Abstract

Background.

Efforts to confront the type 2 diabetes (T2D) epidemic have been stymied by an absence of effective communication on policy fronts. Whether art can be harnessed to reframe the T2D discourse from an individual, biomedical problem to a multilevel, communal and social problem is not known.

Method:

We explored whether spoken word workshops enable young artists of color to convey a critical consciousness about T2D. The Bigger Picture fosters creation and dissemination of art to shift from the narrow biomedical model toward a comprehensive socioecological model (SEM). Workshops offer (1) public health content, (2) writing exercises, and (3) feedback on drafts. Based on Freire and Boal’s participatory pedagogy, workshops encourage youth to tap into their lived experiences when creating poetry. We analyzed changes in public health literary and activation among participants and mapped poems onto the SEM to assess whether their poetry conveyed the multilevel perspective critical to public health literacy.

Results.

Participants reported significant increases in personal relevance of T2D prevention, T2D discussions with peers, concern about corporations’ targeted marketing, and interest in community organizing to confront the epidemic. Across stanzas, nearly all poems (95%) featured >three of five SEM levels (systemic forces, sectors of influence, societal norms, behavioral settings, individual factors); three-quarters (78%) featured >four levels.

Conclusions.

Engaging youth poets of color to develop artistic content to combat T2D can increase their public health literary and social activation and foster compelling art that communicates how complex, multilevel forces interact to generate disease and disease disparities.

Keywords: health disparities, preventive medicine, diabetes, social determinants of health, health communication, health literacy, communication theory

BACKGROUND

In the United States, type 2 diabetes (T2D) is rapidly rising among youth (Demmer et al., 2013; May et al., 2012). Public discourse around the root causes of this crisis has largely focused on genetics and individual behaviors, using the biomedical model (Gloyn & McCarthy, 2001; Norris et al., 2002). Despite an increasing body of research conceptualizing T2D as a multilevel problem best understood through a socioecological model (SEM; Atkiss et al., 2011; Basu & Narayanaswamy, 2019; Hill et al., 2013), few health communications have adopted this framework (Williams & Buttfield, 2016). A majority of communication interventions to combat T2D target individual-level behaviors, rather than the additional structural factors associated with poverty, discrimination, oppression, exclusion, family disruption and the cultural, social, educational, political, and economic systems that perpetuate and, at times, institutionalize differential exposure risk (Hill-Briggs et al., 2020). In the case of T2D, exposures reinforced by structural inequalities include poor access to high-quality food, high consumption of accessible “junk food” (Berkowitz et al., 2018), limited safe sites for recreation and physical activity (Den Braver et al., 2018), high rates of sedentarism (Patterson et al., 2018), and levels of acute and chronic stress that induce hormonal changes that promote metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance (Yan et al., 2016). This discrepancy reflects the fact that the SEM is (a) a less funded, recognized, and disseminated scientific framework than those focused on genetic, metabolic, and individual processes (Mabry et al., 2008); (b) considered “too complex” for the average news consumer (Amed, 2015; Zimmet, 1999) due to communally low levels of public health literacy (Rudd, 2007); and (c) contradictory to a dominant U.S. cultural ideology of “rugged individualism” that contends that wealth and health result from individual efforts (Hirschman, 2003).

Development of public health literacy in youth, particularly youth of color, may serve as a protective factor to combat the spread of T2D in communities at risk. Public health literacy is the degree to which individuals and groups can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act on information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community (Freedman et al., 2009). The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Health Communications Research Program at the Center for Vulnerable Populations (cvp.ucsf.edu) and Youth Speaks (youthspeaks.org) collaborated to develop a youth-centered and youth-generated campaign to increase diabetes-related public health literacy. Our pedagogical approach represents a hybrid application of the educational concepts of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, with aesthetic principles of delivery and production adopted from Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed. These approaches highlight engagement of lower literacy learners as experts and low-income individuals as performers who question the social order imposed by the dominant culture (i.e., capitalism, racism) and foment activism through artistic application (Boal, 2000; Freire, 1972; Schillinger et al., 2017). We delivered workshops that used participatory, multidisciplinary methods to encourage youth participants to reflect on both health and social content by tapping into their lived experiences growing up in low-income communities and communities of color. Workshops supported participants to operationalize, integrate, and translate their interpretations to develop spoken-word poems by building on Youth Speaks’ central tenet of writing: harnessing “life as primary text.”

PURPOSE OR AIMS

The building of a critical consciousness among youth can enable a paradigm shift whereby root causes of social disparities can be challenged and reframed into community strength and advocacy (Breinbauer & Maddaleno, 2005; Schillinger & Huey, 2018). Promotion of resiliency and empowerment of youth through artistic engagement can improve the health and quality of life for youth and populations at large (Berberian & Davis, 2019; Clonan-Roy et al., 2016; Lardier et al., 2018). The Bigger Picture (TBP) diabetes prevention campaign (www.thebiggerpictureproject.org) is a collaboration between the UCSF Health Communications Research Program at the Center for Vulnerable Populations (cvp.ucsf.edu) and Youth Speaks (youthspeaks.org). In TBP, we aimed to use spoken-word as the transformative currency for youth poets to “change the conversation” about T2D from the predominant individual “shame and blame” narrative toward “changing the game by taking aim” at the complex, interacting sociopolitical factors that generate disease and health inequities (Hill-Briggs et al., 2020; Morgan, 2018; Rogers et al., 2017; Schillinger & Huey, 2018; Schillinger et al., 2018).

