Abstract

We present the application of Bayesian modeling to identify chemical tools and/or drug discovery entities pertinent to drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. The quinoline JSF-3151 was predicted by modeling and then empirically demonstrated to be active against in vitro cultured clinical methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant strains while also exhibiting efficacy in a mouse peritonitis model of methicillin-resistant S. aureus infection. We highlight the utility of an intrabacterial drug metabolism (IBDM) approach to probe the mechanism by which JSF-3151 is transformed within the bacteria. We also identify and then validate two mechanisms of resistance in S. aureus: one mechanism involves increased expression of a lipocalin protein and the other arises from the loss of function of an azoreductase. The computational and experimental approaches, discovery of an antibacterial agent, and elucidated resistance mechanisms collectively hold promise to advance our understanding of therapeutic regimens for drug-resistant S. aureus.

Keywords: naïve Bayesian modeling, Staphylococcus aureus, quinoline, intrabacterial drug metabolism, YceI, AzoR

Graphical Abstract

S. aureus is a coagulase, catalase, and Gram-positive cocci residing on the skin and anterior nares of about 30% of healthy individuals 1–2. Considered to be the most pathogenic of the Staphylococci, S. aureus is responsible for a multitude of human diseases, which are further complicated by its capability to cause infection by at least two primary mechanisms: direct tissue invasion and exotoxin production. Direct tissue invasion is the primary cause of pathogenesis in humans, of which skin and soft tissue infections, such as abscesses, have become the most common condition to be treated by physicians 3–4. Other significant diseases caused by S. aureus invasion of tissue include osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and pneumonia. Metastasis of any of these focal infections can lead to bacteremia and sepsis. On the other hand, toxin-mediated diseases caused by S. aureus include food poisoning, toxic shock syndrome, and scalded skin syndrome. Thus, S. aureus is a major cause of disease and burden for the population and for medical practitioners.

Traditionally, treatment for S. aureus infections has included β-lactams, such as penicillin G, nafcillin, and oxacillin 2, 5. This class of antibacterials targets transpeptidation (cross-linking) of peptidoglycan stem peptides. In 1959, methicillin – another antibiotic in this family – was licensed for use against S. aureus in England. A year later, reports of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) surfaced in Europe, and in 1968, the first hospital outbreak of MRSA in the United States was recognized 6. Resistance to methicillin is conferred by the mecA gene, which encodes PBP2a, a penicillin-binding protein with low affinity for β-lactams 7. During the period of 1987 to 2014, surveillance data have shown that S. aureus was a significant source of hospital-acquired infections, and nearly 50% of all hospital-acquired S. aureus infections were due to MRSA 5, 8–10. Nearly 20 years ago, treatment options for MRSA included vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 5. Unfortunately, therapeutic options for MRSA infections have changed little, and reports of vancomycin-intermediate resistant and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VISA and VRSA, respectively) make this notion more alarming 11–13. A thorough review by Kurosu et al. shows that the pipeline for agents against MRSA contains few options 14. Therapies such as dalbavancin, oritavancin, and tedizolid, though approved for use, are not utilized in the inpatient setting due to cost and lack of efficacy data for bacteremia and sepsis 15.

The majority of chemical space has yet to be explored for the seeds of new treatments for drug-resistant S. aureus infections. Herein, we present the application of a computational approach to advance drug discovery. Bayesian modeling, previously validated for use with data sets for the growth inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis 16–19 or Neisseria gonorrhoeae 20, is leveraged to discover and validate novel hit compounds against drug-resistant S. aureus. We demonstrate the successful prediction of in vitro growth inhibitory activity for quinoline JSF-3151, we proceed to show its value as a bactericidal agent against clinically relevant drug-resistant S. aureus strains with in vivo efficacy in a mouse model of infection, and we utilize genetic methods to identify and validate two mechanisms of resistance while probing their effects on JSF-3151 through intrabacterial drug metabolism (IBDM) 21–22.

RESULTS

Development of the Bayesian Model.

The PubChem Bioassay database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was queried with the keywords “aureus and MIC.” We ultimately selected the studies with the largest number of compounds tested against drug-resistant S. aureus to develop our training sets. Inspection of each data set was conducted to remove duplicates, choose the most conservative value of the MIC (minimum concentration of compound to inhibit bacterial growth in vitro by 90%), convert units from μM to μg/mL, and ensure that the strain being tested was drug-resistant. We found that the assays used S. aureus strains resistant to one or more of the following drugs: methicillin, linezolid, vancomycin, or fluoroquinolones. In total, our full training set (MRSA_1a) contained 1,633 compounds, of which 1,043 compounds (63.8%) were designated as active (MIC ≤ 10 μg/mL). This level of growth inhibition was deemed to be acceptable for a hit compound, based on our experience. The MRSA_1a training set encompassed a small yet fairly diverse portion of chemical space, which included known antibacterial scaffolds such as tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactams. However, it also included rhodanines, which are known to be promiscuous Pan Assay Interference compounds, or “PAINS” 23. Since our aim was to find a novel chemical entity with specificity against drug-resistant S. aureus, we hypothesized that removing (or pruning) these potentially problematic compounds as well as known antibacterial chemotypes from the training set would help teach the model to focus on new, high-quality chemical scaffolds. This type of structural pruning of the training set may be compared to our activity-based pruning utilized with models for mouse liver microsomal stability and Vero cell cytotoxicity 24–26. Additionally, a novel chemotype should have a heightened likelihood of operating via a novel mechanism of action. Utilizing this strategy, we manually pruned the active tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, rhodanines, other known PAINS, and β-lactams from the actives of MRSA_1a to produce a new training set (MRSA_1b) that contained 1,247 compounds, of which 657 compounds were classified as active (52.7%). These data sets were used as independent training sets to create two Bayesian models in Pipeline Pilot 9.1 (BIOVIA). We used the eight standard physiochemical descriptors plus the structural fingerprints FCFP6 (functional class fingerprints of maximum diameter 6, which utilize bits for different functional groups). For internal statistics obtained through five-fold internal cross-validation, MRSA_1a and MRSA_1b displayed Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) scores of 0.903 and 0.917, respectively. The sensitivity values were 93.5% and 96.5%, respectively, while the specificity metrics were 81.7% and 81.0%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The models were then assessed with an external test set of 374 in-house compounds (synthesized by the Freundlich laboratory and assayed versus MRSA ATCC 43300, of which 6.2% were active). A comparison was also included with a methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) model (Broad_MSSA), constructed with screening data extracted from ChemBank (http://chembank.broadinstitute.org) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The positive predictive value (Supplementary Table 2) demonstrated the order of performance to be: MRSA_1a > MRSA_1b >> Broad_MSSA (Supplementary Figure 1).

The MRSA_1a and MRSA_1b models were applied in a prospective virtual screen of a library of three million commercially available compounds from Enamine (http://www.enamine.net) accessed through the ZINC server (http://zinc.docking.org). For each compound in the library and each of the two MRSA models, a Bayesian score was calculated, such that the value scaled with the probability of the molecule being efficacious given our activity cutoff of 10 μg/mL. The top-scoring 15 candidates (10 from MRSA_1a and 5 from MRSA_1b) and bottom-scoring 8 candidates from MRSA_1b were assessed for in vitro growth inhibition activity. The MIC values against MRSA (heretofore referring to ATCC 43300 unless noted otherwise) and MSSA (heretofore referring to ATCC 25923 unless noted otherwise) strains were determined along with the Vero cell CC50 (minimum concentration of compound resulting in 50% growth inhibition of this model mammalian cell line) (Supplementary Table 3). Of the 15 top scoring compounds assayed, three of the five most active compounds exhibited an MIC ≤ 10 μg/mL versus the MRSA strain (Table 1). All three hits were from the MRSA_1b model. Interestingly, the highest scoring compound from MRSA_1a, the fluoroquinolone JSF-3144, displayed an MIC of 25 μg/mL (50 μM) against both MRSA and MSSA strains. JSF-3144 and JSF-3145 did not score within the range (11.7 – 15.3) for the top fifty compounds from the MRSA_1b model. The three MRSA_1b selected actives either scored just outside (JSF-3151, JSF-3157) of or within (JSF-3153) the range (7.06 – 9.95) for the top fifty compounds from the MRSA_1a model. Of the eight MRSA_1b bottom-scoring compounds in the Enamine library, all were inactive with an MIC > 50 μg/mL (Supplementary Table 4). As evidenced by our results with the bottom- and top-scoring compounds, the Bayesian models are able to enrich for active compounds while triaging inactives. Furthermore, as seen with our previous Bayesian models, the results also validate the utility of pruning 24–26.

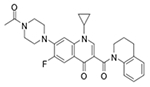

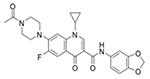

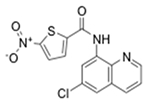

Table 1. Biological profiling of the most active compounds versus MRSA.

The MIC values are representative of three independent experiments. The model inherent in the selection of the molecule from the top-scoring fifty compounds is listed first in the Model/Score column.

