Abstract

Structural changes in mouse P-glycoprotein (Pgp) induced by thermal unfolding were studied by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), circular dichroism and fluorescence spectroscopy to gain insight into the solution conformation(s) of this ABC transporter that may not be apparent from current crystal structures. DSC of reconstituted Pgp showed two thermal unfolding transitions in the absence of MgATP, suggesting that each transition involved the cooperative unfolding of two or more interacting structural domains. A low calorimetric unfolding enthalpy and minimal structural changes were observed, which are hallmarks of the thermal unfolding of α-helical membrane proteins, because generally only the extramembranous regions undergo significant unfolding. Nucleotide binding increased the unfolding temperature of both transitions to the same extent, suggesting that one nucleotide binding domain (NBD) unfolds with each transition. Combined with the results from the two isolated NBDs, we propose that each DSC transition represents the cooperative unfolding of one NBD and the two contacting intracellular loops. Further, the presence of two transitions in both apo and MgATP bound wild-type Pgp suggests the NBD-dimeric conformation is transient, and that Pgp resides predominantly in the crystallographically observed inward-facing conformation with NBDs separated, even under conditions supporting continuous MgATP hydrolysis. In contrast, DSC of the vanadate-trapped MgADP·Pgp complex and the MgATP-bound catalytically inactive mutant, E552A/E1197A, show an additional transition at much higher temperature, corresponding to the unfolding of the nucleotide-trapped NBD-dimeric outward-facing conformation. The collective results indicate a strong preference for an NBD dissociated, inward-facing conformation of Pgp.

Keywords: P-glycoprotein, ABC transporter, differential scanning calorimetry, circular dichroism, intrinsic fluorescence, detergent

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

The ATP-binding cassette, ABC, transporters are a superfamily of integral membrane proteins (IMPs) that translocate across biological membranes a variety of substrates that differ widely in size and hydrophobicity [1]. They are found in all cell types and play a significant role in a large number of cellular processes [2]. Mammalian ABC transporters are exclusively exporters. P-glycoprotein (Pgp), also known as the multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) exports a variety of compounds which include hydrophobic drugs, chemotherapeutic agents and antibiotics [3, 4]. Overexpression of Pgp in cancer cells is a major contributor to the multidrug resistance phenomenon that results in chemotherapy failure [5].

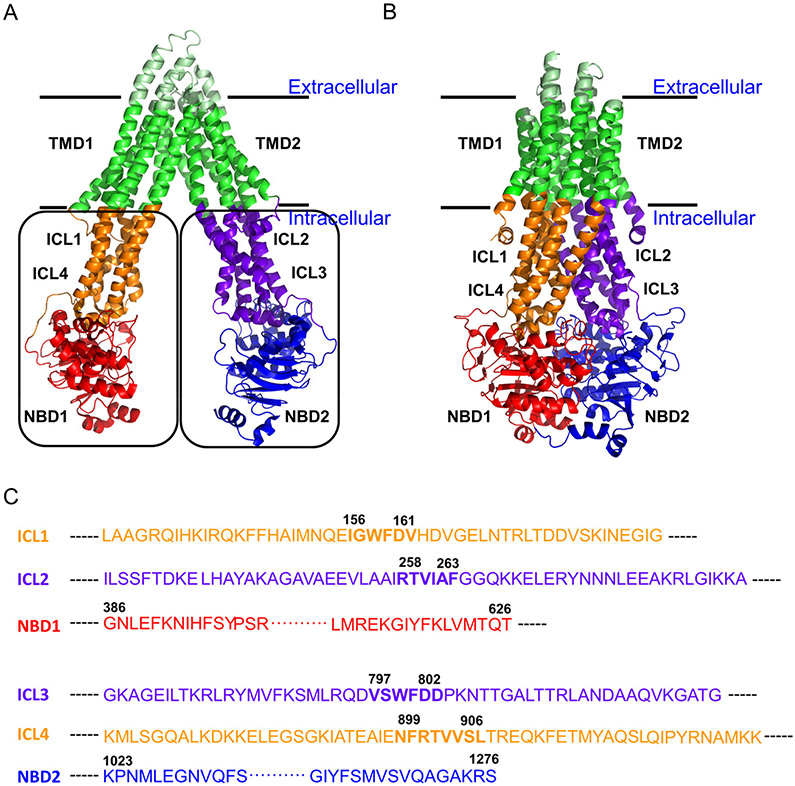

Pgp was the first eukaryotic ABC transporter to be discovered and is also the most studied [6]. It is often regarded as the prototype, and is used as a model for studying the transport mechanism of mammalian ABC exporters. Several crystal structures of Pgp from mouse (Figure 1A) [7-10] and C. elegans [11] have been solved to moderate resolutions (3.4 – 4.4 Å). All these structures are in the so-called “inward-facing” conformation wherein the molecule forms an inverted “V”-shape, with a large cavity in the center that is accessible from the cytoplasm. The core architecture of Pgp comprises two α-helical transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2) each containing six transmembrane helices that form the substrate translocation pathway, and two extramembranous nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) that bind and hydrolyze ATP to drive the transport of substrates [12] (Figure 1). The interface between the NBDs and the TMDs is formed by cytoplasmic extensions of the transmembrane helices, and like the NBDs, these reside outside the membrane (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Inward- and outward-facing conformations of Pgp.

A) Crystal structure of mouse Pgp with the TMDs shown in green, the extracellular loops shown in pale green, the ICL1 and ICL4 shown in orange with ICL4 in the front and ICL1 in the back, the ICL2 and ICL3 shown in purple blue with ICL3 in the front and ICL2 in the back, the NBD1 shown in red, and the NBD2 shown in blue (PDB ID: 4QH9) [10]. The ICLs are numbered 1 through 4 based on their positions in the primary sequence (see panel C). The ICL2 and ICL4 cross over and interacts with ICL3/NBD2 and ICL1/NBD1, respectively. The two black boxes indicate the two proposed CUs (see Discussions). B) Homology model of human Pgp [77] (PMDB ID: 75213; http://bioinformatics.cineca.it/PMDB/) based on the crystal structure of nucleotide bound Sav1866 [15]. C) Schematic representation of the extramembraouns ICL and NBD regions in terms of their locations in the primary sequence. The coupling helices are highlighted with bold font and numbering of their beginning and ending residues. The boundary residues at the water/lipid interface were obtained from the “Orientation of proteins in membranes database” - http://opm.phar.umich.edu/families.php?superfamily=17. Human and mouse Pgp share 87% sequence identity. Images generated using PYMOL.

Each of the four cytoplasmic helical extensions form a loop (termed ‘intracellular loop’ or ICL) comprising a helix –bend – helix structure. Thus, two ICL form a four-helix bundle (pairing ICL1 + ICL4 and ICL2 + ICL3). At the bend in the loop, which is distal to the membrane, a coupling helix makes contact with the NBD. The NBD1-ICL1+4 and NBD2-ICL2+3 interacting units, respectively, are schematically illustrated in Figure 1C. The NBDs are separated in the inward-facing conformation, as are the two ICL bundles associated with each NBD.

Several other ABC exporters have been crystallized in the same conformation as mouse Pgp, such as human ABCB10 [13], ABCB1 from C. merolae [14] and bacterial MsbA from E coli, V cholera, and S typhimurium [15]. The inward-facing conformation exhibits a high degree of flexibility as indicated by the variable distance between the NBDs. On the other hand, two homodimeric bacterial ABC exporters, Sav1866 [16, 17] and MsbA [15], have been crystallized in an “outward-facing” conformation with the NBDs dimerized and the substrate binding pocket accessible from the extracellular medium (Figure 1B). In the outward-facing conformation, the NBDs form a head-to-tail dimer with two bound nucleotides sandwiched between them, and the two ICL helical bundles are also in close contact with one another. Interestingly, so far no eukaryotic ABC exporter has been crystallized in the outward-facing conformation, although a medium-resolution EM structure of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) obtained in the absence of nucleotide [18] is better fit by the outward-facing Sav1866 structure than the inward-facing Pgp structure.

These crystal structures provide structural details of the substrate-binding (inward-facing) and substrate-releasing (outward-facing) conformations, while the molecular details of the conformational changes required for substrate transport and how they are coupled to ATP binding and hydrolysis remain controversial. Based on a wealth of biochemical and biophysical data available on Pgp, it is commonly accepted that both NBD1 and NBD2 are capable of hydrolyzing ATP and may do so in an alternating manner [12, 19]. One crucial piece of evidence that supports the alternating catalysis theory is the “nucleotide-occluded” conformation observed for the catalytically inactive E552A/E1197A mutant, with one non-hydrolyzed ATP tightly bound, i.e., occluded, at the NBD-heterodimer interface while the other site may contain loosely bound ATP [20]. One current debate in this field is whether the NBDs associate and dissociate (as in the “NBD monomer/dimer model” [21-23]) upon ATP binding and hydrolysis or remain in constant contact [15, 22, 24]. It has also been questioned whether the crystallized inward-facing conformation of Pgp with completely dissociated NBDs is physiologically relevant [25, 26]. However, a recent single particle electron microscopy (EM) study on mouse Pgp [27] shows that Pgp remains predominantly inward-facing with the NBDs completely dissociated even under conditions supporting continuous ATP hydrolysis.

