Abstract

Background

Respiratory viruses, air pollutants, and aeroallergens are all implicated in worsening pediatric asthma symptoms, but their relative contributions to asthma exacerbations are poorly understood. A significant decrease in asthma exacerbations has been observed during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, providing a unique opportunity to study how major asthma triggers correlate with asthma activity.

Objective

To determine whether changes in respiratory viruses, air pollutants, and/or aeroallergens during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic were concomitant with decreased asthma exacerbations.

Methods

Health care utilization and respiratory viral testing data between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2020, were extracted from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Care Network’s electronic health record. Air pollution and allergen data were extracted from US Environmental Protection Agency public databases and a National Allergy Bureau–certified station, respectively. Pandemic data (2020) were compared with historical data.

Results

Recovery of in-person asthma encounters during phased reopening (June 6 to November 15, 2020) was uneven: primary care well and specialty encounters reached 94% and 74% of prepandemic levels, respectively, whereas primary care sick and hospital encounters reached 21% and 40% of prepandemic levels, respectively. During the pandemic, influenza A and influenza B decreased to negligible frequency when compared with prepandemic cases, whereas respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus infections decreased to low (though nonnegligible) prepandemic levels, as well. No changes in air pollution or aeroallergen levels relative to historical observations were noted.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that viral respiratory infections are a primary driver of pediatric asthma exacerbations. These findings have broad relevance to both clinical practice and the development of health policies aimed at reducing asthma morbidity.

Key words: Asthma, COVID-19, Respiratory virus, Pediatric to asthma, Aeroallergen, Pollution

Abbreviations used: CHOP, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; IFV-A, influenza A; IFV-B, influenza B; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

What is already known about this topic? Although respiratory viruses, air pollutants, and aeroallergens are implicated in worsening pediatric asthma symptoms, the interplay between these factors and asthma exacerbations is not well understood. Asthma exacerbations decreased significantly during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, allowing for the investigation of these asthma triggers relative to asthma activity.

What does this article add to our knowledge? The sustained reductions in viral infections and acute asthma activity we observed during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic support a strong link between respiratory virus infections and pediatric asthma exacerbations.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? Our findings suggest that viral respiratory infections are a primary driver of pediatric asthma exacerbations and that preventive measures taken to control exposure to these viruses may help limit exacerbating asthma symptoms

Introduction

Symptoms of asthma, a common pediatric respiratory disease,1 worsen with exposure to respiratory viruses, air pollution, and aeroallergens.2 In addition, patients with asthma have more frequent, severe, and longer-lasting symptoms with respiratory viral infections than do people without asthma.3 , 4 Exposure to air pollutants, including particulate pollution (particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 microns [PM2.5] and PM with diameter of less than 10 microns [PM10]), ozone, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), has been associated with increased risk of asthma development, exacerbations, and hospitalizations.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 In children with atopic asthma, aeroallergens are also a cause of asthma exacerbations.10 , 11

Public health interventions to mitigate the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative virus of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), included social distancing, mask-wearing, and quarantining of sick or exposed individuals.12, 13, 14, 15 Although it was initially suspected that asthma might be a COVID-19 risk factor—a concern that may have increased preventive health behaviors among those with asthma16 , 17—subsequent studies showed that people with asthma who contract SARS-CoV-2 were at a lower risk for adverse outcomes.18 , 19 The institution and modulation of COVID-19–related public health measures offer a unique opportunity to study their effects on health outcomes beyond those directly infected, including asthma.20 , 21 Asthma symptoms and exacerbations decreased during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic,22, 23, 24, 25 along with factors that impact asthma, such as respiratory viral infections.23 , 26, 27, 28, 29 In a previous publication, we found that during the first 2 months following public health interventions in Philadelphia, in-person asthma visits and steroid prescriptions decreased by more than 80%, with a concomitant decrease in rhinovirus infections and no change in air pollution compared with historical data for the years 2015-2019.23 Given that public health measures changed throughout 2020 and health systems resumed more in-person services, we sought to determine whether the decreased patterns of asthma activity we initially observed were maintained throughout 2020, and whether levels of respiratory viral infections, air pollution, and aeroallergens mirrored asthma activity.

Methods

Study population and timeline

Patient-level demographic characteristics of our study population are presented in Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org. We extracted asthma patient data corresponding to January 1-December 31 encounters for the years 2015 to 2020 from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Care Network, which consists of 48 outpatient primary and specialty care clinical sites, 4 urgent care sites, 15 community hospital alliances, and a 557-bed quaternary care center in the greater Delaware River Valley area; the network has maintained the same number and type of providers during this time period. Asthma diagnosis was established on the basis of encounters having International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code J45.nn. Public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in Philadelphia and surrounding counties were divided into phases. The prelockdown phase occurred from January 1 to March 17, 2020. The first lockdown occurred from March 18 to June 5, 2020, while the phased reopening consisted of an initial reopening between June 6 and June 26, 2020, and a further reopening between June 27 and November 15, 2020. The second lockdown was instituted on November 16 and lasted through January 4, 2021. A more thorough description of these time frames may be found in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org.

Variable selection

For each encounter, its type (ie, primary-well, primary-sick, specialty [Allergy and Pulmonary], emergency department [ED], inpatient, and intensive care unit) and date were extracted, along with the patient’s sex, race, ethnicity, date of birth, and payer type. Race was based on self- or parent/guardian-selection of 1 of the following categories: “white,” “Black,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” or “Other.” Subjects without a race selection were coded as “Unknown.” Asthma-related drug prescription data for all outpatient asthma-related encounters (both primary and secondary diagnosis) and inpatient asthma-related encounters (primary diagnosis only) were obtained from CHOP prescription records (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Outpatient encounters included primary-well, primary-sick, and specialty care outpatient visits, whereas hospital encounters included those in the ED, intensive care unit, or inpatient stays. Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), leukotriene modifier, and ICS + long-acting β2-agonist drugs were considered asthma maintenance medications, whereas short-acting β-agonist, systemic steroid, anticholinergic, and ED/inpatient magnesium were considered acute management medications.

Viral infection data

Results for respiratory viral testing from CHOP ED and satellite sites for adenovirus, influenza A (IFV-A), influenza B (IFV-B), metapneumovirus, non–COVID-19 coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus, parainfluenza 1, parainfluenza 2, parainfluenza 3, and COVID-19 were extracted from CHOP’s Respiratory Virus Prevalence database (see Table E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Four viruses most relevant to asthma exacerbations (IFV-A, IFV-B, RSV, and rhinovirus23 , 30), as well as COVID-19, were selected for further analysis. Data for the total weekly number of positive test results during 2020 and, separately, for 2015-2019 were obtained. Data for January 1 to March 31, 2021, were also obtained.

Air pollution data

Hourly PM2.5, PM10, ozone, and NO2 measures obtained at US Environmental Protection Agency monitoring sites in Philadelphia for the time period January 1 to December 31, 2020, were extracted from AirNow (an air quality data management system that reports real-time and forecast air quality estimates).31 Historical data from 2015 to 2019 for these pollutants were downloaded from Air Data (a US Environmental Protection Agency resource that provides quality-assured summary air pollution measures collected from outdoor regulatory monitors across the United States32). AirNow did not provide historical data for pollutants considered, and Air Data did not contain 2020 data, because its data are released months after the data are reported in AirNow. For regulatory monitors included in our study, AirNow and AirData measures were obtained at the same monitoring sites.

Aeroallergen data

Aeroallergen concentrations for trees, weed, mold, and grass pollen were measured per Burkard device guidelines at The Asthma Center, National Allergy Bureau–certified station in Mt Laurel, NJ, during the period March 17 to October 29, 2020.33 Station measures were reported as categorical variables based on historical concentrations: trees, weed, and grass pollen levels were categorized as not present, low concentration, moderate concentration, high concentration, and very high concentration for weekly average estimate ranges 0, 1 to 9, 10 to 29, 30 to 59, and 60+ particles/m3 of air, respectively; weed pollen was binned into the same levels according to weekly average ranges 0, 50 to 599, 600 to 999, 1000 to 2499, and 2500+ particles/m3 of air. Historical data for the time period 2015 to 2019 from this site were not available, but the ranges used are based on historical levels observed by the same National Allergy Bureau station that collected the 2020 data.

