Abstract

Aims

The purpose of this study was to examine whether pandemic exposure impacted unmet social and diabetes needs, self-care behaviors, and diabetes outcomes in a sample with diabetes and poor glycemic control.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional analysis of participants with diabetes and poor glycemic control in an ongoing trial (n = 353). We compared the prevalence of unmet needs, self-care behaviors, and diabetes outcomes in successive cohorts of enrollees surveyed pre-pandemic (prior to March 11, 2020, n = 182), in the early stages of the pandemic (May–September, 2020, n = 75), and later (September 2020–January 2021, n = 96) stratified by income and gender. Adjusted multivariable regression models were used to examine trends.

Results

More participants with low income reported food insecurity (70% vs. 83%, p < 0.05) and needs related to access to blood glucose supplies (19% vs. 67%, p < 0.05) during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels. In adjusted models among people with low incomes, the odds of housing insecurity increased among participants during the early pandemic months compared with participants pre-pandemic (OR 20.2 [95% CI 2.8–145.2], p < 0.01). A1c levels were better among participants later in the pandemic than those pre-pandemic (β = −1.1 [95% CI −1.8 to −0.4], p < 0.01), but systolic blood pressure control was substantially worse (β = 11.5 [95% CI 4.2–18.8, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Adults with low-incomes and diabetes were most impacted by the pandemic. A1c may not fully capture challenges that people with diabetes are facing to manage their condition; systolic blood pressures may have worsened and problems with self-care may forebode longer-term challenges in diabetes control.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Social determinants of health, Diabetes, Self-management, Outcomes

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic in the US has led to drastic measures to protect population health. These measures have been especially important to protect the health of vulnerable populations such as those with diabetes, who are at increased risk of severe complications from COVID-19 infection. However, these unprecedented measures have had variable socioeconomic impacts. Early in the pandemic, the number of uninsured adults increased 39% more than the highest level previously recorded [1]. Four out of 10 low-income Americans were struggling to afford enough food for their households [2]. Nearly every state has had significant increases in unemployment [3]. Concerns about the ability to pay rent or mortgage reached unprecedented levels [4]. Measures to protect population health have also shown adverse impacts on health behaviors, including global changes in lifestyle behaviors that reduced physical activity at all intensity levels, increased sitting time and unhealthy food consumption during social distancing due to COVID-19 [5], In the US, significant increases in alcohol consumption and weight gain were reported [6].

Unmet social risk factors like lack of access to health insurance, food insecurity, and housing instability create barriers to managing diabetes and are major drivers of poor glycemic control [7]. Prior to the pandemic, these risk factors drove much of the inequities observed in diabetes morbidity and mortality across sociodemographic groups in the US [[7], [8], [9]]. Unmet basic needs are highly prevalent, even among patients who are insured, and are associated with poor diabetes-related clinical outcomes [8,8,9].

Although data are scarce, the pandemic may have substantially exacerbated barriers to diabetes control. One study in India found that people with diabetes had significantly greater difficulty accessing medications during the pandemic, which along with job loss was associated with worsening diabetes symptoms [10]. In South Korea, Park et al. found elevated glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels [11]. In a region in Japan, no changes in HbA1c were observed comparing cohorts of people with diabetes before and during the pandemic [12]. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social needs affecting diabetes, diabetes self-care, and outcomes in the U.S. have yet to be fully described.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether pandemic exposure was worsened unmet social and diabetes needs, self-care behaviors, and diabetes outcomes among successive cohorts of people with poor glycemic control recruited into an ongoing trial before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because pandemic impacts may affect people with diabetes differently depending on their income and gender, we examined time trends taking into account these important covariates. We hypothesized that people would experience more challenges in diabetes-related care over time, and that these trends would be more pronounced among women and people with the lowest incomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

This study is a secondary data analysis of baseline assessments of participants in a randomized controlled trial evaluating approaches to addressing unmet social risk factors among people with diabetes [13]. All study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Study sample

Potential participants meeting the following criteria were identified via the University of Michigan’s Diabetes Research Registry [14], and the health system’s electronic health record: 1) 18–75 years of age, 2) diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes with prescribed oral or injectable antihyperglycemic medication, 3) most recent (within the past 6 months) recorded HbA1c level of ≥7.5% for individuals ≤70 years and >8.0% for individuals between 70–75 years in age, 4) positive report of financial burden or cost-related non-adherence using screening questions developed and validated from prior work [15,16], and 5) access to a mobile phone. Exclusion criteria included significant cognitive impairment or active participation in another diabetes-related research study. We included people with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the study since the central questions were focused on social determinants and self-care, which are relevant to all diabetes sub-types.

Eligible and interested patients were consented prior to their baseline assessments. A total of 3282 potential participants were initially contacted, of which 624 were confirmed to be eligible. Of those, 353 (63%) consented to participate, and provided completed surveys at the time of this writing. The current study is based on 353 patients recruited between June 30, 2019 and January 31, 2021. For the current analyses, individuals provided data for only one time point.

