Abstract

Objectives:

To improve patient colonoscopy bowel preparation with a newly developed simplified instruction sheet in a safety-net hospital system.

Methods:

Bowel preparation quality was compared in a retrospective chart review of 543 patients, 287 of whom received standard instructions (9th grade reading level) between November 2015 and February 2016, and 256 of whom received simplified instructions (6th grade level) between March and May 2016. Instructions were mailed to all patients. The primary outcome was bowel preparation quality recorded by the endoscopist as optimal or suboptimal preparation.

Results:

543 medical records were reviewed and results indicated a significant association between the instructions used and preparation quality with patients receiving simplified instructions being significantly more prepared (69.1% vs 65.5%) and having a lower cancellation rate (4.7% vs 10.5%), p = .042.

Conclusions:

A no-cost simplified colonoscopy instruction sheet improved bowel preparation among patients in an academic safety-net health system.

Keywords: colonoscopy bowel preparation, simplified instructions, health literacy

Colonoscopy is an effective screening test for colorectal cancer (CRC) and the only test that can identify and remove polyps.1–3 This widely used tool is valuable in addressing national health objectives to increase CRC prevention and decrease CRC mortality.1,4–6

The screening effectiveness of colonsocpy is largely dependent on the endoscopist’s skill and the quality of the patient’s bowel preparation.7 Inadequate preparation is the most frequently cited cause of unsatisfactory colonoscsopy.8 Poor bowel preparation can contribute to missed adenomatous polyps (ie, pre-cancerous polyps), incomplete procedures, longer procedure times, shorter inervals between procedures, increased cost, patient inconvenience, and possible harm.7,9–11 Some studies have reported 15%−30% of patients present with poor bowel preparation with some studies reporting rates approaching 50%.12–14 Patient understanding of complex instructions is essential and a lack of adequate comprehension and ability to act on instructions is a strong predictor of suboptimal bowel preparation.15 Patient factors commonly associated with poor bowel preparation include older age, lower socioeconomic status, being Medicaid beneficiary, being male, being African-American, or having low health literacy.10–12,16–18

Understanding and adhering to multi-step, order-dependent colonoscopy instructions can be problematic for individuals with limited health literacy.16,18,19 Health literacy is defined by the Instiute of Medicine as, “an individual’s ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services they need to make appropriate health decisions.”20 Numerous studies have linked low health literacy to limited understanding of health information, lack of adherence with screening recommendations, poor medication self-management, poorer health outcomes, and increased costs.21–24 Previous studies have found patients with low health literacy are less likely to understand colonoscopy preparation instructions and lack the self-efficacy needed to properly complete screening.12,25–27 In a study of over 700 patients in a Chicago federally qualified health center, health literacy was a significant predictor of failure to understand the instructions in individuals with inadequate and marginal health literacy when compared to those with adequate health literacy.18

Most research conducted on improving quality of colonoscopy has focused on endoscopists’ training and skill, type of bowel purgative, or optimal dosing regimens; few have focused on patients.7,12,18,28 Previous studies suggest more research is needed to investigate how patient education interventions and written instructions can be more useful in improving quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy.12,18,28

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to evaluate the effectiveness of a simplified, plain language bowel preparation instruction sheet mailed to patients before a colonoscopy as compared to the standard instructions. The primary outcome was bowel preparation quality.

METHODS

Setting

The study site was at an endoscopy clinic that is part of an academic teaching hospital in northwest Louisiana that serves as one of the state’s safety-net hospitals. The hospital provides care to predominantly low socioeconomic status individuals. The clinic has 5 gastroenterologists and completes approximately 500 endoscopic procedures monthly.

Design

This study is a retrospective chart review of patients who received a routine screening or diagnostic outpatient colonoscopy (with no previous colonoscopy history) at the endoscopy clinic in a safety-net hospital between November 1, 2015 and May 31, 2016.

Original standard instruction group included patients who underwent the procedure between November 1, 2015 and February 3, 2016, using the standard bowel preparation instruction sheet. The simplified instruction group included those persons who underwent the procedure between March 1, 2016 and May 31, 2016, using the simplified preparation instruction sheet. Patients who underwent the procedure February 4–29, 2016 were excluded to avoid potential contamination due to the inability to discern which instruction sheet patients received during this period.

