Abstract

Background:

There is no international consensus definition of ‘wellbeing’. This has led to wellbeing being captured in many different ways.

Aims:

To construct an inclusive, global operational definition of wellbeing.

Methods:

The differences between wellbeing components and determinants and the terms used interchangeably with wellbeing, such as health, are considered from the perspective of a doctor. The philosophies underpinning wellbeing and modern wellbeing research theories are discussed in terms of their appropriateness in an inclusive definition.

Results:

An operational definition is proposed that is not limited to doctors, but universal, and inclusive: ‘Wellbeing is a state of positive feelings and meeting full potential in the world. It can be measured subjectively and objectively, using a salutogenic approach’.

Conclusions:

This operational definition allows the differentiation of wellbeing from terms such as quality of life and emphasises that in the face of global challenges people should still consider wellbeing as more than the absence of pathology.

Keywords: Wellbeing, definition, doctors

Introduction

‘Wellbeing’ became a favoured concept at global, national and local governmental levels in the decade before the Covid-19 pandemic, emerging as a national outcome to rival Gross Domestic Product (Hogan et al., 2015), the effect of wellbeing on productivity being of particular concern. Now masked, visored, gowned and gloved, it is difficult to see the wellbeing of doctors in a pandemic and to predict how much longer they can be productive. Even before Covid-19, doctors’ wellbeing was described internationally in terms of burnout, with 32% to 80% of doctors surveyed at high risk of being ‘burnt out’ (British Medical Association, 2019; Huang, 2019; Margiotta, 2019; Robinson et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019; Tawfik et al, 2018; Yates & Samuel, 2019). Yet ‘Burnout’ is a pathological state described in the International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2018)whereas ‘Wellbeing’ is a positive noun: measuring wellbeing like a pathology limits ambitions to surviving and not becoming unwell, with no ability to measure thriving.

The reason researchers turn to burnout measurement tools to capture wellbeing is because burnout is clearly operationalised, whereas wellbeing remains a nebulous term. There is no international consensus definition, although authors agree one is needed (Felce & Perry, 1995; Gable & Haidt, 2005). In the absence of an agreed definition, many synonyms, descriptions, lists of wellbeing components or determinants, are used interchangeably when wellbeing is discussed, making it hard to compare wellbeing research studies.

The Cambridge Dictionary simplifies the definition of the noun ‘wellbeing’ to:

‘. . .the state of feeling healthy and happy’ (Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Although this is short and clear it highlights some of the problems in operationalising wellbeing. The inclusion of the adjective ‘healthy’ demonstrates the underlying assumption that health is a key component of wellbeing. This overlap with health is perpetuated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of health, which includes the noun wellbeing:

‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. (WHO, 1948)

Health and wellbeing are on the surface described as the same thing. However, a person who is not healthy is not automatically excluded from a state of wellbeing using the Cambridge definition (Cambridge University Press, 2019); their state is judged by how they feel about their health. This illustrates another underlying assumption: that wellbeing can only be subjectively assessed. It would follow that wellbeing cannot be objectively evaluated by independent third parties, such as occupational health services.

Subjective evaluation of wellbeing requires the individual to determine their own standards against which to compare their life and relies partly on liberal individualism (Christopher, 1999). However, in China, collectivism is more prevalent, and it is common for a person to be modest and report poor wellbeing, even when it is felt to be good, so that family and friends can offer their positive opinion of the person’s wellbeing (Christopher, 1999). A definition of wellbeing needs to be inclusive of different cultures, or international comparisons cannot be made, and therefore objective measurement should be considered.

Ontology is the philosophical study of being, but in computer and information science it is the description of all the parts that exists within and the relationship and hierarchy between those parts: the naming, grouping and categorising of parts. In this narrative review from the perspective of a doctor, both approaches will be used to explore what wellbeing is and to create an operational definition.