The creation of spoken-word art—inspired by an interactive public health and artistic curriculum—was intended to position youth artists as messengers of truth and agents of change, educating and inspiring themselves and their communities in the process. Youth spoken-word has been shown to be an effective means of enhancing “literate identities” for youth by increasing their confidence within a supportive community aimed to disrupt the status quo while instilling sense of purpose and leadership as modern “cultural theorists” (Ibrahim, 2020; Weinstein, 2018). Youth spoken-word has been described as being based in a transformative “critical hip-hop pedagogy” that fosters “agency by enabling artists to reclaim their bodies from oppressive and repressive academic praxes that downcast the role of cultural identity and construction,” allowing “reflection and amplification of the voice of youth disempowered by traditional educational pedagogy” (Akom, 2009; Biggs-El, 2012).

While some of the audience-level impacts of the TBP campaign have previously been described (Rogers et al., 2017; Schillinger & Huey, 2018; Schillinger & Jacobson, 2016; Schillinger et al., 2017; Schillinger et al., 2018), the efficacy of TBP curriculum to increase the public health literacy of the young poets who created the campaign’s content has not been evaluated. Specifically, the extent to which the SEM was integrated into their mental models and artistic messages has not been assessed. The objective of this article is to (1) briefly describe the pedagogical framework behind the TBP youth development process, (2) evaluate the effectiveness of the workshops to increase public health literacy among youth poets of color, and (3) explore whether their resultant spoken-word art represents and communicates the SEM as it relates to T2D.

METHOD

Curricular Content

Workshops aimed to enable poet participants to create content that communicates the campaign’s overarching objective to “change the conversation” about T2D away from an individual narrative and toward the SEM—a narrative that places the individual as subject to a number of dynamic social-environmental forces that shape behaviors and determine health trajectories (Rogers et al., 2017; Schillinger et al., 2017). Workshops sought to transform youth participants from powerless targets of metabolic dysfunction to powerful messengers of resistance and change for health promotion. These objectives—changing the public narrative, promoting health as a shared value, and motivating civic engagement—align with The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health Action Framework (Chandra et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2019).

Between 2013 and 2017, we offered seven workshops (10 hours total: 2 hours daily for 5 days with five to seven attendees) in various locations in California’s Bay Area. The curriculum of TBP aimed to transmit a level of social consciousness about, and inspire activism around, the T2D epidemic. Specifically, the workshops sought to affect youth artists’: (1) appreciation that T2D affects youth, (2) comprehension of the epidemic’s root causes and their disproportionate impact on communities of color, (3) perception of T2D as salient to their lives, (4) social norms related to dietary preferences and blind consumerism, (5) activation to engage in systemic solutions, and (6) creation of poems that align with TBP’s socioecological ethos. An expert in diabetes-related public health communication (DS) and a poet-mentor collaboratively selected workshop themes. In the first two sessions, the public health expert led interactive discussions based on clinical narratives, T2D epidemiology (including rising incidence in youth and socio-environmental drivers of health disparities) and corporate targeted marketing strategies. T2D was described as resulting from multiple levels of influence (individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, political, and historical). In the remaining sessions, the poet-mentor prompted youth to write through the prism of their own lived experience (“life as primary text”) so that their artistic products would resonate as authentic and consistent with their values (Schillinger et al., 2017). Poets refined their pieces over the course of the workshops based on peer and poet-mentor feedback. While the provision of feedback was frequent, the ideas, themes, and linguistic content of all pieces were conceived and authored by individual youth themselves.

Workshops neither encouraged nor discouraged specific types of individual behavior change (e.g., “eating right and exercising”). Rather, they steered conversation away from individually based discourse toward the curriculum’s overarching objective of increasing “public health literacy” by elucidating how exposures and risk factors play out at family, neighborhood, community, organizational, market and socio-political levels. An example of TBP workshops’ process can be viewed here: https://youtu.be/QKkpByVJ7pQ.

Research Design

We utilized a case study mixed methods design (Fetters et al., 2013; Guetterman & Fetters, 2018; Wisdom et al., 2012) to evaluate the effects of TBP workshop curriculum on youth participants’ engagement, activation, and integration of pedagogical content into their artistic products. We employed TBP pedagogy as our case study, using both quantitative and qualitative data to both explore and report on the nuanced complexities of how T2D is (or is not) experienced and understood as a socioecological disease for youth of color. We administered surveys with closed and open-ended questions to youth participants before and after the workshops to assess effectiveness. We used thematic analysis to code the open-ended questions of the survey. We subjected all submitted poems to content analysis to determine the extent to which youth poets’ artistic products reflect and convey the multilevel SEM of T2D and quantified these analyses to be able to communicate the relative prevalence of each level.

