Abstract

Background and Objectives

Adapted ketogenic diet (AKD) and caloric restriction (CR) have been suggested as alternative therapeutic strategies for multiple sclerosis (MS), but information on their impact on neuroaxonal damage is lacking. Thus, we explored the impact of diets on serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) levels in patients with relapsing-remitting MS.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated a prospective randomized controlled trial of 60 patients with MS who were on a common diet or ketogenic diet or fasting. We examined sNfL levels of 40 participants at baseline and at the end of the study after 6 months using single molecule array assay.

Results

sNfL levels were investigated in 9 controls, 14 participants on CR, and 17 participants on AKD. Correlation analysis showed an association of sNfL with age and disease duration; an association was also found between sNfL and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite. AKD significantly reduced sNfL levels at 6 months compared with the common diet group (p = 0.001).

Discussion

For clinical or study use, consider that AKD may incline sNfL levels independent of relapse activity up to 3 months after initiation. At 6 months, AKD, which complements current therapies, reduced sNfL levels, therefore suggesting potential neuroprotective effects in MS. A single cycle of seven-day fasting did not affect sNfL. AKD may be an addition to the armamentarium to help clinicians support patients with MS in a personalized manner with tailored diet strategies.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), effective therapeutic strategies and sensitive biomarkers to evaluate drug efficacy and disease course are urgently needed. Serum neurofilament light chain protein (sNfL) has recently been suggested as a promising candidate for a reliable, easy-to-use biomarker of neuroaxonal damage that accurately detects changes over both long and short time intervals in MS.1,2 After axonal injury, NfL is elevated in both the CSF and in the peripheral blood, where it can be measured by highly sensitive single molecule assays (SiMoA).3,4 Studies have suggested a possible role of caloric restriction (CR) and adapted ketogenic diet (AKD) on neuroinflammation in MS and other neurologic disorders.5-7 The observed diet-induced improvement of neuronal resistance and axonal survival are clearly neuroprotective, but the underlying mechanisms remain elusive.5,8 In the present study, we investigated whether AKD and CR in comparison to common diet (CD) may affect neurodegeneration as measured by sNfL levels in MS.

Methods

Clinical Trial Design, Patients, Study Setting, Interventions, and Primary Outcome

All study details were described previously6,7,9 and are presented in Supplemental Methods. This study was a three-armed parallel group, single-centered, controlled and randomized clinical trial. This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01538355.

Outcome Measure

The sNfL concentration of 40 patients was quantified in 2020/2021.

sNfL Measurements

We applied the same method as described recently3 and presented in Supplemental Methods, links.lww.com/NXI/A653. In brief, sNfL was measured in several rounds by SiMoA HD-1 (Quanterix) using the NF-Light Advantage Kit (Quanterix) from the same batch according to the manufacturer's instructions. sNfL analysis was performed in a blinded fashion without clinical information about patients.

Control Diet

Patients on CD met the criteria of a common diet in the German population as described in the National Nutrition Survey II (mri.bund.de/de/institute/ernaehrungsverhalten/publikationen/forschungsprojekte/nvsii/).

Caloric Restriction

As previously described, a single cycle of 7-day CR (200–350 kcal/d) was performed at study outset; a 3-day stepwise reintroduction to an isocaloric common diet was performed starting on day 8.6

Adapted Ketogenic Diet

Patients followed an AKD for 6 months from study outset. We recommended an average daily intake of <50 g carbohydrates, > 160 g fat (omega 6 vs omega 3 ratio 2:1), and average protein intake ≤100 g per day. Compliance during CR and AKD was monitored via ketosis self-measured in blood and urine.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the local ethics committee in the frame of the IGEL study (ethics no. EA1/105/11). All patients included in this study signed specific informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

We used analyses of covariance to test for group differences using sNfL baseline data, number of clinical relapses over the course of the study, and body mass index (BMI) as covariates. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test analysis was used for intragroup statistics.