Data analysis

Summary statistics for rates of health care encounters and asthma-related medication prescriptions from 2020 were compared with those from 2015 to 2019. Comparisons were made between the prelockdown and the first lockdown period by comparing the average weekly encounter or medication prescription activity during the 8 weeks before and after the week of March 18, 2020. Comparisons were made between the phased-reopening time period and previous years by determining the “peak” weekly encounter or medication prescription activity, as defined as the highest 8-week moving average, between week 26 and 45 of 2020 or 2015-2019. Viral testing analysis was performed via 2 comparisons whereby summary statistics for historical data from 2015 to 2019 were compared with (1) 2020 data and (2) September 2020 to March 2021 data to cover the full influenza and RSV seasons expected for 2020-2021, which often span November to March. Weekly averages of PM2.5, PM10, ozone, and NO2 measures were calculated for the year 2020 and across the years 2015-2019. SD was calculated for historical data. Aeroallergen data were visualized according to categorical level for each week of 2020.

Data availability

The epidemiologic data supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/record/5736294).

Ethical and regulatory oversight

The CHOP Institutional Review Board reviewed our study and determined it did not meet the definition of Human Subjects research.

Results

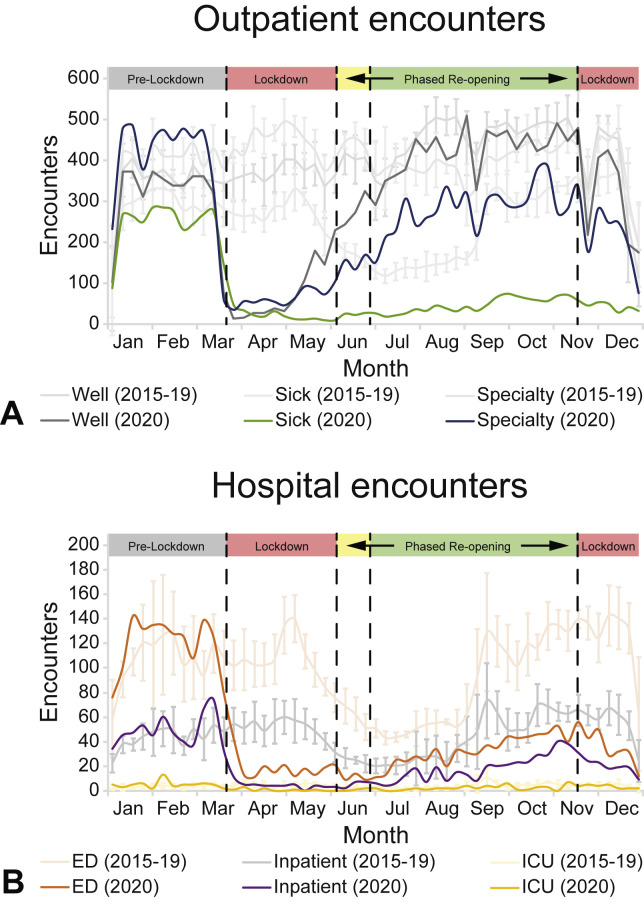

Before enacting COVID-19–related public health measures on March 18, 2020, in Philadelphia, pediatric asthma health care visit numbers and encounter types at CHOP were similar to 2015-2019 historical averages. Comparison of asthma encounters during the prelockdown to the first lockdown period showed that the average number of weekly outpatient encounters decreased to 12% of prepandemic levels (1069 encounters/wk vs 130 encounters/wk), with primary-well decreasing to 10% (351 vs 36 encounters/wk), specialty decreasing to 12% (455 vs 53 encounters/wk), and primary-sick decreasing to 16% (263 vs 41 encounters/wk) (Figure 1 , A). During this time period, the average number of weekly hospital encounters decreased to 20% of prepandemic levels (186 vs 37 encounters/wk; Figure 1, B). In the case of both outpatient and hospital encounters, weekly rates of historical data were at similar levels before and after the week of March 18.

Figure 1.

Outpatient and hospital asthma encounters during 2020. (A) Weekly averages for outpatient asthma encounters from January 1 to December 31, 2020. Primary care well visits (Well), primary care acute care visits (Sick), and specialty care visits (Specialty; Allergy and Pulmonary) are shown. (B) Weekly averages for hospital asthma encounters from January 1 to December 31, 2020. ED, inpatient admissions (Inpatient), and pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) admissions are shown. Five-year historical averages (January 1-December 31, 2015-2019) with 1 SD from the mean are shown. Phases of Philadelphia COVID-19–related public health measures are shown.

During the phased reopening June 6 to November 15, there was a gradual return of nonacute asthma-related outpatient encounters to historical and prepandemic levels. Specifically, primary-well and specialty outpatient encounters rose to 94% (456 vs 486 encounters/wk) and 74% of historical levels (317 vs 429 encounters/wk), respectively (Figure 1, A). In contrast, primary-sick encounters increased to 21% of historical levels (66 vs 319 encounters/wk; Figure 1, A), and hospital encounters increased to 40% of historical levels (75 vs 188 encounters/wk; Figure 1, B).

Before enacting COVID-19–related public health measures, pediatric asthma prescription patterns at CHOP were similar to 2015-2019 historical averages. Comparison of CHOP prescription patterns during the prelockdown to the first lockdown period found that prescriptions for each asthma maintenance (Figure 2 , A) and acute management (Figure 2, B) medication decreased relative to their prepandemic levels: ICS to 59% (436 vs 258 prescriptions/wk), ICS + long-acting β2-agonist to 70% (98 vs 68 prescriptions/wk), leukotriene modifier to 63% (122 vs 77 prescriptions/wk), short-acting β-agonist to 46% (1146 vs 530 prescriptions/wk), systemic steroids to 36% (580 vs 211 prescriptions/wk), anticholinergic to 20% (129 vs 26 prescriptions/wk), and ED/inpatient magnesium to 38% (36 vs 14 prescriptions/wk). For each of these drug classes, their levels remained similar from January to June according to historical data. We did not observe an asthma medication shortage in Philadelphia during the early stages of the pandemic.

Figure 2.

Asthma prescriptions during 2020. (A) Weekly averages for asthma maintenance medication prescriptions from January 1 to December 31, 2020. ICS, leukotriene modifiers (LTM), and ICS + long-acting β-agonist (ICS + LABA) prescriptions are shown. (B) Weekly averages for asthma acute management medication prescriptions from January 1 to December 31, 2020. Short-acting β-agonist (SABA), systemic steroid (SS), anticholinergic (AC), and magnesium (Mg) prescriptions are shown. Five-year historical averages (January 1-December 31, 2015-2019) with 1 SD from the mean are shown. Phases of Philadelphia COVID-19–related public health measures are shown.

When examining the phased reopening period, prescription patterns for all medications showed a recovery toward historical and prepandemic levels, but all remained lower through December 2020 (Figure 2). Specifically, short-acting β-agonist prescriptions were 61% of historical levels (761 vs 1240 prescriptions/wk), systemic steroid prescriptions were 58% of historical levels (338 vs 576 prescriptions/wk), anticholinergic prescriptions were 34% of historical levels (53 vs 153 prescriptions/wk), and ED/inpatient magnesium prescriptions were 66% of historical levels (23 vs 35 prescriptions/wk). In comparison, ICS prescriptions were 56% of historical levels (308 vs 551 prescriptions/wk), leukotriene modifier prescriptions were 65% of historical levels (97 vs 149 prescriptions/wk), and ICS + long-acting β2-agonist prescriptions were 84% of historical levels (85 vs 101 prescriptions/wk).

