Abstract

Existing evidence suggests that children from around the age of 8 years strategically alter their public image in accordance with known values and preferences of peers, through the self-descriptive information they convey. However, an important but neglected aspect of this ‘self-presentation’ is the medium through which such information is communicated: the voice itself. The present study explored peer audience effects on children's vocal productions. Fifty-six children (26 females, aged 8–10 years) were presented with vignettes where a fictional child, matched to the participant's age and sex, is trying to make friends with a group of same-sex peers with stereotypically masculine or feminine interests (rugby and ballet, respectively). Participants were asked to impersonate the child in that situation and, as the child, to read out loud masculine, feminine and gender-neutral self-descriptive statements to these hypothetical audiences. They also had to decide which of those self-descriptive statements would be most helpful for making friends. In line with previous research, boys and girls preferentially selected masculine or feminine self-descriptive statements depending on the audience interests. Crucially, acoustic analyses of fundamental frequency and formant frequency spacing revealed that children also spontaneously altered their vocal productions: they feminized their voices when speaking to members of the ballet club, while they masculinized their voices when speaking to members of the rugby club. Both sexes also feminized their voices when uttering feminine sentences, compared to when uttering masculine and gender-neutral sentences. Implications for the hitherto neglected role of acoustic qualities of children's vocal behaviour in peer interactions are discussed.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Voice modulation: from origin and mechanism to social impact (Part II)’.

Keywords: acoustics, voice gender, voice pitch, vocal tract resonances, vocal masculinity, audience effects

1. Introduction

Children's peer relationships have received considerable attention over the past 30 years as a key socialization context for children's gendered behaviour. By 3 years of age, children spontaneously segregate into same-sex peer groups [1] and continue to do so throughout the school years [2]. As children value their ingroup membership, they become increasingly concerned about peer group norms on gender [3–5], and the negative consequences associated with not complying with them such as being teased, shunned or referred to as ‘tomboys’ or ‘sissies’ [6,7]. For example, toddlers play less with counter-stereotypical toys in the presence of peers than when alone [8]. Primary school children are also more likely to show a preference for own-sex-typed toys and activities when peers are present than when alone, particularly young boys who hold the most rigid stereotypes [9]. Building on such evidence that children display or inhibit particular behaviours in line with external or internal rules and standards (e.g. [10,11]) researchers have shown that children increasingly engage in diverse forms of self-presentational behaviour—behaviour specifically intended to control others' impressions of the self—in accordance with known values and preferences of peers. For instance, using self-presentational stories involving emotion-masking displays, Banerjee & Yuill [12] have shown children as young as six years assign to protagonists facial expressions which are incongruent with their real emotions if the latter were likely to attract negative evaluations by the story audience (e.g. the protagonist being judged as stupid, a cry-baby or greedy).

By the end of primary school self-presentation motives become increasingly salient and children increasingly adapt self-presentation strategies to specific goals. For instance, in a study of 6- to 10-year olds, Aloise-Young [13] found that older children (especially from age 8 years onwards) spontaneously tailored their self-descriptions in order to promote themselves to and ingratiate themselves with a peer audience (specifically to convince other children to pick them as a partner for a game). Similarly, in a series of three experiments with the same age range, Banerjee [14] reported that even children in the youngest age group (age 6–7 years) were able to acknowledge the evaluative preferences of a given audience and to alter their choices of self-descriptive options to match those preferences, and that the tendency to do so increased with age.

However, while this literature demonstrates children's ability to engage in verbal self-presentation, we know little about children's self-presentational control of the medium through which such verbal information is communicated: the voice itself. Interestingly, converging evidence from acoustic [15,16] and anatomical [17] studies indicates that differences between pre-pubertal boys' and girls’ voices are largely behavioural. Consistent with the absence of appreciable sex differences in the vocal apparatus before puberty, boys and girls speak with a similar mean fundamental frequency (F0, the correlate of voice pitch). However, boys speak with lower formants (the resonances produced by the vocal tract) and narrower formant spacing (ΔF, the distance among adjacent formants) than girls, giving them a deeper, more masculine voice. Boys and girls with more masculine voices (lower ΔF) are also rated, by both child and adult listeners, as having more stereotypical masculine profiles (e.g. in preferences for toys, playmates, activities) than children with less masculine voices [18]. As well as variation in sex-related voice cues affecting listeners' perception of children's masculinity and femininity, children appear to volitionally manipulate F0 and ΔF when giving voice to stereotypically masculine or feminine child characters of the same age and sex as themselves [19].

