Abstract

The clinical nurse leader (CNL) provides clinical leadership at the point of care, offers staff mentorship, assumes accountability for clinical outcomes within the microsystem, and promotes evidence-based patient care. The CNL has the skills and competencies needed to facilitate improvement science and lead care delivery redesign in the ever-changing world of health care, including in times of crisis. This article aims to detail 1 pediatric medical center's journey in utilizing the CNL to sustain high-quality patient care and promote a positive work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic using an innovative, evidence-based CNL practice model.

Key Points:

-

•

Clinical nurse leader practice may vary depending upon the practice environment.

-

•

An innovative, evidence-based clinical nurse leader practice model can lead to financial savings and improved patient care.

-

•

The clinical nurse leader can be used as a proactive tool to sustain high-quality patient care practice and maintain a healthy work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested our nation's health care system like nothing before. Although the impact it has had on our health care system, our economy, and even our society is not yet fully known, lessons have been learned to help better inform our response to health care crises in the future. One valuable lesson learned is the need to prioritize the sustainment of high quality patient care even in a national disaster. The clinical nurse leader (CNL) has the knowledge and skills necessary to provide clinical oversight and guidance to nurses, sustain evidence-based interventions, and evaluate clinical outcomes at a microsystem level, including during rapidly evolving situations challenging in our health care system.1 The CNL is skilled in improvement science and may be used by nurse executives as a proactive strategy to facilitate high-quality patient care every day and in times of crisis. This article details 1 pediatric medical center's journey in utilizing the CNL to sustain high-quality patient care and promote a positive work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic using an innovative, evidence-based CNL practice model.

The CNL Role

In 2007, in response to the Institute of Medicine's jarring 1999 report To Err Is Human, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) proposed the first new nursing role in over 35 years: the CNL.2, 3 The CNL is a master's-educated nurse tasked with providing clinical leadership at the point of care within a microsystem. The CNL assumes accountability for patient outcomes by designing, implementing, and evaluating evidence-based interventions and processes.4 As opposed to other health care quality and risk assessment roles that oversee patient outcomes system-wide, the CNL provides leadership at the clinical microsystem level, where patient care is physically occurring. A clinical microsystem is a group of people who work to provide care to a population of patients and is embedded within an organization.5 Although the AACN details 10 fundamental aspects to guide the certified CNL's practice within their microsystem (Table 1 ), data show that certified CNLs fulfill these aspects in varying ways and with varying titles.3

Table 1.

Ten Fundamental Aspects of Clinical Nurse Leader Practice

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Innovative CNL Practice Model

