This randomized clinical trial tests the hypothesis that n-of-1 trials of self-selected atrial fibrillation triggers would enhance atrial fibrillation–related quality of life.

Key Points

Question

Can n-of-1 trials of self-selected triggers of atrial fibrillation (AF) improve AF-related quality of life?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 466 patients, participating in n-of-1 trials was found not to improve AF-related quality of life but led to fewer subsequent AF episodes compared with controls. No trigger was associated with AF in intention-to-treat analyses; in per-protocol analyses, alcohol heightened the likelihood of AF, whereas other triggers, including caffeine, revealed no relationships with AF.

Meaning

n-of-1 trigger testing did not enhance AF-related quality of life but reduced the number of AF episodes; alcohol, but not caffeine, increased the risk of AF events.

Abstract

Importance

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia. Although patients have reported that various exposures determine when and if an AF event will occur, a prospective evaluation of patient-selected triggers has not been conducted, and the utility of characterizing presumed AF-related triggers for individual patients remains unknown.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that n-of-1 trials of self-selected AF triggers would enhance AF-related quality of life.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized clinical trial lasting a minimum of 10 weeks tested a smartphone mobile application used by

symptomatic patients with paroxysmal AF who owned a smartphone and were interested in testing a presumed AF trigger. Participants were screened between December 22, 2018, and March 29, 2020.

Interventions

n-of-1 Participants received instructions to expose or avoid self-selected triggers in random 1-week blocks for 6 weeks, and the probability their trigger influenced AF risk was then communicated. Controls monitored their AF over the same time period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

AF was assessed daily by self-report and using a smartphone-based electrocardiogram recording device. The primary outcome comparing n-of-1 and control groups was the Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life (AFEQT) score at 10 weeks. All participants could subsequently opt for additional trigger testing.

Results

Of 446 participants who initiated (mean [SD] age, 58 [14] years; 289 men [58%]; 461 White [92%]), 320 (72%) completed all study activities. Self-selected triggers included caffeine (n = 53), alcohol (n = 43), reduced sleep (n = 31), exercise (n = 30), lying on left side (n = 17), dehydration (n = 10), large meals (n = 7), cold food or drink (n = 5), specific diets (n = 6), and other customized triggers (n = 4). No significant differences in AFEQT scores were observed between the n-of-1 vs AF monitoring-only groups. In the 4-week postintervention follow-up period, significantly fewer daily AF episodes were reported after trigger testing compared with controls over the same time period (adjusted relative risk, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43- 0.83; P < .001). In a meta-analysis of the individualized trials, only exposure to alcohol was associated with significantly heightened risks of AF events.

Conclusions and Relevance

n-of-1 Testing of AF triggers did not improve AF-associated quality of life but was associated with a reduction in AF events. Acute exposure to alcohol increased AF risk, with no evidence that other exposures, including caffeine, more commonly triggered AF.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03323099

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia and results in substantial morbidity.1 The majority of research regarding the origins of AF has concentrated on determinants of an AF diagnosis rather than on acute factors that influence the risk of an AF event.2 Although patients report that certain exposures influence the chance an AF episode will occur,3 the effects of triggers on discrete episodes of AF have not been systematically evaluated.

As studies of populations only reveal differences in mean values across groups, only an n-of-1 study can demonstrate how any given individual will react to a particular intervention.4 An n-of-1 study requires a modifiable exposure with a fairly immediate effect and a recurrent disease that is (1) frequent enough, (2) reliably detectable, and (3) not catastrophic.5,6,7 Symptomatic, paroxysmal AF would appear to be well suited to such n-of-1 studies.

Methods

The I-STOP-AFib (Individualized Studies of Triggers of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation) trial was designed by investigators and patients with AF (G.M.M., M.F.M., K.S., M.T.H., D.M., K.S., and I.S.) during the 2014 Health eHeart Alliance Patient-Powered Research Summit, a brainstorming session funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Patients identified individual-level triggers for AF episodes as their highest research priority. A patient advisory board was involved throughout the entire process. The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco institutional review board. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 1.

We conducted a remote, smartphone mobile application–based randomized clinical trial that randomly assigned patients with paroxysmal AF 1:1 to individualized (n-of-1) trigger testing vs AF monitoring alone. The mobile application was developed, launched, and maintained using the National Institutes of Health–supported Eureka Research Platform8 at the University of California, San Francisco. Symptomatic patients with AF who were 18 years or older, owned a smartphone (either Android or iOS), and were interested in testing a presumed AF trigger they could readily introduce or withhold were eligible. Individuals who planned to change their AF management (eg, with catheter ablation or medication changes) in the subsequent 6 months, did not speak English, or who had undergone an atrioventricular junction ablation were excluded. Participants were recruited through emailed invitations (from the Health eHeart Study and StopAfib.org subscribers), social media invitations, word of mouth, and individual health care professionals.