Here we studied the interactions and cooperativity between the Pgp structural domains by thermal unfolding of the wild-type (WT) and E552A/E1197A (Mut) mouse Pgp (mdr1a) in the absence and presence of MgATP to gain insight into the solution conformation(s) of Pgp that may not be apparent from current crystal structures. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is well suited for studying the structural cooperativity of multi-domain proteins because it can resolve the number of cooperative unfolding units with different stabilities [28-33]. For example, if two structural domains strongly interact, then these two domains will cooperatively unfold as a single unit, thus identified as a “cooperative unfolding unit” or more simply, “cooperative unit” (CU). Changes in interaction strength that result in the formation of different CUs under different conditions, either comprising more (increased cooperativity) or less (decreased cooperativity) structural domains may provide clues to the change in the protein’s conformation. We have previously published the first DSC thermograms of WT mouse Pgp [34]. Our data showed that in the presence of lipids and absence of nucleotides, full-length Pgp unfolds in two distinct steps, which suggests the presence of two CUs. Since Pgp is composed of six structural domains, i.e., two TMDs, two ICL four-helical bundles, and two NBDs, accurate assignment of the structural domains that cooperatively unfold together will provide insights into the strength of interactions among the structural domains. In addition, changes in unfolding cooperativity in the absence or presence of nucleotides will not only allow for the assignment of NBD unfolding to specific DSC transitions, but will also provide insights into the protein’s conformational change during the catalytic cycle.

In the present study, we also investigated the thermal unfolding of Pgp by circular dichroism (CD) and intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy, each of which can provide information on the structural changes associated with unfolding. To assist the domain assignment, we studied the thermal unfolding of the two extramembranous NBDs of Pgp, as we previously did for human CFTR NBD1 [35]. The effect of nucleotide binding on the WT and the inactive Mut Pgp was also investigated. Based on the results, we propose structural domain assignments for each CU and infer the native solution conformations for the WT and Mut Pgp based on their inter-domain cooperativity, and response to nucleotide binding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) and decyl maltose neopentyl glycol (DMNG) were obtained from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). The phospholipids, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), and others were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). ATP, ADP and AMPPCP were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and used without further purification. The amounts of possible contaminating nucleotides in these samples were determined by an HPLC assay (see section 2.5). BioBeads were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA).

2.2. Pgp expression and purification

Codon-optimized mouse Pgp (ABCB1a; GenBank JF834158) that has the wild-type amino acid sequence and is referred to as WT Pgp in this study was expressed in P. pastoris and purified as previously described [34]. The purified protein was stored at − 80 °C in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM TCEP and 2 mM (0.1% w/v) DDM.

The E552A/E1197A mutant was generated by QuikChange mutagenesis in the codon-optimized Pgp background as previously described [36]. The protein was purified from Pichia pastoris yeast following the same protocols as for the WT Pgp [36]. The purified protein was stored at − 80 °C in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM TCEP and 2 mM (0.1% w/v) DDM

2.3. NBD cloning, expression and purification

2.3.1. Cloning and expression

The most soluble Pgp-NBD constructs published contained residues 382-628 for NBD1 [37] and residues 1023-1276 for NBD2 [38, 39]. Both encompass all secondary structural elements necessary for folding of that domain, as has recently been elucidated by the Pgp crystal structures. These two DNA sequences, optimized for E. coli expression, were de-novo synthesized and subcloned into the pSGX5_CL vector (developed by SGX Pharmaceuticals) by GeneArt (Life Technologies, USA). The target proteins were fused to a hexahistidine-SUMO protein tag (His6-Smt3) [40]. The fusion proteins were expressed in the E. coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells. Contrary to CFTR-NBD1, most of the Pgp NBD fusion proteins were found in inclusion bodies. The level of soluble expression was somewhat higher for Smt3-NBD2 than Smt3-NBD1, and sufficient amounts of purified NBD2 were obtained from the soluble fraction for thermal unfolding studies (see below).

2.3.2. Purification of NBDs from the soluble fraction

Four liters of cells were grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6 – 0.8, before 0.2 mM IPTG was added to induce protein expression. The cells were grown at 19 °C overnight, harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM arginine, 100 mM glutamic acid, 10% glycerol, 10% ethylene glycol, 5 mM TCEP, and 20 mM MgATP (Lysis Buffer), supplemented with 0.2% DMNG, protease inhibitors (Roche Inc.) and 10 U/ml benzonase nuclease (Novagen, Inc.), and lysed by sonication on ice. The cleared supernatant was purified on a 5-ml Ni-sepharose column (GE Healthcare, UAS). Ulp1 protease was added into the purified fusion protein at a protease: protein ratio of 1:100 mg/mg to cleave the His6–Smt3 tag and the mixture was dialyzed against the Stabilizing Buffer (Lysis Buffer with 2 mM TCEP instead of 5 mM) at 4 °C overnight. The sample was then passed through a second Ni-sepharose column to separate the NBD from the tag, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superdex 200 (10/300) column in Stabilizing Buffer to remove any aggregates. Fractions containing the monomeric protein (MW of 28 kDa) were combined, concentrated to approximately 1 mg/ml and stored at −80 °C. The NBD2 protein was approximately 90% pure based on SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Material Figure SF1B).

The NBD1 protein was less than 50% pure and the yield was less than 0.5 mg/L. Therefore, we decided to purify NBD1 from the guanidine-HCl solubilized inclusion bodies. This less pure batch was only used in DSC experiments for comparison with the refolded protein (Supplementary Material Figure SF1C).

2.3.3. Purification of NBD1 from guanidine-HCl solubilized inclusion bodies

The insoluble portion of the cell lysate was solubilized in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP and 6 M Guanidine-HCl (Buffer B). The cleared sample was purified on a 5-ml Ni-sepharose column in the presence of 6 M Guanidine-HCl. The purified NBD1 fusion protein was refolded by rapid dilution (1:40 fold) into the Stabilizing Buffer at 4 °C, followed by overnight dialysis at 4 °C against the same buffer and in the presence of the Ulp1 protease to cleave the His6–Smt3 tag. Purified NBD1 protein was obtained by a second Ni-sepharose column followed by SEC as described above for NBD2. The NBD1 protein was approximately 95% pure based on SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Material Figure SF1A).

2.4. Reconstitution of Pgp into proteoliposomes

2.4.1. Preparation of liposomes

A mixture containing both POPC and POPE at a ratio of 4:1 (w/w) supported the highest verapamil-stimulated ATPase activity among the phospholipids tested (Supplementary Material Figure SF2B), and was used throughout this study. POPC and POPE dissolved in chloroform were mixed at a ratio of 4:1 w/w. The lipids were first dried under a nitrogen stream to evaporate the bulk chloroform and then dried overnight under vacuum. The lipids were resuspended in the Lipid Buffer (20 mM HPEPS, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 1 mM TCEP) to give a final concentration of 50-100 mg/ml. The lipids were vortexed for 5 sec and sonicated at room temperature (~22 °C) for no more than 20 sec in a G112SP1T bath sonicator (Laboratory Supplies Co. Hicksville, NY) operated at full-power just to break up clumps. The vortexing and sonication were repeated once when needed. The mixture was then extruded 21 times through a 100-nm polycarbonate filter in a mini-extruder (from Avanti Polar Lipids) at room temperature (~22 °C) to make large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs). The size and uniformity of the LUVs were checked by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Wyatt Technologies). The LUVs were stored at 4 °C in a glass container layered with nitrogen, and usually were used within 8 hours.

2.4.2. Reconstitution of Pgp by the detergent mediated protocol

To select a detergent for reconstitution, the effect of several commonly used detergents on the thermal stability of Pgp was determined by DSC. All detergents tested, except DMNG, were more destabilizing than DDM and some caused complete denaturation (i.e., loss of DSC transition) at high concentrations (Supplementary Material Figure SF2A). Because the CMC of DMNG is lower than that of DDM, which makes detergent removal more difficult, DDM was chosen for reconstitution. A volume of 10-20 ml of 4 mg/ml LUVs were destabilized with DDM at a ratio of 1.5:1 w/w (detergent: lipids) and incubated at 37 °C for 30-60 min. The destabilized LUVs were cooled down to room temperature (~22 °C), mixed with Pgp (lipids: Pgp ratio varied from 10:1 to 30:1 w/w), and incubated at room temperature (~22 °C) for 30 min. Four to five batches of BioBeads (Bio-Rad Laboratories. Hercules, CA) with a beads: lipids ratio of 10:1 w/w were added every hour into the mixture to remove DDM. After the last addition of BioBeads, the mixture was moved to 4 °C and incubated overnight under gentle rotation. The mixture was then carefully removed from the BioBeads and transferred into a clean glass container. To obtain unilamellar vesicles again, the reconstitution mixture was extruded again through a 100-nm filter. Protein losses of >90% usually occurred during the extrusion. Extrusion did not affect the DSC profile of the protein, and was only used to eliminate interference from light scattering when collecting CD spectra.

2.4.3. Reconstitution of Pgp by other methods

For the “direct incorporation” method, Pgp (~1 mg/ml) and LUVs were mixed at a lipid: Pgp ratio of 20:1 (w/w), and incubated at 22 °C for 15 min, followed by 30 sec sonication at 4 °C in a G112SP1T bath sonicator at full power. For the “sonication” method, the Pgp/lipid mixture was sonicated at 4 °C six times in 30 sec bursts (total of 3 min). For the “freeze-thaw-sonication” method, the Pgp/lipid mixture was sonicated for 30 sec, then frozen and thawed three times in liquid nitrogen and a 22 °C water bath. The frozen-thawed sample was then sonicated at 4 °C for a total of 3 min as above. The samples were either used as is, or extruded through a 100-nm filter to make unilamellar vesicles. The association of Pgp with the liposomes was verified by centrifugation and SEC.