Integrating these findings, it is theoretically plausible that children's self-presentational motivations will extend to their ability to masculinize and feminize their voices in accordance with gender-stereotyped perceptions of peer audiences. The present study tests this hypothesis by investigating whether children vary their F0 and ΔF when impersonating a child of the same age and sex as themselves who is trying to ingratiate themself with a group of same-sex peers engaging in stereotypically masculine or feminine interests (e.g. rugby players versus ballet dancers). This ‘making friends’ scenario is often used in the peer relations literature (e.g. [20–22]) as this type of situation is common in children's (and adults’) social interactions and can prime behavioural appropriateness according to social norms and expectations [14,23]. Specifically, the present study examined hypothetical interactions with same-sex peers, given that preferences for same-sex friends dominate social interactions and friendships throughout childhood [2].

We hypothesized that (H1) children would feminize their voice (by raising F0 and increasing ΔF) when imagining they were addressing the ballet club and masculinize their voice (by lowering F0 and narrowing ΔF) when addressing the rugby club. In line with previous research, we also expected (H2) children to preferentially select stereotypically masculine or feminine self-descriptive statements when playing the role of a child character who is seeking to ingratiate themselves with peers known to have masculine or feminine interests (rugby or ballet). Given that previous research has found that children with the most rigid stereotypes are more likely to present themselves as sex-typed in front of a peer audience [9], we also expected that (H3) children who stereotype more strongly in terms of choice of statements would also exhibit greater voice variation between the two audiences.

The present study included children aged 8–10 years old to ensure that the participants had the literacy skills needed for completing the tasks. This age group also allowed us to test our hypotheses before the onset of pubertal changes to the vocal apparatus [24]. Moreover, previous research has shown that from around 8 years of age, children exhibit verbal self-presentation in response to audience characteristics [13,14,25]. It is also from about this age that children rely on gender individuating information from multiple dimensions (e.g. physical appearance and interests), as well as gender labelling, when making social judgements [26].

2. Methods

(a) . Participants

Participants were 56 children (30 males, 26 females) recruited from UK school years 4 and 5, aged 8–10 years (mean age = 8.7, s.d. = 0.84) in three local primary schools (one from a city and two from two small towns). Children represented different socioeconomic status (SES) groups (proportion eligible for free school meals: 2.2%, 14.8% and 33.3%) and were mostly of white ethnicity (96.5%, 87% and 74.1% children). Children were recruited through an advertisement in the school newsletters. School leaders provided informed consent, and parents were additionally provided with information letters and an opportunity to withdraw their children from participation (less than 30% did so in any school). All children were native English speakers and had no history of speech or hearing impairments. Children were tested individually on the school premises. The procedure was granted ethics approval by the Sciences & Technology Cross-Schools Research Ethics Committee (C-REC) at the University of Sussex (certificate: ER/VC44/8).

(b) . Procedure

Participants sat in a comfortable chair and were audio recorded with a Zoom H1 handheld recorder, which was positioned at approximately 30 cm from the participant, with a Marantz shield around it. Next, children were presented with two short vignettes via a PowerPoint presentation with pre-recorded narration. Each vignette involved a fictional protagonist of the same age and sex as the participants (electronic supplementary material, Appendix S1). Participants were told to imagine that this child had joined a new school, and on their first day, he or she had met with some new peers of the same age and sex as themselves. These peers belonged to either a rugby club (peer audience engaging in a stereotypically masculine activity) or a ballet club (peer audience engaging in stereotypically feminine activity). Children were told in each story that the protagonist wanted to make friends with the given peer audience. They were presented with a set of three self-descriptive statements (masculine, feminine or neutral), chosen pseudo-randomly from a set of 12 (electronic supplementary material, Appendix S2). Children were then asked to read out all three statements in the order presented as if they were the character speaking to that audience and as if they were true of the child character. Next, children were asked to select the statement which in their opinion the protagonist should say to the peer audience in order to be liked by them. This procedure was repeated twice more for each audience, with a new set of three (masculine, feminine and neutral) sentences each time. Therefore, each child read out nine self-descriptive statements (three stereotypically masculine, three stereotypically feminine and three neutral) as a child character speaking to the ballet club, and nine as a child character speaking to the rugby club. The choice of statements, the order of the statements within each set and the order of the two imagined audiences (ballet club, rugby club) were counterbalanced across groups of children. The vignettes and questions were presented in PowerPoint on a MacBook Air, placed behind, but above the recorder, so that the screen was in full view.

(c) . Acoustic analyses

For each sentence spoken by the child, we extracted the mean fundamental frequency (F0) and the centre frequencies of the first four formants (F1–F4) using a custom batch-processing script (see the electronic supplementary material, S1) that was written using PRAAT software [27]. For each recording, the script overlaid the computed F0 and formant values on narrowband spectrograms, which allowed the researcher to manually correct for erroneous estimates (values departing from visually estimated fundamental and formant frequencies). The parameters for F0 were set as follows: pitch floor 100 Hz, pitch ceiling 450 Hz and time step 0.01 s. The parameters for formant analysis were set as follows: number of formants 6, max formant 8000 and dynamic range 30 dB. Given that the frequency of each individual formant is related to formant spacing (ΔF) by equation (2.1):

| 2.1 |

We derived ΔF by plotting mean formant frequencies for sentence against the expected increments of formant spacing [(2i−1)/2], where ΔF is equal to the slope of the linear regression line with an intercept set to 0, as in [28]. This acoustic analysis procedure has been applied successfully in previous studies to estimate ΔF from children's speech (e.g. [18,29]).

