Abstract

Objective(s):

The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) plays a key role in several processes like inflammation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis. Several authors have proposed that genetic variations in these genes may alter their expression with subsequent cancer risk. This study aimed to examine the possible association of MKK4 rs3826392 and rs3809728 variants in Mexican patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). These variants were also compared with clinical features as sex, age, TNM stage, and tumor location.

Materials and Methods:

The study included genomic DNA from 218 control subjects and 250 patients. Genotyping of the MKK4 variants was performed using polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) procedure.

Results:

Individuals with A/T and T/T genotypes for the rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) variant showed a significantly increased risk for CRC (P=0.012 and 0.007, respectively); while individuals with the G/G genotype for the rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) variant showed a decreased risk for CRC (P=0.012). Genotypes of the MKK4 rs3809728 variant were also significantly related to colon localization and advanced TNM stage in CRC patients. T-T haplotype (rs3826392 and rs3809728) of the MKK4 gene was associated with risk in patients with CRC.

Conclusion:

The rs3826392 variant in the MKK4 gene could be a cancer protective factor, while the rs3809728 variant could be a risk factor. These variants play a significant role in CRC risk.

Key Words: Colorectal cancer, Haplotypes, MKK4, Susceptibility, Variants

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent cancers and the second cause of death worldwide (1, 2). In Mexico, the incidence and mortality rate in 2020 were 11.6/100,000 and 6/100,000 inhabitants, respectively (3). Genetic and environmental factors give individuals CRC risk (4-6). Studies on epidemiology of sporadic CRC have determined several etiologic factors related to individual lifestyles, such as alcohol and tobacco consumption, sex, body mass index, high fat diet, and processed and red meat (7-12). These factors are known as cellular stressors, and their signals are transduced by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways leading to inflammation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis (13, 14).

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) is a member of the stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) signaling pathway. The SAPK pathway is composed of several kinases working in sequential steps (MAPK, MAPKK, and MAPKKK, respectively) (15, 16). This pathway is triggered by several stimuli such as environmental stresses, inflammatory cytokines, and growth factors (16, 17). The MKK4 gene is situated in chromosome 17p11.2 and contains 11 exons (18, 19). The MKK4 protein is an essential part of the MAPK signaling pathway involved as a central mediator of the c-JUN NH2-terminal kinase cascade (JNK), which in turn is the main link to the RAS oncogenic signaling pathway (18, 20). MKK4 activates the kinases c-Jun NH2-terminal (JNK) and p38 (21) and induces several biological responses due to stress stimuli, hormones, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and growth factors (21-24).

MKK4 participates actively in the processes of apoptosis, cell differentiation, and gene transcription (23, 25-29). It has been described that overexpression of AXIN1/2 negatively regulates the Wnt pathway and leads to differential activation of MKK4 and MKK7, which play essential roles in cell growth and tumorigenesis (30). MKK4 has been identified as a metastasis suppressor gene in prostate and ovarian cancers (31, 32). Likewise, the lack of expression of the MKK4 gene has been associated with poor survival in gastric adenocarcinoma (18).

The effect of MKK4 variants on cancer susceptibility has been assessed in CRC (28, 33), lung cancer (24), acute myeloid leukemia (34), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (35), cervical cancer (36), and breast cancer (37). Among them, the rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) variant is sited in the promoter of the MKK4 gene and has been frequently shown as a protective genetic factor in several cancers, including CRC (24, 28, 34, 35, 37); however, the variant rs3809728 (-1044A>T), also located in the MKK4 promoter, has not been associated with any cancer (24, 28, 34, 35).

This study assesses for the first time, possible association of their genotypes, alleles, and haplotypes for the -1304 T>G (rs3826392) and -1044 A>T (rs3809728) variants of the MKK4 gene with the development and clinicopathological features of CRC.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Four hundred sixty-eight individuals with diagnosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma were included as stated by the anatomopathological criteria of the Specialty Hospital of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) in Guadalajara, Mexico. The CRC stage was established according to the TNM classification. The patients group consisted of 250 patients (117 females and 133 males) and the control group consisted of 218 healthy subjects (121 females and 97 males), which were not matched by age with the patients group. All individuals included in this study came from the Guadalajara metropolitan area, Mexico. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee 1305 (R-2018-1305-001) of the IMSS and was conducted following the national and international ethical standards. The samples were taken after signed informed consent. We utilized an epidemiologic questionnaire to collect personal information for all individuals and the clinical and pathological characteristics of patients were taken from the hospital records.