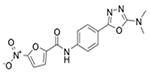

| Compound ID (JSF-#) | Chemical Structure | Model/Score | MRSA ATCC 43300 MIC In μg/mL (μM) | MSSA ATCC 25923 MIC in μg/mL (μM) | Vero cell CC50 in μg/mL (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z27692293 (3145) |

|

MRSA_1a/7.80 MRSA_1b/−17.7 |

12 (25) | 12 (25) | >50 (>100) |

| Z27646636 (3144) |

|

MRSA_1a/9.95 MRSA_1b/−12.6 |

25 (50) | 25 (50) | >50 (>100) |

| Z296972134 (3151) |

|

MRSA_1b/13.2 MRSA_1a/6.77 |

4.0 (12) | 1.6 (4.8) | >50 (>150) |

| Z1542057255 (3157) |

|

MRSA_1b/13.4 MRSA_1a/6.94 |

6.2 (18) | 6.2 (18) | 0.78 (2.0) |

| Z364195972 (3153) |

|

MRSA_1b/14.2 MRSA_1a/7.45 |

3.1 (10) | 6.2 (20) | 1.6 (5.0) |

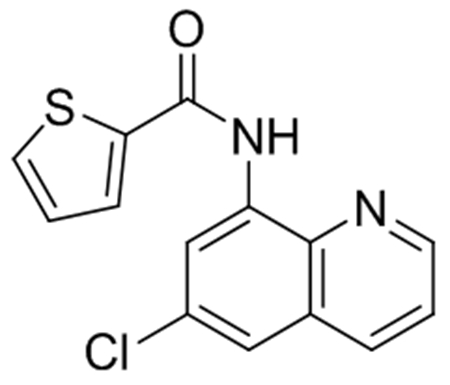

Quinoline JSF-3151 proved to be the most promising of the three hits based on its MIC values of 4.0 μg/mL (12 μM) and 1.6 μg/mL (4.8 μM) versus MRSA and MSSA strains, respectively, and its Vero cell CC50 value of >50 μg/mL (>150 μM). This gave JSF-3151 MRSA and MSSA selectivity indices (a ratio of mammalian cell cytotoxicity to antibacterial potency, SI = CC50/MIC) of >12 and >31, respectively. The other two hits, JSF-3153 and JSF-3157, failed to exhibit acceptable SI values (≥10) 27. Searches of the SciFinder (http://scifinder.cas.org), PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and ChEMBL databases (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl) supported the novelty of our finding of the antibacterial efficacy of JSF-3151. To further characterize the compound, we determined the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) against both MRSA and MSSA strains. The MBC values of 0.39 – 0.78 μg/mL (1.2 – 2.3 μM) versus MSSA and 1.6 – 3.1 μg/mL (4.8 – 9.3 μM) versus MRSA demonstrated the compound is capable of killing ≥2 log10 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL (Supplementary Figure 2). Furthermore, a time-kill curve showed that JSF-3151 at 1x MIC sterilized a MRSA culture within 4 h, more than six times faster than vancomycin at the same fold MIC (Supplementary Figure 2). Due to the increasing emergence of vancomycin resistance in the world 12–13, we also quantified the MIC of JSF-3151 against VISA and VRSA strains. Gratifyingly, we found that JSF-3151 exhibited even greater potency against six clinical isolates of VISA and five clinical isolates of VRSA, as compared to MRSA (Supplementary Table 5).

In vivo Study of JSF-3151 in a Mouse Peritonitis Model.

To support mouse efficacy studies, we quantified the mouse pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of JSF-3151, demonstrating an inability to reach the MIC over a 5 h time period (Supplementary Figure 3). This outcome is consistent with the compound’s poor kinetic aqueous solubility (S ≤ 0.060 μM) and low metabolic stability (half-life t1/2 of 1.46 min) in the presence of mouse liver microsomes. Given its poor solubility, JSF-3151 provided a suspension when formulated in sterile saline. JSF-3151 was dosed in BALB/c mice at 24 mg/kg – the highest achievable dose given its solubility – via the intraperitoneal route. Nevertheless, 2 out of 12 (16.7%) mice infected with the MRSA COL strain survived 3 d post-administration of a single dose of JSF-3151, as compared to 0/12 with the vehicle-only control and 12/12 with the 100 mg/kg subcutaneous dose of vancomycin (Supplementary Figure 3). This result, perhaps not surprising since the Bayesian model was only trained to predict in vitro efficacy and not aqueous solubility, mouse liver microsomal stability, and in vivo efficacy, suggests that analogs of JSF-3151 with optimized PK properties could demonstrate improved efficacy in this infection model.

Analysis of Drug Metabolism Demonstrates Intrabacterial Reduction of JSF-3151.

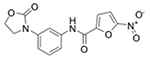

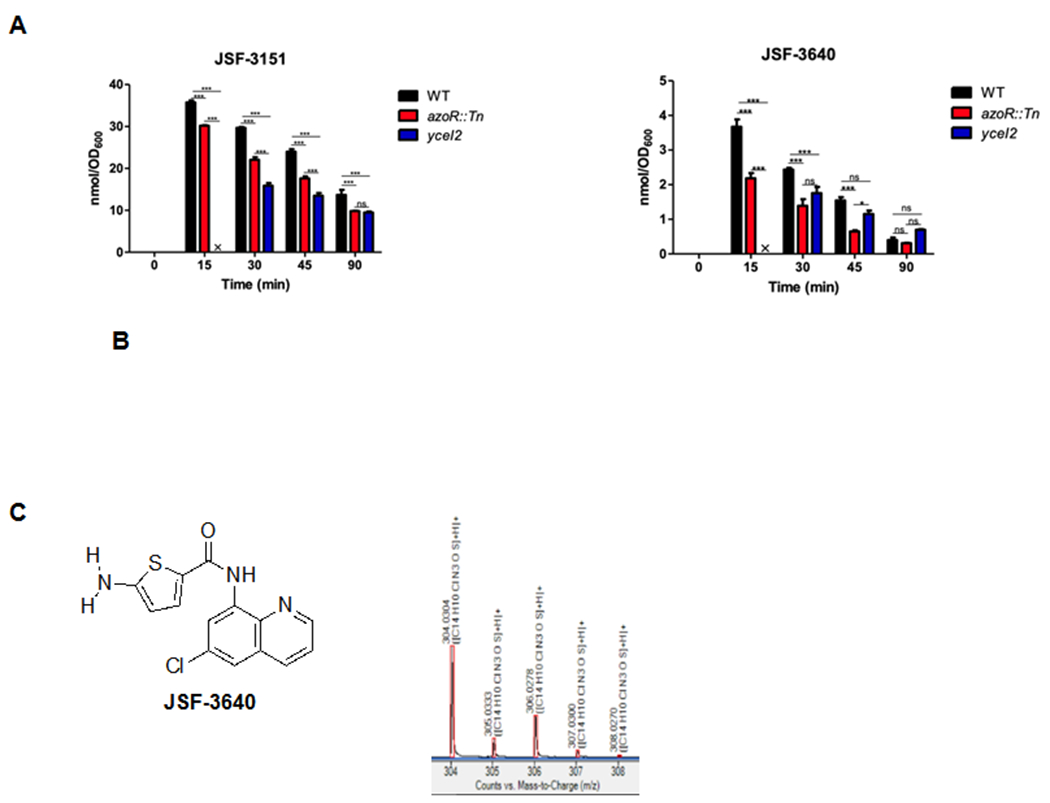

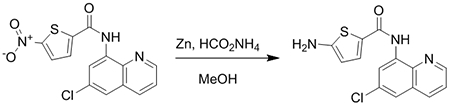

We next sought to probe the mechanism of action for JSF-3151 and began with the determination as to whether JSF-3151 accumulates within the bacterium using our recently developed approach to studying intrabacterial drug metabolism (IBDM) 21–22. Briefly, a MRSA WT strain (JMB1100; Table 2) was incubated with 10x MIC of JSF-3151 and was then sampled at 0, 15, 30, 45, and 90 min post-treatment. Following the quenching of metabolism and extraction of the cellular contents soluble in −80 °C 2:2:1 acetonitrile:methanol:water, analysis by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) showed a time-dependent accumulation of JSF-3151 within the bacterium (Figure 1A). We also noted a time-dependent increase of a new species labeled JSF-3640 (Figure 1B) whose high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) (Figure 1C) data were consistent with the corresponding amine metabolite of JSF-3151: 5-amino-N-(6-chloroquinolin-8-yl)thiophene-2-carboxamide. Critically, the synthetic metabolite co-eluted with the authentic metabolite on the LC (Supplementary Figure 4) and exhibited the same low-resolution and high-resolution mass spectrum profiles. Together these results support that JSF-3640 is, indeed, the amine metabolite of JSF-3151. The amine metabolite was whole-cell inactive (MIC > 50 μg/mL versus MRSA), despite the ability of JSF-3640 to accumulate within MRSA in a time-dependent fashion (Supplementary Figure 4).