Population and Recruitment

At the time of these workshops, Youth Speaks Inc was reaching over 40,000 high school students in the Bay Area through its school-based programming, which focuses on schools serving low-income communities. Of these, a subset of motivated students enrolled in Youth Speaks’ extracurricular programming. From this smaller pool, Youth Speaks invited poets to engage in TBP workshops with a stipend that ranged from $50 to $100. Over the course of 4 years, 37 youth participated. The Youth Speaks facilitator administered pre- and postworkshop questionnaires developed by the UCSF research team; completion was entirely voluntary and not tied to the stipend. The UCSF Institutional Review Board approved the study. All subjects also signed consent to allow publication and dissemination of their work via social media.

Quantitative Data

Participants filled out a preworkshop questionnaire at the beginning of the first workshop and a postworkshop questionnaire after the final session. Questionnaires—which we specifically developed for this project—measured demographic data and perceptions of T2D’s relevance to their lives, beliefs regarding corporate targeting to communities of color, dietary behavioral norms, social activation, and public health literacy using Likert-type response options. To compare pre- and postworkshop responses, we calculated mean rank using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Completion of the questionnaires was voluntary and not a focus of the workshops.

Qualitative Data

Questionnaire-Based Data.

The questionnaires also contained four open-ended postworkshop questions: (1) How can TBP reach youth? (2) What have been the biggest lessons of the workshop? (3) How can you be agents of change? and (4) How can the workshop be improved? We applied thematic analysis based in grounded theory to analyze responses to the questions.

Poetry-Based Data.

The poems tangibly reflect how well participants were able to integrate individual, familial, social, political, systemic, and environmental understandings of the pathogenesis and spread of T2D into their artistic voices. As a result, we analyzed the artistic products to determine the extent of which participants’ content recast the T2D epidemic as a socially and environmentally driven malady requiring communal action. While a subset of poems was turned into video poems disseminated online (www.thebiggerpictureproject.org), we include all submitted poems in our current analyses (N = 37).

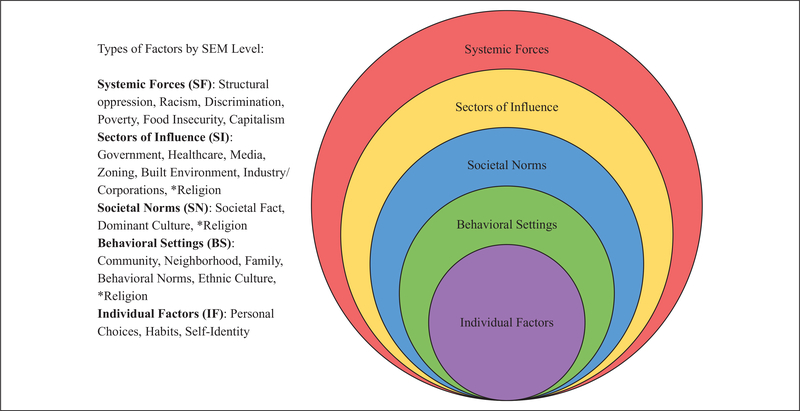

We employed a modified SEM to categorize which levels of influence poets focused on in their work (Figure 1). Adapted from an established SEM of T2D (Hill et al., 2013), the model contains five concentric levels of influence, from outer to inner ring: systemic forces, sectors of influence, societal norms/ills, behavioral settings, and individual factors. We defined systemic forces as larger historic and/or contemporary forces that reinforce health and social disparities (e.g., structural oppression and trauma, racism, discrimination, poverty, food insecurity). We defined sectors of influence as institutional entities, such as government, health care, media, and industry that drive consumerism, affect markets, regulate food systems, determine geographic zoning, and shape the built environment; societal norms as facts and behaviors accepted as mainstream in American culture; behavioral settings as practices deemed normative by a subgroup of people in associated settings (defined by community, family, work, religious group); and individual factors as personal habits, choices, or perspectives.

FIGURE 1. Modified Socioecological Model (SEM) of Type 2 Diabetes.

*Religion: Factor that is multidimensional in impact, transcending Sectors of Influence, Societal Norms, and Behavioral Settings.

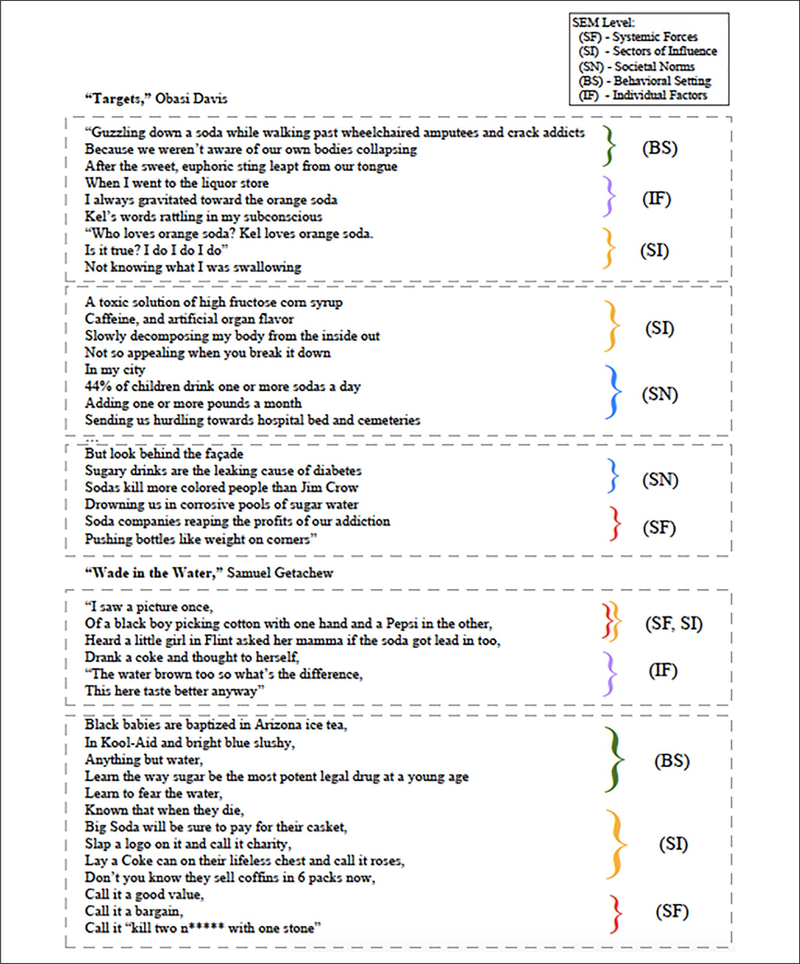

To map each poem against this SEM, we selected the stanza as the unit of analysis within each poem. In those poems without clear stanza designations, the primary reviewer (EA) subdivided poems using natural breaks (~6–10 lines), which were then treated as stanzas in subsequent analyses. We measured the proportion of poems that contained: all five domains; four of five domains; three of five domains; and so on. We considered the TBP workshop to be effective a priori if a majority of poems contained ˲three socioecological domains. To determine the SEM gestalt of each stanza, we assigned each line a primary and (when appropriate) a secondary socioecological domain code (see Figure 2). By adding up the number of domain codes across stanzas, we also assigned each poem a primary and secondary socioecological domain.

FIGURE 2. Application of Socioecological Model (SEM) to Poetic Stanzas.

Figure 2 was provided as a low-res image file and will likely print blurry. To help render a higher quality figure for print, please supply the figure in its native file format (i.e., the original file generated by the application used to create it; e.g., if the figure was created in PowerPoint, submit the PowerPoint file). If you used proprietary software to create the figure, please export the figure in one of the following formats: .PDF, .EPS, .SVG, or .AI.

To ensure coding reliability, the team met on four occasions to discuss and compare coding results on subsets of poems. Through this iterative process, we generated consensus on how to code poems using the aforementioned framework. We created a coding manual with domain definitions that communicated rules and employed exemplary excerpts that demonstrated associated results. Next, we randomly selected five poems to be separately analyzed by three different coders. This process initially revealed inconsistencies due to varied interpretations of how domains were defined. After refining our coding manual accordingly, the three coders analyzed an additional five poems. This final version yielded a high interrater reliability, with a Cohen’s Kappa score of 0.8 for the identification of the primary domain of each poem.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Twenty-four of 37 participants (64.9%) completed both the pre- and postworkshop questionnaires; not every item was responded to. Respondents were aged 16 to 24 years, 54.6% self-identified as female, 52.3% as African American, 33.3% Latinx, 4.8% Asian/Pacific Islander, 4.8% Multiethnic, and 4.8% White/non-Hispanic. Ten percent completed college, 25.0% some college, 35.0% graduated high school, and 30.0% had not graduated high school. A majority of participants (82.6%) reported knowing someone with diabetes, 47.4% identified a close relative with diabetes and three participants (12.5%) had been told by a health professional that they have either prediabetes or T2D.

Quantitative Analysis

Comparing pre- and postworkshop questionnaires, participants reported significantly greater relevance of T2D to their lives (p = .001) as well as significant increases in frequency of discussing T2D with peers (p = .03); concern that corporations target youth of color (p = .04); and interest in working with community organizations to confront the T2D epidemic (p = .04). While workshop participants reported increases in personal interest in T2D prevention, heightened awareness of soda’s contribution to T2D, and greater intent to avoid soda, these changes were not statistically significant.

Qualitative Analysis

Questionnaire-Based Data.

Analysis of open-ended questions revealed that participants felt TBP could reach youth by providing relatable content and spreading information by direct outreach. They shared that youth could be reached by “… more workshops like these, using the arts to inform and have youth critically evaluate how T2D affects them.” They overwhelmingly cited the role of structural forces, like institutional racism, as one of the biggest lessons. One participant stated that “Fighting against T2D is a combination of calling out the disproportionate spreading of the disease and self-accountability.” Another stated that they learned that T2D “ is a social justice issue versus a disease that people randomly get.” They felt that inspiring others through their art was a way to become agents of change for their communities. After the workshop, one participant noted that “We hold the key to create a culture that promotes healthy living,” and “Youth can be important agents of social change for any social problem, and we can do it by organizing.” To improve the workshop efficacy, one poet recommended “more structure in the writing exercises to produce more poems that are on topic—better use of time, less videos, less unstructured conversation and more writing and editing.”

Poetry-Based Data.

To convey how the poems integrated content consistent with the multilevel SEM and to provide transparency as to how we coded poems, we provide excerpts from two poems (see Figure 2). We have labeled lines in each stanza to designate associated SEM levels. Warning: Some of the content contains offensive language.