Genotyping analysis

DNA samples were obtained according to Miller´s method (38). The variants rs3826392 (-1304T>G) and rs3809728 (-1044A>T) in the MKK4 gene were analyzed by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) using previously described primers (25). The PCR reaction for both variants (rs3826392 and rs3809728) was performed in a total volume of 10 μl which contained: 1 X PCR buffer (100 mM Tris- HCl, 500 mM KCl, and 0.1% Triton TMX-100), 2.0 mM MgCl2, 150 μM dNTPs, 1 μM of each primer, 2 U Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase, and 100 ng DNA. The program of PCR carried out in a thermocycler was as follows: activation of the Platinum Taq DNA polymerase enzyme 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 sec, annealing (at 58 °C for variant rs3826392 and 60 °C for the variant rs3809728) for 45 sec and extension at 72 °C for 45 sec, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min.

PCR amplification products were corroborated by electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gels, then 5 μl of the DNA amplified by PCR were digested with 4 units of the MluCI restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs, USA) at 65 °C overnight for the rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) variant, and for the rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) variant with the AflII restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, USA) at 37 °C overnight.

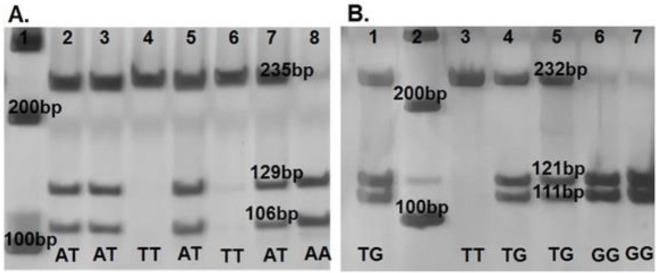

The digestion fragments were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels. The assignation of the genotypes was realized according to fragments of digestion generated by cutting site of the restriction enzymes. For analysis of the rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) variant the MluCI enzyme recognizes the sequence ^AATT and cuts before the adenine nucleotide. In samples with genotype homozygous A/A (wild type) the fragments of digestion were 129 and 106 bp. In samples with genotype A/T (heterozygous) the fragments 235, 129, and 106 were observed, and in the samples with genotype homozygous T/T (polymorphic) only one fragment of 235 bp was observed, because this does not have the site of restriction for the MluCI enzyme. To corroborate the results, randomly 10% of the samples were re-genotyped using another method and the result was 100% concordant (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Genotype representation of MKK4 variants (rs3809728 and rs3826392) on 6% polyacrylamide gels stained with AgNO3

A. MKK4 rs3809728 (-1044A>T) variant. Lane 1: 100 bp molecular marker. Lanes 2, 3, 5, 7: Individuals with genotype heterozygous (A/T) showing bands of 235+129+106 bp. Lanes 4 and 6: Individuals with genotype homozygous polymorphic (T/T) showing band of 235 bp. Lane 8: Individual with genotype homozygous wildtype (A/A) showing bands of 129+106 bp

B. MKK4 rs3826392 (-1304T>G) variant. Lanes 1, 4, 5: Individuals with genotype heterozygous (T/G) showing bands of 232+121+111 bp. Lane 2: 100 bp molecular marker. Lane 3: Individual with genotype homozygous wildtype (T/T) showing band of 232 bp. Lanes 6, 7: Individuals with genotype homozygous polymorphic (G/G) showing bands of 121+111 bp

For the assignation of genotypes of the rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) variant, the AflII enzyme recognizes the site C^TTAAG and cuts after cytosine nucleotide. In the samples with genotype homozygous T/T (wild type) only one fragment of 232 bp was observed, because this does not have the site of restriction for the AflII enzyme. In the samples with genotype T/G (heterozygous), the fragments observed were 232, 121, and 111 bp, and in samples with genotype homozygous G/G (polymorphic) the fragments were 121 and 111 bp in length (Figure 1B).

Statistical analysis

Genotype and allele frequencies were determined by direct counting in the groups. To determinate Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and to evaluate categorical variables the Chi-square test was performed. In the analysis of association of genotypes and alleles with clinical and anatomopathological characteristics, the odds ratio (OR) with confidence intervals of 95% (CI) and Chi-square with Yates´s correction was performed in SPSS 25.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Epi info 6. The analysis of haplotypes was realized in Haploview 4.2. A P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinicopathological features in the study groups

All analyzed samples of control and CRC groups were efficiently genotyped for MKK4 rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) and rs3809728 (-1044A>T) variants. Table 1 shows the demographic, clinical, and pathological data of subjects included in the study. We observed statistical differences regarding age distribution (P=0.001). The CRC individuals showed an age range of 29 to 59 years; while for the healthy individuals, the age range was of 27 to 59 years. The consumption of tobacco and drink showed statistical significance between the two groups. Concerning the clinicopathological features of the patients with CRC: 69.2% had stage III-IV tumors, 32% had metastases, and 46.8% had tumors located in the rectum.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in colorectal cancer patients and control subjects

| Characteristics | CRC group n= 250 (100%) |

Control group n= 218 (100%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years ± SD) | 58.68 (±59.5) | 37.94 (±11.74) | 0.001 |

| Age 50 years | |||

| <50 | 46 (18.4) | 173 (79.3) | 0.001 |

| >50 | 204 (81.6) | 45 (20.7) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female Male |

