Abstract

Oral human papillomavirus (HPV) is associated with increasing rates of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) in men. Sequential infection from one site to another has been demonstrated at the cervix and anus. Thus, risk of an oral HPV infection following a genital infection of the same type in the HPV Infection in Men study was investigated. Samples from 3,140 men enrolled in a longitudinal cohort were assessed for sequential genital to oral infection with one of nine HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58); and then also sequential, same-type oral to genital infection. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) compared rates of oral HPV among men with and without prior genital infection of the same type. Risk of sequential HPV infections were assessed using Cox proportional hazards model. Incidence of an oral HPV infection was significantly higher among men with a prior genital infection of the same type for any of the 9 HPV types (IRR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.7–3.0). Hazard ratio of a sequential genital to oral HPV infection was 2.3 (95% CI: 1.7–3.1) and 3.5 (95% CI: 1.9–6.4) for oral to genital infection. Both changed minimally after adjustment for age, country, circumcision, alcohol use, lifetime sexual partners and recent oral sex partners. HPV infections at one site could elevate risk of a subsequent genital or oral HPV infection of the same type in men, emphasizing the importance of vaccination to prevent all HPV infections.

Keywords: HPV, sequential infection, men

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a cause of oropharyngeal cancer (OPC).1 Over the last several decades OPC caused by smoking and alcohol has decreased, while the proportion and incidence of OPC caused by HPV has increased, predominantly among men.2, 3 Among men in the U.S., HPV-associated OPC has an age-adjusted incidence rate near 8 per 100,000 and accounts for 78% of all HPV-associated cancers in men. In contrast, among women the age-adjusted HPV-associated OPC incidence rate is nearly 2 per 100,000 and accounts for 11% of their HPV-associated cancers.4

The natural history of oral HPV appears to be different for men and women with a higher prevalence of HPV detected among OPC tumor specimens from men.3 Further, in a nationally representative sample of the US, oral HPV prevalence was significantly higher among healthy, cancer free men compared to women (10.1% vs 3.6%, respectively).5

Studies of HPV infection at other anatomic sites, including cervical HPV infection in women and anal HPV infection in both women and men, have demonstrated evidence of what appears to be sequential infection from one anatomic site to another. Among women, sequential infection from the cervix to the anus has been observed in the absence of receptive anal sex.6–8 Risk of anal HPV infection was 2-fold higher among women with a prior cervical HPV infection of the same type, although 63% of those cases reported no history of anal sex.6 Similarly, among men who exclusively have sex with women (MSW), prior genital HPV infection conferred a significantly higher risk of a subsequent anal infection of the same HPV type (adjusted HR: 2.80; 95% CI: 1.32–5.99).9 Thus, autoinoculation by HPV infection at one anatomic site to infection at a different anatomic site may contribute to risk of secondary, sequential infections.

At this time, no studies have investigated sequential infection from the genitals to the oral epithelium specifically among men. The primary aim of the current study was to assess type-specific sequential acquisition of oral HPV infection following a genital HPV infection for 9 HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58) among men in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study cohort. Over the course of the study the question arose as to whether same-type, sequential infection also occurred in the opposite direction, from the oral cavity to the genitals. Therefore, secondary to the first aim, we also investigated the risk of prior oral HPV infection on the type-specific sequential acquisition of genital HPV.

Methods

Study Population

Study subjects were recruited as a part of the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study, which recruited 4,123 men from the United States, Brazil, and Mexico from 2005 to 2009. Eligible subjects were followed every 6 months and included men (1) 18–70 years-old; (2) residing within one of the study locations; (3) no previous diagnosis of penile or anal cancers or genital warts; (5) no symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and no current receipt of STI treatment; (6) no current participation in an HPV vaccine study; (7) no history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or AIDS; (8) no history of imprisonment, homelessness, or drug-abuse treatment during the past 6 months; and (9) willing to comply with the scheduled study visits. Complete, detailed description of the HIM study methods has been previously published.10, 11 After providing consent, demographic information and behavior data were obtained using computer-assisted self-interviewing. Approval was obtained from the human subjects committees of the University of South Florida (United States), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Brazil), Centro de Referencia e Treinamento em Doencas Sexualmente Transmissíveis e AIDS (Brazil), and Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica de Mexico (Mexico).

Genital and Oral HPV DNA Samples

Genital cell samples from the coronal sulcus/glans penis, penile shaft, and scrotum were collected at each follow-up visit with pre-wetted Dacron–tipped swabs, which were later combined to form a single genital sample.10, 11 Genital HPV DNA was extracted by the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) and HPV genotyping was performed using the Roche Linear Array assay to detect 37 HPV genotypes, and human β-globin was tested to assess specimen adequacy.12

Oral gargles were obtained from a sub-cohort enrolled in the study between 2007–2009. Study subjects with two or more archived oral gargle specimens collected ≥6 months from either an annual or intervening visit were included in the sub-cohort (n=3,166). Oral HPV DNA was extracted from oral gargle cell pellets using the automated BioRobot MDx (Qiagen) and HPV genotyping was performed using SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 system (DDL Diagnostic Laboratory, Rijswik, the Netherlands). Details regarding this assay are available elsewhere.13

