Abstract

Several hybridomas producing antibodies detected by indirect immunofluorescence antibody test (IFAT) were established by fusion of mouse myeloma SP2/O with spleen cells from BALB/c mice immunized against whole spores (protocol 1) or chitinase-treated spores (protocol 2) of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and were cloned twice by limiting dilutions. Two monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), 3B82H2 from protocol 1, isotyped as immunoglobulin M (IgM), and 6E52D9 from protocol 2, isotyped as IgG, were expanded in both ascites and culture. IFAT with the MAbs showed that both MAbs reacted exclusively with the walls of the spores of E. bieneusi, strongly staining the surface of mature spores, and produced titers of greater than 4,096. Immunogold electron microscopy confirmed the specific reactivities of both antibodies. No cross-reaction, either with the spores of the other intestinal microsporidium species Encephalitozoon intestinalis or with yeast cells, bacteria, or any other intestinal parasites, was observed. The MAbs were used to identify E. bieneusi spores in fecal specimens from patients suspected of having intestinal microsporidiosis. The IFAT was validated against standard staining methods (Chromotrope 2R and Uvitex 2B) and PCR. We report here the first description and characterization of two MAbs specific for the spore wall of E. bieneusi. These MAbs have great potential for the demonstration and species determination of E. bieneusi, and their application in immunofluorescence identification of E. bieneusi in stool samples could offer a new diagnostic tool for clinical laboratories.

Microsporidia are obligate intracellular protistan parasites that infect a variety of cells from a wide range of invertebrate and vertebrate hosts. Also identified in humans, more especially in immunocompromised patients, microsporidia appear to be major opportunistic pathogens. These parasites were shown to be the prevalent cause of intestinal infections reported in patients with AIDS and diarrhea (17, 21) in industrialized countries. Significantly, the introduction of antiretroviral combination regimens including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors has resulted in a decrease in the number of cases of AIDS-related microsporidiosis (10, 12).

The first documented case of intestinal infection was caused by Enterocytozoon bieneusi (7), the microsporidian species most commonly found in humans. This parasite is usually observed in HIV-infected patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts of less than 50 cells/mm3 who complain of chronic diarrhea, nausea, malabsorption, and severe weight loss (4, 24). Encephalitozoon intestinalis (14) also causes intestinal infections frequently associated with nephritis, sinusitis, or bronchitis (17, 21). These parasites are also pathogenic in subjects with immunodeficiency due to causes other than AIDS. Cases of intestinal microsporidiosis have been detected in organ transplant recipients (25, 28). The two species E. bieneusi and E. intestinalis also appear to be responsible for cases of diarrhea in immunocompetent subjects (11). Most of them are presented by travellers returning from tropical areas (26, 27, 29, 34). Less expected is the increasing number of HIV-seronegative and asymptomatic individuals found to be infected with microsporidia (8, 15, 32).

Over the past 10 years, different diagnosis methods, based on the detection of the parasites' spores in stools and other biological samples, have been proposed (3, 16, 31, 39). Although PCR appears to be the most sensitive method (6, 9, 11, 23), immunological tools remain helpful for diagnosis and for epidemiological survey or experimental investigation. Specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against E. intestinalis isolates easily obtained through in vitro systems have been produced (5). To date, such systems are still lacking for E. bieneusi. However, spores of this species extracted from fecal samples enabled the production of the MAbs described in the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources of parasites. (i) E. bieneusi.

In the absence of an in vitro cultivation model and due to the invasive procedures needed for collecting epithelium or fluid samples from the gastrointestinal tract, human stools were the source of E. bieneusi spores. Fecal specimens were obtained from HIV-infected patients. Microsporidian spores were detected by fluorochrome Uvitex 2B stain (31) and Weber's chromotrope-based modified trichrome stain (16). Fecal samples containing numerous small oval spores were homogenized and suspended in a solution of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma Laboratories, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). The samples were processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and tested by PCR to confirm the identification of the species and to exclude a concomitant E. intestinalis infection.

(ii) TEM.

The fecal samples were fixed at room temperature in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 60 min, rinsed in buffer, and then postfixed in ferriosmium [1% (wt/vol) OsO4 and K3Fe(Cn)6 in cacodylate buffer] for 60 min. After ethanolic dehydration, the samples were embedded in Spurr resin. Thin sections, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, were examined with a JEOL JEM 100 CX transmission electron microscope.

(iii) PCR amplification.

The PCR assay was performed as described previously by Ombrouck et al. (23). The primers V1 (5′-CACCAGGTTGATTCTGCCTGAC-3′) and EB450 (5′-ACTCAGGTGTTATACTCACGTC-3′) described by Zhu et al. (38) were used to amplify E. bieneusi DNA. The primers V1 and SI500 (5′-CTCGCTCCTTTACACTCGAA-3′) described by Weiss et al. (37) were used to amplify E. intestinalis DNA.

(iv) E. intestinalis.

Spores were obtained from cultures in rabbit kidney cells (RK13), as described by van Gool et al. (30). Parasite spores were harvested weekly, counted in a hemocytometer, resuspended in PBS, and stored at 4°C until used.

Antigen preparation procedures. (i) Spore concentration.

The stool suspension was filtered through a graded series of six nylon sieves (pore diameters were 100, 50, 30, 20, 10, and 5 μm, respectively). The filtration was facilitated by the addition of 1,000 to 2,000 ml of PBS. The final filtrate was centrifuged at 500 × g for 6 min to eliminate large particles, and the sieved spores in the supernatant were pelleted by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in PBS (1/3 [vol/vol]).

(ii) Spore purification.

Density gradient centrifugation was performed with various concentrations of Percoll (19). The discontinuous gradient consisted of 10 ml of stock isotonic Percoll solution (prepared by mixing 10 ml of 10-fold-concentrated PBS and 90 ml of Percoll [Sigma Laboratories] to yield a pH of 7.4 and an osmolarity of 335 mosM), 10 ml of 67.5% stock Percoll diluted with PBS, 10 ml of 45% stock Percoll diluted with PBS, and 10 ml of 22.5% stock Percoll diluted with PBS. Five milliliters of the spore suspension was layered over the gradient into a 50-ml Falcon centrifuge tube. After centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 30 min at 15°C, four distinct bands were formed. The clearly defined ring at the 90 to 67.5% Percoll interface, previously determined to contain whole spores by light microscopy and TEM (results not shown), was collected, washed three times in PBS, pelleted at 2,500 × g for 20 min, and resuspended in PBS (1/3 [vol/vol]).

(iii) Sterilization.

To monitor for bacterial and fungal contaminants, the isolate of spores was mixed with an antibiotic solution of ceftriaxone (20 μg/ml), vancomycin (10 μg/ml), amikacin (10 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml) and placed at 4°C. Antibiotics were added daily at the same concentration until sterilization of the preparation as determined by aerobic and anaerobic cultivation was achieved. After 3 to 5 days of this regimen, the sterile concentrate was centrifuged at 2,500 × g for 20 min and washed twice in sterile PBS.

The pellet was then divided into two aliquots of 1 ml each in sterile PBS, in one of which spores were incubated for 60 min at room temperature with 50 μl of a concentrated (5 IU/ml) chitinase from Serratia marcescens (Sigma Laboratories), treated by two freeze-thaw cycles, centrifuged at 2,500 × g for 20 min, and examined after fluorochrome Uvitex 2B stain.

Aliquots were resuspended and diluted in sterile 0.15 M NaCl (1/3 [vol/vol]). Spore counts were performed by using 2-μl droplets applied to 5-mm-wide wells on multiwell slides, stained according to the Uvitex 2B method.

Production of MAbs.

Adult (6-week-old) female BALB/c mice, for hybridoma development and ascites production, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Saint-Aubin-les-Elbeuf, France). Two protocols of immunization, using two groups of six mice each, were carried out. In protocol 1, animals received whole spores of E. bieneusi; in protocol 2, they received chitinase-treated spores. All the animals were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p.) four times at 3-week intervals with 5.6 × 107 spores per 100 μl emulsified at a 1:1 ratio in Freund's complete adjuvant (Sigma Laboratories) for the first inoculation and in Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Sigma Laboratories) for the other three inoculations. Two control mice were not injected.

Seven days after each immunization, sera were screened by indirect immunofluorescence as described below to determine which mice had the highest parasite-specific antibody responses. Mouse serum adsorption experiments were performed with an antigen preparation of enteropathogenic bacteria and yeasts isolated from human stool samples and grown on aerobic culture. The preparation was added to serum samples prediluted in PBS, which subsequently were shaken at room temperature for 120 min and spun down (10,000 × g, 5 min). Measurements were done by using the supernatants. Sera were stored at −80°C and used as positive controls during all immunoassays.

Two of the immunized mice, one in each group, were selected to receive a further intravenous dose of 2 × 107 spores in 100 μl of sterile 0.15 M NaCl, and their spleens were used for the fusion protocol 3 days later (one fusion protocol per immunization protocol). Cells of the murine myeloma line SP2/O were fused with spleen cells from the donor mouse at a 1:5 ratio in 50% polyethylene glycol (Sigma Laboratories) (13). Stable hybrids were selected by growth in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum, hypoxanthine, aminopterin, and thymidine as previously described (33). Supernatant culture medium was screened by an indirect immunofluorescence antibody test (IFAT). Hybridoma cultures whose supernatants showed antibody activity against E. bieneusi were expanded onto 24-well plates and cloned twice by limiting dilutions (13). Pristane-primed female BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 106 cells from each hybridoma line, and ascitic fluid was collected 10 to 15 days later, centrifuged (400 × g for 15 min) to remove cells, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until used (13). Culture supernatants of the different hybridoma lines were also collected. MAbs were purified from ascites or supernatants with Dynabeads M-450 rat anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM) and M-450 rat anti-mouse IgG2a (Dynal, Compiègne, France), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

IFAT.

The IFAT was performed with (i) washed whole spores of E. bieneusi, which were used for the immunization in protocol 1, suspended in PBS to obtain 108 spores per ml and (ii) E. intestinalis spores from tissue culture supernatants resuspended in PBS at 109 spores per ml, as antigens. Antigen slides were prepared by depositing 2-μl volumes of the spore suspension onto each well of 18-well slides, which were then air dried and fixed in ice-cold acetone for 10 min.

Undiluted supernatants of hybridoma cultures or the ascitic fluid, serially diluted twofold in 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS starting from a 1:2 dilution, were transferred to the 18-well slides (20 μl of each dilution per well), and the slides were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in a moist chamber. The slides were then washed three times in PBS at 10-min intervals, and each well was then covered with 20 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG-IgM-IgA (Sigma Laboratories) at a dilution of 1:200 containing Evans blue as the counterstain. The slides were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and washed three times as described above, coverslips were added with buffered glycerol mounting fluid, and the slides were examined with a Leitz Laborlux fluorescence microscope equipped with epifluorescence illumination. PBS and conjugate controls were included with each slide.

Characterization of anti-E. bieneusi MAbs. (i) Isotyping.

The MAb isotypes were determined with a dipstick isotyping kit (Sigma Laboratories) according to the instructions enclosed.

(ii) Ultrastructural immunolocalization.

Stool samples from patients with an E. bieneusi infection were purified by gentle filtration and Percoll discontinuous gradient as described earlier. Then they were fixed at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde–0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.15 M Na cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 45 min and rinsed three times at 10-min intervals in 0.1 M ammonium chloride in cacodylate buffer and one time for 10 min in cacodylate buffer alone. After ethanolic dehydration, the material was embedded in LR WHITE resin. The sections were collected on gold or nickel grids. They were incubated at room temperature in 1% BSA in PBS for 45 min to block unbound sites and then for 120 min with ascitic fluid containing MAbs (1:512). After a series of six washings (5 min each), in 0.25% BSA in PBS, sections were incubated for 60 to 120 min with goat anti-mouse affinity-purified IgM or goat anti-mouse affinity-purified IgG labelled with 10-μm gold particles (Sigma Laboratories) used as second antibody. Controls consisted of sections incubated with the second antibody alone. After being washed in sterilized water, samples were examined with a JEOL JEM 100 CX transmission electron microscope.

(iii) SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed with E. intestinalis spores used as antigens. Parasite proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to the method of Laemmli (18), with a 5% stacking gel and a 12% resolving gel. Intact spores in 1 ml of sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol were boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at 10,000 × g to remove particulate materials. Each preparative slab gel (16 by 20 cm) was loaded with 2 × 109 parasites. After electrophoresis, the separated polypeptides were electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (pore diameter, 0.22 μm; Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) which was then incubated with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk (Régilait) in PBS for 60 min to block unbound sites, washed in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween) for 20 min and cut into 3-mm-wide longitudinal strips. The strips were incubated for 60 min with either undiluted supernatants or ascitic fluid containing MAbs (1:512), murine immune sera, preimmune murine sera, or a specific E. intestinalis IgG3 6C12C11 MAb previously developed in our laboratory (unpublished data) as a positive control. After being washed in PBS-Tween, strips were incubated for 60 min with affinity-purified peroxidase-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG-IgM antiserum (Sigma Laboratories) diluted 1:2,000 and developed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma Laboratories) after being washed with three changes of PBS-Tween. After color development for 30 min, the strips were rinsed in distilled water, dried, and stored in the dark.

(iv) Cross-reactivity studies.

The reactivity of the MAbs with bacteria, parasites, and fungi was assessed by IFAT.

Utilization of MAbs in diagnosis and comparison with other methods.

Fifteen diarrheal fecal samples containing microsporidial spores and 25 negative stool samples were collected and preserved in PBS with 10% Formol (1/3 [vol/vol]). Intestinal microsporidiosis had been previously diagnosed in the 15 patients by classical staining methods (16, 31). The fecal samples were filtered through a 50-μm-pore-diameter filter, and after ether sedimentation by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 15 min, the pellet was suspended in PBS (1/3 [vol/vol]) and applied to slides. All the stool samples were coded and blind-tested by IFAT. The specificities of the MAbs were evaluated by comparison with PCR and TEM (if available) performed as described previously.