We analyzed 37 poems containing a total of 456 stanzas. A majority of the poems (64.8%, 24) had stanzas that featured all five domains, 78.4% (29) featured at least four domains, and 94.6% (35) featured at least three domains. No poem featured only one domain. Table 1 provides excerpts demonstrative of each domain. With respect to the five levels in the SEM, sectors of influence was the most prevalent primary domain across the 37 poems (37.8% of poems), followed by individual factors (24.3%). Sectors of influence and systemic forces had equal prevalence as secondary domains (29.7%).

TABLE 1.

Qualitative Analysis of Poems: Primary and Secondary Domains of Applied SocioEcological Model

| Domain | Primary, N (%) | Secondary, N (%) | Excerpt(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Systemic Forces | 4 (10.8) | 11 (29.7) | “In the Central Valley where immigrants grow food for the entire country. Yet struggle to find food to at. Struggle to find clean water to drink.” “The rich eat the apples and feed the cores to the poor. We’re at the bottom of the food chain.” |

| Sectors of Influence | 14 (37.8) | 11 (29.7) | “I fell under the influence of the machine. Forcefed color-loaded, sugar-coated lies by way of television tubes. Targeting me, my sister, my brothers since Saturday morning cartoons.” |

| Societal Norms | 3 (8.1) | 3 (8.1) | “Black children are 5.5 times more likely to drown than white children … more than 1 in 2 black children are inadequately hydrated.” |

| Behavioral Setting | 7 (18.9) | 9 (24.3) | “de cariño my familia would buy me my favorite snacks … never did I imagine these sweet gesture of love were actually poison … in colorful wrappers and sold as cultura.” “no one really tells you that being Gordito is cute when you are a baby …” |

| Individual | 9 (24.3) | 3 (8.1) | “This is my body. This is my blood. I don’t wanna be skinny, just wanna incorporate movement without running out of breath, but it’s like I fiend for high fructose corn syrup no matter how sick I feel after.” |

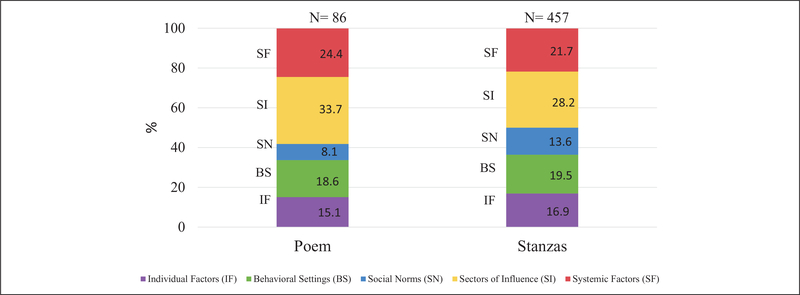

Figure 3 illustrates that the cumulative frequency of the combination of primary and secondary domains across poems, including sectors of influence (33.7%), systemic forces (24.4%), and behavioral setting (18.6%). Figure 3 also illustrates the cumulative frequency with which each SEM level was coded within each stanza across poems. Of the 456 stanzas, 28.2% featured sectors of influence as a primary or secondary domain, while 21.6% featured systemic forces and 19.4% featured behavioral settings.

FIGURE 3. Prevalence (%) of Primary and Secondary Socioecological Domains at the Poem Level (N = 86) and at the Stanza Level (N = 457).

Note. All domains tied for secondary level were included. There were no ties for primary level.

DISCUSSION

T2D is exceedingly prevalent among U.S. adults and is now affecting youth of color. The nation’s ability to confront this growing epidemic as a multilevel social problem has been stymied by an absence of effective communication by both medical and public policy communities. TBP workshops delivered: (1) public health content in both narrative and factual forms, (2) writing prompts to stimulate creativity, and (3) iterative performance and feedback sessions to encourage artistic elaboration. We explored whether these interactive educational and artistic experiences can empower youth poets of color to harness their voices to change the conversation of T2D away from a narrow individual behavioral problem (represented by the biomedical model) toward a more multilevel, action-oriented, societal problem (represented by the SEM). Specifically, we utilized a mixed methods approach to determine whether spoken-word positions young artists of color to integrate and convey a critical consciousness about T2D as a function of participating in workshops cofacilitated by public health and arts mentors.

We found that, after the workshops, participants reported greater levels of public health literacy and activation related to T2D. We further found evidence that the curricular content and workshop process were effective, as 95% of submitted poems featured at least three of five SEM levels, and nearly two thirds featured all five. At both the poem and stanza levels, the most frequent domains were sectors of influence, systemic forces and behavioral settings, suggesting that youths’ mental models for T2D extended beyond individual behavioral factors. As such, youth poets met TBP campaign’s objective to identify and integrate the multifaceted SEM of T2D into their poetry. Their poems shifted discourse away from individual-level “shame and blame” about unhealthy behavioral practices toward larger communal domains such as the systemic forces and the sectors of influence that determine health-jeopardizing exposures, risks, and behavior. While nearly one quarter of poems did feature individual factors as a primary domain, poets more frequently and collectively called out factors beyond the individual—such as poverty, racism, food insecurity, consumerism, and institutional oppression—as contributing to the epidemic and its disproportionate impact on low-income communities and communities of color.

