Abstract

Background

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMP) family proteins are peptidases involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation. Various diseases are related to TIMPs, and the primary reason is that TIMPs can indirectly regulate remodelling of the ECM and cell signalling by regulating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity. However, the link between TIMPs and glioblastoma (GBM) is unclear.

Objective

This study aimed to explore the role of TIMP expression and immune infiltration in GBM.

Methods

Oncomine, GEPIA, OSgbm, LinkedOmics, STRING, GeneMANIA, Enrichr, and TIMER were used to conduct differential expression, prognosis, and immune infiltration analyses of TIMPs in GBM.

Results

All members of the TIMP family had significantly higher expression levels in GBM. High TIMP3 expression correlated with better overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in GBM patients. TIMP4 was associated with a long OS in GBM patients. We found a positive relationship between TIMP3 and TIMP4, identifying gene sets with similar or opposite expression directions to those in GBM patients. TIMPs and associated genes are mainly associated with extracellular matrix organization and involve proteoglycan pathways in cancer. The expression levels of TIMPs in GBM correlate with the infiltration of various immune cells, including CD4+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, B cells, CD8+ T cells, and dendritic cells.

Conclusions

Our study inspires new ideas for the role of TIMPs in GBM and provides new directions for multiple treatment modalities, including immunotherapy, in GBM.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12883-021-02477-1.

Keywords: Bioinformatics analysis, Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases family, Glioblastoma, Biomarker, Prognosis, Immune infiltration

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive of the four grades of gliomas classified by WHO [1] and accounts for 17% of all primary brain tumours [2]. When radiotherapy was combined with temozolomide, the survival time of GBM patients reached 14.6 months, and the 2-year OS and 5-year OS rates were 27.2 and 9.8%, respectively [3]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases implicated in degrading components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [4], tumour cell invasion and angiogenesis, and suppression of antitumour immune surveillance [5]. Previous studies have found that MMPs are associated with different tumour types, such as papillary thyroid carcinomas [6] and lung adenocarcinoma [7]. Several studies have indicated that MMPs are related to increased invasiveness [8] and a poor prognosis [9] in GBM. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) comprise four natural endogenous secreted proteins that inhibit the activity of MMPs [10]. Therefore, TIMPs regulate cellular processes such as migration, proliferation, and survival by controlling ECM degradation via interaction with MMPs [11]. In addition to this originally described feature [12], over the past decade, many additional relatively independent biological activities have been identified, including cell growth [13], apoptosis [14], differentiation [15], angiogenesis [16], and proliferation [17].

The TIMP gene family has been studied in various tumours, including GBM, but no systematic analysis has investigated the relationship between their expression and prognosis in glioblastoma. With the development of microarray technology, immune infiltration research, and the progress of single-cell technology, using bioinformatics analysis is vital to examine the expression pattern and prognostic value of the TIMP gene family in glioblastoma and to use cutting-edge technology and related research data for further analysis. This process will also lead to an update of our understanding of this ancient family.

Materials and methods

Oncomine

Oncomine (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html) is a platform with powerful analysis functions that compute gene expression signatures, clusters, and gene-set modules from the data [18]. We analysed the mRNA expression of TIMPs and compared the difference between the normal and tumour groups by Student’s t-test in various tumours on this platform. A p value < 0.05 and fold change ≥2 for the p value indicated that the difference between the normal and tumour groups was statistically significant.

GEPIA2

GEPIA2 (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) is an updated version of Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) that processes mRNA data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) projects [19]. The website has various customized functions, such as similar genetic testing, correlation analysis, and dimensionality reduction analysis. In our study, we performed differential expression analysis of family genes as a validation set.

OSgbm

OSgbm (http://bioinfo.henu.edu.cn/GBM/GBMList.jsp.) is a web server that performs online survival analysis of glioblastoma [20]. This website comprises 684 samples with transcriptome profiles and clinical information from TCGA, Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA). We used it to explore the impact of TIMPs on the prognosis of GBM patients. The survival analysis results are presented as Kaplan–Meier (KM) plots with hazard ratios (HRs) and log-rank plots with p values.

LinkedOmics

LinkedOmics (http://www.linkedomics.orglogin.php) is a public portal for multiomics data that mainly includes TCGA cancer types [21]. The mutual combination of different modules allows the analysis of multiomics data from various cancers. Here, we explored the expression relationships between TIMPs and different genes in GBM.

Gliovis

Gliovis (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/) is a user-friendly website tool that includes brain tumour research results containing more than 6,500 tumour samples, approximately 50 expression datasets, and mainly gliomas [22]. We explored GBM data from the TCGA database at this server to investigate the correlation between the expression of TIMP family gene members and GBM subgroups according to different classifications.

STRING

STRING (https://string-db.org/) is a website to perform protein interactions. Its goal is to build a comprehensive, objective global network that can perform direct (physical) and indirect (functional) interactions of proteins. We used it to generate protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks of TIMPs.

GeneMANIA

GeneMANIA (https://genemania.org/) is a server that performs gene association and similar gene exploration [23]. It can extend the submitted gene list by analysing a large amount of association data in the background and the gene association function in the list. We found the associated genes of TIMPs here and explored their different functions with GeneMANIA.

Enrichr

Enrichr (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/) is a search engine that performs multiple functional enrichment analyses of input genes by querying many collections of annotated genes [24–26]. We performed functional analysis here for the set of genes generated in GeneMANIA.

cBioPortal

cBioPortal (http://cbioportal.org) is an open portal to explore and analyse multidimensional data from different cancers and combine molecular data and clinical data with visualization. We used this database to explore the mutation of TIMP family genes in GBM and link them to prognosis.

TIMER

TIMER (http://timer.cistrome.org/) is a user-friendly portal that evaluates the molecular characterization of tumour interactions with immunity [27]. It calculates the level of immunity in various infiltrating tumours in advance and provides six main analysis modules so that the relationship between tumours and immunity can be interactively explored. We conducted a correlative analysis of TIMPs at this site for measures of immune infiltration, including tumour purity and six immune cells in GBM.

