Abstract

The effectiveness of bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) in patients with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure (AHRF) due to etiologies other than chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is unclear. To systematically review the evidence regarding the effectiveness of BiPAP in non-COPD patients with AHRF. The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL Plus were searched according to prespecified criteria (PROSPERO-CRD42018089875). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effectiveness of BiPAP versus continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), invasive mechanical ventilation, or O2 therapy in adults with non-COPD AHRF were included. The primary outcomes of interest were the rate of endotracheal intubation (ETI) and mortality. Risk-of-bias assessment was performed, and data were synthesized and meta-analyzed where appropriate. Two thousand four hundred and eighty-five records were identified after removing duplicates. Eighty-eight articles were identified for full-text assessment, of which 82 articles were excluded. Six studies, of generally low or uncertain risk-of-bias, were included involving 320 participants with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema (ACPO) and solid tumors. No significant differences were seen between BiPAP ventilation and CPAP with regard to the rate of progression to ETI (risk ratio [RR] = 1.49, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–3.62, P = 0.37) and in-hospital mortality rate (RR = 0.71, 95% CI, 0.25–1.99, P = 0.51) in patients with AHRF due to ACPO. The efficacy of BiPAP appears similar to CPAP in reducing the rates of ETI and mortality in patients with AHRF due to ACPO. Further research on other non-COPD conditions which commonly cause AHRF such as obesity hypoventilation syndrome is needed.

Keywords: Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, bi-level positive airway pressure, endotracheal intubation, meta-analysis, mortality, noninvasive ventilation, systematic review

Acute respiratory failure (ARF), which generally results from insufficient gas exchange by the respiratory system,[1] is a significant disorder that can require invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) through endotracheal intubation (ETI) for its management.[2] In the 1990s, ARF was the most common indication for IMV among eight countries, accounting for more than 65% of ventilated patients.[2] Despite the high use of IMV due to improved survival rates,[3] IMV can cause many complications. ETI is associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP),[4] increased mortality rate,[4,5] IMV weaning difficulties, and increased health-care costs.[5] Therefore, noninvasive ventilation (NIV) has been increasingly used for acutely ill patients. NIV has many advantages, including a reduction in the risk of infection, a greater degree of patient co-operation and an increased ability to communicate,[6] as well as improvement in dyspnea.[7] Compared with IMV, NIV can achieve the same physiological outcomes of improved gas exchange and reduced work in breathing.[8] Moreover, NIV has a reduced incidence of side effects related to ETI and IMV, such as VAP, upper airway injuries, and excessive sedation. Thus, NIV has the potential to provide better clinical outcomes in certain patient groups.[9]

For several decades, NIV has been regarded as an effective method for avoiding the use of ETI and decreasing mortality in patients with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure (AHRF). Evidence supports the suggestion that the inclusion of NIV in a standard care strategy may enhance the outcomes in both patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation and patients with hypoxemic acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema (ACPO).[10,11] However, the effectiveness of bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) in AHRF due to etiologies other than COPD is still questioned. For instance, some of the studies of pulmonary edema did not exclude COPD patients,[12,13] so may not have proven NIV efficacy even in this group. Therefore, we performed a systematic review to determine the effectiveness of BiPAP in non-COPD patients with AHRF, using the need for ETI and the mortality rate after applying bi-level ventilation as the primary outcomes.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

The protocol for this systematic review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018089875). To identify the articles for the inclusion in this review, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library (Wiley interface), MEDLINE (Ovid interface), EMBASE (Ovid interface), and CINAHL Plus (EBSCO interface) were searched for relevant studies. In addition, trial registries (clinicaltrials.gov and WHO ICTRP) were used to search for ongoing and completed, but not yet published clinical trials. The bibliographies of the retrieved articles were reviewed to identify and conduct searches on related articles. Search terms are shown in the supplementary file [Appendix 1]. In brief, the inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which compared the effectiveness of BiPAP ventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), IMV, or oxygen therapy in adults with non-COPD AHRF. Effectiveness was determined by the comparison of the rates of the primary outcomes of interest, ETI, and mortality, between treatment groups.

Study selection

The reviewers independently made study selections based on titles and abstracts, which were compared against the inclusion criteria (lead reviewer – B. M. F., second reviewers – D. P., A. M. T., J. M., S. P. T.). Full texts were obtained after screening the titles and abstracts of potentially includable studies and conducting a similar dual-review process. Discussion between two reviewers and consultation with a third reviewer was done to resolve any concerns regarding the study selections.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (B. M. F. and S. P. T.) independently extracted the data from the included studies. The lead supervisor was consulted to resolve any disagreement regarding data extraction. The extracted information included study participant demographic data, study setting, study methodology, details of NIV used, and outcome measures [Appendix 2 in the supplementary file].

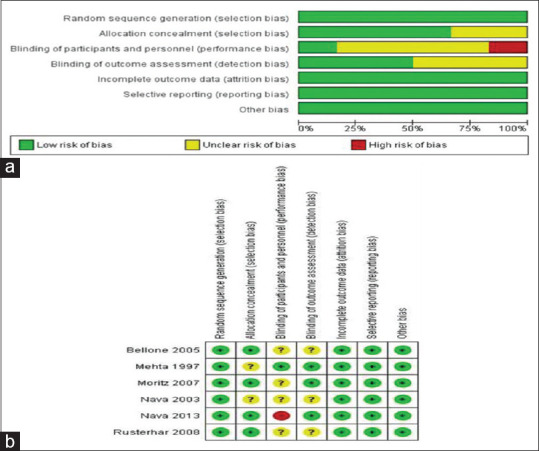

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the risk-of-bias tool in RevMan. This tool consists of the following six domains: Random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. Each domain was graded “yes,” “no,” or “unclear” to reflect a high or low risk of bias and uncertain bias, respectively. One reviewer (B. M. F.) completed the risk of bias assessment which was checked by a second reviewer (A. M. T.).

