Abstract

Human African trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness, results from infection by two subspecies of the protozoan flagellate parasite Trypanosoma brucei, termed Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, prevalent in western and eastern Africa respectively. These subspecies escape the trypanolytic potential of human serum, which efficiently acts against the prototype species Trypanosoma brucei brucei, responsible for the Nagana disease in cattle. We review the various strategies and components used by trypanosomes to counteract the immune defences of their host, highlighting the adaptive genomic evolution that occurred in both parasite and host to take the lead in this battle. The main parasite surface antigen, named Variant Surface Glycoprotein or VSG, appears to play a key role in different processes involved in the dialogue with the host.

Current Opinion in Immunology 2021, 72:13–20

This review comes from a themed issue on Host pathogen

Edited by Helen C Su and Jean-Laurent Casanova

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

Available online 12th March 2021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2021.02.007

0952-7915/© 2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

;1;

Introduction

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense are respectively responsible for a chronic and an acute form of sleeping sickness, the first being widespread in western and central Africa, and the second in eastern and southern Africa. While humans are regarded as the main reservoir for T.b. gambiense transmission, human infection by T.b. rhodesiense only occurs occasionally. As both trypanosome species are transmitted by Glossina (tsetse) flies, the risk of sleeping sickness is determined by the occurrence of contacts between humans and infected tsetse flies. In 1998, almost 40 000 cases were reported, but it is estimated that 300 000 cases were undiagnosed and therefore untreated (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness). Trypanosomiasis in domestic animals (Nagana) is also a very serious animal health issue that impacts on animal mortality, growth and productivity with consequent negative impacts on socio-economic development throughout sub-Sharan Africa.

Growing successively in Glossina flies and mammalian hosts, African trypanosomes have developed complex mechanisms for molecular adaptations to quite different environments [1]. Among the various factors involved in these adaptations, the organization of the surface membrane is particularly important to counteract both innate and adaptive responses of the host. Contrary to strategies used by other pathogens to evade host surveillance, such as antigen mosaicism characteristic of the American trypanosome Trypanosoma cruzi, antigenic variation in African trypanosomes involves periodic changes of a uniform, densely packed coat containing 107 copies of a single antigen called VSG, which covers the entire parasite surface including the flagellum.

The sole site for membrane traffic to/from the surface is the flagellar pocket, a specialized invagination of the surface membrane at the base of the flagellum. The pocket membrane is coated with VSG, but also contains various surface receptors whose elongated structure allows insertion within this coat [2,3].

T. brucei infection begins in the skin, where the parasites interact with adipocytes and neutrophils [4], and then follows in the bloodstream, where the dialogue with the immune system can persist in long-lasting chronic infection. Whereas T. brucei-triggered innate immunity involves strong inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses notably due to carbohydrate components of the VSG such as high-mannose [5,6], adaptive immunity mainly involves antibodies directed against VSG epitopes [7]. In addition, efficient human innate immunity is conferred by the primate-specific trypanolytic factor Apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) [8].

APOL1 trypanolytic activity

Unlike the other five members of the APOL family, which are intracellular proteins, APOL1 is a serum protein bound to high-density lipoprotein particles [9]. In these particles APOL1 is associated with a protein related to haptoglobin (haptoglobin-related protein, or Hpr), which like Hp can bind hemoglobin (Hb). This complex, termed Trypanosome Lytic Factor 1 or TLF1, may be associated with germline IgMs, which recognize pathogen signatures such as high-mannose carbohydrates, and accumulate upon infection [10••,11]. This IgM-associated TLF1 is called TLF2 [10••]. TLF1 uptake occurs through Hpr/Hb binding to the Hp/Hb receptor TbHpHbR, normally responsible for providing growth-promoting heme to the parasite [12], whereas uptake of TLF2 involves non-specific IgM binding to VSG [10••,11]. Because of competition between Hpr/Hb and Hp/Hb, TLF1 uptake is only efficient in the absence of HpHb, such as occurs in extravascular environments like the skin at the beginning of infection, or in hypohaptoglobinemic serum [13]. In contrast, TLF2 uptake is unaffected by the presence of HpHb, and probably represents the major physiological mode of APOL1 uptake by bloodstream parasites [10••,11, 12, 13]. In both cases APOL1 moves through the endocytic system, and generates endolysosomal ionic pores due to acidic pH-dependent membrane insertion [14, 15, 16, 17]. Subsequent transfer of APOL1-containing membranes to the mitochondrion by the C-terminal kinesin TbKIFC1 triggers trypanolysis [14]. This occurs through mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and release of the mitochondrial TbEndoG endonuclease to the nucleus, which cleaves DNA into nucleosomal units as occurs during apoptosis in higher eukaryotes [14]. It was hypothesized that APOL1-carrying endosomes also recycle to the plasma membrane, inducing cation conductance that disrupts ionic homeostasis [15,16]. However, the presence of APOL1 in the plasma membrane, as well as the mechanism for this transport, have not been demonstrated so far.