Data Availability

Anonymized data will be made available on request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Situation Before Dietary Intervention

Baseline Intergroup Comparison: No Differences in Outcome

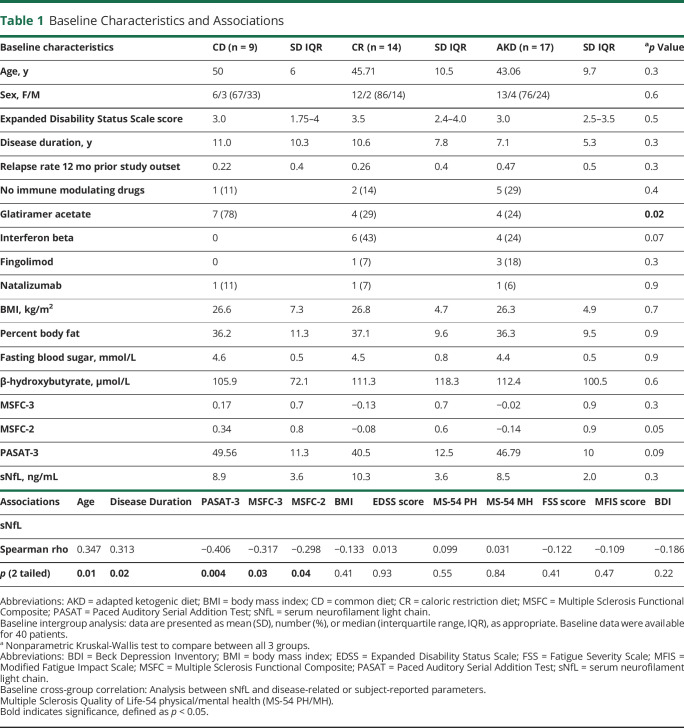

Patient demographics did not differ significantly when the different intervention groups were compared (Table 1). The use of the disease-modifying therapy (DMT) glatiramer acetate was significantly different between the groups, but this is clinically not relevant. sNfL levels did not differ significantly between the 3 groups before dietary interventions. These data indicate that the dietary habits of the patients involved in the study did not influence the sNfL concentration at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Associations

Next, we correlated disease-related and participant-reported parameters across all groups involving all individuals of all experimental groups. We found a significant association between sNfL and age (r = 0.347, p < 0.05) and disease duration (r = 0.313, p < 0.05) confirming observations of other groups. Moreover, we observed a significant inverse correlation between sNfL and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite 2 and 3 (MSFC 2 + 3) (r = -0.298, p < 0.05; r = -0.317, p < 0.05) and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test 3 (r = −0.298, p < 0.005) (Table 1; eFigure 1–eFigure 5, links.lww.com/NXI/A653). Of interest, sNfL levels did not significantly correlate with BMI or with the clinically meaningful neurologic measure Expanded Disability Status Scale. There was also no correlation with the self-report questionnaires Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MS-54), Fatigue Severity Scale, Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, and Beck Depression Inventory.

NfL Alterations as Consequence of Dietary Intervention

Intragroup Comparison: AKD Induced Significant Reductions in sNfL Within 6 months

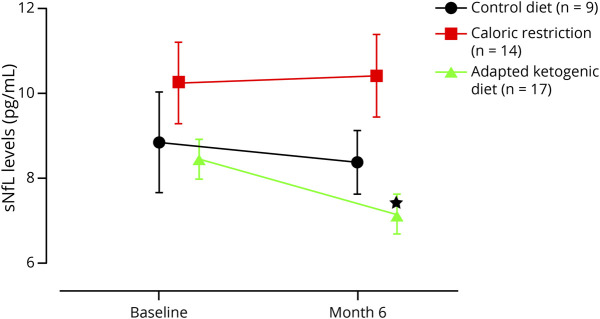

In the AKD group (n = 17), we found a significant decrease in the sNfL level from 8.5 at baseline (no dietary intervention) to 7.1 pg/mL (mean difference -1.307; 95% CI -2.256 to -0.357; p < 0.05) at the end of the study after 6 months. The analysis of the CR group (n = 14) and CD group (n = 9) showed similar sNfL levels at baseline and at the final visit (Figure 1 and eTable 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A653).

Figure 1. Intra-Group Comparison – Adapted Ketogenic Diet Lowers the Serum Concentration of Neurofilament Light Chain II.

Alterations of serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) levels induced by caloric restriction and adapted ketogenic diet. Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean and were measured at baseline and retested at 6 months for all groups. p values indicate Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test analysis, *p < 0.05.