We found no significant difference in ATPase activity, secondary structure or thermal unfolding profiles of the resulting Pgp proteoliposomes (Supplementary Material Figure SF3), suggesting that Pgp spontaneously associates with lipids and readily incorporates into proteoliposomes independent of the method used. Because of the simplicity of the preparation and high protein recovery rate of the protein, the freeze-thaw-sonication was used to prepare proteoliposomes in most of our studies.

2.5. ATPase activity measurements

The ATPase activity of purified or reconstituted Pgp was determined at 37 °C using 10 mM MgATP by a “linked-enzyme” assay as described [34]. For the determination of inhibitory effect of other nucleotides, the assay was performed at 37 °C using 0 – 50 mM of the nucleotides and 1 mM MgATP. The nucleotide concentration that caused 50% reduction in ATPase activity was taken to be the IC50.

To detect very low level ATPase activity, purified NBDs were incubated with 10-20 mM MgATP at RT or 4 °C. At various time points, 2 μl of the reaction mixture was taken and diluted into 200 μl of 4 M guanidine-HCl. 30 μl of the diluted sample was analyzed on a 4.6 x 100 mm Synergi Polar-RP column connected to a Shimadzu HPLC system, as previously described [41]. The amounts of ATP, ADP and AMP in the mixture were determined by standard curves established using pure nucleotides. The detection limit of this HPLC assay is 0.025 μM nucleotide. The reaction rate determined by the HPLC assay was lower than that determined by the enzymatic assay, which was likely due to the inhibitory effect of ADP on the reaction.

This HPLC assay was also used to determine the purity of the commercially available nucleotides. ATP contained 3% ADP and no detectable AMP. ADP contained 3% AMP and no ATP. AMPPCP contained 0.7% AMP and no detectable ADP. At the concentrations injected, the absence of detectable levels of contaminants indicates that any possible contamination would necessarily be less than 0.025%.

2.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Calorimetry experiments were carried out in the VP-Capillary DSC System (Malvern Instruments, USA) in 0.130 mL cells at a heating rate of 1 or 2 °C/min. An external pressure of 2.0 atm was maintained to prevent possible degassing of the solutions on heating. In the cases where nucleotides were used, a concentrated stock of the nucleotides was prepared in the matching DSC buffer and added into the protein samples. The samples were incubated at 5 °C for at least 1h prior to the DSC runs. We could not conduct the experiment in high concentrations of ATP for WT Pgp because ATP hydrolysis resulted in a large exothermic peak in DSC that severely distorted the baseline, and thus, it was necessary to use a nonhydrolyzable nucleotide.

The vanadate-trapped MgADP·Pgp complexes were prepared by incubating 0.8 mg/ml Pgp proteoliposomes with 1 mM MgATP, 0.15 mM verapamil and 0.125 or 0.25 mM sodium orthovanadate at 37 °C for 30 min, as previously described [42]. The samples were cooled down in an ice bath before transferred into the DSC sample plate.

DSC data analysis was carried out using the built-in analysis modules in Origin 7 (OriginLab, LLC., USA) provided by the DSC manufacturer as described [33]. Briefly, the matching buffer scan or the protein rescan was subtracted from the protein scan to correct the instrument baseline. The resulting curve was concentration-normalized to obtain the molar heat capacity (Cp) curve. A cubic baseline that connected the linear portions before and after the transition(s) was determined and subtracted from the Cp curve, which resulted in the ‘excess Cp’ curve as those shown in Figures 4-6. The temperature corresponded to the maximum Cp was the Tm. The integrated area under the bell-shaped peak was the ΔHc. In the cases where there was more than one transition, the ΔHc of each transition was determined by fitting the curves to a multi-peak Gaussian equation provided by Origin 7.

Figure 4. Thermal Unfolding of purified NBD1 and NBD2.

A) The effect of MgATP on DSC of NBD1. Dashed line: 0.33 mg/ml NBD1 in Stabilizing Buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol, 10% ethylene glycol, 100 mM Arg, 100 mM Glu) with 20 mM MgATP. Solid line: 0.33 mg/ml NBD1 in Stabilizing Buffer with 0.07 mM MgATP. B) The effect of MgATP on DSC of NBD2. Dashed line: 0.4 mg/ml NBD2 in Stabilizing Buffer with 20 mM MgATP. Solid line: 0.76 mg/ml NBD1 in CD Buffer (Stabilizing Buffer without Arg, Glu or MgATP). C) NBD1 unfolding in CD buffer (with approximately 0.1 mM residual ATP): 1.0 mg/ml for DSC, and 1.0 mg/ml for CD in a 0.2 mm cuvette. D) NBD2 unfolding in CD buffer: 0.76 mg/ml for DSC, and 0.5 mg/ml for fluorescence, DLS, and CD in a 0.2 mm cuvette. All scan rates were 1 °C/min. All scans were performed twice. The range of Tms determined by the duplicate scans was ± 0.7 °C and the range of ΔHc was ± 15%.

Figure 6. DSC of E552A/E1197A mutant in increasing MgATP, and proposed solution conformations.

A) 0.5 mg/ml detergent-solubilized Mut, preincubated with 0, 1, 5, or 45 mM MgATP for at least 1h at 5 °C. See Figure 3 legend for buffer condition. B) 0.85 mg/ml Mut and 20 mg/ml LUV (POPC:POPE = 4:1 w/w), preincubated with 0, 1, 5, or 45 mM MgATP for at least 1h at 5 °C. The scan rate was 2 °C/min. The two transitions at the lower Tms in the presence of lipids are labeled as ‘1’ and ‘2’ in panel B. They coalesced in the absence of lipids, and this apparent single transition in panel A is labeled as ‘1, 2’ to indicate the presence of two cooperative transitions. The newly emerged highly stable transition is labeled as ‘3’ in both (A) and (B). The ΔTms are listed in Table 2. Some DSC curves are Y-translated for clarity. C) Schematic representations of the various conformations of Mut in the absence or presence of MgATP. ‘I’: inward-facing with the NBDs apart and the ICL helical bundles apart. ‘II’: inward-facing with one or two ATP bound. ‘III’: inward-facing with partial dimerization of the NBDs, but the ICL helical bundles are apart. ‘IV’: outward-facing with the NBDs dimerized, and the ICL helical bundles together.

2.7. Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD spectra were recorded in a J-815 CD spectrophotometer (JASCO, USA). Quartz cuvettes with path-lengths from 0.02 cm to 1 cm were used, and protein concentration adjusted accordingly to obtain sufficient CD signals. Typically, a protein concentration of 0.6 – 1.0 mg/ml was required in a 0.02 cm cuvette. To monitor thermal unfolding, the samples were heated at 1 or 2 °C/min, and the CD signal recorded at a fixed wavelength of 230 nm in 30 sec intervals. The secondary structural content was determined by the CDNN program [43].

The voltage applied to the photomultiplier tubes was recorded during heating to monitor possible change in the optical density of the sample. The large light scattering from lipids caused high voltage (> 500 V) and considerable noise in the CD signal of the proteoliposomes [44]. It also somewhat distorted the shape of the CD spectrum (Supplementary Material Figure SF4). Similar distortion due to the presence of lipids has been reported on other IMPs [45]. Sizing the proteoliposomes through a 100-nm filter or by sonication which produced < 100 nm proteoliposomes reduced light scattering and the CD voltage, and restored the shape of the CD spectrum to that of the detergent-solubilized state (Figure SF4). Therefore, CD data on the proteoliposomes reported here were obtained using the 100-nm or smaller proteoliposomes.

2.8. Intrinsic fluorescence

Fluorescence spectra were recorded on a CARY Eclipse fluorescence spectrometer (Agilent, USA) with excitation at 290 nm (5 nm slit width) and an emission scan from 300-450 nm in a quartz cuvette with a 1 cm path-length. The protein concentration was 0.1 – 0.4 mg/ml. To monitor thermal unfolding, the samples were heated at 1 or 2 °C/min, and the fluorescence signal recorded at a fixed wavelength of 330 nm in 30-sec intervals. To reduce the required amount of samples, thermal unfolding was also carried out in a 384 microtiter plate using a PolarStar Optima (BMG LABTECH, USA) fluorescence plate reader using the same excitation and emission wavelengths (both with 10 nm slit width). Samples were heated at 1 °C/min with an in-house fabricated integrated heating block holding the microtiter plate. The protein concentration was adjusted to 0.5 – 1.0 mg/ml to compensate for the smaller volume of 30 μl, and the protein solution topped with 15 μl of liquid wax (BioRad Laboratories) to prevent evaporation.

2.9. CD and fluorescence unfolding data analysis

Before and after the unfolding transition(s), the signal was linearly dependent on temperature, and can be represented by the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where T is the temperature in °C, Ynat is the signal of the folded state, Yunf is the signal of the unfolded state, A and C are the slopes of the lines, and B and D are the intercepts of the lines.

The fraction of unfolding, Xu at any temperature T, was calculated based on the signal Y at that temperature:

| (3) |

It is true that 1 ≥ Xu ≥ 0.

The Tm corresponded to Xu = 0.5.