(d) . Statistical analyses

Linear mixed models (LMMs) fitted using maximum-likelihood estimation were used to examine the main and interaction effects of speaker sex (between participants), audience (ballet club, rugby club) and sentence type (masculine, neutral, feminine) and order presentation of the sets (1, 2 or 3) (within participants), on each acoustic parameter (F0 and ΔF) separately (H1). Sentence number within sentence type (allowing the intercept to vary between sentences) and participant identity (allowing the intercept to vary between participants) were included as random factors. The main effects of within-participant factors audience, sentence type and set number were included as random slopes. For all LMMs, we checked the residuals for normality with a quantile-quantile plot and histogram (electronic supplementary material, S2), and there was no indication of this assumption being violated.

In order to establish whether children preferentially selected gender-stereotypical statements when speaking to the ballet or rugby club (H2), we first coded the choice of sentence in each set as 1 or 0. These codes represented, respectively, whether children chose self-descriptive statements in accordance with the stereotyped interests of the peer audience, or not (i.e. participants scored 1 if the feminine/masculine sentence was chosen when speaking to the ballet/rugby club, and 0 otherwise). We then ran a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) on the stereotype-matching sentence choice (0 or 1) with speaker sex, audience, set number and their interactions as fixed factors, sentence number within sentence type, and participant identity as a random factor. For the LMM and GLMM, pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were used for fixed factors with more than two levels. Confidence intervals on the means for the Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons were determined by bootstrap resampling 1000 times [30]. LMMs and GLMMs were run in RStudio (analysis script as electronic supplementary material, S3 and S4) [31].

Finally, we investigated whether frequency shifts in F0 and ΔF between the two audience groups were significantly associated with the choice of sentences that would most ingratiate them to the given audience (H3), using SPSS v.24 [32]. For each speaker, we first calculated the average difference in F0 and ΔF between the sentences spoken to the ballet and rugby clubs, by averaging, respectively, F0 and ΔF across all sentences addressed to the ballet club and subtracting the averaged F0 and ΔF across all sentences addressed to the rugby club. We then correlated, for boys and girls separately, the F0 and ΔF difference scores with the average number of stereotype-matching sentence choices made for each audience (i.e. masculine self-descriptions for the rugby club; feminine self-descriptions for the ballet club), and also with the average total number of stereotyping-matching choices across the two audiences.

3. Results

(a) . Audience effects on voice manipulations (H1)

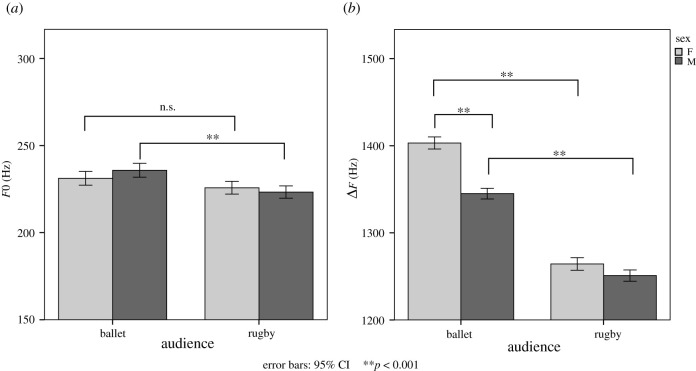

The results of our LMMs are reported in table 1. There was a significant main effect of audience on children's F0 and ΔF. Simultaneous pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni correction indicated that the children spoke with a significantly higher mean F0 when addressing the imagined same-sex feminine (ballet) audience (M = 233 Hz, 95% confidence interval (CI) [227, 240]), compared to when addressing the imagined same-sex masculine (rugby) audience (M = 225 Hz, 95% CI [219, 231]), p < 0.001. They also spoke with a significantly higher ΔF when addressing the feminine audience (M = 1374 Hz, 95% CI [1363,1386]), compared to when addressing the masculine audience (M = 1259 Hz, 95% CI [1247,1270]). As expected, the LLM also confirmed a significant main effect of sex on ΔF, as on average boys spoke with lower ΔF (M = 1296 Hz, 95% CI [1283,1308]) than girls (M = 1337, 95% CI [1323,1350]) across both conditions.

Table 1.