Intergroup Comparison: AKD Lowers sNfL Levels in Comparison to Common Diet

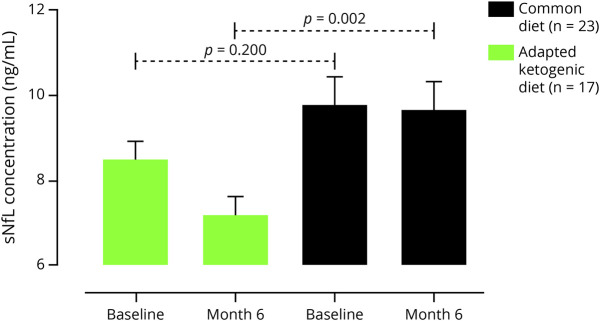

We used baseline sNfL concentrations, relapse rate, and Δ-BMI as covariates for between-group evaluation. At the end of the study, we observed a significant decline in sNfL levels (Figure 2 and eTable 2, links.lww.com/NXI/A653) when we compared AKD with CD (adjusted difference -2.145 ± 0.615; 95% CI -3.393 to -0.897; p = 0.001) after 6 months. We did not find a difference in sNfL levels between CR and CD groups at month 3 (adjusted difference 1.24 ± 1.71; 95% CI -2.236 to 4.716; p = 0.682).

Figure 2. Comparison of sNfL Levels in Patients With MS on Adapted Ketogenic Diet With Common Diet.

After 6 months of adapted ketogenic diet, the serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) concentration declined significantly compared to the common diet group. Data were measured at baseline and retested at 6 months. Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean. **p < 0.01, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for relapse rate, BMI and baseline dependencies.

Relapse Rate and sNfL Over the Course of the Study

Twelve months prior study outset, the relapse rate did not differ significantly between the groups (Table 1). In the course of the study, 3 relapses in the CD group, 2 relapses in the CR group, and 1 relapse in the AKD group were reported. When analyzing sNfL levels at month 3, we detected a significant increase over all groups (eFigure 6 and eTable 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A653). After excluding samples from patients with relapse activity, the sNfL levels of the AKD group remained elevated (eFigure 7, links.lww.com/NXI/A653).

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial we investigated the impact of intermittent fasting/CR and AKD on sNfL levels in patients with MS. In the examined groups, sNfL levels were comparable with previous studies using the same methodology supporting the reliability of our results and of the applied assay analysis method.3 However, earlier studies have described higher sNfL levels due to various internal protocols, as recently discussed.10

This setting not only allowed assessment of the relative effects of AKD treatment vs common diet and 7-day fasting in a parallel randomized design but also provided the opportunity to study the relation of sNfL as a specific marker of neuroaxonal damage with other anthropometric, clinical, and patient-reported measures of disease activity and severity obtained under good clinical practice conditions.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in this analysis do not suggest any relevant selection bias. sNfL concentrations in patients were similar over all groups at baseline. sNfL levels at baseline were correlated with functional markers of disease activity (e.g., PASAT and MSFC) confirming recent reports.3 Although diet as an environmental factor has been acknowledged in MS, its precise role in the pathogenesis of MS is still far from clear. Moreover, dietary interventions are rapidly gaining popularity within the MS community, but little is known about their safety. AKD and CR have been suggested to induce autophagy and to improve gut microbiota, redox status, and regulatory T cells in a variety of diseases.5,7,9,11,12

It has previously been shown that NfL levels, as a neuroaxonal integrity parameter and marker of treatment response, decrease after initiation of DMTs3 In line with this, our results indicate that AKD may influence sNfL levels in patients with MS. More studies are necessary to evaluate the longitudinal impact of repeated fasting cycles on sNfL levels in MS.