Statistical Analysis

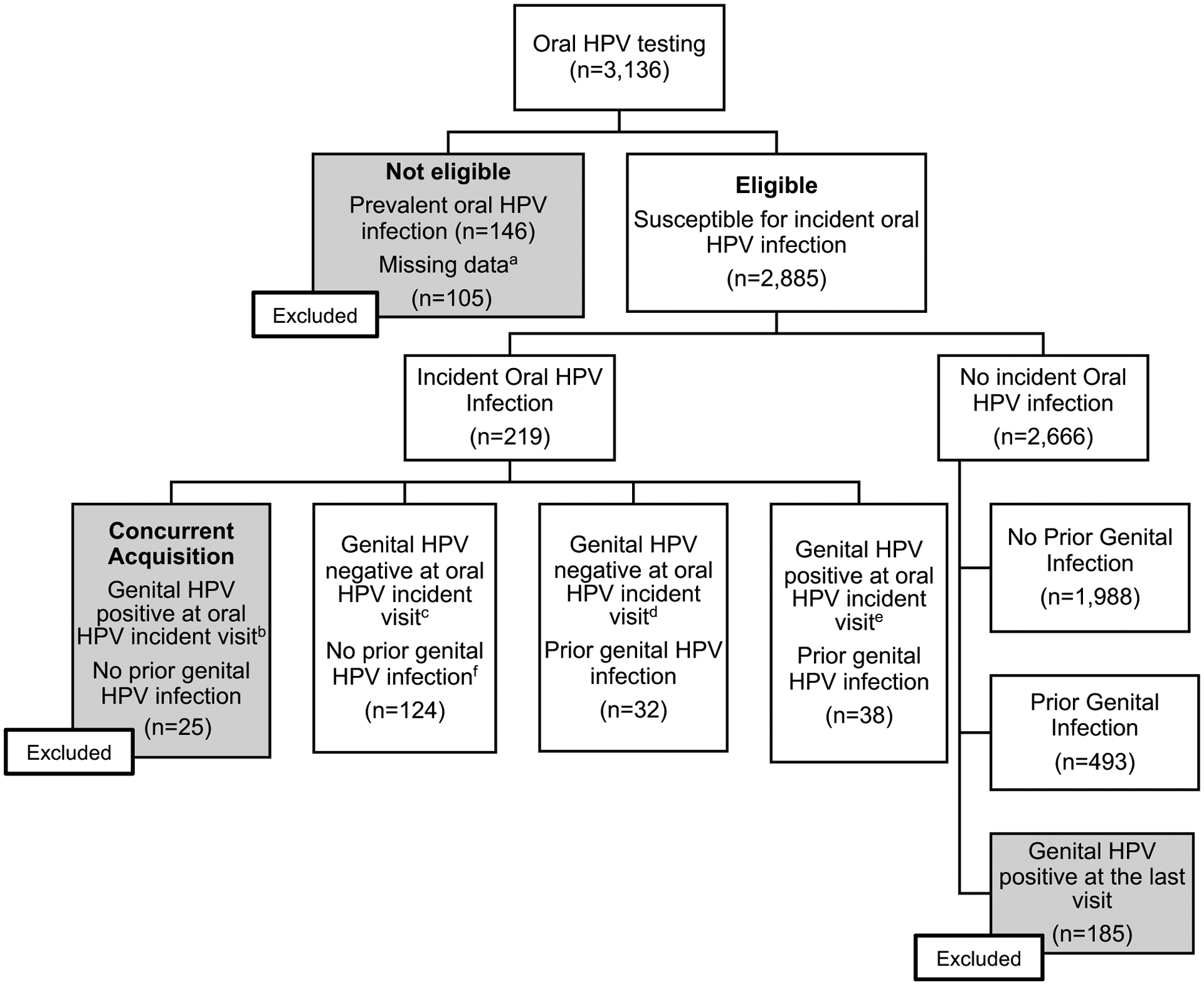

HPV types in the 9-valent vaccine (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) were assessed for sequential, type-specific genital to oral infections because these types represent nearly all HPV types detected at the oral/pharynx14. Subjects with a genital and oral HPV DNA sample were included in this analysis (Figure 1). Subjects were excluded if they were oral HPV positive at their first oral gargle collection (prevalently detected oral HPV), or missing data such as a valid genital HPV result or survey data. Eligible subjects were assessed for incident oral HPV infection throughout follow-up. Subjects were categorized as either with or without a prior genital HPV infection. Among subjects with an incident oral HPV infection, prior genital HPV infection status was determined by the presence of an HPV infection of the same type at the study visit just prior (6 months) to the incident oral HPV positive visit. Among subjects with no incident oral HPV infection detected at any visit, their last visit with an oral HPV test was used for sequential analysis. Their prior genital HPV infection status was determined by the presence of a genital HPV infection at the visit just prior to their last oral visit (6 months).

Figure 1.

Selection of study population from the HPV infection in Men (HIM) study for evaluation of sequential genital to oral HPV infection.

aPrevalent oral HPV infections (n=146). Subjects with missing data (n=105) included subjects with 1) only one-time oral test (n=10); 2) no valid prior genital HPV test (n=91); 3) no survey data (n=4).

bIncident genital and oral infections occurred at the same time and do not represent a sequential genital to oral infection. Thus, these subjects were excluded from sequential oral analyses. The number of oral HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 4; HPV 11, 0; HPV 16, 4; HPV 18, 5; HPV 31, 4; HPV 33, 1; HPV 45, 1; HPV 52, 8; and HPV 58, 0. Number of men infected with multiple types of oral HPV: 2.

cThe number of oral HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 8; HPV 11, 10; HPV 16, 28; HPV 18, 12; HPV 31, 12; HPV 33, 3; HPV 45, 5; HPV 52, 64; and HPV 58, 3. Number of men infected with multiple types or oral HPV: 16.

d The number of oral HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 5; HPV 11, 1; HPV 16, 9; HPV 18, 1; HPV 31, 2; HPV 33, 3; HPV 45, 3; HPV 52, 11; and HPV 58, 0. Number of men infected with multiple types or oral HPV: 3.

e The number of oral HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 4; HPV 11, 1; HPV 16, 15; HPV 18, 4; HPV 31, 2; HPV 33, 1; HPV 45, 0; HPV 52, 13; and HPV 58, 1. Number of men infected with multiple types or oral HPV: 3

Men with incident detected oral HPV infections were categorized into one of 4 groups: (1) subjects without a prior genital HPV infection but positive for genital HPV at the time of the incident oral HPV-positive visit (concurrent HPV acquisition), (2) subjects without a prior genital HPV infection and negative for genital HPV at the time of the incident oral HPV-positive visit, (3) subjects with a prior genital HPV infection and negative for genital HPV at the time of the incident oral HPV-positive visit, and (4) subjects with a prior genital HPV infection and still positive for genital HPV at the time of the incident oral HPV-positive visit. Subjects in group 1 who had concurrent genital and oral infections were excluded from sequential analyses (n=25). Therefore, to ensure uniformity in selection criteria, men who did not develop an incident oral HPV infection and had no prior genital HPV infection, but became genital HPV positive at the last oral visit were also excluded. Characteristics of subjects who were susceptible to an incident oral HPV infection were compared by their prior genital HPV infection status, using χ2 tests.

Oral HPV Incidence Rate.

To first understand the incidence of oral HPV infections in this cohort by prior genital infection status, the incident rate and corresponding rate ratios were calculated. Subjects without a prevalent oral HPV infection constituted the at-risk population for the incidence rate calculations. Oral HPV infection incidence rates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by the prior genital HPV infection status using Poisson regression models adjusted for country and age with time of exposure calculated as person-months between the prior study visit (6 months) and oral HPV detected. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated for each of the 9 HPV types comparing the prior genital and no prior genital infection groups. Participants were also categorized by 9vHPV types, the low-risk HPV types (HPV 6 and 11), and the high-risk HPV types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) and grouped analyses were conducted for each category.

Risk of Sequential Infection.

The risk of sequential detection of a specific oral HPV infection type following that same HPV type at the genitals was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Univariate analyses, only, were carried out in individual HPV type analyses due to limited sample size. To this end, only grouped analyses were performed to assess the hazard of same-type sequential genital-oral infections in multivariate models. Demographic and sexual behavior variables were first evaluated in backward elimination stepwise models (p=0.20) for 9vHPV, low-risk HPV, high-risk HPV. Remaining covariates from each model were included in all final multivariate models to facilitate comparison of the impact from the same set of covariates on each outcome. Covariates also considered to be potential confounders for sequential genital to oral HPV infection, and not collinear, were included in all multivariable models.