LMMs testing the effects of the experimental factors on F0 and ΔF.

| d.f. 1 | d.f. 2 | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | ||||

| sex | 1 | 53.57 | 0.34 | 0.561 |

| audience type | 1 | 53.89 | 17.89 | <0.001 |

| sentence type | 2 | 47.36 | 3.76 | 0.030 |

| set number | 2 | 53.37 | 6.41 | 0.003 |

| sex by audience type | 1 | 52.91 | 5.19 | 0.026 |

| audience type by sentence type | 2 | 634.26 | 3.60 | 0.027 |

| ΔF | ||||

| sex | 1 | 53.91 | 26.07 | <0.001 |

| audience type | 1 | 54.37 | 392.13 | <0.001 |

| sentence type | 2 | 17.65 | 5.31 | 0.0156 |

| set number | 2 | 56.76 | 0.29 | 0.747 |

| sex by audience type | 1 | 54.02 | 11.53 | 0.001 |

| audience type by sentence type | 2 | 720.35 | 6.93 | 0.001 |

| sex by set number | 2 | 67.6 | 5.87 | 0.004 |

There was a significant interaction effect of sex and audience type on both F0 and ΔF (figure 1). Both boys and girls raised their F0 when addressing the feminine audience (girls: M = 230 Hz, 95% CI [220,238]; boys: M = 237 Hz, 95% CI [228,245]) relative to the masculine audience (girls: M = 227 Hz, 95% CI [217,234]; boys: M = 225 Hz, 95% CI [217,233]), but this shift was significant in boys only, p < 0.001. Additionally, while both boys and girls raised their ΔF when addressing the feminine audience relative to the masculine audience, this shift was larger in girls than in boys, p < 0.001. There was a significant main effect of sentence type on children's F0 and ΔF. Stereotypically feminine self-descriptions were spoken with a significantly higher F0 (M = 234 Hz, 95% CI [227,240]) and higher ΔF (M = 1327 Hz, 95% CI [1315,1342]) than the neutral sentences (F0: M = 227 Hz, 95% CI [221,233]; ΔF: M = 1301 Hz, 95% CI [1289,1316]), p < .05, and a non-significant trend was also observed in comparison with the masculine sentences (F0: M = 227 Hz, 95% CI [219,235]); ΔF:M = 1319 Hz, 95% CI [1307,1331]), ps < 0.15. Additionally, there was a significant interaction effect of sentence type with audience type on F0 and ΔF, in that the difference between feminine sentences and the other two sentence types was larger when addressing the feminine audience relative to the masculine audience, while both boys and girls uttered the gender-neutral sentences with a significantly lower ΔF compared to the masculine sentences, p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Girls' and boys’ F0 (Hz) (a), and ΔF (b) when addressing the ballet and rugby clubs.

There was a significant main effect of set number on children's F0: F0 decreased overall with the sets and was significantly lower in the last set (M = 226 Hz, 95% CI [220, 232]), compared to the first (M = 231 Hz, 95% [225, 238]), p = 0.006. Additionally, there was a significant interaction effect of sex and set number on children's ΔF. Boys’ ΔF was significantly lower in the last set (M = 1291 Hz, 95% CI [1277, 1305]), compared to the first (M = 1300 Hz, 95% CI [1287,1313]), p = 0.04, while girls' ΔF did not significantly change with set number.

(b) . Sentence choice (H2)

As expected, the GLMM revealed that all children preferentially selected stereotypically feminine sentences (boys: M = 0.70, 95% CI [0.65, 0.76]; girls: M = 0.67, 95% CI [0.62, 0.74]) when speaking to the ballet audience, and stereotypically masculine sentences when speaking to the rugby (boys: M = 0.75, 95% CI [0.69, 0.80]; girls: M = 0.69, 95% CI [0.62, 0.75]), with no significant difference being found in the degree of stereotyping for the two audiences, p > 0.05. Moreover, stereotypical choices by boys and girls in both conditions (calculated by taking the mean score across the three sets in each audience condition) were consistently significantly above chance (one-tailed t-tests ps < 0.001, comparing against a chance value of 0.33).

(c) . Is there a relationship between sentence choice and degree of voice adjustments? (H3)

Correlations of the F0 and ΔF differences between the two audience conditions with the average number of stereotype-matching sentence choices made for each condition (i.e. masculine self-descriptions for the rugby audience; feminine self-descriptions for the ballet audience), and with the total number of stereotype-matching choices across both stories together, were non-significant, rs between −0.31 and 0.07, all ps > 0.10. Thus, differentiating between audiences in terms of spontaneous changes to vocal pitch and resonance was not associated with explicit choices of stereotyped self-descriptions to match audience characteristics (electronic supplementary material, table S1 in Appendix S3).

4. Discussion

In line with our hypotheses, this study reveals that the presence of an imagined same-sex peer audience with masculine or feminine interests affects children's self-presentations. Effects emerged not just in their choice of self-descriptive statements but also in the modulation of vocal characteristics associated with masculinity and femininity. More specifically, when impersonating a fictional child trying to make friends with same-sex peers engaging in a stereotypically feminine activity (ballet club), children overall systematically feminized their voices (by raising their F0 and ΔF). However, they masculinized their voices (by lowering their F0 and ΔF) when speaking to same-sex peers engaging in a stereotypically masculine activity (rugby club).

