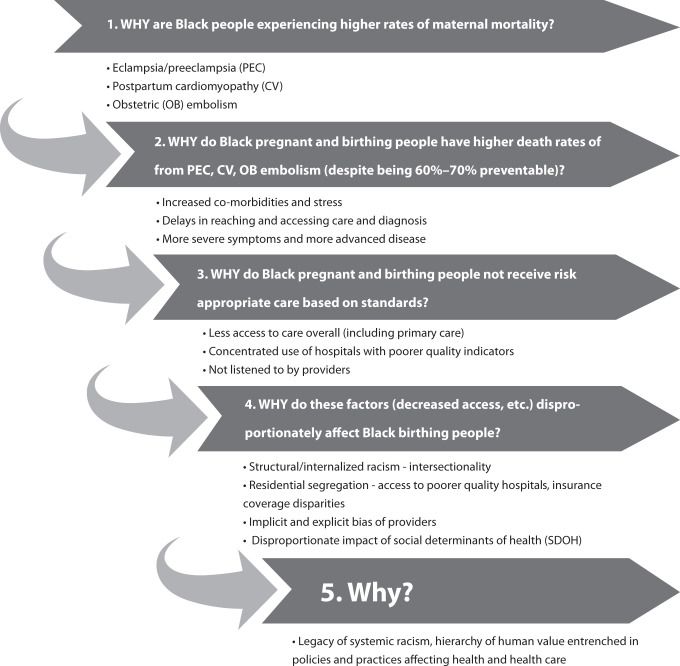

In this issue of AJPH, MacDorman et al. (p. 1673) add a new analysis of cause of death data, underscoring that inequities in maternal mortality persist. Findings highlight the importance of identifying causes and accelerating actions to address racial inequities in maternal mortality. This is essential for changing the narrative about why Black people are more likely to experience pregnancy-related deaths than are non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and others. We must use methods of inquiry that continue to ask why at each level (https://bit.ly/2TwnO4l; Figure 1). Asking why leads us away from “mother blame” narratives or a singular focus on health behaviors of birthing people and toward naming structural racism as a root cause and assessing unequal treatment in the health care system.1

FIGURE 1.

The 5 Whys: Understanding Root Causes of Maternal Mortality

The authors report that the maternal mortality rate for Black people is 3.5 times that of White people. Their analysis on cause of death addresses why we see these unacceptable inequities. Their findings suggest that the excess maternal deaths are attributable to higher rates of eclampsia and preeclampsia, postpartum cardiomyopathy, and obstetric embolism. Thus, increased vigilance for cardiovascular problems during and after pregnancy may reduce disparities in maternal mortality.

To understand why Black people have higher death rates from eclampsia and preeclampsia, postpartum cardiomyopathy, and obstetric embolism—despite mortality from these conditions being 60% to 70% preventable—we must go beyond addressing individual risk factors. Numerous scholars have described the unique stress and discrimination Black women face across their lifetimes and the toll this takes on health (https://bit.ly/3iKonjy). Additionally, people of color are less likely to receive preventive health services irrespective of income, neighborhood, comorbid illness, or insurance type, and they often receive lower quality care. Therefore, Black and Indigenous people2 frequently contend with delays in care or diagnosis for cardiovascular and other diseases that increase the risk of maternal mortality.

But why are Black people so much less likely than their White peers to receive risk appropriate care based on standards? Evidence indicates the need for access to care before, during, and after pregnancy. Access to care is necessary but insufficient to achieving equitable outcomes, and Black pregnant and birthing people are disproportionately served by poorer quality institutions. One study found that predominantly Black-serving hospitals were more likely than predominantly White-serving hospitals to perform worse on 12 of 15 quality indicators for labor and delivery.3 Additionally, Black birthing people are far more likely than their White peers to report being treated unfairly or unjustly by providers.4–6 Finally, even the best quality preventive care cannot eliminate disparities in maternal mortality if Black people do not have equitable access to key social determinants of health. Study after study finds that people of color in the United States are disproportionately unable to access resources critical to health and well-being.