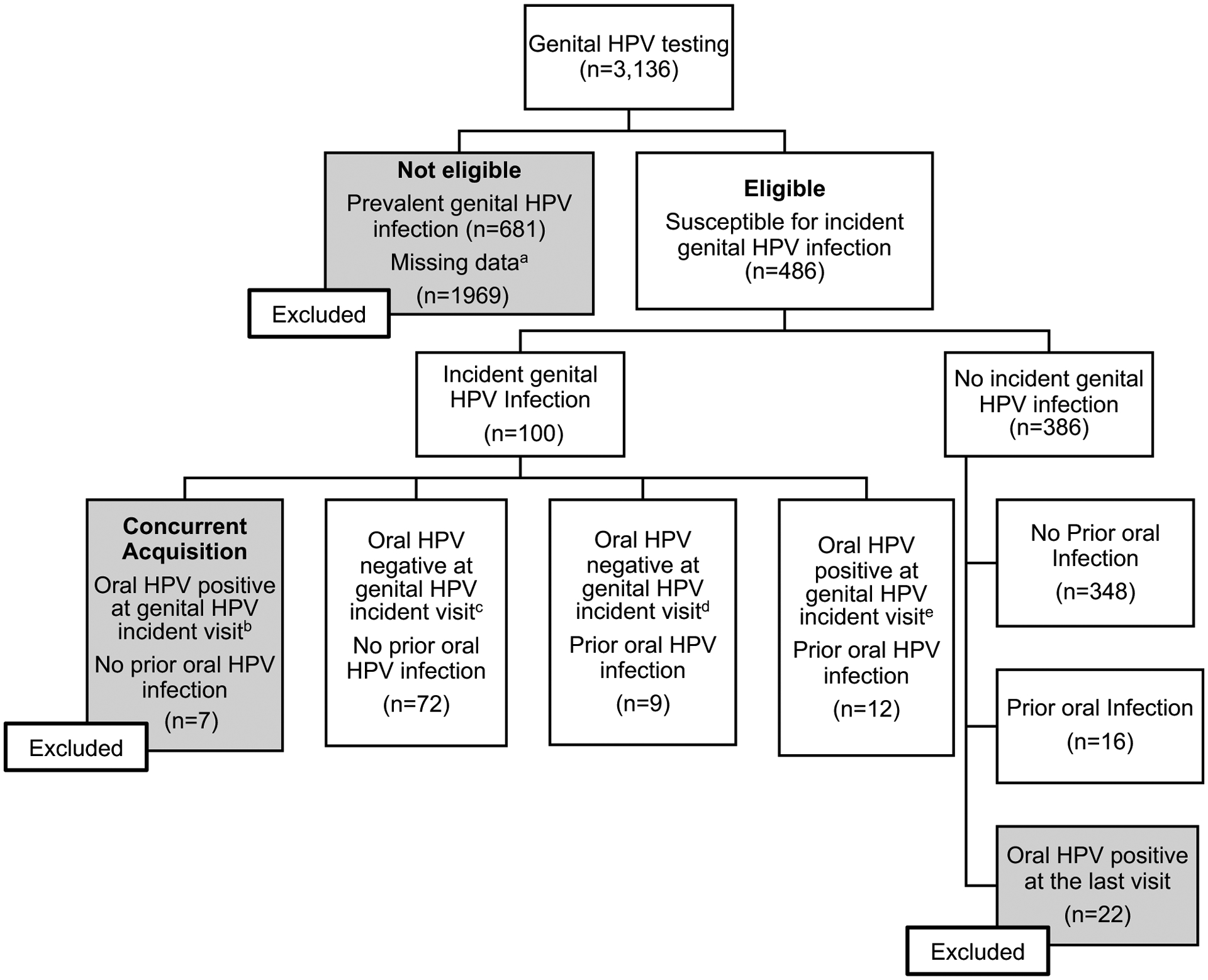

Risk of sequential genital infection.

To investigate the secondary aim of assessing risk of a sequential genital HPV infection following a prior, same-type oral HPV infection, the same selection criteria as above was applied to the study cohort. (Figure 2) In short, eligible subjects were assessed for incident genital HPV infection throughout follow-up and then categorized as either with or without prior oral HPV infection of the same type at the study visit just prior to the incident genital HPV positive visit or last visit with a genital HPV test (for subjects with no incident genital HPV infection). Then, to understand how sequential infection in this direction (oral-to-genital) compared to the genital-to-oral sequential infection above, the same covariates were used to build a multivariate model for grouped HPV analyses.

Figure 2.

Selection of study population from the HPV infection in Men (HIM) study for evaluation of sequential oral to genital HPV infection.

aPrevalent genital HPV infections (n=681). Missing data included subjects with No valid prior oral HPV test (n=1969).

bIncident genital and oral infections occurred at the same time and do not represent a sequential oral to genital infection. Subjects with concurrent infection excluded from sequential oral to genital analyses. The number of genital HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 2; HPV 11, 0; HPV 16, 1; HPV 18, 1; HPV 31, 0; HPV 33, 1; HPV 45, 1; HPV 52, 1; and HPV 58, 1. Number of men infected with multiple types of genital HPV: 1.

c The number of genital HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 15; HPV 11, 5; HPV 16, 17; HPV 18, 12; HPV 31, 7; HPV 33, 1; HPV 45, 8; HPV 52, 12; and HPV 58, 3. Number of men infected with multiple types or genital HPV: 7.

d The number of genital HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 4; HPV 11, 0; HPV 16, 1; HPV 18, 1; HPV 31, 0; HPV 33, 0; HPV 45, 3; HPV 52, 3; and HPV 58, 0. Number of men infected with multiple types or genital HPV: 2.

e The number of genital HPV-positive men according to each type was as follows: HPV 6, 2; HPV 11, 4; HPV 16, 2; HPV 18, 2; HPV 31, 1; HPV 33, 0; HPV 45, 1; HPV 52, 3; and HPV 58, 0. Number of men infected with multiple types or genital HPV: 3

Results

Risk of oral HPV infection after prior genital HPV infection

A total of 3,136 men had at least one genital and oral HPV DNA test (Figure 1). Of these men, 146 with prevalent oral HPV infection at their first oral gargle collection and 105 with missing data were excluded. Among 2,885 eligible subjects, 219 had an incident oral HPV infection. Of these men, 25 had evidence of concurrent acquisition of a genital and oral same type HPV infection and were also excluded from analyses; 124 were genital HPV negative at the time of the oral incident infection and at the visit prior to the incident oral infection. Among men with a prior genital infection 32 were genital HPV-negative for the same HPV type at the oral HPV-positive visit, and 38 were genital HPV-positive with the same HPV type at the oral HPV-positive visit.