The role of non-verbal vocal behaviour in children's self-presentation has hitherto been unexplored. However, our results add to a long-established line of research showing that children's non-verbal displays in other dimensions often accompany verbal strategies for producing desired self-presentational outcomes. These include the strategic use of crying in help-seeking scenarios [33], the use of smiling in conflict situations [34,35] and ‘looking down one's nose’ where children try to convey an impression of competence [36] as well as the deliberate suppression of expressions of anger or hurt feelings in response to provocation [37].

Our results are also consistent with the view that children's gender schemas—the networks of cognitive associations that organize and guide perceptions and understanding of the world on the basis of gender (see [38])—include correspondences between sexually dimorphic voice cues (lower ΔF in pre-pubertal boys than girls, and lower F0 and ΔF in men than women) and gender-related characteristics (lower frequencies being associated with greater masculinity). Previous voice production studies have shown that children's gender schemas include a vocal component. Children manipulate fundamental and formant frequency values towards those expected from the sex dimorphism in adult voices when asked to sound like a boy or a girl [29], when giving voice to peers with masculine or feminine interests [19], and when asked to impersonate adults in stereotypically masculine and feminine occupations [39]. Our study extends previous findings by showing that children are not only capable of manipulating their voice masculinity and femininity in response to an explicit request, but that they also spontaneously modulate them in a stereotypical way in the presence of peers, in line with the audience's masculine or feminine interests.

(a) . Verbal versus non-verbal displays of self-presentation

In line with previous studies [9,12–14], we also found that when children were trying to ingratiate themselves with their audience, they selected statements that matched the peers' choice of gender-typed activity. They preferentially selected stereotypically masculine self-descriptions when addressing the rugby club, and stereotypically feminine self-descriptions when addressing the ballet club. However, we did not find a relationship between the extent of voice manipulations and how strongly children were inclined to choose stereotypical statements. Although Banerjee & Lintern [9] previously reported higher levels of sex-typed self-descriptive statements in children with more rigid gender stereotypes, this kind of explicit choice of verbal self-description may be independent of the spontaneous stereotype processes manifested in children's vocal productions. In support of this explanation, several studies have reported only a weak relationship between implicit and explicit measures of gender stereotyping (e.g. [39–41]).

We also observed an interaction between non-verbal vocal strategies and the content of the sentences spoken by children. Children feminized their voices when uttering the feminine sentences, by raising both F0 and ΔF compared to the other two sentence types, while they did not masculinize their voices when uttering the masculine sentences. Psychoacoustic studies with adult listeners have shown that compared to lower frequency voices, higher vocal frequency voices evoke an attribution of greater friendliness and cooperativeness [42,43], which would be a valued attribute in our hypothetical scenario of making friends. Thus, the strategy of lowering one's voice to express masculinity may have been constrained by the risk of sounding unfriendly. On the other hand, raising one's voice to express femininity may have converged with children's desire to signal friendliness.

(b) . Sex differences in non-verbal vocal self-presentation

While our analyses revealed that both sexes shifted the sex-related cues of their voice in line with adult sex dimorphism, the role of F0 and ΔF in the expression of masculinity and femininity appears to vary between the two sexes. This pattern of results is likely to be driven by sex-specific differences in articulatory behaviour, given the absence of overall differences in the vocal apparatus between the two sexes prior to puberty. Specifically, we found that girls' ΔF was 60 Hz higher than boys’ when addressing the feminine audience. It is possible that girls spread their lips more than boys when addressing the feminine audience, which would cause a shortening of the vocal tract and therefore a wider ΔF [44]. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis [45] reveals that women smile (thus spreading their lips) more than men, particularly when gender-appropriate norms are emphasized, and this difference appears to be already present by the age of 9 years [46]. In terms of F0, boys differentiated between audiences more than girls did, with boys speaking with a 7 Hz higher and 2 Hz lower F0 than girls when speaking to the feminine and masculine audience, respectively. While the difference in girls' F0 between the two audiences was in the expected direction, it was not statistically significant. This suggests that boys increased/decreased the rate of vocal fold vibration to a greater extent than girls, resulting in the observed higher/lower mean F0 when addressing the feminine and masculine audience, respectively. Although small, these differences are in line with a previous study showing that boys manipulate their F0 to a greater extent than their ΔF when giving voice to a boy with feminine versus a boy with masculine interests [19].

(c) . Limitations and future research

A number of suggestions for future research emerge from the findings of the present study. First, we reported a slight decrease in F0 (both sexes) and ΔF (boys only) with number of task repetitions (sets). This result was also found in a study with children of this age group [47] and may be at least partly influenced by laryngeal fatigue and practice effects [48]. A further methodological refinement would therefore be to assess the optimal number of trials required to reach representative speaking F0 values. Second, our study included a relatively small and mainly white sample from a relatively narrow SES range. Cross-cultural comparisons using larger samples should establish the extent to which our findings can be generalized to diverse cultural contexts, outside that of western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic (WEIRD) societies [49].

