Abstract

A multilaboratory study was undertaken to determine the accuracy of the current National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) oxacillin breakpoints for broth microdilution and disk diffusion testing of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) by using a PCR assay for mecA as the reference method. Fifty well-characterized strains of CoNS were tested for oxacillin susceptibility by the NCCLS broth microdilution and disk diffusion procedures in 11 laboratories. In addition, organisms were inoculated onto a pair of commercially prepared oxacillin agar screen plates containing 6 μg of oxacillin per ml and 4% NaCl. The results of this study and of several other published reports suggest that, in order to reliably detect the presence of resistance mediated by mecA, the oxacillin MIC breakpoint for defining resistance in CoNS should be lowered from ≥4 to ≥0.5 μg/ml and the breakpoint for susceptibility should be lowered from ≤2 to ≤0.25 μg/ml. In addition, a single disk diffusion breakpoint of ≤17 mm for resistance and ≥18 mm for susceptibility is suggested. Due to the poor sensitivity of the oxacillin agar screen plate for predicting resistance in this study, this test can no longer be recommended for use with CoNS. The proposed interpretive criteria for testing CoNS have been adopted by the NCCLS.

The coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) comprise a group of species frequently associated with both community-acquired and nosocomial bloodstream infections, particularly in patients with indwelling catheters or other medical devices (2, 9, 15, 22). Isolates from a variety of CoNS species, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, S. haemolyticus, S. saprophyticus, S. simulans, and S. warneri have been reported to harbor the mecA determinant, which encodes a modified penicillin binding protein (PBP2a) and is responsible for resistance to the penicillinase-resistant penicillins, such as dicloxacillin, methicillin, nafcillin, and oxacillin (6, 12, 18, 20). The presence of the mecA gene in a staphylococcal isolate is considered synonymous with oxacillin resistance (1, 4, 17, 19). Thus, genetic assays for mecA have often been used as the reference method for evaluating new methods of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for staphylococci (1, 3, 6, 10, 16, 23).

Many investigators have reported discrepancies between the results of mecA genetic assays and MIC tests for oxacillin resistance when the results of MIC testing were interpreted by using the current National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) breakpoints of ≤2 μg/ml for susceptibility and ≥4 μg/ml for resistance (3, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 17, 21). There are also conflicting data regarding the accuracy of the oxacillin agar screen test, in which an agar plate containing 6 μg of oxacillin per ml and 4% NaCl is inoculated with a heavy suspension of the staphylococcal test organism, compared to the results of a PCR assay for mecA (3, 8, 17, 23). More recently, the accuracy of the oxacillin disk diffusion test also has come into question (3, 6, 9, 23). However, none of the studies cited above were conducted in multiple laboratories, although strains from many institutions and geographic locations were sampled.

To determine the accuracy of the oxacillin broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and agar screen tests, we tested 50 well-characterized CoNS strains in 11 laboratories and compared those results to the results of a PCR assay for mecA performed in 3 laboratories. The goal of this study was to either validate the existing NCCLS breakpoints or modify the breakpoints to make them conform to the results of genotypic (mecA) testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and study format.

Fifty strains of CoNS were selected from the strain collections at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the University of California at San Francisco, and the University of Iowa College of Medicine. Isolates were frozen and distributed to 10 laboratories with previous experience in performing broth microdilution MIC and disk diffusion testing. The laboratories were Dade MicroScan, West Sacramento, Calif.; Duke University, Durham, N.C.; The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Md.; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Ill.; Ohio State University, Columbus; Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.; University of California at San Francisco; University of Iowa, Iowa City; University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; and Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo. Testing was also performed at the Nosocomial Pathogens Laboratory Branch at CDC. All materials for the study were supplied to the laboratories except for the Mueller-Hinton agar plates for disk diffusion testing, which were purchased locally. All laboratories performed broth microdilution (14), disk diffusion (13), and the oxacillin agar screening test (13), using the methods described by NCCLS, on the same 50 test strains. Previous test results from an additional 200 isolates of CoNS from CDC (see below) were reanalyzed by using the new MIC and disk diffusion breakpoints.

Organisms tested.