Testing for all viruses continued during 2020 though the number of non–COVID-19 tests performed decreased when compared with historical testing figures. During the prelockdown phase, an increase in the number of positive IFV-A and IFV-B test results was observed as compared with historical averages.23 In addition, both the number of positive RSV and positive rhinovirus test results decreased during this time period when compared with historical averages. Just as the first lockdown was instituted, the number of positive results for rhinovirus increased. However, this increase (as a percentage of total rhinovirus test results) was similar to the historical average (see Table E3). The weekly total positive test results for IFV-A, IFV-B, RSV, and rhinovirus during the first lockdown, phased reopening, and second lockdown were significantly lower than 2015-2019 historical averages even as the number of positive COVID-19 test results increased (Figure 3 ). When investigating seasonal trends, and focusing on months of peak viral transmission, the respiratory viral data from September 2020 to March 2021 showed that positive test results for IFV-A, IFV-B, and RSV were at or near zero when compared with their historical averages. Positive rhinovirus test results, while nonzero, also remained significantly lower than antecedent averages (Figure 4 ).

Figure 3.

Viral respiratory testing data using deidentified institutional ED and satellite sites virology testing results for the period 2015 to 2020. Time series plots comparing historical average data (dark gray lines) and ±1 SD (light gray shaded areas) from 2015 to 2019 to 2020 data (dark blue lines) for total number of weekly positive IFN-A, IFV-B, RSV, rhinovirus, and COVID-19 test results, respectively. Phases of Philadelphia COVID-19–related public health measures are shown.

Figure 4.

Viral respiratory testing data comparing September 2020 to March 2021 to historical data (2015-2019). Total number of weekly positive IFV-A, IFV-B, RSV, rhinovirus, and COVID-19 testing data (dark blue lines with blue markers) from the ED and satellite sites are compared with the 2015-2019 historical average (dark gray lines) ±SD (light gray shaded areas) during the same period. Weeks during which tests were not performed are without markers.

Air pollution and aeroallergen trends did not substantially change during the pandemic compared with historical or expected seasonal data,11 , 28 respectively (Figure 5 ). Although seasonal variability in daily average PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and ozone was observed, the variability was similar to historical trends across the years 2015-2019. Aeroallergen concentrations during most weeks of 2020 were not present or low concentration, with high concentration of weed pollen in September, very high concentration of tree pollen in March-May, high concentration to very high concentration of mold pollen in mid-March-October, and moderate concentration of grass pollen in May-June.

Figure 5.

Levels of air pollutants and aeroallergens in Philadelphia during the COVID-19 pandemic. (A) Trend lines of weekly averages of daily NO2, ozone, PM10, and PM2.5 measures from 2020 and 2015-2019 sourced from AirNow and AirData, respectively, for the period January 1 to December 31 in Philadelphia. (B) Heatmap of weekly aeroallergen concentrations for tree, weed, mold, and grass pollen measured by a National Allergy Bureau–certified station near Philadelphia during the period March 17 to October 29, 2020. Phases of Philadelphia COVID-19–related public health measures are shown. ppb, Parts per billion.

Discussion

In addition to the devastating morbidity and mortality arising directly from COVID-19,29 , 30 , 34, 35, 36 there have been indirect negative effects on various health outcomes.20 , 21 , 26 , 28 In the case of asthma, however, COVID-19–related public health measures during the initial months of the pandemic reduced disease burden.23, 24, 25 , 27 , 37 , 38 As a continuation of our previous initial observations,23 the in-depth analyses of the effects of COVID-19–related public health measures on asthma activity over a longer period of time provide a unique opportunity to study the environmental triggers of asthma exacerbations. Our current results show that although the relaxation of COVID-19–related public health measures resulted in a recovery of nonacute asthma care to near prepandemic levels, there was a persistence of historically low acute asthma care that corresponded with low respiratory virus positivity until the end of 2020. The current study allows for the analysis of viral trends following deviations from public health interventions during the course of the study, as well as a closer look at the seasonality of the viruses when compared with historical averages due to the increased duration of the observation period. Allergen data during this span have also been included in the current analysis. In addition, analysis of well versus sick outpatient encounters was performed, as was a more detailed analysis of asthma medication prescriptions during this time frame.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a substantial decrease in respiratory viral infections,23 , 26 , 29 , 38 including influenza.23 , 28 , 39 , 40 Consistent with these reports, our results show that the number of positive virus test results decreased and remained lower than the historical average. Specifically, in the ED and satellite care centers between September 2020 and March 2021, when peaks in the number of IFV-A, IFV-B, and RSV infections were observed in previous years, no positive IFV-A, IFV-B, or RSV infections were identified. In addition, the number of positive cases of rhinovirus, a key virus linked to asthma exacerbations,41 , 42 remained lower than historical averages. These trends may not be solely due to behavioral responses or public health interventions, in that after the major US 2020 fall and winter holidays that were accompanied by ill-advised gatherings (eg, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve), the number of respiratory viruses, other than SARS-CoV-2, remained very low even as COVID-19 rates increased. Given the known role of respiratory viral infections as a trigger of asthma exacerbations, it is likely that the sustained decrease in respiratory virus levels strongly contributed to the decrease in asthma encounters in 2020.

Exposure to air pollution and aeroallergens contributes to asthma exacerbations.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Consistent with our previous publication that studied the early phases of the pandemic,23 we did not observe changes to levels of air pollutants that diverged from historical trends; that is, seasonal variability in PM2.5, PM10, and ozone, which peaked during summer 2020, and NO2, which peaked during winter 2020, was consistent with 2015-2019 trends.43 , 44 Similarly, seasonal peaks were observed among aeroallergens from April to June and early September, according to pollen type,11 , 45 but these changes were consistent with historical trends. Previously, we explicitly confirmed that the seasonal decrease in levels of 4 air pollutants in the 2-month period following Philadelphia’s first lockdown period was not statistically significant when compared with historical trends via interrupted time series analysis.23 Here, having expanded the time period of observation, there were even fewer differences between pollution levels across 2020 compared with historical patterns, suggesting that the implementation and relaxation of COVID-19–related public health measures had little effect on levels of PM2.5, PM10, ozone, and NO2 in Philadelphia as measured with regulatory monitors. Similarly, COVID-19–related measures did not influence aeroallergen levels, as illustrated by our results for weed, tree, mold, and grass pollens, which followed expected seasonal trends. We note however that our data have limitations. First, the US Environmental Protection Agency data used comprised monitoring sites that sparsely cover the greater Philadelphia region and do not account for all pollutants that may have changed as a result of public health measures. Second, our aeroallergen data were sourced from a single monitoring site and did not have detailed historical measures available (only ranges). Third, public health interventions may have altered the outdoor pollution and aeroallergen exposure profiles of children due to increased usage of masks, decreased outdoor activity and commuting, and school closures.46 , 47 Given the complex behavioral, environmental, and biological issues relevant to fully understanding the effects of public health interventions on asthma studies, capturing individual-level data is necessary to more fully quantify changes in children’s exposure profiles, as well as to distinguish the impact of these changes on atopic versus nonatopic children with asthma.48

The recovery of nonacute asthma care during the reopening phases suggests that people were willing and able to access health care during this time. Thus, reduced access was not a major driver of the persistently low acute outpatient and inpatient asthma encounters. The persistently decreased prescription levels of maintenance and acute management medications during phases in which routine asthma care encounters were recovering further support that a decrease in asthma exacerbations and symptoms occurred. However, it is possible that fear of coming to the pediatrician’s office or hospital, out of concern for increased SARS-CoV-2 infection risk, drove some of the effect on acute asthma care that we observed. There are additional limitations to our study. Our results showing a substantial decrease in the number of asthma exacerbations along with extremely low levels of respiratory viral infections reflect a single pediatric health care network and may not generalize to other populations. Using an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision classification of asthma may potentially miss asthma admissions that were coded primarily as COVID-19–related. Nevertheless, the observed trends of a decrease in weekly positive respiratory virus test results during the first lockdown, phased reopening, and second lockdown, together with the decrease in acute asthma episodes during the same time frame, suggest that limiting routes through which respiratory viruses are communicable likely substantially decreased asthma exacerbations.

