Abstract

We present a case of a 51-year-old immunosuppressed man with underlying chronic lymphoproliferative leukaemia (CLL), who presented to us in emergency with breathlessness, hydrophobia, anxiety and restlessness. He had a history of category 3 dog bite 2 months ago and had received a full course of rabies immunoglobulin and antirabies vaccine (ARV) as per the national schedule. As there were frank clinical reports of rabies, the patient was managed according to Milwaukee regimen. The patients died within a week of the appearance of symptoms. The brain autopsy revealed Negri bodies conforming the mortality due to rabies.

Immunosuppressed patients, like our patient who had CLL have low antibody formation after rabies prophylaxis. Antibody titres in immunosuppressed patients need to be measured after the 2–4 weeks of the last injection of ARV to decide whether a booster of ARV needs to be administered or not.

Keywords: public health, emergency medicine

Background

Rabies is a fatal viral disease caused by a rhabdovirus, a negative-stranded RNA virus belonging to genus Lyssavirus of the order Mononegavirales. The virus from the peripheral bite site after entering axon terminals travels in a retrograde direction to effect the Central nervous system.1 The incubation period of rabies ranges from 2 weeks to 6 years and this variability depends on the site of the bite, amount of virus and virus strain. India shares the major burden of global mortality due to rabies. Out of total deaths that happen around the globe annually, 35% of them occurs in India.2 With the global strategic plan of setting the goal of zero human-dog mediated rabies by 2030 the world needs to efficiently prevent and respond through effective use of vaccine medicine and tools, to generate, innovate and measure impact through policies and to sustain commitment and resources to drive progress.3

We report a case of a 51-year-old man who was immunosuppressed, had category 3 dog bite and had received rabies immunoglobulin (RIG) and full course of antirabies vaccine (ARV) but still went on to develop clinical rabies and died within a week of appearance of symptoms.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old man presented to our medical emergency with shortness of breath, irrational fear of water (hydrophobia) and anxiety and restless for 1 day. The shortness of breath was insidious in onset and was not associated with any chest pain, fever, loss of consciousness, frothing, abdominal pain, loose stool or constipation. The patient had a significant past history of long-standing haematological malignancy in form of chronic lymphoproliferative leukaemia (CLL), for which he received six cycles of bendamustine (alkylating chemotherapeutic agent) and rituximab (humanised chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) which he had completed 5 months before the present complaints. There was no underlying history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, etc.

The patient had a history of a dog bite by a street dog over the face and upper trunk 2 months before the current presenting complaints. All the bites were categorised as category 3 bites. The index patient had received a single dose of RIG and full doses of rabies vaccine on day 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28 with rabies the immunoglobulin on day 0.

Investigations

On presentation to our hospital, the patient’s haemoglobin was 137 g/L or 8.5 mmol/L, total leucocyte count was 6200 /mL, platelet counts were 127×109/L. His sodium (141 mmol/L), potassium (3.8 mmol/L), chloride (101 mmol/L), urea (46 mg/dL), creatinine (0.9 mg/dL), bilirubin (0.8 mg/dL) were with in normal limits. MRI of brain was suggestive of focal occipital meningitis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of development of rabies despite receiving complete post exposure prophylaxis in our case could be:

Faulty injection technique

Faulty injection techniques can be one the reasons for inadequate immune response when the route or site of administration of drugs is other than the prescribed.

Inadequate dose of RIG

Inadequate dose of RIG does not trigger the immune response where as if the dose is more than calculated it will suppress the antibody production.

Inappropriate storage

ARV is a heat labile vaccine and generally loose its efficacy when stored at higher temperatures. The vaccine needs to be discarded after 4–6 hours of opening the vial.

Underlying immunosuppressed conditions

Immunosuppressed patients generally does not respond adequately to the intradermal dose of ARV and thus leads to low levels of neutralising antibodies.

Treatment

The patient was managed conservatively (Milwaukee regimen) which included induced coma with deep sedation, ribavirin, interferon gamma.4 The RIG and ARVs were already given to the patient at the time of bite.