Trypanosome resistance to APOL1

The two possible modes of resistance to APOL1, either APOL1 inactivation or resistance to APOL1 activity, have been respectively developed by the two distinct T. brucei clones that can infect humans [11]. In the case of T.b. rhodesiense, the specific Serum-Resistance Associated protein (SRA) binds to the C-terminal helix of APOL1, thereby inhibiting the APOL1 pore-forming activity [8,18]. Interestingly, SRA is derived from a VSG that acquired the ability to interact with APOL1 through truncation of its surface-exposed domain and resulting localization to endocytic compartments instead of the cell surface [11,19]. High SRA expression is required for T.b. rhodesiense resistance to APOL1, probably explaining why the SRA gene is transcribed by the highly processive RNA polymerase I, rather than the usual RNA polymerase II [20].

Resistance of T.b. gambiense to APOL1 involves another VSG-derived protein termed T. gambiense-specific glycoprotein, or TgsGP [11,21]. This protein stiffens endosomal membranes where APOL1 should normally insert during its journey within the trypanosome, therefore hindering APOL1 pore-forming activity [21]. However, TgsGP-mediated protection cannot resist high APOL1 uptake occurring in the absence of HpHb, such as in hypohaptoglobinemic serum [21]. Given that human adaptation to malaria is linked to frequent hypohaptoglobinemia in Western Africa, T.b. gambiense probably adapted to this condition by limiting APOL1 uptake through L210S mutation in TbHpHbR, which reduces the affinity for the ligand [21]. Thus, T.b. gambiense likely responded to a human adaptation to another parasite, Plasmodium, illustrating an unexpected dialogue between parasites through the host.

The APOL1 arms race

Given the direct interaction of SRA with the C-terminal helix of APOL1, experimental disruption of this helix by mutagenesis can allow APOL1 to escape neutralization by SRA, enabling these APOL1 C-terminal variants to kill T.b. rhodesiense [18]. Interestingly, such C-terminal APOL1 variants, able to kill T.b. rhodesiense, were found to be naturally widespread in Western Africa [22]. These variants, termed G1 and G2, are respectively characterized by two separate mutations and a double amino acid deletion in the APOL1 C-terminal helix. Their abundance in Western Africa could possibly account for the disappearance of T. rhodesiense from this part of the continent [11]. Thus, G1 and G2 allowed humans to restore their lead in the resistance to African trypanosomes, except for T.b. gambiense.

However, like resistance to malaria is linked to sickle cell anemia, the price to pay for resistance to sleeping sickness is a propensity to develop chronic kidney disease [22].

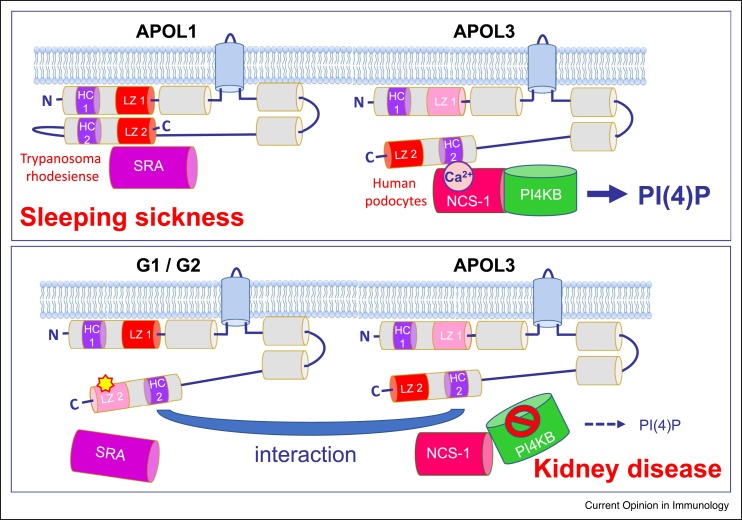

The mechanism allowing G1 and G2 to cause kidney disease has been debated for years [23]. While many studies pointed to non-specific cytotoxicity of G1 and G2, a recent report concluded that cytotoxicity is due to APOL1 overexpression, and that the disease results from unfolding of an intracellular isoform of the G1/G2 variants, triggering their interaction with APOL3 [24••]. Such interaction inactivates APOL3-mediated stimulation of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate [PI(4)P] synthesis by the Golgi kinase PI4KB [24••] (Figure 1). The reduction of PI(4)P levels in G1/G2-expressing podocytes would account for the increased mobility and reduced autophagy that characterize podocytes of kidney disease patients [24••,25]. Interestingly, a non-sense variant of APOL3 was found to exhibit positive selection in African populations, while also causing nephropathy like the APOL1 G1/G2 variants [26]. Because of its inability to be secreted, APOL3 cannot kill bloodstream trypanosomes despite its intrinsic lytic potential [17]. Since the interaction of APOL1 variants with APOL3 leads to inactivation of both partners [24••], the selective advantage of APOL3 KO could result from the loss of APOL3-mediated neutralization of the trypanolytic APOL1 variants.

Figure 1.

APOL1 C-terminal variants that escape neutralization by T.b. rhodesiense SRA cause kidney disease through inactivation of APOL3.

