Abstract

Agriculture's beginnings resulted in the domestication of numerous plant species as well as the use of natural resources. Food grain production took about 10,000 years to reach a billion tonnes in 1960, however, it took only 40 years to achieve 2 billion tonnes in year 2000. The creation of genetically modified crops, together with the use of enhanced agronomic practices, resulted in this remarkable increase, dubbed the "Green Revolution". Plants and bacteria that interact with each other in nature are co-evolving, according to Red Queen dynamics. Plant microorganisms, also known as plant microbiota, are an essential component of plant life. Plant–microbe (PM) interactions can be beneficial or harmful to hosts, depending on the health impact. The significance of microbiota in plant growth promotion (PGP) and stress resistance is well known. Our understanding of the community composition of the plant microbiome and important driving forces has advanced significantly. As a result, utilising the plant microbiota is a viable strategy for the next Green Revolution for meeting food demand. The utilisation of newer methods to understand essential genetic and molecular components of the multiple PM interactions is required for their application. The use of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas-mediated genome editing (GE) techniques to investigate PM interactions is of tremendous interest. The implementation of GE techniques to boost the ability of microorganisms or plants for agronomic trait development will be enabled by a comprehensive understanding of PM interactions. This review focuses on using GE approaches to investigate the principles of PM interactions, disease resistance, PGP activity, and future implications in agriculture in plants or associated microbiota.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas 9, Rhizobacteria

Introduction

The seven-fold increase in the world population over the last two millennia amplified humanity’s impact on the natural environment. With every 1% rise in the world population every year, the global world population is expected to reach 11.2 billion by the end of this era (Roser 2013). Meeting this increasing food demand, food production must increase significantly and potentially double by 2050 (Hunter et al. 2017; Steinwand and Ronald 2020). Between 1985 and 2005, the total worldwide crop production increased by only 28% which seems to fall short of the expected demands (Foley et al. 2011). Geographical regions and suitable technologies have to be identified for non-incremental increase in food production (Ray et al. 2012).

The Green Revolution (GR) of the 1960s provided an enormous amount of food security with widespread cultivation of high-yielding varieties of staple crops (Steinwand and Ronald 2020; Pingali 2012). With quick advancement in genome sequencing innovations and gene editing tools, new entryways for accomplishing the 2nd Green Revolution can be seen.

Plants are manifested with trillions of microbes in nature, which colonize and inhabit various spaces or compartments of the plant and are thus considered a second genome of the plant (Kumar et al. 2016). These include rhizosphere, rhizoplane, endosphere, and phyllosphere. The effective communication between plant and microbiota establishes a successful relationship between microbial communities and plants. Based on beneficial and harmful associations, PM interactions can be known as amensalism, antagonism, commensalism, mutualism, neutralism, and competitive by nature. Phyllospheric microorganisms, which are exposed to low humidity and high irradiation, aid in the defense of plants from airborne pathogens, while the rhizosphere of plants is a nutrient-rich region that encourages the growth of soil microorganisms (Kumar et al. 2016). Characterization of such PM interactions indeed has improved agricultural productivity (Jackson and Taylorbi 1996). Studying the molecular aspects of PM interactions at the genomic level will be a critical approach towards better utilisation of the metagenome in agriculture (Shelake et al. 2019a). For the large-scale validation of these interactions, bio-informatic approaches and in-silico methods are needed with modern methodologies such as omics approaches for providing insights into PM interactions (Kumar et al. 2016; Shelake et al. 2019a).

With quick advancement in sequencing tools, availability of genomic data of various plant species, and genome altering frameworks, the chance to alter genes and create cultivars with expanded flexibility, yield, and quality is progressing at a rapid pace (Chen et al. 2019). Sequence-specific nucleases including mega nucleases, zinc-finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) have been demonstrated to be viable for plant genome altering, however, a number of drawbacks restrict their application (Zhu et al. 2020). Recently developed prokaryotic CRISPR–Cas system has transformed the gene-editing field with high efficiency and easy application. CRISPR stands for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat. It is made out of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) (transcribed from the spacer sequences) and transactivating crRNA, or single chimeric guide RNA (sgRNA) (formed by the fusion of crRNA and trancrRNA) for direction and targeting specificity (Brouns et al. 2008). The Cas9 protein–RNA complex is formed by the combinations of the spacer of the crRNA to a target sequence which is close to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (Adli 2018). The Cas9 protein–RNA complex cuts the target nucleic acid. The site-specific cleavage at a genomic location harbouring a PAM can be accomplished by targeting CRISPR–Cas frameworks with crRNAs with a suitable spacer (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach 2019). However, many new CRISPR–Cas systems have been developed which has widened the range of applications of this novel genome engineering tool (Church et al. 2013).

In this review, we discuss the rapidly emerging applications of the CRISPR–Cas genome engineering tool to better understand PM interactions for better crop production which can lead the path to Green Revolution 2.0 to meet the food demand of dramatically increasing world population.

First Green Revolution: its impact on society

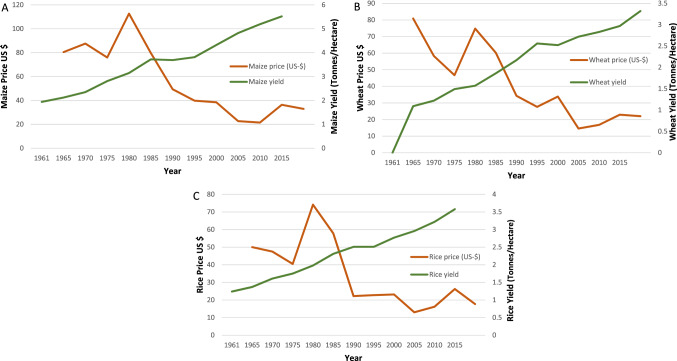

Institutions like International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) in Mexico, and International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines took the step forward towards the declining crop production and successfully developed improved high yielding varieties of major staple crops such as wheat, maize, and rice, respectively (Pingali 2012). This crucial step led to the first Green Revolution (1966–1985) and impacted the global food production with significant increase in wheat, rice, maize, sorghum and millets. Simultaneously, cereal consumption also increased by 150% in several Asian countries during 1965–1990 (Evenson and Gollin 2003; Khush 2001). This GR exhibited a positive impact on socio-economic conditions as well as on environmental sustainability. Approval of high-yielding varieties has helped most of the high populated countries to meet the surging food demand without opening up new croplands. If traditional varieties were used to produce the harvest yields of 1960, most of the woodlands, forests, and mountainsides would have disappeared. The per capita increase in the availability of significant staple crops (rice, maize, and wheat) resulted in a decline in their cost of production which granted a significant decrease in their true prices in international as well as domestic markets (Fig. 1). The unit production costs and prices of high-yielding varieties of rice, wheat, and maize was about 20–30% and 40% lower than their traditional varieties, respectively (Khush 2001).

Fig. 1.

Graphs representing impact of Green Revolution on major staple cultivars over years with respect to yield and price. A Maize, B wheat, C rice.

Adapted from Ritchie and Roser (2013), Roser and Ritchie (2013)

Variety traits that led to Green Revolution

Increased harvest index

Harvest Index refers to the aerial biomass of the plant. Plants with the largest aerial biomass were selectively bred which also displayed high photosynthetic allocations resulting in increased food portion (HI) (Yang and Zhang 2010). The Harvest index of staple crop varieties before the Green Revolution was reported to be 0.3 but these new high-yielding varieties increased it up to 60% (Khush 2001).

In rice, to increase the edible biomass, plant height was reduced by incorporating a recessive gene sd1 from a Chinese rice variety ‘Dee-Geo-Woo-Gen’ to produce dwarf rice varieties with less straw production and higher grain production (Heu et al. 1989). Whereas, in wheat, Rht1 or Rht2 genes were incorporated from Norin 10 Japanese variety for the production of dwarf varieties. The short stature of these varieties also increased the responsiveness to nitrogenous fertilizers which increased the yield to about 9 tonnes/hectare (Rauf et al. 2015).

Abiotic stress tolerance

Only 11% of the Earth’s land is fit for cultivation, the rest of the soil is highly deficient in nutrition with various other discrepancies. Large rice and wheat growing lands are facing nutritional deficiency, drought, salinity, toxicity, etc. Thus, different improved varieties were created through selective breeding to have moderate to significant degrees of tolerance for several toxicities and nutritional deficiencies.

Biotic stress resistance

High-yielding varieties readily replaced many traditional varieties because of their short duration, photoperiod insensitive traits which expanded their production period to a full year and led to amplified disease incidence and insect numbers. The use of fertilizers and pesticides over a whole year is impractical and uneconomical. This concern fascinated the researchers to develop multiple disease-resistant varieties. Some of the major diseases that hindered healthy growth and lowered the crop yield were grassy stunt, bacterial blight, green leafhopper, gall midge, and blast. The first variety of rice with multiple disease resistance was IR26 (Khush 2001). Similarly, wheat and maize varieties have also been developed with multiple disease resistance such as stem rust, stripe rust, Septoria leaf rust, Fusarium head scab, and leaf blotch (Gupta et al. 2010).