Results

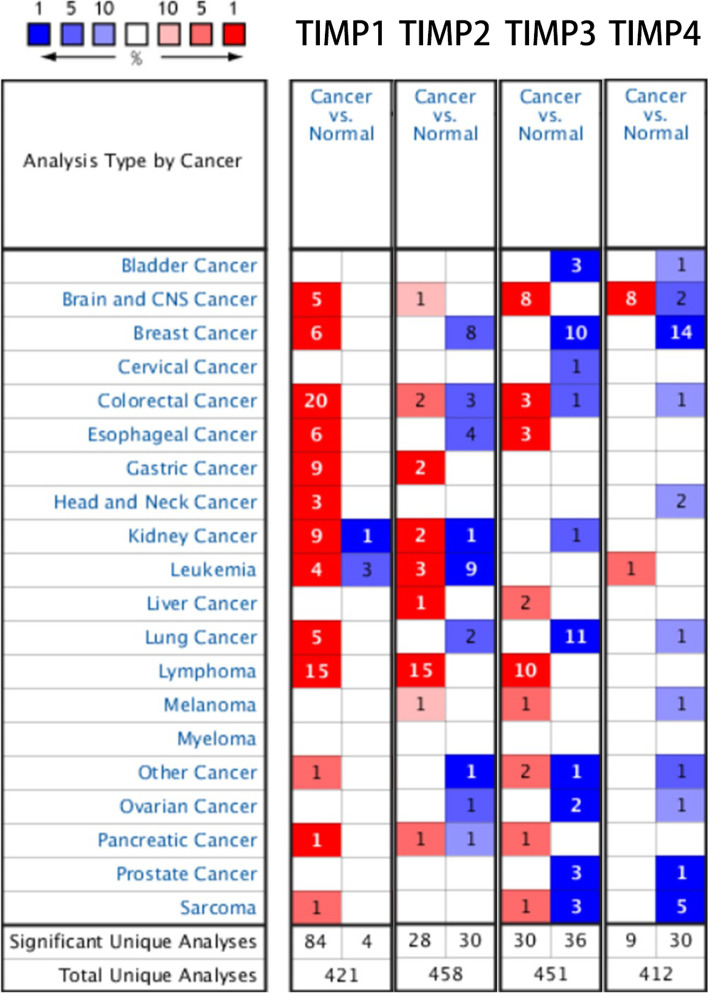

Transcriptional levels of TIMPs in patients with GBM

Four TIMP factors have been identified in humans. We compared the transcriptional levels of TIMPs in GBM with those in normal samples using the filter of differential analysis in Glioblastoma vs. Normal and Brain Glioblastoma vs. Normal in ONCOMINE databases (Fig. 1). The mRNA expression levels of TIMP1 were significantly upregulated in patients with GBM in five datasets (Table 1). In detail, the expression level of TIMP1 in the tumour group was dramatically augmented with a fold change of 18.922 in Bredel Brain 2’s dataset [28]. Additionally, the lowest fold change of 2.419 was found in the differential comparison between GBM and normal samples of neural stem cells in Lee Brain’s dataset [29]. Regarding TIMP2, increased expression occurred in both TCGA Brain and Liang Brain [30] datasets (Table 1). The samples of these two datasets were brain vs. brain GBM, brain and cerebellum vs. GBM. The fold change of TIMP2 in TCGA Brain was 2.218, and the latter was 2.304. In Bredel Brain 2’s [28] and Lee Brain’s datasets [29], TIMP3 was overexpressed with a fold change≥2 (Table 1). TIMP4 was overexpressed in two types of samples in the TCGA Brain’s dataset: brain GBM vs. brain and GBM vs. brain. Their fold changes, 8.998 and 8.887, respectively, were both higher (Table 1). The lowest fold change of 2.774 appeared in Shai Brain’s dataset [31], and the sample of this dataset was GBM vs. White Matter.

Fig. 1.

mRNA expression of TIMP family members in different cancers

Table 1.

Significant changes in TIMP expression at the transcription level between different types of GBM and normal tissues (oncomine)

| Gene ID | p Value 1 | Fold change | p Value 2 | t test | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIMP-1 | 8.87E-7 | 6.899 | 6.76E-14 | 12.843 | GBM vs. Brain and Cerebellum | Liang Brain |

| 18.922 | 9.53E-13 | 12.271 | GBM vs. Brain | Bredel Brain 2 | ||

| 4.55 | 1.06E-7 | 6.588 | GBM vs. White Matter | Shai Brain | ||

| 2.419 | 1.65E-6 | 6.096 | GBM vs. Neural Stem Cell | Lee Brain | ||

| 5.188 | 1.24E-11 | 8.438 | GBM vs. Brain | Sun Brain | ||

| TIMP2 | 0.006 | 2.218 | 6.09E-9 | 14.400 | Brain GBM vs. Brain | TCGA Brain |

| 2.304 | 0.012 | 4.418 | GBM vs. Brain and Cerebellum | Liang Brain | ||

| TIMP3 | 1.16E-5 | 9.042 | 1.48E-10 | 13.731 | GBM vs. Neural Stem Cell | Lee Brain |

| 2.008 | 4.39E-8 | 8.106 | GBM vs. Brain | Bredel Brain 2 | ||

| TIMP4 | 2.33E-4 | 4.168 | 1.93E-13 | 12.220 | GBM vs. Brain | Murat Brain [32] |

| 7.897 | 3.86E-19 | 11.720 | GBM vs. Brain | Sun Brain [33] | ||

| 8.998 | 4.50E-4 | 6.316 | GBM vs. Brain | TCGA Brain | ||

| 8.887 | 4.95E-9 | 14.307 | Brain GBM vs. Brain | TCGA Brain | ||

| 2.774 | 1.51E-5 | 4.948 | GBM vs. White Matter | Shai Brain |

p Value 1: p Value in comparison across gene analyses

p Value 2: p Value in a gene analysis

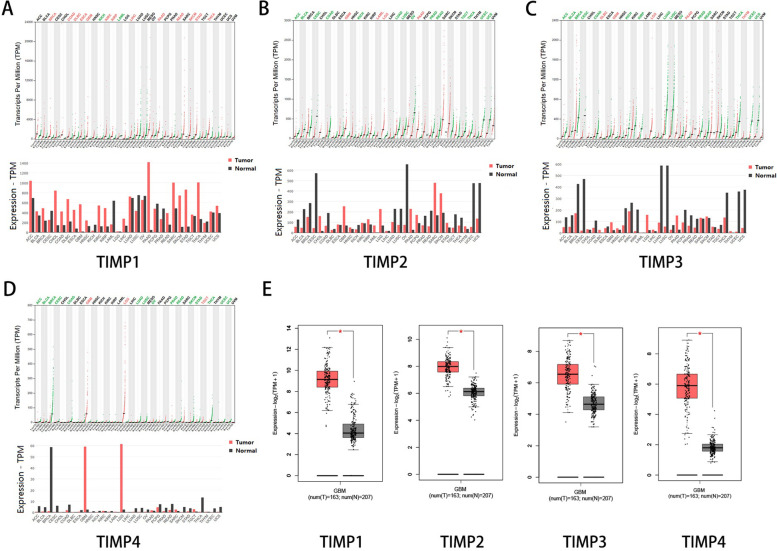

Differential expression of TIMPs in GBM

In the GEPIA (Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis) dataset (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), we compared the mRNA expression level of TIMPs between GBM and normal samples. The gene expression levels of TIMP1, TIMP2, TIMP3, and TIMP4 were all higher in GBM than in normal samples (Fig. 2A–E).

Fig. 2.

Expression of TIMPs in GEPIA2. TIMP1 expression in pan-cancer (A). TIMP2 expression in pan-cancer (B). TIMP3 expression in pan-cancer (C). TIMP4 expression in pan-cancer (D). Differential expression of TIMPs between GBM and normal samples (E). *: p<0.05

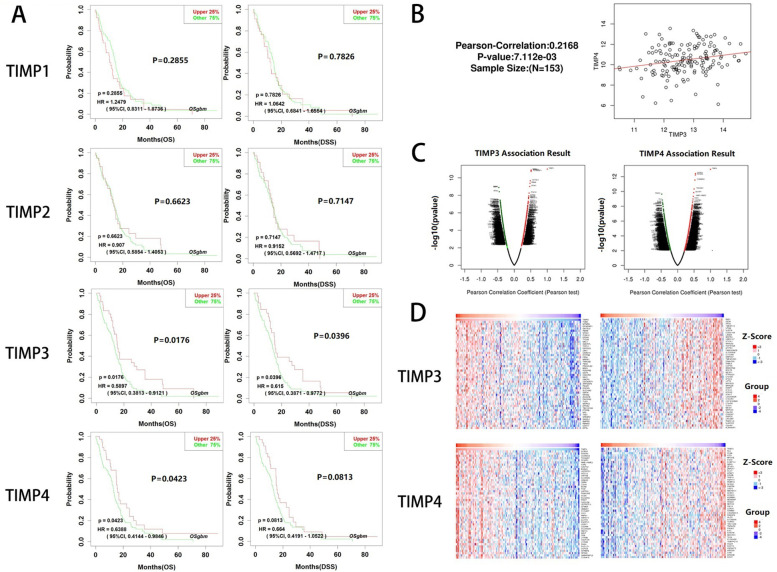

The prognostic values of TIMPs in glioblastoma and co-expression genes of significant gene