The disparities in Black maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity are rooted in structural racism and slavery’s legacies.7 These legacies and resulting policies and practices shape access to social determinants of health, access to high-quality health care, and the implicit and explicit biases that affect how Black people are treated in health care settings. Racism is expressed through bias and unequal treatment in health care, lack of access to high-quality and equitable care, and lack of continuous health coverage or access.8

How do we begin to address these problems? A focus on systems instead of individuals is key. And policy action must focus on drivers that have an outsize impact on health and well-being, including economic stability, neighborhood and physical environment, food security, and community safety. Health care coverage and access to systems of high-quality prenatal care are critical; however, we cannot expect health care to “fix” or make up for nonmedical contributors during nine months of prenatal care. Policies must be informed by a deep understanding of historical structural inequities and incorporate the perspectives and solutions of Black pregnant and birthing people and their communities.

We need policies that advance health coverage beyond pregnancy and make investments in equity-oriented primary health care.9 Because more than half of pregnancy-related mortality is preventable, targeted improvements to health coverage and care—including services that address physical, reproductive, and behavioral health needs—can help reduce mortality disparities.

Across the life course, greater attention to preventive and primary health care and health coverage is necessary. Medicaid expansion provides coverage for people who lack the resources to pay for health care out of pocket. Extending Medicaid postpartum coverage one full year is urgent. Under the American Rescue Plan Act, all states can extend Medicaid postpartum coverage for one year. Medicaid pays for nearly half of US births, and in some states upward of two thirds. Yet for many, pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage currently extends only to 60 days postpartum. Too many people who lose their Medicaid coverage shortly after a birth simply fall through the cracks.

Improving quality, safety, and equity of care must be a priority. Delays in recognition, diagnosis, or treatment are key aspects of these inequities. Multiple studies have pointed to the rates of “failure to rescue” (death in the setting of severe morbidity), which disproportionately affect people of color.10 Other studies find differences in access to critical care interventions11 and unmanaged underlying health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, infections, and metabolic disorders.12 Addressing these delays requires understanding why systems allow Black people to experience these delays disproportionately. Better recognition of and accountability for inequities in these delays and missed diagnoses are essential. As the authors note, implementing safety bundles to standardize care and increasing awareness may help address this issue. Additionally, a closer examination is required of how medicine and nursing are taught, and of the guidelines and tools employed in clinical decision-making. Moreover, it also involves implementation of routine patient experience measures that can quantify experiences of racism and discrimination in obstetric settings to build accountability and support quality improvement through an equity lens.13

We know there are real, concrete steps we can take to put the United States on the path to an antiracist, equitable health care system where people of color have the necessary ingredients for a thriving existence that results in healthy pregnancies and births. Let’s change the narrative, tackle the root causes head on, and accelerate the pace of change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Jodie Katon and Kay Johnson for useful discussions and review, and Yaphet Getachew for his research assistance.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

See also MacDorman et al., p. 1673.

References

- 1.Scott KA, Britton L, McLemore MR. The ethics of perinatal care for Black women: dismantling the structural racism in “mother blame” narratives. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2019;33(2):108–115. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Tofte AN, Admon LK. Severe maternal morbidity and mortality among Indigenous women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(2):294–300. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black–White differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):122.e1–122.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Patient-reported communication quality and perceived discrimination in maternity care. Med Care. 2015;53(10):863–871. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidebottom A, Vacquier M, LaRusso E, Erickson D, Hardeman R. Perinatal depression screening practices in a large health system: identifying current state and assessing opportunities to provide more equitable care. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(1):133–144. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01035-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16:77. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens DC, Fett SM. Black maternal and infant health: historical legacies of slavery. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1342–1345. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(2):230–235. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, et al. Closing the health equity gap: evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Huang Y, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Hospital delivery volume, severe obstetrical morbidity, and failure to rescue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):795e1–795.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kern-Goldberger AR, Friedman A, Moroz L, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Racial disparities in maternal critical care: are there racial differences in level of care? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01000-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh GK, Lee H. Trends and racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities in maternal mortality from indirect obstetric causes in the United States, 1999–2017. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):43–54. doi: 10.21106/ijma.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers BD, Arega HA, Arabia SE, et al. Black women’s perspectives on structural racism across the reproductive lifespan: a conceptual framework for measurement development. Matern Child Health J. 2021;25(3):402–413. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]