We conclude that engaging youth of color to develop artistic content to combat T2D via a collaborative and participatory approach led by public health practitioners and artists was an effective method for social activation among this cohort of youth. Enabling youth of color to use their “life as primary text” may have the ability to promote civic engagement while increasing public health literary though communications that reduce communal risk for the development of diseases such as T2D. This process can support youth to produce art that conveys the complex, multilevel mechanisms of disease and health disparities—in novel, compelling, and understandable ways (Schillinger et al., 2018)—so as to influence public policy and instigate social change (Schillinger & Huey, 2018). To date, many of the poetic products of TBP have been produced into public service announcements disseminated to local at-risk high schools in the form of an interactive school assembly, online via social media, and in collaboration with local health departments to reduce sugary drink consumption (Rogers et al., 2014; Schillinger & Jacobson, 2016).

Poetry and other forms of expressive writing have previously been identified as a therapeutic tool to both foster self-control and voice prior trauma while accessing one’s “unconscious self” (Stuckey & Nobel, 2010), and have been described as effective in dismantling oppression for social change via “group-centered leadership” and collective transformation (Chepp, 2016). While there remains a paucity of quantitative data to support the impact of poetry on social change, extensive narrative history dating back to the origin of the Greek word “poiesis” links poetry to the formation of ideas that communicates a “societal creativity” able to transcend from individuals toward society at large (Manresa & Glăveanu, 2017). Inherent in its origins, social change requires improvisation and collaboration built on old traditions; as such poetry informs praxis as the underlying dialogue between the arts and human activity. Youth—skilled in both improvisation and collaboration—can be powerful catalysts for public policy change, exemplified by the efforts of Floridian youth leaders and their #NeverAgain social-media campaign against gun violence (Alter, 2018; Fat Company, 2018).

Poetry provides an ideal canvas for the exploration of identity and environment, inviting opportunity to question historical knowledge within predefined socioecological determinants. There also is a body of evidence to support harnessing spoken-word poetry and hip-hop culture both in youth-based programming as well as in cognitive behavioral therapy as to contribute to a better psychological well-being (Alvarez & Mearns, 2014; Croom, 2015; Tyson, 2002). Spoken-word writing in youth-focused programming has demonstrated validity in empowering critical thinking that allows some youth to achieve positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment (PERMA); the core building blocks of well-being and self-expression that may propel behavioral change and community connectedness (Croom, 2015; Tyson, 2006).

The ability of the youth participating in TBP workshops to create art that communicates a complex, multilevel socioecological framework and promotes a progressive, evidence-based understanding of a disease likely reflects not only TBP’s participatory pedagogical process but also the unique attributes of the participants. While all participants, as prior beneficiaries of Youth Speaks’ programming, had been artistically primed to create compelling poetry, these youth showed an ability to translate complex social and scientific/clinical content into authentic and credible messages by applying their lived experiences to their work. The existence of robust, youth-oriented spoken-word communities across the country, including ~70 sister organizations in The Brave New Voices Network enhances the feasibility of scaling up the TBP workshop process (Schillinger & Huey, 2018).

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the small sample of participants who completed both pre- and postworkshop questionnaires limited statistical power. Nonresponders may have responded differently, which undermines internal validity. However, the poetry’s overall alignment with the SEM across all participants suggests that even nonresponders likely experienced increases in public health literacy. Second, the absence of a control group limits causal conclusions; the high proportion of poems demonstrating the complex interplay of socioecological forces may in part be a function of poets’ prior exposure to Youth Speaks’ general programming, not just TBP workshops. Third, our case study with mixed methods design, while innovative and informative, may suffer from other threats to internal validity, a problem related to any attempt to objectify poetic inquiry (Prendergast, 2009). Analyzing written words, particularly those extracted from performative art, is potentially fraught, limited by the dependability and confirmability due to coders’ unique relationships with words or phrases, and their varied lived experiences. We attempted to enhance confirmability by diverse representation and overlap of gender, race/ethnicity, and poetic experience of our coders (two were female and one male; one was Black/non-Hispanic, one White/Hispanic and one White/non-Hispanic; only one coder had been exposed to the poems prior to this study).

Implications for Practice and Policy

The results of our study build on prior research that describes the transformative impact that expressing their perspectives on health and disparities through art (Kilaru et al., 2014) can have for marginalized communities and adds to the literature on how youth can become powerful instigators of public health movements and agents of social change (Yaffe, 2018). Scaling up TBP workshops in other regions could empower youth artists of color to apply their voices to create novel public health messages that influence policy by promoting systemic change for equity and combating misinformation (Breland et al., 2017). Indeed, the disproportionate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the nation-wide protests related to police brutality and racism have created an unprecedented opportunity to emphasize how so-called “structural factors” drive health and well-being.