The workflow for participants is shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. Participants were screened between December 22, 2018, and March 29, 2020. After providing informed electronic consent, participants were shipped a mobile electrocardiogram (ECG) recording device (KardiaMobile; AliveCor), which pairs with smartphones. All ECG strips flagged as possible AF by the device’s US Food and Drug Administration–cleared AF detection algorithm during the initial (first period) n-of-1 tests were overread by a board-certified cardiologist and designated as AF or not (ECG recordings beyond the first treatment period were not available). After randomization to either individualized (n-of-1) trigger testing or AF monitoring only, participants completed the validated Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life (AFEQT) questionnaire.9 Participants were queried daily regarding episodes of AF and instructed to use the mobile ECG device daily and whenever they had symptoms of AF. Data on race and ethnicity were self-reported.

Participants randomized to the n-of-1 trial arm were instructed to select a trigger they wished to test using a menu informed by commonly reported triggers determined by survey of patients with AF in the Health eHeart Study,3 including an option to write in free-text triggers. As explicitly described in the study consent, participants were not asked to expose themselves to triggers they would not encounter within the course of their normal lives. Participants undertook six 1-week periods of trigger exposure or nonexposure. Daily text messages instructed participants to expose themselves to the trigger at some point during that week during trigger-on weeks or to avoid the trigger during the trigger-off weeks. The 6 periods were randomly assigned in 3 blocks of trigger on/trigger off or trigger off/trigger on. They received daily queries regarding trigger exposure during the previous day to inform per-protocol analyses. At the end of each trial, the probability their presumed trigger influenced the chance of an AF episode was calculated by statistical algorithms described below; this was communicated to the participant along with their reported AF episodes illustrated on a calendar by trigger testing vs avoidance assignments (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). They were then instructed to implement lifestyle changes they deemed appropriate based on what they learned from the n-of-1 trial results. They were then observed for an additional 4 weeks. At the end of this final 4-week lifestyle change period, participants were asked to again complete the AFEQT survey. Those in the monitoring arm received the same frequency and type of text messages to ascertain daily AF for a total of 10 weeks and then repeated the AFEQT assessment.

After the initial 10-week study period, all participants were given the option to end study participation or test up to 4 additional triggers. Each of these 10-week experiences are referred to as successive study periods. Adverse events, including hospitalizations and emergency department visits, were determined monthly.

Normally distributed continuous variables are described as means (SDs) and compared via t tests. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests. The primary study outcome was AF-related quality of life, measured by the AFEQT. The number of AF events during the final 4 weeks of the initial study period, corresponding with a postintervention period, was a secondary outcome.

As previous evidence suggests that those with moderate AF severity have a mean (SD) AFEQT score of 58 (19) and therapies typically improve this score by a mean of 5 to 10,9 we estimated 239 patients in each group would provide 80% power to detect a mean change of 5 AFEQT points using a 2-sided α of .05.

Differences in AFEQT between the 2 randomized groups were estimated using analysis of covariance with the 10-week measurement as the outcome and the baseline measurement as covariate. Counts of days with AF were assessed using a negative binomial model. We adjusted for covariates that were not equally balanced between randomization groups as well as differences in baseline characteristics among those with and without 10-week measurements to account for missing data. Group comparisons were tested at a 2-tailed significance level of .05.

To obtain the probability a trigger influenced AF, daily AF was analyzed as a binary event using a bayesian generalized linear model, adjusted for autocorrelation using noninformative prior distributions with intention-to-treat and per-protocol approaches. Days on which AF was unreported were analyzed in 2 ways: by dropping the missing days and by imputing no events to those days. n-of-1 trial results were reported as odds ratios with 95% bayesian credible intervals and posterior probabilities that the odds ratio was greater than 1. We considered differences to be significant if the 95% credible intervals did not include 1. A 1-tailed posterior probability of more than 0.975 was considered statistically significant.

AF events during n-of-1 trials were analyzed individually and by meta-analysis combining across different trials. Per-protocol analyses reflected each participant’s behavior with respect to trigger instruction based on their self-report (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

AF events during n-of-1 trials were analyzed by meta-analysis combining data across different trials. We conducted separate meta-analyses of each set of n-of-1 trials that tested a particular trigger where at least 1 assessment was completed during both trigger exposure and avoidance. The meta-analytic model provided an adjusted treatment effect for each individual that accounted for the average treatment effect across participants.