117 (46.8) 133 (52.3) |

121 (55.5) 97 (44.5) |

0.060 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Yes No |

87 (34.8) 163 (65.2) |

30 (13.8) 188 (86.2) |

0.001 |

| Drinking status | |||

| Yes No |

73 (29.2) 176 (70.4) |

27 (12.4) 191 (87.6) |

0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus Yes No |

70 (28.0) 180 (72.0) |

75 (34.4) 143 (65.6) |

0.143 |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes No |

84 (33.6) 166 (66.4) |

71 (32.5) 147 (67.5) |

0.813 |

| Clinical stage TNM | |||

| I II III IV |

7 (2.8) 70 (28) 93 (37.2) 80 (32) |

||

| Tumor site | |||

| Colon Rectum NA |

108 (43.2) 117 (46.8) 25 (10) |

P values were calculated by the Chi-square test

CRC: colorectal cancer; NA: Not available

MKK4 variants in patients and control subjects

The MKK4 variants in study groups showed statistical significance (Table 2). In the healthy group, the SNPs analyzed were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) (P>0.05). For the rs3826392 variant, the HWE was X2=1.55 (P=0.21); and for rs3809728 variant the HWE was X2=0.73 (P=0.39). The genotype G/G of the MKK4 rs3826392 variant (-1304T>G) was found in 24.4% (61/250) of the CRC patients and in 35.8% (78/218) of the healthy group; this difference shown statistical significance (OR=0.46; 95% CI=0.26–0.82, P=0.013). Allelic frequency differences were also statistically significant; G allele carriers has a protective effect for CRC (OR=0.70; 95% CI=0.54-0.91, P=0.009).

Table 2.

Distribution of genotypes and allelic frequencies of MKK4 polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk

| Frequencies | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | CRC group n=250 (%) | Control group n=218 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P- value |

| MKK4 (rs3826392) | ||||

| T/T | 47 (18.8) | 28 (12.8) | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| T/G | 142 (56.8) | 112 (51.4) | 0.75 (0.44-1.28) | 0.364 |

| G/G | 61 (24.4) | 78 (35.8) | 0.46 (0.26-0.82) | 0.013 |

| T/G+G/G vs. T/T | 203 (81.2) | 190 (87.1) | 0.63 (0.38-1.05) | 0.104 |

| Allele | ||||

| T | 236 (47.2) | 168 (38.5) | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| G | 264 (52.8) | 268 (61.5) | 0.70 (0.54-0.91) | 0.009 |

| MKK4 (rs3809728) | ||||

| A/A | 14 (5.6) | 29 (13.3) | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| A/T | 131 (52.4) | 109 (50.0) | 2.48 (1.25-4.94) | 0.012 |

| T/T | 105 (42.0) | 80 (36.7) | 2.71 (1.34-5.48) | 0.007 |

| A/T+T/T vs. A/A | 236 (94.4) | 189 (86.7) | 2.58 (1.32-5.03) | 0.006 |

| Allele | + | |||

| A | 159 (31.8) | 167 (38.3) | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| T | 341 (68.2) | 269 (61.7) | 1.33 (1.01-1.74) | 0.043 |

CRC: Colorectal cancer; Bold text highlights statistically significant findings; P-values were calculated by the chi-square test

Concerning the MKK4 rs3809728 variant (-1044A>T), the patients and the control group individuals exhibited significant differences between A/T and T/T genotypes (P=0.012 and P=0.007, respectively). Under a dominant pattern (A/T+T/T vs A/A) it showed that the allele T is associated with CRC risk (OR=2.58; 95% CI=1.32-5.03, P=0.006). Likewise, allele frequencies analysis showed that the allele T is associated with susceptibility to CRC (OR=1.33; 95% CI=1.01-1.74, P=0.043).

MKK4 genotypes by sex and age

Table 3 shows analysis of the MKK4 genotypes regarding sex and age. Decreased risk was observed in CRC female patients in presence of the G/G genotype for the rs3826392 variant (OR=0.35; 95% CI=0.15-0.81, P=0.023); in addition, a marginal association was observed for females with CRC regarding TG+GG dominant model (OR=0.46; 95% CI=0.22-0.96, P=0.057). Regarding age, patients over 50 years and carrying the G/G genotype showed a protective effect (OR=0.21; 95% CI=0.07-0.66, P=0.010).

Table 3.

Association of MKK4 polymorphisms with sex and age in CRC patients and controls

| rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients/Control | OR (95% CI); P -value | |||||

| V ariable | TT | TG | GG | TG versus TT | GG versus TT | TG+GG versus TT |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 23/15 | 76/45 | 34/37 | 1.10 (0.52-2.32); 0.950 | 0.59 (0.26-1.33); 0.290 | 0.87 (0.42-1.78); 0.849 |

| Female | 24/13 | 66/67 | 27/41 | 0.53 (0.25-1.13); 0.145 | 0.35 (0.15-0.81); 0.023 | 0.46 (0.22-0.96); 0.057 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 | 10/23 | 30/86 | 6/64 | 0.80 (0.34-1.87); 0.775 | 0.21 (0.07-0.66); 0.010 | 0.55 (0.24-1.26); 0.233 |

| >50 | 37/5 | 112/26 | 55/14 | 0.58 (0.20-1.62); 0.418 | 0.53 (0.17-1.59); 0.380 | 0.56 (0.20-1.52); 0.357 |

| rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) | ||||||

| Patients/Control | OR (95% CI); P -value | |||||

| Variable | AA | AT | TT | AT versus AA | TT versus AA | AT+TT versus AA |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 8/19 | 66/38 | 59/40 | 4.12 (1.64-10.3); 0.003 | 3.50 (1.39-8.77); 0.010 | 3.80 (1.58-9.11); 0.003 |

| Female | 6/10 | 65/71 | 46/40 | 1.52 (0.52-4.43); 0.605 | 1.91 (0.63-5.74); 0.366 | 1.66 (0.58-4.74); 0.479 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 | 1/23 | 26/88 | 19/62 | 6.79 (0.87-52.7); 0.070 | 7.04 (0.89-55.6); 0.069 | 6.90 (0.90-52.5); 0.060 |

| >50 | 13/6 | 105/21 | 86/18 | 2.30 (0.78-6.76); 0.214 | 2.20 (0.73-6.57); 0.259 | 2.26 (0.80-6.31); 0.199 |

Bold text highlights statistically significant findings

For the rs3809728 variant we observed that the male patients carrying A/T and TT genotypes showed an increased risk (OR=4.12; 95% CI=1.64-10.32, P=0.003 and OR=3.50; 95% CI=1.39-8.77, P=0.010, respectively); and this association was observed with the dominant model (OR=3.80; 95% CI=1.58-9.11, P=0.003). Regarding the age, we did not observe a statistical significance.

MKK4 genotypes by anatomopathological features

Association of MKK4 genotypes with TNM stages and tumor site are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Analysis adjustment by age showed that the patients with presence of G/G genotype for the rs3826392 variant have a protective effect for TNM III+IV stages (OR=0.45; 95% CI=0.23-0.87, P=0.027); while, individuals with the T/T genotype for the rs3809728 variant, have a marginally significant difference for TNM III+IV stages (OR=2.28; 95% CI=1.03- 5.03, P=0.058) (Table 4). In contrast, in the analysis by tumor site adjusted by age; we observed an increased risk for developing tumors in colon in patients with A/T and T/T genotypes for the rs3809728 variant (OR=4.43; 95% CI=1.28-15.24, P=0.019 and OR=4.35; 95% CI=1.24-15.21, P=0.025, respectively) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Association between TNM stage and MKK4 rs3826392 and rs3809728 polymorphisms in CRC patients and controls

| rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype |

TNM Stage

I+II n=77 (%) |

TNM stage

III+IV n=173 (%) |

Control

n=218 (%) |

I+II stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

I+II stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) * |

P -value* |

III+IV stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

III+IV stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) * |

P- value* | ||

| T/T | 14 (18.2) | 33 (19.1) | 28 (12.8) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||||||

| T/G | 42 (54.5) | 100 (57.8) | 112 (51.4) | 0.75 (0.36-1.56) | 0.563 | 1.03 (0.42-2.47) | 1.000 | 0.75 (0.42-1.34) | 0.418 | 0.68 (0.37-1.23) | 0.262 | ||

| G/G | 21 (27.3) | 40 (23.1) | 78 (35.8) | 0.53 (0.24-1.20) | 0.189 | 0.80 (0.31-2.06) | 0.840 | 0.43 (0.23-0.81) | 0.014 | 0.45 (0.23-0.87) | 0.027 | ||

| T/G+G/G | 63 (81.2) | 140 (80.9) | 190 (87.1) | 0.66 (0.32-1.33) | 0.335 | 0.93 (0.40-2.18) | 1.000 | 0.62 (0.36-1.08) | 0.122 | 0.58 (0.33-1.04) | 0.091 | ||

| rs3809728 (-1044A>T) | |||||||||||||

| Genotype |

TNM stage I+II

n= 77 (%) |

TNM stage III+IV n=173 (%) |

Control

n=218 (%) |

I+II stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

I+II stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) * |

P -value* |

III+IV stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

III+IV stage

vs

control

OR (95% CI) * |

P- value* | ||

| A/A | 4 (5.2) | 10 (5.8) | 29 (13.3) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||||||

| A/T | 42 (54.5) | 89 (51.4) | 109 (50.0) | 2.79 (0.92-7.42) | 0.096 | 2.92 (0.83-10.22) | 0.131 | 2.36 (1.09-5.12) | 0.039 | 1.91 (0.87-4.17) | 0.140 | ||

| T/T | 31 (40.3) | 74 (42.8) | 80 (36.7) | 2.80 (0.91-8.65) | 0.103 | 2.77 (0.77-9.95) | 0.171 | 2.68 (1.22-5.88) | 0.019 | 2.28 (1.03-5.03) | 0.058 | ||

| A/T+T/T | 73 (94.8) | 163 (94.2) | 189 (86.7) | 2.80 (0.95-8.24) | 0.083 | 2.86 (0.84-9.75) | 0.127 | 2.50 (1.18-5.28) | 0.021 | 2.07 (0.97-4.39) | 0.078 | ||

*Adjust for age in >50 years. Bold text highlights statistically significant findings

Table 5.