We investigated the prognostic value of TIMP1, TIMP2, TIMP3 and TIMP4 in GBM data from TCGA using OSgbm [20]. The TIMP3 overexpression group was associated with better overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) (Fig. 3A). TIMP4 overexpression was associated with better OS but without significance in DSS (Fig. 3A). Neither TIMP1 nor TIMP2 showed differences in OS and DSS (Fig. 3A). Next, we found a positive correlation between TIMP3 and TIMP4 expression in the LinkedOmics dataset (R = 0.2168, p <0.01) (Fig. 3B) [21].

Fig. 3.

Prognostic value and related genes of TIMPs in GBM. Prognostic value of TIMPs in GBM (A). Correlation of TIMP3 and TIMP4 (B). Volcano plot of genes implicated in the expression of TIMP3 and TIMP4 in GBM (C). Heatmap of the top 50 genes positively and negatively correlated with the expression of TIMP3 and TIMP4 in GBM (D)

Given the prognostic value of TIMP3 and TIMP4, using the functional module of LinkedOmics, we explored their associated genes in the TCGA_GBM cohort. The genes positively (dark red dots) and negatively (dark green dots) correlated with TIMP3 and TIMP4 are shown in Fig. 3C. The top 50 significant genes positively and negatively correlated with TIMP3 and TIMP4 are shown in the heat map (Fig. 3D). TIMP3 expression showed a positive association with the expression of TOB2 (positive rank #1; r = 0.513; p = 1.275e-11), MTMR3 (r = 0.511; p = 1.448e-11), and EIF4ENIF1 (r = 0.510; p = 1.832e-11). The top three genes with a positive correlation with TIMP4 were SCRG1 (r = 0.544; p = 3.778e-13), SHISA4 (r = 0.540; p = 5.826e-13) and COMMD2 (r = 0.526; p = 2.890e-12). These genes are more likely to be protective genes similar to TIMP3 and TIMP4.

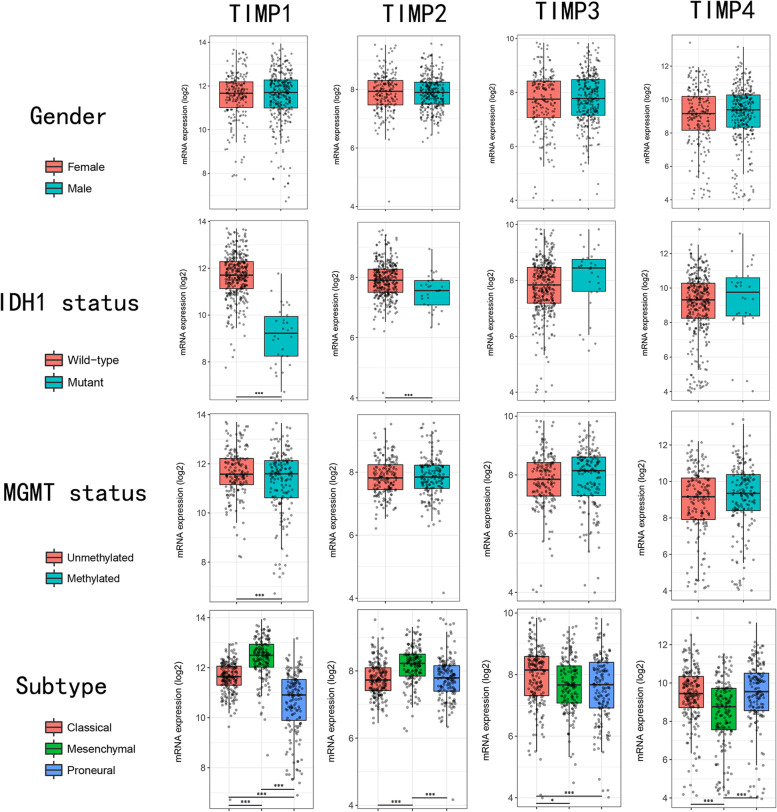

Validation of the expression of TIMPs in different subgroups of GBM

We divided the GBM data from TCGA into different subgroups according to different criteria in Gliovis. Next, we investigated whether TIMPs were differentially expressed between different subgroups (Fig. 4). The four TIMP family members were not differentially expressed between sexes.

Fig. 4.

Correlations of TIMPS with subgroups. The expression data of TIMPs in GBM from TCGA were grouped according to sex, IDH1 status, MGMT status, and subtype. The correlation was verified using T-test. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05

The expression levels of both TIMP1 and TIMP2 were significantly decreased in patients with IDH1 mutations. However, no association was found between TIMP3 and TIMP4 expression and IDH1 mutation. Among the TIMP family, only TIMP1 expression correlated with methylation of the MGMT promoter. We focused on evaluating the differential expression of TIMPs between different subtypes of GBM. The four genes showed significant expression differences among classical, mesenchymal and proneural GBM. TIMP1 and TIMP2 expression was highest in the mesenchymal region, but TIMP3 and TIMP4 expression lower in this region. Specific data can be viewed in the Supplementary file.