We found that participatory workshops cofacilitated by experts in public health and the arts can be an effective means to increase public health literacy and foster social activation among low-income and ethnically diverse youth artists of color. Such a process can catalyze the creation of art that conveys critical content to a range of audiences, helping shift attention to more upstream and remediable factors (Chittamura et al., 2020; Schillinger & Huey, 2018; Schillinger et al., 2018). To date, TBP’s artistic products and related performances of this work have contributed to local policy changes related to sugary beverages, such as taxation and mandating warnings on advertisements, and installations of freshwater stations in low-income neighborhoods (Schillinger & Huey, 2018; Schillinger & Jacobson, 2016). As such, TBP represents a case study demonstrating that collaboration between public health and the arts can foster compelling communications capable of engaging community by enhancing public health literacy and advancing public policy to promote health and reduce disparities.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ Note: This work was supported by an Evidence for Action grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; a Leadership Award from The James Irvine Foundation; and NIH/NIDDK P30 DK092924 Center for Diabetes Translational Research.

REFERENCES

- Akom AA (2009). Critical hip hop pedagogy as a form of liberatory praxis. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42(1), 52–66. 10.1080/10665680802612519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alter C (2018, March 22). The school shooting generation has had enough. Time. https://time.com/longform/never-again-movement/ [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez N, & Mearns J (2014). The benefits of writing and performing in the spoken word poetry community. Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(3), 263–268. 10.1016/j.aip.2014.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amed S (2015). The future of treating youth-onset Type 2 diabetes: Focusing upstream and extending our influence into community environments. Current Diabetes Reports, 15(3), 7. 10.1007/s11892-015-0576-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkiss K, Moyer M, Desai M, & Roland M (2011). Positive youth development: An integration of the developmental assets theory and the socio-ecological model. American Journal of Health Education, 42(3), 171–180. 10.1080/19325037.2011.10599184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, & Narayanaswamy R (2019). A prediction model for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus incorporating area-level social determinants of health. Medical Care, 57(8), 592–600. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberian M, & Davis B (2019). Art therapy practices for resilient youth: A strengths-based approach to at-promise children and adolescents. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz SA, Karter AJ, Corbie-Smith G, Seligman HK, Ackroyd SA, Barnard LS, Atlas SJ, & Wexler DJ (2018). Food insecurity, food “deserts,” and glycemic control in patients with diabetes: a longitudinal analysis. Diabetes Care, 41(6), 1188–1195. 10.2337/dc17-1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs-El C (2012). Spreading the indigenous gospel of rap music and spoken word poetry: Critical pedagogy in the public sphere as a stratagem of empowerment and critique. Western Journal of Black Studies, 36(2), 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Boal A (2000). Theater of the oppressed. Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breinbauer C, & Maddaleno M (2005). Youth: Choices and change: Promoting healthy behaviors in adolescents. Pan American Health Org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland JY, Quintiliani LM, Schneider KL, May CN, & Pagoto S (2017). Social media as a tool to increase the impact of public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 107(12), 1890. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Acosta J, Carman KG, Dubowitz T, Leviton L, Martin LT, Miller C, Nelson C, Orleans T, Tait M, Trujillo M, Towe V, Yeung D, & Plough AL (2017). Building a national culture of health: Background, action framework, measures, and next steps. Rand Health Quarterly, 6(2), 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepp V (2016). Activating politics with poetry and spoken word. Contexts, 15(4), 42–47. 10.1177/1536504216685109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chittamura D, Daniels R, & Schillinger D (2020). Evaluating values-based message frames for type-2-diabetes prevention among Facebook audiences: Divergent values or common ground? Patient Education and Counseling, 103(12), 2420–2429 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clonan-Roy K, Jacobs CE, & Nakkula MJ (2016). Towards a model of positive youth development specific to girls of color: Perspectives on development, resilience, and empowerment. Gender Issues, 33(2), 96–121. 10.1007/s12147-016-9156-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croom AM (2015). The practice of poetry and the psychology of well-being. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 28(1), 21–41. 10.1080/08893675.2015.980133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demmer RT, Zuk AM, Rosenbaum M, & Desvarieux M (2013). Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus among US adolescents: Results from the continuous NHANES, 1999–2010. American Journal of Epidemiology, 178(7), 1106–1113. 10.1093/aje/kwt088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Braver N, Lakerveld J, Rutters F, Schoonmade L, Brug J, & Beulens J (2018). Built environmental characteristics and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 12. 10.1186/s12916-017-0997-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot-Campagna A, Pettitt DJ, Engelgau MM, Burrows NR, Geiss LS, Valdez R, Beckles Gloria LA, Saaddine J, Gregg EW, Williamson DF, & Narayan V (2000). Type 2 diabetes among North adolescents: An epidemiologic health perspective. Journal of Pediatrics, 136(5), 664–672. 10.1067/mpd.2000.105141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fat Company. (2018, June 4). How The Parkland Teens created a Gun-Control Movement [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7AcUTrRzoE&feature=youtu.be [Google Scholar]