Most of the CoNS strains chosen for this study had previously demonstrated oxacillin MICs ranging from 0.25 to 4 μg/ml. The organisms were identified by standard biochemical methods (7). The distribution of species is as follows (with the total number of strains/number of mecA positive strains, given in parentheses after each species name): S. epidermidis (27/18), S. hominis (8/5), S. warneri (6/1), S. haemolyticus (3/3), S. lugdunensis (2/0), S. saprophyticus (2/1), S. capitis (1/0), and S. simulans (1/1). S. aureus ATCC 29213, ATCC 25923, and ATCC 43300 were included for quality control (13, 14). Each strain was subcultured to ensure purity and was frozen for distribution to the participating laboratories. Identification to species level and the presence or absence of mecA were verified or determined prior to shipment. The additional 200 isolates of CoNS included 141 isolates chosen from the CDC strain collection (total number/number mecA positive), i.e., S. epidermidis (48/43), S. haemolyticus (27/23), S. hominis (13/8), S. lugdunensis (9/0), S. simulans (8/4), S. saprophyticus (7/1), S. warneri (5/2), S. intermedius (5/1), S. cohnii (4/0), S. xylosus (3/0), S. hyicus (2/0), S. auricularis (2/0), S. capitis (1/0), S. saccharolyticus (1/0), and Staphylococcus species (5/1), and 59 fresh clinical isolates of CoNS from five laboratories around the United States, i.e., S. epidermidis (47/35), S. hominis (8/6), S. capitis (2/0), S. warneri (1/0), and S. auricularis (1/0). All 200 of these were tested previously at CDC with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) by the NCCLS method.

Inoculum preparation.

Inoculum for all tests was prepared from a blood agar plate that had been streaked with a single colony from an initial subculture plate and incubated for 18 to 24 h. The test inoculum was prepared by removing growth from the blood agar plate, inoculating it directly into Mueller-Hinton broth, and adjusting the inoculum to equal a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (14). The final inoculum for the broth microdilution tests was determined from both MIC plates for each organism by each laboratory by removing 20 μl from a growth control well, diluting it in 10 ml of saline just after inoculation, and, after mixing well, spreading 100 μl onto each of two blood agar plates.

Broth microdilution tests.

Panels were prepared by two laboratories, CDC and Dade MicroScan, by following NCCLS reference procedures (13, 14). The panels contained oxacillin (range, 0.015 to 32 μg/ml), vancomycin (0.06 to 64 μg/ml), penicillin (0.12 to 128 μg/ml), and erythromycin (0.03 to 32 μg/ml). Vancomycin was obtained from Lilly Research Laboratories (Indianapolis, Ind.); penicillin, erythromycin, and oxacillin were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). (Data for drugs other than oxacillin are not reported here.) The panels were made using two different lots of CAMHB, i.e., a common lot of CAMHB (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) used by both laboratories and one unique lot (from Acumedia, Westlake, Ohio, for CDC and from Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems [BDMS], Cockeysville, Md., for MicroScan; the latter was specifically prepared for MicroScan panels). The CAMHB for oxacillin testing was supplemented with 2% NaCl. Inoculation was performed and final inoculum counts were determined on all MIC plates as described above. Panels were incubated at 35°C and read at 24 h to determine the oxacillin MICs. The significance of differences between the results of the MIC tests determined with the different lots of media was determined by the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Disk diffusion tests.

Each laboratory performed disk diffusion tests using locally obtained Mueller-Hinton agar. Seven laboratories used commercially prepared BDMS Mueller-Hinton agar, three laboratories used commercially prepared Remel (Lenexa, Kans.) Mueller-Hinton agar, and one laboratory prepared its plates in-house using BDMS agar. No common lot of medium was included. Oxacillin disks (1 μg; BDMS) were supplied to each laboratory for the study. Oxacillin zone diameters were measured after 24 h of incubation in ambient air at 35°C.

Oxacillin agar screen test.

The oxacillin agar screen test was performed with agar plates from two commercial sources, Remel and BDMS. The plates were inoculated in two ways with a cotton swab dipped into the 0.5 McFarland suspension: (i) by leaving the swab wet, and (ii) after expressing the fluid, as would be done for disk diffusion testing. For both methods, the plates were inoculated by making a spot about the diameter of a dime (∼15 mm) onto a quadrant of the plate. The plates were incubated in ambient air at 35°C and read at 24 and 48 h. Growth of >1 colony was interpreted as positive.

PCR for mecA.

The PCR assays for mecA were performed at CDC as described by Murakami et al. (12). The assays were also performed at the University of Iowa College of Medicine and Massachusetts General Hospital by using in-house protocols.

RESULTS

Inoculum determinations.

Each laboratory determined the inoculum density of each study organism by sampling one well of each MIC plate. The results from each laboratory for each species were averaged, and the mean results are shown in Table 1. Most of the viable organism counts (observed range, 3 × 104 to 1.2 × 106 CFU/ml) were below the recommended density of 5 × 105 CFU/ml (ideal range, 3 × 105 to 7 × 105 CFU/ml). Only the S. lugdunensis isolates produced average CFU counts near the midpoint of the ideal range on both MIC panels.

TABLE 1.