A schematic structure model is presented for intracellular APOL1 isoform 3 (top panel: wild-type; bottom panel: G1 or G2 variants) and APOL3, as they could be inserted in Golgi membrane of human podocytes [9,24••]. Grey and blue cylinders respectively represent α-helices and transmembrane spans. Contrary to APOL3, APOL1 is folded through cis-interactions between N-terminal and C-terminal helices that each contain a cluster of hydrophobic amino acids (hydrophobic cluster, or HC) and a leucine zipper (LZ) (red or pink LZ colour: respectively strong or weak coiled-coiling potential). Whereas in T.b. rhodesiense APOL1 LZ2 interacts with the APOL1-neutralizing parasite protein SRA, in human podocytes APOL3 HC2 exhibits Ca2+-dependent interaction with neuronal calcium sensor (NCS-1), thereby promoting PI4KB interaction with NCS-1, which stimulates the synthesis of PI(4)P [9,24••]. C-terminal mutations in LZ2, such as occurs for the G1 and G2 variants (yellow asterisk in bottom panel), allow APOL1 to escape the neutralizing interaction with SRA, therefore protecting humans against T.b. rhodesiense infection (sleeping sickness). However, the G1 or G2 mutations also trigger interaction of intracellular APOL1 variants with APOL3, which inactivates both APOL1 and APOL3 and interferes with APOL3 binding to NCS-1, leading to reduction of PI(4)P synthesis by PI4KB. Reduction of PI(4)P levels leads to reorganization of actomyosin activity, susceptible to account for podocyte dysfunctions linked to G1/G2-dependent kidney disease [9,24••,25]. The positive selection of APOL3 KO recently observed in the genome of African populations [26] could result from the loss of G1/G2 inactivation by APOL3 [24••].

Early parasite defences: the key roles of motility and TbKIFC1

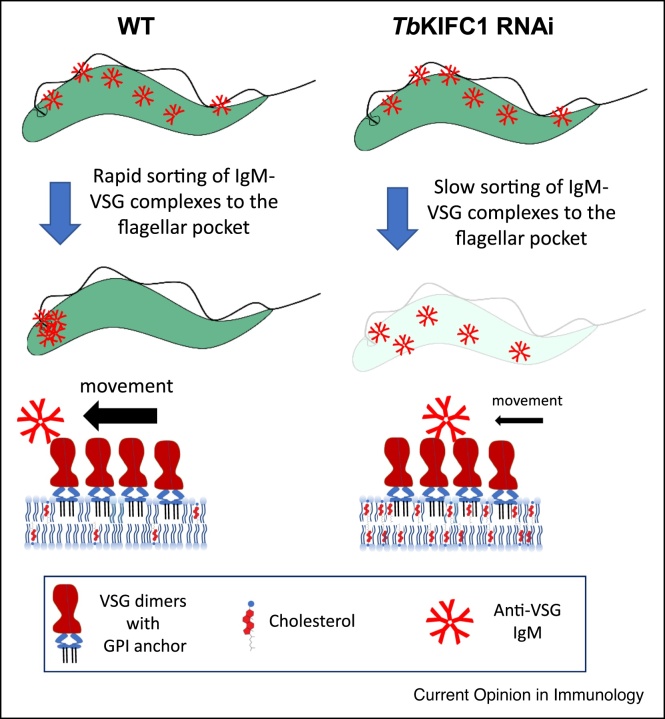

In the skin, neutrophils are rapidly recruited to the site of infection, which paradoxically facilitates the development of trypanosome colonization [4,27]. Indeed, trypanosomes efficiently resist the neutrophil-mediated engulfment and elimination [27]. This faculty is linked to parasite motility following TatD DNase-mediated disruption of neutrophil extracellular DNA traps [28], and trypanosomes completely lacking propulsive motility cannot infect mice despite efficient clearance of antibody-VSG complexes [29]. Conversely, reduction of the rate of antibody-VSG clearance in motile trypanosomes fully prevents infection [30••]. The fast clearance results from lateral mobility of the glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol-anchored VSG, linked to high plasma membrane fluidity ensured by the cholesterol-trafficking activity of the TbKIFC1 kinesin [30••]. Thus, fast antibody clearance is absolutely required for trypanosome infectivity, and TbKIFC1 is an essential virulence factor needed for this purpose (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

TbKIFC1 downregulation confers more sensitivity to antibody-mediated lysis.

The cholesterol-trafficking activity of TbKIFC1 contributes to high plasma membrane fluidity, conferring resistance to IgM-mediated killing through efficient clearance of VSG-antibody complexes from the parasite surface [30••]. Following TbKIFC1 RNAi, trypanosomes are lyzed due to slower clearance of antibody-VSG complexes from the surface.

Paradoxically, the requirement of TbKIFC1 for clearance of IgM-VSG complexes is also likely to be the driving force for TLF2 internalization, and thus trypanosome killing, because TLF2 IgMs bind to the VSG [10••,11]. Therefore, as also occurs for TLF1-associated APOL1 uptake, which is linked to the capture of the growth factor heme, TLF2-associated APOL1 uptake may depend on a mechanism normally intended to help trypanosome survival, and thus could be another version of the Trojan horse story.