Terms used to describe wellbeing

The term Wellbeing is not neutral, but has inherent positive attributions. Unlike ‘happiness’, it does not have its own adjectives like ‘happy’ and ‘unhappy’ that describe a presence or absence of the state and can be prefaced with an adverb like ‘very’ to imply a spectrum of happiness. It might not be appropriate to have terms that describe a presence, or absence, of wellbeing, as wellbeing may always be present, but to a greater or lesser extent. It has been theorised that there is a wellbeing ‘baseline’ around which individuals fluctuate, with incrementally positive numbers being achieved with increasing wellbeing, but with wellbeing never crossing zero (Cummins, 2010). Conceptualising the measurement of wellbeing in this unidimensional way is beneficial as it allows quantitative measures that fit Rasch Measurement Theory, by producing interval level data, where the difference between two values is meaningful (Langley & McKenna, 2021). Without a definition that uses ontology to identify the parts of wellbeing, even these basic concepts cannot be agreed.

The relationship between wellbeing and nouns treated as synonyms: health, wellness, welfare and quality of life

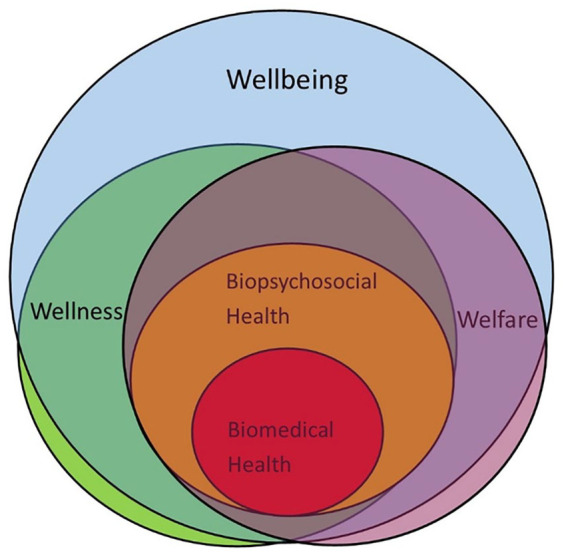

To ensure the operational definition of wellbeing is ‘fit for purpose’ the relationship of wellbeing to other similar nouns needs to be established. ‘Health and wellbeing’ are often grouped together in advertising products, interventions, job role titles and in describing populations. It is perhaps the traditional, biomedical, pathogenic approach to health that separates it from wellbeing, which is broader and needs to be approached in a holistic and salutogenic way, with the focus on the positive aspects of human experience (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Concept diagram of the proposed relationship between health, wellness, welfare and wellbeing.

The seeming need for the WHO to prefix the word ‘wellbeing’ with ‘physical, mental and social’ in its definition of health (WHO, 1948) is emblematic of the lack of a wellbeing definition. Applying the biopsychosocial health model to wellbeing with these prefixes is unhelpful as it creates further overlap between the terms: health and wellbeing. If wellbeing represents a new holistic approach to health it should be freed from the unhelpful false dichotomy of physical and mental: no part of the human experience, and no determinant, is purely physical or mental. Health and wellbeing are both latent concepts, which we have traditionally recognised through their absence. Using a salutogenic approach to measuring wellbeing helps separate wellbeing from health (Table 1).

Table 1.

The different characteristics of the terms used interchangeably with wellbeing.

| Characteristics | Wellbeing | Health | Welfare | Wellness | QOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who measures it? | Individual or third party | Individual or third party | Third party | Individual | Individual |

| Where is it used? | Public and private sector | Healthcare | Social policy | Mental health | Health economics |

| Approach | Salutogenic | Pathogenic | Passive | Active | Comparative |

Note. QOL = quality of life.