Although the restrictive COVID-19 public health interventions would not be feasible or acceptable long-term given their detrimental consequences on other aspects of health,49, 50, 51 the insights gained during this period may foster greater awareness for the importance of practicing effective strategies to reduce exacerbations. Continued education of patients with asthma and their parents to encourage handwashing, provide anticipatory guidance about travel, adhere to asthma action plans as children return to school,52 consider voluntary masking during respiratory viral seasons in certain settings (eg, large indoor gatherings or while traveling), and follow other Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines to reduce viral transmission53 , 54 could effectively curb asthma exacerbations. As the COVID-19 pandemic subsides and related public health measures are reduced, continued studies of the relationship between viral infection rates and asthma are needed to identify the most effective and acceptable long-term strategies that will maintain reduced asthma exacerbations.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. K08DK116668 to D.A.H., grant nos. R01HL133433, R01HL141992, and P30ES013508 to B.E.H., grant no. K08AI135091 to S.E.H., and grant no. K23HL136842 to C.C.K.), the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (D.A.H.), the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (D.A.H.), the American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (D.A.H.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (S.E.H.), and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute Developmental Awards (D.A.H., S.E.H., and C.C.K.). The content of this work is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository

Table E1.

Demographic characteristics of subjects with asthma by time period and encounter type

| Characteristic | Cohort (n) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2019 |

January 1-December 31, 2020 |

||||

| All (88,039) | Outpatient | Inpatient | Video | All (28,157) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 50,281 (57) | 13,996 (57) | 1739 (57) | 2804 (58) | 16,160 (57) |

| Female | 37,756 (43) | 10,392 (43) | 1290 (43) | 2017 (42) | 11,997 (43) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2926 (3) | 824 (3) | 73 (2) | 140 (3) | 934 (3) |

| Black | 33,495 (38) | 8995 (37) | 2117 (70) | 1328 (28) | 10,690 (38) |

| White | 38,943 (44) | 10,881 (45) | 461 (15) | 2558 (53) | 12,282 (44) |

| Other | 12,204 (14) | 3537 (15) | 373 (12) | 757 (16) | 4082 (14) |

| Unknown | 471 (1) | 151 (1) | 5 (0) | 38 (1) | 169 (1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 79,886 (91) | 21,875 (90) | 2717 (90) | 4231 (88) | 25,209 (90) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 7452 (8) | 2330 (10) | 305 (10) | 538 (11) | 2737 (10) |

| Unknown | 701 (1) | 183 (1) | 7 (0) | 52 (1) | 211 (1) |

| Birth year, n (%) | |||||

| Before 2000 | 6979 (8) | 183 (1) | 6 (0) | 74 (2) | 237 (1) |

| 2000-2004 | 18,668 (21) | 3677 (15) | 281 (9) | 665 (14) | 4189 (15) |

| 2005-2009 | 25,468 (29) | 7564 (31) | 591 (20) | 1224 (25) | 8468 (30) |

| 2010-2014 | 26,448 (30) | 7932 (33) | 963 (32) | 1572 (33) | 9168 (33) |

| 2015 or later | 10,476 (12) | 5032 (21) | 1188 (39) | 1286 (27) | 6095 (22) |

| Payer type, n (%) | |||||

| Non-Medicaid | 49,551 (56) | 13,069 (54) | 762 (25) | 2865 (59) | 14,842 (53) |

| Medicaid | 38,488 (44) | 11,319 (46) | 2267 (75) | 1956 (41) | 13,315 (47) |

ICU, Intensive care unit.

Outpatient (Primary-Well, Primary-Sick, Specialty); Inpatient (ED, Inpatient, ICU); Video (Primary-Video, Specialty-Video).

Table E2.

Asthma medication classes

| Medication ID no. | Name | Class |

|---|---|---|

| 61180 | Decadron IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 61181 | Decadron IV | Systemic steroid |

| 61183 | Decadron OR | Systemic steroid |

| 132559 | Dex Combo 8-4 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132710 | Dex Combo IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 132560 | Dex LA 16 16 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132711 | Dex LA 16 IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 132561 | Dex LA 8 8 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132712 | Dex LA 8 IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 130359 | Dexameth SOD PHOS-BUPIV-LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 90302 | Dexamethasone (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 61547 | Dexamethasone (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200162 | Dexamethasone 0.1 mg/mL (D5W) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 200200163 | Dexamethasone 0.1 mg/mL (NSS) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 2762 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200499 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic Steroid |

| 2759 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL OR ELIX | Systemic Steroid |

| 2760 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 2763 | Dexamethasone 0.75 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 2764 | Dexamethasone 1 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200201009 | Dexamethasone 1 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 200200164 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL (D5W) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 200200874 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL (NSS) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 21292 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 200200501 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL OR CONC (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 135377 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135378 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135379 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 2765 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200502 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2766 | Dexamethasone 2 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200201008 | Dexamethasone 2 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2767 | Dexamethasone 4 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200503 | Dexamethasone 4 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 200200504 | Dexamethasone 4 mg/mL (undiluted) injection (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 200200165 | Dexamethasone 4 mg/mL (undiluted) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 2768 | Dexamethasone 6 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200505 | Dexamethasone 6 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 132777 | Dexamethasone ACE & SOD PHOS | Systemic steroid |

| 132551 | Dexamethasone ACE & SOD PHOS 8-4 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132713 | Dexamethasone ACE & SOD PHOS IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 90303 | Dexamethasone acetate | Systemic steroid |

| 29197 | Dexamethasone acetate 16 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 2769 | Dexamethasone acetate 8 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 61549 | Dexamethasone acetate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 2770 | Dexamethasone acetate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 27267 | Dexamethasone base POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 200200166 | Dexamethasone injection custom orderable | Systemic steroid |

| 200200506 | Dexamethasone injection custom orderable (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2758 | Dexamethasone intensol 1 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 61551 | Dexamethasone intensol OR | Systemic steroid |

| 61554 | Dexamethasone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 18270 | Dexamethasone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 130355 | Dexamethasone SOD PHOS & BUPIV | Systemic steroid |

| 130356 | Dexamethasone SOD PHOS-LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 121371 | Dexamethasone SOD phosphate PF 10 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 121730 | Dexamethasone SOD phosphate PF IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 200201236 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (CHEMO) 4 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 90304 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 2771 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 10 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 200201160 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 10 mg/mL IJ SOLN (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 128185 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 100 mg/10 mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 128184 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 120 mg/30 mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 128183 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 20 mg/5 mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 2772 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 4 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 200201065 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 4 mg/mL INH SOLN CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 61557 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 61558 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate IV | Systemic steroid |

| 2776 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 135753 | Dexpak 10 day 1.5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 97925 | Dexpak 10 day OR | Systemic steroid |

| 135749 | Dexpak 13 day 1.5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 61586 | Dexpak 13 day OR | Systemic steroid |

| 135755 | Dexpak 6 day 1.5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 100127 | Dexpak 6 day OR | Systemic steroid |

| 130145 | Doubledex 10 mg/mL IJ KIT | Systemic steroid |

| 130264 | Doubledex IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 70802 | Medrol (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 17892 | Medrol 16 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 5790 | Medrol 2 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 5792 | Medrol 32 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 17891 | Medrol 4 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 135742 | Medrol 4 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 5793 | Medrol 8 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 70803 | Medrol OR | Systemic steroid |

| 71141 | Methylpred 40 IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 130360 | Methylprednisol & BUPIV & LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 90309 | Methylprednisolone | Systemic steroid |

| 128079 | Methylprednisolone & lidocaine IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 200200507 | Methylprednisolone (CHEMO) injection custom orderable | Systemic steroid |

| 71143 | Methylprednisolone (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 5957 | Methylprednisolone 16 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 12408 | Methylprednisolone 2 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 12410 | Methylprednisolone 32 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 5958 | Methylprednisolone 4 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 135372 | Methylprednisolone 4 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 12411 | Methylprednisolone 8 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 128116 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 132562 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO 40-10 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132542 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO 80-10 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132732 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 90310 | Methylprednisolone acetate | Systemic steroid |

| 132539 | Methylprednisolone acetate 100 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 5959 | Methylprednisolone acetate 20 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 5960 | Methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 200201903 | Methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg/mL IJ SUSP (IR use only) C∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 5961 | Methylprednisolone acetate 80 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 71145 | Methylprednisolone acetate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 121372 | Methylprednisolone acetate PF 40 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 121373 | Methylprednisolone acetate PF 80 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 121778 | Methylprednisolone acetate PF IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 20399 | Methylprednisolone acetate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 200200293 | Methylprednisolone injection custom orderable | Systemic steroid |

| 71147 | Methylprednisolone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 20398 | Methylprednisolone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 200200508 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (CHEMO) 1 mg/mL (NSS) INJECT∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 200200509 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (CHEMO) 1000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200510 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (CHEMO) 125 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200201004 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (CHEMO) 125 mg/mL (SWFI) INJ∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 200200511 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (CHEMO) 40 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200201002 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (CHEMO) 40 mg/mL (SWFI) INJE∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 90311 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 52078 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 1 g IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200294 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 1 mg/mL (NSS) injection CUST∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 12412 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 1000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 12413 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 125 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200201001 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 125 mg/mL (SWFI) injection C∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 12414 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 2000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 12415 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 40 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200999 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 40 mg/mL (SWFI) injection CU∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 12416 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 500 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 71149 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 89026 | Millipred 10 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 97492 | Millipred 5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 135762 | Millipred DP 12-day 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 111603 | Millipred DP 12-day OR | Systemic steroid |

| 135756 | Millipred DP 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135757 | Millipred DP 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 100265 | Millipred DP OR | Systemic steroid |

| 89183 | Millipred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 33929 | Orapred 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 51263 | Orapred ODT 10 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 50493 | Orapred ODT 15 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 51264 | Orapred ODT 30 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 73649 | Orapred ODT OR | Systemic steroid |

| 73650 | Orapred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 97196 | Pediapred 6.7 (5 base) mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 74412 | Pediapred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 90312 | Prednisolone | Systemic steroid |

| 100776 | Prednisolone 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 13018 | Prednisolone 15 mg/5 mL OR SYRP | Systemic steroid |

| 135373 | Prednisolone 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135374 | Prednisolone 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 7711 | Prednisolone 5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 90313 | Prednisolone acetate (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 108953 | Prednisolone acetate 16.7 (15 base) mg/5 mL OR SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 75589 | Prednisolone acetate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 109427 | Prednisolone acetate OR | Systemic steroid |

| 7716 | Prednisolone acetate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 20923 | Prednisolone anhydrous POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 75593 | Prednisolone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 7712 | Prednisolone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 75595 | Prednisolone SOD phosphate OR | Systemic steroid |

| 90314 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 51252 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 10 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 89025 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 10 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 50481 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 200201856 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg/5 mL (SWISH & SPIT) OR S∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 33930 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 200200533 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN (CHEMO) CUS∗ | Systemic steroid |

| 97477 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 20 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 121526 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 25 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 51253 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 30 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 96082 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 6.7 (5 base) mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 75598 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate OR | Systemic steroid |

| 20439 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 90315 | Prednisone | Systemic steroid |

| 75601 | Prednisone (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200351 | Prednisone 0.5 mg/mL OR SOL CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 7721 | Prednisone 1 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200492 | Prednisone 1 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 120527 | Prednisone 1 mg OR TBEC | Systemic steroid |

| 135431 | Prednisone 10 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135432 | Prednisone 10 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 7722 | Prednisone 10 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200493 | Prednisone 10 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 120528 | Prednisone 2 mg OR TBEC | Systemic steroid |

| 7723 | Prednisone 2.5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200494 | Prednisone 2.5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 7724 | Prednisone 20 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200495 | Prednisone 20 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 135375 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135376 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 7725 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200496 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) CUSTOM | Systemic steroid |

| 120529 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TBEC | Systemic steroid |

| 7720 | Prednisone 5 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 7718 | Prednisone 5 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 7726 | Prednisone 50 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 22674 | Prednisone intensol 5 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 75602 | Prednisone intensol OR | Systemic steroid |

| 75603 | Prednisone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 7727 | Prednisone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 7732 | Prelone 15 mg/5 mL OR SYRP | Systemic steroid |

| 75620 | Prelone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 8767 | Solu-Medrol 1000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8768 | Solu-Medrol 125 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8769 | Solu-Medrol 2 g IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8770 | Solu-Medrol 40 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8771 | Solu-Medrol 500 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 79793 | Solu-Medrol IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 79797 | Solurex IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 79798 | Solurex LA IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 80064 | Sterapred 12 day OR | Systemic steroid |

| 80065 | Sterapred DS 12 day OR | Systemic steroid |

| 80066 | Sterapred DS OR | Systemic steroid |

| 80067 | Sterapred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 36549 | Accuneb 0.63 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 36550 | Accuneb 1.25 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 53821 | Accuneb IN | β-agonist |

| 54377 | Airet IN | β-agonist |

| 91225 | Albuterol | β-agonist |

| 54543 | Albuterol IN | β-agonist |

| 20261 | Albuterol POWD | β-agonist |

| 91226 | Albuterol sulfate | β-agonist |

| 311 | Albuterol sulfate (2.5 mg/3 mL) 0.083% INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 312 | Albuterol sulfate (5 mg/mL) 0.5% INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 200200745 | Albuterol sulfate (5 mg/mL) 0.5% NEB continuous custom | β-agonist |

| 36541 | Albuterol sulfate 0.63 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 36542 | Albuterol sulfate 1.25 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 132129 | Albuterol sulfate 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AEPB | β-agonist |

| 315 | Albuterol sulfate 2 mg OR TABS | β-agonist |

| 314 | Albuterol sulfate 2 mg/5 mL OR SYRP | β-agonist |

| 316 | Albuterol sulfate 4 mg OR TABS | β-agonist |

| 39219 | Albuterol sulfate ER 4 mg OR TB12 | β-agonist |

| 39220 | Albuterol sulfate ER 8 mg OR TB12 | β-agonist |

| 123418 | Albuterol sulfate ER OR | β-agonist |

| 21155 | Albuterol sulfate HFA 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AERS | β-agonist |

| 200200995 | Albuterol sulfate HFA 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AERS (ED HOM∗) | β-agonist |

| 200200994 | Albuterol sulfate HFA 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AERS (OR USE∗) | β-agonist |

| 98773 | Albuterol sulfate HFA INH | β-agonist |

| 54545 | Albuterol sulfate INH | β-agonist |

| 54546 | Albuterol sulfate OR | β-agonist |

| 317 | Albuterol sulfate POWD | β-agonist |

| 2002001992 | Albuterol sulfate variable dose for pyxis | β-agonist |

| 91234 | Levalbuterol HCL (sympathomimetics) | β-agonist |

| 37337 | Levalbuterol HCL 0.31 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 29159 | Levalbuterol HCL 0.63 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 44604 | Levalbuterol HCL 1.25 mg/0.5 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 29160 | Levalbuterol HCL 1.25 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 69516 | Levalbuterol HCL INH | β-agonist |

| 91235 | Levalbuterol tartrate | β-agonist |

| 49020 | Levalbuterol tartrate 45 μg/ACT INH AERO | β-agonist |

| 69517 | Levalbuterol tartrate INH | β-agonist |

| 50377 | Proair HFA 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AERS | β-agonist |

| 75956 | Proair HFA IN | β-agonist |

| 132126 | Proair respiclick 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AEPB | β-agonist |