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest included the need for ETI and the mortality rate after applying BiPAP. The secondary outcomes of interest were length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, length of hospital stay, complications from treatment, and blood gas following the start of NIV.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive analyses are reported, and meta-analysis was performed using RevMan; pooled risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed and Chi-square test and I2 statistics were used to assess the heterogeneity of the study results. The heterogeneity was defined as low, moderate, and high with I2 values of >25%, >50%, and >75%, respectively. In the analysis of heterogeneity, a P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

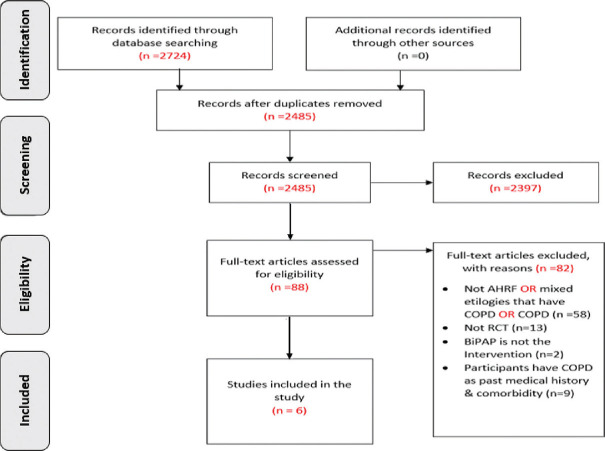

A total of 2485 records were identified through the database search after removing duplicates. Eighty-eight articles were identified for full-text assessment. Full-text reviews resulted in the exclusion of 82 studies for different reasons, as shown in Figure 1. The detailed included studies’ characteristics and the reasons for excluded studies are shown in Appendix 3 in the supplementary file.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Six articles were included in the study, involving 320 participants.[14,15,16,17,18,19] These included four RCTs comparing BiPAP to CPAP[14,15,16,17] and two comparing BiPAP to oxygen (O2) therapy.[18,19] All of the studies were RCTs using a parallel-group design. The six studies occurred in Italy,[15,18,19] the United States,[14] France,[16,17] Spain,[19] and Taiwan.[19] Four of the six articles were multicenter studies.[16,17,18,19] All reported on adult patients with AHRF due to ACPO[14,15,16,17,18] and malignancy.[19] The number of patients recruited in each study ranged from 27 to 100 with an average age of participants of 74.3 years; males and females accounted for 52% and 48% of the participants, respectively. Five studies reported intervention failure, demonstrated by the need for an ETI outcome, four studies compared intubation between BiPAP and CPAP[14,15,16,17] and one study compared intubation between BiPAP and O2.[18] In-hospital mortality was reported in almost all the studies; except for one study.[17] Three studies compared mortality between BiPAP and CPAP[14,15,16] and two studies between BiPAP and O2.[18,19] Table 2 shows the different IPAP, EPAP, and O2 levels and the choice of patient-ventilator interface. The risk of bias summary for the individual studies is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Disease | Participants (n) | Intervention (BiPAP) | Control | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehta (1997) | ACPO | 27 | 14 | CPAP=13 | ETI |

| Mortality rate | |||||

| LOS: Hospital and ICU | |||||

| Nava (2003) | ACPO | 64 | 33 | O2=31 | ETI |

| Mortality rate | |||||

| LOS: Hospital | |||||

| Bellone (2005) | ACPO | 36 | 18 | CPAP=18 | ETI |

| Mortality rate | |||||

| Moritz (2007) | ACPO | 57 | 29 | CPAP=28 | ETI |

| Mortality rate | |||||

| LOS: Hospital | |||||

| Rusterholtz (2008) | ACPO | 36 | 17 | CPAP=19 | ETI |

| Mortality rate | |||||

| LOS: ICU | |||||

| Nava (2013) | ESSD | 100 | 53 | O2=47 | Mortality rate |

ACPO=Acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, ETI=Endotracheal intubation, LOS=Length of stay, ICU=Intensive care unit, CPAP=Continuous positive airway pressure, ESSD=End-stage solid tumour, O2=Oxygen

Table 2.

Inspiratory positive airway pressure, expiratory positive airway pressure, and oxygen levels and patient-ventilator interface

| Study | IPAP (cm H2O) | EPAP (cm H2O) | CPAP (cm H2O) | O2 | Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellone (2005) | 15 | 5 | 10 | - | Face mask |

| Mehta (1997) | 14.35±1.73 | 5 | 10.08±1.24 | - | Nasal mask |

| Moritz (2007) | 12±3.2 | 4.9±0.9 | 7.7±2.1 | - | Facemask |

| Rusterholtz (2008) | - | 4 | 10 | - | Face mask |

| Nava (2003) | 14.5±21.1 | 6.1±3.2 | - | Not stated | Face mask |

| Nava (2013) | 10 | 5 | - | Face mask |

IPAP=Inspiratory positive airway pressure, EPAP=Expiratory positive airway pressure, CPAP=Continuous positive airway pressure, O2=Oxygen

Figure 2.