‘Wellness’ is a term being used by the UK charity ‘Mind’ for action plans (Mind, 2020) for maintaining mental health, and by Health Education England for inductions for UK National Health Service learners (Health Education England, 2020b). It further confuses wellbeing research. It has been defined as:

‘the active pursuit of activities, choices and lifestyles that lead to a state of holistic health’ (Global Wellness Institute, 2020)

Wellness differs from wellbeing in being an active noun, whereas wellbeing is passive. This could be interpreted as a difference in terms of responsibility: the responsibility for the state of wellbeing is more external to the individual although the measurement might be done by the individual, whereas wellness is usually measured by and the responsibility of the individual (Bart et al., 2018). Wellness is therefore not a useful concept for examining system level problems.

The noun ‘welfare’ would appear to overlap greatly with wellbeing, as most definitions include the components ‘health’ and ‘happiness’ (Cambridge University Press, 2019). Welfare is additionally associated with prosperity, or the financial help given to those who need it, particularly in countries where there is a welfare system. The pecuniary component of welfare is what separates it from wellbeing, for which financial status is a determinant and not a component.

The concepts of quality of life and wellbeing have been developed separately and tend to be used without reference to each other. Wellbeing has been the outcome of choice in psychology and sociology, and quality of life the outcome of choice in healthcare (Hunt, 1997). In the UK, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) utilises Quality of Life while the Office for National Statistics utilises Wellbeing. There is a WHO definition for Quality of Life:

‘An individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationship to salient features of their environment’. (WHO, 1995, 2020)

The fact that the WHO now states that the idealist value judgement needed in Quality of Life dictates that it has to be measured subjectively (WHO, 1995) is what separates it from wellbeing, which the WHO states can be measured both subjectively and objectively (Vik & Carlquist, 2017).

‘Phenomena such as mastery, relatedness or autonomy can be comprehended either as subjective experiences or as objectively existing features of a person’ (Vik & Carlquist, 2017).

The capabilities, or achieved functions, approach can therefore be used to objectively capture determinants of wellbeing. Supporters of this approach argue that this removes the value judgement that might lead to this determinant being misleadingly reported due to the low expectations of the individual, or society (Robeyns, 2005; Sen, 2005). This makes wellbeing a more inclusive concept than health, wellness, welfare or quality of life.

Determinants versus components of wellbeing

In 2010 the UK launched the National Wellbeing Programme and the Office for National Statistics held the ‘What matters to you?’ debate, which identified 10 determinants of wellbeing that mattered most to the 7,250 respondents. People were asked:

‘What things in life matter to you? What is wellbeing?’

The 10 areas identified are determinants and not components of wellbeing, as they lead to an increase or decrease in wellbeing, rather than being the parts that combine to create the state of wellbeing: and are stipulated as

‘the natural environment, personal well-being, our relationships, health, what we do, where we live, personal finance, the economy, education and skills, and governance’. (Office for National Statistics, 2011)

Only pre-defined answers were offered in the ‘debate’ where free text determinants could have been captured and categorised using the resources and challenges concepts model (Dodge et al., 2012). The debate was also biased as despite attempting to try and target all population groups, through holding events in pertinent organisations, the respondents were not representative of the diversity of the UK general population.

Expressing wellbeing in terms of its determinants is problematic as it fails to operationalise wellbeing itself. It removes the focus from the state of the individual to the state of their bank account in the case of ‘personal finance’. In medicine the pathogenesis of a condition, the negative determinants, or challenges, are traditionally examined, and there is certainly far more published in medicine and psychology on pathology than on health (Gable & Haidt, 2005). Far less is published utilising salutogenic theory, which aims to examine what positive determinants, or resources, lead to a good state of health, or wellbeing (Corey, 2002; Duckworth et al., 2004).

As a positively loaded noun ‘wellbeing’ lends itself to being investigated using salutogenic theory, where the focus is determinants, in individuals or groups who have positive states of wellbeing, and on interventions that improve wellbeing. Unfortunately, pathogenic measurement of wellbeing is common, and ‘anxiety’ is part of the UK Office for National Statistics Personal Wellbeing Dashboard (Office for National Statistics, 2015). This poses a challenge as anxiety is a negative state and anxiety disorders are conditions listed in the International Classification of Disease (WHO, 2018). Having a salutogenic operational definition for wellbeing would help prevent this confusion between wellbeing and ill health.