The parasite armoury against innate immunity: parasite-released factors

Trypanosome infection triggers the rapid synthesis of inflammatory components such as TNF-α and reactive nitrogen/oxygen species like nitric oxide (NO) [4]. The precise role of TNF-α in infection has been controversial. This cytokine is important for parasite control at the beginning of infection, and yet trypanosome growth is unaffected in established infections despite considerable induction of TNF-α synthesis. This paradox probably results from the fact that only membrane-bound TNF-α affects the parasite [31]. Counteracting this inflammatory response in early stages of infection appears to be the role of the multiple receptor-like adenylate cyclases (ACs) of the parasite [32]. Internalization of AC-containing trypanosome membranes into macrophages, through phagocytosis of either entire parasites [32] or released extracellular vesicles [33], promotes the synthesis of cyclic AMP that reduces TNF-α synthesis through activation of protein kinase A within macrophages [32]. Thus, lyzed trypanosomes or vesicles released from the surface of live trypanosomes can condition macrophages to stop synthesizing TNF-α early in infection. Similarly, a released kinesin heavy chain (TbKHC1) can condition myeloid cells to synthesize the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, thereby stimulating the growth-promoting activity of arginase-1 and conversely inhibiting the anti-parasite activity of NO synthase [34].

Trypanosomes also secrete metabolites that modulate host responses, which may be especially important within the central nervous system. Trypanosomes constitutively secrete aromatic ketoacids such as indole pyruvate, which inhibit production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β by macrophages [35]. Moreover, these metabolites additionally supress IL-6 and TNF-α production by glial cells, and are potent inducers of heme oxygenase 1, an activity associated with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant pathways [36]. These effects may orchestrate pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses to produce a ‘chemical lullaby’ within the host, to lessen systemic pathologies associated with persistent infection. Such long-lasting infection is required for the transfer of trypanosomes between hosts, given their inefficient mode of transmission through the tsetse fly.

The parasite strategy against adaptive immunity: VSG variation

Antigenic variation and subsequent anti-VSG responses continuously limit infection, contributing to shape chronic infection. Not only VSG sequence variation resulting from total or partial gene replacement, but also variable post-translational VSG modifications such as O-glycosylation, contribute to antibody escape [37]. Antigenic variation requires monoallelic expression of the VSG: from a repertoire of several hundred VSG genes, only one is expressed at any one time. Failure to follow this rule prevents successful infection due to inefficient antibody escape [38]. This requirement is ensured by the existence of only one VSG expression site body (ES body) in the nucleus. Experimental generation of two simultaneously active VSG ES results in their dynamic colocalization within a single ES body [39]. The molecular machinery underlying the maintenance of a single ES body has been the subject of intense research, with the recent observations that factors such as histone variants or the telomere-binding protein RAP1 and its binding component PI(3,4,5)P3 delineate transcriptionally active versus inactive VSG ES in subtelomeric chromatin domains [40, 41, 42]. However, presumably the most significant breakthrough in this field was the discovery of a new protein complex responsible for allelic exclusion, containing the chromatin VSG-exclusion-1 (VEX1) protein and VEX2, an ortholog of the nonsense-mediated-decay helicase UPF1 [43,44••]. VEX1 and VEX2 assemble in an RNA polymerase-I transcription-dependent manner, and following DNA replication VEX1 compartmentalisation in the ES body is specifically maintained by the DNA replication-associated chromatin assembly factor CAF-1 [44••]. More specifically, productive monogenic VSG mRNA synthesis was found to result from spatial coupling between VEX1 in the mRNA splicing locus and VEX2 in the VSG-coding locus [45••], explaining how functional transcription in the active VSG ES depends on the selective recruitment of an RNA elongation/processing machinery [46,47].

Moreover, VSG ES inactivation was found to involve components of a transcription termination complex recruited to base J, a specific thymine modification linked to transcription silencing [48•]. In addition to these factors, SNF2PH, a SUMOylated plant homeodomain (PH)-transcription factor, promotes bloodstream-specific transcription [49].

Changing the selected VSG ES to another in the ES body is a mechanism triggering antigenic variation, and this can result from DNA damage frequently observed in the VSG ES due to its open chromatin configuration and high transcription rate. Indeed, in the ES body the repeats flanking the VSG gene are transcribed into long-noncoding RNAs that form RNA:DNA hybrids (R-loops), and if not removed by RNase H these R-loops cause double-strand breaks that increase VSG ES switching [50, 51, 52, 53, 54]. Importantly, the mechanism linking DNA damage to VSG ES switching was found to involve ATR, a DNA damage-signalling protein kinase [55••]. ATR loss was found to alter the localization of both RNA polymerase I and VEX1 [55••]. Furthermore, a putative translesion DNA polymerase able to bypass telomeric DNA damage, termed TbPolIE, was also found to be involved in the control of antigenic variation [56].

In addition to VSG ES switching, DNA recombination such as gene conversion occurring between the active VSG gene and any other silent VSG gene can trigger antigenic variation [51,57]. Given the involvement of homologous recombination in this process, the order of VSG switching is influenced by the relative level of sequence homology between the donor and target gene [57]. However, two recent observations complicate this view. At least during early infection, the VSG hierarchy appears to be also dependent on the VSG size [58]. Presumably due to the increased metabolic cost of producing longer VSGs, the growth rate of trypanosomes expressing shorter VSGs favours their accumulation during switching to new VSGs. Subsequent elimination of fast-growing trypanosomes then allows slower-growing parasites with longer VSGs to accumulate [58]. Another relevant observation pertains to the mechanism of antigenic variation in the T. brucei-related trypanosome Trypanosoma vivax, a livestock pathogen. In this parasite, recombination plays little role in diversifying VSG sequences [59]. How this parasite manages nevertheless to develop antigenic variation is unclear.

