Abstract

Purpose

To present first highly spatially resolved deuterium metabolic imaging (DMI) measurements of the human brain acquired with a dedicated coil design and a fast chemical shift imaging (CSI) sequence at an ultrahigh field strength of B0 = 9.4 T. 2H metabolic measurements with a temporal resolution of 10 min enabled the investigation of the glucose metabolism in healthy human subjects.

Methods

The study was performed with a double-tuned coil with 10 TxRx channels for 1H and 8TxRx/2Rx channels for 2H and an Ernst angle 3D CSI sequence with a nominal spatial resolution of 2.97 ml and a temporal resolution of 10 min.

Results

The metabolism of [6,6′-2H2]-labeled glucose due to the TCA cycle could be made visible in high resolution metabolite images of deuterated water, glucose and Glx over the entire human brain.

Conclusion

X-nuclei MRSI as DMI can highly benefit from ultrahigh field strength enabling higher temporal and spatial resolutions.

Keywords: DMI, Deuterium, Human brain, 9.4 Tesla, Oral glucose administration, TCA cycle

1. Introduction

Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI/2H MRSI) is a novel non-invasive technique to investigate metabolic pathways using Deuterium (2H) labeled tracers (De Feyter et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016). The water natural abundance of 2H is very low (> 0.015% before and 0.0115% after correction for tissue water fraction) (Zhu and Chen, 2018; De Feyter and de Graaf, 2021), which makes it very suitable for the application as a tracer. Different potential applications of 2H MRS were already investigated in animal models, including chemotherapy response (Kreis et al., 2020), Alzheimer's disease (Chen et al., 2021), adiposity (Riis-Vestergaard et al., 2020), visibility of liver glycogen (HM De Feyter et al., 2021) and monitoring of tumor cell death (Hesse et al., 2021). Especially in cancer research, the application of deuterated glucose to investigate the glycolytic flux as well as the Warburg effect seems very promising, which was shown for animal models as well as human patients (De Feyter et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016; Kreis et al., 2020). The most prominent 2H tracer used in previous studies is [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose which allows for the investigation of the TCA cycle.

The metabolic pathways leading to 2H label incorporation into downstream metabolic products of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose are illustrated in previous publications of de Feyter et al. and Lu et al. (De Feyter et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2017) (see supplemental material figure S1 for an adopted illustration). As a first step, the DMI detectable [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose enters glycolysis and is converted to pyruvate. In the healthy human brain, pyruvate is not DMI detectable (Albers et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2013). Pyruvate is transported into mitochondria as substrate for the TCA cycle (Lu et al., 2017) and excess pyruvate is in a dynamic chemical equilibrium with DMI detectable lactate via lactate dehydrogenase . In the mitochondria, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA via pyruvate decarboxylation. Acetyl-CoA enters the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle and is converted in the intermediates citrate and α-ketoglutarate. The latter can exchange with glutamate, which can be converted to glutamine. Glutamine and glutamate are detectable with DMI. From the TCA cycle, also deuterated water can be produced which is also visible with DMI. Different metabolic flux rates can potentially be investigated with DMI, enabling a multitude of potential applications. In healthy human subjects, the main detectable components are deuterated water, glucose and Glx (combined resonance of deuterated glutamate and glutamine). In tumor tissue, lactate is a dominant resonance of the 2H spectrum (De Feyter et al., 2018).

The metabolism of glucose in different tissue types (e.g. tumor tissue) can also be investigated using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) (Fukuda et al., 1982). Compared to FDG-PET, DMI has the very important advantage of applying a stable isotope. No radioactive radiation exposure is required. In addition, DMI enables the separate detection of multiple processes as glucose transport, glycolysis and TCA cycle. Another alternative to investigate the glycolytic pathway is 13C-labeled MRS. De Graaf et al. (de Graaf et al., 2020) showed in a recent publication that 2H MRS as a twice as high experimental sensitivity compared to non-hyperpolarized 13C-labeled MRS.

Nevertheless, DMI has a low sensitivity due to the low gyromagnetic ratio. The sensitivity can be improved by using higher magnetic fields B0 (de Graaf et al., 2020; Ladd et al., 2018). Due to the low sensitivity of DMI, earlier publication on DMI showed only static DMI acquisitions for the glucose uptake in the human brain with a relatively low spatial resolution of 8 ml for full brain coverage of human subjects measured at 4T and 7T (De Feyter et al., 2018; de Graaf et al., 2020).

The purpose of this work is to demonstrate the SNR advantage of a ultrahigh field strength of 9.4 T that enable dynamic DMI measurements of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose uptake of the healthy human brain with a high temporal (10 min) and spatial resolution (2.96 ml) that has so far not been achieved. A dedicated dual-tuned 1H/2H array coil design was used, which enables imaging of the entire brain with high SNR. Highly temporally and spatially resolved whole-brain images of the metabolic uptake of deuterated glucose and label incorporation into downstream metabolites (water and Glx) over the entire human brain of healthy subjects are presented. A proof-of-principle analysis of the 2H label uptakes reflecting oxidative metabolism in different brain tissue types was performed for the first time.

2. Methods

All data was acquired at a Siemens Magnetom 9.4 T whole body human magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). The vendor implemented, image-based second-order B0 shimming was applied. All experiments with volunteers were approved by the local ethic committee. All volunteer data was acquired after written informed consent. In total, 12 volunteers participated in this study (T1 measurement: n = 4, non-localized 2H MRS: n = 2, 2H MRSI: n = 7; one volunteer participated in the T1 measurement and the 2H MRSI).

2.1. Radiofrequency coil design

All experiments were performed with a double-tuned phased array radiofrequency (RF) coil (see Fig. 1A). The RF coil consists of 10 TxRx channels for proton (1H) and 8TxRx/2Rx channels for deuterium (2H). The design of the 2H/1H coil resembles a double-tuned 31P/1H phased array coil presented in an earlier publication (Avdievich et al., 2020). Therefore, the performance of the proton array is comparable to the previous 31P/1H array and only the performance of the 2H array is presented in this publication.

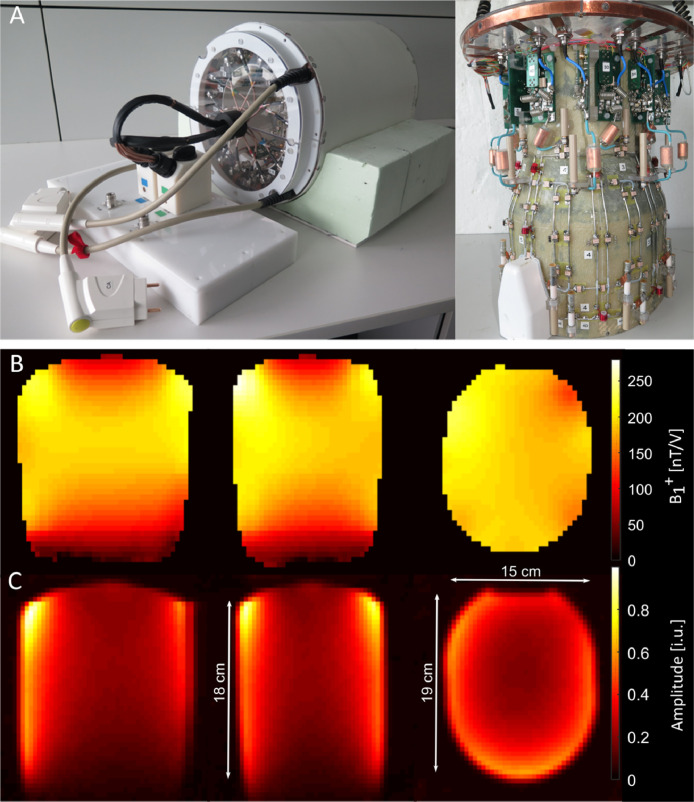

Fig. 1.