Table 2. MIC profiling of JSF-3151 versus spontaneous resistant mutants.

The MIC values are representative of three independent experiments.

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Name | Strain Notes | JSF-3151 | Ampicillin | Doxycycline | Rifampicin |

| USA300_FPR3757 | Parent | 1.6 | >50 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

| JMB1100 | USA300_LAC cured of pUSA03 | 3.1 | >50 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

| USA300_FPR3757 yceI1 | T→G mutation at position −43 in yceI | >50 | >50 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

| USA300_FPR3757 yceI2 | adenosine base insertion at −37 in yceI | >50 | >50 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

| USA300_FPR3757 yceI3 | adenosine base deletion at position −41 in yceI | >50 | >50 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

| ATCC 43300 | MRSA | 3.1 | 32 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

| ATCC 25923 | MSSA | 3.1 | <0.25 | <0.25 | <0.25 |

Figure 1. IBDM studies of JSF-3151 and JSF-3640.

A) Time course study depicting the intrabacterial accumulation of JSF-3151 within S. aureus strains JMB1100 (WT), yceI2, and azoR::Tn that were treated with JSF-3151. B) Time course study depicting the intrabacterial accumulation of JSF-3640 within S. aureus strains JMB1100 (WT), yceI2, and azoR::Tn that were treated with JSF-3151. C) High-resolution mass spectrometry supports assignment of JSF-3640 as the amine metabolite, formed from JSF-3151, based on its spectral signature.

Membrane Depolarization and NO• Release are Ruled Out with regard to JSF-3151 Mechanism of Action.

Subsequently, we sought to rule out the potential for a non-specific mechanism of action such as membrane depolarization. MRSA was incubated with DiBAC4, bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)trimethine oxonol, which demonstrates increased fluorescence upon binding to proteins of a depolarized cell 28–29, and then treated with 4.5x MIC of JSF-3151. JSF-3151 failed to compromise the cell membrane, as compared to the positive control sodium deoxycholate (Supplementary Figure 5).

Given the propensity for nitroheterocycles to extrude nitric oxide (NO•) 30–32, we examined the ability of JSF-3151 to produce NO•. We assessed intrabacterial NO• release via the dye 4-amino-5-methylamino-2’,7’-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM diacetate) 33. In addition, the Griess reagent was used to detect the presence of nitrite in the supernatant, which is the oxidation product of NO• that undergoes efflux from the bacterium 34. Despite treatment of MRSA with 100 μM JSF-3151, neither DAF-FM (over 2 h) nor the Griess reagent (over 48 h) evidenced NO• production (Supplementary Figure 5), as compared to the DEA-NONOate positive control. Consistent with these experiments was our observation that the des-nitro JSF-3151 (N-(6-chloroquinolin-8-yl)thiophene-2-carboxamide; synthesized independently as JSF-3587) did not accumulate within the cell according to our above IBDM studies. The NO• detection assays and our IBDM platform suggest that the bactericidal efficacy of JSF-3151 is not attributed to NO• formation.

A Bacterial Lipocalin and an Azoreductase are Linked to Drug Resistance.

Using the MRSA strain LAC (Table 2), we used a genetic screen to select for resistant mutants using 8x MIC of JSF-3151. Single colonies were apparent following 3 d of incubation with a frequency of 6 x 10−8. In comparison, resistance frequencies for front-line agents such as vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, and linezolid at 8x their respective MIC value have been reported 13, 35–36 to range between 1 x 10−9 to 1 x 10−6. Ampicillin, erythromycin, doxycycline, rifampicin, and vancomycin exhibited the same MIC versus both JSF-3151–resistant strains and the parental strain. Whole-genome sequencing of three representative mutants, demonstrating >16-fold loss of susceptibility to JSF-3151, exhibited three distinct mutations in the promoter region of the gene SAUSA300_2620 (Table 2). Previously published reports suggested that SAUSA300_2620 gene product, annotated as a YceI-like protein, may have a similar function to the Burkholderia cenocepacia lipocalin (BcnA) which has been demonstrated to confer resistance to hydrophobic small molecules through their selective binding 37–38. Sanger sequencing of these representative mutants, labeled as yceI1, yceI2, and yceI3, further confirmed the presence of these mutations in the promoter region (Table 3). We hypothesized that the mutations in the promoter region led to an increase in production of YceI, which consequently affords resistance to JSF-3151.

Table 3. The effect of introducing the yceI alleles into S. aureus LAC.

The MIC values are representative of three independent experiments.

| Genotypea | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| pLL39 | 6.2 |

| pLL39_yceI | 6.2 |

| pLL39_yceI1 | 50 |

| pLL39_yceI2 | 50 |

| pLL39_yceI3 | 50 |

| yceI::Tn pLL39 | 0.78 |

| yceI::Tn pLL39_yceI | 1.6 |

| yceI::Tn pLL39_yceI1 | 50 |

| yceI::Tn pLL39_yceI2 | 50 |

| yceI::Tn pLL39_yceI3 | 50 |

All strains are isogenic and constructed in the LAC background.

To explore this hypothesis, our first goal was to observe the effect of each mutation with respect to JSF-3151 resistance. We cloned a PCR fragment containing −290 base pairs upstream of the predicted translational start site and yceI into a chromosomal integration vector (pLL39) 39. Five constructs were generated: empty vector, WT promoter+gene, and each of the three mutated promoter+gene sequences. Each of these plasmids was individually integrated into S. aureus strain RN4220 in the L54a attB locus 39–40. Integrates were verified using PCR (Supplementary Table 6). The individual integrated episomes were transduced into two different S. aureus strains: parental USA300_LAC (JMB1100) and an isogenic yceI::Tn mutant (JMB9587) (Supplementary Table 7) 41. The strains afforded two functional copies of yceI in strain JMB1100 and only one functional copy in the yceI::Tn strain. We next quantified the JSF-3151 MIC values for each of these strains (Table 3; Supplementary Figure 6). As expected, the strains containing any of the three yceI promoter mutations led to high level resistance to JSF-3151. In addition, the yceI::Tn mutant had a lower MIC than with JMB1100. A quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) study showed that relative to strain LAC, each of the three mutants had increased transcription of yceI (Supplementary Figure 6). Finally, we cloned a PCR fragment containing yceI into the pEPSA5 42. The pEPSA5_yceI vector contained yceI under the transcriptional control of a xylose-inducible promoter to enable gene over-expression. Following overnight induction with xylose, we witnessed a significant resistance to JSF-3151 (>64 fold) as compared to the strain carrying the empty vector (pEPSA5), as well as the no induction controls (Table 4). We hypothesized that increased expression of yceI would decrease the accumulation of JSF-3151 in cells. To test this hypothesis, IBDM analysis was performed with the yceI2 strain. Consistent with our hypothesis, treatment of the yceI2 strain with JSF-3151 resulted in a decreased rate of accumulation when compared to the parent strain. We also noted a decrease in the rate of JSF-3640 accumulation.

Table 4. The effect of overproducing yceI gene product on JSF-3151 resistance.

The MIC values are representative of three independent experiments.

| Strain ID | Growth with Xylose | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| LAC pEPSA5 | + | 0.78 |

| LAC pEPSA5_yceI | + | >50 |

| LAC pEPSA5 | − | 0.78 |

| LAC pEPSA5_yceI | − | 3.1 |

A second genetic screen was performed using the LAC yceI::Tn strain. Strains with heritable resistance to JSF-3151 arose at a frequency of approximately 3 x 10−8. Whole-genome sequencing found the four strains had single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in the gene SAUSA300_0206 (azoR). The mutations in azoR resulted in the following protein changes: Trp100stop (azoR1), Trp60stop (azoR2), Thr121Ile (azoR3), and Trp40stop (azoR4); respectively, they exhibited MIC shifts of 15-, 32-, 64-, and 25-fold as compared to the yceI::Tn parental strain (Table 5). For comparison, a LAC strain with a transposon insertion in azoR was constructed and demonstrated an increased MIC when compared to LAC (50 versus 1.5 μg/mL). Moreover, returning azoR to the mutant strains via the plasmid pCM28 decreased MIC values to the levels of the yceI::Tn strain (Table 6). Over-expression of azoR in LAC using the pEPSA5 vector increased sensitivity to JSF-3151 (Table 6). These data verify that the lack of AzoR increases JSF-3151 resistance.

Table 5. MIC profiling of JSF-3151 versus spontaneous resistant mutants in the background of the yceI::Tn mutant.

The MIC values are representative of three independent experiments.

| Genotypea | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| LAC | 1.5 |

| yceI::Tn | 0.78 |

| azoR::Tn | 50 |

| yceI::Tn azoR1 | 12 |

| yceI::Tn azoR2 | 25 |

| yceI::Tn azoR3 | >50 |

| yceI::Tn azoR4 | 25 |

All strains are isogenic and constructed in the LAC background.

Table 6. The effect of overproducing azoR gene product on resistance to JSF-3151.