To compare the effects of the different triggers, we carried out a network meta-analysis10 combining all trials that compared 1 trigger with no exposure. The network was constructed combining all the trials for a patient into 1 trial with several arms, 1 for each different trigger, and 1 for no trigger that combined all the results from the no trigger arms. Thus, comparisons between triggers combined direct comparisons within participants and indirect comparisons across participants who shared the same no exposure group.

Details of the statistical models for both the individual, meta-analysis, and network meta-analysis are provided in the eAppendix in Supplement 2. Open-source R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation) incorporated data from the Eureka platform, created the bayesian models and identified starting values for modeling, which were fed into open-source JAGS software using the rjags package. The remainder of statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

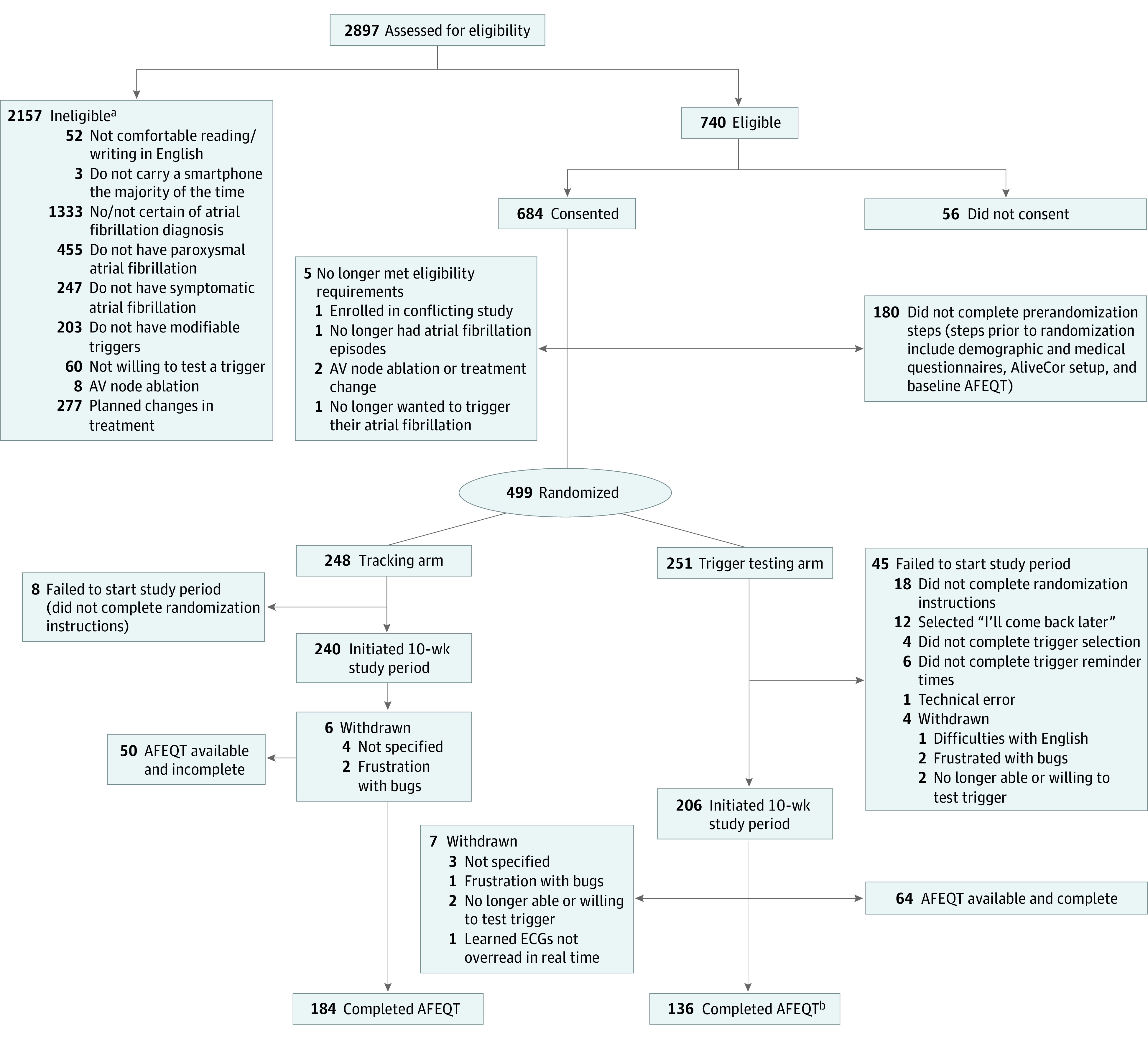

Of 2987 individuals, 740 were eligibile, 684 consented, 499 began randomization activities, and 446 completed activities required for randomization (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics in each randomization arm are listed in Table 1. More than half were men (289 [58%]), and the majority were White (461 [92%]). Those in the trigger arm exhibited a higher baseline mean AFEQT score (less severe AF) and were more often college educated.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram of Participant Screening, Consent, Randomization, and Study Completion.

