in 1971, 50 years after the National Cancer Act designated defeating cancer a national priority and allocated substantial resources to the National Cancer Institute.

The year 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act of 1971, which designated defeating cancer a national priority and allocated substantial resources to the National Cancer Institute, including a budget bypassing congressional approval.1 Subsequently, the National Cancer Institute’s annual budget increased 25-fold, from $227 million in 1971 to $1 billion in 1980 and $6.01 billion in 2019, a total of $137.8 billion. In this cohort study, we compared contemporary cancer mortality with that in 1971.

Methods

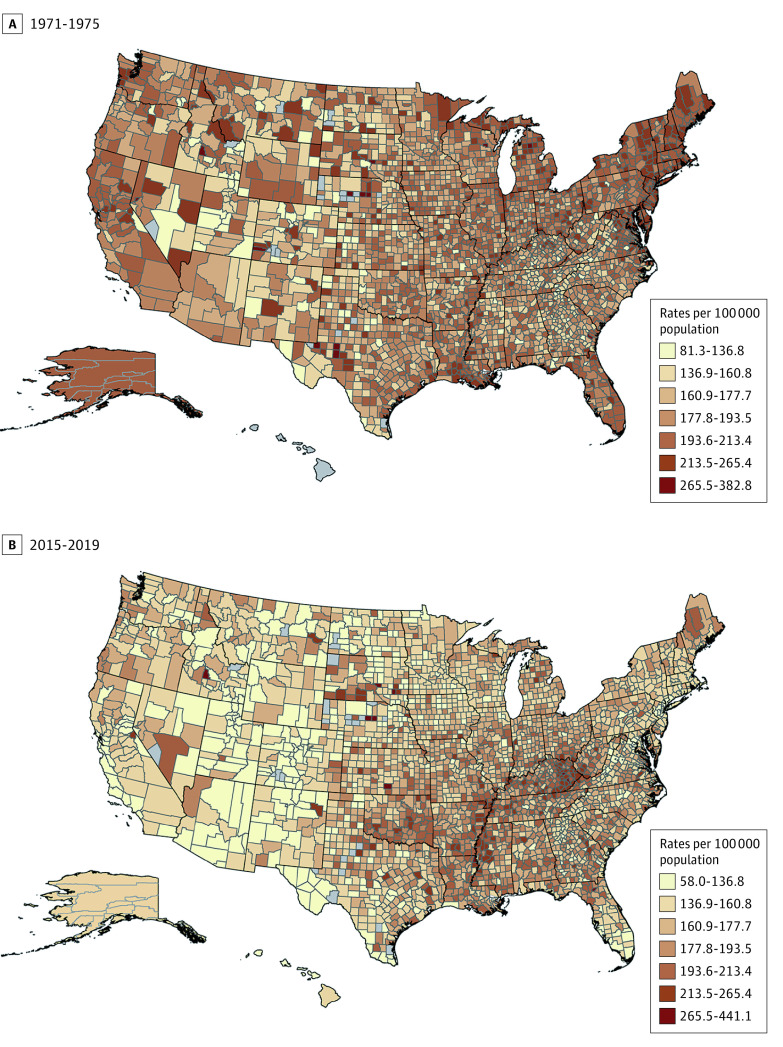

Cancer mortality rates per 100 000 population (age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population) were obtained using SEER*Stat, version 8.3.9, as reported by the National Center for Health Statistics, for all cancers and the top 15 sites in 1971 (81% of cancer deaths) for 1971 through 2019. Rate ratios (RRs) and rate differences were calculated using the standard method to compare mortality in 2019 to 1971 and rate peak years when applicable. ArcMap, version 10.6.1 (Esri), was used to compare county-level rates during 1971 through 1975 vs 2015 through 2019, with natural break categories based on average annual rates during 1971 through 1975. This study was based on deidentified publicly available data and therefore exempt from institutional review board approval.

Results

The Table summarizes cancer mortality in 1971 vs 2019 and peak years when relevant. Rates were statistically significantly lower in 2019 than in 1971 for all cancers combined (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.73-0.74) and for 12 of 15 (80%) sites. During this period, however, rates increased before declining overall and for several cancers, resulting in greater progress from peak years. For example, lung cancer mortality in 2019 was 44% lower than the peak rate in 1993 (RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.56-0.57) vs 13% lower than in 1971 (RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.87-0.88). Conversely, mortality was higher in 2019 than in 1971 for pancreas (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05), esophagus (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.11), and brain (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.10) cancers, despite a considerable decline from the peak rate for the latter 2 cancers. Overall cancer mortality was higher for 845 of 2930 (29%) counties, mostly in the South, although only 41 were statistically significant owing to sparse data (Figure).