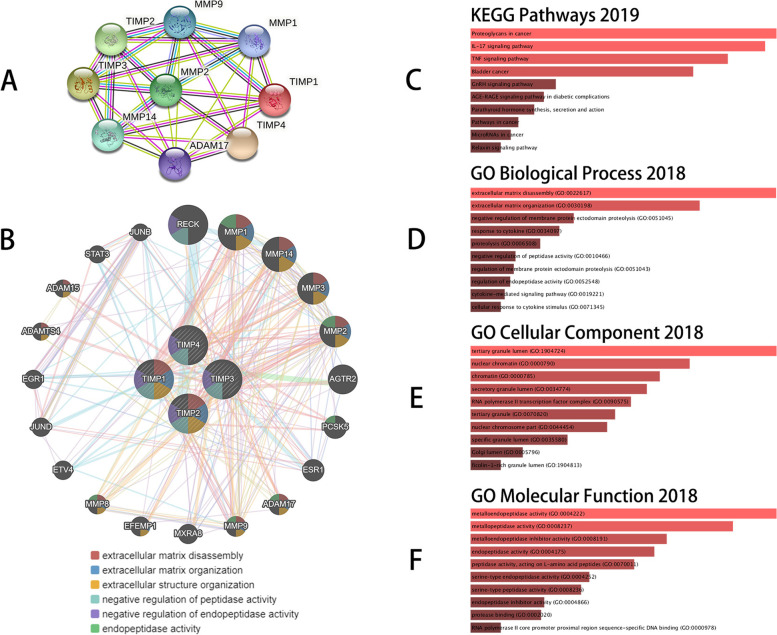

Protein-protein interaction analyses and functional enrichment analysis of TIMPs

We performed protein–protein interaction PPI network analysis of TIMPs using STRING to explore the potential interactions among them. Eventually, we obtained a protein interaction network comprising 9 nodes and 29 edges (Fig. 5A). We also used the GeneMANIA database to identify the genes associated with TIMPs, revealing that the functions of TIMPs with 20 related molecules (such as RECK, MMP1, MMP14, MMP3, MMP2, AGTR2, and PCSK5) were primarily associated with extracellular matrix organization, extracellular structure organization, negative regulation of peptidase activity and endopeptidase activity (Fig. 5B). To further analyze the functions of TIMPs and related genes as well as to make a comparative control with the functions presented on GeneMANIA, we performed functional enrichment analysis of these genes at the Enrichr website. The results showed that the top 10 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways for TIMPs and their 20 correlated genes were mainly associated with proteoglycans in cancer, the IL-17 signalling pathway, the TNF signalling pathway, the GnRH signalling pathway, and others (Fig. 5C) [34]. These pathways may involve mechanisms of progression in GBM. Next, using the Enrichr tool, GO analysis was performed using TIMPs and their correlated genes to analyse functions in biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. TIMPs and correlated genes were mainly associated with extracellular matrix disassembly in biological processes (Fig. 5D), tertiary granule lumen in cellular components (Fig. 5E), and metalloendopeptidase activity in molecular functions (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Interaction analysis and functional enrichment analysis of TIMPs. PPI network of TIMPs including 9 nodes and 29 edges (STRING) (A). Gene–gene interaction network of TIMPs (GeneMANIA) (B). Functional enrichment analysis of TIMPs and related genes in patients with GBM (C-F)

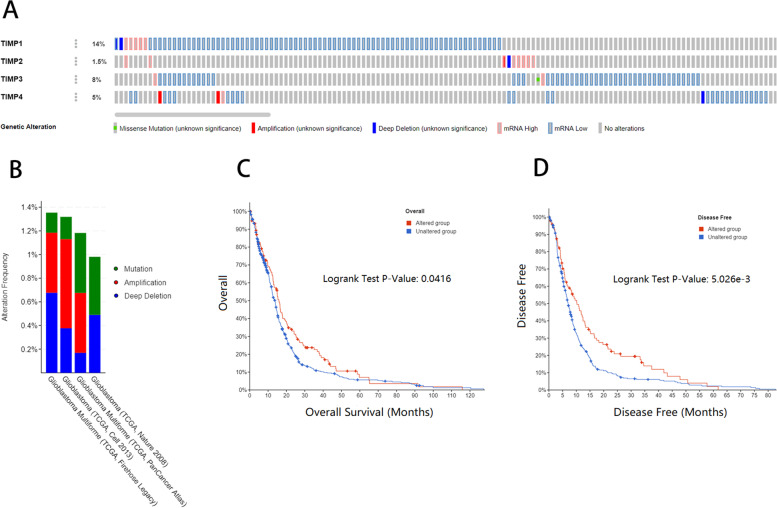

Genetic alteration of TIMPs in patients with GBM

We analysed the genetic changes of TIMPs in the database. The TIMP gene was genetically altered in 23% of cases. The alteration frequency was 14% for TIMP1, 1.5% for TIMP2, 8% for TIMP3 and 5% for TIMP4 (Fig. 6A). However, these data primarily represent expression changes. We explored the mutation status of TIMPs in the four databases Glioblastoma (TCGA, Nature 2008), Glioblastoma Multiforme (TCGA, Firehose Legacy), Glioblastoma Multiforme (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas) and Glioblastoma (TCGA, Cell 2013) and found that the highest mutation frequency did not exceed 1.4% (Fig. 6B). We also performed correlation analysis between patients with genetic alterations in TIMPs and prognostic conditions in the database and found that the patients were significantly associated with better OS and DFS (Fig. 6C, D).

Fig. 6.

Genetic alterations linked to hub genes in THCA. Alteration frequencies of TIMPs (A). Genetic mutations frequencies of TIMPs in GBM (B). KM plots comparing OS in patients with and without TIMP alterations (C). KM plots comparing DFS in patients with and without TIMP alterations (D)

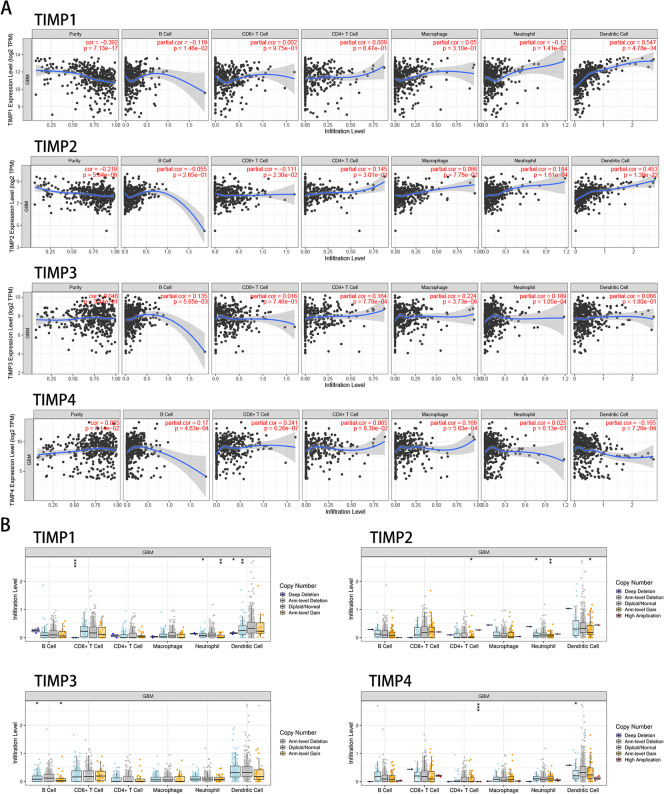

Relationship between TIMPs expression and immune infiltration in GBM

Immune infiltration is a component of the tumour microenvironment and is highly correlated with the diagnosis, progression, and prognosis of tumours. We used the TIMER database in this study to reveal the correlation between the gene expression levels of TIMP family members and immune cell infiltration in patients with GBM (Fig. 7A). TIMP1 expression was negatively associated with tumour purity but positively correlated with dendritic cells. Additionally, this correlation was also observed for TIMP2. TIMP3 expression was associated with B cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. However, no negative results are shown for TIMP3. Finally, TIMP4 expression was positively associated with the infiltration of B cells, CD8+ T cells, and macrophages in GBM patients. We also explored the relationship between the copy number variation (CNV) of TIMPs and immune infiltration level (Fig. 7B). The association of CNV with immune infiltration varied among the four genes. The levels of CNS in TIMP1 and TIMP2 were associated with more immune infiltration indicators, and , their arm-level deletion and arm-level gain were closely related to neutrophils. Regarding the remaining two genes, TIMP3 and TIMP4, that affected the prognosis, the CNV level of TIMP3 was the least significantly associated with immune infiltration indicators but was the only member of the family whose CNV affected the immune infiltration level of B cells. The CNV of TIMP4 was significantly correlated with both CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells, a finding similar to that of TIMP2. However, the CNV showed no correlation with neutrophils.

Fig. 7.