AV indicates atrioventricular; AFEQT, Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life; ECG, electrocardiogram.

aReasons for ineligibility are not mutually exclusive.

bIncludes 1 participant who did not initiate 10-week period.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Arm, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger testing (n = 251) | Monitoring only (n = 248) | |

| Baseline AFEQT score, mean (SD) | 74 (19) | 72 (19) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58 (14) | 58 (14) |

| Height, mean (SD), ft | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.4) |

| Weight, mean (SD), lb | 193 (49) | 195 (47) |

| Male | 149 (59) | 140 (56) |

| Female | 102 (40) | 108 (44) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 12 (5) | 9 (3) |

| Black | 2 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Hispanic | 16 (6.4) | 8 (3.2) |

| White | 233 (92) | 228 (93) |

| Othera | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | 4 (2) |

| Education | ||

| ≥Undergraduate degree | 187 (74) | 153 (62) |

| Some college | 52 (21) | 64 (26) |

| ≤High school | 10 (4) | 25 (10) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Household income | ||

| <$20 000 | 26 (10) | 32(13) |

| $20 000-<$40 000 | 47 (19) | 48 (19) |

| $40 000-<$75 000 | 79 (31) | 91 (37) |

| $75 000-<$150 000 | 74 (29) | 50 (20) |

| ≥$150 000 | 26 (10) | 27 (11) |

| Taking a Vaughan-Williams class 1 or 3 drug | 57 (23) | 68 (27) |

| Hypertension | 104 (41) | 109 (44) |

| Diabetes | 18 (7) | 29 (12) |

| Coronary artery disease | 28 (11) | 27 (11) |

| History of myocardial infarction | 8 (3) | 11 (4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 12 (5) | 16 (7) |

| History of stroke | 16 (6) | 24 (10) |

| Sleep apnea | 78 (31) | 75 (30) |

Abbreviation: AFEQT, Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life.

Individuals self-reported “other.”

Of 446 participants who initiated their randomized assignment, 320 (72%) completed all study activities. Triggers selected during the initial n-of-1 assessment period included caffeine (n = 53), alcohol (n = 43), reduced sleep (n = 31), exercise (n = 30), lying on left side (n = 17), dehydration (n = 10), large meals (n = 7), cold food or drink (n = 5), specific diets (n = 6), and customized triggers (n = 4; customized triggers selected are shown in eTable 2 in Supplement 2). No significant differences in the adjusted 10-week AFEQT scores were observed between the randomized trigger testing and monitoring-only groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Differences in Change in AFEQT Between n-of-1 and Atrial Fibrillation Monitoring Groups.

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Trigger testing arm (n = 136) | |

| Baseline AFEQT | 76.1 (16.8) |

| 10-wk AFEQT | 77.9 (19.6) |

| AFEQT difference | 1.7 (13.0) |

| Monitoring-only arm (n = 184) | |

| Baseline AFEQT | 72.4 (19.1) |

| 10-wk AFEQT | 72.9 (18.7) |

| AFEQT difference | 0.5 (14.1) |

| Difference in 10-wk AFEQT between arms, mean (95% CI) | |

| Adjusted for baseline AFEQT | |

| With educationa | 2.1 (−0.9 to 5.0)b |

| With age and race and ethnicityc | 2.1 (−0.0 to 5.0))b |

Abbreviation: AFEQT, Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life.

Adjusted for baseline differences between groups.

P = .17.

Adjusted for baseline differences and differences among those with missing data.