Third, our paradigm could be implemented with children spanning a wider age range, as developmental changes in vocal self-presentational behaviour are likely to reflect the combined development of social experience (e.g. amount of peer interaction), cognitive processes (e.g. perspective-taking abilities), gender stereotyping, as well as vocal morphology and control. A particular developmental period of interest would be between late childhood and into early adolescence, given that social evaluation concerns increase during this period [50], though emerging anatomical differences between females and males would also need to be taken into account [17]. It would also be worth investigating to what extent the observed vocal modulation for self-presentational purposes occurs in the early years, given that 5- to 6-year olds show a relatively limited cognitive capacity for understanding self-presentational motives [12], though they do have the ability to control their voice to alter the expression of their gender [29].

Another goal for future research would be to explore whether children differ in the degree of voice manipulation according to other characteristics of the audience and the nature of the interaction taking place, beyond the current focus on making friends with a hypothetical peer audience. Responses to vignettes are clearly valuable for gaining an insight into children's self-presentational motivations (i.e. [51]). However, when making friends in real life, aspects of individuals' vocal productions may not be under voluntary control. For example, an increase in anxiety is associated with higher F0 [52]. Thus, future research could use naturalistic or structured observation of children's behaviour to increase the ecological validity of its findings.

Moreover, we already know that different social agents (e.g. parents: [53]; teachers: [54]; peers: [55]) influence children's conformity to gender norms. So it is possible that children will respond differently to more narrowly specified categories of the audience (e.g. friends versus non-friends; familiar versus unfamiliar; teachers versus parents). The development of children's self-presentation is also known to vary systematically in relation to contextual factors. Such factors include reputation management following rule violations and acceptance and self-enhancement with members of one's social group versus out-group members [25], as well as children's perceptions of themselves (e.g. social influence and status) and of others [56]. It would be instructive to evaluate the extent to which spontaneous manipulations of vocal qualities take place in these different kinds of social interactions with both peer and adult audiences.

To understand how the voice manipulations we observed map onto listeners' perceptions, studies could evaluate the success of these self-presentational efforts in terms of audience responses (e.g. peer behavioural attributions and friendship choices), particularly given that we already have evidence that child listeners attribute masculinity and femininity on the basis of shifts in voice frequency cues [18]. As well as cues to masculinity and femininity, psychoacoustic research with adults suggests that F0 and ΔF can affect the perception of other social traits, including dominance and trustworthiness [57–59], which are also important in attempts to establish friendship. Future research could therefore investigate whether children's variation in vocal masculinity and femininity could also have broader effects on audience attributions along with a range of different personal dimensions, and their possible impact on children's popularity and likeability in peer contexts.

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the Sciences and Technology Cross-Schools Research Ethics Committee (C-REC) of the University of Sussex (code: ER/VC44/8).

Data accessibility

Data can be accessed on Figshare: https://figshare.com/s/d619d682c54f5f87c2d0 [60].

Authors' contributions

V.C. participated in the data collection, contributed to the design, performed acoustic and statistical analyses, wrote the manuscript and created the figures; D.R., A.G. and J.O. contributed to the design of the investigation; R.B. conceived of the study, participated in the design and analyses, and helped draft the manuscript. The manuscript was reviewed, edited and approved by all authors, who agree to be accountable for the work.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by Leverhulme Trust (grant no. RPG-2016-396).