Of those eligible for analysis, 2666 never acquired an oral HPV infection with one of the nine HPV types evaluated; and among these men, 493 had a prior genital infection at the visit just before the last study visit, while 1,988 did not. One hundred and eighty-five men who had a genital HPV infection detected at the last oral assessment study visit were excluded from analyses. (Figure 1)

The analyses of this study focused on comparing men by prior genital infection status. This included 563 men with a prior genital infection (493 with no incident oral HPV detected and 70 with an incident oral HPV infection) and 2,112 men without a prior genital infection (1,988 without an incident oral HPV infection and 124 with an incident oral HPV infection). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the men by prior genital infection status. These two groups differed significantly by country of residence, age, marital status, race, and sexual orientation. Men with a prior genital HPV infection were predominantly from Brazil (50.6%), white (51.1%), and more likely to have sex with men (5.4%) or be bisexual (8.7%). Men without a prior genital HPV infection were mostly married or cohabiting (54.1%), whereas men with a prior genital HPV infection were more often single (47.4%). Men with a prior genital HPV infection reported more alcoholic drinks (>60) consumed in the last 6 months (p<0.001), more lifetime number of sex partners (8–19 partners, and >19 partners) (p<0.001), more new partners (>2) in the last 6 months, more oral sex given (7–24 and >25 times) in the past 6 months (p<0.001), and more recently performing oral sex (0–3 days ago and 3–10 days ago) (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics Characteristics of Subjects, According to Prior Genital Infection with Any of the 9 Vaccine-Associated HPV Types, Among Subjects Negative for Oral HPV at Baseline

| Covariate | No Prior Genital Infectiona

N=2112 N (%) |

Prior Genital Infectionb

N=563 N (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of residence | US | 595 (28.2) | 146 (25.9) | <0.001 |

| Brazil | 764 (36.2) | 285 (50.6) | ||

| Mexico | 753 (35.7) | 132 (23.5) | ||

| Age | 18–30 | 877 (41.5) | 267 (47.4) | 0.041 |

| 31–44 | 883 (41.8) | 214 (38.0) | ||

| 45–73 | 352 (16.7) | 82 (14.6) | ||

| Marital Status | Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 160 (7.6) | 61 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 1133 (54.1) | 234 (41.7) | ||

| Single | 802 (38.3) | 266 (47.4) | ||

| Race | White | 907 (43.0) | 287 (51.1) | <0.001 |

| Black | 322 (15.3) | 110 (19.6) | ||

| Asian/PI | 52 (2.5) | 8 (1.4) | ||

| Othera | 802 (38.0) | 145 (25.8) | ||

| Refused | 27 (1.2) | 12 (2.1) | ||

| Education duration | Completed 12 Years or Less | 1007 (48.1) | 257 (46.0) | 0.644 |

| 13–15 Years | 486 (23.2) | 133 (23.8) | ||

| Completed at Least 16 Years | 599 (28.6) | 169 (30.2) | ||

| Number of Drinks of any Alcoholic Beverage Consumed in the Past One Month | 0 | 539 (25.9) | 104 (18.8) | <0.001 |

| 1–30 | 972 (46.6) | 241 (43.5) | ||

| 31–60 | 244 (11.7) | 63 (11.4) | ||

| >60 | 289 (13.9) | 131 (23.7) | ||

| Refused | 41 (2.0) | 15 (2.7) | ||

| Smoking status | Current | 415 (20.2) | 131 (23.9) | 0.149 |

| Former | 492 (23.9) | 139 (25.3) | ||

| Never | 1149 (55.8) | 278 (50.6) | ||

| Refused | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Circumcision | Not Circumcised | 1407 (66.6) | 361 (64.1) | 0.266 |

| Circumcised | 705 (33.4) | 202 (35.9) | ||

| Sexual Orientationb | MSW | 1684 (85.3) | 453 (83.6) | <0.001 |

| MSWM | 113 (5.7) | 47 (8.7) | ||

| MSM | 68 (3.4) | 29 (5.4) | ||

| Never had sex | 110 (5.6) | 13 (2.4) | ||

| Lifetime Number of Sex Partners | 0–2 | 584 (27.7) | 86 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| 3–7 | 596 (28.3) | 92 (16.4) | ||

| 8–19 | 479 (22.7) | 172 (30.7) | ||

| >19 | 438 (20.8) | 210 (37.4) | ||

| Refused | 11 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| New Partners in the Last Six Months | 0 | 498 (23.8) | 74 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 981 (46.9) | 204 (36.8) | ||

| >2 | 612 (29.3) | 277 (49.9) | ||

| Number of Times Gave Oral Sex in the past Six Months | 0 | 802 (39.2) | 156 (29.3) | <0.001 |

| 1–6 | 573 (28.0) | 152 (28.5) | ||

| 7–24 | 379 (18.5) | 123 (23.1) | ||

| >25 | 207 (10.1) | 72 (13.5) | ||

| Refused | 83 (4.1) | 30 (5.6) | ||

| Pack Years of Smoking | 0 | 1239 (58.7) | 303 (53.9) | 0.110 |

| 0–5 | 529 (25.1) | 153 (27.2) | ||

| >5 | 307 (14.5) | 99 (17.6) | ||

| Refused | 37 (1.8) | 7 (1.3) | ||

| Number of Teeth Lost Due to Oral Disease | 0 | 133 (79.6) | 46 (85.2) | 0.367 |

| >1 | 34 (20.4) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| Days since Last Gave Oral Sex | Never | 275 (13.5) | 32 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| 0–3 | 303 (14.9) | 100 (18.8) | ||

| >3–10 | 319 (15.7) | 101 (19.0) | ||

| 11–30 | 370 (18.2) | 109 (20.5) | ||

| >30 | 714 (35.1) | 177 (33.3) | ||

| Refused | 52 (2.6) | 12 (2.3) | ||

| Consistent Bleeding of Gums after Brushing | No | 152 (80.4) | 46 (79.3) | 0.853 |

| Yes | 37 (19.6) | 12 (20.7) | ||

Other race includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Asian/Pacific Islander, and mixed race

MSW: Men who have sex with women only; MSWM: Men who have sex with women and men; MSM: Men who have sex with men only; Never had sex: Never had oral, vaginal or anal sex during their lifetime