In the first study period, a total of 153 participant days with AF were detected using the mobile ECG and 544 participant days included self-reported AF (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Those randomized to n-of-1 testing self-reported 40% fewer AF events in the 4 weeks following receiving the results of their n-of-1 study compared with monitoring-only participants during the same time frame (adjusted relative risk, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.83; P < .001; eTable 4 in Supplement 2). This reduction was driven by those in the n-of-1 group who tested alcohol, dehydration, and exercise (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). No significant differences were found comparing reports by the mobile ECG device, but differences also favored the trigger testing group (adjusted relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.41-1.51; P = .47) with a much lower event rate (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). Few adverse events were observed without differences between randomized groups (eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

For all study periods, 326 participants conducted 474 trials testing various triggers: caffeine (n = 100), alcohol (n = 82), exercise (n = 75), reduced sleep (n = 66), lying on left side (n = 42), dehydration (n = 37), cold food or drink (n = 9), large meals (n = 29), specific diets (n = 17), and customized triggers (n = 17) (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). Differences in participant characteristics by trigger selection are shown in eTable 8 in Supplement 2. Compliance with trigger assignment was more common than not, but failure to report was common (eTable 9 in Supplement 2).

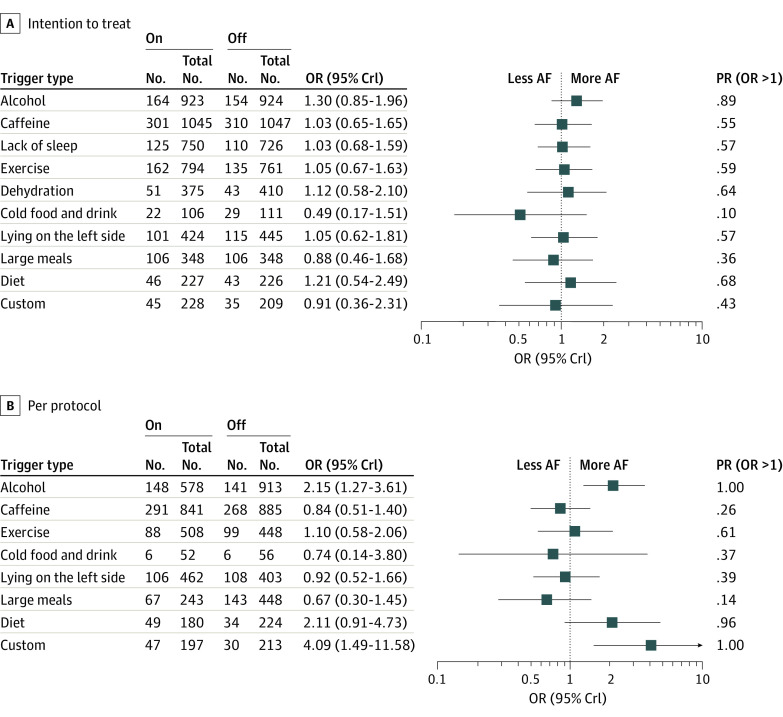

When restricted to the primary n-of-1 period, no statistically significant relationships between meta-analyses of any trigger exposure and AF were observed for either self-reported or mobile ECG outcomes (eTable 10 in Supplement 2). In meta-analyses including all n-of-1 tests performed during all periods, no differences in AF were observed according to intention-to-treat assessment of trigger assignments. However, acute exposure to alcohol in the per-protocol analysis was associated with a statistically significant nearly 80% increased odds of a self-reported AF event (Table 3). Similarly, in the network meta-analysis, no statistically significant associations with AF were observed using intention-to-treat analyses, but both alcohol and customized triggers were associated with more reported AF on days when participants reported trigger exposure vs avoidance (Figure 2).

Table 3. Summary Estimates of Odds of Self-reported AF During Trigger Exposure vs Avoidance Using All n-of-1 Trials Across All Time Periods.

| Variable | Odds of self-reported AF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to treat | Per protocol | |||

| OR (95% CrI)a | Pr (OR >1) | OR (95% CrI)a | Pr (OR >1) | |

| Alcohol | 1.17 (0.81-1.72) | 0.81 | 1.77 (1.20-2.69) | 1.00 |

| Caffeine | 1.01 (0.68-1.45) | 0.51 | 0.95 (0.58-1.55) | 0.42 |

| Lack of sleep | 1.03 (0.71-1.53) | 0.55 | NAb | NAb |

| Exercise | 1.05 (0.64-1.68) | 0.57 | 1.02 (0.50-1.95) | 0.52 |

| Dehydration | 1.73 (0.61-4.06) | 0.87 | NAb | NAb |

| Cold food or drink | 0.53 (0.14-2.03) | 0.14 | 0.85 (0.08-10.27) | 0.43 |

| Lying on left side | 1.00 (0.51-2.09) | 0.51 | 0.81 (0.38-1.63) | 0.29 |

| Large meals | 0.92 (0.51-1.65) | 0.39 | 0.63 (0.22-1.40) | 0.12 |

| Custom | 1.01 (0.22-3.49) | 0.51 | 6.30 (0.83-23.90) | 0.97 |

| Diet | 1.34 (0.28-5.49) | 0.65 | 3.46 (0.68-12.13) | 0.94 |

| Trigger avoidance | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CrI, credible intervals; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; Pr (OR >1), posterior probabilities that the odds ratio was greater than 1.