RESULTS

MAb production.

Prior to immunization, mouse sera were screened for antibodies against intestinal microsporidium spores by IFAT and Western blot analysis, with E. bieneusi and E. intestinalis spores as antigens. Preimmunization sera and healthy-mouse-control sera did not react with any of the parasite spores. Because they were immunized with impure antigens, BALB/c mice were screened for serum parasite-specific antibody response 7 days after each injection before a final boost and fusion. All mice began to produce antibodies after the second i.p. injection. The highest antibody response was raised after the fourth injection. Sera from mice 2-1 (protocol 1) and 3-2 (protocol 2) produced the better fluorescence (limiting dilution, 1:100). These two mice were thus selected for the fusion protocol.

For each immunization protocol, a single fusion was performed with spleen cells of the donor mouse. A total of 960 wells were seeded with fused SP2/O myeloma cells, and their supernatants began to be screened by whole spore E. bieneusi IFAT 11 days after fusion. After the third screening, six antibody-secreting hybridomas still reacted against spores of E. bieneusi. After two cloning procedures by limiting dilutions, two stable clones, clone 3B82H2 from protocol 1 and clone 6E52D9 from protocol 2, were obtained. Isotype determination revealed that clone 3B82H2 secreted IgM and clone 6E52D9 secreted IgG2a. The two MAbs were expanded in both ascites and culture and subjected to thorough screening.

IFAT.

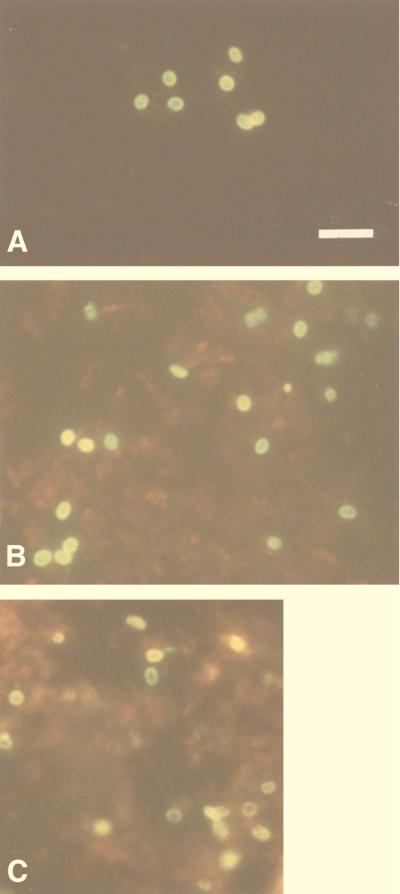

The two MAbs showed strong indirect immunofluorescence after incubation with whole purified E. bieneusi spores, almost to the same extent, and yielded titers of greater than 4,096. All reacted exclusively with the walls of the spores, which fluoresced brightly and were thus easily recognized with a ×1,000 magnification (Fig. 1A and B). 3B82H2 and 6E52D9 showed mutual competition in their binding to E. bieneusi when the two MAbs were combined in one IFAT. No fluorescence was observed on E. intestinalis spore walls or filaments or when FITC-conjugated second antibody was employed alone.

FIG. 1.

Purified whole spores of E. bieneusi stained by indirect immunofluorescence with MAbs 6E52D9 (A) and 3B82H2 (B) in ascitic fluid. MAbs recognize antigens localized in the spores walls. (C) Formalin-fixed smear of a fecal sample, from one of the 14 patients with microsporidia, reacted with a 1:512 dilution of MAb 6E52D9. Note the bright fluorescence of spore walls. Bar = 5 μm.