The MIC values are representative of three independent experiments.

| Genotype | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| LAC pEPSA5a | 1.5 |

| LAC pEPSA5_azoR | 0.39 |

| yceI::Tn pCM28b | 0.78 |

| yceI::Tn pCM28_azoR | 0.78 |

| yceI::Tn azoR1 pCM28 | >50 |

| yceI::Tn azoR1 pCM28_azoR | 3.1 |

| yceI::Tn azoR2 pCM28 | 25 |

| yceI::Tn azoR2 pCM28_azoR | 1.5 |

| yceI::Tn azoR3 pCM28 | >50 |

| yceI::Tn azoR3 pCM28_azoR | 1.5 |

| yceI::Tn azoR4 pCM28 | 25 |

| yceI::Tn azoR4 pCM28_azoR | 1.5 |

Strains containing pEPSA vectors were cultured with 1% xylose.

All strains were constructed in the LAC background.

The azoR gene is predicted to encode for an intracellular FMN-dependent NADH-azoreductase, catalyzing reductive cleavage of azo groups. Azoreductases from E. coli 43–44, P. aeruginosa 45, B. wakoensis A01 46, and R. sphaeroides 47 have also been reported to reduce nitro groups. We hypothesized that this enzyme is responsible for the biotransformation of JSF-3151 to JSF-3640. To test this hypothesis IBDM analysis was performed with the azoR::Tn strain. Interestingly, the accumulation of both JSF-3151 and metabolite JSF-3640 were decreased in the azoR::Tn strain as compared to the WT strain (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 8). In comparison, the intrabacterial accumulation of JSF-3151 was further depressed in the yceI2 mutant (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 8). The relative level of accumulation of metabolite JSF-3640 was similar in the yceI and azoR mutants. With both mutants, the intrabacterial levels of both compounds did not reach those found in the WT strain until at least 45 min post-addition of JSF-3151 to the culture.

DISCUSSION

Antibacterial resistance is a serious threat to global public health, and its burden to healthcare increases every year. The diseases caused by S. aureus infection are no exception, as they are amongst the most commonly encountered cases in the clinic today. Growing resistance to the therapeutic options currently available, such as β-lactam resistance and vancomycin resistance, necessitates new antibacterial candidates. Thus, new approaches are required to afford novel drug discovery and tool compounds, especially with time- and cost-efficiency.

Here, our Bayesian modeling approach was shown to be successful in screening millions of compounds and at a fraction of the time traditional high throughput screening would take. The discovery of JSF-3151 via a machine learning approach validates the use of this strategy for identifying active compounds versus drug-resistant S. aureus, extending efforts from our labs with M. tuberculosis 16–19 and Neisseria gonorrhoeae 20 and joins one publication we note that specifically focused on drug-resistant S. aureus 48. This publication from Wang et al. disclosed machine learning models for the growth inhibition of MRSA that correctly predicted (1/56 = 1.8% hit rate) an active (MIC = 4 – 8 μg/mL) compound ((E)-2-isopropyl-5-styrylbenzene-1,3-diol) versus only MRSA and MSSA strains and did not mention critical downstream studies to assess in vivo efficacy and mechanism of action/resistance. Furthermore, our Bayesian models have significantly expanded beyond methicillin resistance to include clinically relevant data sets with strains resistant to linezolid, vancomycin, or fluoroquinolones.

Our Bayesian models were built with 46 data sets pertaining to assays against drug-resistant S. aureus. We utilized these assays in particular because they examined the highest number of compounds against drug-resistant S. aureus. These data sets were crucial in developing the “prior distribution,” or rather giving statistical weight to the chemical moieties and physiochemical properties relating to activity and inactivity. Our Bayesian models were successful in enriching for active and inactive small molecules. Through the use of the MRSA_1b model constructed from the pruned 26 training set, we were led to JSF-3151, a small molecule that possesses anti-Staphylococcal activity and a novel structure for an antibacterial.

Thus, we hypothesized that the unique structure of JSF-3151 could imply a new mechanism of antibacterial activity. While non-specific mechanisms of action were ruled out, the target remains elusive. The in vitro bactericidal activity of JSF-3151 implies that it modulates the activity of one or more targets that alone or together are essential for bacterial growth. Spontaneous resistant mutants were raised that increased transcription of yceI, encoding a bacterial lipocalin protein that proposedly binds JSF-3151 in analogy to the elegant studies of Valvano and colleagues with Burkholderia cenocepacia 37, 49. While their work involved complementation of the B. cenocepacia lipocalin knockout with S. aureus yceI, we are unaware of any reports in the literature detailing the role of YceI in S. aureus drug resistance. Our genetic studies have demonstrated that over-expression of yceI leads to loss of JSF-3151 in vitro activity. The analysis of IBDM data with the yceI2 mutant evidenced decreased intrabacterial exposure to both the parent JSF-3151 and identified metabolite JSF-3640 as compared to the WT strain. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that YceI is decreasing the rate of JSF-3151 entry into S. aureus cells. Future studies will be required to determine if YceI binds JSF-3151.

Raising JSF-3151 mutants in the yceI::Tn background afforded mutations in the gene azoR. Strains with null mutations in azoR had increased resistance to JSF-3151. We are unaware of previous reports of drug-resistant mutants in S. aureus occurring through mutations in an azoreductase despite elegant studies of the role of this protein family in biotransformations of nitroaromatic and azo small molecules 43–47, 50. It is possible that AzoR is involved in the transformation of JSF-3151 into a yet to be identified compound that has increased antibacterial activity against S. aureus. Alternatively, while JSF-3640 did not exhibit antibacterial activity despite its ability to enter cells, its formation from JSF-3151 as promoted by AzoR could be cidal. In support of the hypothesis, the azoR mutant had decreased intracellular accumulation of JSF-3640.

The drug resistance and IBDM results are supportive of decreased intrabacterial exposure to JSF-3151 correlating with reduced growth inhibition of S. aureus. Over-expression of yceI provides depressed accumulation of, and resistance to, JSF-3151. Loss-of-function mutations in azoR also decrease intrabacterial levels of JSF-3151 and increase resistance to JSF-3151. However, the degree of biotransformation of JSF-3151 to JSF-3640 as quantified by IBDM in these strains and in the WT does not appear to be linked to growth inhibition. JSF-3640 is a whole-cell inactive metabolite that appears to be formed by a pathway largely independent of the activity of AzoR. The AzoR-dependent biotransformation product of JSF-3151 has yet to be identified and may be linked to the mechanism of action of JSF-3151.

It is noteworthy that reports of S. aureus metabolomics appear to primarily focus on the effect of antibacterials on bacterial metabolite pools 50–55, and not on intracellular drug metabolism. In vitro enzyme assays have been leveraged as a major approach to study enzyme-mediated small molecule modifications 56–57, but are potentially limited by a lack of physiological relevance to intrabacterial metabolism. We are aware of one elegant report that utilized LC-MS to quantify drug accumulation in S. aureus, but it is noteworthy that drug metabolism was not considered 58. Increased emphasis on the application of IBDM to S. aureus programs should further enlighten our understanding of bacterial metabolic pathways, and especially those engaged in xenobiotic biotransformations, while also providing information critical to the design of more potent analogs of JSF-3151 and, thus, furthering the impact of antibacterial machine learning models.

CONCLUSIONS

The results presented herein disclose an antibacterial agent JSF-3151 with both in vitro and in vivo efficacy against clinically relevant drug-resistant S. aureus strains. This molecule was discovered by the successful application of a Bayesian modeling approach. The mechanism of resistance to JSF-3151 has been shown to involve 1) over-expression of the lipocalin-like protein YceI or 2) the loss of function of the azoreductase AzoR. To the best of our knowledge, neither of these resistance mechanisms has been described for staphylococci and both are supported by extensive genetic analyses. Furthermore, we have demonstrated how each type of mutation perturbs accumulation of JSF-3151 and its identified metabolite JSF-3640 within the bacterium. The chemical entity, knowledge of resistance mechanisms, and platforms of Bayesian modeling and intrabacterial drug metabolism should inform further efforts to impact next-generation therapeutic strategies for drug-resistant S. aureus infections.

METHODS

In the detailed methods below, no unexpected or unusually high safety hazards were encountered.

Materials and Services.

Quick ligase, Phusion polymerase, and restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Gel purification kits were purchased from Qiagen. Tryptic Soy broth (TSB) was purchased from MP Biomedicals. Mueller-Hinton broth and agar were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Whole-genome sequencing was conducted by the Genomics Center, Rutgers University-New Jersey Medical School, while Sanger sequencing was performed at Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ.

Mice.

All animal experiments were approved by the Rutgers Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments used 6-week old female outbred CD-1 or Swiss Webster mice (Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA). Mice were housed in filter-top cages and maintained in accordance with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Care criteria.

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, primers, and plasmids.