2.3. Data collection and measures

In-person interviewer-assisted surveys were conducted by trained staff prior to March 11, 2020, the same day the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, surveys were administered over the telephone. Standard demographic characteristics and clinical data were collected via self-report.

2.3.1. Unmet social and diabetes management needs and use of resources

Unmet social needs were measured using items adapted from: the Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool, the Health Leads Social Needs Screening Toolkit, the Kaiser Permanente Your Current Life Situation Questionnaire, and the National Health Interview Survey [[17], [18], [19]]. Items assessed the presence of everyday needs over the past 12 months such as food, housing, energy/utilities, income, employment, help with medical bills, and diabetes management needs (e.g. blood glucose supplies, medications/insulin, healthy food and meals, physical activity programs, and diabetes education and counseling). “Yes" responses indicated an expressed need for resources related to diabetes management or other social risks. We also asked participants if they used any assistance program or low-cost resource that provided support for the social risks and aspects of diabetes management queried.

2.3.2. Self-care behaviors

Diabetes self-management was measured using the 10-item Diabetes Self-care Activities Scale [20] assessing the frequency of specific behaviors in the last 7 days (e.g., follow healthy diet, exercise, blood glucose testing). Patients responded using a scale of 1–7 days, and mean scores are reported.

Cost-related non-adherence (CRN) for diabetes was measured by asking participants if they engaged in any of the following behaviors during the last 12 months due to diabetes-related financial burden: took less medications, skipped medication doses, delayed or decided to not fill a prescription, and delayed or decided not to see a healthcare provider (4-point Likert scale: never – often). These behaviors were analyzed as dichotomous variables, with ‘never’ and ‘rarely’ indicating ‘no’ CRN, and ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ indicating ‘yes’ to CRN. The percentage of participants with a positive response were reported for each of the six items. We also created a summary variable indicating CRN reported for any of the six items for regression models.

2.3.3. Diabetes outcomes

HbA1c was measured with the DCA Vantage Analyzer for interviews conducted in-person [21]. For patients surveyed via telephone, HbA1c’s were collected by the A1c Now home test kit [22]. Blood pressure was measured as systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure in millimeters of mercury (e.g., 120/80 mmHg) with an automated blood pressure machine [23]. Diabetes distress was measured using the 2-item Diabetes Distress Scale [24]. A mean score of the items was categorized (<3 = no distress, 3 = moderate distress, and >3 high distress).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Our primary analytic goal was to determine whether pandemic exposure was associated with unmet social and diabetes needs, self-care behaviors, and diabetes outcomes, and how these associations differed by income and gender. Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and t-tests were used to describe difference among three successive cohorts of study enrollees: pre-pandemic (enrolled prior to March 11, 2020, n = 182), early pandemic (enrolled May 1, 2020–September 30, 2020, n = 75), and later pandemic (enrolled September 30, 2020–January 31, 2021, n = 96). Because unmet needs and resource acquisition may vary according to income, time trends were examined separately for participants with self-reported annual incomes of (<$5000–$30,000 (low); $30,001–$60,000 (medium); ≥$60,001 (high)) and between women and men.

Multivariable logistic and linear regression models were used to examine the effect of time, income, and gender adjusting for potential differences over time in years living with diabetes, age, and marital status of enrollees across time. We tested models with interaction terms for pandemic exposure x income and gender, and included significant interactions in reported in final models. Models predicting CRN, diabetes self-care behaviors, and diabetes outcomes (A1c, systolic blood pressure, and diabetes distress) were also adjusted for number of chronic conditions and number of unmet social needs. All analyses were completed using R statistical package. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

A total of 353 participants were included in the analytic sample (Table 1 ). On average, participants were 53 years of age (standard deviation or SD = 13), 58% (n = 203) were female, 32% (n = 104) reported non-white race, and 13% (n = 48) had at most a high school education. Thirty-one percent of all participants (n = 108) reported household incomes <$5000–$30,000 (low income), 30% (n = 107) $30,001–$60,000 (medium income), and 37% (n = 131) ≥$60,001 (high income). Fifty-eight percent (n = 203) reported not being in the workforce, and 97% (n = 344) reported having health insurance. Mean years living with diabetes was 18.32 (SD = 11.25), mean HbA1c was 8.4 (SD = 1.5), and mean systolic blood pressure was 130.4 (SD = 19.1). Seventy-eight percent (n = 267) reported diabetes distress, with 65% (n = 229) reporting high distress.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (n = 353).