Our analysis reflects a significant relationship between AKD and declining sNfL levels at 6 months. This suggests that AKD may benefit the course of disease in MS. However, more comprehensive studies with an expanded time span are needed to examine whether effects could relate to the diet itself rather than its impact on MS. The limitations of our study include its short observation time of 6 months, MRI was not performed and a limited power, due to a relatively small number of participants (n = 40 analyzed patients). It should also be noted that the extent of variation indicating a clinically meaningful change in longitudinal sNfL measurements has not yet been defined. However, we also found increased sNfL levels in the AKD group, independent of relapse activity at month 3. Our observation could be due to autophagy of which AKD and CR are strong inductors.11,12 Of interest, it was reported that autophagy promotes intracellular degradation of cytoskeleton but also seems to be essential for the survival of neuronal cells.13 However, it is likely that release of degradation products would increase sNfL levels extracellularly (and thus in serum) at least in the short term—thus our results would be consistent with the latter results of different groups.

AKD needs more time than CR to activate homeostatic processes, e.g., autophagy, due to the process of keto-adaptation and slower/lower ketone body excess. This may explain why we did not detect an increase in sNfL in the CR group at month 3.

Overall, our study suggests that an AKD offers an avenue to impact sNfL levels, which seems to be a promising biomarker in neuroinflammatory diseases, supporting the use of dietary interventions as a treatment tool for MS. These findings are of urgent medical interest because such dietetic strategies exhibit few unwanted side effects.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (SFB CRC-TR-128 to FZ and SB; CRC-1080 to FZ; SFB 1292 to FZ; and the Myelin Projekt e.V.; Familie Ernst Wendt Stiftung Köln; and Dr. Schär AG which were not involved in any decision-making processes relating to the study or its participants. The authors thank Dr. Cheryl Ernest for proofreading and editing the manuscript.

Glossary

- AKD

adapted ketogenic diet

- BMI

body mass index

- CD

common diet

- CR

caloric restriction

- DMT

disease-modifying therapy

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- MSFC

Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite

- PASAT

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test

- SiMoA

single molecule assay

- sNfL

serum neurofilament light chain

Appendix. Authors

Contributor Information

Falk Steffen, Email: f.steffen@uni-mainz.de.

Frauke Zipp, Email: zipp@uni-mainz.de.

Stefan Bittner, Email: bittner@uni-mainz.de.

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

M. Bock, F. Steffen, S, Bittner, and F. Zipp report no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Uphaus T, Bittner S, Gröschel S, et al. NfL (neurofilament light chain) levels as a predictive marker for long-term outcome after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(11):3077-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pape K, Steffen F, Zipp F, Bittner S. Supplementary medication in multiple sclerosis: real-world experience and potential interference with neurofilament light chain measurement. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6(3):2055217320936318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittner S, Steffen F, Uphaus T, et al. Clinical implications of serum neurofilament in newly diagnosed MS patients: a longitudinal multicentre cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2020;56:102807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siller N, Kuhle J, Muthuraman M, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a biomarker of acute and chronic neuronal damage in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25(5):678-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DY, Hao J, Liu R, Turner G, Shi FD, Rho JM. Inflammation-mediated memory dysfunction and effects of a ketogenic diet in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bock M, Karber M, Kuhn H. Ketogenic diets attenuate cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase gene expression in multiple sclerosis. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:293-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi IY, Piccio L, Childress P, et al. A diet mimicking fasting promotes regeneration and reduces autoimmunity and multiple sclerosis symptoms. Cell Rep. 2016;15(10):2136-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ni FF, Li CR, Liao JX, et al. The effects of ketogenic diet on the Th17/Treg cells imbalance in patients with intractable childhood epilepsy. Seizure. 2016;38:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swidsinski A, Dörffel Y, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Reduced mass and diversity of the colonic microbiome in patients with multiple sclerosis and their improvement with ketogenic diet. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barro C, Chitnis T, Weiner HL. Blood neurofilament light: a critical review of its application to neurologic disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(12):2508-2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang BH, Hou Q, Lu YQ, et al. Ketogenic diet attenuates neuronal injury via autophagy and mitochondrial pathways in pentylenetetrazol-kindled seizures. Brain Res. 2018;1678:106-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alirezaei M, Kemball CC, Flynn CT, Wood MR, Whitton JL, Kiosses WB. Short-term fasting induces profound neuronal autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6(6):702-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen JX, Sun YJ, Wang P, et al. Induction of autophagy by TOCP in differentiated human neuroblastoma cells lead to degradation of cytoskeletal components and inhibition of neurite outgrowth. Toxicology. 2013;310:92-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be made available on request from any qualified investigator.