Summary of risk of bias in individual studies. (a) A graph with percentages for all included studies. (b) A summary of bias for each included study

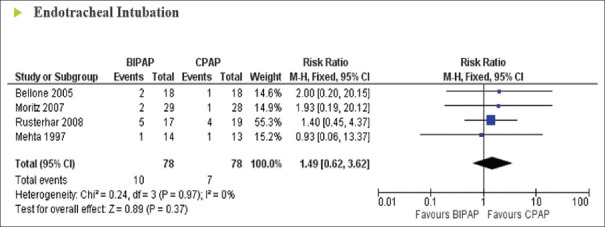

Endotracheal intubation

The results from four trials in ACPO (156 patients) were available for examining the effects of BiPAP vs CPAP on the incidence of ETI. A low level of heterogeneity was found among the identified comparisons (I2 = 0%; P = 0.97). Pooled analysis showed that the use of BiPAP was as effective as the control (CPAP) group with regard to the rate of intubation in hypercapnic respiratory failure patients, with no statistically significant difference between treatment groups (RR = 1.49; 95% CI: 0.62–3.62; P = 0.37) [Figure 3]. One study reported the effect of BiPAP vs O2 with respect to ETI; this study showed that the percentage of patients with BiPAP needing intubation was significantly lower in a hypercapnic sub-group.[18]

Figure 3.

Forrest plot comparing endotracheal intubation rates in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure patients treated with bi-level positive airway pressure compared to continuous positive airway pressure

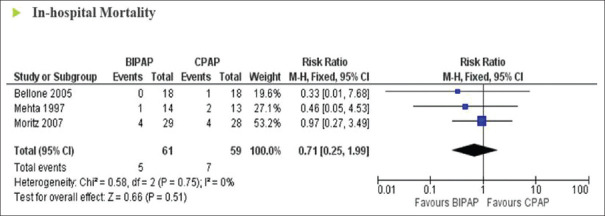

In-hospital mortality

In-hospital mortality was reported in three trials (120 patients) examining the effects of BiPAP versus CPAP on the incidence of in-hospital mortality in ACPO. A low level of heterogeneity was found (I2 = 0%; P = 0.75). Pooled analysis showed that BiPAP had no superior effect over CPAP with regard to the rate of in-hospital mortality (RR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.25–1.99; P = 0.51) [Figure 4]. In hypercapnic patients with end-stage tumor, patients with BiPAP had a better expected survival than patients receiving O2 alone.[19]

Figure 4.

Forrest plot comparing in-hospital mortality rates in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure patients treated with bi-level positive airway pressure compared to continuous positive airway pressure

Other outcomes

Two studies of BiPAP vs CPAP reported hospital length of stay as an outcome.[14,16] There were no significant differences in hospital length of stay observed between treatment groups in these studies. Bellone et al.[15] reported that there was a significant decrease in PaCO2 for both groups; however, other studies reported that the BiPAP group had greater reductions and significantly greater improvement in PaCO2 as compared to the control group.[14,18,19] Improvements in other physiological markers such as heart rate, blood pressure, pH, respiratory rate, and SpO2 were similar in trials comparing BiPAP to CPAP[15,16,17] and more significant in the BiPAP group when compared to O2 group.[18,19]

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates the effectiveness of using BiPAP in non-COPD patients with AHRF. The difference between BiPAP and CPAP or O2 was investigated, with regard to ETI and in-hospital mortality, and included studies generally showed little heterogeneity, perhaps due to our strict inclusion criteria. We were surprised to find that we were only able to meta-analyze studies of hypercapnic patients with ACPO, with a lack of RCTs for other hypercapnic non-COPD conditions. The number of studies using the treatment in ACPO was also lower than might be at first expected because many of the studies claiming to be treating a pulmonary edema population and included in prior systematic reviews,[20,21] in fact included high numbers of patients with coexistent COPD.[22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]

The European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have recommended the use of NIV in the treatment of acute heart failure,[31] so it would be beneficial to identify which of the ventilation modalities offers the optimal therapeutic benefit in patients with AHRF. Physiologically, BiPAP has a potential advantage over CPAP in reducing dyspnea and exhaustion by assisting the respiratory muscles in ACPO patients.[32] However, these physiological benefits did not translate into improved primary outcomes in our meta-analysis, which did not find any differences between BiPAP and CPAP with regard to ETI or in-hospital mortality. Nevertheless, hypercapnic patients, due to physiological reasons, were expected to benefit from BiPAP based on favorable results in some of the studies using BiPAP.[18,33] In hospitals where BiPAP is not available, however, CPAP would be a viable alternative based on the results.

Since the analysis was mainly based on an ACPO cohort, information on myocardial infarction (MI), which is an important cause of ACPO, was an important element to assess in our review. Overall, the incidence of MI was similar between the BiPAP and CPAP treatment groups in these studies. Although Mehta et al.’s study presented a higher rate of MI with BiPAP, Moritz et al.’s study also showed no significant differences in the incidence of MI when comparing BiPAP to CPAP. Moritz et al.’s findings were consistent with the other RCTs, as there were no differences between either technique on the incidence of MI.[22,27,34] This suggests that irrespective of the etiology of ACPO, whether it is due to MI or not, CPAP is equally effective as BiPAP and is safe to use.