| Total sample | Pre-outbreak | COVID-19 outbreak | COVID-19 outbreak | aP-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | May–September | October–January | ||

| (n = 353) | (n = 182) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| (n = 75) | (n = 96) | ||||

| Age (mean(SD)) | 53.2 (13.2) | 50.8 (14.2) | 56.7 (11.0) | 54.9 (12.2) | <0.01 |

| Gender | 0.21 | ||||

| Female | 203 (58%) | 101 (55%) | 40 (53%) | 62 (65%) | |

| Male | 148 (42%) | 80 (44%) | 35 (47%) | 33 (34%) | |

| Race | 0.44 | ||||

| White | 241 (68%) | 128 (70%) | 54 (72%) | 59 (61%) | |

| Black or African American | 59 (17%) | 30 (16%) | 11 (15%) | 18 (19%) | |

| Asian | 12 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Other | 6 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Multiple race | 27 (8%) | 12 (7%) | 7 (9%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.58 | ||||

| Yes | 17 (5%) | 7 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (6%) | |

| No | 332 (94%) | 174 (96%) | 69 (92%) | 89 (93%) | |

| Marital status | 0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 196 (56%) | 90 (49%) | 48 (64%) | 58 (60%) | |

| No | 156 (44%) | 92 (51%) | 27 (36%) | 37 (39%) | |

| Income | 0.64 | ||||

| Less than <$5000–$30,000 | 108 (31%) | 57 (31%) | 21 (28%) | 30 (31%) | |

| $30,001–$60,000 | 107 (30%) | 51 (28%) | 24 (32%) | 32 (33%) | |

| ≥$60,001 | 131 (37%) | 72 (40%) | 30 (40%) | 29 (30%) | |

| Education | 0.07 | ||||

| Less than high school | 5 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 43 (12%) | 19 (10%) | 5 (7%) | 19 (20%) | |

| Some college | 160 (45%) | 84 (46%) | 35 (47%) | 41 (43%) | |

| College degree | 144 (41%) | 77 (42%) | 35 (47%) | 32 (33%) | |

| Employment | 0.04 | ||||

| Employed: full-time | 112 (32%) | 70 (38%) | 16 (21%) | 26 (27%) | |

| Employed: part-time | 24 (7%) | 8 (4%) | 8 (11%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Unemployed | 12 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (7%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Not in work force | 203 (58%) | 100 (55%) | 46 (61%) | 57 (59%) | |

| Has health Insurance (% yes) | 0.04 | ||||

| Yes | 344 (97%) | 181 (99%) | 72 (96%) | 91 (95%) | |

| No | 8 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (4%) | |

| Health insurance type | 0.10 | ||||

| None | 8 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (4%) | |

| Private | 148 (42%) | 83 (46%) | 29 (39%) | 36 (38%) | |

| Medicare | 25 (7%) | 10 (5%) | 5 (7%) | 10 (10%) | |

| Medicaid | 49 (14%) | 29 (16%) | 11 (15%) | 9 (9%) | |

| Medicare + medicaid supplemental | 33 (9%) | 13 (7%) | 5 (7%) | 15 (16%) | |

| Medicare + private supplemental | 87 (25%) | 45 (25%) | 21 (28%) | 21 (22%) | |

| Military | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Years living with diabetes (mean(SD)) | 18.3 (11.2) | 20.2 (10.9) | 15.7 (10.7) | 13.3 (10.7) | <0.01 |

| HbA1c % (mean (SD) | 8.4 (1.5) | 8.7 (1.5) | 8.2 (1.6) | 8.1 (1.4) | 0.07 |

| 130.4 (19.1) | 123.3 (16.6) | 137.7 (16.4) | 138.0 (20.6) | <0.01 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mean(SD)) | 76.7 (12.7) | 72.7 (11.5) | 81.2 (11.3) | 80.8 (13.5) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes distress scale (DDS-2) | 0.35 | ||||

| No distress | 77 (22%) | 36 (20%) | 18 (24%) | 23 (24%) | |

| Moderate distress | 45 (13%) | 19 (10%) | 13 (17%) | 13 (14%) | |

| High distress | 229 (65%) | 127 (70%) | 43 (57%) | 61%) |

Pre-outbreak = before March 11, 2020; COVID-19 outbreak May–September 2020; COVID-19 outbreak October 2020–January 2021.

Fisher’s exact test or one-way ANOVA.

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics varied across the three time-periods of enrollment, with the early and later-pandemic period groups being older (p < 0.01), more likely to be married (p < 0.05), more likely to be unemployed (p < 0.05), more likely to not have health insurance (p < 0.05), and living with diabetes for fewer years (p < 0.01). Participants’ clinical characteristics also varied across the time-periods of enrollment, with later pandemic groups reporting higher systolic blood pressure (p < 0.01).