3. Results

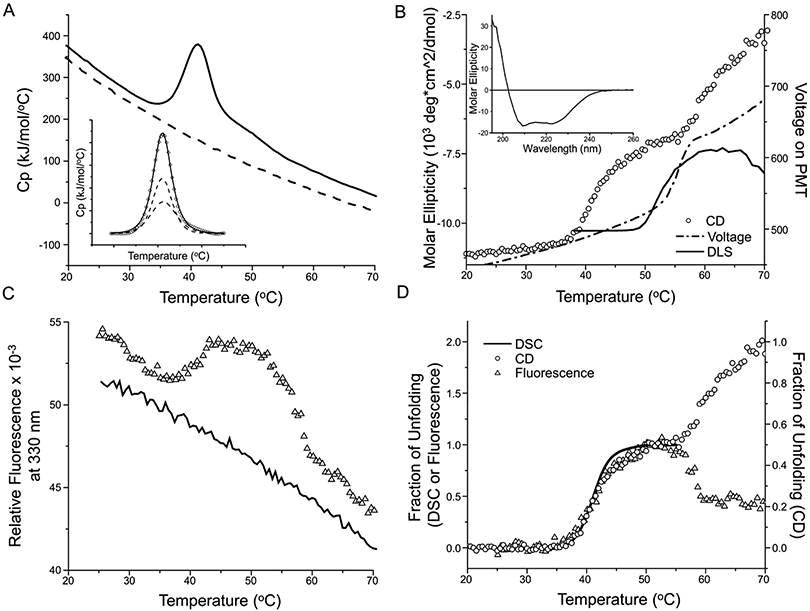

3.1. Thermal unfolding of Pgp proteoliposome consists of two cooperative transitions

Pgp proteoliposomes were obtained by reconstituting the detergent-purified Pgp into preformed large unilamellar vesicles composed of POPC and POPE in a 4:1 w/w ratio (See Materials and Methods). The protein was > 95% pure (Supplementary Material Figure SF5), and the proteoliposomes exhibited high ATPase activity similar to that previously reported [34]. A comparison of the thermal unfolding profiles of Pgp proteoliposomes obtained by DSC, far UV CD, and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy is shown in Figure 2. DSC (panel A) detected two unfolding transitions with unfolding temperatures (Tm, the temperature that corresponds to the maximum heat capacity of the DSC unfolding transition) at 47.0 ± 0.5 °C and 56.1 ± 0.4 °C, respectively. The corresponding two unfolding enthalpies (defined as the calorimetric enthalpy, ΔHc, the area under the peak) were 483 ± 39 and 603 ± 57 kJ/mol, respectively.

Figure 2. Thermal unfolding of Pgp proteoliposome.

A) DSC of 0.5 mg/ml Pgp with 10 mg/ml LUV. The solid line is the first scan and the dashed line is a rescan of the same sample that is used as baseline for enthalpy calculations. Insert: The unfolding curve (diamonds) can be deconvoluted into two transitions (‘1’ and ‘2’, dashed lines). The solid line represents the sum of the two fitted transitions. B) Thermal unfolding of 0.25 mg/ml Pgp with 5 mg/ml LUV, CD signal (circles) monitored at 230 nm in a 1 mm cuvette. The dash-dotted line is the voltage applied to the photomultiplier tubes (PMTs). The voltage is directly proportional to the optical density of the sample. C) Thermal unfolding of 0.35 mg/ml Pgp with 5.3 mg/ml LUV, intrinsic fluorescence (triangles) monitored at λex = 290 nm and λem = 330 nm in a 1 cm cuvette; the dashed line is the rescan. All samples in A-C were scanned at 1 °C/min, and had the same lipid composition of POPC: POPE = 4:1 w/w. D) Overlay of fraction of unfolding (Xu) recorded by DSC (solid line), CD (circles) and fluorescence (triangles). Xu of CD and fluorescence was computed based on Equation (3) in Materials and Methods. Xu of DSC was computed by dividing the integrated DSC data by the total calorimetric enthalpy: Xu = ΔH (T)/ΔHc.

CD showed one broad transition over the same temperature range of 40 to 60 °C as the DSC transitions (Figure 2B). The CD Tm1 was 52.3 ± 0.4 °C, approximately half-way between the two DSC transitions. The decrease in the magnitude of the molar ellipticity at 230 nm during the transition was approximately 3000 deg cm−1 x dmole−1, which was ~30% of the total ellipticity. Because α-helical structure is the main contributor to the CD spectrum at 230 nm, this would correspond to a ~30% loss in helicity.

The fluorescence spectrum of the lipid-reconstituted Pgp showed a maximum at 332 nm, suggesting that the tryptophan (Trp) residues are in nonpolar environments [46, 47]. Pgp contains eleven Trp residues, all of which may contribute to the overall fluorescence [47]. Eight are in or near the lipid bilayer and three are in the extramembranous regions, i.e., W158 is in the ICL1 coupling helix, W799 is in the ICL3 coupling helix, and W1104 is in NBD2. (Supplementary Material Figure SF6). Upon heating, the Trp fluorescence decreased almost linearly with temperature as expected from thermal quenching [48]. However, two sigmoidal transitions were apparent with Tms around 48 and 58 °C, respectively (Figure 2C). The two fluorescence transitions occurred at temperatures similar to the transitions seen by DSC, suggesting that both DSC and fluorescence spectroscopy detected the same cooperative unfolding events (Figure 2D). The Tms obtained by CD and fluorescence are listed in Table 1, along with the Tm and ΔHc obtained by DSC.

Table 1.

Thermal unfolding parameters of full-length Pgp[a]

| Tm1 (°C) | ΔHc1 (kJ/mol) |

Change in signal |

Tm2 (°C) | ΔHc2 (kJ/mol) |

Change in signal |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-Reconstituted | DSC | 47.0 ± 0.5 | 483 ± 39 | 56.1 ± 0.4 | 603 ± 57 | ||

| CD | 52.3 ± 0.4 | 28 ± 4% | |||||

| FL | 48.3 ± 0.4 | 6 ± 1% | 57.7 ± 0.3 | 4 ± 1% | |||

| Detergent-Solubilized | DSC | 41.1 ± 0.1 | 954 ± 56[b] | ||||

| CD | 42.1 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 2% | |||||

| FL | 42.7 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 1% |

The average values were calculated based on two or more measurements.

Protein unfolding enthalpy is roughly linearly dependent on temperature, i.e. the lower the Tm the lower the ΔHc [78]. The ΔHc in detergent was close to the sum of the ΔHc obtained for the two transitions in the presence of lipids, taking into account the differences in Tm.

3.2. The two thermal unfolding transitions coalesced in detergent-solubilized Pgp

The thermal unfolding profiles of purified Pgp in the detergent, 2 mM (0.1% w/v) DDM, are shown in Figure 3. Only one apparent transition was observed by DSC (Figure 3A), and in comparison to lipid-reconstituted Pgp, the Tm was significantly reduced to 41.1 ±0.1 °C.

Figure 3. Thermal unfolding of detergent-solubilized Pgp.

A) DSC of 0.5 mg/ml Pgp in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM (0.1% w/v) DDM. The solid line is the first scan and the dashed line is a rescan of the same sample that is used as baseline for enthalpy calculation. Insert: The unfolding peak (diamonds) can be deconvoluted into two transitions (dashed lines) and the solid line is the sum of the two transitions. B) CD signal at 230 nm (circles) of 0.1 mg/ml Pgp in a 1 cm cuvette. The dash-dotted line is the voltage applied on the PMTs, and the solid line is the light scattering (LS) determined by DLS (scaled and vertically shifted to compare with the voltage). Both the voltage and LS suggests protein aggregation. The insert shows the wavelength scan from 260 nm to 195 nm of 1 mg/ml Pgp in a 0.2 mm cuvette. C) Intrinsic fluorescence (triangles) of 0.5 mg/ml Pgp, monitored at λex = 290 nm and λem = 340 nm, in a 384 well microtiter plate. The solid line is the rescan. All samples in A-C were scanned at 1 °C/min. D) Overlay of the fraction of unfolding recorded by DSC (solid line), CD (circles) and fluorescence (triangles). The CD fraction is plotted with a different scale (shown on the y-axis at the right-hand side) so its first transition can overlay with the DSC and fluorescence transition.

The far-UV CD spectrum of detergent-solubilized Pgp exhibited minimums at 208 and 222 nm, typical for an α-helical protein (insert of Figure 3B). The helicity of the protein was estimated to be approximately 45% [43], in agreement with that observed in its crystal structures [10]. Two thermal unfolding transitions were observed by CD (Figure 3B). The first one was accompanied by a loss in ellipticity of 27 ± 2%, with a Tm of 42.1 ± 0.5 °C, closely matching that of the DSC transition (Table 1). A second transition appeared to follow immediately after a sharp increase in the PMT voltage profile. The increase in voltage suggested sample aggregation [49], and it coincided with a large increase in dynamic light scattering (DLS, Figure 3B), as well as visible precipitation in the sample cuvette after heating above 50 °C. Therefore, it was not possible to ascertain whether the second decrease in CD signal was due to loss of secondary structure or merely loss of protein caused by precipitation. Recently, Sharom’s group has reported a broad CD transition with a Tm of 54 °C for Pgp purified in CHAPS and no aggregation upon unfolding [50]. The difference in thermal unfolding likely suggests a difference in the conformation of the protein/detergent complex in both folded and unfolded states.