References

- 1.Maccoby E. 1990. Gender and relationships: a developmental account. Am. Psychol. 45, 513-520 ( 10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.513) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta C, Strough J. 2009. Sex segregation in friendships and normative contexts across the life span. Dev. Rev. 29, 201-220 ( 10.1016/j.dr.2009.06.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erwin P. 1993. Friendship and peer relations in children. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottman JM, Parker JG. 1986. Conversations of friends: speculations on affective development. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin C, Kornienko O, Schaefer D, Hanish L, Fabes R, Goble P. 2012. The role of sex of peers and gender-typed activities in young children's peer affiliative networks: a longitudinal analysis of selection and influence. Child Dev. 84, 921-937. ( 10.1111/cdev.12032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorne B. 1993. Gender play: girls and boys in school. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skočajić MM, Radosavljević JG, Okičić MG, Janković IO, Žeželj IL. 2020. Boys just don't! Gender stereotyping and sanctioning of counter-stereotypical behavior in preschoolers. Sex Roles 82, 163-172 ( 10.1007/s11199-019-01051-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serbin LA, Connor JM. 1979. Sex-typing of children's play preferences and patterns of cognitive performance. J. Genet. Psychol. 134, 315-316 ( 10.1080/00221325.1979.10534065) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee R, Lintern V. 2000. Boys will be boys: the effect of social evaluation concerns on gender-typing. Soc. Dev. 9, 397-408. ( 10.1111/1467-9507.00133) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A, Bussey K. 2004. On broadening the cognitive, motivational, and sociostructural scope of theorizing about gender development and functioning: comment on Martin, Ruble, and Szkrybalo (2002). Psychol. Bull. 130, 691-701. ( 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaughn BE, Kopp CB, Krakow JB. 1984. he emergence and consolidation of self-control from eighteen to thirty months of age: normative trends and individual differences. Child Dev. 55, 990-1004. ( 10.2307/1130151) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee R, Yuill N .1999. Children's understanding of self-presentational display rules: associations with mental-state understanding. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 17, 111-124. ( 10.1348/026151099165186) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aloise-Young PA. 1993. The development of self-presentation: self-promotion in 6-to 10-year-old children. Soc. Cogn. 11, 201-222 ( 10.1521/soco.1993.11.2.201) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee R. 2002. Audience effects on self-presentation in childhood. Soc. Dev. 11, 487-507. ( 10.1111/1467-9507.00212) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Potamianos A, Narayanan S. 1999. Acoustics of children's speech: developmental changes of temporal and spectral parameters. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105, 1455-1468. ( 10.1121/1.426686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry TL, Ohde RN, Ashmead DH. 2001. The acoustic bases for gender identification from children's voices. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109, 2988-2998. ( 10.1121/1.1370525) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vorperian HK, Kent RD. 2007. Vowel acoustic space development in children: a synthesis of acoustic and anatomic data. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 50, 1510-1545 ( 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartei V, Banerjee R, Hardouin L, Reby D. 2019. The role of sex-related voice variation in children's gender-role stereotype attributions. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 37, 396-409 ( 10.1111/bjdp.12281) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cartei V, Garnham A, Oakhill J, Banerjee R, Roberts L, Reby D. 2019. Children can control the expression of masculinity and femininity through the voice. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 190656. ( 10.1098/rsos.190656) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacEvoy JP, Asher SR. 2012. When friends disappoint: boys' and girls’ responses to transgressions of friendship expectations. Child Dev. 83, 104-119. ( 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01685.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coplan RJ, Girardi A, Findlay LC, Frohlick SL. 2007. Understanding solitude: young children's attitudes and responses toward hypothetical socially withdrawn peers. Soc. Dev. 16, 390-409. ( 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00390.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felmlee DH. 1999. Social norms in same-and cross-gender friendships. Soc. Psychol. Q. 62, 53-67. ( 10.2307/2695825) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deaux K, Major B. 1987. Putting gender into context: an interactive model of gender-related behavior. Psychol. Rev. 94, 369. ( 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.369) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vorperian HK, Wang S, Schimek EM, Durtschi RB, Kent RD, Gentry LR, Chung MK. 2011. Developmental sexual dimorphism of the oral and pharyngeal portions of the vocal tract: an imaging study. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 54, 995-1010. ( 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0097) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee R, Heyman GD, Lee K. 2020. The development of moral self-presentation. In The Oxford handbook of moral development: an interdisciplinary perspective (ed. Jensen LA), pp. 92-109. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin CL, Wood CH, Little LK. 1990. The development of gender stereotype components. Child Dev. 61, 1891-1904. ( 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb03573.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boersma P, Weenink D. 2014. Praat: doing phonetics by computer. See http://www.praat.org (accessed 2019).

- 28.Reby D, McComb K. 2003. Anatomical constraints generate honesty: acoustic cues to age and weight in the roars of red deer stags. Anim. Behav. 65, 519-530 ( 10.1006/anbe.2003.2078) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cartei V, Cowles W, Banerjee R, Reby D. 2014. Control of voice gender in pre-pubertal children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 32, 100-106. ( 10.1111/bjdp.12027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox J. 2016. Bootstrapping regression models. In Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models (ed. Fox J), pp. 587-606, 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 31.RStudio Team. 2020. RStudio: integratrd development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, PBC. See http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 32.IBM Corp. 2016. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saarni C. 1979. Children's understanding of the display rules for expressive behavior. Dev. Psychol. 15, 424-429. ( 10.1037/0012-1649.15.4.424) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camras LA. 1984. Children's verbal and nonverbal communication in a conflict situation. Ethol. Sociobiol. 5, 257-268 ( 10.1016/0162-3095(84)90005-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis TL. 1995. Gender differences in masking negative emotions: ability or motivation? Dev. Psychol. 3, 660. ( 10.1037/0012-1649.31.4.660) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zivin G. 1982. Watching the sands shift: conceptualizing development of nonverbal mastery. In Development of nonverbal behavior in children (ed. RS Feldman), pp. 63-98. New York, NY: Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Underwood MK, Coie JD, Herbsman CR. 1992. Display rules for anger and aggression in school-age children. Child Dev. 63, 366-380 ( 10.2307/1131485) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leaper C. 2011. More similarities than differences in contemporary theories of social development? A plea for theory bridging. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 40, 337-378. ( 10.1016/B978-0-12-386491-8.00009-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cartei V, Oakhill J, Garnham A, Banerjee R, Reby D. 2020. ‘This is what a mechanic sounds like’: children's vocal control reveals implicit occupational stereotypes. Psychol. Sci. 31, 957-967. ( 10.1177/0956797620929297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cvencek D, Meltzoff AN, Greenwald AG. 2011. Math–gender stereotypes in elementary school children. Child Dev. 82, 766-779. ( 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01529.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White MJ, White GB. 2006. Implicit and explicit occupational gender stereotypes. Sex roles 55, 259-266. ( 10.1007/s11199-006-9078-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sityaev D, Webster G, Braunschweiler N, Buchholz S, Knill K. 2007. Some aspects of prosody of friendly formal and friendly informal speaking styles. In XVI Int. Conf. on Phonetics Sciences, Saarbrücken, pp. 6-10. Saarbrücken, Germany: University des Saarlandes. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knowles KK, Little AC. 2016. Vocal fundamental and formant frequencies affect perceptions of speaker cooperativeness. Q J. Exp. Psychol. (Colchester) 69, 1657-1675. ( 10.1080/17470218.2015.1091484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sachs J, Lieberman P, Erickson D. 1973. Anatomical and cultural determinants of male and female speech. In Language attitudes: current trends and prospects (eds Shuy RW, Fasold RW), pp. 74-84. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaFrance M, Hecht MA, Paluck EL. 2003. The contingent smile: a meta-analysis of sex differences in smiling. Psychol. Bull. 129, 305. ( 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dodd DK, Russell BL, Jenkins C. 1999. Smiling in school yearbook photos: gender differences from kindergarten to adulthood. Psychol. Rec. 49, 543-553. ( 10.1007/BF03395325) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma EPM, Lam NLN. 2015. Speech task effects on acoustic measure of fundamental frequency in Cantonese-speaking children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 79, 2260-2264. ( 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.10.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vogel AP, Fletcher J, Snyder PJ, Fredrickson A, Maruff P. 2011. Reliability, stability, and sensitivity to change and impairment in acoustic measures of timing and frequency. J. Voice 25, 137-149. ( 10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.09.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. 2010. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 466, 29-29. ( 10.1038/466029a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westenberg PM, Drewes MJ, Goedhart AW, Siebelink BM, Treffers PDA. 2004. A developmental analysis of self-reported fears in late childhood through mid-adolescence: social-evaluative fears on the rise? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 481-495. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00239.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banerjee R, Dittmar H. 2008. Individual differences in children's materialism: the role of peer relations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 17-31. ( 10.1177/0146167207309196) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laukka P, et al. 2008. In a nervous voice: acoustic analysis and perception of anxiety in social phobics' speech. J. Nonverb. Behav. 32, 195-214. ( 10.1007/s10919-008-0055-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leaper C. 2000. Gender, affiliation, assertion, and the interactive context of parent–child play. Dev. Psychol. 36, 381-393. ( 10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.381) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alan S, Ertac S, Mumcu I. 2018. Gender stereotypes in the classroom and effects on achievement. Rev. Econ. Stat. 100, 876-890. ( 10.1162/rest_a_00756) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braun SS, Davidson AJ. 2017. Gender (non) conformity in middle childhood: a mixed methods approach to understanding gender-typed behavior, friendship, and peer preference. Sex Roles 77, 16-29. ( 10.1007/s11199-016-0693-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salmivalli C, Ojanen T, Haanpää J, Peets K. 2005. ‘I'm OK but you're not’ and other peer-relational schemas: explaining individual differences in children's social goals. Dev. Psychol. 41, 363. ( 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.363) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hodges-Simeon CR, Gaulin SJ, Puts DA. 2010. Different vocal parameters predict perceptions of dominance and attractiveness. Hum. Nat. 21, 406-427. ( 10.1007/s12110-010-9101-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Connor JJ, Barclay P. 2017. The influence of voice pitch on perceptions of trustworthiness across social contexts. Evol. Hum. Behav. 38, 506-512. ( 10.1016/J.EVOLHUMBEHAV.2017.03.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oleszkiewicz A, Pisanski K, Lachowicz-Tabaczek K, Sorokowski A. 2017. Voice-based assessments of trustworthiness, competence, and warmth in blind and sighted adults. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24, 856-862. ( 10.3758/s13423-016-1146-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cartei V, Reby D, Garnham A, Oakhill J, Banerjee R. 2021. Peer audience effects on children's vocal masculinity and femininity. Figshare. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessed on Figshare: https://figshare.com/s/d619d682c54f5f87c2d0 [60].