Abstract

Uterine isthmocele or uterine niche is a late complication of cesarean deliveries and causes chronic pelvic pain, menorrhagia or postmenstrual spotting, and infertility. As the number of cesarean sections are constantly increasing, it is important to be aware of this entity so as to make an early diagnosis. This would enable the clinicians to manage these patients efficiently. We present three patients of uterine isthmocele who were evaluated and managed at our institution.

Keywords: cesarean section, defect, isthmocele, myometrium

Introduction

Uterine isthmocele, also known as uterine niche, is a pouch-like diverticulum that forms because of myometrial thinning or defect at the site of cesarean scar in the anterior wall of the lower uterine segment. It is one of the delayed complications of cesarean section and its incidence is on the rise owing to the increase in cesarean deliveries in recent times.

It is a frequently overlooked problem in patients attending the obstetrics and gynecology clinics and its prompt recognition on ultrasound/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important as it is readily treatable. 1 Even in asymptomatic patients, it is important to be reported given the increased risk associated with gynecological procedures such as intrauterine device placement and embryo transfer. 2 3

Case 1

A 28-year-old woman presented to the pelvic imaging unit for MRI of the pelvis with a clinical diagnosis of endometriosis. She had complaints of dysmenorrhea for the past 1.5 years which had become severe for the past 3 months. Ultrasonography done elsewhere was unremarkable. Her history was unremarkable but a cesarean section which she underwent 3 years before.

MRI of the pelvis showed a fluid-filled pouch-like defect in the anterior myometrium at the site of cesarean scar. The defect measured 1.2 × 0.7 × 0.7 cm and the fluid was hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2 suggestive of blood products ( Fig. 1 ). The findings were suggestive of uterine isthmocele. There were no features of uterine adenomyosis or pelvic endometriosis. Both the ovaries were normal.

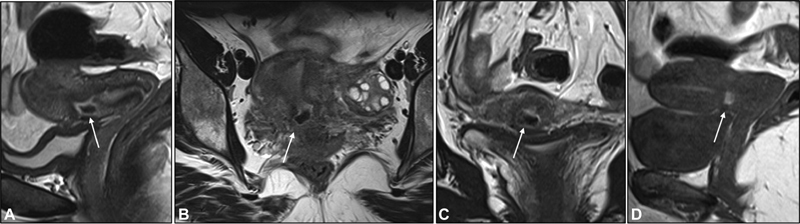

Fig. 1.

Preoperative images of case 1. T2-weighted sagittal ( A ), coronal ( B ), and axial ( C ) images and sagittal T1-weighted ( D ) MRI images of the uterus show a defect in the anterior wall in lower uterine segment with a small outpouching filled with T2 hypointense (arrows in A – C ) and T1 hyperintense contents (arrow in D ) suggestive of blood products.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy was followed by laparoscopic repair of the isthmocele. About 3 to 4 mL of blood was drained out and the defect was sutured after saline flush. Patient reported complete resolution of her symptoms after surgery. The follow-up MRI done 4 months postsurgery showed fibrosis at the site of the isthmocele with no blood products ( Fig. 2 ).

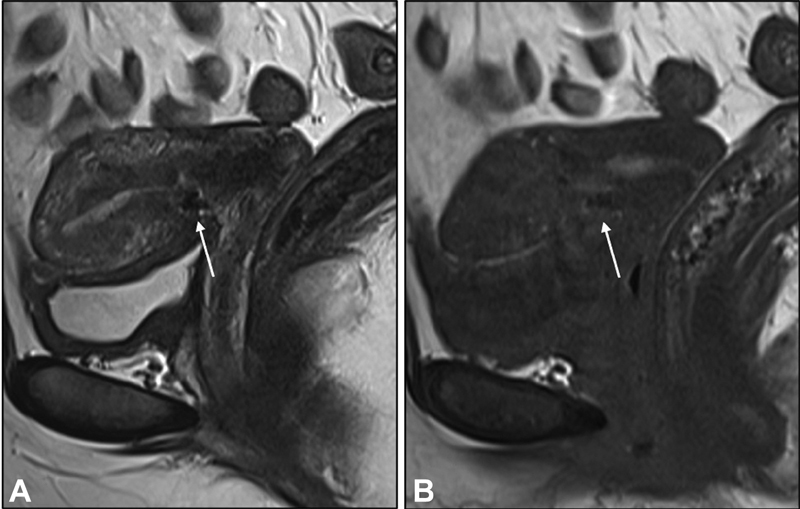

Fig. 2.