The relationships between the terms used to describe wellbeing are complex. Determinants can have a positive or negative association with wellbeing: furthermore, the causal relationships between determinants and wellbeing work in both directions. Determinants can impact on the state of wellbeing and the state of wellbeing affects the response to determinants. These have been described as the ‘bottom-up’ or ‘top-down’ approaches (Diener & Ryan, 2009; Headey et al., 1991), with the bottom being the determinants and the top being wellbeing.

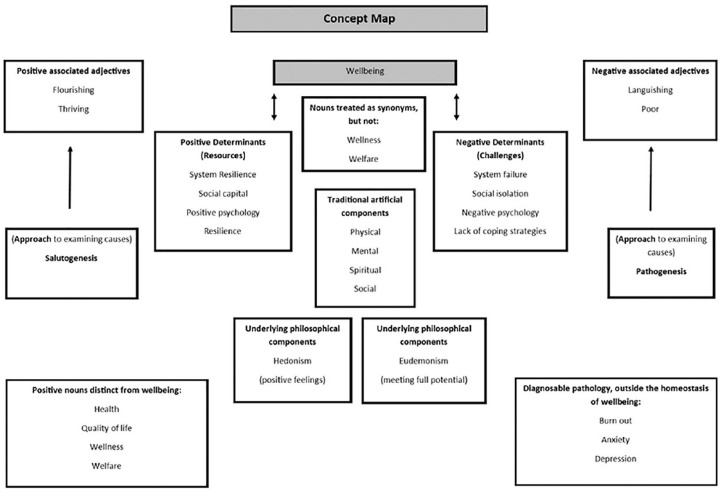

The ‘bottom up’ relationship may be cumulative, for example doctors who experience repeated negative determinants such as PPE shortages and high patient mortality rates would have disproportionally worse states of wellbeing (Diener, 1984; Diener & Ryan, 2009). The ‘bottom up’ approach to determinants of wellbeing leads to primary interventions for wellbeing, where the modifiable, system level, wellbeing problems are addressed, such as adequate staffing to allow rest. By contrast, the ‘top-down’ theory is used in personal resilience training, mindfulness and cognitive behavioural techniques, which aim to improve wellbeing by changing the way doctors attend to, interpret, and remember, determinants (Diener & Ryan, 2009). The ownership of the determinants lies more with the healthcare organisation with the ‘bottom up’ approach, and more with the individual doctor in the ‘top down’ approach. Clarifying the difference between wellbeing and its determinants in this way allows relationships to be properly researched. The relationship and hierarchy of wellbeing terms are explored in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Concept map of the relationship between terms applied to wellbeing.

Components of wellbeing

Happiness and Life Satisfaction are often used interchangeably with wellbeing. It has been demonstrated that these terms share a maximum of 50% to 60% common variance; the items that measure the synonyms do not correlate well (Cummins, 1998). The reason for this is that these terms are not interchangeable with wellbeing, they in fact reflect the two differing underlying philosophies.

Philosophy seeks to reveal the truth through logic and observation and should be impartial and unbiased. Two broad philosophies underpin modern wellbeing research: hedonism and eudonism. Understanding the philosophy behind the noun ‘wellbeing’ reveals the basic components required in an operational definition.

The Hedonist philosophy

The use of the adjective ‘happy’ in the Cambridge dictionary definition of wellbeing (Cambridge University Press, 2019) makes it a Hedonist definition. ‘Hedonism’ derives from the classical Greek word for pleasure and reflects the school of extreme hedonist philosophy led by Aristippus of Cyrene, in Greece in the third century BCE. Aristippus argued that the purpose of life was to pursue sensory pleasure at every opportunity, no matter the consequences (Tatarkiewicz, 1976). Today, doctors recognise health as a determinant of wellbeing, and health is negatively impacted by a lack of moderation in pleasure seeking, so this extreme hedonism cannot underpin a wellbeing definition.