The studies included in the review generally used IPAP, EPAP, and CPAP pressures that are not different from previous reviews on different hypercapnic conditions or the same condition but with different inclusion criteria. In addition, with regard to the NIV interfaces, most of the included studies used face mask interfaces which are consistent with the previous systematic reviews that reports the positive outcomes on hypercapnic respiratory failure patients.[20,35,36,37]

This meta-analysis is strengthened by its robust exclusion of coexistent COPD patients, such that we can be confident of the results with respect to conditions other than COPD. It also used a broad search strategy and multiple data sources, with no language restrictions, hence all available evidence was considered. However, it also has limitations. First, the sample size of the trials included in the meta-analysis was small, which could have underpowered our analysis of BiPAP compared to CPAP with regard to ETI and mortality. Second, a publication bias test was not performed due to the low number of included trials, and so these results should be viewed with caution.

Conclusion

Based on our systematic review and meta-analysis, we conclude that NIV reduces the incidence of intubation rate and mortality in hypercapnic patients with ACPO and that BiPAP appears equally effective as CPAP. This implies that patients with AHRF due to ACPO can be safely managed with CPAP, which is available in more non-ICU settings than BiPAP in most countries. For example, in the UK, CPAP is often available in coronary care units and acute medical units, whereas BiPAP is only available in specialized respiratory wards. This may aid patient flow through the hospital by opening up more locations in which such patients can be safely managed with taking in consideration healthcare providers’ experience and confidence with the management of the ARF. Further research is needed in this area which includes various other conditions which can cause AHRF, in particular obesity-hypoventilation. No RCTs of NIV in obesity-hypoventilation-related AHRF were seen, yet cohort studies suggest a beneficial effect[38] and sufficiently good in-hospital mortality[39] such that management in a ward-based setting may be preferable to the more costly and resource intensive ICU setting.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Search lists

| Medline search list |

|---|

| randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| randomized controlled trial.ti. |

| controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| randomized.ab. |

| trial.ab. |

| groups.ab. |

| 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| exp animals/not humans/ |

| 7 not 8 |

| exp Respiratory Insufficiency/ |

| respiratory failure.ti, ab. |

| Hypercapnia/ |

| acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.mp. |

| type II respiratory failure.mp. |

| (hypercap* or hypercarb* or pco2 or paco2).mp. |

| Neuromuscular Diseases/ |

| neuromuscular disease*.ti, ab. |

| exp Muscular Dystrophies/ |

| Muscular Disease*.mp. or exp Muscular Diseases/ |

| (neuromuscular adj 2 Disease*).mp. or exp neuromuscular junction diseases/ |

| exp Motor Neuron Disease/ |

| amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.ti, ab. |

| (Charcot disease or Lou Gehrig’s disease).ti, ab. |

| (charcot syndrome or Lou Gehrig’s syndrome).ti, ab. |

| exp Thoracic Diseases/or chest wall disorder*.ti, ab. |

| IMMUNOSUPPRESSION/ |

| exp IMMUNOCOMPROMISED HOST/ |

| Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome/or HIV Infections/or Immunologic Deficiency Syndromes/ |

| IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS/ |

| (immunocompromised or immunosuppressive or Immunodeficien* or immunosuppressed).mp. |

| exp ASTHMA/ |

| Respiratory Sounds/or wheez*.mp. |

| Bronchoconstriction/or bronchoconstrict*.mp. |

| Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome/ |

| obesity hypoventilation.ti, ab. |

| Pickwickian.mp. |

| OBESITY/ |

| exp Sleep Apnea, Obstructive/ |

| cardiogenic pulmonary edema.ti, ab. |

| Pulmonary Edema/ |

| (cardiogenic adj 2 edema*).ti, ab. |

| (pulmonary edema* or pulmonary oedema*).ti, ab. |

| wet lung.mp. |

| 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 |

| NONINVASIVE VENTILATION/ |

| NIV.mp. |

| Intermittent Positive-Pressure Ventilation/or Positive-Pressure Respiration/ |

| positive pressure ventilation.mp. |

| positive airway pressure.mp. |

| bipap.mp. |

| bilevel positive airway pressure.mp. |

| bi-level positive airway pressure.mp. |

| bilevel pressure ventilation.mp. |

| bi-level pressure ventilation.mp. |

| bilevel ventilation.mp. |

| bi-level ventilation.mp. |

| nippv.mp. |

| nppv.mp. |

| 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 |

| (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic obstructive airway disease or copd).ti. |

| 9 and 44 and 59 |

| 61 not 60 |

|

|

| EMBASE search list |

|

|

| randomized controlled trial.tw. |

| randomized controlled trial.ti. |

| controlled clinical trial.tw. |

| randomized.ab. |

| trial.ab. |

| groups.ab. |

| 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| exp animals/not humans/ |