Wide seasonal adaption

Due to the photoperiod sensitivity of many traditional varieties, their yield was restricted to only one season. However, improved rice varieties like IR8 (released in 1966) were incorporated with the se1 gene (photoperiod insensitivity) and made it suitable for growth during any season. Hence, IR8 was known as ‘Miracle Rice’ and was grown in many rice-growing countries such as Africa, Asia, Latin America (International Rice Research Institute 1982; Khush 2001). Similarly, wheat varieties were made photoperiod insensitive by incorporating Pdp1 and Pdp2 genes (Rauf et al. 2015).

Short growth duration

This trait played a crucial role in increasing farm employment, cropping intensity, food supplies, and also increased food security in many countries. IR8 variety of rice matured in only 130 days as compared to traditional varieties which took about 170 days to mature (Khush 1995). Traditional varieties were also photoperiod sensitive which restricted their production to only one season. Short growth duration varieties produce the same amount of biomass in 110–115 days as the traditional varieties in 130–135 days.

Negative side of the success of GR

Despite the success of the GR, it still had its boundaries. Surely, it led to many hectares of land to be converted into agricultural lands and also avoided hunger for millions of people but also brought a few consequences with it. First, GR was based on a strategy to intensify the crop yield in favourable areas. But areas under low marginal environmental value faced less or even no benefit from the GR and led to relatively lower poverty reduction (Pingali 2012). The impact of agricultural development on food security and agricultural productivity in Asia to 1% increase in crop productivity and 0.48% poverty reduction. In India, a 1% increase in agricultural value and 0.4% poverty reduction was seen in the short run and 1.9% in the long run.

During the GR, owners of large plantation fields benefitted the most as they adopted the new advancements because of their better access to the water system (high yielding varieties were better cultivated in rain-fed areas), composts, seeds, and funds. Small farmland owners were the least benefitted, because the Green Revolution brought about lower item costs, higher input costs, and endeavours of property managers to raise rents or power inhabitants from the land. Also, GR encouraged mechanization, thereby pushing down rural wages and employment (Pingali 2012).

The GR was broadly criticized for causing ecological harm. Extreme and improper use of fertilizers and pesticides has contaminated streams, poisoned farmers, and killed useful bugs and other natural life. The water system resulted in the salt build-up and eventual deserting of probably the best cultivating lands (Pingali 2012). Groundwater levels were reduced in zones where more water is being pumped than can be recharged by rain and heavy reliance on a few significant cereal varieties resulted in the loss of biodiversity on farmlands. A portion of these results was unavoidable as many ignorant farmers started to utilize excessive water and fertilizers due to subsidy policies which resulted in negative natural impacts.

Green Revolution 2.0

Global population is expected to rise by nearly one-third by 2050, necessitating a 70% increase in food production. GR 2.0 must continue to work on changing the yield frontier for the primary staples to meet this need. Increased cereal production diversified the lands for high-value crops. In addition to increasing cereal output, GR 2.0 is required to confer crop resistance to abiotic and biotic stress. Improved drought- and submergence-tolerant cultivars boost smallholder productivity in marginal areas and give them tools to adapt to climate change. Taking into account a variety of factors (global population growth, climatic changes, biotic and abiotic pressures), researchers began to focus on improving plant health in recent years by expanding their knowledge of plant-associated beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms. Microbial interactions have an important role in the long-term viability of various habitats. Understanding the connections and basics of microbial networks requires a thorough understanding of such cooperation between bacteria and other biotic and abiotic factors, which are now been provided by highly efficient GE tools. In this genomic era, our ability to discover and modify the genetic elements that underpin complex traits will be critical for designing crops that are resistant to such pressures. This is where CRISPR–Cas approach has immense potential, a recently developed adaptive immune response which is highly efficient in terms of generating crops that are more resistant to various stressors. Generating such resistant cultivars will probably solve the upcoming surge of food demand with rapidly growing global population and changing climatic conditions.

Plant–microbe interactions

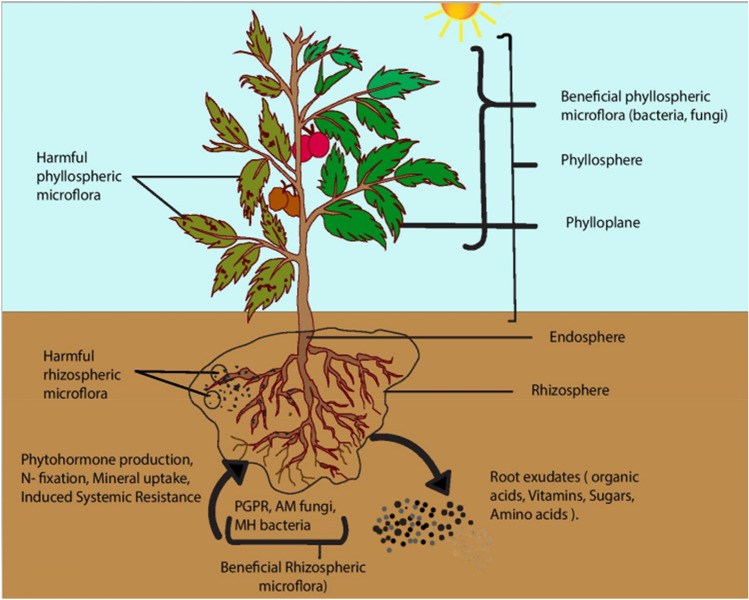

Microbial interactions have an explicit part in the sustainability of different environments. Microbes interact among themselves, with soil and host (plant). Among these interactions, plant–microbe interactions play a significant part to regulate biological systems. Plants produce various natural compounds which help in the colonization of a variety of organisms (Kumar et al. 2016). Based on the areas of microbe interactions onto plants, microbes can be characterized into two groups, phyllosphere microorganisms (in communication with aerial parts of plants), and rhizospheric microorganisms which associate with the rhizosphere of plants (Fig. 2). Phyllospheric microorganisms survive under variable climate assisting plants in their overall growth and development. The rhizosphere of plants is a nutritionally rich zone because of compounds such as organic acids, vitamins, sugars, amino acids, etc. produced by the roots. Diverse microorganisms communicate with various plant tissues or cells with different degrees of dependency.

Fig. 2.

Beneficial and harmful bacteria in phyllosphere and rhizosphere. The aerial and root part of the plant represents the phyllosphere and rhizosphere, respectively. The phyllosphere and rhizosphere produce a variety of secondary metabolites and exudates that operate as a defence mechanism for the plant against pathogenic microorganisms while also influencing the assembly of helpful bacteria by functioning as a chemoattractant which result in a healthier plant

Plant–microorganism interactions modulate soil carbon sequestration by the modification of the terrestrial carbon cycle (Shelake et al. 2019b; Cavicchioli et al. 2019). In under-nourished conditions nitrogen and phosphorus reach plants via symbiotic consortium of N-fixing rhizobia with legumes and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), respectively, which independently falls under beneficial PM interactions. (Cao et al. 2017; Shelake et al. 2019b). Symbiotic conduct helps PGP (Plant Growth Promoting) microorganisms to overpower the number of inhabitants of other microbial species. Numerous PGP microscopic organisms influence plant development through the production of phytohormones such as gibberellin, cytokinin, and auxin and plant-helpful catalysts such as ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase). Some PM associations are valuable under heavy metal stress as these microbes help plants in the removal of heavy metals from contaminated soil (Shelake et al. 2018).

Diversity of beneficial microbes in phyllosphere and rhizosphere

The rhizosphere harbors a wide assortment of bacterial species, and the arrangements of bacterial networks vary as indicated by root zone, plant species, plant phenological stage, stress, and disease events (Miransari 2013). A significant bacterial assembly in the rhizosphere is characterized as PGPR, which can advance the development, supplement take-up, and microorganism biocontrol in plants (Mendes et al. 2011). The most governing consortium of bacteria which possibly can advance plant growth and development are Actinobacteria (11%), Firmicutes (18%), Proteobacteria variants [Alpha-proteobacteria, Beta-proteobacteria, Gamma-proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes] (46%), Acidobacteria (3%) and especially the genera Rhizobium, Azospirillum, Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacter. The most common rhizospheric bacterial group is Proteobacteria because of their capacity to react to labile C sources, expressing quick development and variation to the different plant rhizospheric microbes (Chaparro et al. 2013). Proteobacteria are followed by Acidobacteria, which have been credited a significant job in the C cycle in soils because of their capacity to reduce cellulose and lignin. Actinobacteria have been shown to be part of soils which have relatively higher disease suppression abilities and enhance root nodulation and plant growth and development (Mendes et al. 2011; Lagos et al. 2015).

Factors influencing the assembly of microbes (beneficial and pathogenic)

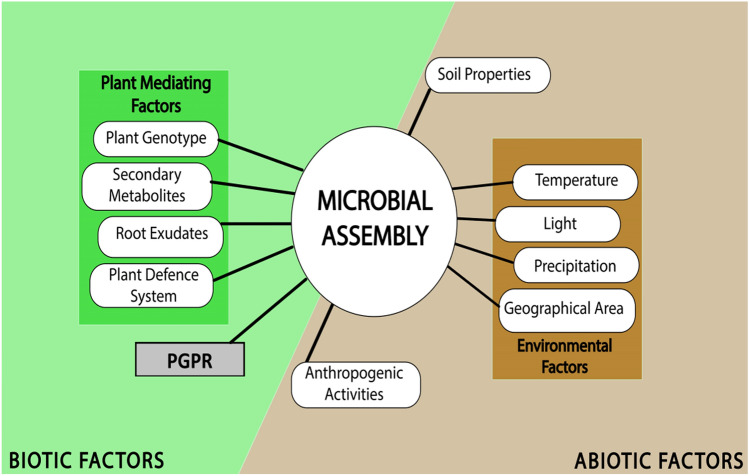

Major factors that define the assembly of microbes are Environment, Soil, and Plant-mediated factors (Fig. 3). The major plant-mediated factors include genotype, immune system, metabolite secretion, and root exudates, which govern the composition and structure of the microbial community. Plant genotype governs and regulates the metabolites and exudates secreted by the roots and plant, respectively. Plant metabolites, for example, coumarins influence the host microbiota, the assembly of root microbiome, and act as semi-synthetic substances in PM connections (Stringlis et al. 2019). PRR (Pattern Recognition Receptors) in plant immunity are thought to door microbial passage into leaf tissues, and adequately prevent the colonization of non-adapted strains. Intracellular receptors like Nod-like receptors (NLR) (Leucine-rich repeats) are very diverse and helps with stimulation of strain-specific protection from host-adapted pathogens (Chaudhry et al. 2021). Beneficial microbial species are abundant in the rhizosphere as well as phyllosphere because of positive and selective plant pressure. Anthropogenic factors like higher dosage of fertilizers and pesticides and pollution deteriorate air, soil, and water quality leading to suboptimal PM interactions (Castrillo et al. 2017). Soil properties, for example, soil pH, soil type, macronutrient circulation, organic matter, moisture content, and salinity drive the microbial local area arrangement. Ecological factors likewise fundamentally impact the association of phyllosphere organisms that include light, environment, bright (UV) radiation, water, and geographic area. Plant genotype is the outcome of interactions between plant-associated microbiota, environmental factors, and plant genotype and the architecture of microbial communities depends on the above-mentioned factors (Shelake et al. 2019a). Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) confers protection to a wide range of pathogens. A number of bacterial species belonging to Bacillus, Pseudomonas and others enhance the immune response of plants (Pieterse et al. 2014).

Fig. 3.

Factors influencing the microbial assembly for beneficial plant–microbe interactions. These include abiotic and biotic factors. Abiotic factors are associated with environmental factors, soil and others. Biotic factors include plant- and PGPR-associated factors

Underlying mechanism associated with the PM interactions

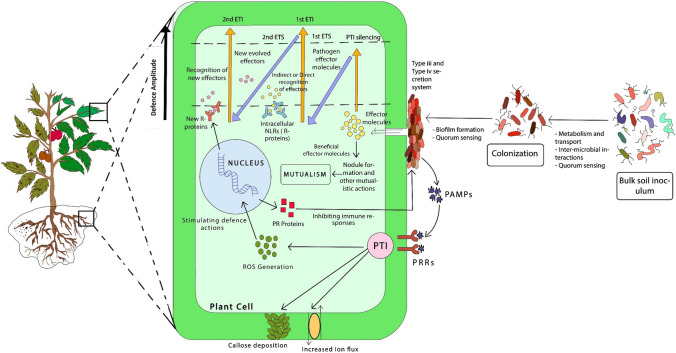

Various complex plant–microbe and microbe–microbe interactions are needed for the selective assembly of plant-associated microbiomes. Plants interact with the microbiome through the root exudates. The microorganisms in the environment vary in their genomic potential to degrade, metabolize and utilize diverse metabolite substrates released by plants (Fig. 4). Diverse bacterial groups produce specific chemicals for signaling and communication. These include the production of N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone (AHL) and quinolones by Gram-negative bacteria and (Taga and Bassler 2003; Lv et al. 2012). AHL is used as a signaling molecule for leaf–microbe interactions (Enya et al. 2007). Chemotaxis, motor proteins and aggregation of flagella leads to the formation of microbial communities over plant surfaces followed by colonization through exudates interchanges between plants and microbial groups, governing the development as well as construction of biofilms. Various two, three or multi-component sensing and monitory microbial pathways are associated with the incorporated and facilitated modulation of biofilm formation. Intra-microbial and inter-microbial communications amongst diverse species is facilitated either by two-component systems or quorum sensing. Initiation of biofilm formation is mediated by a 2º messenger (c-di-AMP) which regulates the inter-microbial cell interaction as well as genes expressed in biofilm construction. After reaching a threshold microbial density, biofilms start acting in harmony leading to quorum sensing, thereby producing specific compounds that enhance plant growth and development (McNear 2013). Furthermore, the entry into plant tissues is enabled by the release of lytic enzymes. Beneficial microbiota produce lytic enzymes and effector proteins (via type 3 and type 4 secretion systems) in low concentrations as compared with pathogens, thereby preventing the activation of plant immune responses.

Fig. 4.

The bulk soil microorganisms serve as “seed banks”, with varying genetic ability to digest, use, and metabolise various metabolite substrates. Two-component systems and QS are critical for both inter-microbial and intra-microbial communications, leading to colonisation and biofilm formation. Lytic enzymes, such as lysozymes or cell-wall destroying enzymes, facilitate entry into plant tissues. Symbionts, unlike infections, are thought to release minimal quantities of lytic enzymes, and type 3 and type 4 secretion systems that deliver effector proteins, avoiding stimulation of plant immune response leading to mutualism. This characteristic isolates them from pathogenic infection systems. Pattern triggered immunity (PTI) and viral dsRNA are stimulated in phase 1 to silence the viral RNA genes. In phase 2, the PTI and silencing is disrupted giving rise to 1st ETS. In phase 3 activated 1st ETI is an intensified variant of PTI that frequently overcomes the hypersensitive response and apoptosis. In phase 4, the pathogens try to recover the suppressed ETI by generating modified effector molecules, this gives rise to 2nd ETI. On the other side, ROS are also generated to trigger the defence actions followed by the production of PR (Pathogenesis Related) proteins that further promotes inhibitory immunological responses by directly acting on pathogens. [PTI + Silencing – ETS + ETI] determines the eventual amplitude of disease resistance or vulnerability.

Adapted from Zvereva and Pooggin 2012; Singh et al. 2019; Trivedi et al. 2020

The new molecular methodologies discovered almost negligible difference between pathogens and symbionts. Hence, beneficial microbiota act as “intelligent pathogens.” This was proved by comprehensive transcriptional analysis of Lotus japonicus (D’Antuono et al. 2008; Deguchi et al. 2007) and Medicago truncatula (Jones et al. 2008; Lohar et al. 2006) (Djordjevic et al. 2003). The microbial genes encoding Type III and Type IV secretion systems enable transport of effector molecules from the microbial cytoplasm to the plant cytoplasm resulting into either mutualism or pathogenesis (Singh et al. 2019). According to the Zig-Zag model of plant–pathogen interaction proposed by Jones and Dangl (2006), plant–microbe reactions are mediated when conserved PAMPs are detected by PRRs which stimulate Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI). Signaling downstream of PRRs includes Ca2+ influx, MAP-K pathway, and production of extracellular ROS by NADPH oxidase. In the meantime, microbes release effector proteins and molecules to the plant. Effector proteins released by pathogens that are adapted to plants interfere with the PTI [1st level of effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS)]. Adapted effector proteins might manipulate the immunity signaling components of the plant; therefore, plants have evolved a second class of receptor molecules to monitor the intracellular effector molecules, i.e., NLR receptors (R proteins). Indirect or direct recognition of effector molecules by intracellular NLR receptors activates the receptors giving rise to 2nd level effector-triggered immunity (ETI). To overcome 2nd ETI, the pathogens either change or eliminate the recognized effector or derive another effector molecules that suppresses the ETI, leading to 2nd level of effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS). ETI and PTI comprise dramatic transcriptional reprogramming and include increased expression levels of defense genes encoding enzymes, signalling hormones and antimicrobial proteins for the biosynthesis of antimicrobial secondary metabolites (Jonesand Dangl 2006). ETI commonly results in a programmed cell death response called as Hypersensitive Reaction (HR) (Hatsugai et al. 2017). The PR (Pathogenesis Related) proteins shield the plants from further infection by accumulating locally in the nearby uninfected tissues as well as distant uninfected tissues (Jain and Khurana 2018).

A significant role of small RNAs was first discovered for plant development and advancement (Mallory 2006). There is intensifying proof, that small RNAs are engaged with managing plant responses to adverse conditions, as well as biotic stresses (Padmanabhan et al. 2009). Antiviral defenses including virus-derived small RNAs (making them exogenous in origin) intervenes the plant and pathogen interactions developing a type of plant defence system. Unlike viruses that duplicate inside the host cell through replication and transcription, bacteria, fungi and, parasites, and different microorganisms interact directly with plants without multiplying inside the plant cell. Host endogenous small RNAs (miRNAs and siRNAs) play a significant part in balancing these microbes in establishing a plant immunity framework against pathogens (Katiyar-Agarwal and Jin 2010).

Approaches to analyze PM interactions

In silico methodology

Systems biology (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics) and molecular modelling approach help to understand the microbial enzymes and proteins involved in PM interactions. In-silico transcriptomic study of both host and microbe enables us to understand the changes occurring during these interactions. The time-dependent variation in metabolite concentrations and signaling processes are calculated via differential equations for the analysis of biochemical processes in metabolic kinetics studies. The study of unique interactions is complex, because examining even a small dynamic behaviour requires many parameters and data as well as several dimensional overviews (Kumar et al. 2016).