| 132374 | Proair respiclick INH | β-agonist |

| 21277 | Proventil HFA 108 (90 base) μg/ACT INH AERS | β-agonist |

| 76250 | Proventil HFA INH | β-agonist |

| 76251 | Proventil INH | β-agonist |

| 76252 | Proventil OR | β-agonist |

| 200200406 | Terbutaline 0.1% nebulization SOLN custom | β-agonist |

| 91239 | Terbutaline sulfate | β-agonist |

| 200200937 | Terbutaline sulfate 0.1 mg/mL IJ SOLN custom | β-agonist |

| 13430 | Terbutaline sulfate 1 mg/mL IJ SOLN | β-agonist |

| 200201165 | Terbutaline sulfate 1 mg/mL IJ SOLN (SC use only) | β-agonist |

| 200200407 | Terbutaline sulfate 1 mg/mL SUSP custom | β-agonist |

| 13432 | Terbutaline sulfate 2.5 mg OR TABS | β-agonist |

| 13433 | Terbutaline sulfate 5 mg OR TABS | β-agonist |

| 81143 | Terbutaline sulfate IJ | β-agonist |

| 200200938 | Terbutaline sulfate injection custom orderable | β-agonist |

| 81144 | Terbutaline sulfate OR | β-agonist |

| 20433 | Terbutaline sulfate POWD | β-agonist |

| 37396 | Xopenex 0.31 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 29270 | Xopenex 0.63 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 29271 | Xopenex 1.25 mg/3 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 44598 | Xopenex concentrate 1.25 mg/0.5 mL INH NEBU | β-agonist |

| 83997 | Xopenex concentrate INH | β-agonist |

| 49017 | Xopenex HFA 45 μg/ACT INH AERO | β-agonist |

| 83998 | Xopenex HFA INH | β-agonist |

| 83999 | Xopenex INH | β-agonist |

| 54262 | Aerobid INH | ICS |

| 54263 | Aerobid-M INH | ICS |

| 127561 | Aerospan 80 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 127718 | Aerospan INH | ICS |

| 96592 | Alvesco 160 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 96591 | Alvesco 80 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 97729 | Alvesco INH | ICS |

| 130919 | Arnuity ellipta 100 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 130920 | Arnuity ellipta 200 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 130972 | Arnuity ellipta IN | ICS |

| 47449 | Asmanex 120 metered doses 220 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 55726 | Asmanex 120 metered doses IN | ICS |

| 47450 | Asmanex 14 metered doses 220 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 55727 | Asmanex 14 metered doses INH | ICS |

| 89591 | Asmanex 30 metered doses 110 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 47447 | Asmanex 30 metered doses 220 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 55728 | Asmanex 30 metered doses INH | ICS |

| 47448 | Asmanex 60 metered doses 220 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 55729 | Asmanex 60 metered doses INH | ICS |

| 111284 | Asmanex 7 metered doses 110 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 111529 | Asmanex 7 metered doses INH | ICS |

| 130881 | Asmanex HFA 100 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 130893 | Asmanex HFA 200 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 130973 | Asmanex HFA INH | ICS |

| 56112 | Azmacort INH | ICS |

| 91254 | Beclomethasone dipropionate (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 33588 | Beclomethasone dipropionate 40 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 33589 | Beclomethasone dipropionate 80 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 56626 | Beclomethasone dipropionate INH | ICS |

| 56627 | Beclovent INH | ICS |

| 91255 | Budesonide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 33341 | Budesonide 0.25 mg/2 mL INH SUSP | ICS |

| 33342 | Budesonide 0.5 mg/2 mL INH SUSP | ICS |

| 200201034 | Budesonide 0.5 mg/2 mL NEB for PO use | ICS |

| 85108 | Budesonide 1 mg/2 mL INH SUSP | ICS |

| 98957 | Budesonide 180 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 98956 | Budesonide 90 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 98788 | Budesonide INH | ICS |

| 98448 | Ciclesonide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 96103 | Ciclesonide 160 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 96102 | Ciclesonide 80 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 97832 | Ciclesonide INH | ICS |

| 98924 | Flovent diskus 100 μg/BLIST INH AEPB | ICS |

| 98925 | Flovent diskus 250 μg/BLIST INH AEPB | ICS |

| 53294 | Flovent diskus 50 μg/BLIST INH AEPB | ICS |

| 64815 | Flovent diskus INH | ICS |

| 46255 | Flovent HFA 110 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 46256 | Flovent HFA 220 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 46254 | Flovent HFA 44 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 64816 | Flovent HFA INH | ICS |

| 64817 | Flovent INH | ICS |

| 64818 | Flovent rotadisk INH | ICS |

| 91256 | Flunisolide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 127699 | Flunisolide HFA | ICS |

| 127438 | Flunisolide HFA 80 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 127758 | Flunisolide HFA INH | ICS |

| 64856 | Flunisolide INH | ICS |

| 20361 | Flunisolide POWD | ICS |

| 131120 | Fluticasone furoate (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 130716 | Fluticasone furoate 100 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 130717 | Fluticasone furoate 200 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 131018 | Fluticasone furoate INH | ICS |

| 91257 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) | ICS |

| 32750 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) 100 μg/BLIST INH AEPB | ICS |

| 32751 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) 250 μg/BLIST INH AEPB | ICS |

| 32749 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) 50 μg/BLIST INH AEPB | ICS |

| 64934 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) INH | ICS |

| 91258 | Fluticasone propionate HFA | ICS |

| 46046 | Fluticasone propionate HFA 110 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 46047 | Fluticasone propionate HFA 220 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 46045 | Fluticasone propionate HFA 44 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 134419 | Fluticasone propionate HFA INH | ICS |

| 91259 | Mometasone furoate (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 130882 | Mometasone furoate 100 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 89590 | Mometasone furoate 110 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 130883 | Mometasone furoate 200 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS |

| 47345 | Mometasone furoate 220 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS |

| 71565 | Mometasone furoate INH | ICS |

| 33535 | Pulmicort 0.25 mg/2 mL INH SUSP | ICS |

| 33536 | Pulmicort 0.5 mg/2 mL INH SUSP | ICS |

| 85111 | Pulmicort 1 mg/2 mL INH SUSP | ICS |

| 99899 | Pulmicort flexhaler 180 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 99900 | Pulmicort flexhaler 90 μg/ACT INH AEPB | ICS |

| 76405 | Pulmicort flexhaler INH | ICS |

| 76406 | Pulmicort INH | ICS |

| 76407 | Pulmicort turbuhaler INH | ICS |

| 33585 | Qvar 40 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 33586 | Qvar 80 μg/ACT INH AERS | ICS |

| 76802 | Qvar INH | ICS |

| 91260 | Triamcinolone acetonide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 85453 | Triamcinolone acetonide INH | ICS |

| 83089 | Vanceril double strength INH | ICS |

| 83090 | Vanceril INH | ICS |

| 105585 | Advair diskus 100-50 μg/dose INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 105588 | Advair diskus 250-50 μg/dose INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 105589 | Advair diskus 500-50 μg/dose INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 54204 | Advair diskus INH | ICS + LABA |

| 50623 | Advair HFA 115-21 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 50624 | Advair HFA 230-21 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 50622 | Advair HFA 45-21 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 54205 | Advair HFA INH | ICS + LABA |

| 125719 | Breo ellipta 100-25 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 132901 | Breo ellipta 200-25 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 125944 | Breo ellipta INH | ICS + LABA |

| 91246 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate | ICS + LABA |

| 53024 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate 160-4.5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 53023 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate 80-4.5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 57629 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate INH | ICS + LABA |

| 110610 | Dulera 100-5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110611 | Dulera 200-5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110811 | Dulera INH | ICS + LABA |

| 126085 | Fluticasone furoate-vilanterol | ICS + LABA |

| 125641 | Fluticasone furoate-vilanterol 100-25 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 132806 | Fluticasone furoate-vilanterol 200-25 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 125999 | Fluticasone furoate-vilanterol IN | ICS + LABA |

| 91247 | Fluticasone-salmeterol | ICS + LABA |

| 105249 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 100-50 μg/dose INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 50619 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 115-21 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 50620 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 230-21 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 105250 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 250-50 μg/dose INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 50618 | FLuticasone-salmeterol 45-21 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 105251 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 500-50 μg/dose INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 64938 | Fluticasone-salmeterol INH | ICS + LABA |

| 111224 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM | ICS + LABA |

| 110576 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM 100-5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110577 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM 200-5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110835 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM IN | ICS + LABA |

| 53239 | Symbicort 160-4.5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 53238 | Symbicort 80-4.5 μg/ACT INH AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 80691 | Symbicort INH | ICS + LABA |

| 128121 | Umeclidinium-vilanterol | ICS + LABA |

| 127865 | Umeclidinium-vilanterol 62.5-25 μg/INH INH AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 128105 | Umeclidinium-vilanterol INH | ICS + LABA |

| 30756 | Accolate 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 21303 | Accolate 20 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 53764 | Accolate OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 91262 | Montelukast sodium (leukotriene modulators) | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26447 | Montelukast sodium 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 31645 | Montelukast sodium 4 mg OR CHEW | Leukotriene modulators |

| 41211 | Montelukast sodium 4 mg OR PKT | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26448 | Montelukast sodium 5 mg OR CHEW | Leukotriene modulators |

| 71666 | Montelukast sodium OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26454 | Singulair 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 31649 | Singulair 4 mg OR CHEW | Leukotriene modulators |

| 41210 | Singulair 4 mg OR PKT | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26451 | Singulair 5 mg OR CHEW | Leukotriene modulators |

| 79047 | Singulair OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 91263 | Zafirlukast | Leukotriene modulators |

| 30767 | Zafirlukast 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 21309 | Zafirlukast 20 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 84136 | Zafirlukast OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 91261 | Zileuton | Leukotriene modulators |

| 22305 | Zileuton 600 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 85485 | Zileuton ER 600 mg OR TB12 | Leukotriene modulators |

| 120894 | Zileuton ER OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 84194 | Zileuton OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 22304 | Zyflo 600 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 85530 | Zyflo CR 600 mg OR TB12 | Leukotriene modulators |

| 85882 | Zyflo CR OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 84345 | Zyflo OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 134493 | Mepolizumab | Biologics |

| 134274 | Mepolizumab 100 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 134437 | Mepolizumab SC | Biologics |

| 134298 | Nucala 100 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 134446 | Nucala SC | Biologics |

| 91264 | Omalizumab | Biologics |

| 41330 | Omalizumab 150 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 73347 | Omalizumab SC | Biologics |

| 41342 | Xolair 150 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 83995 | Xolair SC | Biologics |

| 120900 | Aclidinium bromide | Anticholinergics |

| 120515 | Aclidinium bromide 400 μg/ACT INH AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 120732 | Aclidinium bromide INH | Anticholinergics |

| 46720 | Atrovent HFA 17 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 55931 | Atrovent HFA IN | Anticholinergics |

| 55932 | Atrovent IN | Anticholinergics |

| 134491 | Glycopyrrolate (bronchodilators-anticholinergics) | Anticholinergics |

| 134424 | Glycopyrrolate INH | Anticholinergics |

| 130918 | Incruse ellipta 62.5 μg/INH INH AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 131033 | Incruse ellipta INH | Anticholinergics |

| 91220 | Ipratropium bromide (bronchodilators-anticholinergics) | Anticholinergics |

| 14727 | Ipratropium bromide 0.02% INH SOLN | Anticholinergics |

| 91221 | Ipratropium bromide HFA | Anticholinergics |

| 46527 | Ipratropium bromide HFA 17 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 68438 | Ipratropium bromide HFA INH | Anticholinergics |

| 68439 | Ipratropium bromide IN | Anticholinergics |

| 20367 | Ipratropium bromide POWD | Anticholinergics |

| 134455 | Seebri neohaler INH | Anticholinergics |

| 43683 | Spiriva handihaler 18 μg INH CAPS | Anticholinergics |

| 79945 | Spiriva handihaler INH | Anticholinergics |

| 133764 | Spiriva respimat 1.25 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 130566 | Spiriva respimat 2.5 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 130663 | Spiriva respimat INH | Anticholinergics |

| 91222 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate | Anticholinergics |

| 133714 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate 1.25 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 43672 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate 18 μg INH CAPS | Anticholinergics |

| 130394 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate 2.5 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 81562 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate INH | Anticholinergics |

| 120704 | Tudorza pressair 400 μg/ACT INH AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 120880 | Tudorza pressair INH | Anticholinergics |

| 131119 | Umeclidinium bromide | Anticholinergics |

| 130705 | Umeclidinium bromide 62.5 μg/INH INH AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 131098 | Umeclidinium bromide INH | Anticholinergics |

| 91245 | Ipratropium-albuterol | Anticholinergics |

| 97202 | Ipratropium-albuterol 0.5-2.5 (3) mg/3 mL INH SOLN | Anticholinergics |

| 16477 | Ipratropium-albuterol 18-103 μg/ACT INH AERO | Anticholinergics |

| 119838 | Ipratropium-albuterol 20-100 μg/ACT INH AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 98087 | Ipratropium-albuterol INH | Anticholinergics |

AERS, AERO, Aerosolized; CAPS, capsule; CHEMO, chemotherapy; CONC, concentrate; CUST, custom; Dex, dexamethasone; D5W, dextrose 5% in water; ELIX, elixer; ER, extended release; HCL, hydrochloride; HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; IJ, IN, INJ, INJECT, injection; INH, INHAL, inhalation; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LIDO, lidocaine; NEBU, NEB, nebulizer; NSS, normal saline solution; OR, oral; PAK, pack; PHOS, phosphage; PKT, packet; PO, per os (by mouth); POWD, powder; SC, subcutaneous; SOD, sodium; SOLN, SOL, solution; SUCC, succinate; SUSP, suspension; SWFI, sterile water for injection; SYRP, syrup; TABS, tablets; TBEC, enteric-coated tablet; TBPK, tablet pack.

Table E3.

Summary of virus-specific tests ordered and % of virus-specific positive test results

| Virus | Yearly averages (range) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average 2015-2019 |

2020 |

2020 (Jan-Mar) |

2020 (Apr-Dec) |

2021 (Jan-Apr) |

||||||

| Total tests | % positive test results | Total tests | % positive test results | Total tests | % positive test results | Total tests | % positive test results | Total tests | % positive test results | |

| IFV-A | 458 (19.8-1479) | 7.24 (0-27.0) | 1586 (1.00-5528) | 7.19 (0-28.0) | 4692 (3452- 5528) | 21.6 (17.8- 28.0) | 32.5 (1.00-123) | 0 (0) | 32.5 (2.00-56.0) | 0 (0) |

| IFV-B | 458 (19.8- 1479) | 3.31 (0- 8.69) | 1586 (0- 5528) | 7.08 (0- 30.5) | 4692 (3452- 5528) | 20.4 (8.66- 30.5) | 32.5 (1.00-123) | 0.43 (0- 2.56) | 32.5 (2.00-56.0) | 0.64 (0- 2.56) |

| RSV | 258 (40.2- 825) | 12.7 (1.77- 38.0) | 108 (17- 630) | 4.69 (0- 26.1) | 308 (136- 630) | 16.5 (5.08- 26.1) | 41.0 (17.0-126) | 0.74 (0- 5.88) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 3.39 (0- 9.38) |

| Rhinovirus | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 39.7 (24.6-56.1) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 20.1 (7.69- 38.5) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 22.8 (16.3- 31.0) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 19.2 (7.69- 38.5) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 27.1 (9.09- 37.5) |

| COVID-19 | 2250 (1258- 4928) | 5.29 (2.05- 11.5) | 2250 (1258- 4928) | 5.29 (2.05- 11.5) | 2250 (1258- 4928) | 5.29 (2.05- 11.5) | 2148 (1501- 2648) | 7.27 (5.40- 8.32) | ||

| Adenovirus | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 10.3 (5.56- 13.8) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 3.85 (0- 11.6) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 9.00 (7.50- 11.6) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 2.13 (0- 4.96) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 5.40 (3.13- 7.69) |

| Non–COVID-19 coronavirus | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 3.40 (0.60- 9.06) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 4.03 (0- 17.5) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 13.2 (10.4- 17.5) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 0.95 (0- 5.26) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 1.82 (0- 4.17) |

| Metapneumovirus | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 5.80 (0.30-12.2) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 3.54 (0-11.8) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 11.5 (11.3- 11.8) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 0.89 (0- 4.13) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 0.52 (0- 2.08) |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 2.60 (0.37- 6.89) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 0.36 (0- 2.50) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 1.45 (0.52- 2.50) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 0 (0) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 0 (0) |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 0.89 (0-2.74) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 0.13 (0- 1.25) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 0.53 (0- 1.25) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 0 (0) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 0 (0) |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 87.2 (39.0-129) | 6.09 (1.10- 17.8) | 91.3 (17.0-577) | 0.44 (0- 3.03) | 244 (76.0- 577) | 0.46 (0- 1.39) | 40.3 (17.0-121) | 0.43 (0- 3.03) | 32.0 (22.0-48.0) | 1.56 (0- 6.25) |