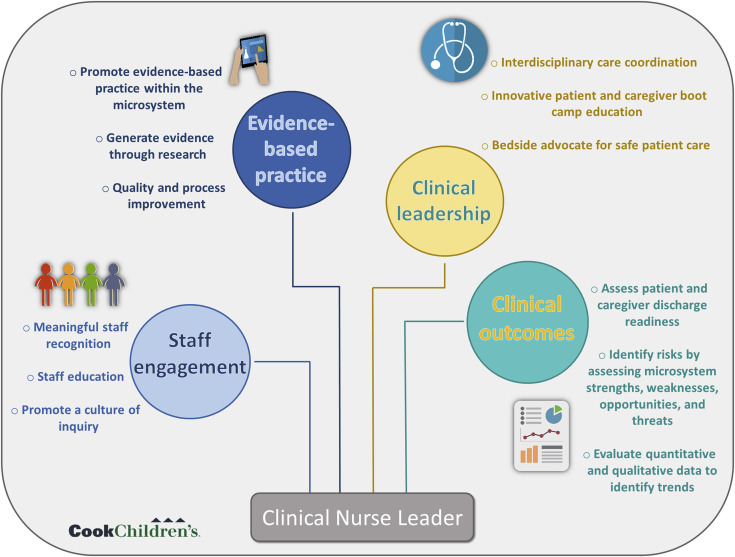

In 2017, a large urban pediatric medical center implemented the CNL role on a 26-bed inpatient transitional and rehabilitation care unit (TCU/RCU). Two full-time master’s-prepared nurses transitioned from night-shift bedside nursing positions on the unit to the CNL role. Although the AACN provides guidance to facilitate CNL work, the actual operationalization of CNL competencies was up to interpretation because each CNL practices within different clinical microsystems with varying workflows. As the first 2 certified CNLs within the medical center, these nurses reviewed literature and carefully evaluated the 10 fundamental aspects of CNL care to gather evidence to lead their CNL practice. The TCU/RCU CNLs performed a crosswalk concept analysis between the 10 fundamental elements of CNL care, CNL practice exemplars within the literature, and the workflow on TCU/RCU. The review of the literature revealed 4 themes that drive CNL care: staff engagement, evidence-based practice, clinical leadership, and clinical outcomes. These 4 themes and the crosswalk concept analysis were used to create a CNL Practice Model based upon the TCU/RCU microsystem workflow (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Cook Children's Clinical Nurse Leader Practice Model

Staff Engagement and the CNL

Meaningful connections with all clinicians within the microsystem are maintained by the CNL.10 As a master’s-prepared nurse who does not manage staff, the CNL instead acts as a mentor and role model to the team. Best clinical practices are reinforced by the CNL in real-time with nurses as patients are receiving care. CNLs advocate for integrating their role within care delivery systems and articulate the contributions of the CNL with health care team members.4 Staff engagement is highly related to work safety culture.11 Work environments that do not value the safety of staff and patients have the potential for high staff turnover and burnout.

Evidence-Based Practice and the CNL

The CNL provides leadership at the bedside to ensure evidence-based, high-quality care delivery.5 Respect for the CNL role by members of the health care team is key to its success. The CNL is not another set of hands but is a leadership strategy to incorporate evidence-based practice to improve outcomes within a microsystem of care.12 Evaluation and promotion of evidence-based practice at the point of care drive the CNL's continuous pursuit of improving patient care.4 Fiscally responsible care system improvements are designed by CNLs using current evidence.

Clinical Leadership and the CNL

The CNL protects professional nursing practice by providing evidence-based clinical leadership to produce positive patient outcomes.5 The CNL can monitor interventions as a nursing team leader, mentor at the point of care, and provide clinical leadership to ensure patient safety.5 Clinical leadership for care delivery, including the design, coordination, and evaluation of care for patients within the microsystem is assumed by the CNL.4

Clinical Outcomes and the CNL

The CNL is a crucial professional nursing strategy to address quality and safety gaps through clinical outcomes evaluation and management.13 Changes in the care delivery system to prevent patient harm are facilitated based on risk anticipation by the CNL.5 , 10 The CNL assumes accountability for clinical outcomes within the microsystem, including synthesizing evidence to improve care and achieve optimal results.4 CNL practice exemplars based on the 4 identified themes are available in Table 2 .

Table 2.

TCU/RCU CNL Practice Exemplars

| Staff engagement |

|

| Evidence-based practice |

|

| Clinical leadership |

|

| Clinical outcomes |

|

PDC, Professional Development Council.

CNL Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As the COVID-19 pandemic impacted all aspects of health care, the CNLs were tasked with maintaining a healthy work environment for staff and ensuring positive outcomes for patients. The innovative CNL Practice Model was used to guide CNL practice throughout the pandemic to sustain high-quality care during a time of crisis.

Supporting Staff Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic Exemplars

The CNLs proactively worked to prioritize a supportive work environment for nurses. Based on emerging literature during the COVID-19 pandemic that discussed concerns regarding turnover and disengagement of newly hired nurses, TCU/RCU CNLs wished to help facilitate a connection between the new nurse and the TCU/RCU team.14 The CNLs recruited each newly hired nurse to become a “super user” of a previously implemented unit-based project. This strategy facilitated early project buy-in, sustained change by creating a project super user, and assisted the new nurse to feel accountable within a team.