Association between tumor location and polymorphisms rs3826392 and rs3809728 of MKK4 in CRC patients and controls

| rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) | |||||||||||

| Genotype |

Colon cancer

n=108 (%) |

Rectal cancer

n=117 (%) |

Control

n= 218 (%) |

Colon cancer vs control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

Colon cancer vs control

OR (95% CI) * |

P- value * |

Rectal cancer

vs

control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

Rectal cancer vs control

OR (95% CI)* |

P- value* |

| T/T | 20 (18.5) | 24 (20.5) | 28 (12.8) | 1. 00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||||

| T/G | 60 (55.5) | 66 (56.4) | 112 (51.4) | 0.75 (0.39-1.44) | 0.487 | 0.63 (0.32-1.26) | 0.267 | 0.68 (0.36-1.28) | 0.308 | 0.79 (0.39-1.60) | 0.647 |

| G/G | 28 (26.0) | 27 (23.1) | 78 (35.8) | 0.50 (0.24-1.03) | 0.088 | 0.49 (0.23-1.04) | 0.098 | 0.40 (0.20-0.81) | 0.016 | 0.53 (0.25-1.15) | 0.163 |

| T/G+G/G | 88 (81.5) | 93 (79.5) | 190 (87.1) | 0.64 (0.34-1.24) | 0.232 | 0.54 (2.66-12.66) | 0.008 | 0.57 (0.31-1.03) | 0.091 | 0.69 (0.35-1.34) | 0.363 |

| rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) | |||||||||||

| Genotype |

Colon cancer

n=108 (%) |

Rectal cancer

n=117 (%) |

Control n=218 (%) |

Colon cancer vs control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

Colon cancer vs control

OR (95% CI) * |

P- value * |

Rectal cancer

vs

control

OR (95% CI) |

P- value |

Rectal cancer vs control

OR (95% CI)* |

P- value* |

| A/A | 3 (2.8) | 9 (7.7) | 29 (13.3) | 1. 00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||||

| A/T | 60 (55.5) | 59 (50.5) | 109 (50.0) | 5.32 (1.55-18.20) | 0.006 | 4.43 (1.28-15.24) | 0.019 | 1.74 (0.77-3.92) | 0.244 | 1.43 (0.60-3.37) | 0.539 |

| T/T | 45 (41.7) | 49 (41.8) | 80 (36.7) | 5.43 (1.56-18.85) | 0.006 | 4.35 (1.24-15.21) | 0.025 | 1.97 (0.86-4.51) | 0.151 | 1.81 (0.75-4.32) | 0.251 |

| A/T+T/T | 105 (97.2) | 108 (92.3) | 189 (86.7) | 5.37 (1.59-18.05) | 0.004 | 4.39 (1.30-14.83) | 0.017 | 1.84 (0.84-4.03) | 0.172 | 1.59 (0.69-3.62) | 0.356 |

*Adjust for age in > 50 years. Bold text highlights statistically significant findings

MKK4 Haplotypes

The haplotype analysis showed that the combination T-T of rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) and rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) alleles in the MKK4 gene increased the risk for developing CRC (OR=1.82; 95% CI=1.19-2.79, P=0.007) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Haplotype analysis in the MKK4 gene in CRC patients

| Haplotype | Frequencies | X 2 |

CRC Risk

OR (95% CI) |

P -value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MKK4 gene | CRC group N= 250 (%) | Control group N= 218 (%) | ||||

| rs3826392- rs3809728 | ||||||

| G | T | 91 (36.6) | 90 (41.3) | 0.974 | 0.81 (0.56-1.18) | 0.323 |

| T | T | 79 (31.6) | 44 (20.4) | 7.255 | 1.82 (1.19-2.79) | 0.007 |

| G | A | 41 (16.2) | 44 (20.2) | 0.881 | 0.77 (0.48-1.24) | 0.347 |

| T | A | 39 (15.6) | 40 (18.1) | 0.446 | 0.82 (0.50-1.33) | 0.504 |

CRC: colorectal cancer; Bold text highlights statistically significant findings

Discussion

Previous investigations have pinpointed a considerable number of gene mutations associated with CRC; however, some results are controversial regarding the potential effect of the MKK4 gene on CRC susceptibility. Specifically, the rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) variant has been related to a protective effect on CRC development in the Chinese population (26); meanwhile, the rs3809728 (-1044 A>T) variant, although frequently studied, has not been associated with CRC. With this background, the objective of this study was to evaluate two SNVs (rs3826392 and rs3809728) of the MKK4 gene and their effects on CRC. Our results suggest that rs3826392 and rs3809728 variants of the MKK4 gene participate in the development of CRC in the Mexican population studied here.