Holo-omics approach

To accomplish a more coordinated insight into plant–microbiome relations, the experimental design which pairs omics methodologies (for example, metabolomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics) with more frequently utilized microbial centred procedures (for example, amplicon sequencing, meta-genomic, meta-transcriptomics, and exo-metabolomic). The term "holo-omics" portrays analysis of host and microbial datasets which provide a powerful approach for developing hypothesis and advancement in the area (Nyholm et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2021). Holo-omics study includes three major stages i.e., Design, Analysis and, Validation. The design includes a longitudinal sampling process, selection of sample types, and evaluation of optimal data types to address the scientific questions in the study. Analysis of the approach includes selecting the appropriate range of technical and biological expertise and also the selection of appropriate tools and analytical framework for incorporation of diverse data types. Design and analysis help to form a downstream hypothesis which can be validated by the use of techniques for the modification of host genotype as well as direct manipulation of microbial genetic space. This gathered information is then finalized with the bottom-up approach to construct synthetic communities (Xu et al. 2021). A number of studies conducted involving plant–microbe interactions are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Holo-omics approach reveals association of different microbes with plants

| Phylum | Site of Association | Host Plant | Method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microflora (Phyllosphere) | |||||

| Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria | Bacteria | Phylloplane | Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), and Neotropical Forest and Poplar trees | Next-generation sequencing, culture-independent and culture-dependent methods based on taxonomic markers | Oliveira et al. (2012) |

| Actinobacteria, Alpha-, Beta-, Gammaproteo-bacteria, and Sphingo-bacteria | Tropical tree | Kembel et al. (2014) | |||

| Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes | Phylloplane and Rhizosphere | A. thaliana | Ulrich et al. (2020) | ||

| Methylobacterium and Sphingomonas species | Phylloplane | A. thaliana, B. Trifolium repens, and Glycine max | 16S rRNA, ammonia oxidation (amoA), and nitrogen fixation (nifH) gene markers | Delmotte et al. (2009) | |

| Methylobacterium, Kineococcus, Sphingomonas, and Hymenobacter | Poplar trees | Durand et al. (2018) | |||

| Erwinia herbicola | Beta vulgaris | Thompson et al. (1993) | |||

| Dothideomycetes and Eurotiomycetes | Filamentous fungi | Mussaenda pubescens | Qian et al. (2018) | ||

| Dothideomycetes and Tremellomycetes | [Mangrove’s ecosystem] Aegiceras corniculatum, | Yao et al. (2019) | |||

| Avicennia marina, | |||||

| Bruguiera gymnorrhiza, | |||||

| Kandelia candel, | |||||

| Rhizophora stylosa, and Excoecaria agallocha | |||||

| Cladosporium and Alternaria | Beta vulgaris | Thompson et al. (1993) | |||

| Protomyces, Dioszegia Leucosporidium, and Rhodotorula | Yeast | A. thaliana | culture-independent | Agler et al. (2016) | |

| Olletotrichum, | Phylloplane and Caulosphere | Catharanthus roseus | Dhayanithy et al. (2019) | ||

| Alternaria, and Chaetomium Genus | |||||

| Cryptococcus and Sporobolomyces yeasts, and Pseudomonas sp. | Phylloplane | Beta vulgaris | Thompson et al. (1993) | ||

| Rhodotorula glutinis and Sporobolomyces roseus | Oxalis acetosella L | Glushakova and Chernov (2004) | |||

| Microflora (Rhizosphere) | |||||

| Achromobacter, Clostridia, Cellulomonas, Bacillus, Gallionella, Herbaspirillum, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Xanthomonas, Sinorhizobium, Burkholderia, Pantoea, Enterobacter, Geobacter, Stenotrophomonas, Nocardia, Mycobacterium, Microbacterium | Bacteria | Rhizosphere | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | 16S rRNA | Chaparro et al. (2013) |

| Acidobacteria, Gemmatimonas Rhodoferax | Maize (Zea mays L.) | 16S rRNA variable gene (V4–V5) | Correa-Galeote et al. (2016) | ||

| Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteriodetes | Endosphere | Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis) | Akinsanya et al. (2015) | ||

| Geodermatophilus, Actinokineospora, Actinoplanes, Streptomyces, Kocuria | Rice (Oryza sativa) | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Mahyarudin et al. (2015) | ||

| Bacillus, Bradyrhizobium rhizobium, Stenotrophomonas, Streptomyces | Rhizosphere | Soybean (Glycine max) | |||

| Alkanindiges, Sphingomonas, Burkholderia, Novosphingobium, Sphingobium | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | Schreiter et al. (2014) | |||

| Arthrobacter, Kineosporiaceae, Flavobacterium, Massilia, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes | Rhizosphere, Endosphere and Rhizoplane | Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale cress) | Bodenhausen et al. (2013), Bulgarelli et al. (2012) | ||

| Acidobacteria, Proteobacteria | Rhizosphere, Endosphere | Populus deltoides (Poplar) | Gottel et al. (2011) | ||

| Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Pantoea, Klebsiella, Erwinia, Brevibacillus, Staphylococcus, Curtobacterium, Pseudomonas sp. | Endosphere | Sugarcane | Magnani et al. (2010) |

Gene editing approach

Targeted genetic modifications have opened a new gateway of opportunities towards improving crop characters and enhancing the yield as well as providing resistance to abiotic and abiotic stress. Three mega nucleases like Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFN), Transcription Activator- like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and CRISPR–Cas system introduce double strand breaks in the target DNA sequence which are then repaired by Homology directed Repair (HDR) and Non-Homologous end Joining (NHEJ) (Kumar et al. 2016; Symington and Gautier 2011). ZFNs consist of two DNA binding domains, first domain contains eukaryotic transcription factor and a zinc finger, the second domain consist of FokI restriction enzyme which acts on targeted DNA sequences. TALENs slice the targeted DNA sequence using TALE effector DNA binding domains. The target DNA sequence requirement is a match with the di-amino acid sequence in ∼33–35 amino acid conserved target sequence. TALENs were discovered during the study of bacteria Xanthomonas genus (Nemudryi et al. 2014). After the discovery of TALEN, CRISPR gene editing tool was also discovered in Escherichia coli. CRISPR–Cas system is a unique mechanism which protects microorganisms from foreign DNA penetration. Complex of Cas proteins and non-coding RNA elements of CRISPR interacts with the target site through complementary sequences.

ZFN-based technology has various disadvantages: complexity and high cost of constructing protein domains for each specific genomic locus and a higher rate of inaccurate target DNA cleavage. Larger size of cDNA encoding TALEN (around 3 kb) marks a significant disadvantage for TALEN associated gene editing. In principle, compared with ZFN, it is relatively more difficult to deliver and express a pair of TALENs in cells thereby making them less efficient and attractive for therapeutic applications where they have to be delivered in viral vectors with limited RNA molecules. Moreover, the high repetitiveness of TALENs may affect their ability to be packaged and delivered by some viral vectors, although it is possible to overcome this difficulty by diversifying the coding sequence of TALE repeats (Gupta and Musunuru 2014; Holkers et al. 2013) These disadvantages attracted many researchers worldwide to develop a framework to overcome these problems. And hence, the limitations were overruled by CRISPR Cas system. Variations of 20 bp spacer prototype of guide RNA helps CRISPR Cas complex to adapt to any RNA sequence in the genome. Distinct gRNAs are been made and delivered by subcloning the nucleotide stretch into the backbone of gRNA plasmid. This was a crucial approach to produce large number of vectors targeting genomic locations as well as genomic libraries simultaneously (Zhou et al. 2014). This marked as a significant advantage over ZFNs and TALENs. The composition of the Cas9 protein remains unchanged. The highest efficiency among gene editing tools was reported for CRISPR–Cas9 (81%) compared to TALENs (76%) and ZFNs (12%) (Chen et al. 2014).

The Novel CRISPR–Cas system

As early as 1987, the novel CRISPR–Cas system was discovered in Escherichia coli genome (Ishino et al. 1987), but its biological function was only reported in 2007 (Barrangou et al. 2007). CRISPR–Cas is an adaptive immune response against foreign plasmids and phages is now reclassified into five types i.e., I-V. Host captures a 20 nucleotide DNA stretch from the invading plasmid known as spacer and integrates it in between CRISPR locus in the first invasion (Nuñez et al. 2015). CRISPR along with the spacer sequence forms CRISPR RNA (crRNA) via transcription. CrRNA in association with trans-activator CRISPR RNA (trancrRNA) forms gRNA. An R-loop assembly is formed when Cas nuclease (guided by gRNA) reaches the homologous site. Complex of tracrRNA and Cas nuclease induces a double strand break on DNA upstream of the PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif). HNH and RuvC domains of Cas nuclease helps in generating a double stranded break (Heler et al. 2015). Type of CRISPR–Cas determines the spacer and PAM necessity (Xue et al. 2015). In the commonly utilised type II CRISPR–Cas9 framework, the last 12 ribonucleotides (known to be the seed sequence) at the end of the 3´ RNA spacer determine the specificity of the complementary target. It is believed that the dislocation at the 5´ ends of gRNA-Cas9 is tolerable during the process of binding to the target. However, it turns out that the interface of this region with the distal PAM sequence is necessary to trigger the action of the Cas9 endonuclease. The PAM sequence is a 2–5 bp motif required for spacer attainment and cleavage of target (Barakate and Stephens 2016; Shah et al. 2013).