In grouped HPV type analyses, incidence of an oral HPV infection was significantly higher among men that had a prior, same-type genital infection with any of the 9-HPV vaccine types (9vHPV) (IRR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.5–2.6). Incidence of a high-risk oral HPV infection was 1.9 times higher among men with a prior high-risk genital HPV infection of the same type compared to men without a prior high-risk HPV infection (95% CI: 1.4–2.7), and 3.6 times higher for a low-risk HPV infection compared to men with no prior low-risk HPV infection of the same type (95% CI: 1.6–8.2). Oral HPV 16 incidence was significantly higher among men with a prior genital HPV 16 infection compared to men without a prior HPV 16 infection (IRR: 4.7; 95% CI: 2.5–8.8) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence Rate of Type-Specific Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection, by Prior Genital HPV Infection Status in the HPV Infection in Men Study

| No Prior Genital HPV Infectiona | Prior Genital HPV Infectionb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Type | Subjects at Risk, N | Incident Infections, N | Person-Months | Incidence per 1000 Person-Months (95% CI)a | Subjects at Risk, N | Incident Infections, N | Person-Months | Incidence per 1000 Person-Months (95% CI)a | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

| 9vHPVb | 2112 | 131 | 14293.20 | 9.59 (7.97, 11.53) | 563 | 73 | 4076.53 | 18.59 (14.54, 23.78) | 1.94 (1.45, 2.59) |

| Low Riskc | 2624 | 29 | 18035.33 | 1.08 (0.60, 1.93) | 160 | 7 | 1145.13 | 3.85 (1.61, 9.21) | 3.56 (1.55, 8.15) |

| High Riskd | 2260 | 131 | 15408.67 | 9.07 (7.55, 10.89) | 444 | 51 | 3161.97 | 17.62 (13.22, 23.49) | 1.94 (1.40, 2.69) |

| Type 6 | 2670 | 16 | 18395.70 | 0.71 (0.37, 1.35) | 125 | 5 | 871.50 | 4.40 (1.67, 11.65) | 6.24 (2.26, 17.17) |

| Type 11 | 2805 | 15 | 19361.03 | 0.44 (0.19, 1.01) | 36 | 2 | 279.07 | 2.83 (0.57, 13.97) | 6.43 (1.45, 28.38) |

| Type 16 | 2628 | 39 | 18109.27 | 2.26 (1.61, 3.17) | 170 | 13 | 1213.90 | 10.59 (5.89, 19.05) | 4.68 (2.48, 8.84) |

| Type 18 | 2762 | 15 | 19103.67 | 0.58 (0.29, 1.15) | 65 | 5 | 459.37 | 10.19 (3.81, 27.20) | 17.52 (6.24, 49.22) |

| Type 31 | 2797 | 17 | 19270.23 | 0.68 (0.32, 1.45) | 41 | 2 | 306.43 | 5.49 (1.22, 24.79) | 8.04 (1.84, 35.07) |

| Type 33 | 2828 | 9 | 19548.97 | 0.40 (0.17, 0.95) | 19 | 0 | 127.87 | 0.00 (NE) | NE |

| Type 45 | 2781 | 9 | 19181.07 | 0.51 (0.25, 1.03) | 45 | 1 | 318.87 | 3.83 (0.53, 27.74) | 7.50 (0.94, 59.94) |

| Type 52 | 2698 | 93 | 18530.97 | 4.84 (3.79, 6.19) | 113 | 6 | 850.20 | 6.62 (2.92, 15.02) | 1.37 (0.60, 3.13) |

| Type 58 | 2751 | 3 | 19026.27 | 0.17 (0.05, 0.57) | 76 | 1 | 553.63 | 1.77 (0.21, 15.14) | 10.41 (1.03, 105.42) |

Adjusted for country and age groups

Infections due to any of the 9 vaccine-type HPVs: 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

Infections due to HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

Infections due to HPV 6 and 11

The hazard ratio of a sequential genital to oral HPV infection of the same type in univariate analyses was 1.9 for any of the 9vHPV types (95% CI: 1.4–2.6); 1.9 for high-risk HPV types (95% CI: 1.–2.7); 3.3 for a low-risk HPV types (95% 1.4–8.0) (Table 3); and 5.4 for HPV 16 (95% CI: 2.9–10.2) (HPV16 data not shown). In multivariable models adjusting for age, country, circumcision, number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the past month, marital status, lifetime number of sex partners, and number of times oral sex given in the past 6 months minimal change from the crude hazard ratio was observed for all three outcomes (Table 3). Prior genital HPV infection of the same type was significantly associated with an oral HPV infection for any of the 9vHPV types (aHR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.2–2.4), high-risk HPV types (aHR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.4–2.7), and low-risk HPV types (aHR: 3.3; 95% CI: 1.4–8.0). Only age was also independently significantly associated with risk of an 9vHPV oral infection (p=0.020) or high-risk HPV oral infection (p=0.012), but not low-risk HPV oral infection (p=0.793). Number of alcohol drinks was marginally significantly associated with risk of a 9vHPV oral infection (p=0.050).

Table 3.

Risk of sequential acquisition of oral HPV following a genital HPV infection of the same type

| 9vHPVa N=2,073 |

High-Risk HPVb N=2,096 |

Low-Risk HPVc N=2,165 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Model | ||||

| Prior Genital Infection d | Yes | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | 3.3 (1.4, 8.0) |

| Adjusted Model | ||||

| Prior Genital Infection e | Yes | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) | 3.8 (1.5–9.5) |

| P prior genital | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005 | |

| Age | 18–30 | |||

| 31–44 | 1.5 (1.02–2.1) | 1.5 (0.98–2.2) | 1.3 (0.6–3.1) | |

| 45–73 | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) | 2.1 (1.3–3.5) | 1.2 (0.4–4.1) | |

| P age | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.793 | |

| Country | US | |||

| Brazil | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.6 (0.4–1.02) | 1.9 (0.7–5.4) | |

| Mexico | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.95 (0.2–3.9) | |

| P country | 0.251 | 0.117 | 0.319 | |

| Circumcision | Yes | |||

| No | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | |

| P circumcision | 0.089 | 0.124 | 0.139 | |

| Number of Alcoholic Drinks Consumed in the Past Month | 0 | |||

| 1–30 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | |

| 31–60 | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) | 1.03 (0.6–1.9) | 2.4 (0.8–7.1) | |

| >60 | 1.6 (0.97–2.6) | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | |

| Refused | 0.6 (0.07–4.5) | 0.7 (0.08–5.2) | NE | |

| P alcohol | 0.050 | 0.085 | 0.179 | |

| Lifetime Number of Sex Partners | 0–2 | |||

| 3–7 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.4 (0.1–2.0) | |

| 8–19 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.2 (0.04–1.2) | |

| >19 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.99 (0.3–3.7) | |

| Refused | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 0.6 (0.1–3.7) | |

| P sex partners | 0.402 | 0.665 | 0.164 | |

| Number of Times Gave Oral Sex in the past Six Months | 0 | |||

| 1–6 | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | 4.8 (1.1–21.6) | |

| 7–24 | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 5.0 (1.04–24.1) | |

| >25 | 1.6 (0.9–2.7) | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 4.0 (0.8–20.5) | |

| Refused | 2.0 (0.9–4.4) | 1.6 (0.7–3.6) | 9.0 (1.1–74.0) | |

| P oral sex | 0.075 | 0.226 | 0.255 | |

Abbreviations: HR: Hazard ratio; aHR: adjusted Hazard Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval

Bolded values indicate significance with p<0.05

Infections due to any of the 9 vaccine-type HPVs: 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

Infections due to HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

Infections due to HPV 6 and 11

Cox proportional Hazard Model: univariate analysis for risk of HPV infection by prior genital HPV infection status

Cox proportional Hazard Model adjusted for prior genital HPV infection status, age, country, circumcision, number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the past month, lifetime number of sex partners, and number of times oral sex was given in the past six months.