| 7 not 8 |

| exp Respiratory Insufficiency/ |

| respiratory failure.ti, ab. |

| Hypercapnia/ |

| acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.mp. |

| type II respiratory failure.mp. |

| (hypercap* or hypercarb* or pco2 or paco2).mp. |

| Neuromuscular Diseases/ |

| neuromuscular disease*.ti, ab. |

| exp Muscular Dystrophies/ |

| Muscular Disease*.mp. or exp Muscular Diseases/ |

| (neuromuscular adj 2 Disease*).mp. or exp neuromuscular junction Diseases/ |

| exp Motor Neuron Disease/ |

| amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.ti, ab. |

| (Charcot disease or Lou Gehrig’s disease).ti, ab. |

| (charcot syndrome or Lou Gehrig’s syndrome).tw. |

| exp Thoracic Diseases/or chest wall disorder*.ti, ab. |

| IMMUNOSUPPRESSION/ |

| exp IMMUNOCOMPROMISED HOST/ |

| Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome/or HIV Infections/or Immunologic Deficiency Syndromes/ |

| IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS/ |

| (immunocompromised or immunosuppressive or Immunodeficien* or immunosuppressed).mp. |

| exp ASTHMA/ |

| Respiratory Sounds/or wheez*.mp. |

| Bronchoconstriction/or bronchoconstrict*.mp. |

| Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome/ |

| obesity hypoventilation.ti, ab. |

| Pickwickian.mp. |

| OBESITY/ |

| exp Sleep Apnea, Obstructive/ |

| cardiogenic pulmonary edema.ti, ab. |

| Pulmonary Edema/ |

| (cardiogenic adj 2 edema*).ti, ab. |

| (pulmonary edema* or pulmonary oedema*).ti, ab. |

| wet lung.mp. |

| 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 |

| NONINVASIVE VENTILATION/ |

| NIV.mp. |

| Intermittent positive-pressure ventilation/or positive-pressure respiration/ |

| positive pressure ventilation.mp. |

| positive airway pressure.mp. |

| bipap.mp. |

| bilevel positive airway pressure.mp. |

| bi-level positive airway pressure.mp. |

| bilevel pressure ventilation.mp. |

| bi-level pressure ventilation.mp. |

| bilevel ventilation.mp. |

| bi-level ventilation.mp. |

| nippv.mp. |

| nppv.mp. |

| 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 |

| (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic obstructive airway disease or copd).ti. |

| 9 and 44 and 59 |

| 61 not 60 |

| remove duplicates from 63 |

|

|

| Cochrane search list |

|

|

| Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) |

| #1 MeSH descriptor: [Respiratory Insufficiency] explode all trees |

| #2 (“respiratory failure”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #3 MeSH descriptor: [Hypercapnia] explode all trees |

| #4 (acute hypercapnic respiratory failure) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #5 MeSH descriptor: [Neuromuscular Diseases] explode all trees |

| #6 (Neuromuscular Disease) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #7 MeSH descriptor: [Muscular Dystrophies] explode all trees |

| #8 MeSH descriptor: [Muscular Diseases] explode all trees |

| #9 MeSH descriptor: [Neuromuscular Junction Diseases] explode all trees |

| #10 MeSH descriptor: [Motor Neuron Disease] explode all trees |

| #11 MeSH descriptor: [Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis] explode all trees |

| #12 (Charcot Disease) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #13 (Gehrig’s disease) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #14 MeSH descriptor: [Thoracic Diseases] explode all trees |

| #15 MeSH descriptor: [Immunocompromised Host] explode all trees |

| #16 (“immunocompromised”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #17 MeSH descriptor: [Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome] explode all trees |

| #18 MeSH descriptor: [Asthma] explode all trees |

| #19 MeSH descriptor: [Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome] explode all trees |

| #20 (“obesity hypoventilation”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #21 (“Pickwick Syndrome”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #22 MeSH descriptor: [Sleep Apnea, Obstructive] explode all trees |

| #23 (cardiogenic pulmonary edema) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #24 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23) in Trials |

| #25 MeSH descriptor: [Noninvasive Ventilation] explode all trees |

| #26 (NIV) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #27 MeSH descriptor: [Respiration, Artificial] explode all trees |

| #28 (“non-invasive ventilation”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #29 (“positive pressure ventilation”) OR (“positive pressure respiration”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #30 (“positive airway pressure”) (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #31 (“bi-level positive airway pressure”) OR (“bi-level positive airway pressure”):ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #32 (“NIPPV”) OR (nppv):ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) in Trials |

| #33 (#25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32) in Trials |

| #34 (#24 AND #33) in Trials |

|

|

| CINAHL plus search list |

|

|

| S1 (MH “Respiratory Failure”) |

| S2 (MH “Hypercapnia”) |

| S3 “acute hypercapnic respiratory failure” |

| S4 (MH “Neuromuscular Diseases”) |

| S5 (MH “Muscular Dystrophy, Duchenne”) |

| S6 (MH “Muscular Diseases”) |

| S7 (MH “Neuromuscular Junction Diseases”) |

| S8 (MH “Motor Neuron Diseases”) |

| S9 (MH “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis”) OR “ALS” |

| S10 “charcot disease” |

| S11 “gehrig’s disease” |

| S12 (MH “Thoracic Diseases”) OR “chest wall disorders” |

| S13 (MH “Immunosuppression”) OR (MH “Immunosuppressive Agents”) |

| S14 (MH “Immunocompromised Host”) |

| S15 (MH “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome”) OR “AIDS” |

| S16 (MH “Asthma”) |

| S17 (MH “Pickwickian Syndrome”) OR “obesity hypoventilation syndrome” |

| S18 (MH “Obesity”) |

| S19 (MH “Sleep Apnea, Obstructive”) |

| S20 (MH “Pulmonary Edema, Acute Cardiogenic”) OR (MH “Pulmonary Edema”) OR “cardiogenic pulmonary edema” |