Inoculum counts performed on a single well of a broth microdilution plate

| Species (no. of strains) | Mean (105) CFU/ml (range)a on a:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| CDC plate | MicroScan plate | |

| S. epidermidis (27) | 1.78 (1.1–3.5) | 1.63 (0.6–3.6) |

| S. hominis (8) | 0.89 (0.3–2.1) | 0.92 (0.3–2.6) |

| S. warneri (6) | 1.60 (0.6–2.6) | 1.53 (0.6–3.6) |

| S. haemolyticus (3) | 1.34 (0.6–2.2) | 1.17 (0.2–2.7) |

| S. lugdunensis (2) | 4.43b (0.9–10.6) | 4.14b (0.9–12.1) |

| S. saprophyticus (2) | 2.57 (0.8–4.1) | 2.31 (0.7–5.1) |

| S. capitis (1) | 2.92 (0.98–5.4) | 2.58 (0.7–4.8) |

| S. simulans (1) | 2.02 (0.5–3.5) | 1.66 (0.2–3.2) |

The means represent the average counts from both MIC plates for each organism for each species counted in each laboratory. Each range consists of the mean from the laboratory with the lowest average counts per species and the mean from the laboratory with the highest average counts per species.

Counts within allowable range for final inoculum in MIC plates.

The effect of the medium on MIC results.

The concentrations of oxacillin required to inhibit the growth of the 50 study isolates of CoNS were determined in 11 laboratories using two different MIC panels. Each reference MIC panel (one prepared at CDC and the other prepared at MicroScan) contained a common lot of medium (Difco) and a unique lot (Acumedia or BDMS). The oxacillin MIC results for the mecA-negative S. epidermidis isolates were highly comparable regardless of the source of medium used, with ≥99% of values within ±1 log2 dilution (Table 2). However, significant variations in MICs were noted when the results generated with the common lot of Difco broth prepared by CDC were compared to those generated with the Difco broth prepared by MicroScan for mecA-negative organisms other than S. epidermidis and for all mecA-positive organisms. Similar differences were noted when the MIC results with the CDC Difco broth were compared to the results with the CDC Acumedia broth, and when the results with the MicroScan Difco broth were compared to the results with the MicroScan BDMS broth (Table 2). When the MIC results for all organisms were pooled, the Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated that the MIC results generated with the MicroScan Difco broth were significantly lower than the results with the CDC Difco broth (P < 0.0001). Similarly, the MicroScan BDMS results were significantly lower than the MicroScan Difco results (P < 0.03). The overall results obtained with the CDC Difco broth and the CDC Acumedia broth were not significantly different (P = 0.25). All of the quality control results for oxacillin testing of S. aureus ATCC 29213 by all 11 laboratories were within the published control ranges on each day of testing.

TABLE 2.

Effect of medium source on oxacillin MICs expressed as dilution difference of MICs

| Organism group and media | No. of results with a dilution difference of:

|

% of results within a dilution difference of ±1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥−3 | −2 | −1a | 0 | +1b | +2 | ≥+3 | ||

| mecA negative | ||||||||

| S. epidermidis | ||||||||

| CDC Difco vs. MicroScan Difco | 5 | 76 | 16 | 100 | ||||

| CDC Difco vs. CDC Acumedia | 13 | 77 | 9 | 1 | 99.0 | |||

| MicroScan Difco vs. MicroScan BDMS | 1 | 37 | 58 | 2 | 99.0 | |||

| Other species | ||||||||

| CDC Difco vs. MicroScan Difco | 8 | 32 | 71 | 18 | 93.8 | |||

| CDC Difco vs. CDC Acumedia | 19 | 38 | 54 | 6 | 83.8 | |||

| MicroScan Difco vs. MicroScan BDMS | 8 | 44 | 77 | 1 | 93.8 | |||

| mecA positive | ||||||||

| S. epidermidis | ||||||||

| CDC Difco vs. MicroScan Difco | 29 | 50 | 77 | 29 | 5 | 1 | 58.1 | |

| CDC Difco vs. CDC Acumedia | 1 | 7 | 18 | 45 | 54 | 46 | 11 | 64.3 |

| MicroScan Difco vs. MicroScan BDMS | 2 | 3 | 12 | 45 | 91 | 33 | 11 | 75.1 |

| Other species | ||||||||

| CDC Difco vs. MicroScan Difco | 2 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 15 | 2 | 76.5 | |

| CDC Difco vs. CDC Acumedia | 26 | 12 | 9 | 22 | 6 | 49.3 | ||

| MicroScan Difco vs. MicroScan BDMS | 1 | 6 | 21 | 39 | 12 | 3 | 87.8 | |

The second parameter in the comparison is lower.