Table. Changes in Age-Standardized Mortality Rates for All Cancer and Individual Cancer Sites, 1971-2019.

| Cancer in all sexesa | Rate in 1971 | Rate in peak year (year) | Rate in 2019 | Rate difference from 1971 | Rate difference from peak year | Rate ratio (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019:1971 | 2019:peak year | ||||||

| All sites | 198.9 | 215.1 (1991) | 146.0 | −52.9 | −69.1 | 0.73 (0.73-0.74) | 0.68 (0.68-0.68) |

| Lung and bronchus | 38.2 | 59.1 (1993) | 33.4 | −4.8 | −25.7 | 0.87 (0.87-0.88) | 0.56 (0.56-0.57) |

| Female breast | 31.7 | 33.2 (1989) | 19.4 | −12.3 | −13.8 | 0.61 (0.60-0.62) | 0.58 (0.58-0.59) |

| Prostate | 30.3 | 39.3 (1993) | 18.4 | −11.9 | −20.9 | 0.61 (0.60-0.62) | 0.47 (0.46-0.48) |

| Colon and rectum | 28.8 | NA | 12.8 | −16.0 | NA | 0.44 (0.44-0.45) | NA |

| Pancreas | 10.7 | NA | 11.0 | 0.3 | NA | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | NA |

| Ovary | 10.1 | NA | 6.0 | −4.1 | NA | 0.59 (0.58-0.61) | NA |

| Stomach | 9.7 | NA | 2.8 | −6.9 | NA | 0.28 (0.28-0.29) | NA |

| Leukemia | 8.4 | NA | 5.9 | −2.5 | NA | 0.69 (0.68-0.71) | NA |

| Cervix | 7.1 | NA | 2.2 | −4.9 | NA | 0.31 (0.29-0.32) | NA |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 5.7 | 8.9 (1997) | 5.0 | −0.7 | −3.9 | 0.89 (0.86-0.91) | 0.56 (0.55-0.58) |

| Urinary/bladder | 5.6 | NA | 4.1 | −1.5 | NA | 0.73 (0.71-0.75) | NA |

| Oral cavity and pharynx | 4.4 | NA | 2.5 | −1.9 | NA | 0.57 (0.55-0.58) | NA |

| Brain and other nervous system | 4.0 | 4.9 (1991) | 4.3 | 0.3 | −0.6 | 1.08 (1.05-1.10) | 0.87 (0.85-0.90) |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 3.5 | 4.3 (1991) | 3.4 | −0.1 | −0.9 | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | 0.79 (0.77-0.81) |

| Esophagus | 3.5 | 4.4 (2005) | 3.8 | 0.3 | −0.6 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | 0.86 (0.84-0.88) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Rates for prostate, ovary, and cervix cancers are sex specific.

Rate ratios and 95% CIs are calculated using unrounded rates to 9 decimal places.

Figure. Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates by US County During 1971-1975 and 2015-2019 for All Cancer Sites.

Discussion

The cancer mortality rate has reduced considerably since 1971 overall and for most cancer sites because of improvements in prevention, early detection, and treatment. Specifically, the decline in lung, oral cavity, and bladder cancers largely reflects reduction in smoking because of enhanced public awareness of health consequences, implementation of increased cigarette excise taxes, and comprehensive smoke-free laws.2 Adult smoking prevalence in the US has decreased from 42% in 1965 to 14% in 2018.3

The decline in mortality for female breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancers in part reflects increased detection (and removal) of premalignant lesions and early-stage cancers.3 Screening is estimated to account for 50% of the decline in colorectal cancer mortality between 1975 and 2002.4 Additionally, improvements in surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, precision medicine, and combination therapies over the past 5 decades contribute to mortality reductions for most cancers. One study reported that adjuvant chemotherapy accounted for 63% of the decline in female breast cancer mortality between 2000 and 2012.5 Increased access to care through the Affordable Care Act may also have contributed to more recent declines. Lack of progress in parts of the South largely reflects unequal dissemination of the aforementioned interventions, whereas for pancreatic cancer, the third-leading cause of cancer death, it likely reflects increased prevalence of obesity, as well as lack of major advances in prevention, early detection, and treatment.6

This study is limited by its ecologic nature and inability to establish cause-effect relationships. Nevertheless, these findings demonstrate considerable progress in reducing cancer mortality in the wake of expanded investment following the passage of the National Cancer Act of 1971. Improving equity through investment in the social determinants of health and implementation research is critical to furthering the national cancer-control agenda.

References

- 1.NCI Budget Fact Book archive. National Cancer Institute. Updated January 12, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/budget/fact-book/archive

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: a Report of the Surgeon General. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health, United States, 2019. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/index.htm [PubMed]

- 4.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544-573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plevritis SK, Munoz D, Kurian AW, et al. Association of screening and treatment with breast cancer mortality by molecular subtype in US women, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2018;319(2):154-164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossberg AJ, Chu LC, Deig CR, et al. Multidisciplinary standards of care and recent progress in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(5):375-403. doi: 10.3322/caac.21626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]