Coil design and corresponding 2H B1 distribution of a phantom measurement. The first row (A) shows the design of the 2H/1H double-tuned RF coil. Below the transmit field B1+images for the 2H channels of the double resonant 2H/1H phased array coil measured at a phantom are shown (B; length of the phantom 18 cm; axis of 19 cm x 15 cm). Below, 2H signal amplitude images of the same phantom are shown (C). The signal amplitudes are given in [i.u.].

For testing of the 2H coil performance, an elliptical phantom with a rounded top (length 18 cm, axes of ellipse 19 cm x 15 cm) containing water mixed with deuterated water (4%) was used. To match the electro-magnetic conditions of the human brain, 7.14 g NaCl and 632.7 g sucrose was added per liter of water. The measured permittivity ε was 53.83 and the conductivity σ is 0.0992 S/m at 60 MHz5.

B1+mapping was performed with a phase-sensitive sequence with spiral readout (Mirkes et al., 2016; Allen et al., 2011) with the following parameters: 48 slices, slices thickness 5 mm, FoVx/y = 220 mm, TR = 1.5 s, TE = 1.23 ms, flip angle = 206 deg, one average, number of samples on spiral 448, resolution 5 mm, spiral arms = 19 and rectangular excitation pulse with a pulse duration of 1 ms.

In addition, the signal amplitude distribution was measured in the phantom with the same spiral readout imaging sequence and the following sequence parameters: 52 slices, slices thickness 4 mm, FoVx/y = 200 mm, TR = 300 ms, TE = 0.3 ms, flip angle = 25 deg, one average, number of samples on spiral 448, resolution 4 mm, spiral arms = 19 and rectangular excitation pulse with a pulse duration of 1 ms.

2.2. Scanner configuration

Deuterium is not supported by the standard scan software available for Siemens whole body imaging systems. Therefore, the frequency needs to be generated externally by a signal generator (Hartmann et al., 2021) (EXG Analog Signal Generator, NS171B, 9 kHz – 3 GHz, Agilent). A frequency of 59.673 MHz with a corresponding amplitude of 8 dBm was split up to one transmit board and three receive boards of the Siemens whole body imaging system. The selected nucleus by the scanner software was 17O. SAR simulations as well as test measurements were performed in accordance to the local RF coil safety protocol.

2.3. Estimation of T1 times

To optimize SNR of the in vivo 2H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (2H MRS) and spectroscopic imaging (2H MRSI / DMI) measurements, the T1 relaxation times for deuterated water were acquired for four different volunteers. Hereby, the natural abundant signal of deuterated water in the brain was measured. A non-localized inversion recovery sequence with an adiabatic FOCI pulse (Pohmann et al., 2018; Ordidge et al., 1996) with the following parameters was used: TR = 4 s, pulse duration rectangular excitation pulse 0.5 ms, acquisition delay 0.35 ms, vector size 2048, averages 20 and pulse duration FOCI pulse 8 ms. Fifteen different inversion times (TInv) logarithmically distributed between 10 ms and 2512 ms were measured. The resulting amplitudes were fitted in Matlab R2018a (MATLAB, The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) using the curve fitting toolbox (De Graaf, 2008):

| (1) |

Hereby, A is a scaling factor given in [i.u.], TInv are the acquired inversion times and c is a constant offset.

2.4. Imaging of dynamic metabolic uptake

All in vivo glucose experiments were performed with an oral administration of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose (purity ≥ 99.0%). The glucose was ordered from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Taufkirchen, Germany). All volunteers were asked not to eat 9 h before the start of the experiment. Only healthy volunteers participated in the measurements. For each volunteer, 0.75 g/kg body weight of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose was dissolved in 150 ml to 200 ml drinking water. The blood sugar of each volunteers was measured with an Accu-Check Aviva before and after the measurement, using capillary blood from the fingertip (for the measured blood sugar levels see supplement material Tab. S1).

2.4.1. 2H FID MRS - whole brain dynamic glucose uptake

For two volunteers, non-localized FID measurements of the brain were performed in preparation of the spatially resolved DMI measurements to estimate the required temporal resolution of the dynamic 2H MRSI protocol. The non-localized measurements had a temporal resolution of 2 min. The following sequence parameters were applied: TR = 1 s, averages 120, vector size 1024, acquisition bandwidth 3 or 2 kHz and 90 deg hard excitation pulse (Tp = 0.5 ms). For one volunteer, a reference measurement was performed prior to the administration of glucose. The first measurement was started after 11 / 5 min and the last measurement ended after 129 / 117 min for the first / second volunteer respectively.

2.4.2. 2H MRSI data acquisition - localized dynamic glucose uptake

A fast Ernst angle 3D MRSI sequence was used for dynamic 2H metabolic imaging. The following parameters were applied (Mirkes et al., 2016): FoV (180 × 200 × 180) mm3, grid size (12 × 13 × 14), TR = 155 ms, 11 averages, Hanning weighting, rectangular pulse with Tp = 0.5 ms, flip angle = 51 deg, vector size 512, 20 preparation scans and acquisition bandwidth 5000 Hz. The temporal resolution of this measurement is 10 min. The Ernst angle was calculated using the measured T1 relaxation times of deuterated water. In addition, a 3D MP2RAGE (spatial resolution (1 mm)3, flip angle = 4/7 deg, TE = 2.27 ms, TI = 750/2100 ms, TR = 6 ms, volume TR = 5.5 s) was acquired for anatomical imaging and tissue segmentation (Hagberg et al., 2017). For B1+correction of the MP2RAGE image, actual flip angle imaging (AFI) was acquired with the following parameters: TR1 = 20 ms, TR2 = 100 ms, TE = 4 ms and flip angle 60 deg. Consistent 2H MRSI, MP2RAGE and AFI data were acquired before the oral administration of 2H-labeled glucose. Twelve more 2H MRSI were acquired afterwards. After acquiring the anatomical images as well as the 2H MRSI reference measurement, the volunteers were moved out of the scanner bore while asked to stay in the supine position. Afterwards, the glucose solution was administered in the supine position and the volunteer was moved back into the scanner bore. Seven volunteers participated in this part of the study.

2.4.3. 2H MRS / MRSI data evaluation

Post-processing of the non-localized 2H MRS included zero-filling to twice the spectral resolution. Post-processing of the 2H MRSI data included the following steps: 3D Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT), WSVD (whitened singular value decomposition) coil combination according to literature (Bydder et al., 2008; Rodgers and Robson, 2010), 40 Hz Gaussian time domain filter, zero-padding to twice the spatial resolution and zero-order-phase correction. The zero-order phase was calculated by maximizing the integral of the real part of the deuterated water resonance in the spectral domain.