Outcome and follow-up

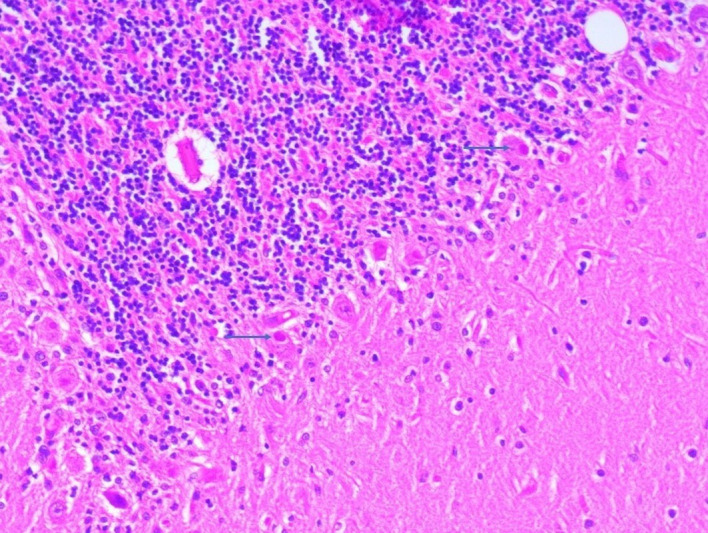

Despite aggressive ventilation/sedation and other supportive measures the patient died within a week of hospitalisation most likely due to respiratory failure with the antecedent cause of rabies encephalitis with the underlying chronic lymphoproliferative disorder. Postmortem autopsy was performed after taking consent from the son of the patient which showed the presence of Negri bodies in the brain tissue (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Presence of multiple Negri bodies (blue arrow) within the Purkinje cells (H&E, ×400) in the patient’s brain tissue.

Discussion

Rabies is caused by bites, licks and scratches on damaged mucosa, by animals (dog (92%), monkey (3.2%) cat (1.85) and fox (0.4%).5 India is a rabies endemic country where there is sustained dog to dog transmission and every animal bite is treated as potentially infectious and should be managed as per the national guidelines for rabies prophylaxis.6 The national guidelines for rabies postexposure prophylaxis recommends infiltration of RIG (human-derived serum 20 IU/kg and equine derived serum 40 IU/kg) and intramuscular antirabies injections (0, 3, 7, 14, 28) and two site intradermal injection of ARV (0, 3, 7, 28) in category 3 bite.6 Routine antirabies antibody level measurement is not recommended in the national guidelines. However, it is advised to measure the protective antibody levels (0.5 IU/mL) in healthcare workers veterinarians and animal handlers and catchers, wild life wardens, etc who are at continuous high risk of exposure to rabid animals.6 7 In above subset of people, the antibody titres are recommended after 6 months of primary vaccination (pre-exposure prophylaxis) and are between 6–12 IU/mL.8

The index patient was immunosuppressed (CLL) and developed rabies encephalitis despite receiving complete standard postexposure prophylaxis regimen as per the national guidelines.6 The probable reason could be failure to achieve adequate rabies antibody titres after vaccination which were not measured in our patient. Another reason for the low level of antibody formation may be linked to the dose of the RIG administered as higher dose can suppress antibody production leading to low levels of Antirabies antibodies.9 A study by Kopel et al found undetectable levels of neutralising antibodies in response to rabies vaccination in an immunosuppressed individual who died before receiving the fifth dose of ARV.10 Further the same study found that 7 out of 15 immunocompromised patients did not exhibit the minimum acceptable level of antibodies after a complete post exposure prophylaxis regimen as in the Index case. Similarly, Pancharoen et al demonstrated failure to develop neutralising antibodies in a 6-year-old PHLIV child who had received both intramuscular pre exposure and intradermal postexposure rabies vaccination.11 A study by Jaijaroensup et al also observed inadequate neutralising antibody titres among nine HIV-infected patients who had proven rabies infection despite the complete post exposure prophylaxis.12