Risk of genital HPV infection after prior oral HPV infection

Of the same 3,136 men who had at least one oral and genital HPV test, there were many more removed for a prevalent genital HPV infection (n=894), missing data (n=1,969), or testing oral positive at the last visit (n=22). There were 100 subjects with an incident genital HPV infection and of those, 21 had a prior oral HPV infection of the same type. There were 386 subjects with no incident genital HPV infection and of those, 30 had a prior oral HPV infection. (Figure 2)

In univariate analyses, a prior oral HPV infection of the same type was significantly associated with a genital HPV infection for 9vHPV types (aHR: 3.4; 95% CI: 2.1–5.5), high-risk HPV types (aHR: 3.5; 95% CI: 2.0–6.1), and low-risk HPV types (aHR: 9.3; 95% CI: 3.6–23.9). When adjusting for age, country, circumcision, number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the past month, marital status, lifetime number of sex partners, and number of times oral sex given in the past 6 months minimal change from the crude hazard ratio for 9vHPV types (aHR: 3.5; 95% CI: 1.9–6.4), high-risk HPV types (aHR: 3.2; 95% CI: 1.6–6.4), and low-risk HPV types (aHR: 16.4; 95% CI: 4.2–65.1). Country (p=0.043) and lifetime number of sex partners (p=0.038) was independently significantly associated with a 9vHPV genital infection. Country was also independently significantly associated with a high-risk HPV genital infection (p=0.031). (Table 4)

Table 4.

Risk of sequential acquisition of genital HPV following an oral HPV infection of the same type

| 9vHPVa N=320 |

High-Risk HPVb N=342 |

Low-Risk HPVc N=391 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Model | ||||

| Prior Oral Infection d | Yes | 3.4 (2.1–5.5) | 3.5 (2.0–6.1) | 9.3 (3.6–23.9) |

| Adjusted Model | ||||

| Prior Oral Infection e | Yes | 3.5 (1.9–6.4) | 3.2 (1.6–6.4) | 16.4 (4.2–65.1) |

| P prior oral | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Age | 18–30 | |||

| 31–44 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.4 (0.2–0.99) | |

| 45–73 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | |

| P age | 0.496 | 0.478 | 0.115 | |

| Country | US | |||

| Brazil | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 2.4 (0.9–6.8) | |

| Mexico | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.7 (0.2–2.6) | |

| P country | 0.043 | 0.031 | 0.059 | |

| Circumcision | Yes | |||

| No | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 1.3 (0.70–2.3) | 1.4 (0.6–3.5) | |

| P circumcision | 0.331 | 0.436 | 0.467 | |

| Number of Alcoholic Drinks Consumed in the Past Month | 0 | |||

| 1–30 | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 1.01 (0.5–2.2) | 1.4 (0.4–4.5) | |

| 31–60 | 1.9 (0.8–4.2) | 2.0 (0.9–4.5) | 2.3 (0.6–8.1) | |

| >60 | 1.7 (0.8–3.5) | 1.3 (0.6–3.04) | 1.6 (0.5–5.5) | |

| Refused | 1.3 (0.3–6.4) | 1.5 (0.3–7.9) | 4.5 (0.4–51.0) | |

| P alcohol | 0.436 | 0.384 | 0.662 | |

| Lifetime Number of Sex Partners | 0–2 | |||

| 3–7 | ||||

| 8–19 | 2.1 (0.9–4.5) | 2.5 (1.2–5.4) | 1.9 (0.6–6.6) | |

| >19 | 2.7 (1.2–5.8) | 2.7 (1.2–6.2) | 3.9 (1.2–12.2) | |

| Refused | 3.9 (1.5–10.2) | 3.4 (1.1–10.5) | 2.6 (0.6–12.3) | |

| P sex partners | 0.038 | 0.060 | 0.121 | |

| Number of Times Gave Oral Sex in the past Six Months | 0 | |||

| 1–6 | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 1.02 (0.5–2.02) | 1.1 (0.4–3.01) | |

| 7–24 | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) | 1.4 (0.7–3.0) | 1.4 (0.5–3.9) | |

| >25 | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 1.4 (0.4–4.6) | |

| Refused | 1.2 (0.4–3.6) | 1.5 (0.5–4.8) | 0.9 (0.1–6.8) | |

| P oral sex | 0.612 | 0.852 | 0.952 | |

Abbreviations: HR: Hazard ratio; aHR: adjusted Hazard Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval

Bolded values indicate significance with p<0.05

Infections due to any of the 9 vaccine-type HPVs: 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

Infections due to HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

Infections due to HPV 6 and 11

Cox proportional Hazard Model: univariate analysis for risk of HPV infection by prior oral HPV infection status

Cox proportional Hazard Model adjusted for prior oral HPV infection status, age, country, circumcision, number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the past month, lifetime number of sex partners, and number of times oral sex was given in the past six months.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate oral HPV infection in men with or without a prior genital HPV infection of the same type. Overall, incidence of an oral HPV infection was significantly higher among men with a prior genital HPV infection of the same genotype. Specifically, prior genital infection with HPV 16, led to a >4-fold increase in the incidence of a subsequent oral infection with HPV 16, compared to men with no prior genital HPV 16 infection. A prior genital infection of the same type remained a key factor in the risk of an oral HPV infection with the hazard ratio changing minimally after adjustment for age, country, alcohol intake, lifetime number of sexual partners, circumcision, and number of times oral sex given in the past 6 months. In the opposite direction, the hazard of a sequential genital HPV infection after a prior oral HPV infection was even higher, and also changed minimally after adjustment for the same factors.

Incidence of HPV-associated OPC is increasing among males but not women and prevalence of oral HPV is higher among men than women.2, 3, 5 Sexual behavior factors are most strongly associated with oral HPV prevalence, but do not explain the prevalence completely.15 Our study provides the first indication that autoinoculation from the genitals may explain some of the excess risk of oral HPV infection observed in men, a phenomenon previously described in risk of anal HPV among men and women with prior genital infections but no evidence of anal sex.6–9 A study examining oral HPV prevalence by gender and concordance with genital HPV infections found that high-risk oral HPV was more prevalent in men than women, and oral HPV prevalence in men with a concurrent genital HPV infection was 4-fold greater than men without a concurrent genital HPV infection.16 Our prospective study observed similar patterns. We, however, excluded concurrent infections and limited analysis of presence of a prior genital infection to the same HPV type only, strengthening the evidence for genital to oral autoinoculation.