Among the 250 analyzed patients, we observed a significant increase in CRC in people over 50 years (81.6%), which is consistent with the results of several previous studies (39-41). The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in 2019 indicated that the average age at the time of colon cancer diagnosis is approximately 70 years, while, for rectal cancer, the average age is approximately 63 years. Although CRC can occur at younger ages, its risk increases preponderantly in people over 50 years of age.

In this study, cancer risk was evident in individuals with A/T and T/T genotypes for the rs3809728 variant; such a finding had not been previously reported in patients with different cancers analyzed, including CRC (24, 28, 34, 35, 37). Meanwhile, a protective effect was observed among patients carrying the G/G genotype of the rs3826392 (-1304 T>G) variant.

Studies have shown that the polymorphic G allele of the rs3826392 variant enhances the transcriptional activity of the MKK4 gene compared with the wild type T allele, suggesting that the -1304T>G change may increase the MKK4 gene expression. As a member of the MAPK signaling pathway, the tumorigenic role of the MKK4 protein is complex. Confirmation of the MKK4 gene as a tumor suppressor has been obtained from different cancer cell lines in which, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or presence of missense variants, produce a loss of function of MKK4 (23, 27, 34).This loss of function due to mutations or decreased expression of MKK4 has been described in patients with biliary cancer (42).

On the other hand, studies in breast and pancreas cancer demonstrate that MKK4 has a pro-oncogenic activity (42, 43). Overexpression of the MKK4 gene has been observed in gastric and prostate cancers (18, 44). A bioinformatic analysis realized by Wei et al. in 2009 showed that the T allele of the rs3826392 variant has a binding site for the transcription factor Nkx-2 (28), which plays an oncogenic role in several cancers like prostate, lung, Ewing´s sarcoma, and neuroendocrine tumors (28, 45-48). They also demonstrated that this allele increases the expression of MKK4. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that Nkx-2 may inhibit MKK4 expression and lead to carcinogenesis in CRC tissue; however, for the rs3809728 A>T variant, no difference in binding factors was observed in the Wei et al. report (28).

In our study, haplotype analysis showed that the T wild type allele in the rs3826392 (1304T>G) variant and the polymorphic T allele of the rs3809728 (-1044A>T) variant (haplotype T-T) is also associated with increased susceptibility to CRC.

Regarding age and sex of the patients studied here, females under 50 years old and carrying the G/G genotype for the rs3826392 variant showed a significantly decreased risk. This decreased risk was also found in 2009 by Wei et al. in Chinese patients with sporadic CRC and other types of cancer (28). Meanwhile, male patients with presence of A/T and T/T genotypes for the rs3809728 variant have increased CRC susceptibility. Such an observation has not been previously reported.

On the other hand, in the TNM stage and tumor site evaluation, our data suggest that patients over 50 and with A/T and T/T genotypes for the rs3809728 variant have an increased risk to reach advanced TNM stages (TNM III+IV). This susceptibility, which means a poorer prognosis in these patients, is probably related to unknown mechanisms that would allow a faster tumor progression. Inversely, the decreased risk observed in patients over 50 years with the rs3826392 risk variant is related to a better prognosis in these patients, possibly related to a slower tumor progression.

Regarding tumor location, we observed that patients aged over 50 years had added susceptibility to develop colon cancer in the presence of the A/T and T/T genotypes for the rs3809728 variant. In contrast, for the rs3826392 variant, the patients aged over 50 years had a protective effect on rectum cancer in the presence of the G/G genotype. In support of these results, several clinical and biological features indicate that colon cancer is different from rectum cancer and these differences are related to embryological origin, function, anatomy, genetics, clinical manifestation, treatment response, and clinical outcome (49-54), and consequently, the therapies for rectal and colon cancer are also distinct, depending on the TNM stage (55). In studies realized in the Mexican population, patients with CRC also showed a greater predisposition to develop tumors in the colon (56, 57).

Conclusion

As previously reported, our results showed that the MKK4 rs3826392 variant operates as a protective factor for CRC; however, for the first time, these results also reveal that the rs3809728 variant is associated with an increased risk of CRC. Some genotypes of rs3826392 and rs3809728 variants are related to the TNM stage and tumor site in these patients. Interestingly, an association of the T-T haplotype (rs3826392 and rs3809728 alleles) with CRC risk was also demonstrated in this analysis. Further studies, including analysis of these variants in larger samples and functional studies, are necessary to confirm our results. Nevertheless, it is acceptable to suggest that the MKK4 rs3826392 and rs3809728 variants can be considered useful biomarkers of prognosis and tumor site in CRC.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grants from “Fondo de Investigación en Salud del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social” (FIS/IMSS/PROT/G18/1822).