Patients

Inclusion criteria for medical records used in the study were English-speaking patients aged 50–75 or 45–75 for African Americans (as per American Cancer Society and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines)3,29 who received a screening or diagnostic outpatient colonoscopy at the study site by a gastroenterology fellow or faculty during the study timeframe. Exclusion criteria consisted of patients: (1) outside of the screening age; (2) presenting for surveillance colonoscopies due to personal history of CRC or colonic polyps; (3) having a medical condition known to interfere with bowel preparation which included irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, history of gastric bypass surgery, ulcerative and ischemic colitis, and colectomy; (4) who did not show up for the procedure with no documented reason; (5) in extremely poor health such as metastatic cancer patients; and (6) with incomplete procedure notes. In cases where patients had more than one colonoscopy procedure during the study period, only the first procedure was included. (The follow-up procedure was required because the first was incomplete due to suboptimal bowel preparation.)

The study was limited to screening and diagnostic outpatient colonoscopies that are the 2 most routinely preformed at this clinic. Patients with a previous history of CRC or gastrointestinal conditions or previous diagnosed polyps receiving a surveillance colonoscopy were excluded because of prior familiarity with bowel preparation, higher risk perception often associated with better quality preparation or a medical condition that interferes with their ability to prepare adequately.30

Development of Simplified Instruction Sheet

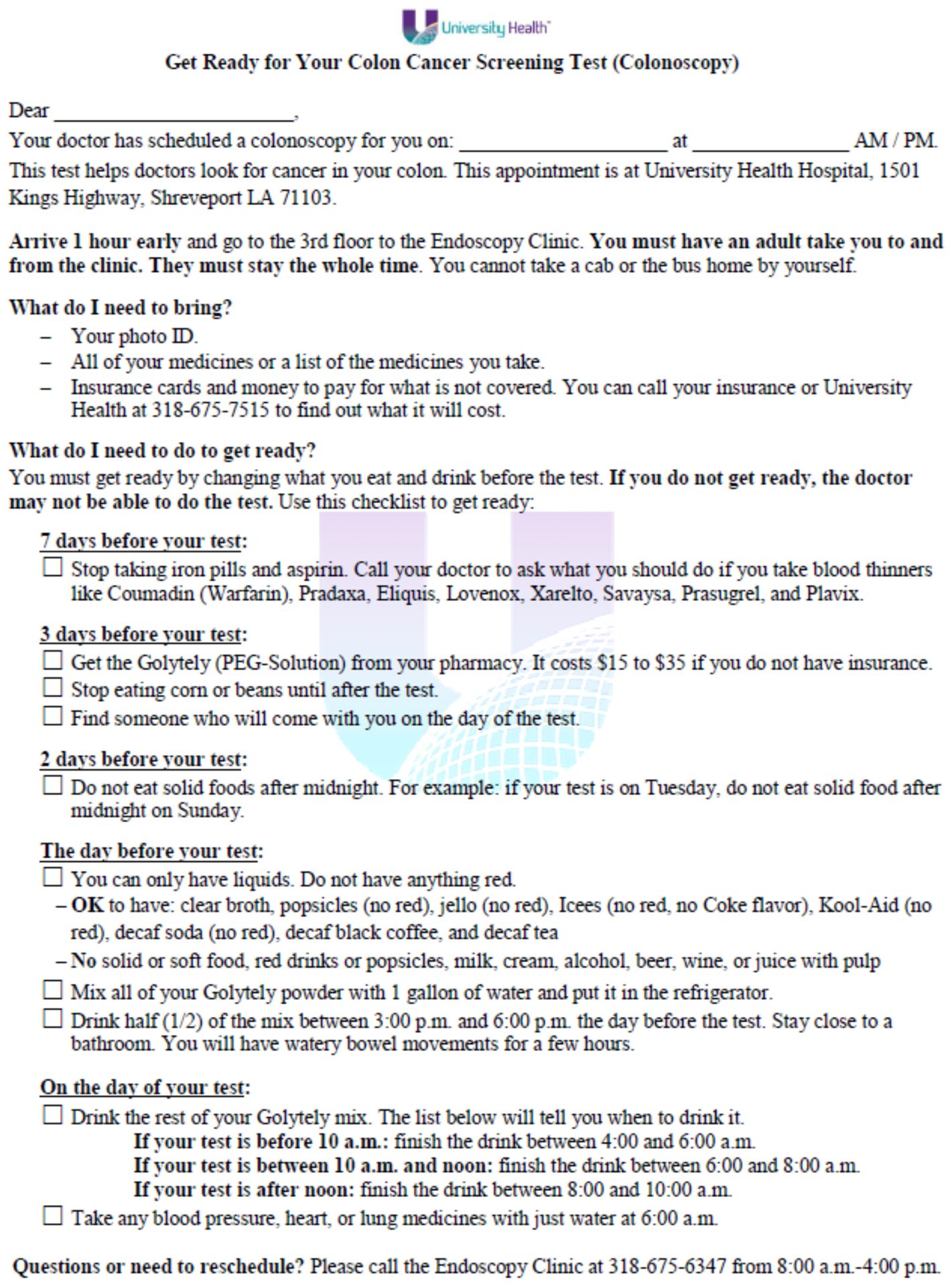

The simplified instruction sheet (Figure 1) developed by gastroenterology faculty, fellows, a nurse manager, and health services researchers used plain language principles and the guidelines from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit.31 The simplified instruction document was designed to fit on one page in a suitable format for the electronic health record (EHR) system (Figure 1). The content was arranged in chronological order and set up as a checklist that patients could follow easily, ie, follow a modified diet starting 3 days before the procedure, complete a split-dose regimen of the polyethylene glycol (PEG) electrolyte solution (bowel purgative), adjust certain medications and plan to be accompanied by an adult who will wait during the procedure and provide transportation after the procedure.

Figure 1.

Simplified Instructions