The Epicurean school, formed in Greece around 100 years later provides the basis for the modern hedonist definitions of wellbeing. Epicurus valued spiritual pleasure above physical (Tatarkiewicz, 1976). The Epicurean school acknowledged that a state of wellbeing has a health component, but should be achievable in the face of other challenges, such as a lack of worldly goods. However, it should be noted that followers of the Epicurean school isolated themselves from society in their own self-sustaining community, with no costs of living to make a lack of worldly goods problematic (Mautner, 2000).

Hedonistic ideology

Ideologies tend to look for the unity in diversity; to identify a universal organising theory of wellbeing (Bradburn, 1969). Philosophy embraces disparate findings, thereby ensuring that the ‘truth’ about wellbeing is not missed. There is a danger, however, in continually exploring the diversity of wellbeing that an operational definition is never agreed (Bradburn, 1969).The modern approach to hedonism described by Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century takes into account the conflicts of interest that doctors in modern society encounter. He described the ideology of utilitarianism, which suggests actions are worth taking that will lead to the most happiness for most people: this ideology places our collective, rather than individual, wellbeing at the forefront of all concerns. The main criticism of utilitarianism is humans do not strive for happiness alone.

Eudemonic philosophy

‘Languishing’, ‘thriving’ or ‘flourishing’, are often used as adjectives to describe a person’s state of wellbeing. The implication of these adjectives is that a person must be experiencing a sense of personal growth (rather than stasis) to achieve a state of wellbeing and follows the philosophy of eudemonism. Plato is believed to have first used the term ‘eudemonia’. Debate exists around Plato’s exact meaning of the term and his pupil, Aristotle, is usually quoted for his interpretation of eudemonia: ‘meeting your full potential’ (Kashdan et al., 2008).

John Locke, the English philosopher, revisited eudemonism in the 17th century, writing that pleasure could be found in exercising virtue (Mautner, 2000). In Aristotle’s and Locke’s interpretations of eudemonism, meeting your full potential, or being virtuous, was not devoid of good feelings. The good feelings were a by-product of the wellbeing activities, as opposed to the reason to undertake the activity. Doing virtuous things to create good feelings may indeed be the reason some doctors choose their profession. In deciding if an individual has met their full potential a value judgement about whether it is the full potential for the individual, or for the society they live in, is needed. Meeting full potential as an individual may require an individual to be selfish, which is at odds with the concept of virtue, suggesting that Aristotle and Locke intended the full potential to be in relation to society and this is what should be clear in a definition of wellbeing.

Inclusive wording of components of wellbeing

Meeting full potential in relation to society is more culturally inclusive. Internationally, having children may decrease parental happiness, but increase meaning in life and wellbeing (Nussbaum, 2000). In China, a person may be more likely to look at how dutiful they are to their family to assess their wellbeing rather than their own feelings (Christopher, 1999). In the West we focus on and measure self-centred emotion. In more collectivist cultures, such as in traditional Japan, other-centred emotions are given nouns that do not exist in English, such as ‘amae’, which connotes ‘hopeful anticipation of another’s indulgence’ (Christopher, 1999). This highlights the care that is needed when choosing the components by which wellbeing is defined to make a definition inclusive. For this reason positive feelings, rather than happiness may be a more inclusive term to represent hedonism, without using the inaccessible and often pathologising term ‘affect’. Likewise, the term ‘meeting full potential’ is preferable to ‘fulfilment’ to represent eudemonism. ‘Fulfilment’ works only at the individual, rather than the societal level, having individualist underpinnings, and does not allow objective measurement for those who may themselves be unable to develop and assess achievement of values.