The hazard ratio of a sequential genital to oral HPV infection minimally changed after adjusting for key demographic and sexual behaviors known to be associated with oral HPV infection. We found age but not lifetime number of sexual partners to be significantly associated only with a 9vHPV or high-risk oral HPV infection, though both have been previously associated with oral HPV infections. Peak prevalence of oral HPV in men has been observed bimodally at age 30–34 and 60–645 but also linearly increasing with age, with peak prevalence among 55–74 year-olds.17 However, others have observed the effect of age diminished after adjusting for oral sex behaviors, including lifetime number of partners, concluding that oral sex behaviors are the primary predictor of risk of an oral HPV infection.18 Stability in marital status and fewer changes in sexual partners have been found to be protective against new genital and oral HPV infections.19 Our results support this for men with an incident genital HPV infection. When sequential infection was investigated in the opposite direction, lifetime number of sex partners was significantly associated with a 9vHPV genital infection after adjustment for the same key demographic and sex behavior variables. Further, we observed a prior oral HPV infection of the same type remained significantly associated with 9vHPV, high-risk, and low-risk genital HPV infection even after multivariable adjustment. However, in this model country, but not age, was significantly associated with a 9vHPV and high-risk HPV genital infection.

Overall, even after considering other known factors affecting risk of an oral HPV infection in men, a prior genital infection was a key factor for risk of a subsequent oral HPV infection of the same type. In all analyses, no other factors related to demographics, smoking, or sexual behavior altered the observed incidence or predicted risk of a subsequent oral HPV infection more than minimally. While this is the first study to report this finding among men, studies among women have similarly found a lack of data to support sexual transmission as the sole risk for oral HPV infection, suggesting autoinoculation of HPV from the anogenital region to oral cavity20. A concurrent cervical HPV infection was, alone, significantly associated with an oral HPV infection and detection of oral HPV further decreased with years since first sexual activity.21, 22

The importance of a genital HPV infection prior to detecting oral HPV and vice versa underscores the need for vaccination against HPV. Studies continue to show that HPV vaccination reduces the risk for cervical HPV in females.23 Further, protection against HPV at the oral cavity in males has now been observed via herd immunity from female-only vaccination programs, but also via direct vaccination in adolescent males. Prevalence of vaccine-type oral HPV is lower in both adult and adolescent males and females who have received an HPV vaccine.24–26 The results of our study further underscore the importance of adolescent vaccination to prevent oral and genital cancers. Oral sex is the most common sexual behavior in adolescents, and many are more likely to participate in oral sex before vaginal sex with the perception that it reduces sex-related risks such as STIs. Further, in older adolescents, oral sex has been found to be a protective factor for earlier vaginal sex initiation.27 With no evidence of vaccine-derived protection waning and efficacy shown to be at least 10 years28, vaccination in adolescence is especially important to first gain protection prior to exposure at any anatomical site and second, to sustain this protection through adulthood. Increasing rates of vaccination to prevent genital infection in men will likely lead to a decrease in prevalence of oral HPV, and thus HPV-associated OPC in men. Recent studies have also found an approximately five-fold increase in the risk of a second HPV-associated cancer at most sites following a primary HPV-associated invasive or pre-invasive tumor at the same or other sites29. For example, in men with a primary penile cancer the SIR for a secondary OPC diagnosis was 2.57 (95% CI: 0.81–5.32)29, 30 in one study and 4.57 (95% CI 2.54–8.85)29, 31 in another. This highlights the opportunity for vaccination through adulthood to not only prevent HPV-associated primary cancer but also secondary cancers.

To the best of our knowledge no other study has examined the risk of a type-specific sequential HPV infection between genital to oral sitesin men. Strengths of this study are a large sample size of men tested for both oral and genital HPV infections, a diverse cohort, and detailed survey data regarding oral HPV risk factors. These factors, which consist of demographics, smoking history, and sexual history including oral sex behaviors, were key to assessing HPV risk in study subjects. Further, standard HPV DNA extraction and genotyping methods were used for both genital and oral samples.

There are some limitations that need to be considered. Despite a large total sample size, individual HPV type sample sizes were small and assessment of risk factors by individual HPV type was, therefore, not possible for each HPV type. By conducting grouped HPV analyses with high- or low-risk types, we were able to discern differences in risk between HPV types with similar cancer risk. Detailed smoking and sexual history factors were adjusted in the models with minimal impact on overall risk of a sequential genital or oral HPV infection. It is possible that subjects may have had a genital/oral HPV infection that had cleared, or a latent genital/oral HPV infection present at the baseline visit and not detected until later follow-up visits. This is relatively unlikely in immunocompetent subjects such as those in the HIM study, though. Further, the HPV DNA extraction and identification methods utilized in this study can detect a low viral load of HPV, limiting the possibility of an undetected latent l HPV infection. A final consideration is the assessment of multiple HPV infections at both sites and over time. Due to very few oral HPV infections with multiple HPV types, they were not considered and would likely not alter the rates or risk of developing a sequential infection. Instead, by focusing on type-specific HPV infections occurring within sequential study visits with adjustment for confounders such as recent sexual behaviors, we feel the results better test the hypothesis that sequential acquisition of oral HPV after a genital HPV infection and vice versa may be due to self-inoculation. With a study population from three countries with diverse socioeconomic status and demographics who were followed longitudinally over several years, these results are highly generalizable to many men with similar backgrounds. However, future studies should investigate the generalizability of these results in other populations including high-risk groups such as men living with HIV, or other men from high resource countries where OPC rates are increasing.

In conclusion, incidence of an oral HPV infection was higher among those with a prior genital HPV infection of the same type compared to men without a prior genital HPV infection and specifically, >4-fold higher for HPV 16 alone. A prior genital HPV infection of the same type was an important risk factor for a sequential oral HPV infection of the same HPV type, even after adjusting for other known oral HPV risk factors. Alternatively, the risk of a genital infection after a prior oral HPV infection of the same was even higher, with prior oral infection also the key risk factor. These findings emphasize the importance of primary prevention of HPV infection through vaccination. This, in turn, would also prevent subsequent HPV infections at different anatomical sites and likely reduce the rising rates of OPC as well as other HPV-associated cancer in men.

Novelty & Impact:

This study found that when adjusting for other relevant factors, a prior genital HPV infection was the predominant risk factor for an oral HPV infection of the same HPV genotype. This was also true for a genital HPV infection after a prior same-type oral HPV infection. These results highlight the importance of HPV vaccination to prevent HPV infections at all sites and address the increasing rates of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer among men in the U.S.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Robert S. Evans and the R.S. Evans Foundation for supporting this work. We also thank the HIM Study teams and participants in the United States (Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa), Brazil (Centro de Referência e Treinamento em DST/AIDS, Fundação Faculdade de Medicina Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo), and Mexico (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01 CA214588] and the R.S. Evans Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Giuliano reports grants from Merck & Co, personal fees from Merck & Co outside the submitted work. Dr. Villa is an occasional speaker for HPV prophylactic vaccines of Merck, Sharp & Dohme.