In immunosuppressed patients, antirabies antibodies estimation should preferably be done 14 days after the completion of the course of vaccination to assess the need for the additional booster doses of vaccine as per the national guidelines for rabies prophylaxis.6 However, Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends antirabies antibody titres between 2 and 4 weeks of competition of pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis in conditions such as immunosuppressed persons, significant deviation in prophylaxis schedule, the patient initiated vaccination internationally with a products of questionable quality or persons antibody status is being monitored routinely due to occupational exposure to rabies virus.13

Thus, the authors also propose measuring antirabies antibodies titres after 14 days of competition of postexposure prophylaxis for rabies in immunosuppressed patients and if antirabies antibodies titres levels are less than 0.5 IU/mL, a booster dose of the ARV of the same batch number and route of administration as earlier is recommended.

Learning points.

In immunosuppressed patients sustaining a mammalian bite, the neutralising antibody levels done at 2 weeks of completion of postexposure prophylaxis are important in identifying the need for booster dose of antirabies vaccine (ARV).

The monthly reporting format should have a mandatory column for the immunosuppressed patients having dog/animal bite with recording of rabies immunoglobulin and ARV and whether the antibody titres are done after 2-week interval for these patients or not and citing reasons if not done.

Sensitisation of healthcare workers at antirabies centre and awareness of patients and the general population regarding taking a sample of the immunosuppressed patient for antibody titres should be done timely through continuous medical education and specific information education and communication materials.

Footnotes

Contributors: RM managed the patient during his admission. VS critically reviewed the manuscript. DC did the histopathology of the specimen. KR wrote the manuscript and finalised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from next of kin.

References

- 1.Dietzschold B, Li J, Faber M, et al. Concepts in the pathogenesis of rabies. Future Virol 2008;3:481–90. 10.2217/17460794.3.5.481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Epidemiology and burden of disease. WHO, 2018|. Available: http://www.who.int/rabies/epidemiology/en/ [Accessed 15 Dec 2020].

- 3.New global strategic plan to eliminate dog-mediated rabies by 2030. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/new-global-strategic-plan-to-eliminate-dog-mediated-rabies-by-2030 [Accessed 15 Jun 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.World Health Organization . WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report - World Health Organization, 2018. Available: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=-nKyDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&ots=UqfHkpWEmG&sig=7HuCXRAjTf9FeD5DxCatvXn87oA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false [Accessed 15 Jun 2021].

- 5.Ichhpujani RL, Mala C, Veena M. Epidemiology of animal bites and rabies cases in India. A multicentric study. J Commun Dis 2008;40:27–36 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19127666/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Centre for Disease Control . National Rabies Control Programme - National Guidelines on Rabies Prophylaxis, 2015. Available: http://pbhealth.gov.in/guidelineforrabiesprophylasix.pdf

- 7.WHO . Symptoms & pre-exposure immunization. WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC - Doctors: Rabies Serology - Rabies. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/specific_groups/doctors/serology.html [Accessed 14 Dec 2020].

- 9.Precautions or contraindications for rabies vaccination | specific groups | CDC. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/specific_groups/hcp/vaccination_precautions.html [Accessed 27 Sep 2021].

- 10.Kopel E, Oren G, Sidi Y, et al. Inadequate antibody response to rabies vaccine in immunocompromised patient. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:1493–5. 10.3201/eid1809.111833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pancharoen C, Thisyakorn U, Tantawichien T, et al. Failure of pre- and postexposure rabies vaccinations in a child infected with HIV. Scand J Infect Dis 2001;33:390–1. 10.1080/003655401750174183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaijaroensup W, Tantawichien T, Khawplod P, et al. Postexposure rabies vaccination in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:913–4. 10.1086/517241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabies serology | specific groups | CDC. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/specific_groups/hcp/serology.html [Accessed 16 Oct 2021].