Modern wellbeing research

Modern wellbeing research has largely been undertaken within the field of psychology with a Western focus and many subjective measures of wellbeing. Some authors have extended the components of subjective wellbeing (SWB) to consist not only of positive and negative affect, but also the eudemonic component of life satisfaction (Diener, 1984).

Self-realisation theory (Waterman, 1993) describes experiences of ‘personal expressiveness’ that require intense involvement, have a special fit, make you feel alive and complete, as though the experience is what you are meant to do, and represents who you really are. Personal expressiveness echoes the eudemonia described by Aristotle. A similar eudemonic state is also described in flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 2008), which an individual experiences when they are engaged in achieving a goal, through integration of the senses, feelings and thoughts, and which leads to differentiation, as the individual feels more skilled.

Authentic happiness theory combines hedonist and eudemonist components: positive affect, engagement and meaning (Seligman, 2002). Seligman later replaced this with a theory containing five hedonist and eudemonist components: that is, positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment (‘PERMA’).

Hedonist and eudemonic components can be used to define wellbeing, but it should be noted that they interact. For example, Csikszentmihalyi found that ‘flow’ is more likely when an individual has a more positive affect (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2002); and King et al found that more meaning of life was reported when an individual had a more positive affect (King et al., 2006). Correlation may not be the only way that hedonist and eudemonic components interact. Reversal theory explores the ways by which humans switch between opposing motivations and describes them in four pairs of opposite states: the state of being motivated by a future goal (‘the Telic state’) and the state of being motivated by the enjoyment of the process (‘the Paratelic state’) comprise one of the four pairs (Apter, 2007). It may be therefore that we cannot experience hedonist and eudemonic components of wellbeing simultaneously, but instead fluctuate between them.

A definition of wellbeing should incorporate both the hedonist and eudemonic components of ‘positive feelings’ and ‘meeting full potential’, but should allow for either fluctuating or correlating interactions.

Differentiating components and determinants in modern psychology research

Identifying what is a component of wellbeing and what is a determinant of wellbeing is complex. In the field of Psychology, labelling components and determinants becomes even more challenging.

Ryff and Singers’ core dimension of psychological wellbeing (PWB) theory (Ryff & Singer, 2008) suggests the dimensions of psychological wellbeing are: self-acceptance, purpose in life, environmental mastery, positive relationships, personal growth and autonomy. These dimensions were utilised to develop the Ryff scale of PWB. Confirmatory factor analysis of scores on this scale from among Western populations (Ryff & Keyes, 1995) showed that the observed variables were related to the underlying theories of the fully functioning person, maturity, executive processes of personality, basic life tendencies, personal development, will to meaning, mental health and self-actualisation. The dimensions of psychological wellbeing described by Ryff and Singer describe different aspects of the eudemonic philosophy of ‘achieving full potential’: but are they each components in their own right?

International cultural and societal differences make using Ryff and Singers’ dimensions (Ryff & Singer, 2008) challenging. Autonomy, as an example, is an individualist concept. Immanuel Kant, during the Enlightenment, theorised that it is the capacity for autonomy that brings dignity as human beings (Mautner, 2000). By contrast, someone in Japan might say that it is our capacity for conformity that brings us dignity (Christopher, 1999). Confucius, who lived in China between 551 and 479 BCE, described individualism as:

‘. . .the fullest development by the individual of his creative potentialities - not, however, merely for the sake of self-expression but because he can thus fulfil that particular role which is his within the social nexus’. (Christopher, 1999)

His individualism was not about autonomy, but again about meeting full potential within society.

Deci and Ryans’ self-determination theory (SDT) also identifies autonomy among the dimensions of wellbeing, along with competence and relatedness (Ryan, 2000). Autonomy, relatedness and competence were also the three core needs of doctors identified in the UK General Medical Council report ‘Caring for doctors, caring for patients’ published just before the Covid-19 pandemic (West et al., 2019). Autonomy here is again at odds with the collectivist vision of the future doctor in the UK of being equally comfortable to be lead, as well as to lead (Health Education England, 2020a).