95% Bayesian credible interval formed as 2.5 and 97.5 percentile of posterior distribution.

Per-protocol criteria were not ascertained during the study (see Methods).

Figure 2. Network Meta-analyses Odds Ratios for Self-reported AF During Trigger Exposure vs Avoidance in Intention to Treat and Per Protocol Combining All n-of-1 Trials Throughout the Study.

Numbers indicate number of events/number of days reported. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; Crl, credible interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

We found little evidence that undergoing personalized n-of-1 trials to inform patients about the influence of presumed self-selected AF triggers improved AF-related quality of life.9 However, the number of self-reported AF episodes after completion of n-of-1 trials was substantially and statistically significantly lower compared with the frequency among those randomized to monitor their AF over the same time period; those selecting to test alcohol, dehydration, and exercise drove that difference. No differences in mobile ECG-detected AF episodes were detected. Finally, during n-of-1 testing, consumption of alcohol was the only trigger consistently observed to result in significantly more self-reported AF episodes.

The current project stemmed from an unmet need identified by patients with AF. Since the initial conception of the study, lifestyle factors related to AF risk have emerged as a central topic pertinent to AF management according to multiple professional societies11,12 and a research priority for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.13

The explanation for the discrepancy between the AFEQT result and the finding of a reduced number of self-reported AF episodes in the trigger testing group is unclear. It is possible the AFEQT, a summary of the previous month that relies on remembering those details, is prone to recall bias, while the more real-time (daily) AF assessments may better reflect actual patient experience. However, the AFEQT also incorporates additional information, such as the severity of AF episodes and quantification of adverse effects of AF on quality of life. Although the number of randomized patients achieved our goal based on our power calculations, the total number completing the follow-up AFEQT did not, and therefore insufficient power may also explain the null result.

There were no circumstances where trigger exposure assessed as intention to treat was associated with AF. Participants followed instructions more often than not, but a substantial number of daily surveys were not answered. This may also point to a challenge of smartphone– or mobile health–based n-of-1 studies, where repeated and frequent engagement is required. Understanding that patients may not want to repeatedly expose themselves to a trigger that could be harmful (or cause AF and lead them to miss work on a work day for example), we instructed participants to expose themselves to the trigger at some point during an assigned trigger week; however, our conservative intention-to-treat analyses examined each day as if it were associated with trigger exposure vs avoidance. Therefore, the per-protocol analyses may better reflect the influence of triggers on acute AF events.

During the n-of-1 tests, alcohol emerged as the only trigger where exposure was consistently associated with more episodes of self-reported AF. Because the mobile ECG–based AF assessments were only conducted for the first time period, that outcome assessment was not available for the analyses of all n-of-1 trials. There were substantially fewer events detected by the ECG device, which may have reduced power to detect associations using that method of outcome ascertainment. Previous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that alcohol is a risk factor for the development of AF,14,15,16 and a recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated that patients with AF instructed to abstain from alcohol had a lower burden of AF over time.17 While the majority of this work has focused on chronic effects, recent evidence has revealed both acute atrial electrophysiologic changes in a randomized clinical trial18 and nearly contemporaneous relationships between alcohol and AF among continuously monitored, ambulatory individuals.19

Caffeine was the most commonly selected trigger for testing but failed to exhibit any relationships with AF. Recent literature has similarly failed to demonstrate a relationship between caffeine and arrhythmias20 and potentially even a protective effect related to AF.21 These past studies focused on long-term effects, and studies examining acute, or real-time, effects are sparse. These findings highlight a potential advantage of n-of-1 research: the ability to reassure patients that a particular exposure (including a potentially enjoyable one like caffeine) is not important in their disease.

Other statistically significant relationships were observed in the network meta-analysis, where exposure to a customized trigger was associated with more self-reported AF. This may suggest that the fruitful pursuit of n-of-1 studies in AF may lie in greater specification of triggers idiosyncratic to each individual. Patients with AF may report more than 1 trigger, and the network meta-analysis was constructed to accommodate all of the various trigger tests throughout the study (including when more than 1 trigger was tested within a given participant).

Limitations

Several other limitations should be considered. Although we reached our target recruitment goal, there was attrition during the study. However, retention was high when compared with other remote-only mobile application–based randomized studies.22,23,24 Analyses were adjusted to address differences in characteristics among those with and without missing data and sensitivity analyses wherein an absence of a report was conservatively imputed as no AF revealed no meaningful differences. As the study was not blinded, dropout was differential owing to differences in baseline characteristics in those with and without missing data. A sham arm could have been used as an approach to mitigate differences in missing data between randomized groups. The current study, allowing participants to select from a variety of options regarding messaging and their triggers, was likely too complex. A more focused, uniformly constructed, and simple study may have enhanced feasibility, engagement, and retention, helping to reduce attrition and incomplete data capture in general. Participants did not wear continuously recording ECG devices, which would have enhanced sensitivity. Self-reported AF may have reflected a sensation of AF during a normal rhythm or only the exacerbation of symptomatic AF that was otherwise occult. Participants ultimately had to decide when to record an ECG based on the system used, and their knowledge of the presumed trigger that they themselves selected could have influenced whether they chose to record an ECG (for example, after consuming alcohol only because of their extant beliefs). The study by definition included individuals motivated to test triggers they believed influenced symptoms of AF, which may introduce bias regarding the trigger types selected and effects on AF (symptomatic or not) that may occur in the broader AF population at large. We relied on participant self-report to describe compliance with their triggers. It is important to note that the study was designed to detect effects of potential triggers assumed to manifest consequences within a day of exposure, whereas the effects of more chronic exposures, such as prolonged sleep deprivation, may have had too long of a time horizon to be detected. The network meta-analysis worked under the assumption that everyone had the same chance to receive a particular treatment (in this case, the same trigger), which was not necessarily the case given participant differences that may have influenced the selection of a specific trigger. The network meta-analysis also assumes that the same treatment (ie, the same trigger) would have the same effects for different individuals, which also may not be the case given the supposition that AF trigger effects may be fairly idiosyncratic to each person. Finally, our population was predominately White and highly educated, which may limit extrapolation to the general population. Future efforts among remote and technology-based studies should ideally include support for dedicated efforts to recruit a more diverse population.

Although the primary outcome was not different between groups, we do not believe the publication of this current trial should close the door to subsequent attempts to elucidate the utility of identifying individual-level AF triggers. We hope the current study may provide lessons learned and motivate future efforts to refine these processes to help patients arrive at more definitive and clinically useful results. For example, some objective evidence of a relationship between a particular trigger and AF could first be required; some objective ascertainment of exposure to the trigger of interest, such as via sensors, could be used; continuous ECG monitoring would help with both sensitivity and specificity in ascertaining the outcome, which may be most feasibly accomplished with a wearable device (such as a smartwatch25,26).

Conclusions

We failed to detect definitive evidence that n-of-1 testing of participant-selected AF triggers improved AF-related quality of life. However, those undergoing n-of-1 testing subsequently reported AF less often compared with a control group. Although caffeine was the most common trigger selected for testing, only alcohol exhibited consistent evidence of a near-term effect on self-reported AF episodes. These data suggest that certain behaviors may influence the chance a discrete AF will occur, but there is currently insufficient evidence to support individualized trigger testing to improve quality of life in AF.

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan.

eFigure 1. Overall Study Design and Workflow

eFigure 2. Example of Results Communicated to a Participant After Completion of their 6-Week N-of-1 Testing

eTable 1. Using answers to daily compliance questions during N-of-1 testing to inform per-protocol analyses

eTable 2. Specific customized triggers

eTable 3. Self-reported atrial fibrillation versus mobile ECG-detected atrial fibrillation during the primary study period (participant days)

eTable 4. Differences in daily AF episodes between N-of-1 and AF monitoring groups

eTable 5. Relative risks of self-reported AF during the last 4 weeks of the first 10-week treatment period comparing each individual trigger to the AF monitoring-only group

eTable 6. Differences in adverse events between N-of-1 and AF monitoring groups

eTable 7. Study participants contributing to trigger exposure versus avoidance meta-analyses from all study periods

eTable 8. Differences in Participant Characteristics by Trigger Selection

eTable 9. Trigger testing compliance by trigger type

eTable 10. Summary odds ratios for self-reported AF and AliveCor events for trigger exposure versus avoidance during the first N-of-1 trial period only

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staerk L, Sherer JA, Ko D, Benjamin EJ, Helm RH. Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. Circ Res. 2017;120(9):1501-1517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groh CA, Faulkner M, Getabecha S, et al. Patient-reported triggers of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(7):996-1002. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schork NJ. Personalized medicine: time for one-person trials. Nature. 2015;520(7549):609-611. doi: 10.1038/520609a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirza RD, Guyatt GH. A randomized clinical trial of n-of-1 trials: tribulations of a trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1378-1379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson KW, Silverstein M, Cheung K, Paluch RA, Epstein LH. Experimental designs to optimize treatments for individuals: personalized N-of-1 trials. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(4):404-409. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kravitz RL, Duan, N, eds. Design and Implementation of N-of-1 Trials: A User’s Guide. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published February 2014. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/n-1-trials_research-2014-5.pdf

- 8.Eureka. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://info.eurekaplatform.org/

- 9.Spertus J, Dorian P, Bubien R, et al. Development and validation of the Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life (AFEQT) Questionnaire in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4(1):15-25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.958033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White IR, Turner RM, Karahalios A, Salanti G. A comparison of arm‐based and contrast‐based models for network meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2019;38(27):5197-5213. doi: 10.1002/sim.8360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373-498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung MK, Eckhardt LL, Chen LY, et al. ; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee and Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health . Lifestyle and risk factor modification for reduction of atrial fibrillation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(16):e750-e772. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin EJ, Al-Khatib SM, Desvigne-Nickens P, et al. Research priorities in the secondary prevention of atrial fibrillation: a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute virtual workshop report. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(16):e021566. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(4):427-436. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dukes JW, Dewland TA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Access to alcohol and heart disease among patients in hospital: observational cohort study using differences in alcohol sales laws. BMJ. 2016;353:i2714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitman IR, Agarwal V, Nah G, et al. Alcohol abuse and cardiac disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(1):13-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voskoboinik A, Kalman JM, De Silva A, et al. Alcohol abstinence in drinkers with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):20-28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus GM, Dukes JW, Vittinghoff E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous alcohol to assess changes in atrial electrophysiology. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7(5):662-670. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus GM, Vittinghoff E, Whitman IR, et al. Acute consumption of alcohol and discrete atrial fibrillation events. Ann Intern Med. 2021. doi: 10.7326/M21-0228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixit S, Stein PK, Dewland TA, et al. Consumption of caffeinated products and cardiac ectopy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(1):e002503. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EJ, Hoffmann TJ, Nah G, Vittinghoff E, Delling F, Marcus GM. Coffee consumption and incident tachyarrhythmias: reported behavior, mendelian randomization, and their interactions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(9):1185-1193. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Direito A, Carraça E, Rawstorn J, Whittaker R, Maddison R. mHealth technologies to influence physical activity and sedentary behaviors: behavior change techniques, systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):226-239. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9846-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson ED, Harrington RA. Evaluating health technology through pragmatic trials: novel approaches to generate high-quality evidence. JAMA. 2018;320(2):137-138. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shcherbina A, Hershman SG, Lazzeroni L, et al. The effect of digital physical activity interventions on daily step count: a randomised controlled crossover substudy of the MyHeart Counts Cardiovascular Health Study. Lancet Digit Health. 2019;1(7):e344-e352. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30129-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez MV, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, et al. ; Apple Heart Study Investigators . Large-scale assessment of a smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(20):1909-1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Y, Wang H, Zhang H, et al. ; MAFA II Investigators . Mobile photoplethysmographic technology to detect atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(19):2365-2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan.

eFigure 1. Overall Study Design and Workflow

eFigure 2. Example of Results Communicated to a Participant After Completion of their 6-Week N-of-1 Testing

eTable 1. Using answers to daily compliance questions during N-of-1 testing to inform per-protocol analyses

eTable 2. Specific customized triggers

eTable 3. Self-reported atrial fibrillation versus mobile ECG-detected atrial fibrillation during the primary study period (participant days)

eTable 4. Differences in daily AF episodes between N-of-1 and AF monitoring groups

eTable 5. Relative risks of self-reported AF during the last 4 weeks of the first 10-week treatment period comparing each individual trigger to the AF monitoring-only group

eTable 6. Differences in adverse events between N-of-1 and AF monitoring groups

eTable 7. Study participants contributing to trigger exposure versus avoidance meta-analyses from all study periods

eTable 8. Differences in Participant Characteristics by Trigger Selection

eTable 9. Trigger testing compliance by trigger type

eTable 10. Summary odds ratios for self-reported AF and AliveCor events for trigger exposure versus avoidance during the first N-of-1 trial period only

Data Sharing Statement.