Evolution of CRISPR frameworks

Cas proteins can be characterised into four discrete functional modules: adaptation (spacer acquisition); interference (target cleavage); ancillary (regulatory and other CRISPR-associated functions); expression (crRNA processing and target binding) (Makarova et al. 2015). Based on the Genes encoding Cas nucleases and the nature of the interfering complex, the CRISPR–Cas system has been characterised into two classes and by the virtue of its characteristics, Cas genes are further divided into six types. CRISPR Cas class 1 systems (type I, III, IV) use multiple Cas protein complexes (Cas3, Cas5, Cas8, Cas10 and Cas11) in multiple groupings for interference, while class 2 systems (type II, V, VI) produce interference with unique and single effector protein (Cas9 orthologues, Cas12 or, Cas13) in association with CRISPR RNA (crRNA) (Makarova et al. 2020). According to 2015 classification scheme, 2 classes, 5 types and 16 subtypes were known, but according to the updated 2020 scheme, 4 more subtypes were added. Principle of genome editing with CRISPR–Cas9 is based upon RNA guided interference with DNA (Koonin et al. 2017).

The most popular type of CRISPR–Cas system in nature is the type I system, which consists of a multimeric DNA-targeting complex called ‘Cascade' and the endonuclease Cas3. Cascade must first bind to DNA through PAM and spacer recognition before recruiting Cas3 to a target DNA sequence. Cascade has a wider range of target sites due to its promiscuous identification of PAM sequences. Cas3 recruitment causes a single-stranded nick in the target DNA, which is then degraded by 3–5 exonuclease actions. Cas3´s nickase and helicase activities are both required for the degradation of foreign DNA in prokaryotes. Cas3´s specific cutting mechanism is used as an antimicrobial weapon, with endogenous or exogenous type I systems guided towards bacterial genomes for degradation and apoptosis. Cas3´s nickase, helicase, and exonuclease activities may be repurposed for new applications in mammalian cells (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach 2019).

A single large Cas9 protein is involved in type II systems. Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) was the first ever protein to be used in vitro and reprogrammed for gene editing in eukaryotic cells. It consists of two components i.e., sgRNA (complex of crRNA and trancrRNA) and, Cas9 nuclease. 20 bp long sequence at the 5´ end of sgRNA guides the above complex towards the target site for interference of similar DNA sequence adjacent to 5´-NGG-3´ (N = any nucleotide) of PAM sequence (Chen et al. 2019). Signature nuclease domains HNH and RuvC of Cas9 protein cleave the targeted non-complementary and complementary DNA sequences, respectively, by generating a blunt double stranded break (DSB). Aspartate to alanine substitution (D10A) and histidine to alanine substitution (H840A) in the RuvC and HNH catalytic domains, respectively, generates nCas9 (Cas9 nickase) to cleave targeting and non-targeting sequences separately. When mutations are introduced in both the domains, the nuclease activity is obliterated leading to an enzymatically inactive dCas9 that could also nonetheless aim specific genomic loci and act a scaffold for engaging effector proteins (Chen et al. 2019; Jiang and Doudna 2017). To increase the opportunity of target specificity, few other Cas9 orthologues were discovered.

Since Cas9 is able to cleave ssDNA, it can also target a specific RNA in a similar manner by designing PAMs specific for RNA sequences that are absent on corresponding genomic DNA sites. This RNA targeting system is known as RCas9. Endogenous RNA can be detected by directing dCas9 to RNA. Catalytically active RCas9 can stimulate targeted ssRNA cleavage. Therefore, cellular processes at molecular level can be regulated by RCas9. Via DNA targeting expression of toxic RNAs can also be blocked (O’Connell et al. 2014).

CRISPR Cas12a formerly known as Cpf1 is a Class II RNA-guided endonuclease which belongs to type V system. Cpf1 makes a staggered cut with a 5 nucleotide 5 overhang at selected DNA sites starting at 18 nucleotide 3´ of T rich PAM (Chen et al. 2019). In comparison to Cas9’s blunt end formation, staggered end cuts may be more useful in some applications (for ex. incorporation of DNA sequences in specific alignment and position.). Cas12a can also modify crRNA arrays to produce its own customised crRNAs which will help in multiplexed genome editing with multiple crRNAs (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach 2019). Cms1 (CRISPR from Microgenomates and Smithella) is another group of class 2 type V enzyme that efficiently generates indel mutations in rice. In comparison with Cas9 and Cpf1, Cms1 nucleases are smaller and require an AT-rich PAM site, and do not need a transactivating crRNA. Recent discovery on type V-B system has been made that Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus (AaCas12b) has been modified to engineer mammalian genomes. Nuclease activity of AaCas12b is applicable over wide temperature range (31–59 °C) (Zhang et al. 2019).

Cas13a previously known as C2c2 is an RNA targeting endonuclease that belongs to class 2 type VI CRISPR protein family (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach 2019). Cas13a has been designed to cleave specific mRNAs in bacteria and eukaryotic cells C2c2 is directed by a single crRNA and uses its HEPN domains to cleave single-stranded RNA targets with complementary protospacers. C2c2's HEPN domains are required for crRNA-guided ssRNA cleavage but not binding (Abudayyeh et al. 2016). dCas13a has been targeted to mRNA after stimulation by ssRNA targets, similar to RCas9, to visualise the formation of stress granules. Cas13a cleaves uracil bases in its immediate vicinity, and this ‘collateral' cleavage also affects adjacent, untargeted DNA. In vitro, with purified Cas13a RNAs, the collateral cleavage observed following programmed mRNA targeting in bacterial cells was also demonstrated. This promiscuous RNase activity, which is induced when a target is recognised, has been used to create the ‘SHERLOCK' molecular detection platform (specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking). A modified version of this platform (SHERLOCKV2) has high sensitivity towards detecting targets and can detect up to 4 targets simultaneously. In both bacteria and eukaryotic cells, Cas13a has been programmed to cleave unique mRNAs (Abudayyeh et al. 2017). The fusion of dCas13 with adenosine deaminase acting on RNA resulted in a single-base RNA editing application in eukaryotic cells, this method is known as REPAIR (RNA editing for programmable A to I replacement). dCas13 can also fuse with other RNA editing domains, such as that of APOBEC1, to extend the base conversions possible with REPAIR, such as cytidine-to-uridine editing (Nishikura 2010). The discovery of a class 2 type VI-D CRISPR effector known as ‘Cas13d' was made after scanning bacterial genome sequences. Cas13d-mediated cleavage facilitates collateral RNA cleavage in bacteria, but not in mammalian cells, similar to Cas13a-mediated cleavage. Cas13d does not require the PFS (Protospacer Flanking Site) to recognise RNA (Konermann et al. 2018). Various Cas variants and sub-variants, their recognising PAM sequences and their use for gene editing are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cas variants and sub-variants along with corresponding PAM sequences

| Recognising PAM sequences | Notes | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cas9 Orthologues |

|||

| Streptococcus thermophilus | |||

| St1Cas9, St3Cas9 | NNAGAAW |

Edit plant genomes (Arabidopsis) Used for genome editing in mammalian systems |

Wyman et al. (2013) |

| Neisseria meningitidis | |||

| NmCas9 | NNNNGATT | Used for genome editing in mammalian systems | Esvelt et al. (2013) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| SaCas9 | NNGRRT |

Can directly cleave ssRNA in a PAM independent manner and crRNA dependent manner Demonstrated in rice, Arabidopsis and, citrus |

Ran et al. (2015) |

| Campylobacter jejuni | |||

| CjCas9 | NNNVRYM | Can directly cleave ssRNA in a PAM independent manner and crRNA dependent manner | Yamada et al. (2017) |

| Streptococcus pyogenesis (VQR, EQR, VRER, QQR1) | |||

| SpCas9 | NGA, NGAG, NGCG, NAAG |

First ever protein to be used in vitro and reprogrammed for gene editing in eukaryotic cells |

Zhang et al. (2019) |

| xCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT | ||

| Francisella novivida | |||

| FnCas9 | NGG, YG |

Targets bacterial mRNA and change gene expression Repurposed to target the RNA genome of hepatitis C virus in eukaryotic cells |

Price et al. (2015) |

| Streptococcus canis | |||

| ScCas9 | NNG, NGG | ScCas9 was used in rice against SpCas9. Proved more editing efficiency than SpCas9 | Chatterjee et al. (2018) |

|

Cpf1/Cas12 Orthologues | |||

| Acidaminococcus sp. (RR; RVR) | |||

| AsCpf1 | TYCV; TATV | Altered PAM for expanding specificity | Gao et al. (2017) |

| Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | |||

| AsCas12b | VTTV, TTTT, TTCN and TATV | Maintains optimal nuclease activity over a wide temperature range (31–59 °C) | Zhang et al. (2019) |

| Lachnospiraceae bacterium (RR; RVR) | |||

| LbCpf1 | CCCC and TYCV; TATG | Altered PAM for expanding specificity | Li et al. (2018) |

| Francisella novicida (RR; RVR) | |||

| FnCas12a | TTV, TTTV and KYTV; TYCV and TCTV; TWTV | Liu et al. (2021) | |

| Moraxella bovoculi (RR; RVR) | |||

| MbCas12a | TTV and TTTV; TYCV and TCTV; TWTV | Tóth et al. (2018) | |

Mechanism

Fusion of crRNA and trancrRNA forms a single delusory guide RNA (sgRNA) which gives direction and targeting specificity to Cas proteins (Brouns et al. 2008). Formation of cas9 protein–RNA complex formed by both spacer of crRNA and PAM is a very crucial step for the CRISPR framework to work, the Cas9 protein–RNA complex cuts the target nucleic acid (Adli 2018). CrRNAs with appropriate spacer arrangements can result into site specific cleavage at any genomic location consisting of a PAM or PFS (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach 2019. The break or Damage response stimulated by Cas protein is repaired via various endogenous mechanisms. Distinctiveness of different DNA repair strategies has provided new ways of gene editing.