| S21 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 |

| S22 (MH “Pressure Support Ventilation”) OR (MH “Positive Pressure Ventilation”) OR (MH “Noninvasive Procedures”) OR “noninvasive ventilation” |

| S23 “non invasive ventilation” OR “non-invasive ventilation” OR “NIV” |

| S24 (MH “Intermittent Positive Pressure Ventilation”) |

| S25 “bipap or nippv or bilevel positive airway pressure or noninvasive ventilators or mechanical ventilation or noninvasive positive pressure ventilators or respiration, artificial or pressure” |

| S26 “bilevel positive airway pressure” OR “bi-level positive airway pressure” OR “bipap” OR “nippv” OR “nppv” |

| S27 S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 |

| S28 S21 AND S27 |

Appendix 2: Data extraction form adapted from the Cochrane collaboration

| Reviewer ID | ||||||

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Study details | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Title | ||||||

| Country | ||||||

| Setting | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Author’s contact details | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Name | ||||||

| Institution | ||||||

| Address | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Additional data | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Year | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Methods | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Design | ||||||

| Group | ||||||

| Study design | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Population | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Inclusion criteria | ||||||

| Exclusion criteria | ||||||

| Group differences | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Interventions and comparisons | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Interventions | ||||||

| Comparisons | ||||||

| Outcomes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Results and conclusion | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Outcome names | Description | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Outcome names | Description | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Data analysis | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Result | Intervention | Comparison | ||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean/event | SD/% | Total number | Mean/event | SD/% | Total number | |

|

| ||||||

| Note | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Risk of bias | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Risk | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Random sequence generation | ||||||

| Allocation concealment | ||||||

| Blinding of participants and personnel | ||||||

| Blinding of outcome assessors | ||||||

| Incomplete outcome data | ||||||

| Selective reporting | ||||||

| Other sources of bias | ||||||

SD=Standard deviation

Appendix 3: Characteristics of included studies and reasons for excluded studies

| Characteristics of included studies | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mehta 1997 | ||

| Method | Randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Setting: Emergency department in a university hospital | |

| Participants | n=27 | |

| Interventions | Control: CPAP=13 | |

| Intervention: BiPAP=14 | ||

| Outcomes | Intubation rate | |

| length of time using BiPAP or CPAP | ||

| Length of ICU and hospital stays | ||

| Mortality rate | ||

| BP | ||

| HR | ||

| Breathing frequency | ||

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| Dyspnea score | ||

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

|

| ||

| Risk | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgment |

|

| ||

| Random sequence generation | Low | |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Low | |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Low | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | |

| Selective reporting | Low | |

| Other sources of bias | Low | |

CPAP=Continuous positive airway pressure, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, ICU=Intensive care unit, BP=Blood pressure, HR=Heart rate

| Nava 2003 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method | A multicenter randomized trial. Setting: Five emergency departments | |

| Participants | n=64 | |

| Interventions | Control: O2=31 | |

| Intervention: BiPAP=33 | ||

| Outcomes | Endotracheal intubation | |

| In-hospital mortality | ||

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| RR | ||

| Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | ||

| HR | ||

| Dyspnea | ||

| The duration of hospital stays | ||

| Cardiac enzymes | ||

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

|

| ||

| Risk | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgment |

|

| ||

| Random sequence generation | Low | |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | |

| Selective reporting | Low | |

| Other sources of bias | Low | |

RR=Respiratory rate, HR=Heart rate, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, O2=Oxygen

| Bellone 2005 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method | Controlled prospective randomized study. | |

| Setting: The Niguarda Hospital Emergency Department | ||

| Participants | n=36 | |

| Interventions | Control: CPAP=18 | |

| Intervention: BiPAP=18 | ||

| Outcomes | Endotracheal intubation | |

| In-hospital mortality | ||

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| RR | ||

| Resolution Time | ||

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

|

| ||

| Risk | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgment |

|

| ||

| Random sequence generation | Low | |

| Allocation concealment | Low | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | |

| Selective reporting | Low | |

| Other sources of bias | Low | |

CPAP=Continuous positive airway pressure, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, RR=Respiratory rate

| Moritz 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method | Prospective multicentre randomized study. Setting: Three Emergency Departments | |

| Participants | n=57 | |

| Interventions | Control: CPAP=28 | |

| Intervention: BiPAP=29 | ||

| Outcomes | Endotracheal intubation | |

| In-hospital mortality | ||

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| RR | ||

| The duration of hospital stays | ||

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

|

| ||

| Risk | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

|

| ||

| Random sequence generation | Low | |

| Allocation concealment | Low | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Low | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | |

| Selective reporting | Low | |

| Other sources of bias | Low | |

CPAP=Continuous positive airway pressure, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, RR=Respiratory rate

| Rusterholtz 2008 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method | A prospective multicentre randomized study. Setting: Three medical ICUs of three teaching hospitals | |

| Participants | n=36 | |

| Interventions | Control: CPAP=19 | |

| Intervention: BiPAP=17 | ||

| Outcomes | Endotracheal intubation | |

| In-hospital mortality | ||

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| RR | ||

| The duration of ICU stays | ||

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

|

| ||

| Risk | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgment |

|

| ||

| Random sequence generation | Low | |

| Allocation concealment | Low | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | |

| Selective reporting | Low | |

| Other sources of bias | Low | |

CPAP=Continuous positive airway pressure, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, RR=Respiratory rate, ICU=Intensive care unit

| Nava 2013 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method | Multicenter, stratified, randomized feasibility study. Setting: Five respiratory intensive care units and two critical care units of emergency departments | |

| Participants | n=100 | |

| Interventions | Control: O2=47 | |

| Intervention: BiPAP=53 | ||

| Outcomes | In-hospital mortality | |

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| RR | ||

| HR | ||

|

| ||

| Risk of bias | ||

|

| ||

| Risk | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgment |

|

| ||

| Random sequence generation | Low | |

| Allocation concealment | Low | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | High | Patients were not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Low | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | |

| Selective reporting | Low | |

| Other sources of bias | Low | |

O2=Oxygen, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure, RR=Respiratory rate, HR=Heart rate