Authors’ Contributions

MARR and PBN designed the experiments; KCEMC, AMSS, TDPR, MEMC performed experiments and collected data; KCEMC and SEFM discussed the results and strategy; MARR, PBN, MPGA, SEFM Supervised, directed and managed the study; KCEMC, AMSS, PBN, M PGA, TDPR, MEMC, SEFM, and MARR Final approved of the version to be published.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Globocan. Colorectal cancer. 2020. URL: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/10_8_9-Colorectum-factsheet.pdf [Accesed: April 15, 2021]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Globocan. Mexico. 2020. URL: http://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/484-mexico-fact-sheets.pdf [Accesed: April 15, 2021]

- 4.Carr PR, Weigl K, Edelmann D, Jansen L, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H, et al. Estimation of absolute risk of colorectal cancer based on healthy lifestyle, genetic risk, and colonoscopy status in a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:129–138. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ocvirk S, Wilson AS, Appolonia CN, Thomas TK, O’Keefe SJD. Fiber, fat, and colorectal cancer: New insight into modifiable dietary risk factors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:62. doi: 10.1007/s11894-019-0725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho YA, Lee J, Oh JH, Chang HJ, Sohn DK, Shin A, et al. Genetic risk score, combined lifestyle factors and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:1033–1040. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2533–2547. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsong WH, Koh WP, Yuan JM, Wang R, Sun CL, Yu MC. Cigarettes and alcohol in relation to colorectal cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:821–827. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thanikachalam K, Khan G. Colorectal cancer and nutrition. Nutrients. 2019;11:164. doi: 10.3390/nu11010164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713–732. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song M, Chan AT, Sun J. Influence of the gut microbiome, diet, and environment on risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:322–340. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin A, Li H, Shu X-O, Yang G, Gao Y-T, Zheng W. Dietary intake of calcium, fiber and other micronutrients in relation to colorectal cancer risk: Results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Int J cancer. 2006;119:2938–2942. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–3290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Y-J, Pan W-W, Liu S-B, Shen Z-F, Xu Y, Hu L-L. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19:1997–2007. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.English J, Pearson G, Wilsbacher J, Swantek J, Karandikar M, Xu S, et al. New insights into the control of MAP kinase pathways. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:255–270. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dogan M, Guresci S, Acikgoz Y, Ergun Y, Kos FT, Bozdogan O, et al. Is there any correlation among MKK4 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4) expression, clinicopathological features, and KRAS/NRAS mutation in colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20:851–859. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2020.1784728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham SC, Gallmeier E, Hucl T, Dezentje DA, Calhoun ES, Falco G, et al. Targeted deletion of MKK4 in cancer cells: a detrimental phenotype manifests as decreased experimental metastasis and suggests a counterweight to the evolution of tumor-suppressor loss. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5560–5564. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diao D, Wang L, Zhang J-X, Chen D, Liu H, Wei Y, et al. Mitogen/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase-5 promoter region polymorphisms affect the risk of sporadic colorectal cancer in a southern Chinese population. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31:342–349. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuenda A. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:581–587. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(00)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland CL, Heath AW, Pelech SL, Young PR, Gold MR. Differential activation of the ERK, JNK, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases by CD40 and the B cell antigen receptor. J Immunol. 1996;157:3381–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng DH, Perry WL 3rd, Hogan JK, Baumgard M, Bell R, Berry S, et al. Human mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 as a candidate tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4177–4182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B, Chen D, Yang L, Li Y, Ling X, Liu L, et al. A functional variant (-1304T>G) in the MKK4 promoter contributes to a decreased risk of lung cancer by increasing the promoter activity. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1405–1411. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida BA, Dubauskas Z, Chekmareva MA, Christiano TR, Stadler WM, Rinker-Schaeffer CW. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4/stress-activated protein/Erk kinase 1 (MKK4/SEK1), a prostate cancer metastasis suppressor gene encoded by human chromosome 17. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5483–5487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada SD, Hickson JA, Hrobowski Y, Vander Griend DJ, Benson D, Montag A, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) acts as a metastasis suppressor gene in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6717–6723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakayama K, Nakayama N, Davidson B, Katabuchi H, Kurman RJ, Velculescu VE, et al. Homozygous deletion of MKK4 in ovarian serous carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:630–634. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.6.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei Y, Wang L, Lan P, Zhao H, Pan Z, Huang J, et al. The association between -1304T>G polymorphism in the promoter of MKK4 gene and the risk of sporadic colorectal cancer in southern Chinese population. Int J cancer. 2009;125:1876–1883. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burotto M, Chiou VL, Lee J-M, Kohn EC. The MAPK pathway across different malignancies: a new perspective. Cancer. 2014;120:3446–3456. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Neo SY, Wang X, Han J, Lin SC. Axin forms a complex with MEKK1 and activates c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase through domains distinct from Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35247–35254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spillman MA, Lacy J, Murphy SK, Whitaker RS, Grace L, Teaberry V, et al. Regulation of the metastasis suppressor gene MKK4 in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson VL, Shalhav O, Otto K, Kawai T, Gorospe M, Rinker-Schaeffer CW. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase kinase 1 protein expression is subject to translational regulation in prostate cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:501–508. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai R, Yuan C, Zhou F, Ni L, Gong Y, Xie C. Evaluation of the association between the -1304T>G polymorphism in the promoter of the MKK4 gene and the risk of colorectal cancer: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:144. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.03.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang L, Zhou P, Sun A, Zheng J, Liu B, You Y, et al. Functional variant (-1304T>G) in the MKK4 promoter is associated with decreased risk of acute myeloid leukemia in a southern Chinese population. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1462–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu M, Zheng J, Zhang L, Jiang L, You Y, Jiang M, et al. The association between -1304T>G polymorphism in the promoter of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 gene and the risk of cervical cancer in Chinese population. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31:1167–1173. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iqbal B, Masood A, Lone MM, Lone AR, Dar NA. Polymorphism of metastasis suppressor genes MKK4 and NME1 in Kashmiri patients with breast cancer. Breast J. 2016;22:673–677. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng J, Liu B, Zhang L, Jiang L, Huang B, You Y, et al. The protective role of polymorphism MKK4-1304 T>G in nasopharyngeal carcinoma is modulated by Epstein-Barr virus’ infection status. Int J cancer. 2012;130:1981–1990. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J cancer. 2015;136:359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alberts SR Citrin. Cancer Management. 2016. [Accesed: April 15, 2021]. https://www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management/colon-rectal-and-anal-cancers .