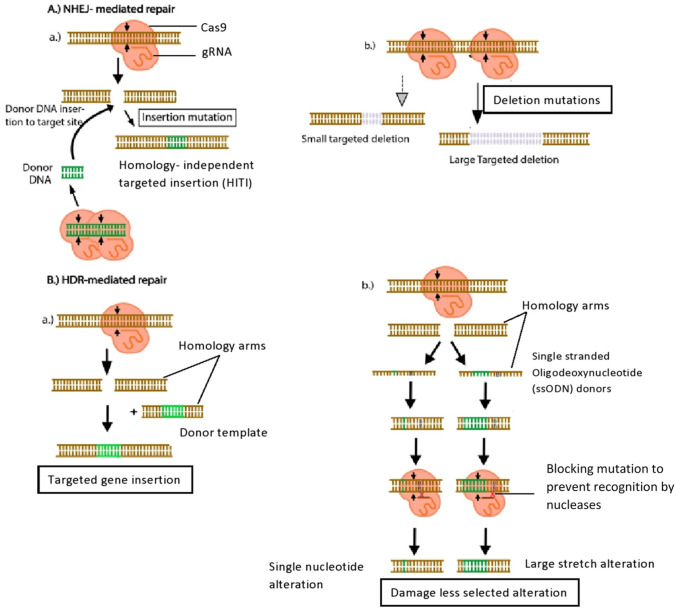

Gene editing by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)

Introducing tiny insertions or deletions at specified places in target genes has become a popular method of disrupting genes. NHEJ can be used to generate homology-independent insertions of donor DNA sequences, which could be a useful approach for gene stacking for crop improvement (Fig. 5) (Chen et al. 2019). A repair template homologous to the target site can be supplied with Cas9 to promote homology-directed repair (HDR) without any errors. However, this is often less effective than NHEJ-mediated repair. NHEJ-mediated DNA repair can be used to construct gene knockouts after Cas9 cleavage. The contrary relation between deletion size and frequency was discovered during a study of Cas9-mediated deletion efficiency, speeding up the examination of genes and genetic components (Canver et al. 2017). Gene insertion via repair mechanisms is a valuable technique for studying protein function under native biological conditions where a gene encoding an epitope tag or a fluorescent protein is inserted into target genes to monitor their proteins. When HITI (homology-independent targeted integration) uses NHEJ to repair DSBs, two issues are encountered: indels and donor integration in a random manner. Donor sequences can be flanked with homology arms to avoid these limitations (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach 2019).

Fig. 5.

DNA repair mechanisms involved in gene editing. A a Repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is error-prone and influences integration by fixing two double strand breaks brought about by Cas nuclease directing and carrying donor DNA. b Targeted deletions can be made by repairing two double-strand breaks caused by nuclease targeting two genomic locations at the same time. B a The homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway for genome editing carries homology arms to the specific site using double-stranded donor templates. b- Genome altering using single stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) is an alternative method. Silent mutations avoid resulting target site recognition by the nucleases.

Adapted from Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach (2019)

Gene editing by homology directed repair (HDR)

NHEJ does not provide the precision needed for more advanced genome engineering. HDR occurs during the cell cycle's S and G2 phases. Incorporation of desired nucleotide stretch into the target DNA and production of accurate point mutations can be accomplished by HDR-mediated genome editing. A template that is homologous to the break site is required for DSB repair. Many forms of repair templates can be used for example exogenous template, ssDNA or exogenous DNA or sister chromatids, etc. In many organisms, precise HDR-mediated genome editing is frequently used. However, because of the low efficacy of HDR and the constraints of donor template distribution in plant cells, HDR-mediated gene targeting in plants remains difficult. Multiplexed HDR in mouse embryonic stem cells produced mice with numerous precise single-point mutations (Chen et al. 2019). HDR-mediated insertion of missense gain-of-function mutations can also be used to mimic cancer in mice. Ribonucleoproteins were co-delivered with long ssDNA donors having short homology arm to construct conditional knockout mice with great efficiency by insertion of large regulatable cassettes (Platt et al. 2014). CORRECT (consecutive reguide or re-Cas steps to remove CRISPR–Cas-blocked targets) is a new HDR-dependent approach for producing scarless tailored knock-in of disease-relevant mutations (Paquet et al. 2016).

Gene editing by single base modification

Point mutations are the most common genetic variation linked to human diseases. For the establishment of genetic illness models and the development of remedial treatments, the capacity to alter single nucleotide bases is critical. Targeted HDR-mediated single-base editing can be performed by simultaneous delivery of homologous donor sequence consisting of desired nucleotide stretch and Cas9 nuclease. However, such approaches are ineffective, especially in post-mitotic cells with low HDR activity. The risk of compromised cell viability is raised because of on-target activation of DNA repair pathways. Probability of OTMs (Off target mutations) also increases in case of HDR mediated DNA repair that requires double strand breaks for modification. Few tools like VP64-dCAS9 have been developed which does not require DSBs, they use catalytically inactive dCas9 for single base modifications. Specific CT and GA nucleotides can be edited by fusion of Cas nucleases with rat APOBEC1 and lamprey cytidine deaminase 1, respectively (Komor et al. 2016). In mammalian cells, a third-generation editor (BE3) was also developed that converts 15–75% of targeted nucleotides permanently (Komor et al. 2016). BE3 was utilised to introduce nonsense mutations into the Pcsk9 gene, resulting in decreased cholesterol levels. Base editing by APOBEC3A is possible in locations with significant DNA methylation and CpG dinucleotide content. BE3 has also achieved in vivo base editing in mouse and zebrafish embryos using ribonucleoprotein-mediated protein delivery. BE3 was combined with a high-fidelity Cas9 to achieve Cas9-mediated targeting specificity (Rees et al. 2017). Fourth-generation base editors made from SpCas9 (BE4) and SaCas9 (BE5) have been developed to improve base editing by extending the linker between the hybridised proteins and adding a 2nd copy of the uracil glycosylase inhibitor (SaBE4). Adenine base editors (ABEs), which can execute selective AG (or TC) nucleotide conversions, have been added to the base editor toolset. Directed evolution and protein engineering of a tRNA adenosine deaminase resulted in a seventh-generation ABE with the greatest known editing efficiency and on-target activity. BE4max, AncBE4max, and ABEmax94 are examples of optimised and enhanced cytidine and ABEs (Koblan et al. 2018; Komor et al. 2017).

Gene expression regulation

Epigenetic editing for gene expression modifications through CRISPR provides an adaptive method to alter phenotypes to generate elite traits without changing genetic code (DNA sequences). Cas9 with endonuclease activity cleaves DNA after binding to a specific DNA sequence by the Cas9–sgRNA complex. Mutations D10A and H840A causes Cas9 nuclease to change into catalytically deficient dCas9 which lacks the endonuclease function of HNH and RuvC domains. Thereby, dCas9 only binds with targeted genomic location guided by single guide RNA (sgRNA). dCas9 leads to CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), since dCas9–sgRNA complex binds upstream of PAM sequence on the target site RNA polymerase (RNAP) activity is inhibited, and transcription is blocked (Savic et al. 2015). dCas9, in particular, is an effective tool for controlling the transcription levels of a target gene. As a result, this simple interference system known as CRISPRi allows for transient or constitutive regulation of target gene expression. CRISPRi is a better genetic engineering tool for gene knockdown in bacterial cells than RNAi (Gagarinova and Emili 2012; Nakashima et al. 2006). CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) is used to activate the expression of a gene up to three-fold by fusing dCas9 with transcription activators such as the RNAP subunit (Cho et al. 2018; Bikard et al. 2013).

Precise base editing approaches

The low editing efficiency of HDR has limited its use in plants. Alternative genome editing technologies include deaminase-mediated base editing and reverse transcriptase-mediated prime editing which does not require double strand breaks and donor DNA for repair.

Dual base editing

Successful C-T; G-A and A-G; T-C substitutions in plants can be made using cytosine and adenine dual base editor which requires only sgRNA (Li et al. 2020). This dual base editor is referred to as a ‘saturated targeted endogenous mutagenesis editor' (STEME), which uses APOBEC3A as cytidine deaminase and adenine deaminase in fusion with D10A-mutated nCas9 and UGI for deamination of cytidines to uridines and adenosines to inosines, respectively. In situ directed evolution of endogenous plant genes is made easier with these dual base editors. STEME could also be used in plants to change cis elements in regulatory regions and perform high-throughput genome-wide screening (Zhu et al. 2020).