The parasite strategy against adaptive immunity: variation and shielding of surface receptors

The best characterized receptors for growth factors in bloodstream forms of T. brucei are those for transferrin (TbTfR) and Hp-Hb (TbHpHbR), respectively responsible for iron and heme uptake [3,12,60,61•]. Recently, a receptor for mammalian factor H (TbFHR), only expressed in tsetse-transmissible and fly gut forms, has been characterised [62]. All of these receptors possess a three-helical fold that allows for an elongate structure compatible with the densely packed VSG coat. In all cases, the binding site is present at the membrane distal end, ensuring that it is accessible to macromolecular ligands. Either N-glycosylation (TbTfR) or a structural kink (TbHpHbR) is thought to prevent molecular crowding of the receptor by VSGs, and facilitates ligand access to the binding site. Given the necessary exposure at the cell surface, these receptors must have evolved mechanisms to escape antibody detection. Given the reported receptor affinities and concentrations of circulating ligand, receptor saturation may render the exposed binding site inaccessible to antibody. This is certainly the case for TbTfR and TbFHR [60,61•] and possibly for TbHpHbR [3,11,13]. Since the TbTfR is encoded by a collection of different VSG-like genes present in the various VSG ESs, antigenic variation of this receptor occurs upon VSG ES switching [47,60,63]. However, recent structural studies suggest that immune avoidance is the driving force for TbTfR diversification. In accordance with early studies demonstrating the influence of polymorphic surface-exposed sites on ligand affinity [63], it was concluded that variable regions are the most exposed to immune detection, and that N-linked glycans serve to shield a large part of the membrane-distal region not involved in ligand binding [61•].

Conclusions

Not surprisingly, African trypanosomes have developed multiple mechanisms to counteract the host defences (Table 1). At the beginning of infection, a combination of swimming motility and membrane fluidity is necessary for the parasite to avoid immediate elimination due to the early recruitment of neutrophils and induction of germline IgMs. The response to innate immunity involves the release of various anti-inflammatory parasite components, possibly through the shedding of extracellular vesicles. Many pathogens, for example, Anaplasma, Borrelia, Neisseria, Mycoplasma and Plasmodium, employ antigenic variation as an evasion strategy, but in African trypanosomes this system has evolved to an extreme level [64], probably because only extensive antigenic variation allows long-lasting chronic infection, which is vital for successful transmission to the insect vector. Trypanosome antigenic variation necessitates the activity of many factors ensuring both monoallelic VSG expression and continuous changes of selectively activated VSG gene. Despite the complexity of this system, major progresses have been performed during the period of this review, with the identification of several key actors and the precise identification of their mode of action. Structural studies have also revealed answers to the longstanding issue of how parasite receptors for macromolecules can interact with their ligand without being vulnerable to antibody attack. Finally, in the case of human infection, the particular story of the trypanolytic factor APOL1 has revealed how parasites and host can entertain a continuous arms race with price to pay on both sides. Clearly, studying the dialogue between trypanosomes and humans largely extends beyond the fields of parasitology and immunology.

Table 1.

Mechanisms allowing African trypanosomes to evade host immunity

| Host defence components | Parasite response | |

|---|---|---|

| Specific innate immunity | - Human serum toxin (APOL1) targeted to the parasite through different Trojan horse strategies (VSG and TbHpHbR) [10••,11, 12, 13] | - APOL1 neutralization (T. rhodesiense SRA) [8]; - Resistance to APOL1 (T. gambiense TgsGP) [21] |

| - APOL1 C-terminal G1/G2 variants, which resist SRA of T. rhodesiense [22,24••] | - Replacement of T. rhodesiense by T. gambiense in western Africa [11] | |

| - APOL3 nonsense variant, relieving APOL3-mediated G1/G2 inactivation [26,24••] | ||

| General innate immunity | - Neutrophil DNA traps | - DNA cleavage (TatD DNases) [28] - Parasite motility (flagellum) [29] |

| - Germline IgMs | - High membrane fluidity ensuring fast clearance of IgM-VSG complexes (TbKIFC1) [30••] | |

| - Inflammatory response (TNF-α, NO, IL-1β, IL-6) |

- Inhibition of early TNF-α synthesis (adenylate cyclases) [32] - NO synthase inhibition (TbKHC1) [34] - IL-1β/IL-6 inhibition (indole pyruvate) [35,36] |

|

| Adaptive immunity | - Anti-VSG IgGs | - High membrane fluidity ensuring fast clearance of IgG-VSG complexes (TbKIFC1) [30••] - VSG antigenic variation (VEX1/VEX2: expression site selection; ATR: expression site switching) [44••,45••,55••] |

| - Antibodies against invariant surface receptors | - Receptor embedding within the VSG coat [3,61•] - Receptor saturation shielding the ligand site - N-glycan coating - Antigenic variation of surface-exposed regions [63] |

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC 669007-APOLs to E.P.) and the Wellcome Trust and Science Foundation Ireland (SFI to D.P.N.).