The second parameter in the comparison is higher.

New MIC breakpoints.

After examining the interpretive errors for each potential set of breakpoints (Table 3), we selected the values of ≤0.25 μg/ml for susceptibility and ≥0.5 μg/ml for resistance, since they showed the lowest numbers of category errors with these data sets and with other data sets reported in the literature. The percent correct values observed for each broth medium by using the current and proposed oxacillin MIC breakpoints are shown in Table 4. For mecA-positive strains, any MIC result that was not ≥0.5 μg/ml (proposed breakpoint) or ≥4.0 μg/ml (current breakpoint) was considered an error. Conversely, for mecA-negative strains, any oxacillin MIC result of ≤0.25 μg/ml (proposed breakpoint) or ≤2.0 μg/ml (current breakpoint) was considered an error. The oxacillin MICs of a large percentage of the mecA-positive strains were below the current NCCLS resistance breakpoint of ≥4.0 μg/ml with all four media (Table 4). However, very few errors were obtained with mecA-negative strains by using the current breakpoints.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of results with different reference plates and medium manufacturers by mecA and oxacillin MIC breakpoint

| Plate/medium | No. (%) of results with the indicated MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

mecA-positive strains (n = 318)

|

mecA-negative strains (n = 230)

|

|||||||

| ≥4 | ≥2 | ≥1 | ≥0.5 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.25 | |

| CDC/Difco | 182 (57) | 260 (82) | 290 (91) | 298 (94) | 224a (99) | 211 (93) | 195 (86) | 166a (73) |

| MicroScan/Difco | 82 (26) | 145 (46) | 255 (80) | 299 (94) | 230 (100) | 218 (95) | 197 (86) | 171 (74) |

| CDC/Acumedia | 198 (62) | 240 (76) | 257 (81) | 267 (84) | 222b (98) | 216 (96) | 202 (89) | 175b (77) |

| MicroScan/BDMS | 143 (45) | 209 (66) | 272 (86) | 297 (93) | 230 (100) | 227 (99) | 211 (92) | 186 (81) |

n = 227. Differences were due to growth failures in some MIC plates.

n = 226. Differences were due to growth failures in some MIC plates.

TABLE 4.

Correlation of mecA PCR test results with MIC category results for current and proposed oxacillin breakpoints

| Organism group (no. of tests) | % Correct values with the indicated medium by MIC breakpointa

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed (≤0.25 = S; ≥0.5 = R)

|

Current (≤2.0 = S; ≥4.0 = R)

|

|||||||

| CDC Difco | MScan Difco | CDC Acumedia | MScan BDMS | CDC Difco | MScan Difco | CDC Acumedia | MScan BDMS | |

| mecA positive | ||||||||

| S. epidermidis (198) | 95.5 | 96.0 | 94.4 | 93.4 | 52.5 | 8.1 | 72.3 | 40.9 |

| Other species (120) | 90.8 | 90.8 | 66.7 | 93.3 | 65.0 | 55.0 | 40.8 | 51.7 |

| All strains | 93.7 | 94.0 | 84.0 | 93.4 | 57.2 | 25.8 | 62.3 | 45.0 |

| mecA negative | ||||||||

| S. epidermidis (99) | 100 (97)b | 100 (98) | 99.0 (97) | 100 (99) | 100 (97) | 100 (98) | 100 (97) | 100 (99) |

| Other species (132) | 52.7 (129) | 55.0 (131) | 60.9 (126) | 66.4 (131) | 97.7 (129) | 100 (131) | 96.9 (126) | 100 (131) |

| All strains | 73.1 | 74.3 | 77.4 | 80.9 | 98.7 | 100 | 98.2 | 100 |

For mecA-positive strains, MICs must be ≥0.5 μg/ml for proposed breakpoints or ≥4.0 μg/ml for current breakpoints to be considered correct; for mecA-negative strains, MICs must be ≤0.25 μg/ml for proposed breakpoints or ≤2.0 μg/ml for current breakpoints to be considered correct. MScan, MicroScan; S, susceptible; R, resistant.

Number given in parentheses is the total number of results used for calculations. Differences were due to growth failures in some MIC plates.

For the mecA-positive strains, most of the errors (i.e., those strains classified as susceptible by MIC testing) were limited to only a few strains. For example, all nine errors with the CDC Difco medium for mecA-positive S. epidermidis isolates resulted from problems with a single strain, S. epidermidis 42.