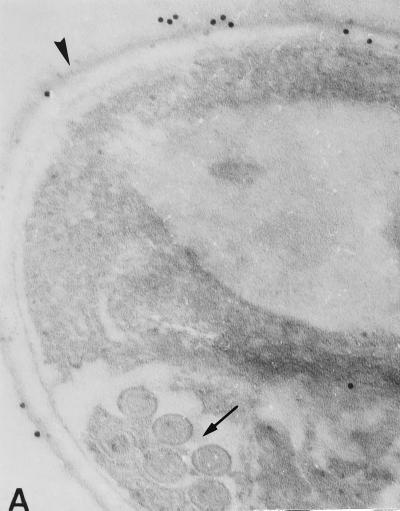

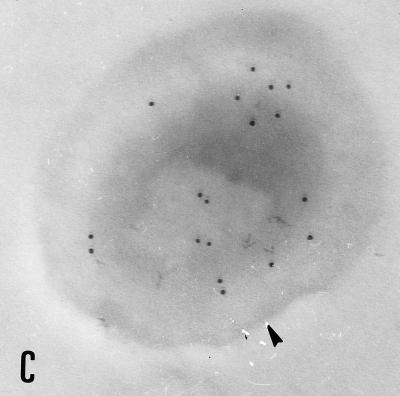

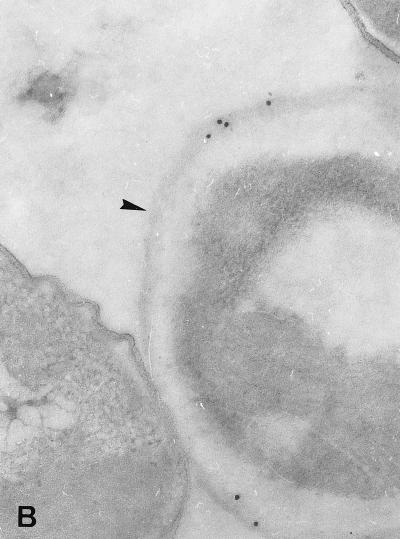

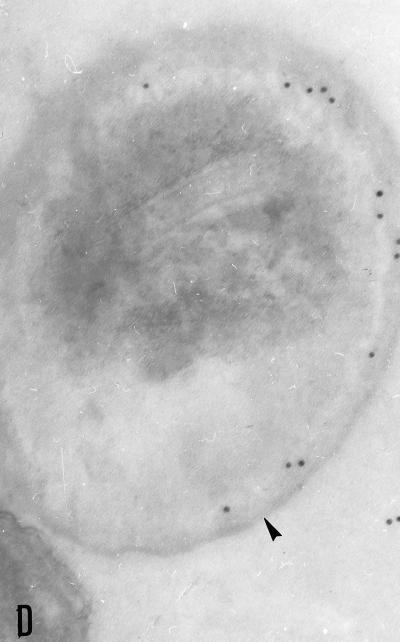

Characterization of the MAbs. (i) Ultrastructural immunolocalization.

The binding of each MAb to E. bieneusi spores was studied by TEM which revealed a labelling of the spore wall, more especially when sections of mature spores were incubated with 3B82H2 or 6E52D9 MAb. Interestingly, different parts of the spore wall reacted with these MAbs. Gold particles were exclusively distributed over the exospore in specimens treated with the IgG MAb 6E52D9 (Fig. 2A and B), whereas a labelling of the endospore was obtained with the IgM MAb 3B82H2 (Fig. 2C and D). No labelling was observed when sections were incubated with the second antibody alone. No reactivity was displayed by E. intestinalis spores collected in culture supernatants or in stool samples. The immunogold labelling of the spore wall was consistent with the IFAT results.

FIG. 2.

Immunogold electron micrographs of E. bieneusi mature spores after incubation with MAb 6E52D9 and MAb 3B82H2. (A) Labelling of the outer layer of the spore wall (exospore [arrowhead]) with MAb 6E52D9. The arrow indicates the double row arrangement of E. bieneusi polar tube sections. Magnification, ×120,000. (B) The MAb selectively labels the exospore (arrowhead). No gold particles are visible at the surface or inside the bacteria (left). Magnification, ×100,000. (C) The tangential section of the spore treated with MAb 3B82H2 shows the distribution of gold particles in the internal layer of the wall (endospore [arrowhead]). Magnification, ×100,000. (D) Labelling of the endospore (arrowhead) with the same MAb. Magnification, ×100,000.

(ii) Western blot analysis.

Neither of the two MAbs reacted with E. intestinalis antigens by Western blot analysis, compared to an IgG3 6C12C11 MAb directed against E. intestinalis whole spores.

(iii) Cross-reactivity studies.

By IFAT, MAbs in ascitic fluid were assessed for cross-reactivity to enteropathogenic bacteria (Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella dysenteriae, Salmonella typhi, Yersinia enterocolitica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterococcus faecalis), other intestinal parasites (Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba coli, Cryptosporidium parvum, Sarcocystis hominis, Isospora belli, Blastocystis hominis), and yeasts from stool samples. There was no cross-reactivity even at the 1:128 dilution to any of the organisms evaluated.

Utilization of MAbs in diagnosis and comparison with other methods.

By Uvitex 2B and Weber's modified trichrome staining methods, spores with the morphological features characteristic of microsporidia (16, 31) were detected in fecal specimens from 15 patients. Among these samples, 14 contained small oval spores suggestive of E. bieneusi, whereas 1 stool contained larger spores suggestive of E. intestinalis.

