Abstract

Objective

We aimed to systematically identify and critically assess the clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 with the AGREE II instrument.

Study design and setting

We searched Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, CNKI, CBM, WanFang, and grey literature from November 2019 – November 2020. We did not apply language restrictions. One reviewer independently screened the retrieved titles and abstracts, and a second reviewer confirmed the decisions. Full texts were assessed independently and in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. We included any guideline that provided recommendations on the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Data extraction was performed independently and in duplicate by two reviewers. We descriptively summarized CPGs characteristics. We assessed the quality with the AGREE II instrument and we summarized relevant therapeutic interventions.

Results

We retrieved 3,907 records and 71 CPGs were included. Means (Standard Deviations) of the scores for the 6 domains of the AGREE II instrument were 65%(SD19.56%), 39%(SD19.64%), 27%(SD19.48%), 70%(SD15.74%), 26%(SD18.49%), 42%(SD34.91) for the scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, editorial independence domains, respectively. Most of the CPGs showed a low overall quality (less than 40%).

Conclusion

Future CPGs for COVID-19 need to rely, for their development, on standard evidence-based methods and tools.

Abbreviations: AGREE, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; COVID-END, COVID Evidence Network to Support Decision Making; CPG, Clinical Practice Guideline; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; PRISMA, Preferred reporting items for systematic reviewsand meta-analyses; WHO, World Health Organization

Keywords: guidelines, COVID-19, rapid guidelines, quality, AGREE II tool, intensive care

What is new.

-

-

We identified and summarized the available clinical practice guidelines on the management of critical care patients with COVID-19

-

-

We highlighted the highest quality CPGs to be used, adapted or implemented in specific contexts

-

-

This is the first living systematic review of guidelines. We are continuously reviewing the available guidelines and will be publishing updates to this article when new relevant guidelines are available.

-

-

Guidelines’ developers, users, adapters, and implementers now have a comprehensive resource where they can identify the CPGs of interest and determine their quality

-

-

We have also presented a list of the most important treatments and the quality of guidelines that provide recommendations for them

Introduction

In late 2019, the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged from Wuhan, China, causing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A global ‘pandemic’ was, months later, announced by the World Health Organization (WHO)[1,2]. By February 16, 2021, a total of 108,822,960 patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 worldwide, causing the death of 2,403,641 people [3]. The COVID-19 global pandemic has spread to over 200 countries with devastating impacts on public health, patients, healthcare workers, health systems, social life, and economies. These consequences are even more evident in low- and middle-income countries [4,5].

Although most COVID-19 cases recover without any major complications, some patients develop a progressive disease due to pneumonia and respiratory failure [6].These patients are managed in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) and have high mortality rates, ranging between 25 and 40%[7].Given the extraordinary burden that the pandemic has created on the emergency and critical care units worldwide, there is an urgent need for evidence-based guidance to facilitate optimal clinical and policy decision-making.

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) are organized clinical statements designed to assist practitioners with health care decision-making and have been identified as effective tools for improving the quality of patient care by informing clinicians, and other stakeholders [8], [9], [10]. However, high-quality CPGs are methodologically complex to develop, and they are time-consuming. This makes them incompatible with emergency situations. Rapid Guidelines (RGs) are defined as CPGs which are completed in a 1- to 3-months’ timeframe are alternatives to full CPGs to provide guidance in response to an emergency [11], [12], [13]. Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic it was not surprising that a multitude of RGs were developed to inform healthcare professionals and decision-makers on the best management for patients with COVID-19. Although RGs need to follow methodological shortcuts to expedite RG development, there are key methodological elements that need to be met, even in the context of emergencies. Thus, RGs’ developers need to find an appropriate balance between rigor and speed without undermining their trustworthiness.

The Appraisal of Guidelines for REsearch and Evaluation tool (AGREE II) is the most widely utilized tool to appraise the quality of CPGs, and it has been considered as the ‘gold standard’ for CPG quality assessment [14,15]. Although, not specific for assessing RGs, AGREE II is a good blueprint of the minimum standards to consider a CPG as trustworthy.

The authors of this review, known as the ‘COVID-19 Guidelines Review Group’ (COVID-GRG), is a global group of CPG's experts and developers who aim at systematically reviewing and appraising the recently published CPGs for COVID-19. Furthermore, the COVID-GRG developed a partnership with the COVID-Evidence Network to support evidence-based decision-making (COVID-END) initiative (https://www.mcmasterforum.org/networks/covid-end) to regularly assess the quality of COVID-19 related evidence-based guidance, that can be useful for clinicians developers and stakeholders interested in finding high-quality evidence-based recommendations that will be used or adapted in their contexts.

Four previous reviews have assessed the quality of COVID-19 CPGs [16], [17], [18]. Two of them focused on the CPGs produced in the early phase of the pandemic. Zhao et al. evaluated CPGs for 5 different viruses, including SARS-CoV2, that have caused public health emergencies of international concern over 20 years, with search date ending February 2, 2020. Dagens et al. study focused on the early stage of the pandemic, with search date up to March 14, 2020 [1]. The third by Chiesa-Estomba et al. was limited to CPGs related to tracheostomies, and the fourth by Luo et al included CPGs on management of COVID-19 in pediatric wards [18].However, an assessment of all the CPGs focused on the management of critically ill COVID -19 patients was lacking. We, therefore, aimed to systematically identify the CPGs for the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19, and critically assess their quality for both clinical and methodological purposes. The clinical purpose was to inform the target users in selecting and using trustworthy CPGs in their daily practice. The methodological purpose was to inform and inspire the progress of standardization of the RG development methodologies. Considering the rapid evolution of the pandemic, the unprecedented and extraordinary volume and speed of the evidence production with COVID-19 and the need for rapid evidence synthesis and guidance, the concept of “living reviews” and “living guidance” became relevant more than ever [19]. We, therefore, considered that this project should have been framed under the same methodology to maintain a living resource that could be used by CPG users, implementers and decision-makers.

Methods

This rapid and living systematic review was informed by three methodological guides for CPGs’ systematic reviews, rapid reviews, and living reviews [8,19,20]. This review is part of a larger extensive review of all CPGs for people with COVID-19. The larger study was registered in the PROSPERO register (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020179872) [21] Our review was registered as a traditional systematic review of CPGs but given the rapid evolution of the pandemic and the speed of the evidence synthesis, we thought that a living review would have been more appropriate and useful for decision-makers and CPGs users and implementers.

Selection criteria

For inclusion, CPGs had to provide specific recommendations for clinical management, diagnosis and/or treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-19. When more than one version was available, we included only the most updated version or edition of the eligible RGs.

Bibliographic Databases and grey literature

An electronic database search was conducted from November 1, 2019 to October 1, 2020 by a health sciences librarian (LH) in Medline (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), Embase, China national knowledge infrastructure (CNKI), China Biomedical Literature database (CBM), and WanFang Data, The CPGs search filter from the CADTH database (https://www.cadth.ca/) was translated to CINAHL; and Embase to text words and relevant index terms. A search strategy was developed using the keywords that cover all the possible terms and synonyms for COVID-19 and the CPGs. Grey literature search (e.g., CPG databases and repositories and official websites of relevant critical care or intensive care professional societies as a part of snowballing) was conducted across more than 20 different resources and was extended until November 30, 2020. Search strategies are described in the (Supplementary material). No language restrictions were applied at the outset.

Selection process and data extraction

One reviewer independently screened the retrieved titles and abstracts. A second reviewer screened the undecided and included for quality control. After the first screening, 2 reviewers screened the full text independently, and a third reviewer was invited to resolve disagreements. All screening and data extraction were conducted by importing the search results into an EndNote Library (version X9) and Google Sheets. We extracted the following variables from each eligible CPG: ID (acronym or first author), country, economic classification, healthcare system, scope of the CPG, language, methods of development, date of publication, developer organization (if applicable), type of organization, target critical disease (specialty), CPG implementation tools, consideration of patients’ views and preferences, the use of specific method to assess quality of the evidence (e.g. GRADE), and all options of therapeutic interventions for critically ill people with COVID-19 whether general supportive care or specific COVID-19 therapy, results of the AGREE II quality assessments (See next section). The variables were extracted to an online Google sheet then later presented in tabular formats that were agreed upon after several online focus group discussion and brainstorming meetings with 2–4 reviewers as needed to reach final agreements.

CPGs quality assessment

Two reviewers conducted independent quality assessment of each eligible CPG with the AGREE II instrument, which consists of 23 items grouped in 6 domains, in addition to 2 final overall assessments. The six AGREE II domains are scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. The scope and purpose domain is concerned with the overall aim of the CPG, the specific health questions, and the target population; the stakeholder involvement domain focuses on the extent to which the CPG was developed by the appropriate stakeholders and represents the views of its intended users; the rigour of development domains relates to the process used to gather and synthesize the evidence, the methods to formulate the recommendations, and to update them; the clarity of presentation deals with the language, structure, and format of the CPG; the applicability domain pertains to the likely barriers and facilitators to implementation, strategies to improve uptake, and resource implications of applying the CPG; and the editorial independence domain is concerned with the formulation of recommendations not being unduly biased with competing interests.

A final overall assessment includes the rating of the overall quality of the CPG (OA1) and whether the CPG would be recommended for use in practice (OA2). Despite using only 2 appraisers meets the minimum standard for AGREE II, it potentially may reduce the reliability of results and increases the likelihood that between-rater variability may directly affect the results. The reviewers held discussions after completing the AGREE II assessments to avoid such variability or discrepancies. We used the online platform MY AGREE PLUS (https://www.agreetrust.org/my-agree/) to run the appraisals [14,15].The scoring or rating of each CPG was performed using a 7-point Likert scale and a comments section. Discrepancies in the scoring were resolved by focus group discussions facilitated by a CPG methodologist (YSA). The standardized domain score would be 0% if each appraiser scored 1 for all the items included in this domain (https://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii/) [14,15].

2.5. Data analysis

We summarized the general characteristics of the CPGs with descriptive statistics. We present frequencies and proportions to summarize categorical variables used to describe the guidelines. We used mean and standard deviation (SD) to summarize the scores across all the guidelines per domain.

The health care system classification was based on Böhm et al. [22] the economic country classification was based on the World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/country).

For defining a high quality CPG we used the AGREE II domain scores. AGREE II lacks a clear cut-off to distinguish between high- and low-quality CPGs. Several cut-offs that range from 50 to 80% have been used[23], but there is not appropriate evidence to determine that one cut-off is better than the other. We selected a cut-off for high quality CPGs of 60% or more for all the 6 AGREE II domains in consideration of the limitations associated with the RGs’ development. Moreover, the cut-offs for low and moderate quality are <40% and 40%–60%, respectively. For the overall quality of any CPG, whenever there was a discrepancy between OA1 and the mean score for all domains, we relied on the quality of the domain 3 score to upgrade or downgrade the overall score (Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, we compared the clinical content of the eligible CPGs through a tabular summary of therapeutic interventions that were mentioned in the CPGs’ recommendation.

Table 2.

Therapeutic interventions covered by the eligible rapid guidelines for critically ill people with COVID-19

|

|

|

|

a The overall quality of the included rapid guidelines (RGs) was based on a score ≥60% in D3 (AGREE II Domain 3, rigour of development, rating) per each guideline.

The table summarizes the scope of the recommendations. Each row shows the most common interventions of interest in critical patients with COVID-19 (general supportive care and therapeutic interventions). The second column displays the number of guidelines that cover each recommendation, and the following columns describes the guidelines that provide recommendations for each intervention of interest categorized as Low, Moderate or High quality according to AGREE score obtained in domain 3.

Table 3.

AGREE II Standardized Domain Scores for the 45 included rapid guidelines for critically ill patients with COVID-1923-68

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: AGREE II: Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II Instrument, Domain 1. Scope and Purpose [Items 1-3: Objectives; Health question(s); Population (patients, public, etc.)], Domain 2. Stakeholder Involvement [Items 4-6: Group Membership; Target population preferences and views; Target users], Domain 3. Rigour of development [Items 7-14: Search methods; Evidence selection criteria; Strengths and limitations of the evidence; Formulation of recommendations; Consideration of benefits and harms; Link between recommendations and evidence; External review; Updating procedure], Domain 4. Clarity and presentation [Items 15-17: Specific and unambiguous recommendations; Management options; Identifiable key recommendations]. Domain 5. Applicability [Items 18-21: Facilitators and barriers to application; Implementation advice/ tools; Resource implications; Monitoring/ auditing criteria], Domain 6. Editorial independence [Items 22, 23: Funding body; Competing interests], OA1: Overall assessment 1 (Overall quality), OA2: Overall assessment 2 (Recommend the CPG for use by the appraisers), RG: rapid guideline or guidance; N: No, Y: Yes, YWM: Yes, With Modifications.

Rapid signal for quality of RGs: Low quality: Red <40%, Moderate quality: YELLOW 40%-59%, High quality: GREEN ≥60%.

For our living systematic review approach for CPGs, the start of the regular review and update process will be launched after the publication of this first review version. We plan monthly surveillance of the databases to identify new guidelines and start the quality assessment of the included guidelines. In common agreement with the Editorial Office, we will provide regular updates, every 3 months, for at least 1 more year after the publication with new guidelines assessment.

Results

Identification of CPGs

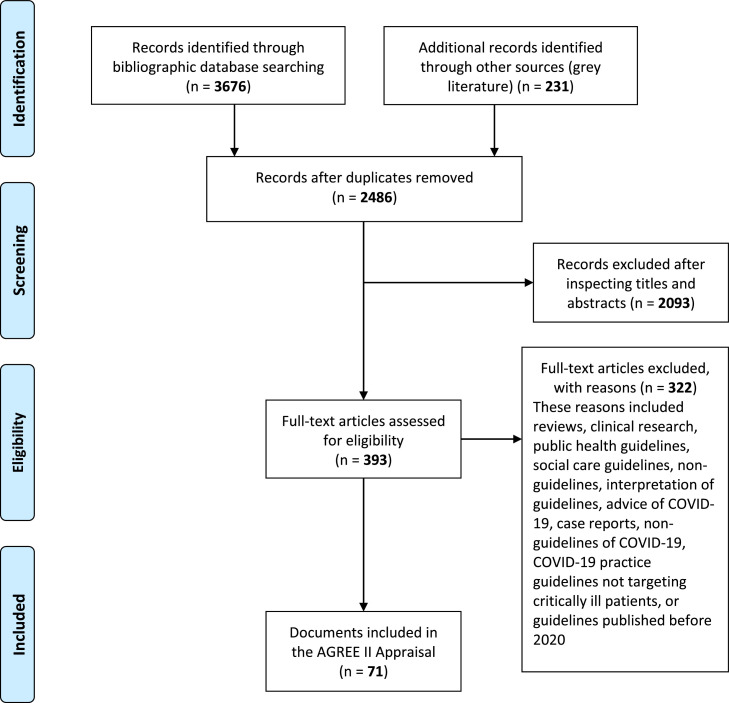

We identified 3,676 records from databases and 231 from grey literature. We screened 2,486 references and excluded, 2,093 that were not relevant, that is, they were not guidelines but other type of publications. We reviewed 393 documents in full text and excluded 322 of them with reasons. Seventy-one CPGs were included, 45 were published in English, 7 in Chinese, 7 in Italian, 5 in Spanish, 5 in German, and 2 in French [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95]. Figure 1 displays the selection process through the PRISMA statement flow diagram[21] .