As the risk for compassion fatigue for nurses increased throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the TCU/RCU CNLs created a project based on the concept of compassion satisfaction.15 Compassion satisfaction is the pleasure one derives when performing their job well.16 During times of high census and critical staffing levels, compassion satisfaction can be challenging to achieve. The TCU/RCU CNLs surveyed staff to discover what leads to compassion satisfaction within their role on the unit. Themes among disciplines were identified, and interventions were created based on the feedback. One intervention was daily goal setting by charge nurses for each shift. The charge nurse would set a purposeful goal for the shift, inform the staff working that day, and follow up with the leadership team on facilitators and barriers to achieving the goal. Examples of goals were “everyone leaves their shift on time” and “everyone takes an uninterrupted 30-minute break.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, flash skills education transitioned to virtual events when possible. Virtual education strategies included a video game, an escape room, and an online scavenger hunt. Several flash skills were offered as synchronous meetings between the CNLs and staff via Zoom videoconferencing software. Hands-on skills events were provided in the hospital's simulation lab to accommodate social distancing requirements.

Professional Development Council meetings were offered virtually. The virtual meeting option strengthened the ability of the council to feature high-impact guest speakers. As the pandemic disrupted societal norms, schools were closed, and a general feeling of isolation grew, there was a dramatic increase in children with behavioral health needs being admitted to the unit.17 The TCU/RCU nurses expressed feelings of powerlessness and had questions about the ethical and legal implications of caring for these patients. The assistant general counsel of the hospital was invited to speak directly to TCU/RCU bedside nurses to ensure all questions were answered and education on care expectations was provided.

Generating Evidence During the COVID-19 Pandemic Exemplar

A challenge presented to TCU/RCU during the pandemic was a decrease in patient caregiver visitation. COVID-19–related visitor restrictions that did not allow siblings or multiple visitors in the hospital created a significant barrier for families to visit their child in the hospital. Unfortunately, this led to children with medical complexity experiencing prolonged periods of isolation. A literature review revealed a lack of evidence-based interventions to provide emotional support to children with medical complexity without family presence in the hospital. A multidisciplinary project team proposed an intervention of daily therapeutic holding for infants with medical complexity on the unit. The CNLs wrote a research proposal to determine the impact of daily therapeutic holding of infants with medical complexity as measured by ventilator days, weight and length gain velocity, and social withdrawal scores.

Sustaining Bedside Clinical Leadership During the COVID-19 Pandemic Exemplar

TCU/RCU CNLs took a proactive approach to prevent drift in high-quality patient care practices and provide clinical leadership when the unit faced critical staffing levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. A monthly Quality Surveillance Day was implemented to create a formal process to assess for drift, provide one-on-one staff education, and promote family engagement in the patient's care plan. During Quality Surveillance Day, TCU/RCU CNLs audited the chart of every patient admitted to the unit to assess for compliance to hospital-acquired infection prevention bundles of care. CNLs rounded with nurses to discuss findings at the bedside in real time as patient care was being provided. Patients and families were invited to participate in these conversations, if available. CNLs audited unit event reports, created a summarized list of events from the previous month, and determined lessons learned from each event. Results of the Quality Surveillance Day, including chart audits, one-on-one rounding, patient and family interactions, and event reports, were shared with the unit after each Quality Surveillance Day.

Sustaining Positive Outcomes During the COVID-19 Pandemic Exemplar

As meetings transitioned to a virtual format or were canceled altogether during the pandemic, a feeling of “disconnect” was initially felt among TCU/RCU leaders. Rather than abandoning the process of evaluating and reporting clinical outcomes, the CNLs created a quarterly state of the unit report to disclose unit performance in all quality metrics compared to other inpatient nursing units within the hospital. This report was shared with all microsystem staff and leaders to hold CNLs accountable for outcomes and promote transparency in microsystem performance.

The CNLs built upon the state of the unit report by creating a database for all qualitative and quantitative unit-based metrics. The CNLs used this database to write a Beacon Award for Excellence application. The Beacon Award for Excellence is awarded to inpatient clinical units that set the standard for excellence in patient care by collecting and using evidence-based information to improve patient outcomes.18 The unit received a silver-level Beacon Award of Excellence designation in 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. This award inspired the meaningful recognition of TCU/RCU staff and showcased the high-quality care provided to patients and families within a healthy work environment.