During the first lockdown that occurred from March 18 to June 5, 2020, social distancing measures were mandated, and schools, nonessential businesses, and dine-in restaurants/bars were closed. A phased reopening consisted of (1) an initial reopening between June 6 and June 26, 2020, when most businesses in Philadelphia county could remain open at limited capacity consistent with public health guidelines, and (2) an expanded reopening between June 27 and November 15, 2020, during which time restaurants could increase to 50% capacity for indoor dining and increased crowd capacity limits for indoor and outdoor events were allowed. November 16, 2020, marked the beginning of the second lockdown with restrictions that included no indoor dining at restaurants, capacity limits at retail stores and religious institutions, the closure of gyms, libraries, and certain entertainment businesses, telework for office workers unless not possible, no indoor gatherings, reduced size limits on outdoor gatherings, and no youth or school sports. This second lockdown was lifted January 4, 2021, though previously mandated social distancing and masking policies remained. In addition, although there was substantial variability in primary and secondary school opening, public Philadelphia county schools remained entirely virtual until March 8, 2021, when a phased reopening began with K-2 schools.

References

- 1.Zahran H.S., Bailey C.M., Damon S.A., Garbe P.L., Breysse P.N. Vital signs: asthma in children—United States, 2001-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:149–155. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6705e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of asthma. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:68. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jartti T., Gern J.E. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corne J.M., Marshall C., Smith S., Schreiber J., Sanderson G., Holgate S.T., et al. Frequency, severity, and duration of rhinovirus infections in asthmatic and non-asthmatic individuals: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:831–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirabelli M.C., Vaidyanathan A., Flanders W.D., Qin X., Garbe P. Outdoor PM2.5, ambient air temperature, and asthma symptoms in the past 14 days among adults with active asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1882–1890. doi: 10.1289/EHP92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orellano P., Quaranta N., Reynoso J., Balbi B., Vasquez J. Effect of outdoor air pollution on asthma exacerbations in children and adults: systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strickland M.J., Darrow L.A., Klein M., Flanders W.D., Sarnat J.A., Waller L.A., et al. Short-term associations between ambient air pollutants and pediatric asthma emergency department visits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:307–316. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1201OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keet C.A., Keller J.P., Peng R.D. Long-term coarse particulate matter exposure is associated with asthma among children in Medicaid. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:737–746. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1267OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achakulwisut P., Brauer M., Hystad P., Anenberg S.C. Global, national, and urban burdens of paediatric asthma incidence attributable to ambient NO2 pollution: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3:e166–e178. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson H.M., Lemanske R.F., Jr., Arron J.R., Holweg C.T.J., Rajamanickam V., Gangnon R.E., et al. Relationships among aeroallergen sensitization, peripheral blood eosinophils, and periostin in pediatric asthma development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Roos A.J., Kenyon C.C., Zhao Y., Moore K., Melly S., Hubbard R.A., et al. Ambient daily pollen levels in association with asthma exacerbation among children in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Environ Int. 2020;145:106138. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao J., Hu J., He G., Liu T., Kang M., Rong Z., et al. The time-varying transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and synchronous public health interventions in China. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei H., Xu M., Wang X., Xie Y., Du X., Chen T., et al. Nonpharmaceutical interventions used to control COVID-19 reduced seasonal influenza transmission in China. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1780–1783. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Distante C., Piscitelli P., Miani A. Covid-19 outbreak progression in Italian regions: approaching the peak by the end of March in Northern Italy and first week of April in Southern Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3025. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lusignan S., Bernal J.L., Zambon M., Akinyemi O., Amirthalingam G., Andrews N., et al. Emergence of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19): protocol for extending surveillance used by the Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre and Public Health England. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6 doi: 10.2196/18606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston S.L. Asthma and COVID-19: is asthma a risk factor for severe outcomes? Allergy. 2020;75:1543–1545. doi: 10.1111/all.14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hegde S. Does asthma make COVID-19 worse? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:352. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Floyd G.C., Dudley J.W., Xiao R., Feudtner C., Taquechel K., Miller K., et al. Prevalence of asthma in hospitalized and non-hospitalized children with COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2077–2079.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez F.D. Asthma in the time of COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:785–786. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202102-0389ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scquizzato T., Landoni G., Paoli A., Lembo R., Fominskiy E., Kuzovlev A., et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2020;157:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huseynova R., Bin Mahmoud L., Abdelrahim A., Al Hemaid M., Almuhaini M.S., Jaganathan P.P., et al. Prevalence of preterm birth rate during COVID-19 lockdown in a tertiary care hospital, Riyadh. Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.13634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenyon C.C., Hill D.A., Henrickson S.E., Bryant-Stephens T.C., Zorc J.J. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2774–2776.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taquechel K., Diwadkar A.R., Sayed S., Dudley J.W., Grundmeier R.W., Kenyon C.C., et al. Pediatric asthma health care utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;8:3378–3387.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simoneau T., Greco K.F., Hammond A., Nelson K., Gaffin J.M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric emergency department use for asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:717–719. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-765RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salciccioli J.D., She L., Tulchinsky A., Rockhold F., Cardet J.C., Israel E. Effect of Covid19 on asthma exacerbation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2896–2899.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partridge E., McCleery E., Cheema R., Nakra N., Lakshminrusimha S., Tancredi D.J., et al. Evaluation of seasonal respiratory virus activity before and after the statewide COVID-19 Shelter-in-Place Order in Northern California. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antoon J.W., Williams D.J., Thurm C., Bendel-Stenzel M., Spauling A.B., Teufel R.J., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:294–297. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen S.J., Azziz-Baumgartner E., Budd A.P., Brammer L., Sullivan S., Fasce Pineda R., et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1305–1309. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo K.H., Bae D.J., Kim J.N., Lee H.S., Kim Y.H., Park J.S., et al. Prevalence of respiratory viral infections in Korean adult asthmatics with acute exacerbations: comparison with those with stable state. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:491–498. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teichtahl H., Buckmaster N., Pertnikovs E. The incidence of respiratory tract infection in adults requiring hospitalization for asthma. Chest. 1997;112:591–596. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.AirNow-Tech. AirNow: Air Quality Data Management Analysis. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://airnowtech.org/

- 32.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Pre-generated data files. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://aqs.epa.gov/aqsweb/airdata/download_files.html

- 33.American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology. National Allergy Bureau (NAB) pollen and mold counts. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.aaaai.org/global/nab-pollen-counts

- 34.Guijon O.L., Morphew T., Ehwerhemuepha L., Galant S.P. Evaluating the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on asthma morbidity: a comprehensive analysis of potential influencing factors. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonett S., Petsis D., Dowshen N., Bauermeister J., Wood S.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on STI/HIV testing among adolescents in a large pediatric primary care network. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:e91–e93. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leff R.A., Setzer E., Cicero M.X., Auerbach M. Changes in pediatric emergency department visits for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26:33–38. doi: 10.1177/1359104520972453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruizinga M.D., Peeters D., van Veen M., van Houten M., Wieringa J., Noordzij J.G., et al. The impact of lockdown on pediatric ED visits and hospital admissions during the COVID19 pandemic: a multicenter analysis and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:2271–2279. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04015-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papadopoulos N.G., Mathioudakis A.G., Custovic A., Deschildre A., Phipatanakul W., Wong G., et al. Childhood asthma outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the PeARL multinational cohort. Allergy. 2021;76:1765–1775. doi: 10.1111/all.14787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]