Association of the genetic expression of TIMPs with immune infiltration in GBM. Correlation between the abundance of immune cells and expression of TIMPs (A). Effect of the CNV of TIMPs on the distribution of various immune cells (B). (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

Previous studies have found that TIMP gene family members are differentially expressed in multiple cancers [35–37]. Because MMPs are highly correlated with the prognosis of multiple cancers, TIMPs, at least theoretically, may affect prognosis in some cancer cases as specific inhibitors. In brain tumours, including glioma, many reports have investigated the differential expression of TIMPs [38–40]. However, previous reports on TIMPs in GBM are largely fragmented, and systematic analysis of the TIMP family in GBM is rare. In the present study, we performed systemic analysis concerning TIMPs for the prognosis of patients with GBM.

As shown in the results (Fig. 1), TIMPs were differentially expressed in brain and CNS cancer, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer, a finding that is also consistent with previous reports [35, 41]. Interestingly, the expression levels of these genes were almost all upregulated in brain and CNS cancer, but TIMP expression was downregulated in normal individuals (Fig. 2). TIMP-1 demonstrated both antitumour and antimetastatic functions in multiple genetic models [42, 43]. However, in our study, TIMP1 expression was not associated with the prognosis of GBM (Fig. 3A). Most of the studies on TIMP1 gene expression levels showed a negative relationship with prognosis [44, 45]. High TIMP-1 expression is strongly associated with a poor prognosis in almost all known cancer types [46]. Many explanations exist for this contradictory phenomenon, such as the interaction between TIMP1 and CD63 to activate MAPK signalling and participation in the HGF/c-Met pathway to promote cancer progression. Additionally, MMPs have demonstrated potential cancer-inhibiting effects [47, 48]. Our results were not significant, a finding similar to the findings of Paulina Vaitkiene [49]. However, the high expression group of TIMP1 showed a poor prognosis, similar to the findings of Charlotte Aaberg-Jessen [40]. This phenomenon may be due to the insufficient number of patients and requires further work.

TIMP-2 is a unique member of the TIMP family because it directly inhibits endothelial cell proliferation instead of metalloproteinase activity [50]. TIMP2 has recently made adequate progress among biomarkers of renal injury [51, 52]. Regarding cancer, the current findings show that the role of TIMP2 in prognosis depends on the tissue of origin of the tumor [53]. However, epigenetic silencing of TIMP2 can promote invasion of ovarian cancer (OC) [54]. Concerning renal cell carcinoma (RCC), TIMP2 is inversely correlated with markers of tumour progression [55]. However, TIMP2 is a poor prognostic marker in gastric cancer [56], in contrast to its role in colorectal cancer [57]. TIMP2 is involved in glioma inhibition by different drugs as an intermediate link in the upregulated expression in different studies [58, 59]. However, regarding GBM, laboratory evidence has shown that TIMP2 promotes MMP2 activation and GBM cell invasion [60]. This finding indicates that the effect of TIMP2 on GBM is more complex than previously thought in the real environment. We showed that TIMP2 expression was positive, although not significantly, associated with the prognosis of GBM patients (Fig. 3A). This result may also be a manifestation of its complex role.

TIMP3 is the only TIMP family gene with an affinity for proteoglycans in the ECM, and it has the broadest range of substrates [61]. TIMP3 frequently leads to a poor prognosis because of silencing in tumours [46]. In addition to being a marker for predicting cancer progression, TIMP3 can also be used as a therapeutic target for cancer and a marker of tumour sensitivity to drugs [62–64]. In conclusion, TIMP3 has been shown to play a role in inhibiting cancer progression in numerous studies. A similar role has been reported for TIMP3 in glioma. MicroRNA 21 (miR-21) enhances the malignant degree of glioma by inhibiting TIMP3 expression [65]. In another study, upregulated expression of TIMP3 emerged in euxanthone-inhibited GBM cell lines [66]. TIMP3 can suppress angiogenesis by binding to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and disrupting the interaction of VEGF with VEGFR2 and downstream signalling [67]. Additionally, TIMP3 induces apoptosis and inhibits cell proliferation [68]. These functions all underlie TIMP3 as an inhibitor in various cancers, including GBM. Our findings also reflect these characteristics of TIMP3. TIMP3 overexpression was associated with better prognosis in GBM patients for both OS and DSS (Fig. 3A). This finding provides evidence for the positive impact of TIMP3 on the prognosis of GBM patients and validates the potential of TIMP3 as an intermediate link in drug therapy for various malignancies, including GBM, for further development. We also list genes associated with differential expression of TIMP3 in GBM that may develop similar application values to TIMP3 because of its similar role in GBM (Fig. 3D). Existing studies also demonstrated similar potential for these genes. For example, TOP2 is a member of the TOB/BTG protein family and inhibits cell proliferation and stimulates cell differentiation [69]. The dysregulation of TOP2 is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [70]. MTMR3 belongs to the myotubularin-related protein family and is a target gene of various miRNAs that regulate tumour development [71, 72]. MTMR3 modulates the proliferative phenotype and apoptosis of glioma cells by mediating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and correlates with glioma grade [73]. EIF4ENIF1 encodes a nucleocytoplasmic shuttle protein for the translation initiation factor eIF4E that constitutes a repressor complex involved in neurogenesis and confers resistance to DNA damaging agents through interaction with eIF4 [74–76].

TIMP4 is expressed only in specific tissues of the human body, and this restricted expression implies its functional specificity compared with other family members [77]. Thus, relatively few studies have investigated the role of TIMP4 in tumours, making its role in some tumours unclear in published studies. In studies on renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), TIMP4 showed opposite expression patterns in clear cell and papillary cell carcinomas [78]. regarding breast cancer, in contrast to Wang’s study in which TIMP4 played a role in stimulating tumorigenesis [79], Jiang’s study showed that TIMP4 inhibited tumour growth and invasion [80]. Recent studies have revealed that TIMP4 is involved in the inhibitory effect of various substances on cancer, showing a negative regulatory role in the progression of various tumours. Low TIMP4 expression induces resistance to chemotherapeutic agents in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [81]. Stable TIMP-4 knockdown promotes the proliferation and migration of well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDLS) [82]. In bladder and prostate tumours, TIMP4 is downregulated by chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1) as an intermediate link to maintain tumour growth [83]. Regarding the relationship between TIMP4 and glioma progression, the directivity of the available findings is inconsistent. TIMP4 binds CRN2 (an actin filament binding protein) and promotes perivascular invasion of GBM cells [84]. High TIMP4/CD63 coexpression contributes to the poor prognosis of GBM patients [85]. TIMP4 has been shown in Pullen’s study to have an inverse expression relationship with MMP1, which performs enhanced tumorigenic function in GBM [86]. TIMP4 is also downregulated during human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) promotion of glioma development and progression [87]. In our study, high TIMP4 expression was associated with better OS in GBM patients. Although the relationship between the expression level of TIMP4 and DSS was not significant, the effect of TIMP4 expression on DSS was positive (Fig. 3A). This result may be explained by the insufficient number of enrolled patients. Notably, a significantly positive relationship was found between TIMP4 and TIMP3 expression (Fig. 3B), warranting further investigation and providing evidence for the effect of TIMP4 on the prognosis of GBM patients. Finally, a list of genes highly correlated with TIMP4 expression is also provided for exploration (Fig. 3D). Recent studies provide a basis for the further exploration of these genes. For example, SCRG1 (Scrapie Responsive Gene 1) is involved in neurodegeneration and autophagy and is associated with transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. It can also maintain the stemness of stem cells through the SCRG1/BST1 axis [88–90]. SHISA4 belongs to the SHISA family and mediates synaptic transmission in the central nervous system by constituting an auxiliary subunit of the AMPA receptor [91]. COMMD2 is the second member of the copper metabolism MURR1 domain protein family, in which COMMD1 inhibits GBM cell proliferation and promotes lung cancer cell apoptosis [92, 93].