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of study selection.

Characteristics of CPGs

Table 1A and Table 1B highlight the characteristics of the included CPGs. The scope of the eligible CPGs was either international (n = 18, 25%) or national (n = 53, 75%). Most of national CPGs (n = 37, 52%) were developed by high-income countries including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States, and 15 CPGs were from middle-income countries, and we did not identify CPGs from low-income countries. The included CPGs were developed by 74 specialized professional national or international organizations (or societies) in different disciplines that were mostly relevant to critical care or pulmonology. Only 30 (42%) CPGs reported their development methodology of which ten (14%) utilized a formal method for assessment of the quality of evidence. Most of the CPGs provided one or more CPG implementation tools (e.g., clinical algorithms, pathways, educational material, mobile apps, patient information guides, among others) (n = 46, 65%). Patients’ values and preferences, and resources use considerations were considered in 11 CPGs (16%).

Table 1A.

Characteristics of eligible rapid guidelines for critically ill people with COVID-19 [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95]

| RG ID | Language | Country (Economic classification) | Healthcare system of the country | Scope of RG | Methods of development | DOP (version/ edition) | Developer organization (if applicable) | Type of organization | target critical disease (specialty) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Zhao[24] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported, (Informal) Guideline Adaptation | 28/01/2020 (3) | Medical Expert Group of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) | University Hospital | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Infection Prevention/Control, Traditional Chinese Medicine) |

| 2. Zeng[25] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 01/02/2020 | Children's Hospital of Fudan University | University Hospital | Pneumonia-children (Pediatrics) |

| 3. Jin[26] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | WHO Guideline Development and the WHO Rapid Advice Guidelines Methodology, Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process as distinct from traditional de novo development (GRADE Method utilized), Expert panel consensus, systematic literature review, | 01/02/2020 | For the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University Novel Coronavirus Management and Research Team, Evidence-Based Medicine Chapter of China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Health Care (CPAM) | University Hospital | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Infection Prevention/Control, Traditional Chinese Medicine) |

| 4. NHC-SATCM-1[27] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported, (Informal) Guideline Adaptation | 14/02/2020 (2) | National Health Commission - State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (NHC-SATCM) | National/ Governmental Organization | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Infection Prevention/Control, Traditional Chinese Medicine) |

| 5. Zuo[28] | English | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 27/02/2020 | Chinese Society of Anaesthesiology | Professional Society | Pneumonia, ARDS-adults. (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology) |

| 6. NHC-SATCM-2[29] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 04/03/2020 (7) | National Health Commission - State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (NHC-SATCM) | National/ Governmental Organization | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Infection Prevention/Control, Traditional Chinese Medicine) |

| 7. ITS/AIPO/SIP[30] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 08/03/2020 | Italian Thoracic Society (ITS)/ Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists (AIPO)/ Italian Respiratory Society (SIP/IRS) | Professional Societies | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Infection Prevention/ Control |

| 8. SIMIT[31] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 13/03/2020 | Italian Society of Infectious and Tropical Diseases (SIMIT) | Professional Society | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine/ Anesthesiology/ Pulmonology) |

| 9. SIAARTI[32], [33] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 20/03/2020 | Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Intensive Care and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) | Professional Society | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine/ Anesthesiology/ Pulmonology) |

| 10. Lazzeri[34] | English | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process (as distinct from traditional de novo development), Updated Guideline, task force of experts | 25/03/2020 | Italian Association of Respiratory Physiotherapists (ARIR) in collaboration with Italian Association of Physiotherapist (AIFI) | Professional Societies | ARDS-adults (Physical therapy, Critical/ intensive care medicine) |

| 11. Alhazzani (SCCM)[35] | English | NA | NA | International | Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process as distinct from traditional de novo development (GRADE Method utilized), Expert panel consensus, systematic literature review, (Formal) Guideline Adaptation, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 28/03/2020 (updated 06/2020) |

Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC): Joint initiative of Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM)/ European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) | Professional Societies | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults and Child (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Infection Prevention/Control |

| 12. Malhorta[36] | English | India (LMIC) | PHS | National | Methods NOT reported | 28/03/2020 | Indian society of anaesthesiologists (ISA national) | Professional Society | Pneumonia, ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection Prevention/Control |

| 13. Wang[37] | English | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, literature review, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 29/03/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Pneumonia, ARDS-Adults (Nursing, Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection Prevention/Control |

| 14. He[38] | English | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Methods NOT reported | 30/03/2020 | Chinese Society of Anesthesiology | Professional Society | Anesthetic Management of Cardiac Surgical Patients (Anesthesiology/ Surgery/ Cardiac surgery/ infection control) |

| 15. Chandrasekharan[39] | English | NA | NA | International | Methods NOT reported | 30/03/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Neonatal resuscitation, Neonatal care of infants born to mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (Neonatology/ Pediatrics, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Infectious diseases) |

| 16. Yao[40] | English | NA | NA | International | Methods NOT reported | 31/03/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Endotracheal Intubation, Airway management, Pneumonia, ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Emergency Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection Prevention/Control |

| 17. Mahmud[41] | English | USA (HIC) | PHS | National | Expert panel consensus, literature review, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 01/04/2020 | Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI)/ American College of Cardiology (ACC)/ American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) | Professional Societies | Acute Myocardial Infarction (Cardiology, Emergency Medicine, Critical/ intensive care medicine) |

| 18. Thomas[42] | English | NA | NA | International | Expert panel consensus/ Methods NOT reported | 01/04/2020 | World Confederation for Physical Therapy/ International Confederation of Cardiorespiratory Physical Therapists/ Australian Physiotherapy Association/ Canadian Physiotherapy Association/ Associazione Riabilitatori dell'Insufficienza Respiratoria/ Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care (WCPT/ ICCrPt/ APTA/ CPA/ ArIR/ ACPRC) | Professional Societies | ARDS-adults (Physical therapy, Critical/ intensive care medicine, Infection Prevention/Control) |

| 19. Cook[43] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 01/04/2020 | Difficult Airway Society/ Association of Anaesthetists, Intensive Care Society/ Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists | Professional Societies | Airway management (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Emergency Medicine) |

| 20. SINPE[44] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 01/04/2020 | Italian Society For Artificial Nutrition And Metabolism (SINPE) | Professional Society | (Clinical nutrition, Critical/ intensive care medicine) |

| 21. Wang Yali[45] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Methods NOT reported | 31/03/2020 | Professional Committee of Infection and Inflammation Radiology, Chinese Research Hospital Association; Infection Imaging Professional Committee of the Radiological Branch of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Infectious Diseases Group, Radiology Branch, Chinese Medical Association Chinese Society for STD and AIDS Prevention Infection (Infectious Diseases) Imaging Working Committee; Infectious Disease Imaging Group, Infectious Diseases Branch, China Hospital Association; Infectious Diseases Group, General Radiation Equipment Professional Committee of China Equipment Association; Beijing Imaging Diagnostic and Therapeutic Technology Alliance | Professional Society | CT features of early, advanced, severe, and prognostic COVID-19 patients |

| 22. Chen[46] | Chinese | China (UMIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methodology fully reported in the RG |

20/02/2020 | Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University | University Hospital | Pneumonia, ARDS-Children (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Pediatrics, Pulmonology, Infection prevention/control) |

| 23. SINuC-SIAARTI[47] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 04/04/2020 | Italian Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (SINuC)/ Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Intensive Care and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) | Professional Society | Clinical nutrition, Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology |

| 24. PAHO/WHO[48] | Spanish | NA | NA | International | Reported using rapid systematic reviews, AGREE II instrument but no evidence or results were provided. Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process as distinct from traditional de novo development, Expert panel consensus, (Formal) Guideline Adaptation. | 06/04/2020 | Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). It also serves as the regional office for the Americas of the World Health Organization (WHO) | International public health agency | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Internal Medicine, Pulmonology, Infection prevention/control) |

| 25. Sharma[49] | English | USA (HIC) | PHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 08/04/2020 |

From: Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care (SNACC) Endorsed by: Society of Vascular & Interventional Neurology (SVIN)/ Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS)/ Neurocritical Care Society (NCS)/ European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT)/ American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS)/ Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) Cerebrovascular Section |

Professional Societies | Acute Ischemic Stroke (Critical/ intensive care medicine,, Anesthesia, Neurology, Neurosurgery) |

| 26. Miles[50] | English | USA (HIC) | PHS | National | Methods NOT reported | 08/04/2020 | New York Head and Neck Society | Professional Society | ARDS-Adults |

| 27. Flexman[51] | English | USA (HIC) | PHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 15/04/2020 | Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology & Critical Care (SNACC) | Professional Society | Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Neuro-anesthesia |

| 28. Coimbra[52] | English | NA | NA | International | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 17/04/2020 | European Society of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) | Professional Society | Emergency surgical procedures (Surgery, Emergency Medicine, Critical/ intensive care medicine) |

| 29. Matava[53] | English | Canada (HIC) | NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, literature review, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 20/04/2020 | Society for Pediatric Anesthesia's Pediatric Difficult Intubation Collaborative/ Canadian Pediatric Anesthesia Society |

Professional Societies | Pediatric airway management (Pediatrics, Emergency Medicine, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 30. Takhar[54] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, literature review, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 21/04/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Tracheostomy, airway management (Otorhinolaryngology, Emergency Medicine, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 31. Cinesi-Gómez[55] | Spanish | Spain (HIC) |

NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 01/05/2020 | Four Spanish Societies: Spanish Society of Intensive, Critical Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), Spanish Society of Emergency and Emergency Medicine (SEMES) and Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) | Professional Societies | Invasive respiratory support (Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 32. RCPCH[56] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Expert panel consensus (review of cases), Methods NOT reported | 13/05/2020 | The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) | The professional body for paediatricians in the United Kingdom (Professional Society) | Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (Pediatrics, Emergency Medicine, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 33. SA-MOH-21[57] | English | Saudi Arabia (HIC) | NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported (Informal) Guideline Adaptation |

13/05/2020 | Saudi Center for Disease Prevention and Control (Weqaya)/ Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health | National/ Governmental Organization | Airway management (Emergency Medicine, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 34. SA-MOH-22[58] | English | Saudi Arabia (HIC) | NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported (Informal) Guideline Adaptation |

13/05/2020 | Saudi Center for Disease Prevention and Control (Weqaya)/ Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health | National/ Governmental Organization | Mechanical ventilation (Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 35. Ye[59] | English | NA | NA | International | Expert panel consensus (26 members from 6 countries, majority from China and Canada, with 2 patients, 8 methodologists), literature review, Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process as distinct from traditional de novo development (GRADE Method utilized) | 19/05/2020 |

Endorsements: Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (AMMI) Canada/ Canadian Critical Care Society/ Centre for Effective Practice and the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association/ Hospital Pharmacy Professional Committee Published in Canadian Medical Association Journal & in MAGICapp. |

Professional Societies | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine) |

| 36. WHO[60] | English | NA | NA | International | Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process (as distinct from traditional de novo development), Expert panel consensus, Updated Guideline, peer review, (Informal) Guideline Adaptation, (WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd Ed, Ch. 11. Rapid advice guidelines in the setting of a public health emergency) |

27/05/2020 | World Health Organization (WHO) | Specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Internal Medicine, Pulmonology, Infection prevention/control) |

| 37. SIGN[61] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Reported Rapid Guidelines Development Process (as distinct from traditional de novo development), Expert panel consensus, Updated Guideline, peer review (Not following standard SIGN 50 development process) | 27/05/2020 | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) is part of Evidence Directorate, Healthcare Improvement Scotland/ NHS Scotland | National/ Governmental Organization | Circuit thrombosis in Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT) (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Internal Medicine, Nephrology, Infection prevention/control) |

| 38. ESC[62] | English | NA | NHS | International | Expert panel consensus, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 10/06/2020 | European Society for Cardiology (ESC) | Professional Society | Cardiovascular diseases (Cardiology, Critical/ intensive care medicine, Infection prevention/control) |

| 39. Rovira[63] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Narrative review, Expert panel consensus, Methodology fully reported in the RG | 17/06/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Tracheostomy, airway management (Otorhinolaryngology, Emergency Medicine, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 40. FICM-ICS-RCP[64] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 19/06/2020 | The Faculty of Intensive care Medicine (FICM)/ Intensive Care Society (ICS), Association of Anaesthetists (AoA), Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA), Royal College of Physicians (RCP) | Professional Societies | Thromboembolic diseases (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Internal Medicine/ Pulmonology/ Haematology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 41. FICM-ICS[65] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 22/06/2020 | The Faculty of Intensive care Medicine (FICM)/ Intensive Care Society (ICS), Association of Anaesthetists (AoA), Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) | Professional Societies | Critical care (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Internal Medicine/ Pulmonology/ Infection prevention/ control) |

| 42. Edelson[66] | English | USA (HIC) | Private Health System | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 23/06/2020 | From: Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Adult and Pediatric Task Forces of the American Heart Association In Collaboration with: American Academy of Pediatrics/ American Association for Respiratory Care, American College of Emergency Physicians/ Society of Critical Care Anesthesiologists/ American Society of Anesthesiologists |

Professional Societies | Resuscitation for children/ adults (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology/ Internal Medicine/ Emergency Medicine/ Pediatrics) |

| 43. FADOI[67] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | 23/06/2020 | The Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI) | Professional Society | Critical care (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Internal Medicine/ Pulmonology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 44. SFAR[68] | French | France (HIC) | ESHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methodology partially reported in the RG (GRADE Method utilized) | 01/07/2020 | French Society of Anesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine (SFAR) | Professional Society | Anesthesia (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Anesthesiology, Internal Medicine/ Pulmonology. Infection prevention/ control) |

| 45. Alhazzani (SCCS)[69] | English | Saudi Arabia (HIC) | NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported (Informal) Guideline Adaptation |

01/07/2020 | Saudi Critical Care Society (SCCS) | Professional Society | Pneumonia, Sepsis/septic shock/ ARDS-Adults and Child (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Laboratory Medicine, Diagnostic Radiology/ Medical Imaging, Infection Prevention/Control |

| 46. Barnes[70] | English | USA (HIC) |

Private Health System | National | Shared experiences, expert opinions, and Best practice from pre-COVID era. | 21/05/2020 | Anticoagulation Forum, a North American organization of anticoagulation providers | Professional Society | Thromboembolic diseases (Adults, Critical, high risk/ intensive care medicine, Anaesthesiology, Obstetric/ Haematology, Oncology) |

| 47. Craig[71] | English | NA | NA | International | Expert panel consensus, rely on expert opinion | 03/08/2020 | Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) working in collaboration with Safer Care Victoria and endorsed by ACEM and Safe Airway Society | Professional Society | Cardiac Arrest, Airway management for adults (Emergency Medicine/Infection prevention/ control) |

| 48. Kneyber (PEMVECC)[72] | English | NA | NA | International | Expert panel consensus, rely on expert voting * | 2020 | European Society for Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC), based on Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC) | Professional Society | Respiratory support, Pneumonia, ARDS-Paediatric (Critical/ intensive care medicine, Infection Prevention/ Control) |

| 49. Llau (SEDAR-SEMICYUC)[73] | English, Spanish | NA | NA | International | Methods NOT reported (Consensus Statement) | 04/08/2020 | Scientific Societies of Anaesthesiology-Resuscitation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) and of Intensive, Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) |

Professional Society | Thromboembolic diseases (Adults, Critical, high risk/ intensive care medicine, Anaesthesiology, Obstetric/ Haematology, Oncology, Cardiology, Neurology) |

| 50. Rochwerg[74] | English | NA | NA | International | An international panel of patients, clinicians, and methodologists produced these recommendations in adherence with standards for trustworthy guidelines using the GRADE approach, and based on a linked systematic review and network meta-analysis (GRADE Method utilized) |

30/07/2020 | MAGIC Evidence Ecosystem Foundation, BMJ Rapid Recommendations | The BMJ is working with MAGIC, a non-profit research and innovation programme, to develop Rapid Recommendations. | Pneumonia, ARDS-adults. (Critical/ Intensive care medicine, Internal Medicine, Pulmonology, Infectious diseases) |

| 51. Shekar[75] | English | NA | NA | International | Recommendations are based on available evidence, existing best practice guidelines, experience from previous infectious disease outbreaks, ethical principles, and consensus opinion from experts In addition, the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) COVID-19 Working Group Members completed a survey on patient selection criteria for ECMO to build consensus |

2020 Living document | Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) | Professional Society* | Respiratory support, Airway management, Thromboembolic diseases, Pneumonia, ARDS, Adult, Paediatrics, Neonate (Critical/ Intensive care medicine, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine, Pulmonology, Infectious diseases, Haematology, Infection prevention/ control) |

| 52. Andrejak (SPLF)[76] | French | France (HIC) | ESHI | National | Expert panel consensus, based on Delphi Methodology | 10/11/2020 | French-language Respiratory Medicine Society (SPLF) | Professional Society | respiratory sequelae after a SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Infection Control |

| 53. Nehls (DGP)[77] | German | Germany (HIC) | SHI | National | Expert panel consensus Methods not reported |

30/03/2020 |

GermanSocietyforPalliativeMedicine (DGP) withthesupportof German Society for Pneumology and Ventilatory Medicine (DGP e. V.) |

Professional Society | Palliative care, treatment for dyspnoea, use of opioids, anti-cough therapy, anxiety |

| 54. Kluge (DGIIN/DIVI)[78] | German | Germany (HIC) | SHI |

National | Literature review, Expert panel consensus Methods not reported |

24/08/2020 | GermanSocietyofInternalIntensiveCareandEmergencyMedicine (DGIIN); Berlin, GermanInterdisciplinaryAssociationforIntensiveCareandEmergencyMedicine (DIVI), Berlin | Professional Society | Diagnostics, hypoxemic failure treatment, anticoagulation, CPR, paediatric patients, antibiotic therapy |

| 55. Bajwa[79] | English | India (LMIC) | PHS | National | Methods NOT reported | 28/03/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Pneumonia, Sepsis/ septic shock/ ARDS (Critical / intensive medicine, Peri-operative care) |

| 56. Riveros[80] | Spanish |

Argentina (UMIC) |

NHS | National | Methods NOT reported |

31/12/2019 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Thromboembolism, sepsis induced coagulopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation. (Adults, intensive care medicine, Haematology, Emergency Medicine) |

| 57. Sieswerda[81] | English | Dutch | National | systemic literature review (GRADE Method utilized) |

01/10/2020 | The Guidelines Committee included members from the SWAB, the Dutch Association of Chest Physicians, the Dutch Society for Infectious Diseases, the Dutch Society for Medical Microbiology, the Dutch Society for Hospital Pharmacists, the Dutch Association of Chest Physicians, the Dutch Society of Intensive Care, and the Dutch College of General Practitioners. |

Professional Society | Hospitalized patients with a respiratory infection and Suspected or proven COVID-19. |

|

| 58. Thornton (ACTACC/SCTS)[82] | English | UK (HIC) | NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, rely on expert opinion | 4/5/2020 | Association for Cardiothoracic Anaesthesia and Critical Care (ACTACC) and the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland (SCTS). | Professional Society | Thoracic surgery Management/prevention |

| 59. Ye, Blaser[83] | English | NA | NA | International |

BMJ Rapid Recommendations. GDG: patients, clinicians, & methodologists used standards for trustworthy CPGs. Recommendations based on a linked systematic review and network meta-analysis. A weak recommendation means that both options are reasonable. (GRADE Method utilized) |

6/1/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Gastrointestinal bleeding prophylaxis, gastroenterology, Critical care |

| 60. Chekkal (SATH)[84] | English | Algeria (LMIC) | NHS | National | Summary of international CPGs with a local consensus opinion. | 3/10/2020 | Algerian society of transfusion and hemobiology (SATH) | Professional Society | Thromboprophylaxis, Hematology, critical care |

| 61. Goldenberg[85] | English | NA | NA | International | Consensus of expert opinions | 28/8/2020 | Pediatric/Neonatal Hemostasis and Thrombosis Subcommittee of the ISTH Scientific and Standardization Committee (SSC) | Affiliations of authors | Thromboprophylaxis, Hematology, critical care, Pediatrics |

| 62. Henderson (ACR)[86] | English | USA (HIC) | PHS | National | Consensus of expert opinions using a modified Delphi process | 11/2020 | American College of Rheumatology (ACR) | Professional Society | Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-C), Pediatrics, Critical Care |

| 63. Kache[87] | English | NA | NA | International | Expert opinion (Informal) Guideline Adaptation |

07/07/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Critically ill pediatric patients infected with COVID-19 (Pediatrics, Critical/ Intensive Care) |

| 64. Kakkar[88] | English | India (LMIC) |

NA |

local | Methods NOT reported | Sep/2020 | Authorship group of the article | Affiliations of authors | Acute Ischemic Stork Management/prevention |

| 65. Kranke[89] | German | Germany (HIC) | SHI |

National | Literature review, expert panel consensus Methods not reported |

09/04/2020 | UniversityHospitalof Würzburg | University Hospital | Obstetric anesthesia |

| 66. Lamb (ACCP)[90] | English | USA (HIC) | PHS | National | Consensus of expert opinions using a modified Delphi process | 05/07/2020 | American College of Chest Physicians/American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology/Association of Interventional Pulmonology Program Directors Expert Panel |

Professional Societies | Tracheostomy, critical care/ intensive care |

| 67. Martin-Delgado (SEMICYUC/ SEORL-CCC/ SEDAR)[91] | Spanish | Spain (HIC) |

NHS | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported |

11/2020 | Spanish Society of Intensive, Critical Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), the Spanish Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (SEORL-CCC) and the Spanish Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation (SEDAR) | Professional Societies | Acute respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia (Adults, intensive care medicine, Emergency Medicine, Anaesthesiology, Otorhinolaryngology) |

| 68. Neetz[92] | German | Germany (HIC) | SHI |

National | Literature review Methods not reported |

06/09/2020 | ThoracicClinicatHeidelbergUniversityHospital, PneumologyandRespulmonology, TranslationalLungResearchCenterHeidelberg (TLRC) | University Hospital/ Research center |

Airway management, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, pneumology |

| 69. Oldenburg[93] | German | Germany (HIC) | SHI |

National | Shared experiences, expert opinion Methods not reported |

01/04/2020 | German Society of Phlebology | Professional Society |

Thromboembolic diseases |

| 70. Picariello (ANMCO)[94] | Italian | Italy (HIC) | NHS, NHI | National | Expert panel consensus, Methods NOT reported | August 2020 | Italian Association of Hospital Cardiologists (ANMCO) | Professional Society | Pneumonia, Sepsis, ARDS Cardio-pulmonary disease (Critical / Intensive care medicine) |

| 71. Rimensberger (ESPNIC)[95] | English | NA | NA | International | (Informal) Guideline Adaptation | 01/2021 | European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) Scientific Sections’ Collaborative Group | Professional Societies | Septic shock, acute lung injury, acute kidney injury, Kawasaki disease (Pediatrics, Critical/ Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesiology) |

Abbreviations: DOP: Date of publication, Healthcare system classification utilized: (ESHI: Etatist Social Health Insurance, NHI: National Health Insurance, NHS: National Health Service, PHS: Private Health System, SHI: Social Health Insurance), World Bank Economic classification of countries utilized: (LMIC: Lower Middle Income Country, UMIC: Upper Middle Income Country, and HIC: High Income Country), RG: Rapid Guideline, and GRADE: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Table 1B.

Characteristics of eligible rapid guidelines for critically ill people with COVID-19 23–94

| Characteristic | N (%) Total=71 |

|---|---|

| Scope of the RG | |

| National | 50 (70%) |

| International | 19 (27%) |

| Local | 1 (1.4%) |

| Health Care System | |

| National Health Service | 15 (21%) |

| National Health Insurance | 11 (16%) |

| Social Health Insurance | 16 (23%) |

| Private Health System | 9 (13%) |

| Etatist Social Health Insurance | 2 (3%) |

| Country Economic Classification | |

| High-income | 32 (45%) |

| Upper middle income | 11 (16%) |

| Lower middle income | 3 (4%) |

| Low-income | None (0%) |

| Type of Organization | |

| University hospital | 6 (8.5%) |

| Ministry of Health/Government Department | 5 (7%) |

| Professional medical society/association | 47 (66%) |

| Other (Independent authors) | 9 (13%) |

| Independent or private organization | 4 (6%) |

| CPG Development Methods | |

| Reported | 30 (42%) |

| Not reported | 40 (56%) |

| CPG Implementation Tools(s) | |

| Yes | 46 (65%) |

| No | 24(34%) |

| Consideration of Patients’ views and Preferences | |

| Yes | 11 (16%) |

| No | 58 (82%) |

| Cost/Resources Considerations | |

| Yes | 11 (16%) |

| No | 58 (82%) |

| Use of specific method to assess quality of the evidence (e.g. GRADE) | |

| Yes | 10 (14%) |

| No | 59 (83%) |

Forty-seven CPGs were for general ICU management, 3 for patients undergoing tracheostomy, 12 about childcare, 7 about women's care, 7 about management of patients with cardiovascular diseases, 15 about management of patients with emergency conditions, 25 about management of patients with pneumonia, and 1 for patients receiving renal replacement therapy with the consideration of several overlaps in the target populations of all included CPGs (Table 1A).

Despite the fact that a number of eligible retrieved CPG documents were published as RGs, by time we observed that many of them either evolved into or were released at the outset as formal CPGs.

Methodological quality of CPGs

The AGREE II standardized domain ratings are summarized in Table 3.

Domain 1: Scope and purpose

The average AGREE II standardized score for domain 1 (scope and purpose) for the included CPGs was 65% (SD 19.56%). Scores of 43 (61%) CPGs were ≥ 60% in domain 1 [25], [26], [27] , [[31], [32], [33], 35,37,38,[40], [41], [42], [43], [44],[47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52],54,[56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61],[63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69],73,79,[81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86],90,94].

Domain 2: Stakeholder involvement

The average AGREE II standardized domain scores for domain 2 (stakeholder involvement) was 39% (SD 19.64%). Score of 10 (14%) CPGs were ≥60% in domain 2 [25,26,35,48,50,59,66,69,71,83].

Domain 3: Rigor of development

The mean score for domain 3 (rigor of development) was 27% (SD 19.48%). Scores of six CPGs were ≥60% in domain 3 [35,48,59,68,74,83]. It is worth of mentioning that 7 CPGs [24,35,59,68,74,81,83] reported the use of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Domain 4: Clarity of presentation

This domain deals with the language, structure, and format of the CPG's recommendations, comprehensiveness of the management options, and their summary. The mean score for domain 4 was 70% (SD 15.74%). Scores of 51 CPGs (72% of eligible CPGs) were ≥60% in domain 4 [24,26,28,29,[31], [32], [33],35,36,[38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45],[47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54],[56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61],[63], [64], [65], [66], [67],[69], [70], [71],73,74,77,79,[82], [83], [84], [85], [86],90,92,94].

Domain 5: Applicability

Domain 5 assesses the implementation facilitators and barriers, CPG implementation tools; cost implications, and provision of monitoring or auditing criteria. The mean score for domain 5 was 26% (SD 18.40%). Only two CPGs [43,84] scored ≥60%.

Domain 6: Editorial independence

This domain evaluates the funding body, its influence on formulating the recommendations, and other competing interests. The mean score for domain 6 was 42% (SD 34.91 %). Scores of 25 CPGs were ≥60%.[[35], [36], [37], [38],[41], [42], [43],48,49,51,53,57,59,63,69,71,74,76,79,[81], [82], [83], [84],88,95]

Overall assessment

The AGREE II standardized domain scores for the first overall assessment (OA1) had a mean of 43% (SD 20.82%). Fourteen CPGs (20%) scored greater than 60%.[26, 31,35,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51],59,60,67,68,83,84] The authors relied on the ratings of domain 3 as the basis for classification of the quality of the specific CPG (Table 2 and Table 3).

Recommending the CPGs for use in practice

The second (overall) assessment (or recommending the use of the CPG in practice) revealed a consensus agreement between the reviewers on (i) recommending the use of three (4%) CPGs [26,35,84] and (ii) another 20 (28%) to be used with modifications [24,27,29,[43], [44], [45], [46], [47],49,51,57,59,63,[65], [66], [67], [68], [69],73,76] (iii) 13 (18%) CPGs were not recommended for use by the appraisers.[28,36,37,39,52,55,64,77,80,85,86,91,93]. In the rest 35 CPGs (49%), there was no consensus between the appraisers on the final recommendation.

Summary of the therapeutic interventions included in the CPGs’ recommendations

The scope of the recommendations was variable. Regarding general supportive care, fluid therapy, vasoactive agents, supplemental oxygen therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, tracheostomy, invasive mechanical ventilation, and critical care management of pain, sedation, and delirium were addressed in 17(24%), 13(18%), 26(51%), 19(27%), 13(18%), 38(54%), and 13(18%) CPGs, respectively. Almost one third of CPGs (n = 19-21, 27–30%) addressed specific therapies such as systemic corticosteroids and antiviral agents (e.g., remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, or others). Almost a quarter of them 17 (24%) addressed empiric antimicrobials. Table 2 describes the scope of the recommendations and CPGs categorized according to their evaluated quality.

Discussion

We assessed 71 CPGs for the management of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Almost half of the CPGs were of poor methodological quality, and only 3, were of acceptable quality to recommend their use [26,35,84].Only 4 CPGs scored higher than 60% in domain 3 [35,59,68,83]. This is concerning because domain 3 defines how rigorous were methods applied, and therefore, it is a key element in defining the trustworthiness of a CPG. A possible explanation might be the extreme conditions under which these CPGs were developed including global uncertainty about the natural history of the COVID-19 infection, the lack of direct evidence, and external pressures to produce rapid advice, lack of technical capacity to develop high-quality CPGs, among others. Moreover, the continuously evolving evidence landscape of COVID-19 would require an ongoing process of monitoring and updating as some recommendations are likely to change [96]. However, even under high-pressure situations four CPGs, developed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, the French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, in addition to both CPGs by Ye et al. scored well in this domain [35,59,68,83], which shows that an CPG can be developed in a rapid timeframe maintaining the highest methodological standards. Although the AGREE II tool was developed to assess “conventional” CPGs, we consider the tool is useful to assess CPGs developed in short timeframes, which has been shown in previous publications. In the review by Kowalski et al., for instance, 46 rapid guidelines developed by WHO and NICE were assessed and obtained average scores of 71% and 81% in the rigor of development domain[10].

It has been suggested that Domains 3 (rigour of development) and 5 (applicability), in addition to domain 6 (editorial independence) may have the strongest influence on the results of the 2 overall assessments [97,98]. Some discrepancies remained after the discussions between the 23 items, the first and second overall assessments for some CPG appraisals. A limitation that was recognized earlier in a published online survey that proposed including an explicit a priori weighting of the AGREE II items and domains that should have the strongest influence on the two overall assessments [23] .

A positive sign of improvement in the CPG development methodology was the application of GRADE in some of the CPGs, unlike the CPGs appraised by Dagens et al.[1] Although GRADE requires more development and capacity, its implementation certainly improves quality and therefore, the trustworthiness. In fact, applying the highest standard methods for developing guidance is even more important in times of crisis [99,100].

Some methodological guidance has been developed to support the development of CPGs developed in a short timeframe. For instance, the evaluation of the experiences from developers of RG developed under public health emergencies [101], has been used to develop GIN-McMaster RG checklist [12]. This checklist provides practical points to consider when there is a need to develop RGs without compromising rigour [12,81]. Additional resources can also help in this endeavour, including the WHO RG development manual [102] and the Guidelines-International-Network Accelerated Guidelines Development group resources (https://g-i-n.net/working-groups/accelereated-RG-development). However, we acknowledge that further methodological research is needed to provide better guidance on RGs development.

Our work is the first 1 that focuses on only critical care CPGs. Zhao et al. reviewed the quality of CPGs of 81 CPGs, of which 30 were for COVID-19 published till February 2, 2020 [15]. Dagens et al.[1], assessed the CPGs available by March 14t, 2020, a time when there were 42 CPGs included (any COVID [15]. Chiesa-Estomba et al. appraised 17 CPGs for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients published by April 13, 2020 [16] and Luo et al. assessed 35 CPGs on management in paediatric wards facing the COVID-19 infection published by May 31, 2020 [17]. All reviews observed the overall poor quality of the majority of assessed CPGs [1,15]– [17]. Very recently, a useful resource called the COVID19 Recommendations and Gateway to Contextualization (https://covid19.recmap.org/), the RecMap, was launched [103]. The RecMap is an online open freely available evidence-based platform that provides a living map of CPGs recommendations focused on COVID19, that has been assessed with the AGREE II tool, its team is continuously updating their content. We think this might be a good resource for those interested in a full list of recommendations along with their quality assessment not only in the critical care but for other COVID-19 related fields. Our work provides a complement to this initiative for three reasons. First, we are providing updated searches and assessment of guidelines focused on 71 critical care guidelines that, until the time of this review, have not been included in the RecMap. Second, our work can inform the RecMap as we are providing a full AGREE assessment (Until the time of this review, RecMap only provides assessment of three of the six AGREE II domains for the guidelines/recommendations included). Lastly, our work is focused on the guidelines, not on the recommendations. RecMap's unit of analysis is the recommendation, while our main focus in this work has been the guideline. Users more interested in having a comprehensive view and analysis of the status of the critical care CPGs will find our work useful to decide what guidelines to use, adapt or implement. In summary, our work complements and aim to inform initiatives as RecMap and COVID-END to reduce duplication of efforts and facilitate dissemination of the guidelines’ recommendations. Therefore, our team is committed to continue collaborating with these initiatives.

We could not assess temporal changes in the quality of CPGs in comparison to the earlier recent reviews[1,16,17] due to the difference in our identified patient population, in addition to lack of the crude item and domain scores of included CPGs in those reviews. Nevertheless, Kow et al. identified multiple inconsistencies across CPGs for the management of critically ill COVID-19 patients especially in comparison with the WHO [104].

Our results will be helpful for healthcare professionals, CPG developers, CPG users/implementers, and decision-makers. Intensive care clinicians now have a summary of the available CPG and can choose among them the most trustworthy to follow. Developers and decision-makers can also choose from our list the CPGs that are of higher quality to eventually adapt or endorse a CPG to be used in their contexts.

Our work has several strengths. We conducted a comprehensive search the most important databases, and we did not apply any language restrictions. Also, we applied the most accepted tool for assessing the quality of the CPGs, the AGREE II instrument, by two experienced and trained reviewers for each CPG. Moreover, this is the first living systematic review of CPGs on COVID or on any disease. Our team is continuously monitoring the available CPGs, and we will update the CPGs’ list, and we will continuously assess the new CPGs and re-assess CPGs that may update or improve their methods. We are planning an update of our last search and new CPGs assessment in the following months and update this review version accordingly. However, this study is not free of limitations. We had to exclude, for now, CPGs that were written in languages that were not covered by our research team (i.e., Japanese). Moreover, the assessments were conducted only on CPGs that were either published in peer review journals or posted in official websites as CPG full documents, without considering unpublished or supplementary material, therefore, it is possible that some information was missing to inform the quality of the CPGs in this iteration but it is planned to be covered in the following series of this living review.

In conclusion, our living review found that most of the available CPGs developed to inform the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 are of low quality. We created a list of recommended CPGs and have described the most important topics and recommendations that they cover so this could be helpful for clinicians and decision-makers interested in the management of these patients.

Contributors

Y.S.A. led the project, overseeing the screening, data extraction, and quality assessment of CPGs, and writing the first draft of the manuscript with input from ID.F. Y.S.A. and I.D.F conceptualized the study, designed the protocol, and planned the research strategy for a series of reviews. L.H. formulated the search strategy and executed the database search. Y.S.A., M.A.T., M.W.G., A.Z., S.J.L., N.F., M.B.H., H.O., M.M.A., I.D.F., P.V.S., J.A.R., S.Z.R., P.R.J. participated in the searching, screening and data extraction, and provided comments and modifications on data analysis and interpretation. Y.S.A., M.A.T., M.W.G., H.A.W., M.M.A., M.H.H., G.M.E., M.B.H., H.Q.B., P.V.S., J.A.R., Z.F., A.Z., Z.C., S.A.A., A.A.J., S.J.L., N.F., S.A.E., S.M.A., N.U.D., M.A., R.A., S.Z.R., P.R.J participated in AGREE II assessments of eligible CPGs. Y.S.A., I.D.F., M.M.A., A.Z., Z.C., N.U.D., K.H., S.J.L., N.F., P.V.S., J.A.R., M.A., S.A.E., S.Z.R., P.R.J. participated in the tabular representation of the results. Y.S.A., I.D.F., H.A.W., M.M.A., S.J.L., N.F., J.P., S.M.A. participated in the drafting the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all included authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. Y.S.A and I.D.F. are the guarantors.

CRediT author statement

Yasser S. Amer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Maher A. Titi: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Layal Hneiny: Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Manal Mohamed Abouelkheir : Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Muddathir H. Hamad : Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Ghada Metwally ElGohary: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Mohamed Ben Hamouda: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Hella Ouertatani: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Pamela Velasquez-Salazar: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Jorge Acosta-Reyes: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Samia M. Alhabib: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Samia Ahmed Esmaeil: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Zbys Fedorowicz: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Ailing Zhang: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Zhe Chen: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Sarah Jane Lipttrott: Writing - Review & Editin, Validation. Niccolò Frungillo: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Amr A. Jamal: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Sami A. Almustanyir: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Newman Ugochukwu Dieyi: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. John Powell: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Katrina J. Hon: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation Rasmieh Alzeidan: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation. Majduldeen Azzo: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Sara Zambrano-Rico: Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Paulina Ramirez-Jaramillo Writing - Review & Editing, Validation. Ivan D. Florez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Chair for Evidence-Based Health Care and Knowledge Translation, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The funding source had no role or influence in the study design, data collection, data analysis and publication decision.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Chair for Evidence-Based Health Care and Knowledge Translation, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: None

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.11.010.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Dagens A, Sigfrid L, Cai E, Lipworth S, Cheung V, Harris E, et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020:369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [Internet]. Who.int. 2020 [cited 6 April 2020]. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

- 3.Covid19.who.int. 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [online] Available at: <https://covid19.who.int/> [Accessed 15 Feb 2021].

- 4.Bong CL, Brasher C, Chikumba E, McDougall R, Mellin-Olsen J, Enright A. The COVID-19 Pandemic: effects on low- and middle-income countries. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):86–92. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar K, Mabrouk A, Jain VK, Venkatesan A, Vaishya R. Learning opportunities from COVID-19 and future effects on health care system. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):943–946. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.036. Epub 2020 Jun 20. PMID: 32599533; PMCID: PMC7305503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.u Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quah P, Li A, Phua J. Mortality rates of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of the emerging literature. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston A, Kelly SE, Hsieh SC, Skidmore B, Wells GA. Systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines: a methodological guide. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;108:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgers J, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Clinical practice guidelines as a tool for improving patient care. Improving Patient Care. 2020:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2014. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714 [Internet]. Apps.who.int[cited 14 July 2020]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowalski SC, Morgan RL, Falavigna M, Florez ID, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Wiercioch W, et al. Development of rapid Guidelines: 1. Systematic survey of current practices and methods. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0327-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thayer KA, Schünemann HJ. Using GRADE to respond to health questions with different levels of urgency. Environ Int. 2016;92:585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan RL, Florez I, Falavigna M, Kowalski S, Akl EA, Thayer KA, et al. Development of rapid Guidelines: 3. GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist extension for rapid recommendations. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0330-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwers M., Spithoff K., Lavis J., Kho M., Makarski J., Florez ID. What to do with all the AGREEs? The AGREE portfolio of tools to support the guideline enterprise. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;125:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. J Clin Epidemol. 2010;63(12):1308–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao S, Cao J, Shi Q, Wang Z, Estill J, Lu S, et al. A quality evaluation of guidelines on five different viruses causing public health emergencies of international concern. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(7) doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiesa-Estomba CM, Lechien JR, Calvo-Henríquez C, Fakhry N, Karkos PD, Peer S, et al. Systematic review of international guidelines for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Oral Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo WY, Sun JW, Zhang WL, Li Q, Ni P, Zhao LB, et al. Management in the paediatric wards facing the novel coronavirus infection: a rapid review of Guidelines and consensuses. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, Thomas J, Higgins JP, Mavergames C, et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med. 2014;11(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE. World Health Organization; GenevaLicence: CC: 2017. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. editors. BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. No change. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amer YS, Godah MW, Titi MA, Hamad M, ElGohary GM, Wahabi HA, et al. Answering the global call for action in rapid practice guidelines for the management of people with the novel Coronavirus COVID-19: protocol for a rapid systematic review. PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020179872 Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020179872, Accessed date: December 20, 2021.

- 22.Böhm K, Schmid A, Götze R, Landwehr C, Rothgang H. Five types of OECD healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy. 2013;113(3):258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann-Eßer W, Siering U, Neugebauer EAM, Lampert U, Eikermann M. Systematic review of current guideline appraisals performed with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II instrument-a third of AGREE II users apply a cut-off for guideline quality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;95:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medical Treatment Expert Group of Tongji Hospital Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Rapid guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus infected pneumonia[J] Herald Med. 2020;39(3):305–307. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1004-0781.2020.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng M, Liu GB. Guidelines for rapid screening and clinical practice of suspected and confirmed cases of novel coronavirus infection/pneumonia in children[J] Chinese J Evid-Based Pediatr. 2020;15(01):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, Cheng H, Deng T, Fan YP, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China (NHC) Diagnosis and treatment scheme for severe and critical novel coronavirus infected pneumonia [J] Clin Educ Gen Pract. 2020;18(04):292–294. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuo MZ, Huang YG, Ma WH, et al. Expert recommendations for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with noval coronavirus disease 2019. Chinese Med Sci J. 2020;35(2):105–109. doi: 10.24920/003724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Health Commission of China (NHC) Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment scheme for novel coronavirus infected pneumonia [J] China Med. 2020;15(6):801–805. doi: 10.3760/j.issn.1673-4777.2020.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ITS/AIPO/SIP: Managing the Respiratory care of patients with COVID-19 - English version - [Internet]. Sipirs.it. 2020 [cited 23 July 2020]. Available at: http://www.sipirs.it/cms/2020/03/12/managing-the-respiratory-care-of-patients-with-covid-19-english-version/

- 31.Vademecum per la cura delle persone con malattia da COVID-19 [Internet]. Simit.org. 2020 [cited 23 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.simit.org/news/11-vademecum-per-la-cura-delle-persone-con-malattia-da-covid-19

- 32.1st ed. Rome. Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Intensive Care and Intensive Care (SIAARTI); 2020. (Percorso Assistenziale Per Il Paziente Affetto da Covid-19. Sezione 1: Procedura Area Critica [Internet]). http://www.siaarti.it/Pages/formazione-e-risorse/linee-guida.aspx, Accessed Date 1 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.1st ed. Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Intensive Care and Intensive Care (SIAARTI); Rome: 2020. Percorso Assistenziale Per Il Paziente Affetto da Covid-19. Sezione 2: Raccomandazioni Per La Gestione Locale Del Paziente Critico [Internet] Available from: http://www.siaarti.it/Pages/formazione-e-risorse/linee-guida.aspx, Accessed Date 1 July 2020. [Google Scholar]