Abstract

This study reported the case of a healthy male in his 40s who presented with a 3-month history of frontal headache and post-nasal drip, which did not improve with oral antibiotics. One month prior to the onset of the symptoms, he underwent a nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 (which yielded a negative result) for a history of malaise and cough. The patient claimed that the swab insertion into the nasal cavity was particularly painful on the left side. Sinus computed tomography (CT) scan showed deformity of the left middle nasal turbinate with occlusion of the osteomeatal complex, resulting in ethmoid silent sinus syndrome. This study makes a significant contribution to the literature because nasopharyngeal, midturbinate and anterior nasal swabs have been recommended as initial diagnostic specimen collection methods by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the coronavirus disease 2019. These methods require introducing an instrument into the nasal cavity, potentially leading to adverse effects due to the delicate and complex nasal anatomy. However, complications related to swab testing for respiratory pathogens have not yet been fully discussed in the literature.

Keywords: Silent sinus syndrome, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Nasopharyngeal swab

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, has rapidly spread worldwide since December 2019. Anterior nasal, midturbinate, and nasopharyngeal swabs have been recommended as initial diagnostic specimen collection methods by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [1]. These methods require introducing an instrument into the nasal cavity, potentially leading to adverse effects due to the delicate and complex nasal anatomy. However, complications related to swab testing for respiratory pathogens have not yet been fully discussed in the literature [2]. To our knowledge, this was the first case of iatrogenic ethmoidal silent sinus syndrome after nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2.

Report of a case

A healthy male in his 40s presented with a 3-month history of frontal headache and post-nasal drip, which did not improve with oral antibiotics. One month prior to the onset of the symptoms, he underwent a nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 (which yielded a negative result) for a history of malaise and cough. The patient claimed that the swab insertion into the nasal cavity was particularly painful on the left side. He denied any history of facial trauma, nasal surgery, or chronic sinusitis, and his medical history was unremarkable.

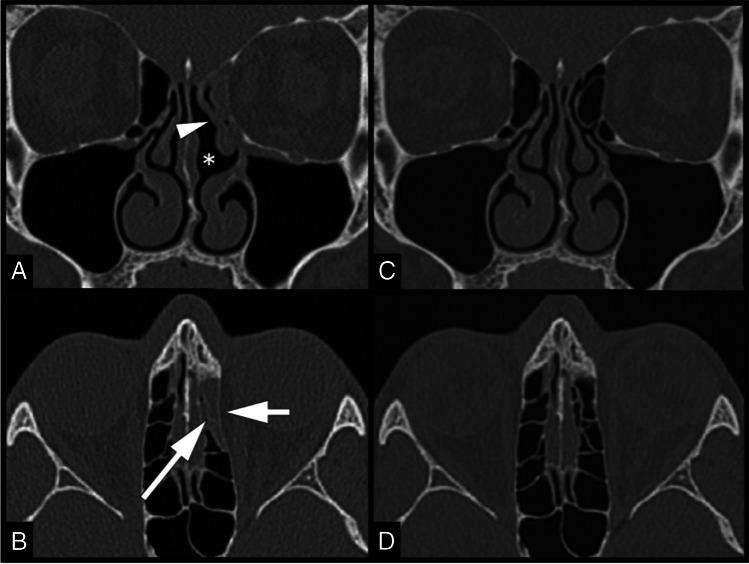

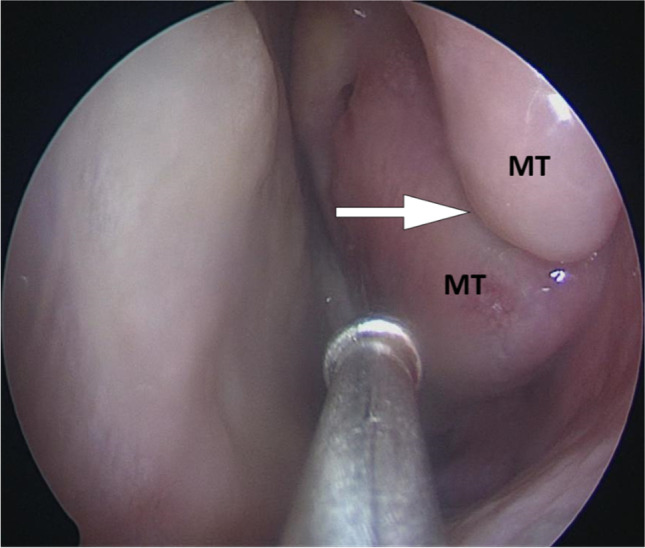

Sinus computed tomography (CT) scan showed a lateral deviation of the left middle nasal turbinate. It abutted the nasal cavity’s lateral wall and uncinate process, resulting in the occlusion of the osteomeatal complex (Fig. 1 A and B). CT also showed opacification and reduced volume of the left anterior ethmoidal cells (including the ethmoidal bulla) with mild medial displacement and bowing of the left lamina papyracea. These findings were absent in a prior sinus CT scan performed 2 years earlier (Fig. 1 C and D) for acute sinusitis. The patient was diagnosed with ethmoid silent sinus syndrome. He was admitted to the hospital for endoscopic surgical repair. Intraoperative endoscopy revealed that the left middle turbinate was laterally deviated, with an umbilication-like deformity in its middle third. The findings were consistent with a fracture, and it was likely related to the nasopharyngeal swab testing performed 1 month before the onset of symptoms (Fig. 2). The patient underwent an uneventful partial resection of the left middle turbinate. He successfully recovered, and no residual symptoms were noted.