By IFAT, the two MAbs reacted exclusively with the small oval spores present in the 14 samples (Table 1). These spores fluoresced brightly, 4+ in a scale of 0 to 4, with a prominent labelling of the spore walls when smears were treated with 3B82H2 or 6E52D9 MAb at 1:512 and 1:1,024 dilutions (Fig. 1C). Neither of the two MAbs generated background in formalin-fixed stool specimens. No fluorescence was observed either in the stool containing larger spores suggestive of E. intestinalis or in stools from patients without intestinal microsporidiosis.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of four diagnostic methods for the 15 patients with microsporidia detected by stained smears of stool samplesa

| Case no. | Sexc | Age (yr) | HIV status | No. of CD4/mm3 | Stool sample results by:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light microscopyb

|

PCRd

|

TEM | IFAT

|

||||||||

| Small | Large | E. bieneusi | E. intestinalis | 3B82H2 | 6E52D9 | ||||||

| 1 | M | 30 | + | 44 | N | + | − | ND | + | + | |

| 2 | M | 16 | − | 737 | VN | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 3 | M | 52 | + | 0 | R | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 4 | M | 42 | + | 119 | F | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 5 | F | 26 | + | 13 | N | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 6 | M | 38 | + | 35 | N | + | − | ND | + | + | |

| 7 | M | 39 | + | 23 | R | + | − | ND | + | + | |

| 8 | M | 29 | + | 10 | N | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 9 | F | 35 | + | 3 | VN | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 10 | M | 39 | + | 41 | R | − | + | E. intestinalis | − | − | |

| 11 | M | 49 | + | 20 | N | + | − | ND | + | + | |

| 12 | M | 50 | − | ND | N | + | − | ND | + | + | |

| 13 | M | 52 | + | 6 | N | + | − | E. bieneusi | + | + | |

| 14 | M | 45 | + | 40 | F | + | − | ND | + | + | |

| 15 | M | 34 | + | 15 | VN | + | − | ND | + | + | |

+, positive; −, negative; ND, not done.

Uvitex 2B stain and Weber's modified trichrome stain were performed for all patients. Spores were classified as either small (diameter, 1 to 1.5 μm) or large (diameter, 1.2 to 2.2 μm). Classification of spore quantity per microscopic field (magnification, ×1,000; oil immersion): VN, very numerous; N, numerous; F, few; R, rare.

M, male; F, female.

Specific PCR assay for direct detection of intestinal microsporidia.

The IFAT was compared for reliability with the PCR and TEM (if available). The results were consistent with those of IFAT (Table 1). The microsporidian species of each positive sample was confirmed and E. bieneusi but not E. intestinalis spores were recognized by MAbs 6E52D9 and 3B82H2. By PCR, no signals were observed for the 25 fecal specimens negative for microsporidia.

DISCUSSION

We report here the production, characterization, and reactivity of the first MAbs directed against E. bieneusi, the most common microsporidium infecting AIDS patients. Since there is no in vitro culture system presently available, it has been impossible to produce enough antigen to screen for specific antibodies. We circumvented this problem by developing a procedure for the isolation, purification, and sterilization of parasite spores from human stools. Apparently, the best preservation of the spore antigens is obtained when using gentle filtration, centrifugation in isotonic conditions, and gradual addition of low concentrations of antibiotics to the final fecal suspension.

The most difficult part of the study was identification of an MAb with the desired specificity because immunization was done with impure antigenic material and assays to detect the desired MAb were not available. However, the IFAT performed with E. bieneusi-purified whole spores as antigens appeared to be specific enough to select the MAbs that bound to spore walls, and the results of the immunofluorescence assays could be confirmed at the ultrastructural level by TEM.

Of the two MAbs, one belongs to the IgM class (protocol 1) and the other belongs to the IgG class (protocol 2). The specific reactivity of the selected antibodies depends on the nature of the immunogen. Significantly, the MAb 3B82H2 reactive with the endospore known to contain chitin was raised against the antigenic fraction which was not treated with chitinase.

Extensive cross-reactivities among different microsporidian species have been observed with polyclonal sera from rabbits immunized with a single microsporidian species (22). More recently, polyclonal antisera raised against Encephalitozoon cuniculi in rabbits or in mice were used in the IFAT to detect E. bieneusi organisms in deparaffinized tissue sections (36) and in stool (3, 39). Using the MAbs described in this study in either IFAT, TEM or Western blot analysis, we did not observe any cross-reactions with the other human intestinal microsporidium, E. intestinalis, or with other intestinal parasites, yeast cells, or bacteria.

The reference techniques used for the comparative detection of microsporidia directly from fecal specimens were PCR, TEM, and Uvitex 2B and Weber's modified trichrome stainings. Immunofluorescence assay with MAbs appeared to be highly specific. E. bieneusi spores were identified in the 14 stool specimens with complete concordance with the results of PCR and TEM (if available). The sensitivities of the MAbs in detecting subclinical infections seemed attractive. Indeed, the diagnosis could be performed even when few spores were excreted in stool samples. It is noteworthy that no background was observed in the fecal specimens which were examined by the immunofluorescence protocol described herein. Moreover, the application of these MAbs as tools for detecting E. bieneusi in feces does not require either pretreatment of the samples or absorbing the FITC-conjugated antibodies with formalin-fixed stool sediment, as described by others (3, 5).