The major problem with the lower oxacillin breakpoints was the number of false-resistant results, i.e., mecA-negative strains classified as resistant by MIC testing. These were mainly CoNS other than S. epidermidis (Table 4). The errors represented difficulties in testing a variety of mecA-negative staphylococcal species, including S. warneri, S. capitis, S. lugdunensis, and S. saprophyticus, the oxacillin MICs for all these species tend to be higher than those for mecA-negative S. epidermidis strains. For these strains, the results of MIC testing were comparable among the 11 laboratories and were not skewed by the results of any single laboratory (data not shown).

Selection of disk diffusion breakpoints.

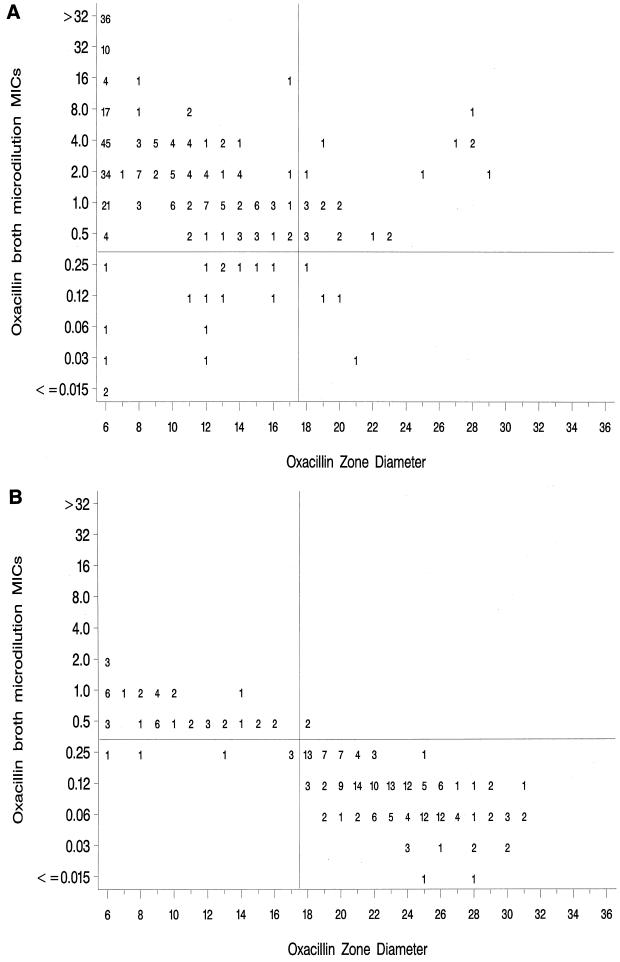

The scattergrams showing the MIC results with MicroScan BDMS Mueller-Hinton broth versus the disk diffusion zone diameter measurements obtained in each of the 11 laboratories for the 50 CoNS study isolates are shown in Fig. 1A (mecA-positive strains) and Fig. 1B (mecA-negative strains). The MicroScan BDMS broth values were selected for further analysis because they demonstrated the best correlation with the results of mecA testing (Table 3). By using the MIC breakpoints of ≤0.25 μg/ml for susceptibility and ≥0.5 μg/ml for resistance, disk diffusion breakpoints of ≤17 mm for resistance and ≥18 mm for susceptibility were chosen. Since the scattergram represents results of replicate testing of 50 isolates in 11 laboratories, true error rates cannot be calculated. However, of the 25 discordant results between MIC and disk diffusion testing in the upper right quadrants of Fig. 1 (those analogous to “very major errors”) that were determined by using MIC results (not mecA results), 23 results were for mecA-positive strains, 15 of which were due to two S. epidermidis strains, one S. simulans strain, and two S. hominis strains. Conversely, the “major errors” (lower left quadrants) were primarily due to a single mecA-positive S. epidermidis strain (strain 42) and the same S. hominis strains that caused the very major errors.

FIG. 1.

Scatterplots of oxacillin MICs versus oxacillin disk diffusion zone diameters for 50 CoNS tested in 11 laboratories. Proposed MIC and disk diffusion breakpoints are indicated by horizontal and vertical lines, respectively. (A) mecA-positive strains; (B) mecA-negative strains.

Figure 1B (upper left quadrant) shows several mecA-negative isolates that are classified both by MIC testing and by disk diffusion testing as resistant. The 41 results represent replicate testing of only four strains, i.e., one S. saprophyticus, one S. warneri, and two S. lugdunensis strains. The six values in the lower left quadrant of Fig. 1B are also results for S. warneri and S. lugdunensis strains.