CBE-based editing

Another editor has been developed to induce particular deletions within the protospacer using cytidine deaminase Cas9, UDG, and AP lyase and is known as ‘APOBEC–Cas9 fusion-induced deletion systems' (AFIDs). Overexpression of UDG triggers base excision repair which results in uridine excision and formation of AP sites which can be nicked by AP lyases. This newly formed nick combines with a nearby DSB formed by Cas9 and leads to precise deletion mutation between the deaminated cytidine and the Cas9 cleavage site. hAPOBEC3A and the C-terminal catalytic domain of hAPOBEC3B (hAPOBEC3Bctd) are two cytidine deaminases that have been employed in AFIDs. Deletion mutation in between targeted cytidine and Cas9-induced DSB is made by hAPOBEC3A and hAPOBEC3Bctd produces deletion in between TC-preference motif and Cas9 induced DSB, resulting in more homogeneous products (Zhu et al. 2020). Nickase Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusion protein was used to drive cytosine to thymine conversion in prokaryotic cells, resulting in significant mutagenesis frequencies in E. coli and Brucella melitensis. CRISPR/Cas9-guided base-editing appears to be a viable alternative method for creating mutant bacterial strains (Zheng et al. 2018).

Prime editing

Despite the fact that CBE and ABE can produce exact base transitions, there are very few instruments for creating base transversions. A ground-breaking genome editing technology was developed to address this issue (Xu et al. 2020). Prime editor combines nCas9 (H840A) and reverse transcriptase in a complex with a pegRNA (prime editing guide RNA). But this assembly is not enough, thereby, including reverse transcriptase template and primer binding site at 3´ RNA of the pegRNA. The genetic information for the desired mutations is contained in the reverse transcriptase template, and hence this template is primed to insert the desired genetic information from template to the plant genome. The selected edit is then created via ligation, repair, and equilibration amongst the altered 3′ tail and the unedited 5′ tail. Following that, prime editor systems were constructed and tested in rice and wheat, and it was discovered that they could generate all 12 base substitutions, multiple base substitutions at the same time, as well as insertions and deletions. Furthermore, neither mammalian cells nor plants have proved the potential of primary editor to make bigger genomic alterations (hundreds of bases) or its specificity (Lin et al. 2020).

Limitations

Approximately 50% occurrence of off-target effects (OTEs) is a serious worry for using CRISPR/Cas9 for gene therapy. Bio-engineered Cas9 variants with lower OTE and improved guide designs are two current approaches to solving this issue. These OTEs can be reduced by coupling Cas9 nickase (nCas9) together with a sgRNA pair targeting the targeted regions of the DNA to cause the DSB. Cas9 variations that are deliberately tailored to prevent OTEs while keeping editing efficacy had also been done. A new guide design tool, sgDesigner, was recently developed to solve these restrictions using an in-silico plasmid library that comprised both the sgRNA and the target site in the same construct. This permitted for the collection of Cas9 editing efficiency data as well as the creation of a fresh training dataset free of the biases induced by existing models.

It is still difficult to get CRISPR/Cas material into large numbers of mature cells, which is a challenge in many therapeutic applications. Protoplast transfection, Agrobacterium-mediated transfer DNA (T-DNA) transformation, or particle bombardment are the most common approaches for delivering CRISPR-mediated editing reagents, such as DNA, RNA, and RNPs for the creation of altered plant trait (Omodamilola and Ibrahim 2018).

Application of CRISPR–Cas in PM interactions

CRISPR–Cas has a plethora of applications in understanding various facets of PM interactions from different perspectives. Furthermore, CRISPER–Cas can be employed to improve PM interactions for applications in agriculture and other fields.

Understanding PM interactions via CRISPR

Ethylene, jasmonate, and salicylic acid are plant hormones that regulate signaling pathways to enhance PM interactions (Pieterse et al. 2014). Understanding the pathogenic PM interactions, Red Queen dynamics (coevolutionary cycles sustained by pathogen-plant conflicts) would help us better understand their important evolutionary principles (Han 2019). Standard technologies like 16S ribosomal RNA-sequencing enable identifying the composition of a microbial community easier. Moreover, a variety of omics methods (gene, transcript, proteomic, and metabolomic) have enlightened the roles of plant-associated genes and pathways at the community level. These techniques are unable to distinguish between detrimental, neutral, and helpful interactions with the host plant. Given the necessity of microorganisms in plant fitness, finding key genes in PM interactions that regulate agronomic aspects would aid in the upgrading of desired plant traits for sustainable future agriculture and industry. Some major important uses of CRISPR-based GE tools is to research gene functioning in plants and microorganisms through genetic alteration. When contrast to partial gene silencing using the RNAi (RNA interference) technique, which leads to a partial phenotype, CRISPR-based technologies provide total knockdown of the target gene (Bisht et al. 2019). An important study over model microorganisms like rhizobia and the phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae have provided a mechanistic knowledge of genetic variables that cause mutual and harmful interactions with hosts. The CRISPR/Cas tool together with ssDNA recombineering, was recently created in the rhizospheric bacterium Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for gene deletion, insertion, replacement, and transcription suppression (Bisht et al. 2019). To investigate gene-level links in detrimental or pathogenic PM interactions, mechanistic studies on non-model microbial isolates are required. As a result, using robust CRISPR/Cas technologies to GE non-model microorganisms allows researchers to establish linkages between genes and functions (Shelake et al. 2019a).

Successful edits in plants against bacteria, fungi, oomycetes and viral resistance

Pathogenic PM and plant–insect interactions cause global yield deprivation ranging from 11 to 30%, with the widely held losses occurring in areas already experiencing food scarcity. Developing phytopathogen-resistant crop types has thus been a never-ending challenge for agronomic researchers. Natural mutations, cross-breading, hybridization, chemical/radiation and biological mutagenesis, have all been utilised to impart genetic alterations for enhanced disease-resistant plant cultivars. However, these approaches bring about a number of non-targeted changes, and screening being a time-consuming and labour-intensive task. CRISPR/Cas has evolved as a supplement (rather than a replacement) for traditional plant crossing and GM techniques. CRISPR gene editing technology has been employed for generation of plants resistant to bacterial, viral and fungal diseases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Employment of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology for generation of plants resistant to bacterial, viral and fungal diseases.

| Microbe | Host plant | Disease | GE tool used | Target gene | Gene targeted in plant/ pathogen | Notes | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||||||

| Pseudomonas syringae | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Bacterial speck | CRISPR/Cas9 | SlJAZ2 | Plant | Targeted gene interacts directly with coronatine, a bacterial product that aids in leaf colonisation | Ortigosa et al. (2019) | |

| Erwinia amylovora | Apple (Malus) | Fire blight | DIPM-1, 2 and 4 | DIPMs have a direct physical connection with Erwinia amylovora's disease-specific (dsp) gene, which may operate as a susceptibility factor | Malnoy et al. (2016) | |||

| Xanthomonas citri | Citrus | Citrus canker | CsLOB1 | CsLOB1 is a transcription factor that belongs to the Lateral Organ Boundaries (LOB) gene family. Candidate Targets of TAL Effectors PthA4 and PthAw are CsLOB1 | Jia et al. (2017) | |||

| Pseudomonas syringae, Xanthomonas spp., Phytophthora capsica | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Bacterial speck, Blight, and spot | SlDMR6-1 | DMR6 is knocked out, salicylic acid levels rise, triggering the synthesis of secondary metabolites and PR genes | Paula de Toledo Thomazella et al. (2016) | |||

| Xanthomonas oryzae | Rice (Oryza) | Bacterial blight | OsSWEET14 and OsSWEET11 | The pathogen binds to the promoter of the targeted gene and steals plant carbohydrates | Jiang et al. (2013) | |||

| Fungi | ||||||||

| Blumeria graminis | Wheat (Triticum) | Powdery mildew | CRISPR/Cas9 | TaEDR1 | Plant | Three Homologues of the targeted gene play a detrimental influence in plant immunity | Zhang et al. (2017) | |

| Phytophthora tropicalis | Cacao (Theobroma cacao) | Black pod disease | TcNPR3 | TcNPR3 regulates the cacao defensive response in a similar way to the Arabidopsis NPR3 gene | Fister et al. (2018) | |||

| Ustilago maydis | Maize (Zea mays) | Corn smut | bW2 and bE1 | Pathogen | The two homeodomains bW2 and bE1 proteins are encoded by b-locus and play a crucial role in pathogenic development as transcriptional regulators | Schuster et al. (2016) | ||

| Uncinula necator | Grape (Vitis) | Powdery mildew | MLO-7 | Plant | Sensitivity to a fungal pathogen | Malnoy et al. (2016) | ||

| Peronophythora litchi | Lychee (Litchi chinensis) | Downy blight | PAE4, and PAE5 | Pathogen | Pectin acetylesterases (PAEs) are critical in the pathogenicity of oomycetes | Kong et al. (2019) | ||

| Oidium neolycopersici | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Powdery mildew | SlMlo1 | Plant | Powdery mildew resistance provided by ol-2 (natural allele that confers broad-spectrum and recessively inherited resistance to powdery mildew) is caused by the loss of SlMlo1 function | Nekrasov et al. (2017) | ||

| Fusarium oxysporum | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), legumes, cotton | Wilt | FoSso1 and FoSso2 | Pathogen | Utilised for endogenous tagging of target genes and gene function research | Wang and Coleman (2019) | ||

| Phytophthora sojae | Soybean (Glycine max), Vegetables | Damping off, Powdery mildew, | Avr4/6; Oxysterol binding protein-related protein | Virulence proteins enter host cells and promote host susceptibility | Miao et al. (2018) | |||

| Magnaporthe oryzae | Rice (Oryza sativa) | Rice blast | OsERF922 | Plant | Negative regulator of blast fungus | Wang et al. (2016) | ||

| Participate in the exocyst complex and interact with defense proteins | ||||||||

| OsSEC3A | ||||||||

| Botrytis cinerea | Grape (Vitis) | Gray mold | WRKY52 | Transcription factor involved in response to biotic stress | Wang et al. (2017) | |||

| Leptosphaeria maculans | Canola (Brassica napus) | Blackleg disease | Histidine kinase | Pathogen | To study resistance mechanism against a pesticide (Iprodione) | Idnurm et al. (2017) | ||

| Ustilaginoidea virens | Rice (Oryza sativa) | False smut | USTA ustiloxin and UvSLT2 MAP kinase | UvSLT2 knockout increased susceptibility to cell wall stressors while increasing tolerance to hyperosmotic and oxidative stresses. The UvSlt2 MAP kinase pathway is important for cell wall integrity | Liang et al. (2018) | |||

| Alternaria alternata | Sunflower (Helianthus) | Black molds | pyrG, pksA, and brm2 phosphate decarboxylase, polyketide-synthase, and 1,3,8-THN reductase | – | Wenderoth et al. (2017) | |||