Fig. 1.

CT findings. Coronal (A) CT image shows a lateral deviation of the left middle nasal turbinate (arrowhead), with consequent enlargement of the common nasal meatus (asterisk) and occlusion of the osteomeatal complex. Axial (B) CT image shows opacification and reduced volume of the left anterior ethmoidal cells (long arrow). A mild medial displacement with bowing of the left lamina papyracea is also observed (short arrow). Coronal (C) and axial (D) CT images of 2 years before show that these findings were absent

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic findings. An intraoperative photograph of the left nasal cavity showed a lateral deviation of the middle turbinate (MT) with a cleft-like deformity (arrow), consistent with fracture

Discussion

Silent sinus syndrome was first reported as an imploding antrum by Montgomery in 1964 [3]. He described a case of enophthalmos caused by a mucocele in the maxillary sinus. Soparkar et al. termed this entity “silent sinus syndrome” in 1994 [4]. The terms imploding antrum, maxillary atelectasis, and, more classically, silent sinus syndrome have been used to describe the presentation of spontaneous enophthalmos and hypoglobus associated with an ipsilateral contracted maxillary sinus. Silent sinus syndrome classically refers to maxillary sinus atelectasis due to negative pressure resulting from chronic obstruction of the sinus drainage. This leads to orbital floor depression, enophthalmos, hypoglobus, enlargement of the middle nasal meatus, and facial asymmetry [5]. Evolution time of silent sinus syndrome is variable; in a review of 84 patients, the duration of symptoms prior to presentation ranged from 1 to 24 months, with a mean of 6.5 months [6]. Silent sinus syndrome is typically an idiopathic condition, but it results from trauma to the ostiomeatal complex in a few cases [7], such as in the case reported by Levine et al. [8], in which it occurred after endoscopic sinus surgery.

Ethmoidal sinus involvement in silent sinus syndrome is rare in the literature [9]. Our case was more occasional because it had a traumatic origin and was related to nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Recent retrospectives reviews assessed the complications related to swab testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fabbris et al. [2] found a low number of complications (0.16%), and Koskinen et al. [10] reported an even lower rate (0.001%). Most were related to epistaxis (in some cases severe, requiring surgical procedures and blood transfusion) or broken swab impacted in the nasal cavity [2, 10]. Other complications of nasal swabs have been described, such as nasal septum abscess, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and cribriform lamina fracture [2, 11, 12]. The nasopharyngeal swab test is more prone to complications since it requires a considerably deeper swab insertion into the patient’s nostrils, passing throughout the nasal cavity and reaching the posterior wall of the nasopharynx. While the insertion depth is 8–10 cm in the nasopharyngeal test (in adults) [13], the insertion depth is about 1.5 cm and 2 cm in the anterior nasal test and midturbinate test, respectively [2]. Moreover, nasopharyngeal swab testing is the most commonly performed among these methods, probably resulting in more complications [13]. Therefore, to our knowledge, our case represented the first report of iatrogenic ethmoid silent sinus syndrome related to a turbinate fracture caused by a nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Code availability

No software or custom code was used in this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

The work was approved by the research ethics committee of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

Informed consent

The study participant provided informed consent about participation and publication. The document on the authors’ contribution was attached separately.

We have read and understood your journal’s policies, and we believe that neither the manuscript nor the study violates any of these.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html. Accessed 30 October 2021

- 2.Fabbris C, Cestaro W, Menegaldo A, Spinato G, Frezza D, Vijendren A, Borsetto D, Boscolo-Rizzo P. Is oro/nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 detection a safe procedure? Complications observed among a case series of 4876 consecutive swabs. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42:102758. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery WW. Mucocele of the maxillary sinus causing enophthalmos. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1964;43:41–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soparkar CN, Patrinely JR, Cuaycong MJ, et al. The silent sinus syndrome: a cause of spontaneous enophthalmos. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:772–778. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illner A, Davidson HC, Harnsberger HR, Hoffman J. The silent sinus syndrome: clinical and radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:503–506. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.2.1780503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Numa WA, Desai U, Gold DR, Heher KL, Annino DJ. Silent sinus syndrome: a case presentation and comprehensive review of all 84 reported cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:688–694. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Février E, Vandersteen C, Castillo L, Savoldelli C. Silent sinus syndrome: a traumatic case. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;118:187–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine SB, Mitra S. Maxillary sinus involution after endoscopic sinus surgery in a child: a case report. Am J Rhinol. 2000;14:7–11. doi: 10.2500/105065800781602966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McArdle B, Perry C. Ethmoid silent sinus syndrome causing inward displacement of the orbit: case report. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:206–208. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109990521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koskinen A, Tolvi M, Jauhiainen M, Kekäläinen E, Laulajainen-Hongisto A, Lamminmäki S. Complications of COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab test. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147:672–674. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan CB, Schwalje AT, Jensen M, Li L, Dlouhy BJ, Greenlee JD, Walsh JE. Cerebrospinal fluid leak after nasal swab testing for coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:1179–1181. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knížek Z, Michálek R, Vodička J, Zdobinská P. Cribriform plate injury after nasal swab testing for COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147:915–917. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pondaven-Letourmy S, Alvin F, Boumghit Y, Simon F. How to perform a nasopharyngeal swab in adults and children in the COVID-19 era. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;137:325–327. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

No software or custom code was used in this article.