- Fetters MD, Curry LA, & Creswell JW (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs: Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 pt. 2), 2134–2156. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DA, Bess KD, Tucker HA, Boyd DL, Tuchman AM, & Wallston KA (2009). Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 446–451. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Ramos MB, Trans.). Herder. (Original work published 1968). [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn AL, & McCarthy MI (2001). The genetics of Type 2 diabetes. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 15(3), 293–308. 10.1053/beem.2001.0147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guetterman TC, & Fetters MD (2018). Two methodological approaches to the integration of mixed methods and case study designs: A systematic review. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(7), 900–918. 10.1177/0002764218772641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Galloway JM, Goley A, Marrero DG, Minners R, Montgomery B, Peterson GE, Ratner RE, Sanchez E, & Aroda VR (2013). Scientific statement: Socioecological determinants of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 36(8), 2430–2439. 10.2337/dc13-1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, Chin MH, Gary-Webb TL, Navas-Acien A, Thornton PL, & Haire-Joshu D (2020). Social determinants of health and diabetes: A scientific review. Diabetes Care, 44(1), 258–279. 10.2337/dci20-0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman EC (2003). Men, dogs, guns, and cars: The semiotics of rugged individualism. Journal of Advertising, 32(1), 9–22. 10.1080/00913367.2003.10601001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim A (2020). Tupac Shakur: Spoken word poets as cultural theorists. Literary cultures and twentieth-century childhoods (pp. 255–272). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kilaru AS, Asch DA, Sellers A, & Merchant RM (2014). Promoting public health through public art in the digital age. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1633–1635. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr., Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2018). The interacting effects of psychological empowerment and ethnic identity on indicators of well-being among youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(4), 489–501. 10.1002/jcop.21953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry PL, Olster DH, Morgan GD, & Abrams DB (2008). Interdisciplinarity and systems science to improve population health: A view from the NIH Office of behavioral and social sciences research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2), S211–S224. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manresa GA, & Glăveanu V (2017). Poetry in and for society: Poetic messages, creativity, and social change. In Lehmann O, Chaudhary N, Bastos AC, & Abbey E (Eds.), Poetry and imagined worlds (pp. 43–62). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- May AL, Kuklina EV, & Yoon PW (2012). Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adolescents, 1999−2008. Pediatrics, 129(6), 1035–1041. 10.1542/peds.2011-1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J (2018). Changing the conversation. Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 6(6), 444. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30147-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, & Engelgau MM (2002). Self-management education for adults with Type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care, 25(7), 1159–1171. 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sá TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ, Edwards P, Woodcock J, Brage S, & Wijndaele K (2018). Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M (2009). “Poem is what?” Poetic inquiry in qualitative social science research. International Review of Qualitative Research, 1(4), 541–568. 10.1525/irqr.2009.1.4.541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EA, Fine S, Handley MA, Davis H, Kass J, & Schillinger D (2014). Development and early implementation of the bigger picture, a youth-targeted public health literacy campaign to prevent type 2 diabetes. Journal of Health Communication, 19(Suppl. 2), 144–160. 10.1080/10810730.2014.940476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EA, Fine SC, Handley MA, Davis HB, Kass J, & Schillinger D (2017). Engaging minority youth in diabetes prevention efforts through a participatory, spoken-word social marketing campaign. American Journal of Health Promotion, 31(4), 336–339. 10.4278/ajhp.141215-ARB-624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RE (2007). Health literacy skills of US adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(1), S8–S18. 10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, & Huey N (2018). Messengers of truth and health: Young artists of color raise their voices to prevent diabetes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 319(11), 1076–1078. 10.1001/jama.2018.0986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, & Jacobson MF (2016). Science and public health on trial: Warning notices on advertisements for sugary drinks. Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(15), 1545–1546. 10.1001/jama.2016.10516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Ling PM, Fine S, Boyer CB, Rogers E, Vargas RA, Bibbins-Domingo K, & Chou W.-y. S. (2017). Reducing cancer and cancer disparities: Lessons from a youth-generated diabetes prevention campaign. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(3 Suppl. 1), S103–S113. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Tran J, & Fine S (2018). Do low income youth of color see “the bigger picture” when discussing Type 2 diabetes: A qualitative evaluation of a public health literacy campaign. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 840. 10.3390/ijerph15050840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey HL, & Nobel J (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 254–263. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ML, Vlahov D, Hagan E, Glymour MM, Gottlieb LM, Matthay EC, & Adler NE (2019). Building the evidence on Making Health a Shared Value: Insights and considerations for research. SSM-Population Health, 9, Article 100474. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson EH (2002). Hip hop therapy: An exploratory study of a rap music intervention with at-risk and delinquent youth. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 15(3), 131–144. 10.1023/A:1019795911358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson EH (2006). Rap-music attitude and perception scale: A validation study. Research on Social Work Practice, 16(2), 211–223. 10.1177/1049731505281447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein S (2018). The room is on fire: The history, pedagogy, and practice of youth spoken word poetry. SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams CR, & Buttfield B (2016). Beyond individualised approaches to diabetes Type 2. Sociology Compass, 10(6), 491–505. 10.1111/soc4.12369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom JP, Cavaleri MA, Onwuegbuzie AJ, & Green CA (2012). Methodological reporting in qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods health services research articles. Health Services Research, 47(2), 721–745. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01344.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe J (2018). From the editor: The kids are all right: Lessons from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y-X, Xiao H-B, Wang S-S, Zhao J, He Y, Wang W, & Dong J (2016). Investigation of the relationship between chronic stress and insulin resistance in a Chinese population. Journal of Epidemiology, 26(7), 355–360. 10.2188/jea.JE20150183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet P (1999). Diabetes epidemiology as a tool to trigger diabetes research and care. Diabetologia, 42(5), 499–518. 10.1007/s001250051188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]