References

- 1.Szöőr B., Silvester E., Matthews K.R. Leap into the unknown - early events in African trypanosome transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwede A., Macleod O.J.S., MacGregor P., Carrington M. How does the VSG coat of bloodstream form African trypanosomes interact with external proteins? PLoS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins M.K., Lane-Serff H., MacGregor P., Carrington M. A receptor’s tale: an eon in the life of a trypanosome receptor. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mabille D., Caljon G. Inflammation following trypanosome infection and persistence in the skin. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020;66:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stijlemans B., De Baetselier P., Magez S., Van Ginderachter J.A., De Trez C. African Trypanosomiasis-associated anemia: the contribution of the interplay between parasites and the mononuclear phagocyte system. Front Immunol. 2018;9:218. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Trez C., Stijlemans B., Bockstal V., Cnops J., Korf H., Van Snick J., Caljon G., Muraille E., Humphreys I.R., Boon L., et al. A critical Blimp-1-dependent IL-10 regulatory pathway in T cells protects from a lethal pro-inflammatory cytokine storm during acute experimental Trypanosoma brucei infection. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1085. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinger J., Chowdhury S., Papavasiliou F.N. Variant surface glycoprotein density defines an immune evasion threshold for African trypanosomes undergoing antigenic variation. Nat Commun. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00959-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanhamme L., Paturiaux-Hanocq F., Poelvoorde P., Nolan D.P., Lins L., Van den Abbeele J., Pays A., Tebabi P., Xong H.V., Jacquet A., et al. Apolipoprotein L-I is the trypanosome lytic factor of human serum. Nature. 2003;422:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature01461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pays E. The function of Apolipoproteins L (APOLs): relevance for kidney disease, neurotransmission disorders, cancer and viral infection. FEBS J. 2021;288:360–381. doi: 10.1111/febs.15444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10••.Verdi J., Zipkin R., Hillman E., Gertsch R.A., Pangburn S.J., Thomson R., Papavasiliou N., Sternberg J., Raper J. Inducible germline IgMs bridge trypanosome lytic factor assembly and parasite recognition. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First evidence that germline IgMs are induced by infection, and proposal of a mechanism for TLF2 uptake in the parasite.

- 11.Pays E., Vanhollebeke B., Uzureau P., Lecordier L., Pérez-Morga D. The molecular arms race between African trypanosomes and humans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:575–584. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanhollebeke B., Demuylder G., Nielsen M.J., Pays A., Tebabi P., Dieu M., Raes M., Moestrup S.K., Pays E. A haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptor conveys innate immunity to Trypanosoma brucei in humans. Science. 2008;320:677–681. doi: 10.1126/science.1156296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanhollebeke B., Pays E. The trypanolytic factor of human serum: many ways to enter the parasite, a single way to kill. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:806–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanwalleghem G., Fontaine F., Lecordier L., Tebabi P., Klewe K., Nolan D.P., Yamaryo-Botté Y., Botté C., Kremer A., Schumann Burkard G., et al. Coupling of lysosomal and mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in trypanolysis by APOL1. Nat Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson R., Finkelstein A. Human trypanolytic factor APOL1 forms pH-gated cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers: relevance to trypanosome lysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2894–2899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421953112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaub C., Verdi J., Lee P., Terra N., Limon G., Raper J., Thomson R. Cation channel conductance and pH gating of the innate immunity factor APOL1 is governed by pore lining residues within the C-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:13138–13149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.014201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fontaine F., Lecordier L., Vanwalleghem G., Uzureau P., Van Reet N., Fontaine M., Tebabi P., Vanhollebeke B., Büscher P., Pérez-Morga D., et al. APOLs with low pH dependence can kill all African trypanosomes. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:1500–1506. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecordier L., Vanhollebeke B., Poelvoorde P., Tebabi P., Andris F., Lins L., Pays E. C-terminal mutants of apolipoprotein L-I efficiently kill both Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoll S., Lane-Serff H., Mehmood S., Schneider J., Robinson C.V., Carrington M., Higgins M.K. The structure of serum resistance-associated protein and its implications for human African trypanosomiasis. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:295–301. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecordier L., Uzureau P., Tebabi P., Brauner J., Benghiat S., Vanhollebeke B., Pays E. Adaptation of Trypanosoma rhodesiense to hypohaptoglobinemic serum requires transcription of the APOL1 resistance gene in a RNA polymerase I locus. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97:397–407. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uzureau P., Uzureau S., Lecordier L., Fontaine F., Tebabi P., Homblé F., Grélard A., Zhendre V., Nolan D., Lins L., et al. Mechanism of Trypanosoma gambiense resistance to human serum. Nature. 2013;501:430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genovese G., Friedman D.J., Ross M.D., Lecordier L., Uzureau P., Freedman B.I., Bowden D.W., Langefeld C.D., Oleksyk T.K., Uscinski, Knob A.L., et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman D.J., Pollak M.R. APOL1 and kidney disease: from genetics to biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020;82:323–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021119-034345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24••.Uzureau S., Lecordier L., Uzureau P., Hennig D., Graversen J.H., Homble F., Mfutu P.E., Oliveira Arcolino F., Ramos A.R., La Rovere R.M., et al. APOL1 C-terminal variants may trigger kidney disease through interference with APOL3 control of actomyosin. Cell Rep. 2020;30:3821–3836. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First hint of the APOL function, and explanation of the mechanism of kidney disease induction by APOL1 C-terminal variants.