Postoperative follow-up magnetic resonance images of case 1. Sagittal T2-weighted ( A ) and T1-weighted ( B ) magnetic resonance images of the pelvis show resolution of the outpouching and the replacement of the defect with T1/T2 hypointense fibrosis (arrows).

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman with a history of postmenstrual spotting for 7 months and pelvic pain came for ultrasound of the pelvis. She had a prior history of one cesarean delivery 4 years back.

Transvaginal ultrasound showed retroflexed uterus and a large thin-walled outpouching with internal echoes in the anterior wall of the lower uterine segment seen in continuity with the endometrial cavity ( Fig. 3A ). Bilateral ovaries were normal. MRI was done prior to the surgery for exact characterization and defect measurement.

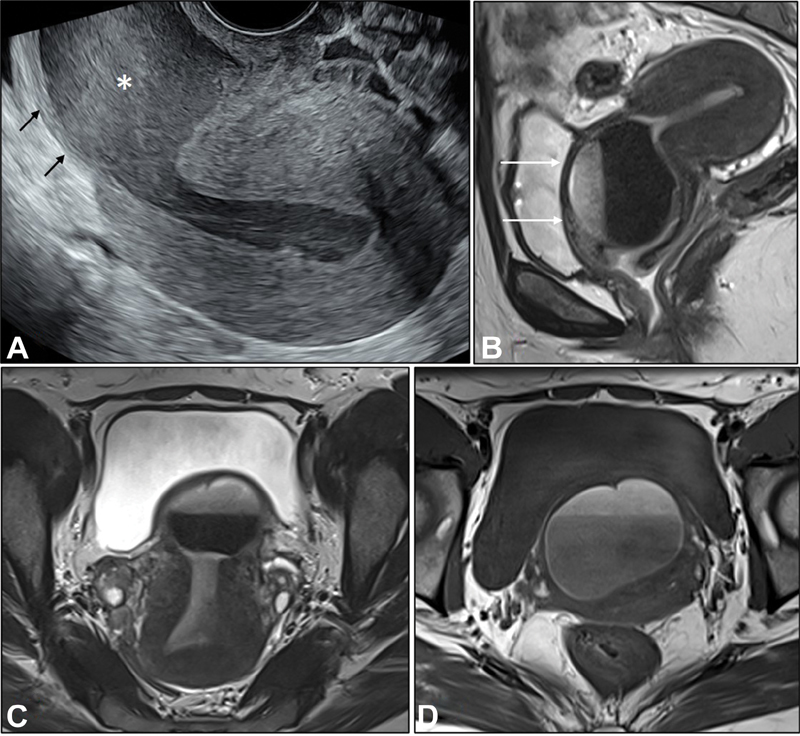

Fig. 3.

Transvaginal ultrasound image ( A ) shows a retroflexed uterus with myometrial defect in the isthmus (arrows) and an outpouching filled with low-level echoes (*) and communicating with the endometrial cavity. T2-weighted sagittal ( B ), coronal ( C ), and axial T1-weighted ( D ) magnetic resonance images of the uterus show similar findings with defect extending into the anterior lip of cervix as well (arrows in B ). The contents of the pouch are of variable intensity on T1/T2-weighted images with fluid–fluid level suggesting blood products.

MRI showed a large outpouching at the site of defect in the anterior myometrium in the lower uterine segment containing blood–blood level within it. It was seen communicating with the endometrial cavity. The defect measured 4.5 × 3.0 × 2.0 cm ( Fig. 3B–D ). Rest of the structures were unremarkable.

Approximately 30 mL of blood was evacuated and the defect was repaired laparoscopically. Patient was asymptomatic at 6 months of follow-up.

Case 3

A 35-year-old woman with complaints of pelvic pain, menorrhagia with postmenstrual mild spotting was being evaluated for secondary infertility. Ultrasound of the pelvis showed a defect in the anterior uterine wall in the region of isthmus with an outpouching containing echoes ( Fig. 4A ). MRI showed a uterine niche with blood products in it ( Fig. 4B, C ). Rest of the pelvic structures were unremarkable. The defect measured 3.0 × 2.5 × 2.0 cm. The defect was repaired laparoscopically. Patient is asymptomatic now and she is yet to conceive.

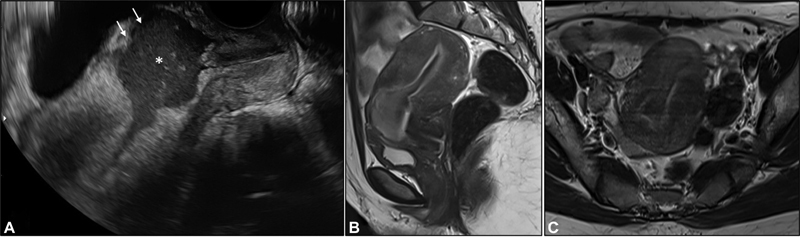

Fig. 4.

Transvaginal ultrasound image ( A ) shows a retroflexed uterus with myometrial defect in the lower uterine segment (arrows) and an outpouching filled with low-level echoes (*) and communicating with the endometrial cavity. Sagittal T2-weighted ( B ) and coronal T2-weighted ( C ) magnetic resonance images of the uterus show similar findings with varying intensity contents.

Discussion

A uterine isthmocele which is also called a uterine niche/cesarean scar defect is a defect which measures 1 to 2 mm or seen as a hypoechoic triangle in the anterior myometrium at the site of lower segment cesarian section scar. The myometrial defect will be seen communicating with the endometrial cavity. 4 5 The site of the defect can vary based on the site of the incision, stage of the labor, and the surgical technique. 6

This entity was first described by Morris in 1995 who studied a series of 51 hysterectomy specimens to define the pathological changes at the cesarean scar. 7 The defect was first laparoscopically treated by Jacobson et al in 2003. 8 The defect can be small or large. Retroflexed uterus, labor prior to the cesarean section, type of suturing technique, and the proximity to the cervix are some of the recognized risk factors for its development. 9 10 11 12

Vervoort et al proposed four different hypotheses for the development of uterine isthmocele. They are (1) incision at the lower cervix when the cervical dilatation is >5 cm, (2) incomplete surgical closure, (3) development of adhesions between the anterior abdominal wall and the site of incision, and (4) patient factors in terms of wound healing and hemostasis. 13

Isthmocele is classified as small and large, though different authors have defined different criteria for this classification. Conventionally, they are termed as “large” if the size of defect involves >50% of myometrial thickness. 9 Marotta et al classified them as large when the residual myometrial thickness at the defect was <3 mm and Tower and Frishman clinically classified them as large when they were associated with symptoms such as abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain, or infertility. 2 14

Although majority remains asymptomatic, some patients may experience postmenstrual spotting or pelvic pain owing to the collected blood within the pouch. 5 15 It may also lead to secondary infertility as the collected blood may affect the quality of cervical mucus making it hostile for the sperms. 5 The chances of scar pregnancy and uterine rupture in the subsequent pregnancies are also increased. 16

The uterine isthmocele is usually detected by transvaginal ultrasound. They are seen as an anechoic triangular defect communicating with the endometrial cavity or a subtle deformity in the anterior uterus. Sonohysterography may also be done, but it increases the size estimate of the defect due to increase in the pressure inside the uterus during the procedure. On ultrasound, the uterus may be retroflexed. The anterior myometrium in the lower uterine segment is thinned out with a defect that is covered by a thin serosa forming a pouch/niche. The pouch invariably communicates with the endometrial cavity and may contain blood products. These defects may be seen incidentally on hysterosalpingography as an outpouching of contrast at the level of isthmus, but the size measurements are not accurate. 17

MRI also shows similar findings that are best depicted on T2 images. T2-weighted images are acquired in three planes to measure the defect accurately. The width, depth, and the length of the isthmocele are measured for presurgical planning. MRI also helps rule out other pathologies that might have a causal association with the patient's presenting complaint.