MRSA (43300) and MSSA (25923) strains used in this study were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). VRSA and VISA strains were obtained from the Kreiswirth laboratory at the Public Health Research Institute Center (Newark, NJ). Other S. aureus strains used in this study were derivatives of the S. aureus strain LAC, which is a community acquired MRSA strain. JMB1100 is a derivative of LAC that has been cured of the pUSA03, which confers multidrug resistance 59. S. aureus were routinely cultured in solid or liquid tryptic soy broth. For experiments, S. aureus were cultured in 5 mL Mueller Hinton and grown at 37°C in 30 mL capacity culture tubes with shaking at 200 rpm. Overnight cultures were diluted 1/1000 and transferred into 96 well plates containing serial dilutions of JSF-3151 in Mueller-Hinton broth. Final concentrations were calculated based on 200 μL final volume. Plates were wrapped with parafilm from the sides to prevent dehydration and incubated statically at 37 °C. Results were measured after 18 h of incubation. When selecting for plasmids, transposon, or episome insertions, antibiotics were added at the final following concentrations: 150 μg/mL ampicillin; 30 μg/mL chloramphenicol (Cm); 10 μg/mL erythromycin (Erm); 3 μg/mL tetracycline (Tet). For routine plasmid maintenance, media were supplemented with 10 μg/mL or 3.3 μg/mL of chloramphenicol.

Data Collection and Curation.

The PubChem Bioassay Database was queried with the phrase “aureus and MIC” which yielded 22,619 for results. After sorting the largest sets with S. aureus results, the strain in each assay was identified and sorted into “drug-resistant,” “drug-sensitive,” and “unknown.” In total, 139 assay results were collected. For each of these assays, the structural data files (SDF) and comma-separated value (CSV) files were downloaded. The SDF’s contained every tested compound’s PubChem CID and 2D structural information (but no assay results). The CSV files contained every tested compound’s CID and assay results (but no structures). Additionally, for every AID the corresponding paper was retrieved. Every assay result from a CSV file was inspected and compared to its relevant paper. Using this quality control process, any erroneous data could be noted or discarded from our study. Following the comprehensive manual inspection process, we found 72 data sets pertaining to drug-sensitive S. aureus, 46 data sets pertaining to drug-resistant S. aureus, and 21 data sets that were classified as unknown. The drug-resistant sets contained assay results primarily for MRSA but also included assay results against fluoroquinolone-resistant or linezolid-resistant S. aureus, as well. Unfortunately, one of the CSV files from the drug-resistant set, AID 548647, had erroneous data and was, therefore, discarded. The data within the CSV files and SDF’s for each of the drug-resistant sets were collated into a spreadsheet in Discovery Studio 4.0 (BIOVIA, Inc., San Diego, CA). For consistency, the μM sets were converted to μg/mL. We then deleted duplicate compounds using a custom script in Pipeline Pilot 9.1 (BIOVIA, Inc., San Diego, CA) and compounds with a molecular weight > 850 g/mol.

Training and Test Sets.

In total, our full training set from PubChem contained 1,633 compounds, of which 1,043 compounds (63.8%) were designated as active (MIC ≤ 10 μg/mL). This full training set (MRSA_1a) encompassed a small yet fairly diverse portion of chemical space, which included known antibacterial scaffolds such as tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactams. However, it also included rhodanines (which are known to be promiscuous Pan Assay Interference compounds, called “PAINS” 23, 60). We hypothesized that removing (or pruning) these problematic compounds as well as known antibacterial chemotypes from the training set would help teach the Bayesian to further focus on new chemical scaffolds, which should increase the likelihood that they display novel mechanisms of action 26. It is important to note, however, that our M. tuberculosis Bayesian models have routinely found hits which differ significantly from the model testing set (pairwise Tanimoto similarity < 0.7). Utilizing this strategy, we manually pruned the tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, rhodanines, and β-lactams from the actives subset of MRSA_1a to produce a new training set (MRSA_1b) that contained 1,247 compounds, of which 657 compounds were classified as active (52.7%).

Another training set that we used as a reference was based on the Broad Institute’s assay results against methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (Broad_MSSA). This training set has 10,934 compounds, of which 193 compounds (1.77%) were defined as “active” according to the Z-factor threshold selected by the researchers at the Broad Institute (Tali Mazor, assay names: ChemBank BacTiterGlo 1064.0004 and 1064.0005; http://chembank.broadinstitute.org). These 193 actives also included known antibacterials, such as levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, β-lactams, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones.

These datasets were used as independent training sets to create two different, new drug-resistant S. aureus machine learning models and the reference MSSA model in Pipeline Pilot 9.1. These Bayesian models utilized nine different descriptors: AlogP, molecular weight, number of rings, number of aromatic rings, number of rotatable bonds, number of hydrogen bond donors, number of hydrogen bond acceptors, molecular fractional polar surface area, and molecular function class fingerprints of maximum diameter 6 (FCFP_6, characterizing the 2D substructures up to and including 6 rings/zones/dimensions of topology) 61–62. Together, these descriptors define the physiochemical properties of each compound as a whole and the 2D substructures of different regions within it. These descriptors were then combined in different ways, with different weights applied to the sets of different descriptor combinations, until the most accurate model was produced, according to five-fold internal cross-validation.

The top 100 scoring compounds from MRSA_1a and the top 50 from MRSA_1b versus an Enamine (www.enamine.net) library of 3 million compounds, accessed through Zinc (http://zinc.docking.org), were then visually inspected to identify and discard any reactive compounds or promiscuous inhibitors (e.g., Michael acceptors, rhodanines, etc.). Also removed were compounds that were visually deemed too similar to the training set to be novel (e.g., tetracyclines or almost all fluoroquinolones), or compounds with chemotypes that were not of general interest (i.e., peptides or fatty acids) 23, 60. 49 of the top 50 compounds from MRSA_1a did not pass inspection. Therefore, we also inspected the next 50 top scoring compounds from this model. Unsurprisingly, the highest-ranking compound from MRSA_1a was a fluoroquinolone which, instead of dismissing, we included in this model’s predictions to be experimentally validated. We selected an additional top 9 compounds from MRSA_1a, as well as the top 5 ranking compounds from MRSA_1b that passed inspection. All candidate compounds were purchased and assessed by LC/MS for ≥ 95% purity and the expected parent ion in the mass spectrum.

Drug Susceptibility Assays.

MICs were performed in 96-well microtiter plates. A DMSO stock solution of each compound was added to the first column and serially diluted across the columns of the plate. The last column of the plate contained no drug and served as a no-drug control. Overnight cultures of the bacterium being tested (MRSA ATCC 43300, MSSA ATCC 25923, or the aforementioned VRSA/VISA strains) were diluted 1000 fold (2 x 103 cells) and 100 μL was used as an inoculum in each well. MICs were determined by visual inspection for a pellet after 18 h incubation at 37 °C. Compounds were tested for cytotoxicity against Vero cells using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution kit (Promega). Vero cells were seeded in 96 well plates at a density of 2x104 cells per well and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C to allow attachments of the Vero cells. Compounds were then added to the wells starting from a final concentration of 50 μg/mL and making twelve 1:2 dilutions. Cells were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C. Then 20 μL of freshly prepared MTS:PMS reagents were added to each well. The plates were incubated for 2 h and then read at an absorbance of 490 nm.

Mouse Pharmacokinetic Study.

Animals and ethics assurance: Animal studies were carried out in accordance with the guide for the care and use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health, with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark. All animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and fed water and chow ad libitum, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering or discomfort. Two female CD-1 mice received a single dose of experimental compound administered orally at 25 mg/kg in 20% DMA/80% PEG300, and blood samples were collected in K2EDTA coated tubes pre-dose, 0.5, 1, 3 and 5 h post-dose. Blood was kept on ice and centrifuged to recover plasma, which was stored at −80 °C until analyzed by HPLC coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

LC/MS-MS analytical methods:

LC/MS-MS quantitative analysis for all molecules was performed on a Sciex Applied Biosystems Qtrap 4000 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled to an Agilent 1260 HPLC system, and chromatography was performed on an Agilent Zorbax SB-C8 column (2.1x30 mm; particle size, 3.5 μm) using a reverse phase gradient elution. Milli-Q deionized water with 0.1% formic acid (A) was used for the aqueous mobile phase and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) for the organic mobile phase. The gradient was: 5-90% B over 2 min, 1 min at 90% B, followed by an immediate drop to 5% B and 1 min at 5% B. Multiple-reaction monitoring of parent/daughter transitions in electrospray positive-ionization mode was used to quantify all molecules. Sample analysis was accepted if the concentrations of the quality control samples and standards were within 20% of the nominal concentration. Data processing was performed using Analyst software (version 1.6.2; Applied Biosystems Sciex). Neat 1 mg/mL DMSO stocks for all compounds were first serial diluted in 50/50 acetonitrile/water and subsequently serial diluted in drug free CD-1 mouse plasma (K2EDTA, Bioreclamation IVT, NY) to create standard curves (linear regression with 1/x^2 weighting) and quality control (QC) spiking solutions. 20 μL of standards, QCs, control plasma, and study samples were extracted by adding 200 μL of acetonitrile/methanol 50/50 protein precipitation solvent containing the internal standard (10 ng/mL verapamil). Extracts were vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. 100 μL of supernatant was transferred for HPLC-MS/MS analysis and diluted with 100 μL of Milli-Q deionized water.