- 25.Pays E. The mechanism of kidney disease due to APOL1 risk variants. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:2502–2505. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020070954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rausell A., Luo Y., Lopez M., Seeleuthner Y., Rapaport F., Favier A., Stenson P.D., Cooper D.N., Patin E., Casanova J.-L., et al. Common homozygosity for predicted loss-of-function variants reveals both redundant and advantageous effects of dispensable human genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:13626–13636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917993117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caljon G., Mabille D., Stijlemans B., De Trez C., Mazzone M., Tacchini-Cottier F., Malissen M., Van Ginderachter J.A., Magez S., De Baetselier P., et al. Neutrophils enhance early Trypanosoma brucei infection onset. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang K., Jiang N., Chen H., Zhang N., Sang X., Feng Y., Chen R., Chen Q. TatD DNases of African trypanosomes confer resistance to host neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci China Life Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1854-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimogawa M.M., Ray S.S., Kisalu N., Zhang Y., Geng Q., Ozcan A., Hill K.L. Parasite motility is critical for virulence of African trypanosomes. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9122. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27228-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Lecordier L., Uzureau S., Vanwalleghem G., Deleu M., Crowet J.M., Barry P., Moran B., Voorheis P., Dumitru A.C., Yamaryo Y., et al. The Trypanosoma brucei KIFC1 kinesin ensures the fast antibody clearance required for parasite infectivity. iScience. 2020;23 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First experimental evidence that fast clearance of VSG-antibody complexes is required for trypanosome infectivity, and demonstration that membrane fluidity necessary for this clearance is controlled by TbKIFC1-dependent removal of cholesterol.

- 31.Vanwalleghem G., Morias Y., Beschin A., Szymkowski D.E., Pays E. Trypanosoma brucei growth control by TNF in mammalian hos is independent of the soluble form of the cytokine. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6165. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06496-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmon D., Vanwalleghem G., Morias Y., Denoeud J., Krumbholz C., Lhomme F., Bachmaier S., Kador M., Gossmann J., Dias F.B., et al. Adenylate cyclases of Trypanosoma brucei inhibit the innate immune response of the host. Science. 2012;337:463–466. doi: 10.1126/science.1222753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szempruch A.J., Sykes S.E., Kieft R., Dennison L., Becker A.C., Gartrell A., Martin W.J., Nakayasu E.S., Almeida I.C., Hajduk S.L., et al. Extracellular vesicles from Trypanosoma brucei mediate virulence factor transfer and cause host anemia. Cell. 2016;164:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Muylder G., Daulouede S., Lecordier L., Uzureau P., Morias Y., Van Den Abbeele J., Caljon G., Herin M., Holzmuller P., Semballa S., et al. A Trypanosoma brucei kinesin heavy chain promotes parasite growth by triggering host arginase activity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGettrick A.F., Corcoran S.E., Barry P.J., McFarland J., Crès C., Curtis A.M., Franklin E., Corr S.C., Mok K.H., Cummins E.P., et al. Trypanosoma brucei metabolite indolepyruvate decreases HIF-1α and glycolysis in macrophages as a mechanism of innate immune evasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E7778–E7787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608221113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell N.K., Williams D.G., Fitzgerald H.K., Barry P.J., Cunningham C.C., Nolan D.P., Dunne A. Trypanosoma brucei secreted aromatic ketoacids activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and suppress pro-inflammatory responses in primary murine glia and macrophages. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2137. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinger J., Nešić D., Ali L., Aresta-Branco F., Lilic M., Chowdhury S., Kim H.-S., Verdi J., Raper J., Ferguson M.A.J., et al. African trypanosomes evade immune clearance by O-glycosylation of the VSG surface coat. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:932–938. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0187-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aresta-Branco F., Sanches-Vaz M., Bento F., Rodrigues J.A., Figueiredo L.M. African trypanosomes expressing multiple VSGs are rapidly eliminated by the host immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:20725–20735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905120116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Budzak J., Kerry L.E., Aristodemou A., Hall B.S., Witmer K., Kushwaha M., Davies C., Povelones M.L., et al. Dynamic colocalization of 2 simultaneously active VSG expression sites within a single expression-site body in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:16561–16570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905552116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller L.S.M., Cosentino R.O., Förstner K.U., Guizetti J., Wedel C., Kaplan N., Janzen C.J., Arampatzi P., Vogel J., Steinbiss S., et al. Genome organization and DNA accessibility control antigenic variation in trypanosomes. Nature. 2018;563:121–125. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afrin M., Kishmiri H., Sandhu R., Rabbani M.A.G., Li B. Trypanosoma brucei RAP1 has essential functional domains that are required for different protein interactions. mSphere. 2020;5 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00027-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cestari I., McLeland-Wieser H., Stuart K. Nuclear phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphatase is essential for allelic exclusion of variant surface glycoprotein genes in trypanosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00395-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glover L., Hutchinson S., Alsford S., Horn D. VEX1 controls the allelic exclusion required for antigenic variation in trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:7225–7230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600344113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Faria J., Glover L., Hutchinson S., Boehm C., Field M.C., Horn D. Monoallelic expression and epigenetic inheritance sustained by a Trypanosoma brucei variant surface glycoprotein exclusion complex. Nat Commun. 2019;10 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10823-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discovery and characterization of the molecular complex at the origin and maintenance of the VSG ES body, which conditions monoallelic expression of the VSG.