It is easily identified on ultrasound and MRI may be done whenever required. Isthmocele needs to be treated in symptomatic patients and also in asymptomatic patients, if future pregnancy is planned. Minimally invasive procedures are used to close the defect which can be done through hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, or transvaginally. Studies have proven that expectant or medical management is usually unsuccessful and the first line of management of isthmocele is minimally invasive resection of the isthmocele which gives the best therapeutic results. 13 18 Smaller defects are usually treated by hysteroscopic repair, a less invasive and less morbid procedure. However, larger defects with thin myometrium require laparoscopic repair which would include resection of the isthmocele with closing of the defect in at least two layers. Combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopic repair has advantages of both which reduces the complications and achieves best repair. 14 19 20

While all our patients presented with dysmenorrhea, two had postmenstrual spotting and one had secondary infertility. All three underwent laparoscopic repair of the defect and had complete relief of the symptoms at short-term follow-up. Postoperative MRI was done in one patient after 4 months which showed T2 hypointense signal at the site of defect suggestive of fibrosis.

Conclusion

Isthmocele is a late complication of cesarean section and can have variable imaging findings from a small linear defect to a frank outpouching filled with blood products. Awareness of this condition and its imaging features is essential to make a prompt diagnosis. Surgery is the definitive treatment and is indicated in all the symptomatic and asymptomatic patients planning a pregnancy in future.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Declaration of Patient Consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

References

- 1.Jose C, Pacheco L. Isthmocele: a frequently overlooked consequence of a cesarean section scar. J Gynecol Obstet Forecast. 2018;1:1006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tower A M, Frishman G N. Cesarean scar defects: an underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(05):562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patounakis G, Ozcan M C, Chason R J. Impact of a prior cesarean delivery on embryo transfer: a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(02):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tulandi T, Cohen A. Emerging manifestations of cesarean scar defect in reproductive-aged women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(06):893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Voet L F, Bij de Vaate A M, Veersema S, Brölmann H A, Huirne J A. Long-term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: a prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG. 2014;121(02):236–244. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gubbini G, Casadio P, Marra E. Resectoscopic correction of the “isthmocele” in women with postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding and secondary infertility. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(02):172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris H. Surgical pathology of the lower uterine segment caesarean section scar: is the scar a source of clinical symptoms? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995;14(01):16–20. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson M T, Osias J, Velasco A, Charles R, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic repair of a uteroperitoneal fistula. JSLS. 2003;7(04):367–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ofili-Yebovi D, Ben-Nagi J, Sawyer E. Deficient lower-segment cesarean section scars: prevalence and risk factors. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31(01):72–77. doi: 10.1002/uog.5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C B, Chiu W W, Lee C Y, Sun Y L, Lin Y H, Tseng C J. Cesarean scar defect: correlation between cesarean section number, defect size, clinical symptoms and uterine position. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(01):85–89. doi: 10.1002/uog.6405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vikhareva Osser O, Valentin L. Risk factors for incomplete healing of the uterine incision after caesarean section. BJOG. 2010;117(09):1119–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bij de Vaate A J, van der Voet L F, Naji O. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(04):372–382. doi: 10.1002/uog.13199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vervoort A, Vissers J, Hehenkamp W, Brölmann H, Huirne J. The effect of laparoscopic resection of large niches in the uterine caesarean scar on symptoms, ultrasound findings and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2018;125(03):317–325. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marotta M L, Donnez J, Squifflet J, Jadoul P, Darii N, Donnez O. Laparoscopic repair of post-cesarean section uterine scar defects diagnosed in nonpregnant women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(03):386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bij de Vaate A J, Brölmann H A, van der Voet L F, van der Slikke J W, Veersema S, Huirne J A. Ultrasound evaluation of the cesarean scar: relation between a niche and postmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(01):93–99. doi: 10.1002/uog.8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pędraszewski P, Wlaźlak E, Panek W, Surkont G. Cesarean scar pregnancy - a new challenge for obstetricians. J Ultrason. 2018;18(72):56–62. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2018.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmadi F, Torbati L, Akhbari F, Shahrzad G. Appearance of uterine scar due to previous cesarean section on hysterosalpingography: various shapes, locations and sizes. Iran J Radiol. 2013;10(02):103–110. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tahara M, Shimizu T, Shimoura H. Preliminary report of treatment with oral contraceptive pills for intermenstrual vaginal bleeding secondary to a cesarean section scar. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(02):477–479. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abacjew-Chmylko A, Wydra D G, Olszewska H. Hysteroscopy in the treatment of uterine cesarean section scar diverticulum: a systematic review. Adv Med Sci. 2017;62(02):230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C, Tang S, Gao X. Efficacy of combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic repair of post-cesarean section uterine diverticulum: a retrospective analysis. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:1.765624E6. doi: 10.1155/2016/1765624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]