The proposed simplified instruction sheet went through multiple rounds of editing and was given to several non-medical adults of CRC screening age to read and provide feedback on for clarity. The new form was written below a 6th grade reading level (5.9) compared to the 9.6 grade level of the standardly used form as assessed using the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score. The mailed simplified instruction sheet adhered to the Department of Health and Human Services’ National Action Plan recommendation to disseminate health information that is accurate, accessible, actionable, and person-centered.32 The simplified instruction sheet was evaluated by 2 health literacy experts using the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT), a validated tool used to assess understandability and actionability of written health materials.33 The PEMAT assesses ease of comprehension with 11 items (such as material makes its purpose completely evident), layout and design (uses bullets to draw attention to keypoints) and actionability (the material breaks down any action into manageable explicit steps). The standard instructions scored a 50% on understandability and 50% on actionability; the simplified instructions scored 100% for each.

The final simplified instruction sheet was adopted by hospital administration in February 2016, and it now serves as the new standard instruction document mailed to patients who are scheduled for a colonoscopy procedure at this clinic.

The retrospective chart review was conducted through the hospital’s EHR system Epic. Eligible records were extracted using appropriate ICD-9 codes from November 2015 to May 2016 as per inclusion criteria. The specific data points requested for the report were patient medical record number (MRN), procedure date, patient age, race, sex, and health insurance status.

Outcome Measure

The data obtained from the medical records related to bowel preparation included the adequacy of preparation entered into the procedure note by the physician performing the exam or if the procedure was cancelled upon arrival at the clinic if patient indicated poor bowel prep when interviewed by intake by the nurse (eg, did not finish the bowel purgative drink, ate solid food after the cut-off time on the instructions, or whose most recent bowel movement was solid or if they arrived without another adult to provide transportation).

Adequacy of preparation was scored by gastroenterology fellows or faculty. The outcome variable was categorized as follows: (1) optimal preparation, (rated as “optimal, adequate”); (2) suboptimal preparation (rated as “suboptimal, inadequate”); (3) cancelled in pre-op due to non-adherence discovered during the check-in process at the clinic. Patients with suboptimal preparation on one side of the colon and optimal preparation on the other were considered suboptimal. The study clinic adheres to the recommendations by the United States Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer Screening: Adequate: an adequate examination is one “that allows confidence that mass lesions other than small (≤5 mm) polyps were generally not obscured by the preparation.” Inadequate: exams that “do not allow visualization of polyps 5 mm or larger.”34,35 All patients with suboptimal scores were appointed for another colonoscopy within a year.

Analysis

Preparation quality outcomes and study sample demographics characteristics between arms were compared using the independent sample t-test for age in years and Fisher’s exact test for all other categorical variables. Statistical significance is reported at the p < .05 level. The data were analyzed using SAS.36

RESULTS

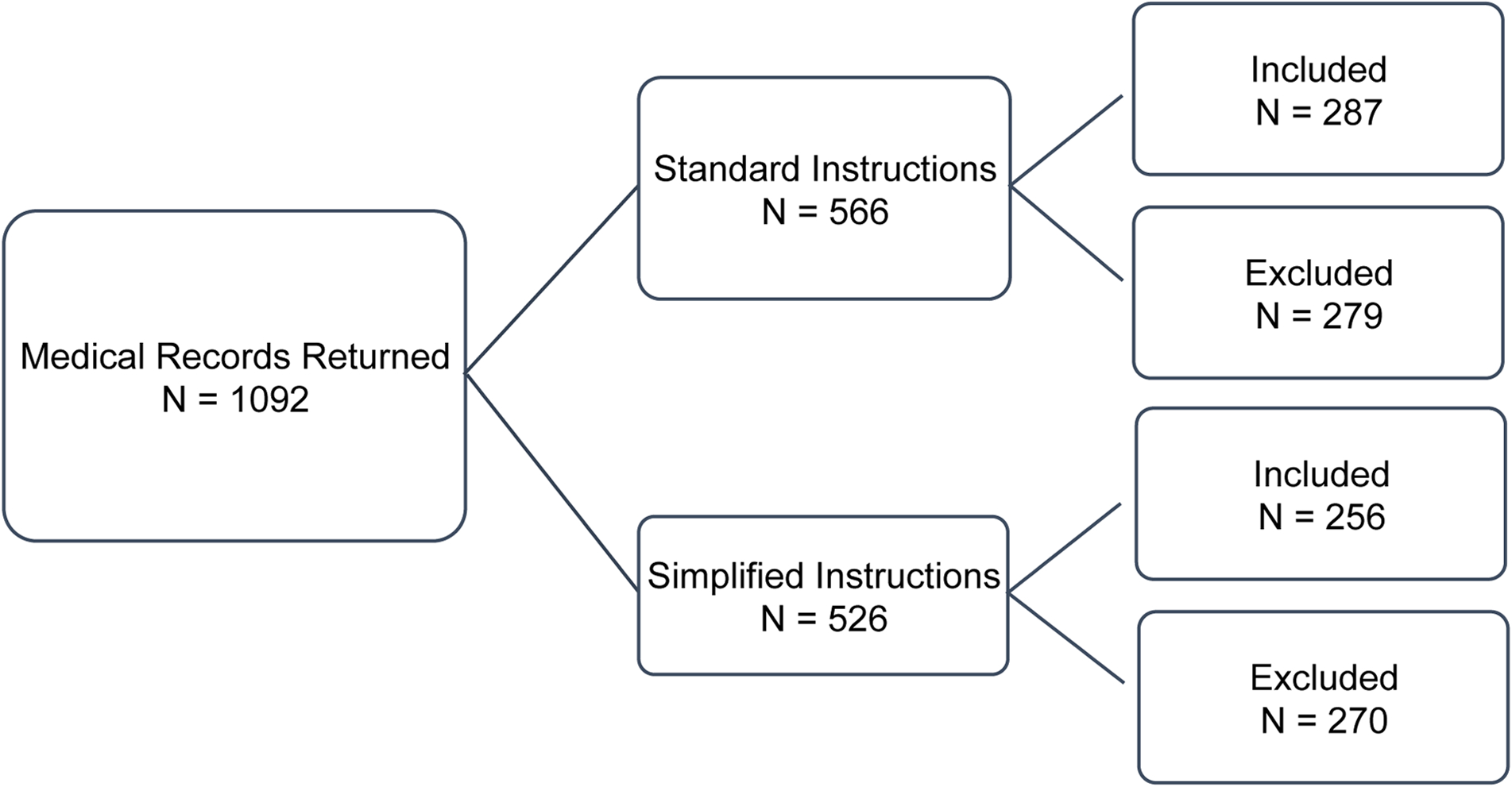

The initial report generated by the EHR included a total of 1292 medical records that matched the defined parameters (Figure 2). There was one modification to the original design to exclude records from February 4–29, 2016. The simplified preparation instructions were implemented February 3, 2016, and patients may have received the old instructions depending on when their appointment was scheduled and when their instructions were mailed. Because there was no way to verify which instructions those patients received, the data were excluded to avoid confusion. A total of 200 records were excluded as a result.

Figure 2.

Included and Excluded Medical Records

Of the 1092 records remaining, 543 were included in the final analysis (Figure 2). There were 4 exclusion categories created from the exclusion criteria. These categories were: (1) outside of the age range; (2) surveillance colonoscopies or medical conditions listed in the exclusion criteria; (3) duplicate entries for a single procedure that used more than one CPT code and patients with 2 procedures during the study timeframe or patients who were having a follow-up procedure to an initial procedure that was outside of the study timeframe; (4) patients with incomplete or unclear procedure notes. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of included and excluded medical records in each group.

Patient demographics presented in Table 1 show characteristics stratified by instruction group. Patients ranged in age from 45 to 78 with an average age of 58 years. Over half of patients were women (63.2%). Patients were predominantly low income; over 1 in 3 received free care and only 14.7% had private insurance. The majority of patients were African-American (63.9%). There was no statistically significant difference in demographic characteristics between instruction groups.

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics by Instruction Group

| Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 543) |

Original Standard Instructions (N = 287) |

Simplified Instructions (N = 256) |

p-value |

| Age, Mean (sd) | 58.27 (5.95) | 58.23 (5.97) | 58.32 (5.93) | .87 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age Categories | .86 | |||

| 45–49 | 12 (2.2) | 7 (2.4) | 5 (2.0) | |

| 50–64 | 451 (83.1) | 236 (82.2) | 215 (84.0) | |

| 65–78 | 80 (14.7) | 44 (15.3) | 36 (14.1) | |

| Sex | .48 | |||

| Female | 343 (63.2) | 177 (61.7) | 166 (64.8) | |

| Male | 200 (36.8) | 110 (38.3) | 90 (35.2) | |

| Health Insurance Status | .30 | |||

| Free Care | 186 (34.3) | 105 (36.6) | 81 (31.6) | |

| Medicaid | 118 (21.7) | 65 (22.6) | 53 (20.7) | |

| Medicare | 128 (23.6) | 69 (24) | 59 (23.1) | |

| Commercial | 80 (14.7) | 36 (12.5) | 44 (17.2) | |

| Self-pay | 27 (5.0) | 10 (3.5) | 17 (6.6) | |

| Other | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Race | .53 | |||

| African-American | 347 (63.9) | 188 (65.5) | 159 (62.1) | |

| White | 181 (33.3) | 90 (31.4) | 91 (35.6) | |

| Other | 15 (2.8) | 9 (3.1) | 6 (2.2) | |

Table 2 shows a comparison of preparation quality between groups. The results indicate a significant association between the instructions used and preparation quality with patients receiving simplified instructions being more prepared (69.1% vs 65.5%) and having a lower cancellation rate (4.7% vs 10.5%), with the combined effect of higher preparation rates and lower cancellation rates being different between the 2 groups (p = .042).

Table 2.