The deviation from two resolved unfolding transitions observed for Pgp proteoliposomes may be due to one of three possibilities (a) the unfolding of just one of the two CUs, (b) coalescence of the two CUs into a new, more cooperative CU which, therefore, exhibits a single unfolding transition, or (c) superpositioning of the two unfolding transitions resulting from the unfolding of two CUs with similar stabilities (Figure 3A insert). Possibilities (b) or (c) are supported by the data that suggest the same structural changes occurred during unfolding of Pgp either in detergent or lipid.

Firstly, the ΔHc (954 ± 56 kJ/mol) of the single transition for detergent solubilized Pgp was close to the sum of the ΔHc for the two transitions obtained for the Pgp proteoliposomes (483 ± 39 and 603 ± 57 kJ/mol, see Table 1 for details). Secondly, the same amount of secondary structure was lost (approximately 30%). Thirdly, the same change in intrinsic fluorescence (approximately 10% increase) accompanied the DSC transition either in detergent or lipid.

In summary, two sequential events were detected during the thermal unfolding of the detergent-solubilized Pgp: 1) Cooperative unfolding with a Tm of ~42 °C that was accompanied by partial secondary structural loss (with a helicity loss of approximately 27%) and a ~10% net increase in intrinsic fluorescence. (Figure 3D, Table 1). 2) Protein aggregation and precipitation with an onset temperature of ~50 °C. This event occurred when the cooperative unfolding transition detected by DSC was >90% complete (Figure 3B). Whether or not aggregation was accompanied by further structural changes was obscured by sample precipitation. Compared to Pgp proteoliposomes, the cooperative unfolding of detergent-solubilized Pgp appeared to involve the same extent of structural change, i.e., similar ΔHc, same % loss of secondary structure and same change in fluorescence (Table 1) but in a single transition.

3.3. Characterization of the isolated NBDs

To dissect the origins of the two Pgp DSC transitions, thermal unfolding of the isolated NBD1 and NBD2 was investigated. In order to improve solubility, NBD1 (residues 382-628) [37] and NBD2 (residues 1023-1276) [38, 39], respectively, were expressed as fusion proteins with an N-terminal hexahistidine-SUMO protein tag (His6-Smt3) [40], as we previously used for the human CFTR NBD1 (see Materials and Methods).

Both NBDs exhibited a CD spectrum resembling a helical protein (Supplementary Material Figure SF7A). The estimated helicity was 36% for NBD1 and 43% for NBD2, in good agreement with the expected 40% helicity based on the Pgp crystal structures [8, 10]. Both isolated NBDs exhibited ATPase activity (Figure SF7B) comparable with values reported by others [38, 51, 52]. The ATPase activity of Pgp was higher than the sum of activities from the two isolated domains, consistent with the presence of domain interactions that enhance ATP hydrolysis in the full-length protein [53].

3.4. Isolated NBD1 and NBD2 exhibit similar thermal unfolding profiles

DSC showed an NBD1 unfolding Tm of 36.5 °C in the presence of 20 mM MgATP that was lowered by 3.7 °C in 0.07 mM MgATP (Figure 4A). The binding affinity (Kd) of MgATP to NBD1 was estimated to be 0.5 to 1.0 mM based on the well-established relationship between unfolding temperature and ligand affinity [54, 55]. This value is similar to the reported value of 2.1 mM [51]. The NBD2 unfolded at 46.3 °C in the absence of MgATP, and the Tm remained the same in 20 mM MgATP (Figure 4B). This was unusual because binding of MgATP is expected to cause thermo-stabilization [55]. ATP binding to NBD2 was then confirmed using the fluorescently labeled ATP analog, TNP-ATP [38] (Supplementary Material Figure SF8).

Thermal unfolding of the NBDs was also monitored by CD and intrinsic fluorescence (Figure 4C and 4D). Because of optical interference, far-UV CD measurements were conducted in buffer devoid of stabilizing components such as arginine and glutamic acid, and MgATP was reduced to ≤0.1 mM. A large increase in the CD PMT voltage and DLS (not shown) suggested protein aggregation immediately followed or coincided with the DSC transition (NBD1 or NBD2, respectively), thus preventing a quantitative evaluation of the temperature dependent change in ellipticity. Nevertheless, the CD data suggested little to no change in the secondary structure of either NBD accompanied the unfolding transition detected by DSC.

An increase in fluorescence intensity accompanied the NBD2 DSC transition (Figure 4D), indicating a change in the environment of the single Trp (W1104), likely due to either or both domain unfolding and temperature-dependent protein aggregation. A small decrease in fluorescence was observed at temperatures much higher than the DSC transition and is consistent with the loss of protein due to precipitation. NBD1 does not contain a tryptophan, and as expected, no fluorescence signal was observed (data not shown).

3.5. Stabilization of full-length Pgp by nucleotides

The effects on detergent-solubilized Pgp of MgATP (1 mM), as well as nonhydrolyzable MgAMPPCP (10 mM), or MgADP (10 mM) are shown in Figure 5A. All three nucleotides increased the Tm, but by different magnitudes. Based on the magnitude of the Tm shift (ΔTm), a rank order of binding affinity was estimated to be MgATP > MgADP > MgAMPPCP [54, 55].

Figure 5. Thermo-stabilization of Pgp by nucleotides.

A) 0.5 mg/ml detergent-solubilized Pgp preincubated with different nucleotides for 1 h at 5 °C, see Figure 3 legend for buffer condition. B) 0.5 mg/ml Pgp and 10 mg/ml LUV (POPC: POPE = 4:1 w/w) preincubated with different nucleotides for 1 h at 5 °C. C) 0.42 mg/ml Pgp and 8.4 mg/ml LUV (POPC: POPE = 4:1 w/w). The sample was heated at 48 °C for 20 min and then cooled on ice and nucleotide added more than 1 h before the DSC experiments. The ΔTms with respect to each transition in the absence of nucleotide are shown on top of the transitions. All scans were performed twice. The range of Tms determined by the duplicate scans was ± 0.7 °C and the range of ΔHc was ± 15%. Some curves are Y-translated for clarity.

A similar shift to higher Tm was observed for Pgp proteoliposomes; i.e., for each nucleotide, the ΔTms of both DSC transitions were very similar to the ΔTm of the transition seen for detergent-solubilized Pgp (in Figure 5, compare panel A with panel B). The data suggest that the nucleotide binding affinity of the two CUs was similar and that Pgp’s lipid association did not significantly alter the binding affinities. Furthermore, the distribution of the total ΔHc between the two transitions observed in lipid-reconstituted Pgp remained roughly the same, which suggested that binding of the nucleotides didn’t dramatically change the domain tertiary structures or domain cooperativity. An analogous observation was made in the recently solved crystal structures of human ABCB10 [13]. In these, the protein adopts the inward-facing conformation in the presence of two non-hydrolyzable ATP with one ATP molecule bound at each NBD in the absence of a nucleotide sandwich dimer.

In order to determine if NBD unfolding contributes to one or both transitions seen in reconstituted Pgp, the effect of MgADP on partially denatured Pgp proteoliposomes was studied. The Pgp proteoliposomes were heated in a 48 °C water bath for 20 min to eliminate the first DSC transition but preserve most of the second transition. Upon the addition of 10 mM MgADP, the remaining second transition exhibited the same Tm shift of +6 °C as the fully intact protein in the presence of the same nucleotide (Figure 5C), suggesting the remaining CU is capable of binding nucleotides and therefore contains an NBD.

Urea has been shown to affect the stability of different domains or subunits of ABC transporters differently [56], and its effect on the two CUs of Pgp was investigated here. The two CUs exhibited different stabilities towards urea denaturation that correlated with their thermal stability. As shown in Figure SF9A of the Supplementary Material, both DSC transitions shifted to lower Tm in the presence of increasing amount of urea. At a concentration of 5 M urea, the low temperature transition was no longer detectable, while the higher temperature transition shifted down to approximately 40 °C. Again, 10 mM MgADP shifted this remaining transition by +6 °C (Figure SF9B). The data suggest that the partially denatured state reached by either heating or urea denaturation was similar and was capable of binding nucleotides.

3.6. Appearance of an additional conformation upon ATP binding to the E552A/E1197A mutant

We engineered the catalytic carboxylate Mut Pgp that is known to exhibit drastically reduced ATP hydrolysis (by 1,000-fold) and to produce an occluded state with one MgATP tightly bound in the Pgp catalytic sites [20, 57-59]. This occluded state is thought to represent the pre-hydrolysis conformation with the two NBDs dimerized, and two ATP molecules sandwiched between the NBD dimer, one of which is poised for hydrolysis. Similarly, removal of the catalytic carboxylate in isolated NBDs can produce a stable nucleotide sandwich dimer, and has allowed crystallization of the NBD dimer of several ABC transporters [60, 61]. We hypothesize that the thermal stability and cooperativity of the NBD-dimerized Pgp conformation (i.e., outward facing) that results from ATP binding will be very different from the NBD-dissociated Pgp conformation (i.e., inward facing).

In detergent solution, the Mut Pgp exhibited one transition in the absence of ATP (Figure 6A, bottom curve), similar to WT Pgp2. Upon addition of 1 mM MgATP, a second new transition emerged at a much higher temperature, shifted by an impressive 25 °C, with a Tm greater than 60 °C. With increasing MgATP, the new transition shifted to even higher Tm (>70 °C), and its ΔHc increased (Table 2). Concomitantly, the lower Tm transition (around 40 °C) also shifted to higher temperatures, but the ΔTm was smaller. Moreover, the ΔHc of the lower transition decreased, while the sum ΔHc of the two transitions (~1000 kJ/mol) remained roughly the same (Table 2), suggesting a shift in the population of molecules.