Abbreviations:

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- OPC

Oropharyngeal cancer

- STI

Sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

All participants gave written informed consent prior to study participation.

Approval was obtained from the human subjects committees of the University of South Florida (United States), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Brazil), Centro de Referencia e Treinamento em Doencas Sexualmente Transmissíveis e AIDS (Brazil), and Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica de Mexico (Mexico).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, some access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. Data are available to outside investigators but within the limitations of preserving the anonymity of individuals since these data could theoretically identify a study participant and contain sensitive information. All reasonable data requests should be directed to the Center for Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, 33612 (email: ciirc@moffitt.org).

References

- 1.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2000;92:709–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Rosenberg PS, Bray F, Gillison ML. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Journal of clinical oncology 2013;31:4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, Jiang B, Goodman MT, Sibug-Saber M, Cozen W. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology 2011;29:4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone A-M, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, Eheman C, Saraiya M, Bandi P, Saslow D. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2013;105:175–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong Z-y, Xiao W, Kahle L, Graubard BI, Chaturvedi AK. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. Jama 2012;307:693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman MT, Shvetsov YB, McDuffie K, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, Thompson PJ, Ning L, Killeen J, Kamemoto L, Hernandez BY. Sequential acquisition of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the anus and cervix: the Hawaii HPV Cohort Study. The Journal of infectious diseases 2010;201:1331–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guler T, Uygur D, Uncu M, Yayci E, Atacag T, Bas K, Gunay M, Yakicier C. Coexisting anal human papilloma virus infection in heterosexual women with cervical HPV infection. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 2013;288:667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez BY, McDuffie K, Zhu X, Wilkens LR, Killeen J, Kessel B, Wakabayashi MT, Bertram CC, Easa D, Ning L. Anal human papillomavirus infection in women and its relationship with cervical infection. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 2005;14:2550–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pamnani SJ, Nyitray AG, Abrahamsen M, Rollison DE, Villa LL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Huang Y, Borenstein A, Giuliano AR. Sequential Acquisition of Anal Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection Following Genital Infection Among Men Who Have Sex With Women: The HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. J Infect Dis 2016;214:1180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, Flores R, Salmeron J, Lee JH, Papenfuss MR, Abrahamsen M, Jolles E, Nielson CM, Baggio ML, Silva R, et al. The human papillomavirus infection in men study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2008;17:2036–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giuliano AR, Lee J-H, Fulp W, Villa LL, Lazcano E, Papenfuss MR, Abrahamsen M, Salmeron J, Anic GM, Rollison DE. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. The Lancet 2011;377:932–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. The Lancet. Oncology; 2009;10:321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleter B, Van Doorn L-J, Schrauwen L, Molijn A, Sastrowijoto S, ter Schegget J, Lindeman J, ter Harmsel B, Burger M, Quint W. Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. Journal of clinical microbiology 1999;37:2508–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Gomez L, Giuliano AR, Fulp WJ, Caudell J, Echevarria M, Sirak B, Abrahamsen M, Isaacs-Soriano KA, Hernandez-Prera JC, Wenig BM. Human papillomavirus genotype detection in oral gargle samples among men with newly diagnosed oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2019;145:460–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases 2009;199:1263–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonawane K, Suk R, Chiao EY, Chhatwal J, Qiu P, Wilkin T, Nyitray AG, Sikora AG, Deshmukh AA. Oral human papillomavirus infection: differences in prevalence between sexes and concordance with genital human papillomavirus infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Annals of internal medicine 2017;167:714–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreimer AR, Villa A, Nyitray AG, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss M, Smith D, Hildesheim A, Villa LL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Giuliano AR. The epidemiology of oral HPV infection among a multinational sample of healthy men. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 2011;20:172–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Souza G, Cullen K, Bowie J, Thorpe R, Fakhry C. Differences in oral sexual behaviors by gender, age, and race explain observed differences in prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection. PloS one 2014;9:e86023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kero K, Rautava J, Syrjänen K, Kortekangas-Savolainen O, Grenman S, Syrjänen S. Stable marital relationship protects men from oral and genital HPV infections. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases 2014;33:1211–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlecht NF, Masika M, Diaz A, Nucci-Sack A, Salandy A, Pickering S, Strickler HD, Shankar V, Burk RD. Risk of oral human papillomavirus infection among sexually active female adolescents receiving the quadrivalent vaccine. JAMA network open 2019;2:e1914031–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eggersmann T, Sharaf K, Baumeister P, Thaler C, Dannecker C, Jeschke U, Mahner S, Weyerstahl K, Weyerstahl T, Bergauer F. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in cervical HPV positive women and their sexual partners. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2019;299:1659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabeena S, Bhat P, Kamath V, Arunkumar G. Possible non‐sexual modes of transmission of human papilloma virus. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2017;43:429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlecht NF, Burk RD, Nucci-Sack A, Shankar V, Peake K, Lorde-Rollins E, Porter R, Linares LO, Rojas M, Strickler HD. Cervical, anal and oral HPV in an adolescent inner-city health clinic providing free vaccinations. PloS one 2012;7:e37419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castillo A, Osorio JC, Fernández A, Méndez F, Alarcón L, Arturo G, Herrero R, Bravo LE. Effect of vaccination against oral HPV-16 infection in high school students in the city of Cali, Colombia. Papillomavirus Research 2019;7:112–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirth JM, Chang M, Resto VA, Guo F, Berenson AB. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus by vaccination status among young adults (18–30 years old). Vaccine 2017;35:3446–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehanna H, Bryant TS, Babrah J, Louie K, Bryant JL, Spruce RJ, Batis N, Olaleye O, Jones J, Struijk L. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine effectiveness and potential herd immunity for reducing oncogenic oropharyngeal HPV-16 prevalence in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019;69:1296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song AV, Halpern-Felsher BL. Predictive relationship between adolescent oral and vaginal sex: Results from a prospective, longitudinal study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 2011;165:243–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brotherton JM, Bloem PN. Population-based HPV vaccination programmes are safe and effective: 2017 update and the impetus for achieving better global coverage. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology 2018;47:42–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert DC, Wakeham K, Langley RE, Vale CL. Increased risk of second cancers at sites associated with HPV after a prior HPV-associated malignancy, a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of cancer 2019;120:256–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemminki K, Jiang Y, Dong C. Second primary cancers after anogenital, skin, oral, esophageal and rectal cancers: etiological links? International journal of cancer 2001;93:294–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sikora AG, Morris LG, Sturgis EM. Bidirectional association of anogenital and oral cavity/pharyngeal carcinomas in men. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2009;135:402–05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, some access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. Data are available to outside investigators but within the limitations of preserving the anonymity of individuals since these data could theoretically identify a study participant and contain sensitive information. All reasonable data requests should be directed to the Center for Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, 33612 (email: ciirc@moffitt.org).