Comparison of Bowel Preparation Quality by Instruction Group

| Preparation Quality/Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Total N = 543 | Cancelled in Pre-Op | Suboptimal Preparation | Optimal Preparation | p-value |

| .042 | |||||

| Original Standard Instructions | 287 | 30 (10.5%) | 69 (24.0%) | 188 (65.5%) | |

| Simplified Instructions | 256 | 12 (4.7%) | 67 (26.2%) | 177 (69.1%) | |

| Total | 42 | 136 | 365 | ||

DISCUSSION

We showed that a simplified colonoscopy instruction sheet improved bowel preparation quality and decreased cancellation rates among patients in an academic safety-net health system. There was an impressive decrease in procedures cancelled at intake due to improper bowel preparation (10.5% to 4.7%). These improvements may be due to the simplified instructions being written in plain language and formatted as a checklist in chronological order. The simplified instruction sheet was designed to aid vulnerable patients most likely to struggle with commonly written instructions. The fact that it required no additional cost or staff time makes it feasible for health systems with limited resources.10,37

Several studies using more intensive and costly patient education interventions also have shown positive results. In a 2016 meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials (N = 3795), Guo et al38 reported that patients who received written instructions enhanced with pictures and cartoons were significantly more likely to have optimal bowel preparation compared to patients who received regular written instructions or verbal instructions from a healthcare provider.

Other effective interventions included educational videos, use of mobile applications or social media, and telephone education and outreach by patient navigators.38–44 A systematic review published in 2012 discussed the high cost and time investment of these interventions.45 For example, in a telephone intervention, staff members spent approximately 1–1.5 hours on each patient, and in another study case managers made almost 15,000 calls to patients during the 3-year study period.42 These intensive interventions are probably not feasible for clinics with limited resources.

Our interventon was developed to test a clinic-level no-cost intervention to improve the quality and effectiveness of screening for vulnerable patients who are more likely to have suboptimal bowel preparation.11,12,18,45 The results showed an association between the simplified instructions and improved bowel preparation, but overall findings in the literature remain mixed when testing simplified documents.46–49 Some previous studies found that simplifying the reading level of instructions alone was not effective. We were not able to identify how the simplified materials used in these studies differed from ours.

Limitations

The study has limitations. It was conducted in one healthcare system over a 7-month period. Because it is retrospective chart review, the data were limited to what is available in the medical records. Patient factors relevant to bowel preparation, such as literacy level, were unavailable in the EHR. The study clinic does not use a validated bowel preparation scale such as the Boston50 scale or the Ottawa51 scale to classify bowel preparation adequacy.

Conclusion

Suboptimal bowel preparation impacts the efficacy of colonoscopy as a CRC screening tool and places time and resource burdens on clinics that have high numbers of patients that fail to prepare adequately. Our finding that a simplified, patient-centered instruction sheet mailed to patients improved bowel preparation quality is instructional for future studies. This study is a practical example of a simple health literacy intervention to improve healthcare outcomes of vulnerable patients that required no additional cost or staff time. Future efforts could investigate the possibility of an EHR-generated 2-sided instruction sheet that would allow for larger font and increased white space to make additional improvements in reading ease. Coupling simplified instructions with patient activation strategies such as using her-generated reminder calls to prompt patients to begin preparation also should be investigated.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by 1 U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflicts are noted by the authors related to the work described.

Human Subjects Statement

The Institutional Review Board approved the quality improvement project.

References

- 1.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Colon cancer screening. 2014. Available at: www.asge.org/press/press.aspx?id=552. Accessed July 11, 2016.

- 4.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(6):1296–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider MJ. Introduction to Public Health. 2nd ed. Sud-bury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-Data?nid=4054. Accessed August 25, 2016.