Table 2.

ΔTm of E552A/E1197A in the presence of nucleotides[a]

| ΔTm1 (°C)[a] | ΔTm2 (°C) [b] | ΔTm3 (°C) [c] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent-Solubilized | 1 mM MgATP | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 24.8 ± 0.2 | |

| 5 mM MgATP | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 33.0 ± 0.2 | ||

| 45 mM MgATP | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 35.1 ± 0.3 | ||

| Lipid-Reconstituted | 1 mM MgATP | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 24.2 ± 1.7 |

| 5 mM MgATP | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 27.4 ± 0.4 | |

| 45 mM MgATP | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 30.6 ± 0.1 |

The average values were calculated based on two measurements.

See Figure 6 for the numbering of the transitions.

In the detergent-solubilized Pgp, DSC transitions 1 and 2 coalesced and only one ΔTm is reported. In Pgp proteoliposomes, the two Tms were estimated by two-peak deconvolution (see Materials and Methods).

The reported ΔTm3 is with respect to transition 1 in the absence of nucleotide.

Similar changes were observed for Mut Pgp proteoliposomes (Figure 6B). Without MgATP, two transitions were observed, as seen for WT Pgp proteoliposomes. Upon addition of MgATP, a third transition appeared at a much higher temperature with a Tm of >65 °C and this new transition shifted to even higher temperatures with increasing MgATP, as it did in detergent solution. These data are consistent with the appearance of a new population of protein molecules in a different and much more stable conformation (i.e., the ‘high-Tm, single-transition’ population). Both of the two original low-Tm transitions shifted to higher Tm in the presence of increasing MgATP, and the ΔTms at 1 mM MgATP were similar to those of WT Pgp under the same condition (Table 2 and Figure 5). However, with further increase in MgATP, the two lower transitions appeared to merge together. The simultaneous increase in ΔHc of the high-Tm transition and decrease in ΔHc of the two lower-Tm transitions suggest a shift in the population of Mut Pgp molecules from the less stable to the more stable conformation upon binding of MgATP. These two conformationally distinct populations are apparently in slow exchange on the DSC time scale since they unfolded independently from each other.

A high-Tm transition was also observed for the vanadate-trapped MgADP complex of WT Pgp [42] (Figure SF10 of the Supplementary Material). Its Tm was similar to that of the high-Tm transition observed in the Mut Pgp (i.e., between 70-75 °C). As vanadate concentration increased, the ΔHc of the high-Tm transition also increased and the ΔHc of the two lower-Tm transitions simultaneously decreased. These observations suggest a shift in the population of WT Pgp to the vanadate-trapped conformation, which was more stable, and similar to the MgATP bound Mut Pgp conformation. A negative (i.e., exothermic) transition was observed in the presence of ATP (Figure SF10), which was likely due to ATP hydrolysis. We determined the extent of ATP hydrolysis under the same conditions as the DSC experiments (Supplementary Figure SF11). The data showed that temperature-stimulated ATP hydrolysis ceased at the temperature of Pgp denaturation as evidenced by DSC. While ATP hydrolysis was overall low under these conditions, stimulation coincided with the occurrence of the negative DSC peak. Because the negative peak hindered the deconvolution of the unfolding transitions and the accurate determination of ΔHc, we sought conditions that were more straight-forward to analyze, such as using the nonhydrolyzable AMPPCP. The high-Tm transition was indeed observed in the presence of supersaturating concentrations of 45 mM (and not 10 mM) AMPPCP (Figure 5B top DSC curve).

Overall, the data in the presence of vanadate for the WT Pgp and in the presence of MgATP for the Mut Pgp are consistent with the formation of a very thermostable nucleotide sandwich dimer conformation that has been proposed for this mutation [20, 57-59].

4. Discussion

It is generally accepted that thermal unfolding of α-helical IMPs is different from that of soluble proteins by the following two features: 1) membrane embedded helices usually do not lose helicity in the temperature range where protein unfolding is monitored; 2) the unfolding enthalpy (ΔHc) can be largely accounted for by the unfolding of the extramembranous portions only [62-64] (reviewed by Haltia and Freire, 1995 [65] and Yang and Brouillette, 2016 [33]). The DSC, CD and intrinsic fluorescence data obtained in this study suggest that the thermal unfolding of full-length Pgp also shares these common features as described next.

The total unfolding enthalpy of Pgp is extremely low compared to that of soluble proteins of the same size. The extramembranous portions of Pgp represent approximately 60% of the full-length protein, which consist of the intracellular two water-soluble NBDs and the two α-helical ICL bundles, and the six extracellular loops (ECLs). The ECLs are short, accounting for less than 5% of the total extramembranous residues, and therefore, cannot significantly contribute to the overall unfolding enthalpy. If the specific enthalpy is accounted for by only the intracellular portions, the measured specific enthalpy of 13.8 J/g is still much lower than the 30-40 J/g observed for soluble proteins [33, 65]. This is likely due to the low unfolding enthalpy of the NBDs, which for the isolated domains were 11 J/g (~300 kJ/mol) for NBD1 and 4.6 J/g (~125 kJ/mol) for NBD2. Because the unfolding enthalpy of the NBDs alone can’t account for the observed total unfolding enthalpy of Pgp (~1000 kJ/mol), it stands to reason that the unfolding of the extramembranous ICLs contribute the remainder.

The cooperative unfolding of the isolated NBDs resulted in minimal changes in their secondary structure (Figure 4). However, thermal unfolding of the full-length Pgp resulted in the loss of approximately 27-28% of the α-helical structure (Figures 2 and 3). Therefore, these changes in secondary structure can only be attributed to the unfolding of the two ICL bundles, which together contribute approximately 25-30% to the total helicity observed in the crystal structure [10]. In summary, the unfolding enthalpy and secondary structural changes that accompany Pgp thermal unfolding are consistent with participation of only the NBDs and the ICLs.

4.1. Assignment of Structural Domains to the two CUs identified in Pgp proteoliposomes

Each of the two resolved DSC transitions seen for Pgp proteoliposomes are due to the thermal unfolding of one CU each, which in turn comprise more than one structural domain, as discussed above. Because these two DSC transitions have nearly identical calorimetric enthalpies, it is likely that the two CUs have a similar size and a similar secondary and tertiary structural content [66, 67]. Based on the crystal structures of Pgp (Figure 1A), we propose that each CU contains one NBD and one ICL helical bundle, i.e. CU1 contains NBD1 and the interacting ICL1/ICL4 helical bundle, and CU2 contains NBD2 and the ICL2/ICL3 helical bundle. Our proposed assignment is consistent with the even distribution between the two DSC transitions of the thermally induced secondary structural changes, which mainly originated from the ICLs (Figure 2D). It is also consistent with the two fluorescence transitions that coincided with the two DSC transitions. These may be attributed to the three extramembranous Trps located in the solvent inaccessible coupling helix at the ICL1-NBD1 (W158) and the ICL3-NBD2 (W799) interface, respectively, and in the NBD2 backbone (W1104) (See Supplementary Material Figure SF6 for positions in the Pgp structure). Increase of the W1104 fluorescence intensity upon unfolding of the isolated NBD2, without a shift in the maximal emission wavelength (λmax), is consistent with loss of quenching from a nearby amino acid residue (possibly K1023), or alternatively, this Trp was exposed to solvent upon unfolding but then became reburied as a result of domain aggregation. The Trps in the ICL1 and ICL3 coupling helices may experience a similar change in environment upon the unfolding of the two CU and contribute to the change in fluorescence intensity accompanying each respective DSC transition. Therefore, we infer from the CU assignment that, in the absence of ATP, Pgp is in the crystallographically observed inward-facing conformation with NBDs separated. Because isolated NBD2 unfolded at higher temperatures than NBD1, we speculate that CU1 and CU2 may be assigned to DSC transition 1 and DSC transition 2, respectively (Figures 2 and 5).

An alternative assignment considers the possibility that the two DSC transitions in the presence of lipids represent two conformationally distinct Pgp populations, rather than one homogenous population with a single conformation. Regarding this alternative, it is interesting that Pgp adopts a different conformation when in detergent (one apparent DSC transition) versus reconstituted in lipid (two DSC transitions). It’s possible that transition 1 seen in lipid corresponds to the single transition in detergent, and transition 2 corresponds to the unfolding of a somewhat more stable conformation, possibly some form of a ‘semi’ NBD-dimerized conformation (for example state III in Fig. 6C) because domain interactions can increase stability. On the other hand, so far, all available crystal structures of full-length ABC transporters or isolated NBDs show the NBD nucleotide sandwich dimer only in the presence of nucleotides; and it has been proposed that the two ATP molecules act as “molecular glue” that stabilize the dimer [60]. Furthermore, in recent single-particle analyses of negatively stained Pgp, Moeller et al. found less than 3% of molecules in the outward-facing NBD-dimer conformation in the absence of nucleotide at ambient temperature. That population did not increase much after incubation with MgATP or the non-hydrolyzable MgAMP-PNP analog (<4% of the total molecules) [27]. Here we observe an almost even distribution of the calorimetric enthalpy between the two peaks that remained essentially the same in the presence of MgATP or up to 10 mM AMPPCP (see below), which also argues against the alternative transition assignment, in agreement with the Moeller et al. study.