Mouse Peritonitis-Sepsis Model.

MRSA COL strain was grown overnight in Mueller-Hinton media at 37 °C. The resulting culture was diluted in 5% hog mucin and 0.9% NaCl to a challenge inoculum of approximately 1.0 x 108 CFU per mouse. The challenge inoculum was confirmed by mannitol salt agar plate spreads and administered to female outbred Swiss Webster mice (Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA) via intraperitoneal injection (0.5 mL). Groups consisting of 12 mice were given single doses of vehicle (10% DMSO in sterile saline), JSF-3151 (24 mg/kg) or vancomycin (100 mg/kg) 1 h post-infection. Vehicle and JSF-3151 were administered via intraperitoneal injection while vancomycin was administered by subcutaneous injection (final injection volume = 0.2 mL). Mice were maintained in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of the Laboratory Care criteria. All surviving animals were humanely euthanized at the end of the study (3 d) by following the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. The animal study was approved by Rutgers Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

IBDM Studies.

A single colony of S. aureus strain was inoculated in fresh Mueller-Hinton media and grown overnight at 37 °C. The resulting overnight was diluted 1:100 in fresh Mueller-Hinton media, and 120 mL of the culture was grown in a 250 mL flask until OD600 was ~0.5. Then, JSF-3151 or JSF-3640 was added at the appropriate concentration and 10 mL of the culture were sampled at the relevant time intervals post-treatment. Each aliquot was centrifuged. The supernatant fraction was immediately stored while the pellet fraction was washed once with PBS and then resuspended in ice cold 2:2:1 acetonitrile:methanol:water to halt bacterial metabolism, and immediately placed on dry ice. The cells in the pellet fraction were subjected to bead beating and all of the fractions (6 pellet, 6 supernatant) were filtered (0.22 μm membrane) and analyzed by LC-MS. LC-MS was performed on an Agilent 1260 HPLC coupled to an Agilent 6120 MS. The run condition for the LC-MS was 10 – 100% acetonitrile in water over 10 min (both acetonitrile and water contained 0.1% formic acid). The column used for the run was an EMD Millipore Chromolith Speedrod RP18-e, 50 x 4.6 mm.

Membrane Depolarization Assay.

A single colony of S. aureus (ATCC 43300) was inoculated in fresh Mueller-Hinton media and grown to an OD600 of 0.5. DiBAC4 (bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)trimethine oxonol) was added to the resulting culture to afford a final concentration of 20 μg/mL and incubated for 5 min. All reads were performed in triplicate on a Biotek Synergy Neo 2 plate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 490 and 510 nm, respectively. In a Costar 96 well, black side, clear bottom plate, 200 μL of bacteria and dye were added and kept as a negative control. At a separate location of the plate 200 μL of bacteria and dye were added along with 4.5x MIC of JSF-3151 (~18 μg/mL, 54 μM). At yet another location, 200 μL of bacteria and dye were added along with sodium deoxycholate, the positive control, to a final concentration of 0.05% w/v. Reads were performed for 10 min with 5 s intervals.

Nitric Oxide Release Assays.

A) DAF-FM: A single colony of S. aureus (ATCC 43300) was inoculated in fresh Mueller-Hinton media to an OD600 of 0.2. DAF-FM diacetate (4-amino-5-methylamino-2’,7’-difluorofluorescein diacetate) was added to a final concentration of 10 μM and allowed to incubate for 30 min in the dark. All reads were performed in triplicate on a Biotek Synergy Neo 2 plate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 495 and 515 nm, respectively. In the first row of a Costar 96 well, black side, clear bottom plate, 200 μL of Mueller-Hinton media alone was added and kept as a negative control. In the second row, 200 μL of bacteria alone were added and also kept as a negative control. In the third row, bacteria treated with DAF-FM were added. In the fourth row, bacteria treated with DAF-FM and JSF-3151 (~33 μg/mL, 100 μM) for 120 min were added. In the fifth row, bacteria treated with DAF-FM and 100 μM diethylamine NONOate diethylammonium salt (DEA-NONOate) for 120 min were added. B) Griess: Sodium nitrite stock solutions ranging from 50 – 0.78 μM (2-fold dilutions) were prepared in Mueller-Hinton media. A single colony of S. aureus (ATCC 43300) was inoculated in fresh Mueller-Hinton media and grown to an OD600 of 0.4. The resulting culture was split into 3 equal volume batches. The first batch served as the negative control, the second volume was treated with JSF-3151 (~33 μg/mL, 100 μM), and the third volume was treated with DEA-NONOate (100 μM). Following incubations of 24 h and 48 h, 1 mL of culture was sampled and centrifuged. The supernatant was placed in the same plate as mentioned above along with the nitrite standards (180 μL per well). To each of these wells, 20 μL of freshly prepared Griess reagent mix was added, and the plate was allowed to sit at room temperature for 30 min. The plate was read with the above reader at an absorbance of 548 nm. Reads from the sodium nitrite standards were used to correlate absorbance to concentration, which facilitated estimation of nitrite production.

Molecular Biology.

Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a cloning host throughout. Plasmids were passaged through RN4220 and subsequently transduced into the appropriate strains using bacteriophage 80α 63–64. The amplicons used to create the pll39_yceI vectors were: 2620upBamHI and 2620downSalI. The pLL39 vector was linearized with Sall and BamHI and combined with similarly digested PCR fragments. The pLL39_yceI constructs were transformed into RN4220 containing pLL2787 and integrated onto the chromosome at the L54a attB site as previously described 39. Episome integration was verified using the Scv8 and Scv9 primers 39. The integrated pLL39_yceI constructs were transduced individually from RN4220 into JMB1100. The yceI::Tn and azoR::Tn alleles were acquired from the NARSA collection 41 and was transduced into JMB1100 before further strain construction. LAC genomic DNA was used as a template and the following primer pairs were used to create amplicons for cloning: 2620uppEPBamHI and 2620downSalI; pEPSA5-0206 EcoRI for and pEPSA5-0206 BamHIrev; pCM28-0206 BamHI rev and pCM28-0206 PstI for (S6 Table). The pEPSA5 and pCM28 vectors were linearized with restriction enzymes and combined with similarly digested PCR fragments before ligation. Sanger sequencing was used to confirm vectors (Genewiz; South Plainfield, NJ). Single nucleotide polymorphisms were mapped as previously described 65.

Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR).

The S. aureus strains, wild type and three JSF-3151–spontaneous resistant mutants, were grown to mid-log phase (OD595 = 0.4). Bacteria were harvested and the pellets were lysed, post TRIzol™ (Invitrogen) addition, by bead beating. The total RNAs were extracted in chloroform and purified via RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). The cDNA library was constructed via reverse transcription using 2 μg total RNA as template with SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). The expressions of yceI and 16S rRNA were measured by qPCR via SuperScript III Platinum SYBR Green One-Step qPCR Kit with Rox (Invitrogen).

Compound Synthesis.

Reagents and solvents for synthesis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific, or Enamine Ltd., and used without further purification unless noted otherwise. Analytical TLC was performed with Merck silica gel 60 F254 plates. Silica gel column chromatography was conducted with Teledyne Isco CombiFlash Companion or Rf+ systems. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance III HD 500 MHz instrument and are listed in parts per million downfield from tetramethylsilane. LC-MS was performed on an Agilent 1260 HPLC coupled to an Agilent 6120 MS. All synthesized compounds were at least 95% pure as judged by their HPLC trace at 220 or 250 nm and were characterized by the expected parent ion(s) in the MS trace. HRMS data were acquired on an Agilent 6220 Accurate-Mass Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer.

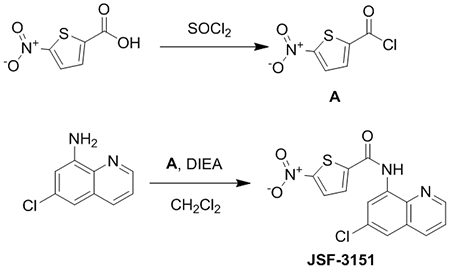

General Procedure A: Synthesis of JSF-3151

JSF-3151 was prepared in two steps. In short, a round-bottom flask was charged with 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (1.00 g, 5.78 mmol). Thionyl chloride (10 mL) was then added with stirring. After 3 h, the product A was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a light yellow solid (88% yield). 6-chloroquinolin-8-amine (1.03 g, 5.78 mmol) was added in a round-bottom flask followed by the addition of 15 mL dichloromethane. A (0.971 g, 5.09 mmol) was then added followed by diisopropylethylamine (1.20 equiv, 6.94 mmol, 1.21 mL). The mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for about 6 h. The reaction mixture was washed twice with water and saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution and once with saturated aqueous brine solution. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and then filtered through a pad of Celite. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the product was purified by flash column chromatography (10% methanol:dichloromethane) to afford the product as a yellow solid (1.67 g, 87% yield): 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO, 500 MHz) δ 10.9 (s, 1H), 9.06 – 9.00 (m, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.79 – 7.73 (m, 1H). Also noted 5.8 (s, DCM), 1.2 (m). 13C NMR ((CD3)2SO, 126 MHz) δ 158.8, 154.3, 150.4, 145.2, 137.9, 136.6, 135.1, 131.4, 130.7, 129.4, 129.1, 124.0, 122.8, 119.5. HRMS (ESI): Calculated for C14H8ClN3O3S (M+H)+ = 334.0053; Observed 334.0069 (+4.8 ppm).

Compound 3 – JSF-3587

JSF-3587 was synthesized following General Procedure A on a 0.3 mmol scale. Following flash chromatography, the product was isolated as a white solid (82 mg, 95% yield): 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO, 500 MHz) δ 10.6 (s, 1H), 9.01 (dd, J = 4.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (d, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (t, J = 4.7, 3.9 Hz, 1H). Also noted 5.7 (s, DCM), 3.3 (s, H2O). LRMS (ESI): Calculated for C14H9ClN2OS (M+H)+ = 289.0; Observed 289.0.

General Procedure B: Synthesis of JSF-3640

JSF-3151 (10 mg, 0.030 mmol) was added to a 20 mL scintillation vial. This was followed by the addition of Zn powder (9.7 mg, 0.15 mmol), ammonium formate (9.5 mg, 0.15 mmol), and 5 mL of methanol. The reaction was allowed to stir for 1 h at room temperature. Workup and purification was performed as outlined by General Procedure A. The reaction mixture was washed twice with water and saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution and once with saturated aqueous brine solution. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and then filtered through a pad of Celite. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the product was purified by flash column chromatography (10% methanol:dichloromethane) to afford the product.

JSF-3640 was synthesized following General Procedure B. Following flash chromatography, the product was isolated as an off-white solid (8.1 mg, 88% yield): 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO, 500 MHz) δ 10.1 (s, 1H), 8.96 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 8.59 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (s, 2H), 5.99 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H). Also noted 5.7 (s, DCM), 3.3 (s, H2O), 1.2 (s). HRMS (ESI): Calculated for C14H10ClN3OS (M+H)+ = 304.0311; Observed 304.0304 (−2.3 ppm).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported at Rutgers University – New Jersey Medical School by the US National Institutes of Health grants U19AI109713 (J.S.F.) and T32AI125185 (J.S.P.). The Boyd lab was supported by NIAID grant R01AI139100-01. We thank Professor Barry Kreiswirth (Rutgers/PHRI) for providing the VISA and VRSA strains. Dr. John Eng (Princeton University) is thanked for guidance with the HRMS studies.

Abbreviations

- IBDM

intrabacterial drug metabolism

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant S. aureus

- VISA

vancomycin-intermediate resistant S. aureus

- VRSA

vancomycin-resistant S. aureus

- MIC

minimum concentration of compound to inhibit bacterial growth in vitro by 90%

- PAINS

Pan Assay Interference compounds

- FCFP6

functional class fingerprints of maximum diameter 6

- ROC

Receiver Operator Characteristic

- MSSA

methicillin-sensitive S. aureus

- CC50

minimum concentration of compound resulting in 50% growth inhibition of this model mammalian cell line

- MBC

minimum bactericidal concentration

- CFU

colony-forming units

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- HRMS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- DiBAC4

bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)trimethine oxonol

- DAF-FM

4-amino-5-methylamino-2’,7’-difluorofluorescein

- qPCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism/s

Footnotes

Comparative model external ROC curves; In vitro bactericidal activity of JSF-3151; In vivo profiling of JSF-3151; IBDM studies of JSF-3151 and its metabolite JSF-3640; JSF-3151 membrane depolarization and NO• release assays; Quantification of yceI transcription in JSF-3151 resistant strains; Internal Statistics for Bayesian Models; External Statistics for Bayesian Models; S. aureus MIC values for top-scoring compounds from MRSA_1a and MRSA_1b predictions with the Enamine library; MRSA MIC values for bottom-scoring compounds from MRSA_1b predictions with the Enamine library; MIC of JSF-3151 versus VRSA and VISA strains; Primers used in this study; Strains and plasmids used in this study; Accumulation metrics for JSF-3151 and JSF-3640 in select strains.

Competing Interests

S.E. is the CEO of Collaborations Pharmaceuticals that is exploring the use of machine learning techniques to discover, optimize, and commercialize novel anti-infective agents.

References

- 1.Wertheim HF; Melles DC; Vos MC; van Leeuwen W; van Belkum A; Verbrugh HA; Nouwen JL, The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet. Infect. Dis 2005, 5, 751–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong SY; Davis JS; Eichenberger E; Holland TL; Fowler VG Jr., Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2015, 28, 603–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran GJ; Krishnadasan A; Gorwitz RJ; Fosheim GE; McDougal LK; Carey RB; Talan DA; Group, E. M. I. N. S., Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N. Engl. J. Med 2006, 355, 666–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talan DA; Singer AJ, Management of skin abscesses. N. Engl. J. Med 2014, 370, 2245–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowy FD, Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med 1998, 339, 520–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett FF; McGehee RF Jr.; Finland M, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at Boston City Hospital. Bacteriologic and epidemiologic observations. N. Engl. J. Med 1968, 279, 441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuhashi M; Song MD; Ishino F; Wachi M; Doi M; Inoue M; Ubukata K; Yamashita N; Konno M, Molecular cloning of the gene of a penicillin-binding protein supposed to cause high resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol 1986, 167, 975–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance, S., National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am. J. Infect. Control 2004, 32 (8), 470–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hidron AI; Edwards JR; Patel J; Horan TC; Sievert DM; Pollock DA; Fridkin SK; National Healthcare Safety Network, T.; Participating National Healthcare Safety Network, F., NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 2008, 29, 996–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner LM; Webb AK; Limbago B; Dudeck MA; Patel J; Kallen AJ; Edwards JR; Sievert DM, Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens Associated With Healthcare-Associated Infections: Summary of Data Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011-2014. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 2016, 37, 1288–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howden BP, Recognition and management of infections caused by vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heterogenous VISA (hVISA). Intern. Med. J 2005, 35 Suppl 2, S136–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC, Update: Staphylococcus aureus with Reduced Susceptibility to Vancomycin -- United States, 1997. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 1997, 46, 813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramatsu K; Aritaka N; Hanaki H; Kawasaki S; Hosoda Y; Hori S; Fukuchi Y; Kobayashi I, Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 1997, 350, 1670–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurosu M; Siricilla S; Mitachi K, Advances in MRSA drug discovery: where are we and where do we need to be? Expert Opin. Drug Discov 2013, 8, 1095–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. https://www.uptodate.com.

