Last year, Helsinki, Finland, and Oslo, Norway, announced a stunning accomplishment: after decades of sustained effort, both densely populated capital cities recorded zero deaths among cyclists and pedestrians in 2019.1 Their achievement is remarkable proof that efficient urban mobility need not come at the cost of human lives. It also stands in stark contrast to the lackluster traffic safety record of similarly sized municipalities in the United States. How can American cities close the gap to their European counterparts? The Vision Zero framework provides one roadmap by which urban America might navigate toward safer streets.

Originating in Sweden in 1995, Vision Zero rejects the conventional transportation planning paradigm that makes trade-offs between road user safety and considerations such as traffic flow, driver expectations, and cost. Instead, Vision Zero embraces a simple premise: the only acceptable number of serious traffic injuries is zero.2 Under this framework, policymakers, road users, city traffic engineers, urban planners, law enforcement, and vehicle manufacturers work together to design a transportation system that tolerates human error, minimizes crash risk, and mitigates the risk of injury even if a crash occurs.2 As demonstrated in Oslo and Helsinki, this often means using protected bicycle lanes and pedestrian bridges to separate vulnerable road users from vehicles, controlling vehicle speed with chicanes and speed humps, preventing head-on collisions with median barriers, and decreasing kinetic energy transfer at potential collision sites using modern roundabouts.2 Between 2010 and 2017, these and other interventions reduced pedestrian fatalities by 23% in Finland and by 54% in Norway, yet pedestrian deaths increased by 38% in the United States over the same period.3

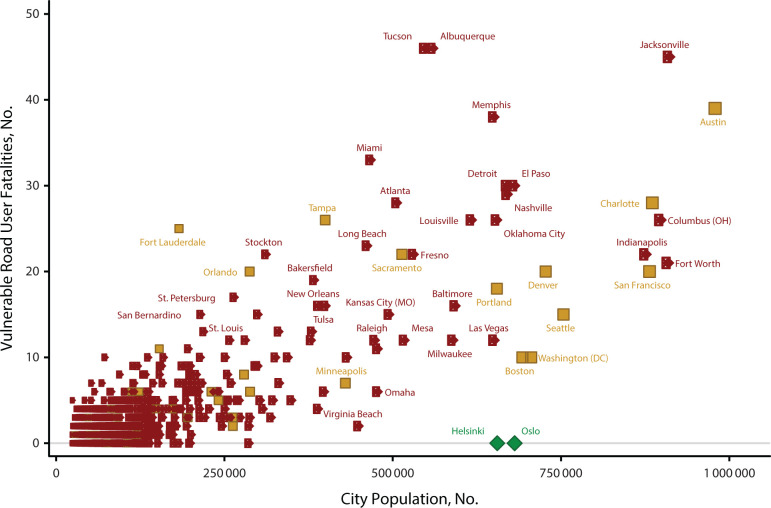

While American cities might have something to learn from their Scandinavian counterparts, the striking variability in vulnerable road user fatality rates across urban America suggests that many US cities can also learn from successes closer to home (Figure 1). Boston, Massachusetts, and Seattle, Washington, for example, have publicly committed to Vision Zero. To make progress toward a goal of zero traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2030, the City of Seattle performed a data-driven bicycle and pedestrian safety analysis to help prioritize intersection safety improvements, developed a safety-focused transportation master plan, standardized speed limits on most residential streets (nonarterial, 20 miles per hour [mph]; arterial, 25 mph), expanded the use of red-light cameras and other forms of traffic safety enforcement, accelerated the installation of leading pedestrian intervals (in which the “walk” signal is illuminated three to seven seconds before the vehicle green light, enhancing pedestrian visibility), created a crash review task force, and committed millions of dollars to enhance a cycling network that will include almost 200 miles of protected bike lanes and greenways.7 The City of Boston struck an interdisciplinary Vision Zero Task Force, created a Vision Zero Action Plan, lowered the default speed limit on city streets from 30 mph to 25 mph, curtailed vehicle speeds in some residential neighborhoods using speed humps and curb extensions, opened sight lines and installed leading pedestrian intervals to improve pedestrian visibility at select intersections, made capital investments in bicycle lane safety, and committed to periodically publishing crash data that allow citizens to hold city decisionmakers accountable.8 It would be naïve to suggest simple causality, but these two cities have 65% fewer vulnerable road user fatalities per capita than Detroit, Michigan; Memphis, Tennessee; or El Paso, Texas—similarly sized US cities that have yet to commit to Vision Zero.