4.2. Unfolding cooperativity in the presence of ATP and its physiological implications

According to the alternating access model [22, 23]. Pgp switches between the inward-facing conformation with the two CUs separated and the outward-facing conformation with tightly dimerized NBDs and the CUs associated. This is simplified as a two-state equilibrium between conformers II and IV in Figure 6C. In the NBD monomer/dimer models, the NBDs dimerize upon ATP binding and completely dissociate upon ATP hydrolysis [23, 68-71]; whereas in the constant-contact models, the NBDs remain in contact during the hydrolysis cycle, and the power stroke results from smaller conformational changes at the NBD1-NBD2 interface [15, 24]. Crystal structures of asymmetric ABC exporters (those with only one catalytically active ATP site) have also shown the existence of intermediate conformations in line with constant-contact models (for example conformer III in Figure 6C) [72, 73].

As we have observed in this study, DSC may detect four major conformations in the Mut Pgp proteoliposomes (see the assignment of DSC transitions to corresponding conformations in Figure 6B and 6C). In the absence of nucleotide, DSC of the Mut protein showed two transitions (1 and 2) corresponding to conformer I with the two CUs separated. In the presence of 1 mM MgATP, a concentration ~100 times higher than the Kd of 9.2 μM [20], a new, single DSC transition at a much higher Tm (transition 3) emerged. The high stability and high cooperativity of transition 3 is consistent with the outward-facing conformation (conformer IV) proposed by Thombline et al. [20] for Mut Pgp. Furthermore, transitions 1 and 2 appeared to merge at MgATP concentrations of 5 mM and above (Figure 6B). We interpret this feature to indicate partial NBD dimerization as seen in asymmetric ABC transporter structures (conformer III, Figure 6C). A limited interaction between the NBD/ICL bundles would increase the overall cooperativity. The remaining relatively low Tm of the merged transitions 1 and 2 is consistent with this population of protein being still inward facing, with the two CUs largely separated. However, as an alternative interpretation at very high concentrations of ATP, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that ATP binding to low-affinity site(s) is a complication.

In WT Pgp proteoliposomes, conformer IV (transition 3, Figure 5B) was also detected not only in the presence of very high concentrations (45 mM) of the non-hydrolyzable MgAMPPCP, but also in the presence of 1 mM MgATP with verapamil and vanadate, i.e., conditions that trap the reaction intermediate (Figure SF 11) [42]. Conformer II was observed under conditions supporting continuous hydrolysis with 1 mM MgATP, and in the presence of other nucleotides (10 mM MgAMPPCP or post hydrolysis product MgADP). Together, the prevalence of the two separated CUs (transitions 1 and 2) under all conditions tested suggests that the two NBDs do dissociate and, consequently, supports a monomer/dimer model. WT Pgp can hydrolyze ~12 ATP molecules per min under physiological conditions (at 37 °C) in the presence of mM concentrations of ATP (Figure SF7). Therefore, since conformation IV was not detected within the time scale of the DSC scan (1 °C/min), we conclude there is a fast interconversion between the inward-facing and outward-facing conformations, and that the NBD dimer conformation IV is transient. The fast interconversion among Pgp conformational states in the presence of nucleotides and transport substrates has also been observed by measuring the distance between the two NBDs using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) [74, 75]. The FRET study [74] confirmed that in the absence of nucleotide, the two NBDs are separated (i.e., conformation I). Upon the addition of 1 mM MgATP, the ensemble-averaged distance between the two NBDs decreased, suggesting that Pgp spends some fraction of time in the NBD-associated state. However, the observed fluorescence difference with or without MgATP was very small, consistent with the majority of the bulk sample being in the NBD-separated conformation, as we have observed in the present study. However, a recent Cryo-EM study on human Pgp in detergent [76] has detected both the inward-facing and outward-facing conformations even in the absence of nucleotides, which appears to contradict the results of Moeller et al. [27] and the present study. We note, however, that this cryo-EM study was conducted in the presence of the conformation-specific antibody UIC2. It is possible that binding of the antibody significantly slows down the interconversion of the inward-facing and outward-facing conformations in the cryo-EM study. Consequently, the present studies cannot be directly compared to those of Frank et al [76].

In Mut Pgp proteoliposomes, DSC detected both conformers II and IV in the presence of MgATP, suggesting that interconversion between the inward-facing and outward-facing conformations also occurred during the DSC time scale albeit at a slower rate than for WT Pgp (Figure 6B). The proposed slower rate of interconversion is consistent with the much slower (~425-fold slower, V=0.005 μmol/min/mg) ATP hydrolysis rate reported for this catalytically inactive mutant. Even at super-saturating MgATP concentrations of 45 mM (~5000 times Kd for the Mut Pgp), the DSC transition 3 (conformer IV) only accounted for about half the total unfolding enthalpy. The data suggest that during a DSC scan, NBD dimer dissociation may occur with or without MgATP hydrolysis, but once dissociated, denaturation is inevitable as the dissociated CUs are much less thermostable. The fact that only about 50% of the population of molecules are found in the highly thermostable NBD dimer conformation (conformer IV), even in the Mut Pgp, reinforces the notion that Pgp has a strong preference for an NBD dissociated, inward-facing conformation. This conclusion may explain the lack, so far, of a structure in the outward-facing conformation for Pgp and other mammalian ABC exporters. On the other hand, our study suggests that through manipulation of these proteins’ ATP binding/hydrolysis characteristics, the outward-facing conformation can be populated significantly or even become the predominant conformation and thus be more amenable to structure determination. The ability of our methods to detect more than one conformation simultaneously under physiological conditions, and without the need for chemical labelling, makes it a valuable alternative to crystallographic methods which are relatively more difficult to implement and can only take static snapshots of a dynamic protein.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

P-glycoprotein thermal unfolding data indicate two cooperative unfolding units.

Each cooperative unit contains one NBD and two contacting intracellular loops.

P-glycoprotein is predominantly inward-facing under continuous ATP hydrolysis.

Outward-facing conformation in wild-type P-glycoprotein is transient.

Outward-facing conformation is detected by DSC only when ATP hydrolysis is disabled.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics CFTR 3D Structure Consortium for insightful discussions. This work was supported, in part, by CFFT grants to Drs. C. Brouillette and I. Urbatsch, and by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant RGM102928 to I. Urbatsch. We thank Jianping Bai for excellent technical assistance with Pgp purifications, and Joshua Thomas for membrane preparations. Access to the Cap-DSC was provided by the Biocalorimetry Lab supported by the Shared Facility Program of the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center, Grant # 316851.

List of Abbreviations

- AMPPCP

β, γ-Methylene ATP

- CD

Circular Dichroism

- CU

Cooperative Unit

- CFTR

Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator

- DDM

n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside

- ΔHc

Calorimetric Enthalpy

- DLS

Dynamic Light Scattering

- DMNG

Decyl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol

- DSC

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

- ΔTm

Shift in Thermal Unfolding Temperature

- His6–Smt3

Hexahistidine-SUMO protein tag

- ICL

Intracellular Loop

- IMP

Integral Membrane Protein

- LS

Light Scattering

- LUV

Large Unilamellar Vesicle

- MDR

Multidrug Resistance

- Mut

E552A/E1197A Mutant

- NBD

Nucleotide Binding Domain

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein

- PMT

Photomultiplier tubes

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPE

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- SEC

Size Exclusion Chromatography

- Tm

Thermal Unfolding Temperature

- TMD

Transmembrane Domain

- WT

Wild Type

Footnotes

The spectroscopically determined Tm is defined as the temperature that corresponds to a 50% change in the spectroscopic property being monitored during unfolding.

Compared to the WT, the Tm of the mutant was somewhat lower by 2-3 °C, but the ΔHc were similar to that of the WT.

References

- 1.ter Beek J, Guskov A, Slotboom DJ. (2014) Structural diversity of ABC transporters. J Gen Physiol. 2014 April;143(4):419–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins CF (1992) ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu. Rev. Cell 24 Biol 8, 67–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean M, Rzhetsky A and Allikmets R (2001) The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 11, 1156–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharom FJ. (2011) The P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter. Essays Biochem. 50(1):161–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman MM, Ling V (2006) The molecular basis of multidrug resistance in cancer: the early years of P-glycoprotein research. FEBS Lett 580: 998–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharom FJ. (2014) Complex interplay between the P-glycoprotein multidrug efflux pump and the membrane: its role in modulating protein function. Front Oncol. 4:41. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aller SG, Yu J, Ward A, Weng Y, Chittaboina S, Zhuo R, Harrell PM, Trinh YT, Zhang Q, Urbatsch IL, Chang G. (2009) Structure of P-glycoprotein reveals a molecular basis for poly-specific drug binding. Science. 323(5922):1718–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward AB, Szewczyk P, Grimard V, Lee CW, Martinez L, Doshi R, Caya A, Villaluz M, Pardon E, Cregger C, Swartz DJ, Faison PG, Urbatsch IL, Govaerts C, Steyaert J, Chang G. (2013) Structures of P-glycoprotein reveal its conformational flexibility and an epitope on the nucleotide-binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110(33):13386–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Jaimes KF, Aller SG. (2014) Refined structures of mouse P-glycoprotein. Protein Sci. 23(1):34–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szewczyk P, Tao H, McGrath AP, Villaluz M, Rees SD, Lee SC, Doshi R, Urbatsch IL, Zhang Q, Chang G. (2015) Snapshots of ligand entry, malleable binding and induced helical movement in P-glycoprotein. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 71(3):732–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin MS, Oldham ML, Zhang Q, Chen J. (2012) Crystal structure of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein from Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 490(7421):566–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees DC, Johnson E, Lewinson O. (2009) ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10(3):218–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shintre CA, Pike AC, Li Q, Kim JI, Barr AJ, Goubin S, Shrestha L, Yang J, Berridge G, Ross J, Stansfeld PJ, Sansom MS, Edwards AM, Bountra C, Marsden BD, von Delft F, Bullock AN, Gileadi O, Burgess-Brown NA, Carpenter EP. (2013) Structures of ABCB10, a human ATP-binding cassette transporter in apo- and nucleotide-bound states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110(24):9710–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodan A, Yamaguchi T, Nakatsu T, Sakiyama K, Hipolito CJ, Fujioka A, Hirokane R, Ikeguchi K, Watanabe B, Hiratake J, Kimura Y, Suga H, Ueda K, Kato H. (2014) Structural basis for gating mechanisms of a eukaryotic P-glycoprotein homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111(11):4049–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward A, Reyes CL, Yu J, Roth CB, Chang G. (2007) Flexibility in the ABC transporter MsbA: Alternating access with a twist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104(48):19005–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson RJ, Locher KP. (2006) Structure of a bacterial multi drug ABC transporter. Nature 443(7108):180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson RJ, Locher KP. (2007) Structure of the multidrug ABC transporter Sav1866 from Staphylococcus aureus in complex with AMP-PNP. FEBS Lett. 581(5):935–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg MF, O'Ryan LP, Hughes G, Zhao Z, Aleksandrov LA, Riordan JR, Ford RC. (2011) The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR): three-dimensional structure and localization of a channel gate. J Biol Chem. 286(49):42647–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senior AE. (2011) Reaction chemistry ABC-style. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 108(37):15015–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tombline G, Muharemagić A, White LB, Senior AE. (2005) Involvement of the "occluded nucleotide conformation" of P-glycoprotein in the catalytic pathway. Biochemistry. 44(38):12879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins CF, Linton KJ. (2004) The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11(10):918–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollenstein K, Dawson RJ, Locher KP. (2007) Structure and mechanism of ABC transporter proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 17: 412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins CF. (2007) Multiple molecular mechanisms for multidrug resistance transporters. Nature. 446:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones PM, George AM. (2009) Opening of the ADP-bound active site in the ABC transporter ATPase dimer: evidence for a constant contact, alternating sites model for the catalytic cycle. Proteins. 75(2):387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones PM, George AM. (2013) Mechanism of the ABC transporter ATPase domains: catalytic models and the biochemical and biophysical record. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 48(1):39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones PM, George AM. (2014) A reciprocating twin-channel model for ABC transporters.Q. Rev. Biophys 47, 189–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moeller A, Lee SC, Tao H, Speir JA, Chang G, Urbatsch IL, Potter CS, Carragher B, Zhang Q. (2015) Distinct conformational spectrum of homologous multidrug ABC transporters. Structure. 23(3):450–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Privalov PL (1982) Stability of proteins: Proteins which do not present a single cooperative system. Adv. Prot. Chem 35:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy KP, Freire E. (1992) Thermodynamics of structural stability and cooperative folding behavior in proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 43:313–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nevzorov I, Redwood C, Levitsky D. (2008) Stability of two beta-tropomyosin isoforms: effects of mutation Arg91Gly. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 29(6-8):173–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamazares E, Clemente I, Bueno M, Velázquez-Campoy A, Sancho J. (2015) Rational stabilization of complex proteins: a divide and combine approach. Sci Rep. 5:9129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulthess T, Schönfeld HJ, Seelig J. (2015) Thermal unfolding of apolipoprotein A-1. Evaluation of methods and models. Biochemistry. 54(19):3063–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z, Brouillette CG. (2016) A Guide to Differential Scanning Calorimetry of Membrane and Soluble Proteins in Detergents. Methods Enzymol. 567:319–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai J, Swartz DJ, Protasevich II, Brouillette CG, Harrell PM, Hildebrandt E, Gasser B, Mattanovich D, Ward A, Chang G, Urbatsch IL. (2011) A gene optimization strategy that enhances production of fully functional P-glycoprotein in Pichia pastoris. PLoS One. 6(8):e22577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Protasevich I, Yang Z, Wang C, Atwell S, Zhao X, Emtage S, Wetmore D, Hunt JF, Brouillette CG (2010) Thermal unfolding studies show the disease causing F508del mutation in CFTR thermodynamically destabilizes nucleotide-binding domain 1. Protein Sci. 19:1917–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swartz DJ, Mok L, Botta SK, Singh A, Altenberg GA, Urbatsch IL. (2014) Directed evolution of P-glycoprotein cysteines reveals site-specific, non-conservative substitutions that preserve multidrug resistance. Biosci Rep. 34(3). pii: e00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr ID, Berridge G, Linton KJ, Higgins CF, Callaghan R. (2003) Definition of the domain boundaries is critical to the expression of the nucleotide-binding domains of P-glycoprotein. Eur Biophys J. 32(7):644–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baubichon-Cortay H, Baggetto LG, Dayan G, Di Pietro A. (1994) Overexpression and purification of the carboxyl-terminal nucleotide-binding domain from mouse P-glycoprotein. Strategic location of a tryptophan residue. J Biol Chem. 269(37):22983–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Wet H, McIntosh DB, Conseil G, Baubichon-Cortay H, Krell T, Jault JM, Daskiewicz JB, Barron D, Di Pietro A. (2001) Sequence requirements of the ATP-binding site within the C-terminal nucleotide-binding domain of mouse P-glycoprotein: structure-activity relationships for flavonoid binding. Biochemistry. 40(34):10382–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atwell S, Brouillette CG, Conners K, Emtage S, Gheyi T, Guggino WB, Hendle J, Hunt JF, Lewis HA, Lu F, Protasevich II, Rodgers LA, Romero R, Wasserman SR, Weber PC, Wetmore D, Zhang FF, Zhao X. (2010) Structures of a minimal human CFTR first nucleotide-binding domain as a monomer, head-to-tail homodimer, and pathogenic mutant. Protein Eng Des Sel. 23(5):375–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moro WB, Yang Z, Kane TA, Zhou Q, Harville S, Brouillette CG, Brouillette WJ. (2009) SAR studies for a new class of antibacterial NAD biosynthesis inhibitors. J Comb Chem. 11(4):617–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urbatsch IL, Tyndall GA, Tombline G, Senior AE. (2003) P-glycoprotein catalytic mechanism: studies of the ADP-vanadate inhibited state. J Biol Chem. 278(25):23171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.CDNN: CD Spectra Deconvolution, Version 2.1. Universität - Böhm; – 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ladokhin AS, Fernández-Vidal M, White SH. (2010) CD spectroscopy of peptides and proteins bound to large unilamellar vesicles. J Membr Biol. 236(3):247–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Findlay HE, Rutherford NG, Henderson PJ, Booth PJ. (2010) Unfolding free energy of a two-domain transmembrane sugar transport protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107(43):18451–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu R, Siemiarczuk A, Sharom FJ. (2000) Intrinsic fluorescence of the P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter: sensitivity of tryptophan residues to binding of drugs and nucleotides. Biochemistry. 39(48):14927–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swartz DJ, Weber J, Urbatsch IL. (2013) P-glycoprotein is fully active after multiple tryptophan substitutions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1828(3):1159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robbins RJ, Fleming GR, Beddard GS, Robinson GW, Thistlethwaite PJ, Woolfe GJ. (1980) Photophysics of aqueous tryptophan: pH and temperature effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc 102(20):6271–6279. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benjwal S, Verma S, Röhm KH, Gursky O. (2006) Monitoring protein aggregation during thermal unfolding in circular dichroism experiments. Protein Sci. 15(3):635–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clay AT, Lu P, Sharom FJ. (2015) Interaction of the P-Glycoprotein Multidrug Transporter with Sterols. Biochemistry. 54(43):6586–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dayan G, Baubichon-Cortay H, Jault JM, Cortay JC, Deléage G, Di Pietro A. (1996) Recombinant N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain from mouse P-glycoprotein. Overexpression, purification, and role of cysteine 430. J Biol Chem. 271(20):11652–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qian F, Wei D, Liu J, Yang S. (2004) Molecular Model and ATPase Activity of Carboxyl-Terminal Nucleotide Binding Domain from Human P-Glycoprotein. Biochemistry (Mosc). 71 Suppl 1:S18–24, 1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loo TW, Clarke DM. (1994) Reconstitution of drug-stimulated ATPase activity following co-expression of each half of human P-glycoprotein as separate polypeptides. J Biol Chem. 269(10):7750–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plotnikov V, Rochalski A, Brandts M, Brandts JF, Williston S, Frasca V, Lin LN. (2002) An autosampling differential scanning calorimeter instrument for studying molecular interactions. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 1(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waldron TT, Murphy KP. (2003) Stabilization of proteins by ligand binding: application to drug screening and determination of unfolding cooperatives. Biochemistry. 42(17):5058–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Di Bartolo ND, Hvorup RN, Locher KP, Booth PJ (2011) In vitro folding and assembly of the Escherichia coli ATP-binding cassette transporter, BtuCD. J Biol Chem 86:18807–18815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urbatsch IL, Gimi K, Wilke-Mounts S, Senior AE. (2000) Investigation of the role of glutamine-471 and glutamine-1114 in the two catalytic sites of P-glycoprotein. Biochemistry. 39(39):11921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]