- 16.Ekins S; Perryman AL; Clark AM; Reynolds RC; Freundlich JS, Machine Learning Model Analysis and Data Visualization with Small Molecules Tested in a Mouse Model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection (2014-2015). J. Chem. Inf. Model 2016, 56, 1332–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekins S; Freundlich JS, Computational models for tuberculosis drug discovery. Methods Mol. Biol 2013, 993, 245–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekins S; Freundlich JS, Validating new tuberculosis computational models with public whole cell screening aerobic activity datasets. Pharm. Res 2011, 28, 1859–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekins S; Reynolds RC; Kim H; Koo MS; Ekonomidis M; Talaue M; Paget SD; Woolhiser LK; Lenaerts AJ; Bunin BA; Connell N; Freundlich JS, Bayesian models leveraging bioactivity and cytotoxicity information for drug discovery. Chem. Biol 2013, 20, 370–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira JC; Daher SS; Zorn KM; Sherwood M; Russo R; Perryman AL; Wang X; Freundlich MJ; Ekins S; Freundlich JS, Machine Learning Platform to Discover Novel Growth Inhibitors of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Pharm. Res 2020, 37, 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X; Inoyama D; Russo R; Li SG; Jadhav R; Stratton TP; Mittal N; Bilotta JA; Singleton E; Kim T; Paget SD; Pottorf RS; Ahn YM; Davila-Pagan A; Kandasamy S; Grady C; Hussain S; Soteropoulos P; Zimmerman MD; Ho HP; Park S; Dartois V; Ekins S; Connell N; Kumar P; Freundlich JS, Antitubercular Triazines: Optimization and Intrabacterial Metabolism. Cell Chem. Biol 2020, 27, 172–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X; Perryman AL; Li SG; Paget SD; Stratton TP; Lemenze A; Olson AJ; Ekins S; Kumar P; Freundlich JS, Intrabacterial Metabolism Obscures the Successful Prediction of an InhA Inhibitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis 2019, 5, 2148–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendgen T; Steuer C; Klein CD, Privileged scaffolds or promiscuous binders: a comparative study on rhodanines and related heterocycles in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem 2012, 55, 743–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perryman AL; Patel JS; Russo R; Singleton E; Connell N; Ekins S; Freundlich JS, Naive Bayesian Models for Vero Cell Cytotoxicity. Pharm. Res 2018, 35, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stratton TP; Perryman AL; Vilcheze C; Russo R; Li SG; Patel JS; Singleton E; Ekins S; Connell N; Jacobs WR Jr.; Freundlich JS, Addressing the Metabolic Stability of Antituberculars through Machine Learning. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 8, 1099–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perryman AL; Stratton TP; Ekins S; Freundlich JS, Predicting Mouse Liver Microsomal Stability with “Pruned” Machine Learning Models and Public Data. Pharm. Res 2016, 33, 433–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoyama D; Paget SD; Russo R; Kandasamy S; Kumar P; Singleton E; Occi J; Tuckman M; Zimmerman MD; Ho HP; Perryman AL; Dartois V; Connell N; Freundlich JS, Novel Pyrimidines as Antitubercular Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e02063–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suller MT; Lloyd D, Flow cytometric assessment of the postantibiotic effect of methicillin on Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 1998, 42, 1195–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marks LR; Clementi EA; Hakansson AP, Sensitization of Staphylococcus aureus to methicillin and other antibiotics in vitro and in vivo in the presence of HAMLET. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh R; Manjunatha U; Boshoff HI; Ha YH; Niyomrattanakit P; Ledwidge R; Dowd CS; Lee IY; Kim P; Zhang L; Kang S; Keller TH; Jiricek J; Barry CE 3rd, PA-824 kills nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by intracellular NO release. Science 2008, 322, 1392–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maia LB; Moura JJ, How biology handles nitrite. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 5273–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roldan MD; Perez-Reinado E; Castillo F; Moreno-Vivian C, Reduction of polynitroaromatic compounds: the bacterial nitroreductases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2008, 32, 474–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis AM; Matzdorf SS; Rice KC, Fluorescent Detection of Intracellular Nitric Oxide in Staphylococcus aureus. Bio. Protoc 2016, 6, e1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasaki S; Miura T; Nishikawa S; Yamada K; Hirasue M; Nakane A, Protective role of nitric oxide in Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. Infect. Immun 1998, 66, 1017–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ince D; Hooper DC, Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to gatifloxacin in comparison to AM-1121 and ciprofloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 2755–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huband MD; Bradford PA; Otterson LG; Basarab GS; Kutschke AC; Giacobbe RA; Patey SA; Alm RA; Johnstone MR; Potter ME; Miller PF; Mueller JP, In vitro antibacterial activity of AZD0914, a new spiropyrimidinetrione DNA gyrase/topoisomerase inhibitor with potent activity against Gram-positive, fastidious Gram-Negative, and atypical bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 467–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Halfawy OM; Klett J; Ingram RJ; Loutet SA; Murphy ME; Martin-Santamaria S; Valvano MA, Antibiotic Capture by Bacterial Lipocalins Uncovers an Extracellular Mechanism of Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance. mBio 2017, 8, e00225–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sisinni L; Cendron L; Favaro G; Zanotti G, Helicobacter pylori acidic stress response factor HP1286 is a YceI homolog with new binding specificity. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 1896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luong TT; Lee CY, Improved single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 70, 186–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luong TT; Lee CY, The arl locus positively regulates Staphylococcus aureus type 5 capsule via an mgrA-dependent pathway. Microbiology 2006, 152, 3123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fey PD; Endres JL; Yajjala VK; Widhelm TJ; Boissy RJ; Bose JL; Bayles KW, A genetic resource for rapid and comprehensive phenotype screening of nonessential Staphylococcus aureus genes. mBio 2013, 4, e00537–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forsyth RA; Haselbeck RJ; Ohlsen KL; Yamamoto RT; Xu H; Trawick JD; Wall D; Wang L; Brown-Driver V; Froelich JM; C KG; King P; McCarthy M; Malone C; Misiner B; Robbins D; Tan Z; Zhu Zy ZY; Carr G; Mosca DA; Zamudio C; Foulkes JG; Zyskind JW, A genome-wide strategy for the identification of essential genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol 2002, 43, 1387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mercier C; Chalansonnet V; Orenga S; Gilbert C, Characteristics of major Escherichia coli reductases involved in aerobic nitro and azo reduction. J. Appl. Microbiol 2013, 115, 1012–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakanishi M; Yatome C; Ishida N; Kitade Y, Putative ACP phosphodiesterase gene (acpD) encodes an azoreductase. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 46394–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang CJ; Hagemeier C; Rahman N; Lowe E; Noble M; Coughtrie M; Sim E; Westwood I, Molecular cloning, characterisation and ligand-bound structure of an azoreductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 373, 1213–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romero E; Savino S; Fraaije MW; Loncar N, Mechanistic and Crystallographic Studies of Azoreductase AzoA from Bacillus wakoensis A01. ACS Chem. Biol 2020, 15, 504–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu G; Zhou J; Lv H; Xiang X; Wang J; Zhou M; Qv Y, Azoreductase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides AS1.1737 is a flavodoxin that also functions as nitroreductase and flavin mononucleotide reductase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2007, 76, 1271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L; Le X; Li L; Ju Y; Lin Z; Gu Q; Xu J, Discovering new agents active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with ligand-based approaches. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2014, 54, 3186–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Halfawy OM; Valvano MA, Chemical communication of antibiotic resistance by a highly resistant subpopulation of bacterial cells. PLoS One 2013, 8 (7), e68874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen H; Hopper SL; Cerniglia CE, Biochemical and molecular characterization of an azoreductase from Staphylococcus aureus, a tetrameric NADPH-dependent flavoprotein. Microbiology (Reading) 2005, 151, 1433–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorries K; Schlueter R; Lalk M, Impact of antibiotics with various target sites on the metabolome of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 7151–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aros-Calt S; Castelli FA; Lamourette P; Gervasi G; Junot C; Muller BH; Fenaille F, Metabolomic Investigation of Staphylococcus aureus Antibiotic Susceptibility by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol 2019, 1871, 279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liebeke M; Meyer H; Donat S; Ohlsen K; Lalk M, A metabolomic view of Staphylococcus aureus and its ser/thr kinase and phosphatase deletion mutants: involvement in cell wall biosynthesis. Chem. Biol 2010, 17, 820–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer H; Liebeke M; Lalk M, A protocol for the investigation of the intracellular Staphylococcus aureus metabolome. Anal. Biochem 2010, 401, 250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hussein M; Karas JA; Schneider-Futschik EK; Chen F; Swarbrick J; Paulin OKA; Hoyer D; Baker M; Zhu Y; Li J; Velkov T, The Killing Mechanism of Teixobactin against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an Untargeted Metabolomics Study. mSystems 2020, 5, e00077–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaul M; Mark L; Zhang Y; Parhi AK; Lyu YL; Pawlak J; Saravolatz S; Saravolatz LD; Weinstein MP; LaVoie EJ; Pilch DS, TXA709, an FtsZ-Targeting Benzamide Prodrug with Improved Pharmacokinetics and Enhanced In Vivo Efficacy against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemotherap 2015, 59, 4845–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown S; Zhang YH; Walker S, A revised pathway proposed for Staphylococcus aureus wall teichoic acid biosynthesis based on in vitro reconstitution of the intracellular steps. Chem. Biol 2008, 15, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farha MA; MacNair CR; Carfrae LA; El Zahed SS; Ellis MJ; Tran HR; McArthur AG; Brown ED, Overcoming Acquired and Native Macrolide Resistance with Bicarbonate. ACS Infect. Dis 2020, 6, 2709–2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boles BR; Thoendel M; Roth AJ; Horswill AR, Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zingle C; Tritsch D; Grosdemange-Billiard C; Rohmer M, Catechol-rhodanine derivatives: Specific and promiscuous inhibitors of Escherichia coli deoxyxylulose phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR). Bioorg. Med. Chem 2014, 22, 3713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clark AM; Sarker M; Ekins S, New target prediction and visualization tools incorporating open source molecular fingerprints for TB Mobile 2.0. J. Cheminform 2014, 6, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clark AM; Dole K; Coulon-Spektor A; McNutt A; Grass G; Freundlich JS; Reynolds RC; Ekins S, Open Source Bayesian Models. 1. Application to ADME/Tox and Drug Discovery Datasets. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2015, 55, 1231–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Novick RP, Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991, 204, 587–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kreiswirth BN; Lofdahl S; Betley MJ; O’Reilly M; Schlievert PM; Bergdoll MS; Novick RP, The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 1983, 305, 709–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mashruwala AA; Roberts CA; Bhatt S; May KL; Carroll RK; Shaw LN; Boyd JM, Staphylococcus aureus SufT: an essential iron-sulphur cluster assembly factor in cells experiencing a high-demand for lipoic acid. Mol. Microbiol 2016, 102, 1099–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.