All 2H MRS / MRSI data were quantified by a self-implemented version of the AMARES algorithm (Vanhamme et al., 1997), which was implemented in Matlab R2018a. The spectral fitting is hereby performed on the time domain signal. A Lorentzian line shape was used. Prior knowledge about starting points for resonance frequencies and linewidth were included in the fit. The starting points for the 2H MRSI data were estimated from a fit of the averaged spectra over the entire brain prior to the quantification of the voxel-wise spectra. Soft constraints for the linewidth were used (maximum: estimated starting value plus 50 s−1). The first-order phase was included in the fit and fixed to 0.66 ms. One zero-order phase for all resonances was fitted per spectrum.

The 2H MRSI signal amplitudes were normalized by a reference water measurement of the naturally abundant deuterated water signal. This reference measurement was acquired before the oral administration of 2H-labeled glucose. Due to this normalization, the 2H MRS / MRSI data were automatically corrected for inhomogeneity of the receive sensitivity (B1−) of the deuterium RF coil .

2.4.4. Tissue type specific analysis

The uptake of 2H labeling into metabolites downstream of glucose was investigated for different areas of the brain. To achieve this, a tissue type segmentation was performed based on the MP2RAGE measurement. We used the SPM12 algorithm (Penny et al., 2006) to assign each MP2RAGE voxel to a certain tissue type. A self-implemented python algorithm was used to co-register the MP2RAGE data to the MRSI grid (Python version 2.7). Subsequently, the tissue fractions per 2H MRSI voxel for white matter (WM), gray matter (GM), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the skull were calculated.

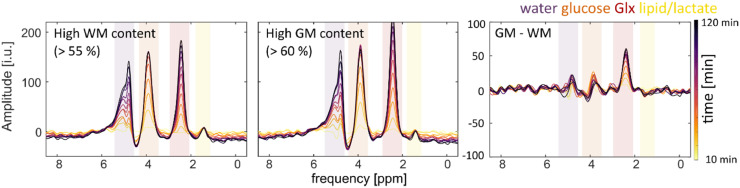

With the calculated brain tissue type fractions, tissue masks were calculated. A voxel was labeled as white matter if it contained at least 55% white matter and less than 12% CSF. Gray matter voxel consist of at least 60% gray matter and not more than 12% CSF. Summed spectra over GM and WM were calculated for each individual volunteer and signal amplitudes were estimated for water, glucose and Glx for each of these spectra. These averaged spectra were fitted and labeling uptake curves were presented for water, glucose and Glx. As a visual aid, curves were fitted to the labeling uptakes (a linear model for water, bi-exponential for glucose and mono-exponential for Glx).

Difference spectra averaged over all volunteers were calculated for gray and white matter voxel. Prior to averaging, all spectra were zero- and first-order phase corrected as well as frequency aligned to the water resonance. Zero-padding was performed to eight times the original spectral resolution. In addition, all spectra were corrected for 2H receive sensitivity B1− by dividing them by the voxel specific fitted 2H reference water signal peak area. Difference spectra were calculated within gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) between individual time points after the oral administration of deuterated glucose and the respective reference measurement before the intake of deuterated glucose. In addition, difference spectra between gray matter and white matter for all individual time points after the oral administration of deuterated glucose were calculated. The summed GM spectra over all volunteers contain 63% pure GM, 27% WM, 8% CSF and 2% skull (number of voxel: 309). The summed WM spectra contain 35% pure GM, 58% WM, 6% CSF and 0% skull tissue (number of voxel: 780).

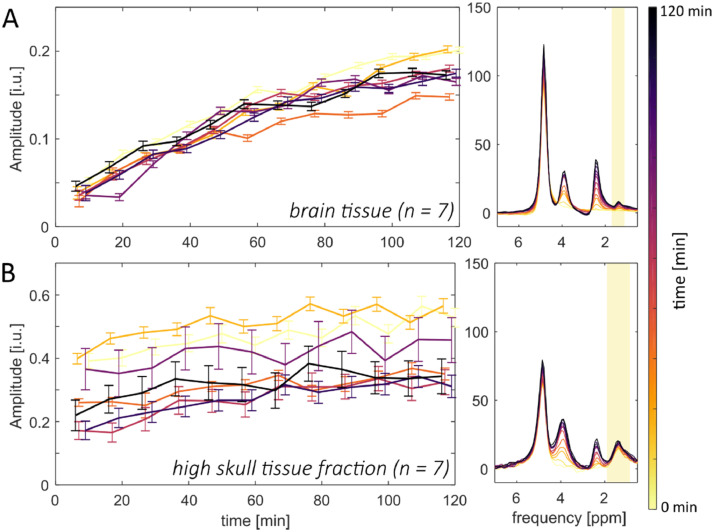

To investigate the origin of the resonance around 1.4 ppm in the 2H MR spectrum more closely, averaged spectra for each volunteer and time point were calculated from all voxel inside the brain (CSF plus WM plus GM tissue fraction > 99%) and compared to averaged spectra with a high skull tissue fraction (average skull fraction of the voxel for each volunteer: (21 ± 6)%). Signal amplitudes for the resonance at 1.4 ppm were estimated for the brain spectra and the skull spectra and the labeling uptakes were presented.

3. Results

3.1. Coil design

Fig. 1B shows the 2H B1+transmit field of the circular polarized (CP) mode. The transmit field is homogenous (mean and SD over central slice (188 ± 15) nT/V) and strongest in the central area reaching approximately B1+ = 190 nT/V. This transmit field distribution is expected due to a low transmit frequency of 61.357 MHz and transmit elements surrounding the phantom or head while being driven in the CP mode. Similar results have been shown before in Avdievich et al. (Avdievich et al., 2020) for 31P in an equivalent 31P/1H double-tuned coil design. Due to the homogeneous transmit field, no B1+field correction needs to be applied to the 2H metabolite images.

The overall receive signal distribution of the 2H coil array for the phantom measurement is shown in Fig. 1C. The signal is higher closer to the coil elements and lower in the center of the phantom as expected for a phased array coil. The receive signal amplitude distribution is expected to be dominated by the receive field B1−. Therefore, the difference between the signal amplitudes in the center and close to the receive elements are stronger for higher numbers of smaller receive elements. The herein presented 2H/1H coil array can be seen as a trade-off between the gain in SNR close to the coil elements and a still relatively small SNR gradient to the center.

Proton transmit and receive fields of the herein utilized 2H/1H transceiver coil array resemble the ones shown in a previous publication of Avdievich et al. (Avdievich et al., 2020) for an equivalent 31P/1H double tuned coil array design.

3.2. T1 relaxation times

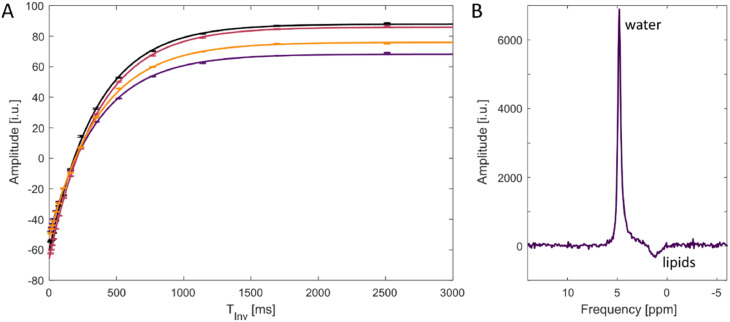

The fitted curves are shown in Fig. 2A as well as a representative spectrum from a single time point and volunteer (Fig. 2B). The calculated mean value for the T1 relaxation time aver all volunteers was (361.8 ± 6.4) ms. The corresponding error was calculated by Gaussian propagation of uncertainty from the 95% confidence intervals of the T1 relaxation times estimated from individual volunteers. The major signal contribution in Fig. 2B arises from the natural abundant deuterated water. Next to the water signal, another resonance is visible, which most likely arises from different lipid contribution, as known from non-lipid suppressed proton MRS.

Fig. 2.

Measurement of T1 relaxation times. Shown are the measured amplitudes of the water resonance with fitted relaxation time curves for all measured volunteers (n = 4) (A) as well as a representative spectrum acquired at a single time point from one volunteer (B). The T1 measurement was performed with a non-localized inversion-recovery sequence.

3.3. Imaging of dynamic metabolic uptake

Oral intake of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose leads to incorporation of 2H labeling into the downstream metabolites glucose, lactate, water and Glx (combined resonance of glutamate/glutamine) (see also supplement material figure S1), which can thus be detected with deuterium MR spectroscopy (De Feyter et al., 2018).

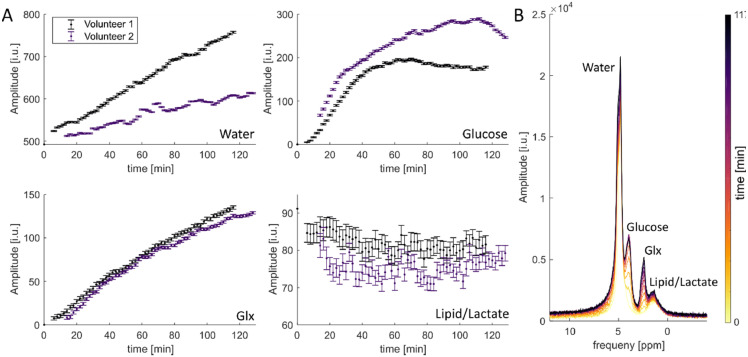

3.3.1. FID MRS - whole brain dynamic glucose uptake

Fig. 3B shows the non-localized whole brain 2H spectra of one volunteer measured for different time points after the oral administration of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose. Four resonances are detectable. Three of the resonances can be assigned to deuterated water, glucose and Glx. The fourth resonance is in the ppm range of lactate (De Feyter et al., 2018). Nevertheless, as lactate should be low in healthy brain tissue and as this resonance occurs in the natural abundance measurement as well (Fig. 2C); the resonance stems more likely from lipid contributions.

Fig. 3.

Non-localized 2H MRS with high temporal resolution. For two different volunteers, signal amplitudes with a temporal resolution of 2 min were measured with a non-localized FID pulse acquire sequence. Detectable 2H metabolites are water, glucose and glutamate/glutamine (Glx). In addition, a fourth peak is visible which can be assigned mainly to lipid contaminations. A shows the amplitude-time curves for the four resonances for all three volunteers. The presented errors are calculated as Cramer-Rao lower bounds. B shows exemplary spectra for different time points for the volunteer.

The changes in signal amplitudes for all four resonances and two different volunteers after the oral administration of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose are shown in Fig. 3A. An almost linear increase in signal amplitude is visible for water and glutamate/glutamine (Glx). The deuterated glucose signal increases very rapidly after the administration of the 2H-labeled glucose and seems to stay relatively stable or decrease afterwards. The resonance that was assigned to lipids/lactate is relatively stable for the acquired time range. The errors were calculated using CRLBs (Cramer-Rao lower bounds).

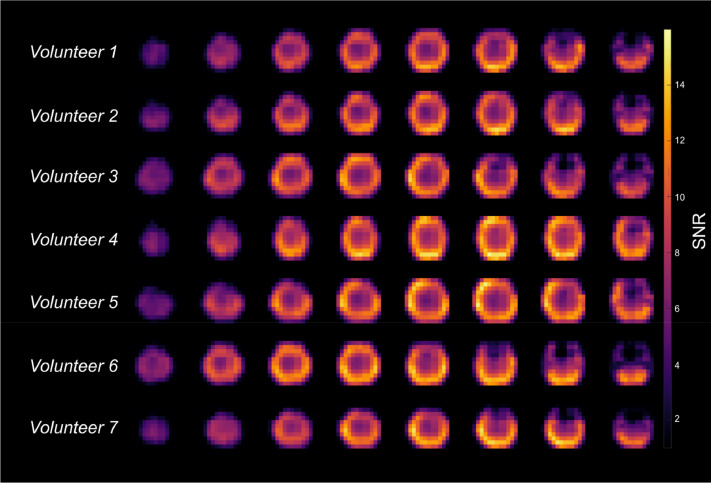

3.3.2. MRSI - localized dynamic glucose uptake

The in vivo signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the water resonance measured during the reference measurement is shown in Fig. 4 for all seven volunteers. SNR is defined as the fitted signal amplitude in the time domain divided by the standard deviation of the time domain signal from a voxel outside of the human head. No post-processing beside FFT, averaging and coil combination was applied to calculate the SNR images. In the periphery, the SNR is around 13. In the center, the measured SNR is around 5.5. Comparing the in vivo images in Fig. 4 with the phantom measurement in Fig. 1B, it is evident that the higher SNR in the periphery is mainly the result of the coil sensitivity profile.

Fig. 4.

In vivo SNR distributions. Seven different volunteers were measured with the MRSI protocol. Shown are the corresponding SNR maps for the natural abundant water signal for different transversal slices for all volunteers. SNR was calculated as the fitted signal amplitude in the time domain divided by the standard deviation of the time domain signal from a voxel outside of the human head.

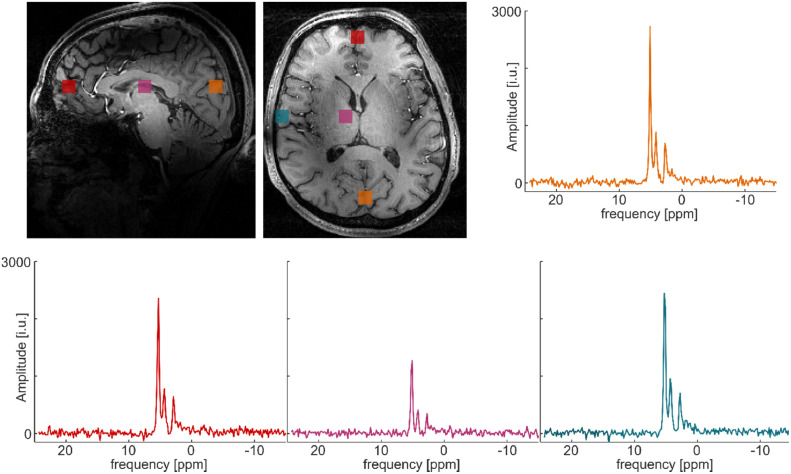

Fig. 5 shows representative spectra for individual 2H MRSI voxels from one volunteer and four different locations. The locations are encoded with different colors in the anatomical image. No spectral filtering was applied for the shown spectra. Again, the receive sensitivity gradient of the 2H coil is visible. In the center of the brain, the signal is lower compared to the periphery. Water, glucose and Glx resonance lines are clearly visible in the 2H spectra from all four voxels. The fourth resonance is only visible in the spectra located close to the skull. This finding supports the hypothesis that this resonance mainly stems from lipid contributions. In supplemental Figure S2, MRS images of the fourth resonance and different slices are shown for one volunteer. The signal of this resonance appears as a ring around the head, which further supports the assumption that this resonance consists mainly of lipid contributions.

Fig. 5.

Exemplary in vivo spectra. Four different spectra from a single volunteer from positions indicated in the anatomical image in the left upper corner are presented. The shown spectra were measured approx. 90 min after administration of 2H-labeled glucose.

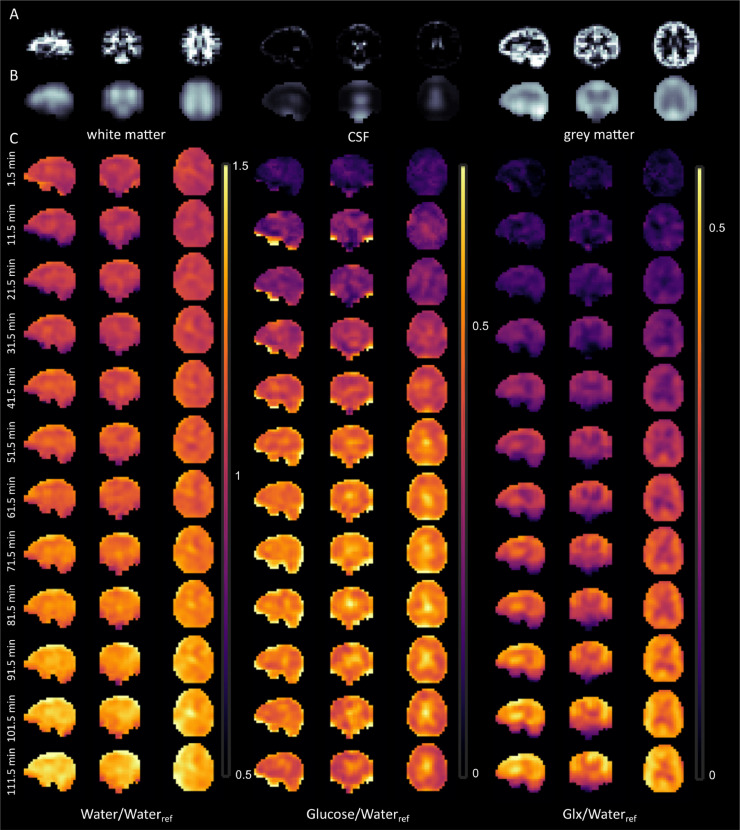

Time-resolved 2H MRS images of deuterated water, glucose and Glx are shown in Fig. 6, Fig. 7. Slices from all three directions (sagittal, coronal and transversal) are presented for the data acquired from one representative volunteer (Fig. 6). Fig. 6A shows the corresponding brain tissue type segmentation results with the spatial resolution of the original MP2RAGE images. In Fig. 6B, these segmentation results were spatially down sampled by applying the PSF of the DMI data to reflect the tissue type composition of individual voxels at the respective lower resolution. In Fig. 6C, the 2H MRS images normalized to the natural abundance deuterated water measurement are presented for three resonances (water, glucose and Glx). Especially for glucose and Glx, a brain tissue type dependence of the 2H label uptake can be identified in the 2H MRS images. By comparing the low resolution segmentation results to the metabolite maps, a strong increase of deuterated Glx signal over time can be seen in the gray matter (Fig. 6C) . In contrast, deuterated Glc is more evenly distributed across gray and white matter, but accumulates in the CSF. Finally, deuterated water does not show a strong anatomical contrast.

Fig. 6.

Temporal resolved DMI of a single volunteer and sagittal, coronal and transversal direction. The first rows show the white matter, CSF and gray matter fractions without (A) and with (B) accounting for the point-spread function (PSF). In C, the DMI maps for water, glucose and Glx are shown. All metabolite images were normalized by the natural abundant water signal. At the left side, the begin times of the DMI measurement are stated. The images were zero-filled to two times the original resolution. The amplitudes are given in relative units [i.u.]/ [i.u.] = 1.

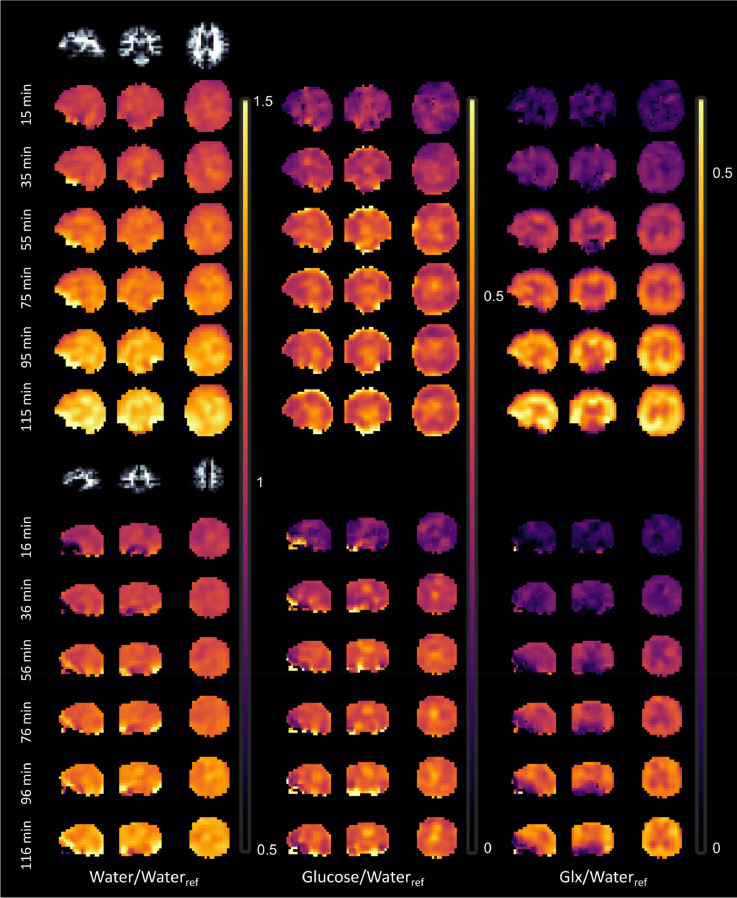

Fig. 7.

Temporal resolved DMI for different volunteers. Shown are the 2H metabolic maps of water, glucose and Glx relative to the water reference measurement for two different volunteers and different time points (skipping every other; the starting time of the 2H MRSI measurement are given). The images were zero-filled to two times the original resolution. The amplitudes are given in relative units [i.u.]/ [i.u.] = 1.

Fig. 7 shows equivalent 2H metabolic images for the 2H water, glucose and Glx for two more volunteer for every second DMI acquisition. The images show identical patterns for all the metabolites compared to the volunteer shown in Fig. 6.

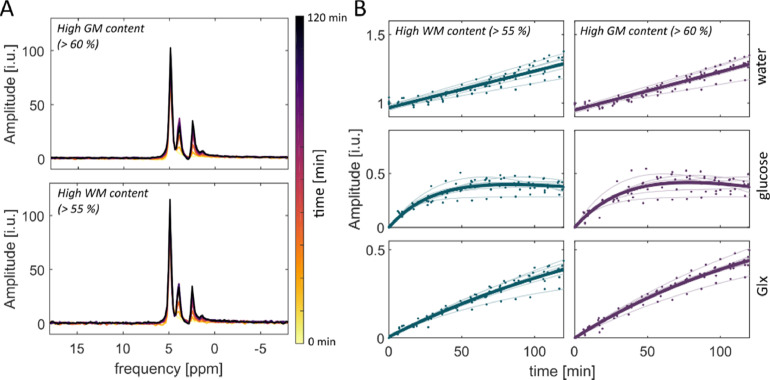

3.3.3. Tissue specific analysis and difference spectra

Tissue type specific spectra for WM and GM tissue were calculated. Exemplary results for one volunteer are shown in Fig. 8A. Before the oral administration (t = 0 min equals the reference measurement), only the natural abundant 2H water resonance is visible in WM and GM. Fig. 8B shows fitted amplitudes for all time points and volunteers. As a visual aid, model curves were fitted to the 2H water, glucose and Glx amplitudes for individual volunteers (transparent) as well as for the data points from all volunteers (n = 7, bold).

Fig. 8.

2H metabolic signal uptake in GM and WM. The left side (A) shows the signal uptake spectra for one volunteer summed over all voxel with either WM or GM content. The left side (B) shows the measured amplitudes from the summed tissue specific voxel for WM and GM for all volunteers as well as fitted curves for all volunteers (n = 7) individually as well as fitted through all data points (bold). For water, a linear model used. For glucose, a bi-exponential fit was applied (f(t) = A1 exp(- k1 t)) – A2 + (A2 – A1) exp(-k2 t)) and for Glx, a mono-exponential function was fitted to the data points (g(t) = A1 - (A1 – A2) exp(-k t)).

Fig. 9 shows the summed difference spectra across all volunteers (n = 7) for summed voxels with a high WM and GM content. The first two graphs show the difference spectra for the different tissue types at different time points relative to the reference measurement that was acquired before the oral administration of 2H-labeled glucose. The uptake of 2H-labeled water, glucose and Glx is clearly visible . The third graph shows the differences in metabolite uptakes between gray matter and white matter. Glx shows a higher uptake in GM compared to WM rich tissue. GM seems to have a higher level of glucose and water compared WM. Glucose seems to be higher in GM for the first time points, but seems to decrease faster in GM compared to WM. No changes seem to appear in the lipid/lactate ppm range.

Fig. 9.

Difference spectra of tissue with a high content of white matter (WM) and gray matter (GM) for the different measured time points after the oral administration of deuterated glucose relative to the reference measurement before the administration of labeled glucose. The third image shows the relative difference in the uptake of the different 2H-labeled metabolites between different voxels with a high GM and WM content at different time points. The difference spectra are summed spectra over all volunteers (n = 7).

Fig. 10 shows on the right side the averaged spectra for one volunteer for voxels inside the brain (A) and voxels with a high skull tissue fraction (B). On the left side, the corresponding labeling uptakes of the resonance around 1.4 ppm are shown. The spectra inside the brain do not contain any signal at 1.4 ppm before the oral administration of 2H-labeled glucose (t = 0 min). After the oral administration of glucose, a resonance becomes visible in this ppm-range. The corresponding signal amplitude increases over time. For the averaged spectra with high skull tissue fraction, a strong resonance around 1.4 ppm is visible before the oral administration of labeled glucose. The signal of this resonance shows only a small increase over time. This further supports the hypothesis of overlapping lactate and lipid resonances in this ppm-range.

Fig. 10.

Signal evolution of the resonance at 1.4 ppm. The upper row (A) shows the estimated signal amplitudes of the 1.4 ppm resonance for averaged voxels over from inside the brain for all volunteers (n = 7) and different time points as well as exemplary averaged spectra for different time points from a single volunteer. The lower row (B) shows the corresponding signal amplitudes and spectra for tissue with a high skull tissue fraction.

4. Discussion

We present highly spatially and the first temporally resolved 2H magnetic resonance spectroscopic images acquired from the healthy human brain at an ultrahigh field strength of 9.4 T with a dedicated 2H/1H transceiver array coil. The spatial distribution of the dynamic [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose uptake and the 2H label incorporation into corresponding metabolic products was observed over the entire brain of healthy human subjects. Brain energy metabolism differences between gray matter and white matter and enrichment of glucose in CSF could be visualized for the first time.

Former publications of 2H-labeled glucose metabolic flux at the brain mainly included animal experiments (Kreis et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2017; Rich et al., 2020; de Graaf et al., 2021). Only a very limited number of experiments were conducted on the human brain (De Feyter et al., 2018; de Graaf et al., 2020). These publications presented a relatively low nominal spatial resolution of 8 ml in a measurement time of 29 min for whole-brain coverage acquiring steady-state metabolic images, which do not allow for the investigation of the glycolytic flux of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose. With the ultrahigh magnetic field of 9.4 T, a 2H array RF coil and a fast Ernst angle acquisition, we were able to acquire temporally resolved DMI acquisitions with a temporal resolution of 10 min and a nominal voxel size of 2.97 ml, which opens the potential for the investigation of the glycolytic flux at the human brain with DMI.

4.1. RF coil design

To be able to achieve this, a dedicated dual tune 2H/1H transceiver array coil design (10 TxRx channels for proton and 8TxRx/2Rx channels for deuterium) for whole brain coverage and optimized SNR was presented. In former publications, a 2H four-coil element transceiver phased array (De Feyter et al., 2018), surface coils (de Graaf et al., 2020) and a birdcage coil (Gursan et al., 2020) were used for DMI of the human brain. Phased array transceiver coils combine the advantages of volume birdcage coils with respect to efficiency and homogeneity of the RF transmission and surface coils on the reception side as they allow for whole brain coverage with increase in SNR close to the loop elements. In case of a high density receive array, the inhomogeneous reception B1 field can be challenging for quantification of metabolite amplitudes and usually needs correction and the high peripheral SNR may amplify unwanted signal from the skull. Therefore, a coil design with a relatively low number of larger receive elements was chosen. With this design, the gradient between periphery and center is rather benign while the peripheral SNR gain due to a phased array design is preserved.

4.2. Alternative methods and tracers

The availability of 2H RF coils is still very limited. If only a 1H coil is available, an interesting alternative approach to investigate the glucose metabolism was presented by Rich et al. (Rich et al., 2020) called quantitative exchanged-labeled turnover MRS (qMRS). In this method, the labeled 2H glucose is indirectly detected via 1H MRS. Because of the replacement of 1H by 2H, a signal reduction can be detected for the corresponding 1H detectable metabolites which enables an indirect detection of the 2H tracer uptake. A systematic comparison between DMI and qMRS concerning the sensitivity of the detection of the different labeled metabolites is still missing and should be addressed in future research studies.

Other methods, which are able to detect the glycolytic flux, as FDG-PET and 13C MRS(I) were already mentioned in the introduction. FDG-PET has the major disadvantage of the radioactive radiation exposure due to the radioactive tracer. The experimental sensitivity of non-hyperpolarized 13C MRSI and DMI were compared in a recent publication by de Graaf et al. (de Graaf et al., 2020), showing a higher sensitivity for DMI.

Beside these alternative methods, other 2H-labeled tracers could be considered as labeled acetate (Li et al., 2019), choline (HM De Feyter et al., 2021) or [2,3–2H2]-fumarate (Hesse et al., 2021). To investigate the metabolic flux of glucose, [2H7]-glucose could be applied as a tracer. The major advantage would be a higher overall 2H signal amplitude due to a higher number of 2H-labeled chemical groups. Unfortunately, this also increases the complexity of the detected MR spectrum (De Feyter et al., 2018).

4.3. T1 relaxation times

The measured relaxation times presented in this study are slightly higher than the times which were measured at 4 T (human brain) and 11.7 T (rat brain) (De Feyter et al., 2018). Overall, longitudinal relaxation times of deuterated water seem to be very stable over a range of different magnetic fields B0 (De Feyter et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2017; Assaf et al., 1997; Bogin et al., 2002; Brereton et al., 1986; Eng et al., 1990; Evelhoch et al., 1989; Hwang et al., 1991; Irving et al., 1987). The relatively low relaxation times of deuterated water can be explained by the quadrupole momentum of the 2H nucleus. This enables short repetition times, which improves the sensitivity of the 2H MR measurements.

For sequence optimization, the T1 relaxation times of deuterated glucose and Glx would be of interest as well. Due to the low natural abundance, these T1 relaxation times could be measured only after the administration of deuterated glucose. As the concentration of the labeled glucose and Glx is constantly changing after the oral intake of deuterated glucose (as presented in this publication), the measurement of related T1 relaxation times is prone to errors. Approximate values are given in De Feyter et al. for 4 T1. Similar to deuterated water, it can be expected that the relaxation times of the metabolites do not differ significantly between different magnetic field strengths.

4.4. Imaging of dynamic 2H uptake

4.4.1. 2H MRSI methodology

With the presented RF coil design and the measured T1 relaxation times, we were able to optimize a fast short TE and TR k-space weighted Ernst angle 2H 3D MRSI sequence with temporal resolution of 10 min and whole-brain coverage. The resulting metabolite images show interesting correspondences of energy metabolism reflected by DMI to the anatomical distribution of GM and WM tissue as well as CSF.

In future studies, the temporal and/or spatial resolution could be further improved by using acceleration techniques. Promising are methods that exploit the sparsity of the 2H spectra due to the limited number of metabolite resonance lines, e.g. SPICE (Lam et al., 2016), compressed sensing (Lustig et al., 2007; Larson et al., 2011) or interleaved imaging techniques, e.g. bSSFP (Speck et al., 2002; Leupold et al., 2009) or IDEAL. For all these methods, the limited SNR of the 2H MR measurement should be considered and is certainly the major limiting factor. Therefore, implementations of accelerated imaging methods for human brain imaging at ultrahigh field in combination with denoising techniques such as low rank reconstruction approaches (Lam et al., 2016), Tucker decomposition (Kreis et al., 2020) or SPICE (Li et al., 2021) would be especially of interest.

4.4.2. Brain tissue type specific analysis

As proof-of-principle, an analysis of metabolic uptake in different brain tissue types was performed (Fig. 8/9). It could be shown that the uptake of deuterated glucose and label incorporation into its downstream metabolites water and Glx is higher in GM rich tissue compared to WM rich tissue. This is consistent with previous measurements that utilized 13C-labeled glucose. It is known from these measurements that the tricarboxylic acid cycle rate is higher in gray matter compared to white matter (Mason et al., 1999; de Graaf et al., 2001), which is further supported by our 2H MRSI results.

The analysis presented in Fig. 10 indicates that a small increase of lactate is detectable in the healthy human brain using averaged 2H MRSI voxel. For 2H MRSI voxel with high skull tissue fraction, this ppm-range is most likely dominated by lipid resonances. Corresponding analysis revealed that these resonances do not change strongly after the oral administration of 2H-labeled glucose. The small increase in skull rich tissue probably arises from lactate contributions from included brain tissue. The overlapping of these resonances need to be considered for the interpretation of 2H MRSI data.

Conclusion

This work presents the first DMI measurements of the healthy human brain at a magnetic field strength of B0 = 9.4 T after the oral administration of [6,6′−2H2]-labeled glucose. We were able to present an improved spatial resolution compared to earlier publications at lower field as well as first temporal resolved metabolite images of deuterated water, glucose and Glx at the human brain with a time resolution of 10 min. Brain tissue type specific 2H uptakes were investigated and proved to be consistent with expected differences in oxidative metabolism between GM and WM . It could be shown that DMI is a robust method to detect glucose as well as Glx enrichment after the oral consumption of deuterated glucose. The lactate resonance is small in healthy tissue and potential contaminations from lipid tissue should be considered.

Credit author statement

Loreen Ruhm: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Project administration, Writing - Original Draft Nikolai Avdievich: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing Theresia Ziegs: Investigation Armin M. Nagel: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing Henk M. De Feyter: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing Robin A. de Graaf: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing Anke Henning: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing

Data and code availability statement

Anonymized data as well as the source code for the applied data evaluation will be provided upon request for non-commercial research use under a data transfer agreement between the Max Planck Society, who acts as a representative, and the receiving party.

Acknowledgements

Funding by the ERC Starting Grant (SYNAPLAST MR, Grant No. 679927) of the European Union and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT, Grant No. RR180056) is gratefully acknowledged. This study is supported in part by NIH Grant R01 EB025840.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118639.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Albers M.J., Bok R., Chen A.P., et al. Hyperpolarized 13C lactate, pyruvate, and alanine: noninvasive biomarkers for prostate cancer detection and grading. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8607–8615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S.P., Morrell G.R., Peterson B., et al. Phase-sensitive sodium B1 mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011;65(4):1125–1130. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf Y., Navon G., Cohen Y. In vivo observation of anisotropic motion of brain water using 2H double quantum filtered NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 1997;37(2):197–203. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avdievich N.I., Ruhm L., Dorst J., et al. Double-tuned 31P/1H human head array with high performance at both frequencies for spectroscopic imaging at 9.4T. Magn. Reson. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;84(2):1076–1089. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogin L., Margalit R., Ristau H., et al. Parametric imaging of tumor perfusion with deuterium magnetic resonance imaging. Microvasc. Res. 2002;64(1):104–115. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2002.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brereton I.M., Irving M.G., Field J., et al. Preliminary studies on the potential of in vivo deuterium NMR spectroscopy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986;137(1):579–584. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(86)91250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bydder M., Hamilton G., Yokoo T., et al. Optimal phase array combination of spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2008;26(6):847–850. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wei Z., Chan K.W., et al. D-Glucose uptake and clearance in the tauopathy Alzheimer's disease mouse brain detected by on-resonance variable delay multiple pulse MRI. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(5):1013–1025. doi: 10.1177/0271678x20941264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feyter H.M., de Graaf R.A. Deuterium metabolic imaging – back to the future. J. Magn. Reson. 2021;326 doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2021.106932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feyter H.M., Behar K.L., Corbin Z.A., et al. Deuterium metabolic imaging (DMI) for MRI-based 3D mapping of metabolism in vivo. Sci. Adv. 2018;4(8):eaat7314. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feyter H.M., Thomas M.A., Behar K.L., et al. NMR visibility of deuterium-labeled liver glycogen in vivo. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86(1):62–68. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feyter H.M., Monique T., Ip K., et al. Proceeding of the 2021 ISMRM & SMRT Virtual Conference & Exhibition. 2021. Delayed mapping of 2H-labeled choline using deuterium metabolic imaging (DMI) reveals active choline metabolism in rat glioblastoma. Virtual Meeting:0016. [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R.A., Pan J.W., Telang F., et al. Differentiation of glucose transport in human brain gray and white matter. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21(5):483–492. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R.A., Hendriks A.D., Klomp D.W.J., et al. On the magnetic field dependence of deuterium metabolic imaging. NMR Biomed. 2020;33(3):e4235. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R.A., Thomas M.A., Behar K.L., et al. Characterization of kinetic isotope effects and label loss in deuterium-based isotopic labeling studies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021;12(1):234–243. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf R.A. WILEY; 2008. Vivo NMR Spectroscopy - Principles and Techniques. Second Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Eng J., Berkowitzt B.A., Balaban R.S. Renal distribution and metabolism of [2H9]choline. A 2H NMR and MRI study. NMR Biomed. 1990;3(4):173–177. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940030405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelhoch J.L., McCoy C.L., Giri B.P. A method for direct in vivo measurement of drug concentrations from a single 2H NMR spectrum. Magn. Reson. Med. 1989;9(3):402–410. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910090313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H., Matsuzawa T., Abe Y., et al. Experimental study for cancer diagnosis with positron-labeled fluorinated glucose analogs: [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-mannose: a new tracer for cancer detection. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1982;7:294–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00253423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursan A., Hendriks A.D., van Genderen S.R., et al. Proceeding of the 2020 ISMRM & SMRT Virtual Conference & Exhibition. 2020. Development of a 2H birdcage volume coil for homogeneous deuterium metabolic imaging of the human brain at 7T. [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg G., Bause J., Ethofer T., et al. Whole brain MP2RAGE-based mapping of the longitudinal relaxationtime at 9.4T. Neuroimage. 2017;144:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann B., Müller M., Seyler L., et al. Feasibility of deuterium magnetic resonance spectroscopy of 3-O-Methylglucose at 7 Tesla. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse F., Somai V., Kreis F., et al. Monitoring tumor cell death in murine tumor models using deuterium magnetic resonance spectroscopy and spectroscopic imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021;118(12) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014631118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y.C., Kim S.-.G., Evelhoch J.L., et al. Modulation of murine radiation-induced fibrosarcoma-1 tumor metabolism and blood flow <em>in situ</em>via glucose and mannitol administration monitored by 31P and 2H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Cancer Res. 1991;51(12):3108–3118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving M.G., Brereton I.M., Field J., et al. In vivo determination of body iron stores by natural-abundance deuterium magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 1987;4(1):88–92. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910040111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreis F., Wright A.J., Hesse F., et al. Measuring tumor glycolytic flux in vivo by using fast deuterium MRI. RadiologyRadiology. 2020;294(2):289–296. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019191242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd M.E., Bachert P., Meyerspeer M., et al. Pros and cons of ultra-high-field MRI/MRS for human application. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2018;109:1–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam F., Ma C., Clifford B., et al. High-resolution 1H-MRSI of the brain using SPICE: data acquisition and image reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016;76(4):1059–1070. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson P.E.Z., Hu S., Lustig M., et al. Fast dynamic 3D MR spectroscopic imaging with compressed sensing and multiband excitation pulses for hyperpolarized 13C studies. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011;65(3):610–619. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leupold J., Månsson S., Stefan Petersson J., et al. Fast multiecho balanced SSFP metabolite mapping of 1H and hyperpolarized 13C compounds. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys., Biol. Med. 2009;22(4):251–256. doi: 10.1007/s10334-009-0169-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhu X.-.H., Zhu W., et al. Dynamic deuterium mrs imaging for studying rat heart energy metabolism in vivo – initial experience. Proceeding of the 2019 ISMRM & SMRT Annual Meeting & Exhibition; Montreal, Canada; 2019. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhao Y., Guo R., et al. Machine learning-enabled high-resolution dynamic deuterium MR spectroscopic imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2021:1. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2021.3101149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Zhu X.-.H., Zhang Y., et al. In vivo application of 3D deuterium (2H) CSI for quantitative imaging of cerebral glucose metabolism at ultrahigh field. Proceeding of the 2015 ISMRM & SMRT Annual Meeting & Exhibition; Toronto, Canada; 2015. p. 4719. [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Zhu X.-.H., Zhang Y., et al. Simultaneous assessment of abnormal glycolysis and oxidative metabolisms in brain tumor using in vivo deuterium MRS Imaging. Proceeding of the 2016 ISMRM & SMRT Annual Meeting & Exhibition; Singapore; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Zhu X.-.H., Zhang Y., et al. Quantitative assessment of brain glucose metabolic rates using in vivo deuterium magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(11):3518–3530. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17706444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig M., Donoho D., Pauly J.M. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn. Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1182–1195. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason G.F., Pan J.W., Chu W.-.J., et al. Measurement of the tricarboxylic acid cycle rate in human grey and white matter in vivo by 1H- [13C] magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 4.1T. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19(11):1179–1188. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkes C., Shajan G., Chadzynski G., et al. 31)P CSI of the human brain in healthy subjects and tumor patients at 9.4 T with a three-layered multi-nuclear coil: initial results. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys., Biology and Medicine. 2016;29(3):579–589. doi: 10.1007/s10334-016-0524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S.J., Kurhanewicz J., Vigneron D.B., et al. Metabolic imaging of patients with prostate cancer using hyperpolarized [1-13C] pyruvate. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5(198):198ra108. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordidge R.J., Wylezinska M., Hugg J.W., et al. Frequency offset corrected inversion (FOCI) pulses for use in localized spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 1996;36:562–566. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny W., Friston K., Ashburner J., et al. 1st Edition. Academic Press; 2006. Statistical Parameter Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images. [Google Scholar]

- Pohmann R., Raju S., Scheffler K. T1 values pf phosphorus metabolites in the human visual cortex at 9.4 T. Proceeding of the ISMRM Annual Meeting 2018; Paris, France; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rich L.J., Bagga P., Wilson N.E., et al. 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy of 2H-to-1H exchange quantifies the dynamics of cellular metabolism in vivo. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:335–342. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0499-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riis-Vestergaard M.J., Laustsen C., Mariager C.Ø., et al. Glucose metabolism in brown adipose tissue determined by deuterium metabolic imaging in rats. Int. J. Obes. 2020;44(6):1417–1427. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers C.T., Robson M.D. Receive array magnetic resonance spectroscopy: whitened singular value decomposition (WSVD) gives optimal Bayesian solution. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010;63(4):881–891. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck O., Scheffler K., Hennig J. Fast 31P chemical shift imaging using SSFP methods. Magn. Reson. Med. 2002;48(4):633–639. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhamme L., van den Boogaart A., Van Huffel S. Improved method for accurate and efficient quantification of MRS data with use of prior knowledge. J. Magn. Reson. 1997;129:35–43. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.-.H., Chen W. In vivo X-nuclear MRS imaging methods for quantitative assessment of neuroenergetic biomarkers in studying brain function and aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018;10(394) doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data as well as the source code for the applied data evaluation will be provided upon request for non-commercial research use under a data transfer agreement between the Max Planck Society, who acts as a representative, and the receiving party.