- 42.Su GH, Hilgers W, Shekher MC, Tang DJ, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, et al. Alterations in pancreatic, biliary, and breast carcinomas support MKK4 as a genetically targeted tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2339–2342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L, Pan Y, Dai J Le. Evidence of MKK4 pro-oncogenic activity in breast and pancreatic tumors. Oncogene. 2004;23:5978–5985. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham SC, Kamangar F, Kim MP, Hammoud S, Haque R, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, et al. MKK4 status predicts survival after resection of gastric adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1095–1099. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta A, Wang Y, Browne C, Kim S, Case T, Paul M, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in the 12T-10 transgenic prostate mouse model mimics endocrine differentiation of pancreatic beta cells. Prostate. 2008;68:50–60. doi: 10.1002/pros.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riemenschneider MJ, Koy TH, Reifenberger G. Expression of oligodendrocyte lineage genes in oligodendroglial and astrocytic gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;107:277–282. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seike M, Gemma A, Hosoya Y, Hosomi Y, Okano T, Kurimoto F, et al. The promoter region of the human BUBR1 gene and its expression analysis in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;38:229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith R, Owen LA, Trem DJ, Wong JS, Whangbo JS, Golub TR, et al. Expression profiling of EWS/FLI identifies NKX2 2 as a critical target gene in Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heald RJ, Moran BJ. Embryology and anatomy of the rectum. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;15:66–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199809)15:2<66::aid-ssu2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J cancer. 2002;101:403–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li F, Lai M. Colorectal cancer, one entity or three. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009;10:219–229. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanz-Pamplona R, Cordero D, Berenguer A, Lejbkowicz F, Rennert H, Salazar R, et al. Gene expression differences between colon and rectum tumors. Clin cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2011;17:7303–7312. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slattery ML, Wolff E, Hoffman MD, Pellatt DF, Milash B, Wolff RK. MicroRNAs and colon and rectal cancer: differential expression by tumor location and subtype. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:196–206. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paschke S, Jafarov S, Staib L, Kreuser ED, Maulbecker Armstrong C, Roitman M, et al. Are colon and rectal cancer two different tumor entities? A proposal to abandon the term colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2577. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamas K, Walenkamp AME, de Vries EGE, van Vugt MATM, Beets Tan RG, van Etten B, et al. Rectal and colon cancer: Not just a different anatomic site. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosales-Reynoso MA, Zepeda-López P, Saucedo-Sariñana AM, Pineda-Razo TD, Barros-Núñez P, Gallegos-Arreola MP, et al. GSK3β polymorphisms are associated with tumor site and TNM stage in colorectal cancer. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosales-Reynoso MA, Saucedo-Sariñana AM, Contreras-Díaz KB, Márquez-González RM, Barros-Núñez P, Pineda-Razo TD, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in APC, DVL2, and AXIN1 are associated with susceptibility, advanced TNM stage or tumor location in colorectal cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;249:173–183. doi: 10.1620/tjem.249.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]