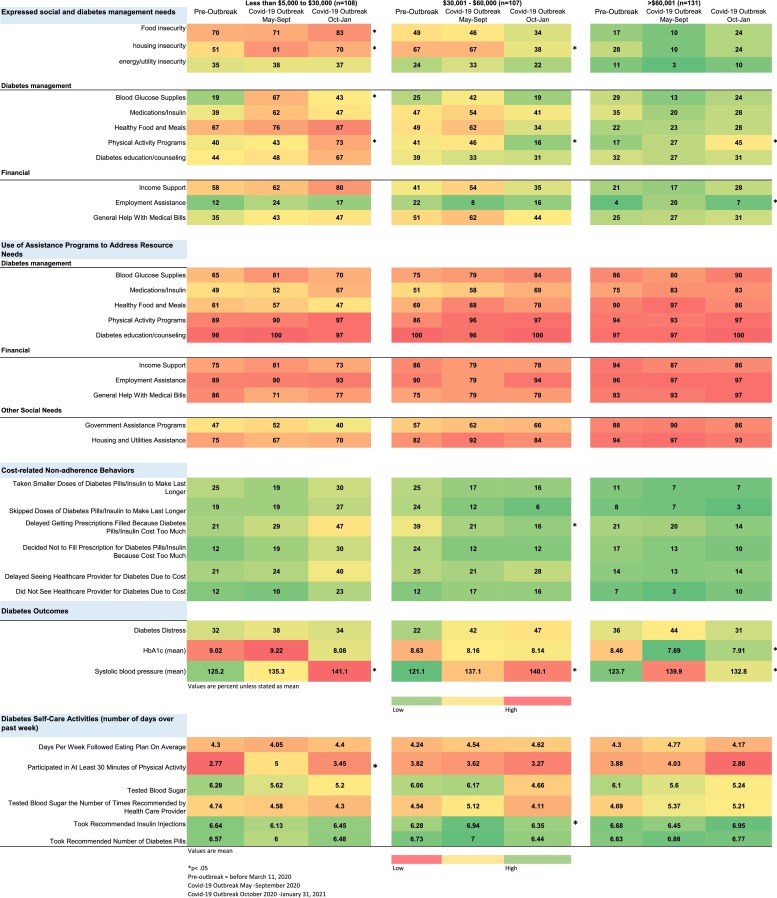

3.2. Prevalence of expressed social and diabetes needs

Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of expressed social and diabetes needs and use of assistance programs across the three time periods stratified by participant income. Among participants with low incomes, the proportion with unmet social needs increased substantially over time. Fifty-one percent of participants enrolled pre-pandemic expressed housing insecurity, compared to to 81% of participants enrolled early in the pandemic (p < 0.05). Seventy percent of participants enrolled pre-pandemic expressed food insecurity, compared to 71% of participants enrolled early in the pandemic, and 83% of participants enrolled during the later pandemic months (p < 0.05). Participants with low incomes and enrolled during the early pandemic months were more likely than similar patients enrolled pre-pandemic to express a need for income support (62% vs. 58%) and general help with medical bills (43% vs. 35%). Similar trends in housing insecurity, food insecurity, income support and general help with medical bills were observed for the middle-income group. The proportion of high-income participants with unmet social needs was generally low and stayed constant throughout the pandemic months.

Fig. 1.

Heat map of prevalence of expressed social and diabetes needs, use of assistance, self-care behaviors, and diabetes outcomes.

For the lowest income group, financial needs (income support, employment assistance, general help with medical bills) were higher during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels. In the later months of the pandemic, needs around income support were as high as 80% in the low-income group. For the high-income group, needs around employment assistance were different by 5-fold between pre-outbreak and the first part of pandemic (p < 0.05).

Participants with low income and enrolled during the early months of the pandemic in contrast to participants with similar incomes recruited pre-pandemic were more likely to express needs related to diabetes management for blood glucose supplies (67% vs. 19%, p < 0.05), medications and insulin (62% vs. 39%), and healthy food and meals (76% vs. 67%). Similar trends were observed for the middle-income group. For the higher income group, prevalence of needs around physical activity programs was significantly different across the pre-outbreak and pandemic periods (p < 0.05), with needs 10–20% higher compared to the pre-outbreak period.

3.3. Use of assistance programs

Across income groups, the general pattern was that use of assistance programs was high during the pre-pandemic period and remained high during the pandemic (Fig. 1). Among the lowest income group, need for help with accessing healthy food was higher than reported use of assistance. In general, higher income participants were more likely to report use of assistance across diabetes and social needs domains than participants with the lowest incomes. For example, during the later pandemic months, 93% of participants with high-income accessed housing and utilities assistance compared to only 70% of participants with low incomes, despite those with low-income expressing greater need (70% vs. 24%).

3.4. Association between pandemic exposure and unmet social and diabetes needs

In adjusted models, low income participants had a substantially greater odds of housing insecurity during the early pandemic months (May–Sept) compared to pre-pandemic levels (OR 20.2 [95% CI 2.8–145.2], p < 0.01) (Table 2 ). No other associations between pandemic exposure and unmet social and diabetes needs were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Association between pandemic exposure and unmet social and diabetes needs and how these associations differed by income and gender.

| Diabetes-related resources | Financial assistance | Housing insecurity | Food insecurity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | ||||

| Time | ||||

| Pre-pandemic | REFERENCE | |||

| COVID-19 (May–Sept) | 1.4 [0.7–2.8] | 1.2 [0.7–2.3] | 0.2 [0.1–1.1] | 1.0 [0.5–1.9] |

| COVID-19 (Oct–Jan) | 1.0 [0.5–2.0] | 1.3 [0.7–2.4] | 0.8 [0.2–2.3] | 1.1 [0.6–2.2] |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | REFERENCE | |||

| Female | 1.4 [0.8–2.4] | 1.7 [1.1–2.8]** | 1.7 [1.0–2.9]* | 1.3 [0.8–2.2] |

| Income | ||||

| Low | 7.0 [3.2–15.0]** | 4.2 [2.3–7.6]** | 2.4 [1.1–5.3]* | 15.1 [7.5–30.0]** |

| Middle | 2.4 [1.3–4.3]** | 2.8 [1.6–4.8]** | 5.5 [2.4–12.5]** | 4.1 [2.2–7.7]** |

| High | REFERENCE | |||

| COVID-19 (May–Sept) × low income | 20.2 [2.8–145.2]** | |||

| COVID-19 (May–Sept) × medium income | 4.0 [0.6–26.4] | |||

| COVID-19 (Oct–Jan) × low income | 3.0 [0.7–12.4] | |||

| COVID-19 (Oct–Jan) × medium income | 0.3 [0.1–1.5] | |||

Models adjusted for age, marital status, and years living with diabetes.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

3.5. Association between pandemic exposure and diabetes self-care behaviors

Across income groups, medication management was relatively high across time cohorts compared to engagement in diet and physical activity regimens (Fig. 1).

Trends in cost-related non-adherence behaviors for those with low incomes showed that problems due to cost doubled in frequency between pre-pandemic and early pandemic periods: delay filling prescriptions (47% vs. 21%), deciding not to fill a prescription (30% vs. 12%), delaying seeing a provider (40% vs. 21%), and not seeing a provider (23% vs. 12%). The opposite was observed for those with middle income, with behaviors decreasing in frequency by half: skipping doses (24% vs. 12%), deciding not to fill a prescription (24% vs. 12%), and delaying filling a prescription (39% vs. 21%).

In models adjusted for age, number of chronic conditions, marital status, years living with diabetes, and number of unmet social needs, we examined the association between pandemic exposure and frequency of diabetes self-care behaviors, and how these associations differed by income and gender. The COVID-19 pandemic was associated with more days engaging in exercise compared to pre-pandemic levels (β estimate (1.2 [95% CI 0.7–1.8], p < 0.01) (Table 3 ). No other associations between pandemic exposure and diabetes self-care behaviors were significant.

Table 3.

Association between pandemic exposure and diabetes self-care and outcomes and how these associations differed by income and gender.

| Specific diet | Exercise | Blood glucose monitoring | Medication adherence to insulin | Medication adherence to diabetes pills | Cost-related non-adherence | HbA1c | Systolic blood pressure | Diabetes distress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β estimate [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | β estimate [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | ||||||

| Time | |||||||||

| Pre-pandemic | REFERENCE | ||||||||

| COVID-19 (May–Sept) | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.6 | −0.4 | 13.3 | 0.8 |

| [−0.2 to 0.7] | [0.7–1.8]** | [−0.3 to 1.5] | [−0.4 to 0.4] | [−0.4 to 0.4] | [0.3–1.2] | [−1.0 to 0.2] | [8.4–18.2]** | [0.4–1.7] | |

| COVID-19 (Oct–Jan) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.8 | −1.1 | 15 [10.3–19.7]** | 0.81 |

| [−0.1 to 0.8] | [−0.1 to 1.0] | [−0.5 to 1.4] | [−0.2 to 0.5] | [−0.4 to 0.3] | [0.4–1.5] | [−1.8 to −0.4]** | [0.4–1.6] | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | REFERENCE | ||||||||

| Female | 0.6 | −0.5 | 0.4 | 0.12 | −0.2 | 0.9 | −0.3 | −8.0 | 1.9 |

| [0.2–1.0]** | [−0.9 to −0.04]* | [−0.2 to 1.1] | [−0.2 to 0.4] | [−0.5 to 0.1] | [0.5–1.6] | [−0.8 to 0.1] | [−12.0 to −4.1]** | [1.1–3.4]* | |

| Income | |||||||||

| Low | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.02 | −0.13 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 0.47 |

| [−0.3 to 0.6] | [−0.5 to 0.5] | [−0.5 to 0.7] | [−0.4 to 0.4] | [−0.6 to 0.3] | [0.6–2.3] | [−0.03 to 0.8] | [−2.3 to 7.9] | [0.2–1.0] | |

| Middle | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.07 | −0.15 | 0.06 | 1.7 | 0.15 | −0.2 | 0.7 |

| [−0.2 to 0.7] | [−0.6 to 0.4] | [−0.7 to 0.5] | [−0.5 to 0.2] | [−0.3 to 0.4] | [0.9–3.2] | [−0.2 to 0.5] | [−4.9 to 4.3] | [0.3–1.4] | |

| High | REFERENCE | ||||||||

Models adjusted for age, number of chronic conditions, number of unmet social needs, marital status, and years living with diabetes.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

3.6. Association between pandemic exposure and diabetes-related outcomes

Pandemic exposure during the later COVID-19 pandemic months was associated with a decrease in A1c compared to pre-pandemic levels (β = −1.1 [95% CI −1.8 to −0.4], p < 0.01). Pandemic exposure was associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure compared to pre-pandemic levels for both early pandemic (β = 13.3 [95% CI 8.4–18.2, p < 0.001) and latter pandemic months (β = 15.1 [95% CI 10.3–19.7, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

In this sample of adults with poorly controlled diabetes, already high rates of social risk factors for poor diabetes management and outcomes were exacerbated during the pandemic, particularly for patients with the lowest incomes. Although we observed no indication that A1c levels were systematically poorer as the pandemic progressed, blood pressure control deteriorated substantially. The pandemic impacted diabetes patients’ health and self-care differently depending on their incomes. Consistent with our hypothesis, people with low and middle-incomes experienced the most adverse impacts on social risk factors, particularly food and housing insecurity. Lastly, we observed high rates of assistance programs use both before and during the pandemic, however rates of service use were higher for people with higher income vs. people with low income. Our study is among the few to document the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social needs affecting diabetes, diabetes self-care, and outcomes in the U.S.

Our adjusted models did not show associations between pandemic exposure and food insecurity, perhaps because food insecurity was already very high. However, we found that people enrolled during the pandemic experienced high rates of food insecurity, housing insecurity, and needs for income support and general help with medical bills compared to pre-pandemic levels, especially for low-income groups. Our findings are consistent with recent national data demonstrating that tens of millions of people are out of work and struggling to afford adequate food and pay for rent or other housing expenses [25]. The number of people in the U.S. struggling to put food on the table has tripled since pre-pandemic levels [25]. Over 1 in 7 renters is behind on rent during the pandemic, and an estimated 9.5 million adults are in households with difficulty making mortgage payments [25]. The majority of jobs lost during the pandemic have been in industries that pay low average wages, with the lowest-paying sectors accounting for 30% of all jobs but 56% of the jobs lost from February 2020 to March 2021 [25]. The CARES Act was a major economic relief initiative passed and implemented during the earlier part of the pandemic [26]. However, the CARES Act led to long delays, confusion, and frustration for households trying to access their benefits. For example, households with low incomes and minimal savings would experience a delay in receiving their Economic Impact Payment much differently than higher-income, wealthier households in terms of benefiting from these supports and withstanding the economic shocks of the pandemic [26].

These analyses also showed varying trends in unmet social needs within and across income groups. For example, needs related to housing insecurity and income support for those with middle income were higher early in the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels, but lower during the latter part of the pandemic. Variation in unmet social needs may be due to differences in job losses across the months of the pandemic and the degree to which businesses were operating, and fluctuations in administrative capacity for government assistance such as unemployment and SNAP in assisting individuals and families in need of services [26].

Use of assistance programs was high in this sample before the pandemic, and remained high through the course of the pandemic. This may have buffered some level of economic shocks from the pandemic with people already using assistance. However, we found that the higher income group was more likely to access these programs than medium and lower income groups. For example, for the lowest income group, need across time for healthy food and meals was higher than reported use of assistance. As previously mentioned, this may have been due to confusion, delays and challenges in connecting to and accessing needed resources. Alternatively, for some individuals and families, compounding hardship may be making a bad situation worse, thus depleting bandwidth to seek out assistance.

We found that pandemic exposure was associated with more days engaging in physical activity. Increases in physical activity may be due to a heightened awareness of risk of COVID-19 complications among people with diabetes, therefore greater efforts to take care of one’s health. From the behavioral science literature, the Health Belief model supports that the expectation that increased perception of susceptibility and severity of disease can increase participation in healthy behaviors [27]. For some participants in this study, increased focus on physical activity may reflect a greater availability of time for exercise due to greater availability of time to engage in physical activity due to social distancing and stay-at-home orders. These factors may also explain our findings related to greater observed adherence to healthy eating among those with high income in the pandemic cohorts compared to pre-pandemic.

CRN behaviors for those with low incomes doubled in frequency between pre-pandemic and early pandemic cohorts, particularly with respect to delaying filling prescriptions, deciding not to fill a prescription, delaying seeing a provider, and not seeing a provider due to cost. The opposite was observed for those with middle income, with behaviors decreasing in frequency by half. For the low-income group, these trends may be explained by parallel trends of unmet needs doubling between pre-pandemic and early pandemic cohorts, particularly around blood glucose supplies, medications and insulin, and employment assistance. The opposite trend that we observed with the middle-income group may be one of managing to make diabetes self-care work within their means. However, there was an observed trend in increased diabetes distress across pandemic points, with distress doubling in prevalence from pre-pandemic to early pandemic for the middle-income group.

We saw observed decreases in A1c levels. In comparing pre-pandemic and pandemic cohorts, we observed increases in physical activity, as well as high levels of adherence to medication management for diabetes. We also observed increases in systolic blood pressure during the pandemic, and increases between pre-pandemic and pandemic cohorts, especially for low- and middle- income respondents. About two-thirds of adults with diabetes have blood pressure greater than 130/80 mm Hg or use prescription medications for hypertension [28]. High blood pressure for people with diabetes can lead to greater diabetes complications and cardiovascular events. Observed changes may be due to potentially cutting back on hypertension medicines, stress from economic shocks of the pandemic, or general pandemic stress.

There are limitations to these data that should be noted. These data represent successive, cross-sectional cohorts and do not reflect individual respondents’ trajectories over time. Data were self-report and may reflect social desirability bias. Therefore, unmet social needs and use of assistance programs may be underestimated among some study participants, but nonetheless provide indicators of where unmet needs may be elevated in this population. This study is based on surveys of patients with diabetes originally identified from a health system in one state (Michigan), therefore findings may not generalize to other states that have had different experiences with COVID-19 policies and overall economic impacts of the pandemic.

5. Conclusion

Adults with low-income and diabetes were most impacted by the pandemic in terms of unmet social and diabetes needs, especially food and housing insecurity, and challenges with blood glucose supplies. A1c levels were lower during the pandemic but systolic blood pressures were substantially higher. The economic impacts of the pandemic will be felt long after the threat of severe illness from COVID-19 decreases due to availability of vaccines. Controlled disease based on A1c may not fully capture the challenges that people with diabetes may be facing to manage their condition and may in fact make their health worse over time if whole person care is not addressed. Addressing social determinants that impact diabetes management will have to be part of standard diabetes care if we want to improve diabetes outcomes across the population.

Author contribution

M.R.P wrote the manuscript and researched data; G.Z provided statistical analysis and reviewed/edited the manuscript; C.L contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript; P.X.K.S provided statistical analysis and reviewed/edited the manuscript; R.M contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript; H.M.C Reviewed/edited the manuscript and researched data; M.H Reviewed/edited the manuscript and researched data; X.S provided statistical analysis and reviewed/edited the manuscript; K.R Reviewed/edited the manuscript and researched data; G.R Reviewed/edited the manuscript; J.P Reviewed/edited the manuscript and researched data

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK116715-01A1) and (P30DK092926) (Michigan Center for Diabetes and Translational Research). The funder had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to study staff and participants who made this work possible. Dr. Minal Patel takes full responsibility for the contents of the article. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Dorn S. Families USA; 2020. The covid-19 pandemic and resulting economic crash have caused the greatest health insurance losses in American history.https://familiesusa.org/resources/the-covid-19-pandemic-and-resulting-economic-crash-have-caused-the-greatest-health-insurance-losses-in-american-history/ Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfson J.A., Leung C.W. Food insecurity and COVID-19: disparities in early effects for US adults. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):E1648. doi: 10.3390/nu12061648. Published 2020 June 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Washington Post . 2020. Nearly every state has had record levels of unemployment last month.https://www.washingtonpost.com/ Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brookings Institute . 2020. Housing hardships reach unprecedented heights during the COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/01/housing-hardships-reach-unprecedented-heights-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammar A., Brach M., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., Bouaziz B., Bentlage E., How D., Ahmed M., Müller P., Müller N., Aloui A., Hammouda O., Paineiras-Domingos L.L., Braakman-Jansen A., Wrede C., Bastoni S., Pernambuco C.S., Mataruna L., Taheri M., Irandoust K., Khacharem A., Bragazzi N.L., Chamari K., Glenn J.M., Bott N.T., Gargouri F., Chaari L., Batatia H., Ali G.M., Abdelkarim O., Jarraya M., Abed K.E., Souissi N., Van Gemert-Pijnen L., Riemann B.L., Riemann L., Moalla W., Gómez-Raja J., Epstein M., Sanderman R., Schulz S.V., Jerg A., Al-Horani R., Mansi T., Jmail M., Barbosa F., Ferreira-Santos F., Šimunič B., Pišot R., Gaggioli A., Bailey S.J., Steinacker J.M., Driss T., Hoekelmann A. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(May (6)):1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychological Association . 2020. Stress in America- 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers E.C., McAuliff K.E., Heller C.G., Fiori K., Hollingsworth N. Toward understanding social needs among primary care patients with uncontrolled diabetes. J. Prim. Care Commun. Health. 2021;12(January–December) doi: 10.1177/2150132720985044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzpatrick S.L., Banegas M.P., Kimes T.M., Papajorgji-Taylor D., Fuoco M.J. Prevalence of unmet basic needs and association with diabetes control and care utilization among insured persons with diabetes. Popul. Health Manag. 2021;(February) doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQueen A., Kreuter M.W., Herrick C.J., Li L., Brown D.S., Haire-Joshu D. Associations among social needs, health and healthcare utilization, and desire for navigation services among US Medicaid beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2021;(March) doi: 10.1111/hsc.13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh K., Kondal D., Mohan S., Jaganathan S., Deepa M., Venkateshmurthy N.S., Jarhyan P., Anjana R.M., Narayan K.M.V., Mohan V., Tandon N., Ali M.K., Prabhakaran D., Eggleston K. Health, psychosocial, and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with chronic conditions in India: a mixed methods study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(April (1)):685. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10708-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S.D., Kim S.W., Moon J.S., Lee Y.Y., Cho N.H., Lee J.H., Jeon J.H., Choi Y.K., Kim M.K., Park K.G. Impact of social distancing due to coronavirus disease 2019 on the changes in glycosylated hemoglobin level in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2021;45(January (1)):109–114. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2020.0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe T., Temma Y., Okada J., Yamada E., Saito T., Okada K., Nakajima Y., Ozawa A., Takamizawa T., Horigome M., Okada S., Yamada M. Influence of the stage of emergency declaration due to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak on plasma glucose control of patients with diabetes mellitus in the Saku region of Japan. J. Rural Med. 2021;16(April (2)):98–101. doi: 10.2185/jrm.2020-060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel M.R., Heisler M., Piette J.D., Resnicow K., Song P.X.K., Choe H.M., Shi X., Tobi J., Smith A. Study protocol: care avenue program to improve unmet social risk factors and diabetes outcomes—a randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2020;89(February) doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.105933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan M.H., Bernstein S.J., Gendler S., Hanauer D., Herman W.H. Design, development and deployment of a Diabetes Research Registry to facilitate recruitment in clinical research. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2016;47(March):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burcu M., Alexander G.C., Ng X., et al. Construct validity and factor structure of survey-based assessment of cost-related medication burden. Med. Care. 2015;53(2):199–206. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierre-Jacques M., Safran D.G., Zhang F., Ross-Degnan D., Adams A.S., Gurwitz J., et al. Reliability of new measures of cost-related medication nonadherence. Med. Care. 2008;46(April (4)):444–448. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc59a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics . 2012. National Health Interview Survey. Public-use data file and documentation.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billoux A.K., Verlander S.A., Alley D. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2017. Standardized Screening for Health-related Social Needs in Clinical Settings: the Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Your Current Life Situation Survey . 2017. Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute Center for Population Health.www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2018/18-189-Suppl.pdf (Accessed 18 April 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toobert D.J., Hampson S.E., Glasgow R.E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(July (7)):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szymezak J., Leroy N., Lavalard E., Gillery P. Evaluation of the DCA Vantage analyzer for HbA 1c assay. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2008;46(8):1195–1198. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirst J.A., McLellan J.H., Price C.P., English E., Feakins B.G., Stevens R.J., Farmer A.J. Performance of point-of-care HbA1c test devices: implications for use in clinical practice—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017;55(February (2)):167–180. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi H., Saito K., Yakura N. Validation of Omron HEM-9200T, a home blood pressure monitoring device for the upper arm, according to the American National Standards Institute/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation/International Organization for Standardization 81060-2:2013 protocol. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021;(April) doi: 10.1038/s41371-021-00536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polonsky W.H., Fisher L., Earles J., Dudl R.J., Lees J., Mullan J., Jackson R.A. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(March (3)):626–631. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships. From: https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and (Accessed 6 May 2021).

- 26.Roll S., Grinstein-Weiss . Brookings Institute; 2020. Did the CARES Act Benefits Reach Vulnerable Americans? Evidence From a National Survey. From: https://www.brookings.edu/research/did-cares-act-benefits-reach-vulnerable-americans-evidence-from-a-national-survey/ (Accessed 6 May 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker Marshall H. Slack; Thorofare, N.J: 1974. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Diabetes Association . 2020. High Blood Pressure. From: https://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-risk/prevention/high-blood-pressure (Accessed 6 May 2021) [Google Scholar]