- 7.Serper M, Gawron AJ, Smith SG, et al. Patient factors that affect quality of colonoscopy preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy J, Jewel Samadder N, Cox K, et al. Outcomes of next-day versus non-next-day colonoscopy after an initial inadequate bowel preparation. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(1):46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurlander JE, Sondhi AR, Waljee AK, et al. How efficacious are patient education interventions to improve bowel preparation for colonoscopy? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, et al. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1207–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dongen M Enhancing bowel preparation for colonoscopy: an integrative review. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2012;35(1):36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appannagari A, Mangla S, Liao C, et al. Risk factors for inadequate colonoscopy bowel preparations in African Americans and whites at an urban medical center. South Med J. 2014;107(4):220–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Hollander T, et al. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(6):1197–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, et al. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3 Pt 2):700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menees SB, Kim HM, Wren P, et al. Patient compliance and suboptimal bowel preparation with split-dose bowel regimen in average-risk screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(5):811–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold CL, Rademaker A, Bailey SC, et al. Literacy barriers to colorectal cancer screening in community clinics. J Health Commun. 2012;17(Suppl 3):252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parra-Blanco A, Ruiz A, Alvarez-Lobos M, et al. Achieving the best bowel preparation for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):17709–17726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith S, von Wagner C, McGregor L, et al. The influence of health literacy on comprehension of a colonoscopy preparation information leaflet. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(10):1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernon SW, Meissner HI. Evaluating approaches to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening: lessons learned from pilot studies in diverse primary care settings. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S97–S102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratzan SC. Health literacy: communication for the public good. Health Promot Int. 2001;16(2):207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller DP Jr., Brownlee CD, McCoy TP, Pignone MP. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of colorectal cancer screening: a survey study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris NS, Field TS, Wagner JL, et al. The association between health literacy and cancer-related attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. J Health Commun. 2013;18(Suppl 1):223–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tormey LK, Farraye FA, Paasche-Orlow MK. Understanding health literacy and its impact on delivering care to patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(3):745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White S, Chen J, Atchison R. Relationship of preventive health practices and health literacy: a national study. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(3):227–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson NB, Dwyer KA, Mulvaney SA, et al. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1105–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis TC, Dolan NC, Ferreira MR, et al. The role of inadequate health literacy skills in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Invest. 2001;19(2):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Wagner C, Semmler C, Good A, Wardle J. Health literacy and self-efficacy for participating in colorectal cancer screening: the role of information processing. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basch CH, Hillyer GC, Basch CE, et al. Characteristics associated with suboptimal bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy: results of a national survey. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(2):233–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2014–2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaduputi V, Chandrala C, Tariq H, et al. Influence of perception of colorectal cancer risk and patient bowel preparation behaviors: a study in minority populations. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeWalt DA, Callahan LF, Hawk VH, et al. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. (Prepared by North Carolina Network Consortium, The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, under Contract No. HHSA290200710014.) (AHRQ Publication No. 10–0046-EF) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. Development of the patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rex DK. Optimal bowel preparation-a practical guide for clinicians. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(7):419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(6):1296–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SAS Institute Inc. SAS OnlineDoc® 9.4 Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller SJ, Itzkowitz SH, Shah B, Jandorf L. Bowel prep quality in patients of low socioeconomic status undergoing screening colonoscopy with patient navigation. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(5):537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo X, Yang Z, Zhao L, et al. Enhanced instructions improve the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tae JW, Lee JC, Hong SJ, et al. Impact of patient education with cartoon visual aids on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(4):804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prakash SR, Verma S, McGowan J, et al. Improving the quality of colonoscopy bowel preparation using an educational video. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:696–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Luo H, Zhang L, et al. Telephone-based re-education on the day before colonoscopy improves the quality of bowel preparation and the polyp detection rate: a prospective, colonoscopist-blinded, randomised, controlled study. Gut. 2014;63(1):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basch CE, Wolf RL, Brouse CH, et al. Telephone outreach to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban minority population. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2246–2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calderwood AH, Mahoney EM, Jacobson BC. A plan-do-study-act approach to improving bowel preparation quality. Am J Med Qual. 2016. February 25;pii:1062860616628642. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang X, Zhao L, Leung F, et al. Delivery of instructions via mobile social media app increases quality of bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(3):429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):1033–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnold C, Rademaker A, Wolf MS, et al. Third annual fecal occult blood testing in community health clinics. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(3):302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnold C, Rademaker A, Wolf MS, et al. Final results of a 3-year literacy-informed intervention to promote annual fecal occult blood test screening. J Community Health. 2016;41(4):724–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis T, Fredrickson D, Arnold C, et al. A polio immunization pamphlet with increased appeal and simplified language does not improve comprehension to an acceptable level. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerber BS, Brodsky IG, Lawless KA, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a low-literacy diabetes education computer multimedia application. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(7):1574–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, et al. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3 Pt 2):620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]