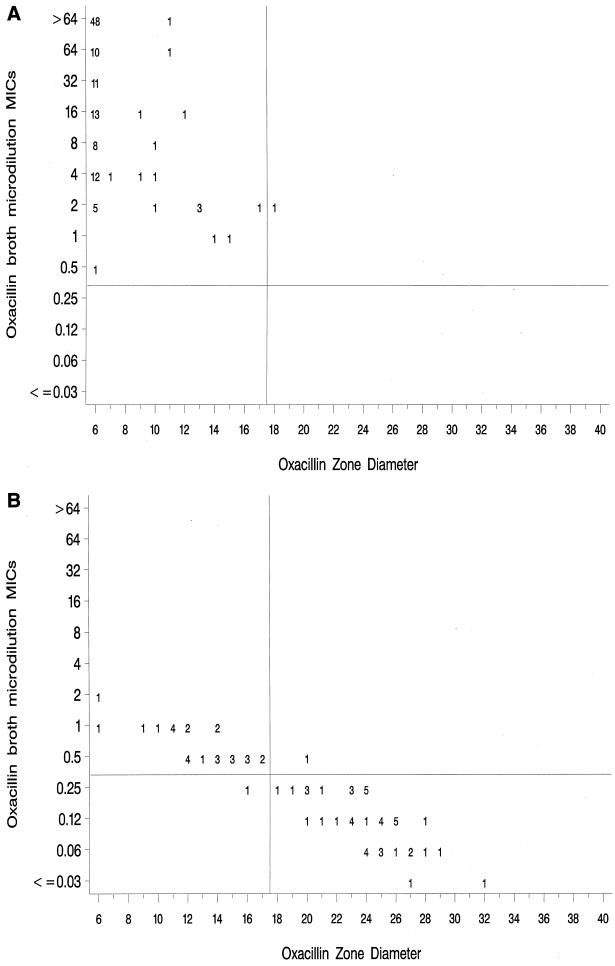

Since the isolates selected for this study were weighted towards organisms for which the oxacillin MICs are close to the current NCCLS breakpoint, the number of errors may be artificially high. To control for the potential impact of examining only organisms that were difficult to test, we applied the new MIC and disk diffusion breakpoints to a collection of CoNS isolates from five U.S. laboratories, tested over the last 5 years at CDC. Figure 2A (mecA-positive strains) and Fig. 2B (mecA-negative strains) show only two very major errors (one mecA-positive S. simulans strain and one mecA-negative S. haemolyticus strain) and one major error (one mecA-negative S. auricularis strain). However, 28 of 75 mecA-negative strains were classified as resistant by both the MIC and disk diffusion methods, including nine of nine S. lugdunensis strains, six of six S. saprophyticus strains, and mecA-negative strains of nine other staphylococcal species. None of the mecA-negative strains of S. epidermidis from the CDC data set were misclassified by using the proposed breakpoints.

FIG. 2.

Scatterplots of oxacillin MICs versus oxacillin disk diffusion zone diameters for 200 CoNS tested at CDC. Proposed MIC and disk diffusion breakpoints are indicated by horizontal and vertical lines, respectively. (A) mecA-positive strains; (B) mecA-negative strains.

Oxacillin agar screen test.

The results of the oxacillin agar screen tests are shown in Table 5. As expected, the tests with plates that were inoculated with a wet swab (higher inoculum) showed greater sensitivity in detecting mecA-positive strains than did those in which the liquid had been expressed from the swab prior to inoculation of the plate. However, even after 48 h of incubation, both commercial tests demonstrated unacceptably low sensitivities for mecA-positive strains. The Remel screening medium showed the highest sensitivity at 48 h for mecA-positive S. epidermidis strains (81.3%).

TABLE 5.

Correlation of mecA PCR test results with results of the oxacillin agar screen test

| Organism group (no. of test results) | % Correct results by oxacillin screen plate manufacturer and inoculation methoda

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remel

|

BDMS

|

|||||||

| Wet

|

Expressed

|

Wet

|

Expressed

|

|||||

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| S. epidermidis, mecA-positive (198) | 62.6 | 81.3 | 52.0 | 74.2 | 22.2 | 54.5 | 15.7 | 38.9 |

| Other species, mecA-positive (120) | 59.2 | 73.3 | 50.0 | 64.2 | 51.7 | 73.3 | 45.0 | 61.7 |

| S. epidermidis, mecA-negative (99) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.0 |

| Other species,bmecA-negative (129) | 98.5 | 97.7 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Percent correct results observed for each medium (growth for mecA-positive strains; no growth for mecA-negative strains). Wet, liquid was not expressed from the swab prior to inoculation of the agar screen plate; expressed, liquid was expressed from the swab prior to inoculation of the agar screen plate.

Data from three strains were deleted due to testing problems at one site.