Characteristics of excluded studies

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abou-shala (1996) | Not RCT |

| Antonelli (2000) | Not AHRF |

| Auriant (2001) | Not AHRF |

| Belenguer-muncharz (2017) | Not AHRF |

| Belenguer-muncharz (2017) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Bellone (2004) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Borel (2012) | Not AHRF |

| Bourke (2006) | Not AHRF |

| Brandao (2009) | Not BiPAP |

| Celikel (1998) | Not AHRF |

| Chadda (2002) | Not AHRF |

| Coimbra (2007) | Not AHRF |

| Confalonieri (1999) | Not AHRF |

| Coudroy (2016) | Not RCT |

| Crane (2004) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Cross (2003) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Cuomo (2004) | Not AHRF |

| Doshi (2018) | Not AHRF + mixed eti |

| Dumas (2017) | Not RCT |

| Eman (2015) | Not AHRF |

| Esteban (2004) | Not AHRF |

| Fartoukh (2010) | Not AHRF |

| Ferrari (2007) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Ferrari (2010) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Ferrer (2006) | Not AHRF |

| Ferrer (2009) | Not AHRF |

| Figueiredo (2016) | Not RCT |

| Gonzalez (2014) | Not RCT |

| Goodcare (2010) | Not AHRF |

| Gray (2009) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Gruis (2006) | not AHRF |

| Gupta (2010) | Not AHRF |

| Hanekom (2012) | Not AHRF |

| Hannan (2017) | Not RCT |

| Hazenberg (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Hetzenecher (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Ho (2006) | Not RCT |

| Holley (2001) | Not AHRF |

| Honrubia (2005) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Howard (2017) | Not AHRF |

| Hu (2011) | Not AHRF |

| Hui (2013) | Not AHRF |

| Iwama (2002) | Not AHRF |

| Jabber (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Jacobs (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Javaheri (2011) | Not AHRF |

| Jaye (2009) | Not AHRF |

| Jing (2013) | Not RCT |

| Kiehl (1996) | Not AHRF |

| Kramer (1995) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Lechtzin (2010) | Not RCT |

| Lee (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Lellouche (2014) | Not BiPAP |

| Lemiale (2015) | Not AHRF |

| Levitt (2001) | Not AHRF |

| Li (2013) | Not RCT |

| Liesching (2014) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Lopez-jimenez (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Luo (2014) | Not AHRF |

| Martin (2000) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Masa (2015) | Not AHRF |

| Masa (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Masa (2016) | Not AHRF |

| Masip (2000) | Past medical history of COPD |

| Momomura (2015) | Not AHRF |

| Moraes (2017) | Not AHRF |

| Moran (2003) | Not AHRF |

| Murphy (2012) | Not AHRF |

| Nava (2011) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Nouira (2011) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Park (2001) | Not AHRF |

| Park (2004) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Perazzo (2015) | Not RCT |

| Pinto (1995) | Not AHRF |

| Piper (2008) | Not AHRF |

| Roessler (2012) | Not AHRF |

| Sharon (2000) | Not AHRF |

| Soroksky (2003) | Not AHRF |

| Thys (2002) | Mixed etiologies including COPD |

| Udekwu (2017) | Not RCT |

| Wermke (2012) | Not RCT |

| Wysocki (1995) | Not AHRF |

RCT=Randomized controlled trials, AHRF=Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, COPD=Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, BiPAP=Bi-level positive airway pressure