Conclusion

Although the CNL has been tasked with assuming the responsibility of improving patient care outcomes, the operationalization of CNL practice within varying microsystems is not clear.10 CNL practices must be shared, celebrated, and studied to validate and grow the CNL role. This journey by 2 certified CNLs to create an innovative CNL Practice Model was the first step in developing the CNL role within a pediatric medical center in the southwestern United States. Using this model to sustain evidence-based practice, generate evidence, and promote a healthy work environment in the face of a worldwide pandemic validates the relevancy of the model and the CNL. Nurse executives should consider the CNL as a tool to improve patient outcomes and create a healthy work environment for nurses in the chaotic, ever-changing world of health care.

Biography

Julie Van Orne, MSN, RN, CPN, CNL, is a Clinical Nurse Leader at Cook Children’s Medical Center in Fort Worth, Texas. She can be reached at julie.vanorne@cookchildrens.org. Kaylan Branson, MSN, RN, CPN, CNL, is also a Clinical Nurse Leader at Cook Children’s Medical Center.

Footnotes

Note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cook Children’s Medical Center.

References

- 1.Hoffman R., Battaglia A., Perpetua Z., Wojtaszek K., Campbell G. The clinical nurse leader and COVID-19: leadership and quality at the point of care. J Prof Nurs. 2020;36(4):178–180. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn L., Corrigan J., Donaldson M., Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C., United States: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavo-Hall J.A., Bender M., Harvath T.A. Roles enacted by clinical nurse leaders across the healthcare spectrum: a systematic literature review. J Prof Nurs. 2018;34(4):259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Association of Colleges of Nursing Competencies and curricular expectations for clinical nurse leader education and practice. 2013. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/News/White-Papers/CNL-Competencies-October-2013.pdf Available at:

- 5.Rankin V. Clinical nurse leader: a role for the 21st century. Medsurg Nurs. 2015;24(3) 199-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Orne J. Implementation of a nurse-driven pediatric bowel management algorithm: a quality improvement project. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;61:224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gesinger S. Experiential learning: using Gemba walks to connect with employees. Prof Saf. 2016;61(2):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Orne J., Branson K., Cazzell M. Boot camp for caregivers of children with medically complex conditions. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2018;29(4):382–392. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2018873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry J.G., Ziniel S.I., Freeman L., et al. Hospital readmission and parent perceptions of their child's hospital discharge. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(5):573–581. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bender M. Conceptualizing clinical nurse leader practice: an interpretive synthesis. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(1):E23–E31. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press Ganey Reverse the trend: improving safety culture in the COVID-19 era. 2021. https://www.pressganey.com/resources/white-papers/reverse-trend-improving-safety-culture-covid-19-era Available at:

- 12.Hodge M.A. The impact of the clinical nurse leader (CNL) on quality patient outcomes. S C Nurse (1994) 2017;24(1):10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender M., Williams M., Su W., Hites L. Refining and validating a conceptual model of clinical nurse leader integrated care delivery. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(2):448–464. doi: 10.1111/jan.13113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Nurses Foundation Pulse of the Nation's Nurses Survey Series: Mental Health and Wellness Survey 1. 2020. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/mental-health-and-wellbeing-survey/ Available at:

- 15.Thew J. COVID-19 creates vicarious trauma among healthcare workforce...Ellen Fink-Samnick. Healthcare Leadersh Rev. 2020;39(8):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varadarajan A., Rani J. Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction and coping between male and female intensive care unit nurses. Indian J Posit Psychol. 2021;12(1):49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartek N., Peck J.L., Garzon D., VanCleve S. Addressing the clinical impact of COVID-19 on pediatric mental health. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35(4):377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Association of Critical Care Nurses Beacon Award of Excellence. 2020. https://www.aacn.org/nursing-excellence/beacon-awards Available at: