Dear editor

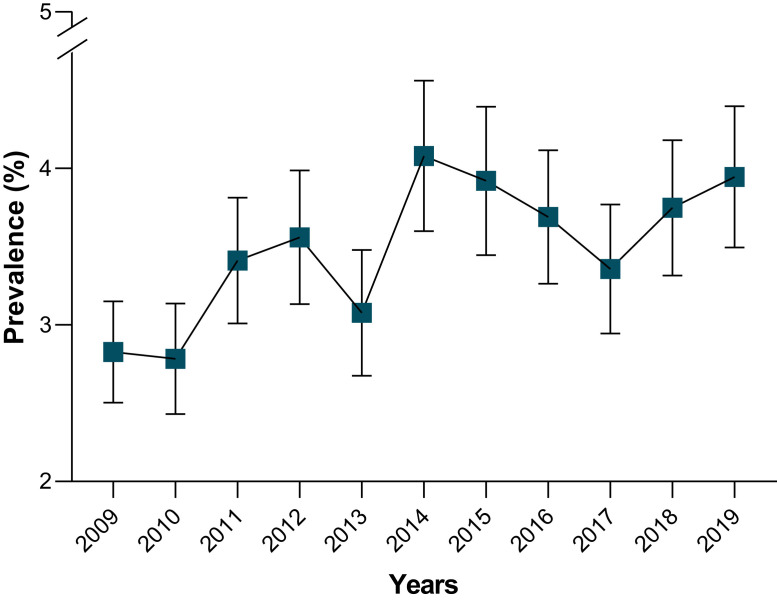

The public health burden of depression is tremendous, with over 264 million people worldwide affected. Depression can result in suicide and is also known as the second-most common cause of death in people aged 15–29 years [1]. Remarkably, South Korea has the highest suicide rate among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries [2]. A data set of 83,170 participants (45% males, mean age 41.46 ± 22.85 years) collected between 2009 and 2019 observed that the prevalence of depression was 2.83% (95%CI: 2.50%−3.15%) in 2009 and 3.93% (95%CI: 3.50%−4.40%) in 2019 (Fig. 1 and Tables S1 and S2). Growing evidence found that the prevalence of depression was high during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea (Table S3) as well as in the world [3]. We believe that the prevalence of depression was still higher compared with the most recent population-based estimates of depression in Korea because of the impact of social distancing, stay-at-home orders, and COVID-19-associated morbidity and mortality [4]. As of November 21, 2021, South Korea had recorded 347,529 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and the number of cases had been decreasing in the last few months [5]. However, successful management of the pandemic is not adequate to protect the general public from depression. This means that although the pandemic is under control, the general population is at high risk of depression. Of note, depressed patients are often not diagnosed correctly, and others who are not suffering from depression are too frequently misdiagnosed and given antidepressants [6]. Recent guidelines recommend a combination of pharmacological and psychological therapies for depression management depending on the severity of depression [7]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a prevention strategy targeting the population to slow down this progression to postpone risk factors related to depression and reduce prevalence. In this paper, we outline an overview of the key aspects of the action plan.

Table 1.

Reviewers’ comments and replies based on the journal guideline.

| No. | Comments | Replies |

|---|---|---|

| Editorial Comments: | ||

| 1. | Reviewer #1: A more detailed description of the subjects' characteristics should be presented…age range, relevant co-morbidities, etc. Gender could be reported as male (%) will do. The rest are ok | Thank you so much for taking your valuable time to leave such kind feedback. In this version, we added more information on the subject's characteristics based on your comments. In terms of relevant co-morbidities, we provided it in the supplementary data because of the limitation of number words in the letter. We hope that this version will persuade you. |

| Comments from the editorial team: | ||

| 2. | This letter begins with a summary of studies that estimated the prevalence of depression. There is a very striking increase in depression, which raises questions about how that can happen. One critical explanation can be found in Section 1.3 (Depression) in Supplementary materials: the definition for depression is not the same. “For KNHANES, depression was defined as physician diagnosis, the current presence or treatment for depression (Table 1). For data 2020, the prevalence of depression was estimated by using PHQ-9 and DASS-42.” It is very likely that this is the primary cause of the observed increase shown in the figures. A Bayesian analysis will not be able to address this without strong assumptions. Since the second part of the letter says that the frequency of depression is increasing, both separate from and because of COVID-19, it is important to detect it and treat it properly. The final paragraph then describes the national action plan. Given the problems of combining the results of different depression studies and the weak link between the first and second parts of the letter, the following is strongly recommended: - Reduce the length of the first part. The current meta-analysis is inappropriate since definitions of depression varied. If the main message of the letter is found in the second half, then convince the reader that depression needs to addressed before continuing with the second half. | Thank you so much for taking your valuable time to leave such kind comments and suggestions. In this version, we removed the systematic review and the Bayesian method. We also reduced the length of the first part. We added more information to convince readers that depression needs to be addressed. We hope this version will persuade you. |

| 3. | Grammar The manuscript currently contains many grammatical errors (including incomplete sentences). Ensure that it is properly reviewed by a native English speaker or equivalent. | Thank you very much for your valuable comments. In this version, first, we tried our best to check the grammar and structure of sentences as well as tense. Second, we sent it to our colleague to proofread. We hope that this version will meet your requirements and be better than the previous ones. |

| 4. | In addition, the title needs to be corrected. | Thank you very much for your thoughtful comments. In this version, we change it into “Action plans for depression management in South Korea came from depression survey data in 2009–2019 and during the COVID-19 pandemic.” |

| Editorial Requirements: | ||

| 5. | 1) When submitting a paper all authors must complete and sign the Authorship form downloaded from https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/HLPT.COI_Sample-1.pdf. This form confirms that all authors agree to publication if the paper is accepted and allows authors to declare any conflicts of interest, sources of funding and ethical approval (if required). a) Please download the form and submit it with your paper with the signatures from all authors. |

Thank you very much for your thoughtful guidance. In this version, we downloaded and submitted it with our manuscript. |

| 6. | 2) Please provide in-text citations for Tables S1–S3 and Fig. S1. | Thank you very much for your comments. In this version, we cited all supplementary data in the whole main text. |

| 7. | 3) In your title page, please include the following statement if it is accurate: "Patient Consent: Not required" If this statement is not correct, please amend accordingly. |

Thank you very much for your comments. In this version, we added more information about patient consent. “Patient Consent: All individuals were required to provide written informed consent prior to examinations, which were conducted by the Department of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.” |

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of depression in Korea population (n = 83,170), Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2009–2019).

The action plan addresses six core features at the national level. First, routine screening and evaluation of depression; health workers can establish plans to screen and evaluate depression conditions using the online questionnaire surveys (PHQ-9, DASS-42) on vulnerable populations such as healthcare workers, older or pregnant people, students, and people working in the hardest-hit areas [8]. These methods are fast, cheap, quick to analyze, and easy to use for participants. Second, the implementation of psychological assistance hotlines; health workers could conduct depression assessments and provide supportive counseling 24 h a day [9]. Individuals are linked to specialized healthcare facilities for proper treatment after being identified as high-risk depression groups. Third, establish community treatment (CTC) centers to prevent and control the dual effects of COVID-19 and depression [10]. Patients with minor illnesses can be cared for at the CTC, and those with severe illnesses can be transferred to hospitals. During this time, the CTC could provide psychosocial support for these patients. Fourth, depression interventions. COVID-19 can have greater psychological effects on people who already have mental problems. Therefore, early detection of depression could ensure prompt care, reduce the treatment gap, disease worsening, and the likelihood of suicide in those suffering from depression. Of note, clinicians should carefully consider the history of mental illness when managing COVID-19 patients. Fifth, encourage citizens as well as foreigners to join the national health insurance system. The cost of treating Covid-19 with comorbidities is extremely expensive, thus health insurance can help patients with this financial crisis and give them access to more health services. Finally, public education on the management of depression. It is necessary to provide appropriate information and support to the general population as well as vulnerable populations. In this context, psychiatrists, healthcare workers, and universities play a vital role in implementing timely and effective psychiatric interventions during a pandemic.

COVID-19 continues to affect the lives of people worldwide, so comprehensive public health efforts are needed to reduce depression and suicide prevalence, especially among people at high risk of depression and those with pre-existing depression but at risk of relapse.

Patient consent

All individuals were required to provide written informed consent prior to examinations, which were conducted by the Department of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author contributions

Hai Duc Nguyen: collected data and information, drafted the letter. Hojin Oh, Min-Sun Kim: commented on the draft letter. Hai Duc Nguyen, Hojin Oh, Min-Sun Kim: finalized the letter.

Funding

This work was supported by a Research Promotion Program of SCNU.

Competing interests

None declared

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the KNHANES inquiry commission and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sunchon National University as following by the guidelines set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Since 2007, this survey was conducted with the approval of the IRB of the KCDC (2009–01CON-03–2C, 2010–02CON-21-C, 2011–02CON-06-C, 2012–01EXP-01–2C, 2013–07CON-03–4C, 2013–12EXP-03–5C). KNHANES was conducted without approval from 2015 to 2019 according to the opinion of the IRB of the KCDC.

Footnotes

Health Policy and Technology

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.hlpt.2021.100575.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.WHO. Depression (www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression). Accessed Jan. 2021;12.

- 2.Lee S.U., Park J.I., Lee S., Oh I.H., Choi J.M., Oh C.M. Changing trends in suicide rates in South Korea from 1993 to 2016: a descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bueno-Notivol J., Gracia-García P., Olaya B., Lasheras I., López-Antón R., Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ettman C.K., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. e2019686-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MOHW. Coronavirus disease-19, Republic of Korea. Accessed on 21 November 2021. Available at http://ncovmohwgokr/en/.

- 6.Nguyen H.D., Oh H., Hoang N.H.M., Jo W.H., Kim M.S. Environmental science and pollution research international; 2021. Environmental science and pollution research role of heavy metal concentrations and vitamin intake from food in depression: a national cross-sectional study (2009-2017) pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M., Blanco C., Marcus S.C. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1482–1491. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park H., Yu S. Health Policy and Technology; 2020. Mental healthcare policies in south korea during the COVID-19 epidemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang E., Lee S.Y., Kim M.S., Jung H., Kim K.H., Kim K.N., et al. The psychological burden of COVID-19 stigma: evaluation of the mental health of isolated mild condition COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(3) doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.