Based on the clinical and molecular pathological features of GBM, multiple classification methods exist. Our study demonstrated that the expression of TIMP family genes did not show a correlation with sex. The gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) distinguishes GBM patients from IDH-mutant (IDH-mt) and wild-type (IDH-wt) GBM patients [94]. Existing studies have shown that the IDH mutant body type has a better prognosis and therapeutic effect than the IDH wild-type, accounting for approximately 10% of GBM [95, 96]. TIMP1 expression was markedly elevated in wild-type GBM, corresponding to patients with high TIMP1 expression showing a worse prognosis, although not significantly. TIMP2 expression did not differ greatly between the two groups, corresponding to the close results of the two prognostic subgroups. The MGMT gene is associated with DNA repair, and its methylation produces gene silencing, allowing glioblastoma patients receiving chemotherapy to achieve a better prognosis [97]. We observed even lower TIMP1 expression in MGMT-methylated patients, a finding that may also be responsible for the better prognosis of patients with downregulated TIMP1 expression. GBM was originally divided into four subtypes according to gene expression profiles—classical, mesenchymal, proneural, and neural [98]. However, some studies have found that the neural subtype is produced because normal samples are contaminated [99]. Mutations of EGFR often occur in the classical subtype, and it and the mesenchymal subtype are more likely to be affected by aggressive treatment [96]. GBM patients with proneural subtypes frequently have rare genetic mutations, particularly IDH mutations with better prognosis [99]. Our study lays the foundation to evaluate the mechanism and how differential expression of TIMPs affects the survival of GBM patients with central subtypes.

The tumour microenvironment (TME) has gained increasing attention because it regulates tumour progression and significantly affects the treatment response [100, 101]. The infiltration of immune cells in the TME promotes or antagonizes tumours [102]. We analysed the effect of TIMP family members on immune cell infiltration in GBM with the TIMER database and found that the expression and CNV of TIMPs are closely related to the infiltration of six immune cells. These four members can be identified in GBM because of differences in multiple microenvironment indicators, including tumour purity. Our results help to further reveal the molecular mechanism of GBM progression and are expected to use this gene family as a link in immunotherapy to specifically affect the GBM tumour microenvironment and improve the treatment of GBM.

Our study has some limitations, primarily because our data were all obtained from public databases, making some heterogeneity in the source and use of the data inevitable. Our results mainly provide a direction and basis for studies targeting TIMPs in GBM. Further experimental and clinical validation for translational purposes is warranted.

Conclusion

We conducted a systematic study on the expression, prognosis, and immune infiltration of TIMPs in GBM. Our results confirm that the expression of all four members of the TIMP family is upregulated in GBM. High expression of both TIMP3 and TIMP4 can be used as a predictor of better survival in GBM patients and a positive relationship was found between them. These findings led to the identification of related genes for further analysis. Finally, the expression of this gene family was associated with the infiltration of immune cells, including CD4+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, B cells, CD8+ T cells, and dendritic cells, to varying degrees. This effect provides new exploration directions for research on the TIMP family and GBM.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- TIMPs

The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- OS

Overall survival

- DSS

Disease special survival

- EPA

Erythroid-potentiating activity

- NSCs

Neural stem cells

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- GEPIA

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- CGGA

Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IDH

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- PPI

Protein-protein interactions

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- CNV

Copy number variation

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- miR-21

MicroRNA 21

- VEGFR2

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

- RCC

Renal cell carcinomas

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- WDLS

Well-differentiated liposarcoma

- HHV-6

Human herpesvirus 6

Authors’ contributions

JH designed the study plan and was the main writer of the manuscript. YJ participated in the design of the study and was the main modifier of the manuscript. FH carried out the data analysis and the production of figures. PS provided financial support and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 8167050561). The institutions that provided funding did not participate in the data analysis, article writing, and submission decision of this paper.