- 45••.Faria J., Luzak V., Müller L.S.M., Brink B.G., Hutchinson S., Glover L., Horn D., Siegel T.N. Spatial integration of transcription and splicing in a dedicated compartment sustains monogenic antigen expression in African trypanosomes. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:289–300. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00833-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evidence that spatial coupling between transcription and transcript processing underlies monoallelic VSG expression, a key component of antigenic variation.

- 46.Vanhamme L., Poelvoorde P., Pays A., Tebabi P., Xong H.V., Pays E. Differential RNA elongation controls the variant surface glycoprotein gene expression sites in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:328–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pays E., Vanhamme L., Pérez-Morga D. Antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei: facts, challenges and mysteries. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48•.Kieft R., Zhang Y., Marand A.P., Moran J.D., Bridger R., Wells L., Schmitz R.J., Sabatini R. Identification of a novel base J binding protein complex involved in RNA polymerase II transcription termination in trypanosomes. PLoS Genet. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Characterization of components of the multimeric transcription termination complex that controls VSG ES inactivation through its recruitment to telomeric DNA containing the modified thymine base J.

- 49.Saura A., Iribarren P.A., Rojas-Barros D., Bart J.M., López-Farfán D., Andrés-León E., Vidal-Cobo I., Boehm C., Alvarez V.E., Field M.C., et al. SUMOylated SNF2PH promotes variant surface glycoprotein expression in bloodstream trypanosomes. EMBO Rep. 2019;20 doi: 10.15252/embr.201948029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos da Silva M., Hovel-Miner G.A., Briggs E.M., Elias M.C., McCulloch R. Evaluation of mechanisms that may generate DNA lesions triggering antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sima N., McLaughlin E.J., Hutchinson S., Glover L. Escaping the immune system by DNA repair and recombination in African trypanosomes. Open Biol. 2019;9 doi: 10.1098/rsob.190182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saha A., Nanavaty V.P., Li B. Telomere and subtelomere R-loops and antigenic variation in trypanosomes. J Mol Biol. 2020;432:4167–4185. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Briggs E., Crouch K., Lemgruber L., Hamilton G., Lapsley C., McCulloch R. Trypanosoma brucei ribonuclease H2A is an essential R-loop processing enzyme whose loss causes DNA damage during transcription initiation and antigenic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:9180–9197. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Briggs E., Crouch K., Lemgruber L., Lapsley C., McCulloch R. Ribonuclease H1-targeted R-loops in surface antigen gene expression sites can direct trypanosome immune evasion. PLoS Genet. 2018;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55••.Black J.A., Crouch K., Lemgruber L., Lapsley C., Dickens N., Tosi L.R.O., Mottram J.C., McCulloch R. Trypanosoma brucei ATR links DNA damage signaling during antigenic variation with regulation of RNA polymerase I-transcribed surface antigens. Cell Rep. 2020;30:836–851. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Identification of a kinase linking DNA damage in the transcriptionally active VSG ES with the control of VSG ES switching in the ES body.

- 56.Leal A.Z., Schwebs M., Briggs E., Weisert N., Reis H., Lemgruber L., Luko K., Wilkes J., Butter F., McCulloch R., et al. Genome maintenance functions of a putative Trypanosoma brucei translesion DNA polymerase include telomere association and a role in antigenic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:9660–9680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pays E. Pseudogenes, chimaeric genes and the timing of antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Trends Genet. 1989;5:389–391. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu D., Albergante L., Newman T.J., Horn D. Faster growth with shorter antigens can explain a VSG hierarchy during African trypanosome infections: a feint attack by parasites. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10922. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29296-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silva Pereira S., de Almeida Castilho Neto K.J.G., Duffy C.W., Richards P., Noyes H., Ogugo M., Rogério André M., Bengaly Z., Kemp S., Teixeira M.M.G., et al. Variant antigen diversity in Trypanosoma vivax is not driven by recombination. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14575-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kariuki C.K., Stijlemans B., Magez S. The trypanosomal transferrin receptor of Trypanosoma brucei-a review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4:126. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4040126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61•.Trevor C.E., Gonzalez-Munoz A.L., Macleod O.J.S., Woodcock P.G., Rust S., Vaughan T.J., Garman E.F., Minter R., Carrington M., Higgins M.K. Structure of the trypanosome transferrin receptor reveals mechanisms of ligand recognition and immune evasion. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:2074–2081. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0589-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Detailed structural study addressing the puzzling mechanism of surface receptor escape from antibody detection.

- 62.MacLeod O.J.S., Bart J.-M., MacGregor P., Peacock L., Savill N.J., Hester S., Ravel S., Sunter J.D., Trevor C., Rust S., et al. A receptor for the complement regulator factor H increases transmission of trypanosomes to tsetse flies. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salmon D., Hanocq-Quertier J., Paturiaux-Hanocq H., Nolan D., Pays A., Tebabi P., Michel A., Pays E. Characterization of the ligand-binding site of the transferrin receptor in Trypanosoma brucei demonstrates a structural relationship with the N-terminal domain of the variant surface glycoprotein. EMBO J. 1997;16:7272–7278. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCulloch R., Cobbold C.A., Figueiredo L., Jackson A., Morrison L.J., Mugnier M.R., Papavasiliou N., Schnaufer A., Matthews K. Emerging challenges in understanding trypanosome antigenic variation. Emerg Top Life Sci. 2017;1:585–592. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20170104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]