Diagnosis of microsporidiosis to the species level is essential for the treatment of patients. To date, although different therapeutic agents are effective against most microsporidian species, none can eradicate E. bieneusi except fumagillin, which is still under investigation (20). Presently, the identification of human microsporidia to the species level requires time-consuming methods such as electron microscopy and molecular techniques (6, 7, 9, 11, 23, 35). The two MAbs newly described in this study are the first to be raised against E. bieneusi. Their application in the immunofluorescence identification of this organism could offer a new diagnostic tool for clinical laboratories. The bright fluorescence of the spore wall facilitates the diagnosis even for the untrained eye. In addition these MAbs could offer new approaches for the study of E. bieneusi. Used as ligands, they could enable the isolation and purification of E. bieneusi spores with methods such as affinity chromatography or immunomagnetic separation. Ongoing studies will determine the usefulness of these techniques in our follow-up assays to develop in vivo (1, 2) or in vitro models of E. bieneusi as well as in Western blot analysis or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jean Jacques Hauw for providing TEM facilities and Jacques Breton for revising the manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from SIDACTION.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accoceberry I, Carrière J, Thellier M, Biligui S, Danis M, Datry A. Rat model for the human intestinal microsporidian Enterocytozoon bieneusi. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44:83S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accoceberry I, Greiner P, Thellier M, Achbarou A, Biligui S, Danis M, Datry A. Rabbit model for human intestinal microsporidia. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44:82S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldras A M, Orenstein J M, Kotler D P, Shadduck J A, Didier E S. Detection of microsporidia by indirect immunofluorescence antibody test using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:608–612. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.608-612.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asmuth D M, DeGirolami P C, Federman M, Ezratty C R, Pleskow D K, Desai G, Wanke C A. Clinical features of microsporidiosis in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:819–825. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckers P J A, Derks G J M M, van Gool T, Rietveld F J R, Sauerwein R W. Encephalitozoon intestinalis-specific monoclonal antibodies for laboratory diagnosis of microsporidiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:282–285. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.282-285.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Silva A J, Schwartz D A, Visvesvara G S, de Moura H, Slemenda S B, Pieniazek N J. Sensitive PCR diagnosis of infections by Enterocytozoon bieneusi (microsporidia) using primers based on the region coding for small-subunit rRNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:986–987. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.986-987.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desportes I, Le Charpentier Y, Galian A, Bernard F, Cochand-Priollet B, Lavergne A, Ravisse P, Modigliani R. Occurrence of a new microsporidian, Enterocytozoon bieneusi n.g., n.sp., in the enterocytes of a human patient with AIDS. J Protozool. 1985;32:250–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enriquez F J, Taren D. Prevalence of intestinal microsporidiosis in Mexico. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1227–1229. doi: 10.1086/520278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedorko D P, Nelson N A, Cartwright C P. Identification of microsporidia in stool specimens by using PCR and restriction endonucleases. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1739–1741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1739-1741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foudraine N A, jan Weverling G, van Gool T, Roos M T L, de Wolf F, Koopmans P P, van den Broek P J, Meenhorst P L, van Leeuwen R, Lange J M A, Reiss P. Improvement of chronic diarrhoea in patients with advanced HIV-1 infection during potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:35–41. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gainzerain J C, Canut A, Lozano M, Labora A, Carreras F, Fenoy S, Navajas R, Pieniazek N J, da Silva J, del Aguila C. Detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in two human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with chronic diarrhea by polymerase chain reaction in duodenal biopsy specimens and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:394–398. doi: 10.1086/514660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goguel J, Katlama C, Sarfati C, Maslo C, Leport C, Molina J M. Remission of AIDS-associated intestinal microsporidiosis with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1997;11:1603–1610. . (Letter.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 139–245. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartskeerl R A, van Gool T, Schuitema A R J, Didier E S, Terpstra W J. Genetic and immunological characterization of the microsporidian Septata intestinalis Cali, Kotler and Orenstein, 1993: reclassification to Encephalitozoon intestinalis. Parasitology. 1995;110:277–285. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hautvast J L, Tolboom J J, Derks T J, Beckers P, Sauerwein R W. Asymptomatic intestinal microsporidiosis in a human immunodeficiency virus—seronegative immunocompetent Zambian child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:415–416. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199704000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokoskin E, Gyorkos T W, Camus A, Cedilotte L, Purtill T, Ward B. Modified technique for efficient detection of microsporidia. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1074–1075. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1074-1075.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotler D P. Gastrointestinal manifestations of immunodeficiency infection. Adv Intern Med. 1995;40:197–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medina de la Garza C E, Garcia-Lopez H L, Salinas-Carmona M C, Gonzalez-Spencer D J. Use of discontinuous Percoll gradients to isolate Cyclospora oocysts. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:319–321. doi: 10.1080/00034989761166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molina J M, Goguel J, Sarfati C, Chastang C, Desportes-Livage I, Michiels J F, Maslo C, Katlama C, Cotte L, Leport C, Raffi F, Derouin F, Modaï J. Potential efficacy of fumagillin in intestinal microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi infections in patients with HIV infection; results of a drug screening study. AIDS. 1997;11:1603–1610. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199713000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molina J M, Sarfati C, Beauvais B, Lémann M, Lesourd A, Ferchal F, Casin I, Lagrange P, Modigliani R, Derouin F, Modaï J. Intestinal microsporidiosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with chronic and unexplained diarrhea: prevalence and clinical and biologic features. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:217–221. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niederkorn J Y, Shadduck A, Weidner E. Antigenic cross-reactivity among different microsporidian spores as determined by immunofluorescence. J Parasitol. 1980;66:675–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ombrouck C, Ciceron L, Biligui S, Brown S, Marechal P, van Gool T, Datry A, Danis M, Desportes-Livage I. Specific PCR assay for direct detection of intestinal microsporidia Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis in fecal specimens from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:652–655. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.652-655.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orenstein J M. Microsporidiosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Parasitol. 1991;77:843–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabodonirina M, Bertocchi M, Desportes-Livage I, Cotte L, Levrey H, Piens M A, Monneret G, Celard M, Mornex J F, Mojon M. Enterocytozoon bieneusi as a cause of chronic diarrhea in a heart-lung-transplant recipient who was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:114–117. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raynaud L, Delbac F, Broussolle V, Rabodonirina M, Girault V, Wallon M, Cozon G, Vivares C P, Peyron F. Identification of Encephalitozoon intestinalis in travelers with chronic diarrhea by specific PCR amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:37–40. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.37-40.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandfort J, Hannemann A, Gelderblom H, Stark K, Owen R L, Ruf B. Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection in an immunocompetent patient who had acute diarrhea and who was not infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:514–516. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sax P E, Rich J D, Pieciak W S, Trnka Y M. Intestinal microsporidiosis in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation. 1995;60:617–618. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199509270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobottka I, Albrecht H, Schottelius J, Schmetz C, Bentfeld M, Laufs R, Schwartz D A. Self limited traveller's diarrhea due to a dual infection with Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Cryptosporidium parvum in an immunocompetent HIV-negative child. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:919–920. doi: 10.1007/BF01691502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Gool T, Canning E U, Gilis H, van der Bergh-Weerman M A, Eeftinck Schattenkerk J K, Dankert J. Septata intestinalis frequently isolated from stools of AIDS patient with a new cultivation method. Parasitology. 1994;109:281–289. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000078318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Gool T, Snijders F, Reiss P, Eeftinck Schattenkerk J K, van der Bergh-Weerman M A, Bartelsman J F W M, Bruins J J M, Canning E U, Dankert J. Diagnosis of intestinal and disseminated microsporidia infections in patients with HIV by a new rapid fluorescence technique. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:694–699. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.8.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Gool T, Vetter J C M, Weinmayr B, van Dam A, Derouin F, Dankert J. High seroprevalence of Encephalitozoon species in immunocompetent subjects. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1020–1024. doi: 10.1086/513963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Visvesvara G S, Peralta M J, Brandt F H, Wilson M, Aloisio C, Franko E. Production of monoclonal antibodies to Naegleria fowleri, agent of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1629–1634. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1629-1634.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wanke C A, Degirolami P, Federman M. Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection and diarrheal disease in patients who were not infected with HIV: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:816–818. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber R, Bryan R T, Schwartz D A, Owen R. Human microsporidial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:426–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss L M, Cali A, Levee E, Laplace D, Tanowitz H, Simon D, Wittner M. Diagnosis of Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection by western blot and the use of cross-reactive antigens for the possible detection of microsporidiosis in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:456–462. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss L M, Zhu X, Cali A, Tanowitz H B, Wittner M. Utility of microsporidian rRNA in diagnosis and phylogeny: a review. Folia Parasitol. 1994;41:81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X, Wittner M, Tanowitz H B, Kotler D, Cali A, Weiss L M. Small subunit rRNA sequence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and its potential diagnostic role with use of the polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1570–1575. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zierdt C H, Gill V J, Zierdt W S. Detection of microsporidian spores in clinical samples by indirect fluorescent-antibody assay using whole-cell antisera to Encephalitozoon cuniculi and Encephalitozoon hellem. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3071–3074. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.3071-3074.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]