DISCUSSION

Testing for oxacillin resistance in staphylococci has been a challenge for clinical laboratories for more than 15 years (11). Recently, several investigators have noted discrepancies between the results of MIC tests using the current NCCLS MIC breakpoint for oxacillin and the results of mecA assays (3, 9, 10, 17, 23). Based on these findings, they have suggested that the MIC susceptibility breakpoint for oxacillin should be lowered significantly below its current value of 2 μg/ml. However, the reasons for the poor correlation between MICs and the genetic assays used as the reference method were not enumerated in these reports. One of the goals of this study was to determine what factors may be responsible for the discrepancies between the phenotypic and genotypic results. In this regard, our data suggest that the source of Mueller-Hinton broth is one of the key factors that influence the oxacillin MIC results. Although Hindler and Warner reported several years ago that the source of Mueller-Hinton agar affected the results of the oxacillin screen test (5), the source of Mueller-Hinton broth apparently has not been considered to be a cause of discrepancies with broth microdilution MIC results. However, it is clearly not the only factor, since even the same lot of Difco medium gave statistically different oxacillin MIC results in panels prepared separately by two laboratories. Extensive review of the way in which both panels were prepared failed to reveal any substantial differences that could explain the variance in results. Both panels were supplemented, sterilized, and shipped in similar fashions. Although the MicroScan plates had V-shaped wells and the CDC plates had U-shaped wells, we do not think this can account for the differences observed. While the differences in results remain unresolved, we can conclude that part of the problem in previous reports of differences between MICs and mecA tests is likely to be medium related.

A second factor that influences MIC results is inoculum size. This study demonstrated that despite following the standard guidelines recommended by NCCLS, most of the participating laboratories unintentionally used an inoculum below the target concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml. This low inoculum was observed during testing of S. epidermidis isolates and a variety of other staphylococcal species. Given a typically low inoculum, it is not surprising that laboratories experienced problems with testing oxacillin, since many of the isolates tested are known to be heteroresistant and the number of daughter cells expressing the resistant phenotype may be less than 1 in 100,000 (4). While adjusting the inoculum suspension to a 1.0 McFarland standard to raise the actual inoculum size to the desired range may have been a reasonable suggestion prior to altering the breakpoints, with the proposed breakpoints, such an adjustment would only further contribute to the problem of classifying mecA-negative strains as resistant.

The proposed MIC breakpoints for oxacillin are lower than those advocated previously by York et al. (≤1 μg/ml for susceptibility) (23) and by Cormican et al. and McDonald et al. (both of whom proposed ≤0.5 μg/ml for susceptibility) (3, 10) but are consistent with those proposed by Marshall et al. (9). In our study, data from all of the above reports were taken into consideration. The breakpoints chosen appear to be the best choice for maximizing the sensitivity of detection of mecA-positive S. epidermidis isolates without severely compromising specificity. This approach was taken because S. epidermidis is the major CoNS species tested by clinical laboratories (2, 9, 22). However, for CoNS other than S. epidermidis, the proposed breakpoints are less effective in differentiating mecA-positive from mecA-negative strains (Table 4). Strains of several species for which the oxacillin MICs were 0.5 to 2.0 μg/ml were consistently mecA negative. Decreased susceptibility to oxacillin in these isolates may be due to alterations in penicillin binding proteins (PBPs) other than PBP2. For example, Suzuki et al. reported changes in PBPs 1 and 4 in several strains of methicillin-resistant, mecA-negative S. haemolyticus and S. saprophyticus (18). Whether strains of CoNS (other than S. epidermidis) for which oxacillin MICs were in the range of 0.5 to 2.0 μg/ml would be eradicated with penicillinase-resistant penicillins remains an open question. Until clinical data clarifying the relationship of mecA results and the results of phenotypic tests are available, laboratories may choose to use either the broth microdilution or the disk diffusion method for testing CoNS, since both produce comparable results.

This study is the first to examine the accuracy of the oxacillin agar screen plate as applied to CoNS in multiple laboratories. In contrast to some earlier reports (23), the test showed low sensitivity even when a larger inoculum was used (the wet swab) and the plate was incubated for 48 h. This observation suggests that use of the oxacillin agar screening method should be reserved exclusively for detecting mecA-positive S. aureus.

Having modified the oxacillin MIC breakpoints, we needed to adjust the disk diffusion breakpoints as well. York et al. reported discrepancies between the results of disk diffusion testing and mecA results, particularly with S. saprophyticus isolates (23). As noted above, in both the study data set and the CDC data set, several isolates of S. lugdunensis and S. saprophyticus, as well as strains of nine other staphylococcal species, were oxacillin resistant by both disk diffusion and MIC methods, yet consistently tested mecA negative. Thus, the phenotypic tests yielded consistent results but were discrepant from the genotypic results. While part of the problem may be a function of the challenge set of organisms selected for this study, which overrepresents staphylococci for which MICs are between 0.25 and 4.0 μg/ml and contains some rare phenotypes, the lack of correlation with the results of mecA testing for these species remains a concern. Although the proposed breakpoints functioned well when applied to the results published by others, the number of strains representing species other than S. epidermidis in those studies was small (3, 9).