FIGURE 1—

Vulnerable Road User Fatalities in US Cities in 2019

Note. Scatterplot depicting the number of pedestrian and cyclist fatalities for 1513 US cities with a population between 25 000 and 1 million residents. X-axis indicates the city population; y-axis indicates the number of traffic fatalities in 2019; dot size indicates the city population; circles indicate US cities outside of the Vision Zero Network; squares indicate US cities within the Vision Zero Network; diamonds indicate Nordic cities.4‒6 American cities with fewer than 1 million residents account for 82% of all US urban vulnerable road user fatalities. An analogous figure including all cities with more than 25 000 residents can be found in the Appendix (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

New York City’s experience since adopting the Vision Zero framework in 2014 refutes the common misconception that traffic safety interventions are unacceptably costly. Vision Zero principles motivated ambitious and wide-ranging changes to traffic safety legislation, education, engineering, and enforcement, culminating in an impressive 33% reduction in pedestrian fatalities over the first six years of the initiative.9 One inexpensive and highly effective legislative intervention reduced the default speed limit from 30 to 25 mph for the vast majority of city streets, producing a 39% reduction in injuries and fatalities on affected roadways.10 An analysis using data from the New York City Department of Transportation concluded that protected bike lanes are highly cost effective (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $1297 per quality-adjusted life year gained, far below the conventional $50 000 per quality-adjusted life year willingness-to-pay threshold for medical interventions).11 Similar analyses using empirical data found that Neighborhood Slow Zones and speed limit enforcement cameras save money and save lives.12,13 Instead of portraying traffic safety interventions as an onerous expense, US cities might find Vision Zero initiatives are more politically palatable when framed as both an ambitious American “moon shot” and a financially prudent investment.

While larger, densely populated American cities individually report the highest absolute number of traffic deaths, efforts to reduce urban road risks should also focus on less populous urban areas. Though this strategy seems counterintuitive, it illustrates a form of the prevention paradox: half of America’s urban vulnerable road user fatalities occur in cities smaller than Mobile, Alabama (population 189 809).14 Smaller cities and towns often lack the resources and experience to make progress against Vision Zero targets, suggesting that state governments may need to supply capital and expertise to enable rapid reductions in road morbidity and mortality. Progress in smaller cities could be accelerated by evidence-informed safety-focused changes to state speed, seatbelt, and impaired driving laws, and by removal of state-level restrictions on photo-radar speed enforcement, automated red-light cameras, and random sobriety checkpoints.15

The elimination of pedestrian and cyclist fatalities in two European capitals is a giant leap toward the ambitious eradication of all types of serious traffic injury. Relentless application of Vision Zero principles has allowed Helsinki and Oslo to lead the way. Now it is time for American cities to catch up.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant 20R76785), the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, and the University of British Columbia Division of General Internal Medicine.

Note. Funding organizations were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

POST PUBLICATION UPDATE

When originally published, Figure 1 on page 1587 displayed an incorrect shape for the red data points. The figure was updated to correctly display red circles. An erratum has since been issued indicating the change.

References

- 1.Zero cyclist and pedestrian deaths in Helsinki and Oslo last year. European Traffic Safety Council. February 11, 2020https://etsc.eu/zero-cyclist-and-pedestrian-deaths-in-helsinki-and-oslo-last-year [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim E, Muennig P, Rosen Z. Vision Zero: a toolkit for road safety in the modern era. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40621-016-0098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Transport Forum: Road safety annual report 2019. Paris, France: International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group, International Transport Forum, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2019. https://www.nhtsa.gov/research-data/fatality-analysis-reporting-system-fars

- 5.US Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010-2019/cities/totals/sub-est2019_all.csv

- 6.Vision Zero Network. San Francisco, CA: Vision Zero Network; 2018. https://visionzeronetwork.org/resources/vision-zero-cities [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seattle Department of Transportation, City of Seattle. http://www.seattle.gov/visionzero

- 8.Vision Zero Boston. https://www.boston.gov/transportation/vision-zero

- 9.City of New York. 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/visionzero/downloads/pdf/vision-zero-year-6-report.pdf

- 10.Vision Zero. Speed limit reduction and traffic injury prevention in New York City. East Econ J. 2020;46(2):282–300. doi: 10.1057/s41302-019-00160-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu J, Mohit B, Muennig PA. The cost-effectiveness of bike lanes in New York City. Inj Prev. 2017;23(4):239–243. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiao B, Kim S, Hagen J, Muennig PA. Cost-effectiveness of neighbourhood slow zones in New York City. Inj Prev. 2019;25(2):98–103. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Jiao B, Zafari Z, Muennig P. Optimising the cost-effectiveness of speed limit enforcement cameras. Inj Prev. 2019;25(4):273–277. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282(6279):1847–1851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richard CM, Magee K, Bacon-Abdelmoteleb P, Brown JL. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2018. [Google Scholar]