Availability of data and materials

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Institutional review board approval was not demanded in our study for all database is publicly available; This data can be found in following website. Oncomine: http://www.oncomine.org; GEPIA2: http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/; OSgbm: http://bioinfo.henu.edu.cn/GBM/GBMList.jsp; LinkedOmics: http://www.linkedomics.orglogin.php; STRING: https://string-db.org; GeneMANIA: http://www.genemania.org; Enrichr: https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/; KEGG: https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html; cBioPortal: http://cbioportal.org; TIMER: https://cistrome.org/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG, Deltour I, Fisher JL, Langer CE, et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(7):896–913. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu P, Takai K, Weaver VM, Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ahir BK, Engelhard HH, Lakka SS. Tumor development and angiogenesis in adult brain tumor: glioblastoma. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57(5):2461–2478. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01892-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JR, Li XH, Gao XJ, An SC, Liu H, Liang J, et al. Expression of MMP-13 is associated with invasion and metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(4):427–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai X, Zhu H, Li Y. PKCζ, MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in lung adenocarcinoma and association with a metastatic phenotype. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(6):8301–8306. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenig S, Alonso MB, Mueller MM, Lah TT. Glioblastoma and endothelial cells cross-talk, mediated by SDF-1, enhances tumour invasion and endothelial proliferation by increasing expression of cathepsins B, S, and MMP-9. Cancer Lett. 2010;289(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Gelatinases (MMP-2 and -9) and their natural inhibitors as prognostic indicators in solid cancers. Biochimie. 2005;87(3-4):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arpino V, Brock M, Gill SE. The role of TIMPs in regulation of extracellular matrix proteolysis. Matrix Biol. 2015;44-46:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ries C. Cytokine functions of TIMP-1. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(4):659–672. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1457-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert E, Dassé E, Haye B, Petitfrère E. TIMPs as multifacial proteins. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49(3):187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita K, Suzuki M, Iwata H, Koike T, Hamaguchi M, Shinagawa A, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation is crucial for growth signaling by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) FEBS Lett. 1996;396(1):103–107. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singla DK, McDonald DE. Factors released from embryonic stem cells inhibit apoptosis of H9c2 cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(3):H1590–H1595. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00431.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MF, Ricke WA, Bakke LJ, Dow MP, Smith GW. Ovarian tissue remodeling: role of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;191(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz-Munoz W, Khokha R. The role of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2008;45(3):291–338. doi: 10.1080/10408360801973244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fassina G, Ferrari N, Brigati C, Benelli R, Santi L, Noonan DM, et al. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases: regulation and biological activities. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18(2):111–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1006797522521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–Ww60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong H, Wang Q, Li N, Lv J, Ge L, Yang M, et al. OSgbm: an online consensus survival analysis web server for glioblastoma. Front Genet. 2019;10:1378. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasaikar SV, Straub P, Wang J, Zhang B. LinkedOmics: analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D956–Dd63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman RL, Wang Q, Carro A, Verhaak RG, Squatrito M. GlioVis data portal for visualization and analysis of brain tumor expression datasets. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(1):139–141. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W214–W220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie Z, Bailey A, Kuleshov MV, Clarke DJB, Evangelista JE, Jenkins SL, et al. Gene set knowledge discovery with enrichr. Curr Protoc. 2021;1(3):e90. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e108–ee10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bredel M, Bredel C, Juric D, Harsh GR, Vogel H, Recht LD, et al. Functional network analysis reveals extended gliomagenesis pathway maps and three novel MYC-interacting genes in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8679–8689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, Li A, Su Q, Donin NM, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(5):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang Y, Diehn M, Watson N, Bollen AW, Aldape KD, Nicholas MK, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals molecularly and clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma multiforme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(16):5814–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shai R, Shi T, Kremen TJ, Horvath S, Liau LM, Cloughesy TF, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies molecular subtypes of gliomas. Oncogene. 2003;22(31):4918–4923. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murat A, Migliavacca E, Gorlia T, Lambiv WL, Shay T, Hamou MF, et al. Stem cell-related “self-renewal” signature and high epidermal growth factor receptor expression associated with resistance to concomitant chemoradiotherapy in glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3015–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun L, Hui AM, Su Q, Vortmeyer A, Kotliarov Y, Pastorino S, et al. Neuronal and glioma-derived stem cell factor induces angiogenesis within the brain. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(4):287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Böckelman C, Beilmann-Lehtonen I, Kaprio T, Koskensalo S, Tervahartiala T, Mustonen H, et al. Serum MMP-8 and TIMP-1 predict prognosis in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):679. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4589-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozden F, Saygin C, Uzunaslan D, Onal B, Durak H, Aki H. Expression of MMP-1, MMP-9 and TIMP-2 in prostate carcinoma and their influence on prognosis and survival. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(8):1373–1382. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1453-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azevedo Martins JM, Rabelo-Santos SH, do Amaral Westin MC, Zeferino LC. Tumoral and stromal expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and VEGF-A in cervical cancer patient survival: a competing risk analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):660. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo H, Sun Z, Wei J, Xiang Y, Qiu L, Guo L, et al. Expressions of matrix metalloproteinases-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in pituitary adenomas and their relationships with prognosis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2019;34(1):1–6. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2018.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mashayekhi F, Saberi A, Mashayekhi S. Serum TIMP1 and TIMP2 concentration in patients with different grades of meningioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;170:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aaberg-Jessen C, Christensen K, Offenberg H, Bartels A, Dreehsen T, Hansen S, et al. Low expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) in glioblastoma predicts longer patient survival. J Neurooncol. 2009;95(1):117–128. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9910-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu ZS, Wu Q, Yang JH, Wang HQ, Ding XD, Yang F, et al. Prognostic significance of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 serum and tissue expression in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(9):2050–2056. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khokha R. Suppression of the tumorigenic and metastatic abilities of murine B16-F10 melanoma cells in vivo by the overexpression of the tissue inhibitor of the metalloproteinases-1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(4):299–304. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khokha R, Waterhouse P, Yagel S, Lala PK, Overall CM, Norton G, et al. Antisense RNA-induced reduction in murine TIMP levels confers oncogenicity on Swiss 3T3 cells. Science. 1989;243(4893):947–950. doi: 10.1126/science.2465572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Würtz S, Schrohl AS, Sørensen NM, Lademann U, Christensen IJ, Mouridsen H, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(2):215–227. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grunnet M, Mau-Sørensen M, Brünner N. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) as a biomarker in gastric cancer: a review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(8):899–905. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.812235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson HW, Defamie V, Waterhouse P, Khokha R. TIMPs: versatile extracellular regulators in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(1):38–53. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grünwald B, Vandooren J, Gerg M, Ahomaa K, Hunger A, Berchtold S, et al. Systemic ablation of MMP-9 triggers invasive growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer via deregulation of IL6 expression in the bone marrow. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14(11):1147–1158. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jobin PG, Butler GS, Overall CM. New intracellular activities of matrix metalloproteinases shine in the moonlight. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864(11 Pt A):2043–2055. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaitkiene P, Urbanaviciute R, Grigas P, Steponaitis G, Tamasauskas A, Skiriutė D. Identification of astrocytoma blood serum protein profile. Cells. 2019;9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Seo DW, Li H, Guedez L, Wingfield PT, Diaz T, Salloum R, et al. TIMP-2 mediated inhibition of angiogenesis: an MMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 2003;114(2):171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00551-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andreucci M, Faga T, Pisani A, Perticone M, Michael A. The ischemic/nephrotoxic acute kidney injury and the use of renal biomarkers in clinical practice. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;39:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waskowski J, Pfortmueller CA, Schenk N, Buehlmann R, Schmidli J, Erdoes G, et al. (TIMP2) x (IGFBP7) as early renal biomarker for the prediction of acute kidney injury in aortic surgery (TIGER). A single center observational study. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0244658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eckfeld C, Häußler D, Schoeps B, Hermann CD, Krüger A. Functional disparities within the TIMP family in cancer: hints from molecular divergence. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019;38(3):469–481. doi: 10.1007/s10555-019-09812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi X, Guo J, Guo J, Sun S, Yang P, Wang J, et al. EZH2-mediated epigenetic silencing of TIMP2 promotes ovarian cancer migration and invasion. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3568. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03362-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lyu J, Zhu Y, Zhang Q. An increased level of MiR-222-3p is associated with TMP2 suppression, ERK activation and is associated with metastasis and a poor prognosis in renal clear cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2020;28(2):141–149. doi: 10.3233/CBM-190264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang W, Zhang Y, Liu M, Wang Y, Yang T, Li D, et al. TIMP2 is a poor prognostic factor and predicts metastatic biological behavior in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9629. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27897-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin Z, Zhang G, Liu Y, He Y, Yang C, Du Y, et al. The suppressive role of HYAL1 and HYAL2 in the metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34(10):1766–1776. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Z, Wang B, Shi Y, Xu C, Xiao HL, Ma LN, et al. Oncogenic miR-20a and miR-106a enhance the invasiveness of human glioma stem cells by directly targeting TIMP-2. Oncogene. 2015;34(11):1407–1419. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mei PJ, Chen YS, Du Y, Bai J, Zheng JN. PinX1 inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion in glioma cells. Med Oncol. 2015;32(3):73. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0545-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu KV, Jong KA, Rajasekaran AK, Cloughesy TF, Mischel PS. Upregulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2 promotes matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 activation and cell invasion in a human glioblastoma cell line. Lab Invest. 2004;84(1):8–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.labinvest.3700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan D, Kassiri Z. Biology of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and its therapeutic implications in cardiovascular pathology. Front Physiol. 2020;11:661. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Span PN, Lindberg RL, Manders P, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Heuvel JJ, Beex LV, et al. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase expression in human breast cancer: TIMP-3 is associated with adjuvant endocrine therapy success. J Pathol. 2004;202(4):395–402. doi: 10.1002/path.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deng X, Bhagat S, Dong Z, Mullins C, Chinni SR, Cher M. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells and confers increased sensitivity to paclitaxel. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(18):3267–3273. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu JL, Lv P, Han J, Zhu X, Hong LL, Zhu WY, et al. Methylated TIMP-3 DNA in body fluids is an independent prognostic factor for gastric cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(11):1466–1473. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0285-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gabriely G, Wurdinger T, Kesari S, Esau CC, Burchard J, Linsley PS, et al. MicroRNA 21 promotes glioma invasion by targeting matrix metalloproteinase regulators. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(17):5369–5380. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00479-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li W, Du H, Zhou G, Song D. Euxanthone represses the proliferation, migration, and invasion of glioblastoma cells by modulating STAT3/SHP-1 signaling. Anat Rec. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Qi JH, Ebrahem Q, Moore N, Murphy G, Claesson-Welsh L, Bond M, et al. A novel function for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP3): inhibition of angiogenesis by blockage of VEGF binding to VEGF receptor-2. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):407–415. doi: 10.1038/nm846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker AH, George SJ, Zaltsman AB, Murphy G, Newby AC. Inhibition of invasion and induction of apoptotic cell death of cancer cell lines by overexpression of TIMP-3. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(9-10):1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winkler GS. The mammalian anti-proliferative BTG/Tob protein family. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222(1):66–72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen H, Li W, Tian Y, Xu P, Wang H, Zhang J, et al. Upregulation of miR-362-3p modulates proliferation and anchorage-independent growth by directly targeting Tob2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(8):1563–1573. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin Y, Zhao J, Wang H, Cao J, Nie Y. miR-181a modulates proliferation, migration and autophagy in AGS gastric cancer cells and downregulates MTMR3. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15(5):2451–2456. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gong Y, He T, Yang L, Yang G, Chen Y, Zhang X. The role of miR-100 in regulating apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11650. doi: 10.1038/srep11650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yan Y, Yan H, Wang Q, Zhang L, Liu Y, Yu H. MicroRNA 10a induces glioma tumorigenesis by targeting myotubularin-related protein 3 and regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. FEBS J. 2019;286(13):2577–2592. doi: 10.1111/febs.14824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martínez A, Sesé M, Losa JH, Robichaud N, Sonenberg N, Aasen T, et al. Phosphorylation of eIF4E confers resistance to cellular stress and DNA-damaging agents through an interaction with 4E-T: a rationale for novel therapeutic approaches. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dostie J, Ferraiuolo M, Pause A, Adam SA, Sonenberg N. A novel shuttling protein, 4E-T, mediates the nuclear import of the mRNA 5’ cap-binding protein, eIF4E. EMBO J. 2000;19(12):3142–3156. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Räsch F, Weber R, Izaurralde E, Igreja C. 4E-T-bound mRNAs are stored in a silenced and deadenylated form. Genes Dev. 2020;34(11-12):847–860. doi: 10.1101/gad.336073.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Melendez-Zajgla J, Del Pozo L, Ceballos G, Maldonado V. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-4. The road less traveled. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hagemann T, Gunawan B, Schulz M, Füzesi L, Binder C. mRNA expression of matrix metalloproteases and their inhibitors differs in subtypes of renal cell carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(15):1839–1846. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang M, Liu YE, Greene J, Sheng S, Fuchs A, Rosen EM, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis of human breast cancer cells transfected with tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4. Oncogene. 1997;14(23):2767–2774. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang Y, Wang M, Celiker MY, Liu YE, Sang QX, Goldberg ID, et al. Stimulation of mammary tumorigenesis by systemic tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 4 gene delivery. Cancer Res. 2001;61(6):2365–2370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang YW, Zheng Y, Wang JZ, Lu XX, Wang Z, Chen LB, et al. Integrated analysis of DNA methylation and mRNA expression profiling reveals candidate genes associated with cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Epigenetics. 2014;9(6):896–909. doi: 10.4161/epi.28601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shrestha M, Ando T, Chea C, Sakamoto S, Nishisaka T, Ogawa I, et al. The transition of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases from -4 to -1 induces aggressive behavior and poor patient survival in dedifferentiated liposarcoma via YAP/TAZ activation. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40(10):1288–1297. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miyake M, Furuya H, Onishi S, Hokutan K, Anai S, Chan O, et al. Monoclonal antibody against CXCL1 (HL2401) as a novel agent in suppressing IL6 expression and tumoral growth. Theranostics. 2019;9(3):853–867. doi: 10.7150/thno.29553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Solga R, Behrens J, Ziemann A, Riou A, Berwanger C, Becker L, et al. CRN2 binds to TIMP4 and MMP14 and promotes perivascular invasion of glioblastoma cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2019;98(5-8):151046. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2019.151046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rorive S, Lopez XM, Maris C, Trepant AL, Sauvage S, Sadeghi N, et al. TIMP-4 and CD63: new prognostic biomarkers in human astrocytomas. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(10):1418–1428. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pullen NA, Anand M, Cooper PS, Fillmore HL. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression enhances tumorigenicity as well as tumor-related angiogenesis and is inversely associated with TIMP-4 expression in a model of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2012;106(3):461–471. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gu B, Li M, Zhang Y, Li L, Yao K, Wang S. DR7 encoded by human herpesvirus 6 promotes glioma development and progression. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:2109–2118. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S179762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chosa N, Ishisaki A. Two novel mechanisms for maintenance of stemness in mesenchymal stem cells: SCRG1/BST1 axis and cell-cell adhesion through N-cadherin. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dron M, Bailly Y, Beringue V, Haeberlé AM, Griffond B, Risold PY, et al. Scrg1 is induced in TSE and brain injuries, and associated with autophagy. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(1):133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dron M, Bailly Y, Beringue V, Haeberlé AM, Griffond B, Risold PY, et al. SCRG1, a potential marker of autophagy in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Autophagy. 2006;2(1):58–60. doi: 10.4161/auto.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abdollahi Nejat M, Klaassen RV, Spijker S, Smit AB. Auxiliary subunits of the AMPA receptor: The Shisa family of proteins. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2021;58:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mu P, Akashi T, Lu F, Kishida S, Kadomatsu K. A novel nuclear complex of DRR1, F-actin and COMMD1 involved in NF-κB degradation and cell growth suppression in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2017;36(41):5745–5756. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fernández Massó JR, Oliva Argüelles B, Tejeda Y, Astrada S, Garay H, Reyes O, et al. The antitumor peptide CIGB-552 increases COMMD1 and inhibits growth of human lung cancer cells. J Amino Acids. 2013;2013:251398. doi: 10.1155/2013/251398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tan AC, Ashley DM, López GY, Malinzak M, Friedman HS, Khasraw M. Management of glioblastoma: state of the art and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):299–312. doi: 10.3322/caac.21613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ceccarelli M, Barthel FP, Malta TM, Sabedot TS, Salama SR, Murray BA, et al. Molecular profiling reveals biologically discrete subsets and pathways of progression in diffuse glioma. Cell. 2016;164(3):550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kristensen BW, Priesterbach-Ackley LP, Petersen JK, Wesseling P. Molecular pathology of tumors of the central nervous system. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1265–1278. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hinshaw DC, Shevde LA. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79(18):4557–4566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wu T, Dai Y. Tumor microenvironment and therapeutic response. Cancer Lett. 2017;387:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lei X, Lei Y, Li JK, Du WX, Li RG, Yang J, et al. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Institutional review board approval was not demanded in our study for all database is publicly available; This data can be found in following website. Oncomine: http://www.oncomine.org; GEPIA2: http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/; OSgbm: http://bioinfo.henu.edu.cn/GBM/GBMList.jsp; LinkedOmics: http://www.linkedomics.orglogin.php; STRING: https://string-db.org; GeneMANIA: http://www.genemania.org; Enrichr: https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/; KEGG: https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html; cBioPortal: http://cbioportal.org; TIMER: https://cistrome.org/.