References

- 1.Kacmarek RM, Stoller JK, Heuer A. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby, Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016. Egan' Fundamentals of Respiratory Care-E-Book. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteban A, Anzueto A, Alía I, Gordo F, Apezteguía C, Pálizas F, et al. How is mechanical ventilation employed in the intensive care unit? An international utilization review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1450–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9902018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson LD. Survival data in patients with acute and chronic lung disease requiring mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:S19–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.2_Pt_2.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres A, Aznar R, Gatell JM, Jiménez P, González J, Ferrer A, et al. Incidence, risk, and prognosis factors of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:523–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brochard L, Rauss A, Benito S, Conti G, Mancebo J, Rekik N, et al. Comparison of three methods of gradual withdrawal from ventilatory support during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:896–903. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nava S, Ambrosino N, Clini E, Prato M, Orlando G, Vitacca M, et al. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation in the weaning of patients with respiratory failure due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:721–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mas A, Masip J. Noninvasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:837–52. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S42664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitacca M, Ambrosino N, Clini E, Porta R, Rampulla C, Lanini B, et al. Physiological response to pressure support ventilation delivered before and after extubation in patients not capable of totally spontaneous autonomous breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:638–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2010046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bello G, De Pascale G, Antonelli M. Noninvasive ventilation for the immunocompromised patient: Always appropriate? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:54–60. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834e7c21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ram FS, Picot J, Lightowler J, Wedzicha JA. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for treatment of respiratory failure due to exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD004104. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Jindal SK. Non-invasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:637–43. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.031229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nouira S, Boukef R, Bouida W, Kerkeni W, Beltaief K, Boubaker H, et al. Non-invasive pressure support ventilation and CPAP in cardiogenic pulmonary edema: A multicenter randomized study in the emergency department. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:249–56. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park M, Sangean MC, Volpe Mde S, Feltrim MI, Nozawa E, Leite PF, et al. Randomized, prospective trial of oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure, and bilevel positive airway pressure by face mask in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2407–15. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000147770.20400.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta S, Jay GD, Woolard RH, Hipona RA, Connolly EM, Cimini DM, et al. Randomized, prospective trial of bilevel versus continuous positive airway pressure in acute pulmonary edema. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:620–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellone A, Vettorello M, Monari A, Cortellaro F, Coen D. Noninvasive pressure support ventilation vs.continuous positive airway pressure in acute hypercapnic pulmonary edema. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:807–11. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2649-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moritz F, Brousse B, Gellée B, Chajara A, L’Her E, Hellot MF, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure versus bilevel noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: A randomized multicenter trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:666–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.488. 675.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rusterholtz T, Bollaert PE, Feissel M, Romano-Girard F, Harlay ML, Zaehringer M, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure vs.proportional assist ventilation for noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:840–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-0998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nava S, Carbone G, DiBattista N, Bellone A, Baiardi P, Cosentini R, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in cardiogenic pulmonary edema: A multicenter randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1432–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1270OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nava S, Ferrer M, Esquinas A, Scala R, Groff P, Cosentini R, et al. Palliative use of non-invasive ventilation in end-of-life patients with solid tumours: A randomised feasibility trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:219–27. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vital FMR, Ladeira MT, Atallah ÁN. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005351.pub3. Art. No: CD005351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berbenetz N, Wang Y, Brown J, Godfrey C, Ahmad M, Vital FM, et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4:CD005351. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005351.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray AJ, Goodacre S, Newby DE, Masson MA, Sampson F, Dixon S, et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of the use of continuous positive airway pressure and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in the early treatment of patients presenting to the emergency department with severe acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: The 3CPO trial. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–06. doi: 10.3310/hta13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masip J, Betbesé AJ, Páez J, Vecilla F, Cañizares R, Padró J, et al. Non-invasive pressure support ventilation versus conventional oxygen therapy in acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2126–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liesching T, Nelson DL, Cormier KL, Sucov A, Short K, Warburton R, et al. Randomized trial of bilevel versus continuous positive airway pressure for acute pulmonary edema. J Emerg Med. 2014;46:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrari G, Olliveri F, De Filippi G, Milan A, Aprà F, Boccuzzi A, et al. Noninvasive positive airway pressure and risk of myocardial infarction in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Continuous positive airway pressure vs noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. Chest. 2007;132:1804–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrari G, Milan A, Groff P, Pagnozzi F, Mazzone M, Molino P, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure vs.pressure support ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: A randomized trial. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:676–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellone A, Monari A, Cortellaro F, Vettorello M, Arlati S, Coen D. Myocardial infarction rate in acute pulmonary edema: Noninvasive pressure support ventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1860–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139694.47326.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crane SD, Elliott MW, Gilligan P, Richards K, Gray AJ. Randomised controlled comparison of continuous positive airways pressure, bilevel non-invasive ventilation, and standard treatment in emergency department patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:155–61. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.005413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cross AM, Cameron P, Kierce M, Ragg M, Kelly AM. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure: A randomised comparison of continuous positive airway pressure and bi-level positive airway pressure. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:531–4. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belenguer-Muncharaz A, Mateu-Campos L, González-Luís R, Vidal-Tegedor B, Ferrándiz-Sellés A, Árguedas-Cervera J, et al. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure relating to cardiogenic pulmonary edema in an intensive care unit. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:561–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Members AT, McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:803–69. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wysocki M. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Better than continuous positive airway pressure? Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s001340050778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rusterholtz T, Kempf J, Berton C, Gayol S, Tournoud C, Zaehringer M, et al. Noninvasive pressure support ventilation (NIPSV) with face mask in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema (ACPE) Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:21–8. doi: 10.1007/s001340050782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrari G, Groff P, De Filippi G, Giostra F, Mazzone M, Potale G. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) vs.noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIV) in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema (ACPE): A prospective randomized multicentric study. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:246–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, Picot J, Wedzicha JA, Smith BJ. Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub4. Art. No: CD004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masip J, Roque M, Sánchez B, Fernández R, Subirana M, Expósito JA. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294:3124–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.24.3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moran F, Bradley JM, Piper AJ. Non-invasive ventilation for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002769.pub5. Art. No: CD002769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrillo A, Ferrer M, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Lopez-Martinez A, Llamas N, Alcazar M, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by obesity hypoventilation syndrome and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1279–85. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1101OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter R, Elhag S, Avent T, Chakraborty B, Oakes A, Antoine-Pitterson P, et al. Non-invasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure unrelated to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 2018. Lung Breath J. 2 DOI: 10.15761/LBJ.1000129. [Google Scholar]