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum | Flowers, Vegetables | White mold | Ssoah1 | The Ssoah1 gene allowed to validate that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutants are loss-of-function and to investigate novel elements of the mutant phenotype | Li et al. (2018) | |||

| Virus | ||||||||

| CLCuKoV, TYLCSV, TYLCV, BCTV, MeMV, | Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | Viral (DNA) | CRISPR/Cas9 |

IR, coat protein and Rep Intergenic replication origin (IR), capsid protein (CP), and Rep protein's RCRII motif |

Pathogen | – | Ali et al. (2016) | |

| eBSV | Banana (Musa) | Three target sites in viral genome | – | Tripathi et al. (2019) | ||||

| WDV | Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | Rep, LIR, MP | – | Kis et al. (2019) | ||||

| BSCTV | Arabidopsis, Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | CP, IR and Rep | – | Ji et al. (2015) | ||||

| BeYDV | Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | Rep protein encoding gene, and long intergenic region (LIR) | – | Baltes et al. (2015) | ||||

| TMV | Arabidopsis, Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | Viral (RNA) | ORF1a, ORFCP, 3´- UTR | – | Zhang et al. (2018) | |||

| CVYV, ZYMV, PRSV-W, TuMV |

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus), Arabidopsis |

eIF4E/exon | Plant | Interacts directly with viral proteins and aids in viral replication | Chandrasekaran et al. (2016) | |||

| CBSV | Cassava (Manihot esculenta) | Brown streak (RNA) | nCBP-1 and nCBP-2/exon | Directly interact with viral protein and helps viral replication | Gomez et al. (2019) | |||

| TuMV | Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | Viral (RNA) | CRISPR/Cas13a | Coat protein genes, TuMV-GFP, Helper component proteinase silencing suppressor (HC-Pro), TuMV-GFP | – | Aman et al. (2018) | ||

CRISPR approach to amplify the production of Secondary Metabolites in plants and microbes

Plants and its accompanying microorganisms produce various secondary metabolites (SM), usually by chemical routes. Many of these SMs have been used as nutrition, medications, repellents, perfumes, tastes, and colouring compounds, despite their importance in plant or pathogenic defence processes. Several plant microbiome researches offer fascinating insights into the microbial taxa that enable plant SMs synthesis. Seed microbiomes of therapeutic plants like Salvia miltiorrhiza, in particular, reveal an overlap of fungal and bacterial taxa with maize, bean, rice, and rapeseed. Furthermore, PM-associated microorganisms as well as the host plant have mutual terpenoid metabolic biosynthesis route, indicating their capability as a storehouse for SM-related genes. Furthermore, geographic location is one of the main reasons for the production of particular SM, because of direct relation between plant metabolome and related microbiome. CRISPR-mediated editing of PM-associated genes implicated in the SM pathway offers a unique and appealing technique for increase in the biosynthesis of stable and bioactive SMs (Shelake et al. 2019a). Various secondary metabolites produced by plants and microbes in conjugation with each other were discovered as a result metabolic engineering investigation. SMs modified by CRISPR tools are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

CRISPR/Cas9 technology for modulation of secondary metabolites for the benefit of plants and microbes

| Secondary metabolite | Genes targeted | Tool used | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbe | ||||

| Beauveria bassiana | Uridine synthesis | Directed mutagenesis of ura3 gene | CRISPR Cas9 | Chen et al. (2017) |

| Trichoderma reesei | Uridine synthesis | Qm6a (Wild-type strain), Rut-C30 (mutant strain) under control of the Ppdc and Pch1 promoter, respectively | Liu et al. (2015) | |

| Escherichia coli | Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA | Repression of ppsA, eno, glyA, adhE, mdh, fumC, sdhABCD, sucC and cite; ppsA, eno, adhE, mdh, fumC, sdhA, sucC and cite, respectively | CRISPRi | Wu et al. (2015) |

| Myceliophthora | Cellulase production | Gene disruption of cre-1, res-1, gh1-1, and alp-1 | CRISPR Cas9 | Liu et al. (2017) |

| Aspergillus niger | Galactaric acid production, pigment production | Knock out of gene with ID 39,114 | Kuivanen et al. (2016) | |

| Shiraia bambusicola | Hypocrellin production | SbaPKS gene knock-out (engaged in hypocrellin production, and hypocrellin plays an important role in S. bambusicola's pathogenicity on bamboo leaves) | Deng et al. (2017) | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Trypacidin biosynthesis | Knock out of tynC gene | Weber et al. (2016) | |

| Plant | ||||

| Opium poppy | Morphine biosynthesis | Knock out of 4′OMT2 gene | CRISPR Cas9 | Alagoz et al. (2016) |

| Tomato | γ-Aminobutyric acid, GABA | Knock out of two target sites in slyPDS gene | Li et al. (2018) | |

| S. miltiorrhiza | tanshinone Biosynthesis | Knock out of SmCPS1 gene | Li et al. (2017) | |

| Dendrobium sp. | Lignocellulose biosynthesis | Increased expression of GUS, HygR gene | Kui et al. (2017) | |

| Camelina sativa | triacylglycerol synthesis | Altering by multiple mutations in CsDGAT1 gene or each CsDPAT1 homeolog | Aznar-Moreno and Durrett (2017) | |

| Tobacco | Glycan biosynthesis | Knock out of XylT and FucT gene | Mercx et al. (2017) | |

| S. miltiorrhiza | Phenolic acid | Knock out of SmRAS gene | Zhou et al. (2018) | |

Conclusion

One of the emerging strategies to fulfil future food demand is to exploit PM interactions for their optimal use in sustainable agriculture. In the past, only a few representative species were used in research on PGP microorganisms and microbe-mediated plant protection. To widen the range of PM engineering for agriculture, extensive molecular investigations on microbe-mediated plant advantages have been done in recent years. Better understanding of PM interactions and their use for future agriculture can be made possible through new emerging gene editing tool CRISPR which beholds a lot of potential in this area. To comprehend the basics and advances of community level biological mechanisms, immense number of plant species should be studied and extensive sequencing investigations of meta-transcriptomic data and plant microbiome should be done. CRISPR-based applications in sustainable agriculture will be aided by the identification of particular plant or microbial candidate genes influencing agronomic parameters. Which plant genes allow crops to influence the rhizosphere microbiota? Which plant genes allow crops to shape the rhizosphere microbiota? What impact do microorganisms have on the host plant? Plants and microorganisms communicate in a variety of ways. These inquiries will manifest a direct relationship between plants and microbes which can be utilized improving plant traits and crop productivity.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Joung J, Slaymaker IM, Cox DBT, Shmakov S, Makarova KS, Semenova E, Minakhin L, Severinov K, Regev A, Lander ES, Koonin EV, Zhang F. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science. 2016;353:aaf5573. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abudayyeh O, Gootenberg J, Essletzbichler P, et al. RNA targeting with CRISPR Cas13. Nature. 2017;550:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nature24049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adli M. The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04252-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agler MT, Ruhe J, Kroll S, Morhenn C, Kim S-T, Weigel D, et al. Microbial hub taxa link host and abiotic factors to plant microbiome variation. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagoz Y, Gurkok T, Zhang B, Unver T. Manipulating the biosynthesis of bioactive compound alkaloids for next-generation metabolic engineering in Opiumpoppy Using CRISPR-Cas 9 genome editing technology. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep30910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z, Ali S, Tashkandi M, Zaidi SSEA, Mahfouz MM. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated immunity to gemini viruses: differential interference and evasion. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26912. doi: 10.1038/srep26912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman R, Ali Z, Butt H, Mahas A, Aljedaani F, Khan MZ, Ding S, Mahfouz M. RNA virus interference via CRISPR/Cas13a system in plants. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznar-Moreno JA, Durrett TP. Simultaneous targeting of multiple gene homeologs to alter seed oil production in Camelinasativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58:1260–1267. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes NJ, Hummel AW, Konecna E, Cegan R, Bruns AN, Bisaro DM, Voytas DF. Conferring resistance to gemini-viruses with the CRISPR-Cas prokaryotic immune system. Nat Plants. 2015;1:4–7. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]