In summary, the data presented here, in conjunction with data previously published by Marshall et al. (9) and others (3, 11, 23), prompted NCCLS to modify the oxacillin MIC breakpoints for testing CoNS to ≤0.25 μg/ml for susceptibility and ≥0.5 μg/ml for resistance. In addition, a single disk diffusion breakpoint of ≤17 mm for resistance and ≥18 mm for susceptibility was adopted. These breakpoints produce consistent results for MIC testing and disk diffusion testing but show disagreement with regard to some mecA-negative, non-S. epidermidis strains of staphylococci. Finally, due to its poor performance in this study, the oxacillin agar screen plate is no longer recommended by NCCLS for testing CoNS but is limited to testing S. aureus strains only.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank George Killgore and Mary Jane Ferraro for confirming the mecA results of the 50 strains and Michael Pfaller and Gary Doern for careful reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer G L, Pennell E. Detection of methicillin resistance in staphylococci by using a DNA probe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1720–1724. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cockerill F R, III, Hughes J G, Vetter E A, Mueller R A, Weaver A L, Ilstrup D M, Rosenblatt J E, Wilson W R. Analysis of 281,797 consecutive blood cultures performed over an eight-year period: trends in microorganisms isolated and the value of anaerobic culture of blood. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:403–418. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cormican M G, Wile W W, Barrett M S, Pfaller M A, Jones R N. Phenotypic detection of mecA-positive staphylococcal blood stream isolates: high accuracy of simple disk diffusion tests. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;25:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(96)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lancaster H, Figueiredo A M S, Tomasz A. Genetic control of population structure in heterogeneous strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:13–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02389872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindler J A, Warner N L. Effect of source of Mueller-Hinton agar on detection of oxacillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus using a screening methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:734–735. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.734-735.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang M B, Gay T E, Baker C N, Banerjee S N, Tenover F C. Two percent sodium chloride is required for susceptibility testing of staphylococci with oxacillin when using agar-based dilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2683–2688. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2683-2688.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kloos W E, Bannerman T L. Staphylococcus and Micrococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 282–298. [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacKenzie A M R, Richardson H, Lannigan R, Wood D. Evidence that the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards disk test is less sensitive than the screen plate for detection of low-expression-class methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1909–1911. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1909-1911.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall S A, Wilke W W, Pfaller M A, Jones R N. Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci from blood stream infections: frequency of occurrence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and molecular (mecA) characterization of oxacillin resistance in the SCOPE Program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:205–214. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald C L, Maher W E, Fass R J. Revised interpretation of oxacillin MICs for Staphylococcus epidermidis based on mecA detection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:982–984. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDougal L K, Thornsberry C. New recommendations for disk diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility tests for methicillin-resistant (heteroresistant) staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:482–488. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.4.482-488.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami K, Minamide W, Wada K, Nakamura E, Teraoka H, Watanabe S. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2240–2244. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2240-2244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed., vol. 17, no. 1. Approved standard M2-A6. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed., vol. 17, no. 2. Approved standard M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) report, data summary from October 1986–April 1996, issued May 1996. Am J Infect Control. 1996;24:380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson A C, Miorner H, Kamme C. Identification of mecA-related oxacillin resistance in staphylococci by the Etest and the broth microdilution method. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:445–456. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramotar K, Bobrowska M, Jessamine P, Toye B. Detection of methicillin-resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki E, Hiramatsu K, Yokota T. Survey of methicillin-resistant clinical strains of coagulase-negative staphylococci for mecA gene distribution. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:429–434. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.2.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenover F C, Popovic T, Olsvik Ø. Genetic methods for detecting antibacterial resistance genes. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 1368–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ubukata K, Nonoguchi R, Song M D, Matsuhashi M, Konno M. Homology of mecA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus and Staphylococcus simulans to that of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:170–172. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallet F, Roussel-Devallez M, Courcol R J. Choice of a routine method for detecting methicillin-resistance in staphylococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:901–909. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein M P, Towns M L, Quartey S M, Mirrett S, Reimer L G, Parmigiani G, Reller L B. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584–602. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.York M K, Gibbs L, Chehab F, Brooks G F. Comparison of PCR detection of mecA with standard susceptibility testing methods to determine methicillin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:249–253. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.249-253.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]