The pragmatic way forward would be to keep psychological dimensions labelled as potential determinants and not as essential components of wellbeing, as they go beyond the underpinning philosophies in a way that is not inclusive.

Concluding comments

This review demonstrates that an operational definition is needed to allow comparable measurement of wellbeing across different intellectual and geographical areas. The hedonistic term ‘positive feelings’ and the eudemonic term ‘meeting full potential as a member of society’ are inclusive, free from cultural bias and should be included in such a definition. The ability to measure wellbeing both subjectively and objectively should also be included in an operational definition. While overlapping with health, wellness, welfare and quality of life, wellbeing is separate to these nouns. Wellbeing is a holistic positive noun, and measurement adopting a salutogenic approach allows further differentiation of the concept from others. The operational definition proposed is not, therefore, limited to doctors, or the workplace, as a definition must allow for all determinants of wellbeing, whether generic, or specific to a particular group. Society is now global and is described in that way in this proposed definition: ‘Wellbeing is a state of positive feelings and meeting full potential in the world. It can be measured subjectively and objectively using a salutogenic approach’.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Health Education England (HEE) South has provided financial support for a postgraduate student fellowship for 3 years.

ORCID iD: Gemma Simons  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2454-5948

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2454-5948

References

- Apter M. J. (2007). Reversal theory: The dynamics of motivation, emotion and personality (2nd ed.). OneWorld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bart R., Ishak W. W., Ganjian S., Jaffer K. Y., Abdelmesseh M., Hanna S., Gohar Y., Azar G., Vanle B., Dang J., Danovitch I. (2018). The assessment and measurement of wellness in the clinical medical setting: A systematic review. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(9–10), 14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- British Medical Association. (2019). Caring for the mental health of the medical workforce. Author. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/workforce/mental-health-workforce-report [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge University Press. (2019). Online dictionary. Author. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/well-being [Google Scholar]

- Christopher J. C. (1999). Situating psychological well-being: Exploring the cultural roots of its theory and research. Journal of Counselling & Development, 77(2), 141–152. 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02434.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corey L. M. K. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M., Nakamura J. (2002). The concept of flow. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. (2008). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins R. A. (1998). The second approximation to an international standard for life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 43(3), 307–334. 10.1023/A:1006831107052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins R. A. (2010). Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(1), 1–17. 10.1007/s10902-009-9167-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Ryan K. (2009). Subjective Well-Being: A General Overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F008124630903900402 [Google Scholar]

- Dodge R. P., Daly A., Huyton J., Sanders L. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. 10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felce D., Perry J. (1995). Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 16(1), 51–74. 10.1016/0891-4222(94)00028-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable S. L., Haidt J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 103–110. 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Wellness Institute. (2020). What is wellness? Author. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/ [Google Scholar]

- Headey B., Veenhoven R., Wearing A. (1991). Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 81–100. 10.1007/BF00292652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Health Education England. (2020. a). The Future Doctor Programme. A co-created vision for the future clinical team. Author. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Future%20Doctor%20Co-Created%20Vision%20-%20FINAL%20%28typo%20corrected%29.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Health Education England. (2020. b). Wellness Inductions to all Interim Foundation Year 1 doctors during the Covid outbreak. Author. https://doctorstraining.com/2020/04/09/wellness/ [Google Scholar]

- Hogan M. J., Johnston H., Broome B., McMoreland C., Walsh J., Smale B., Duggan J., Andriessen J., Leyden K. V., Domegan C., McHugh P., Hogan V., Harney O., Groarke J., Noone C., Groarke A. M. (2015). Consulting with citizens in the design of wellbeing measures and policies: Lessons from a systems science application. Social Indicators Research, 123(3), 857–877. 10.1007/s11205-014-0764-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang E. C. H. (2019). Resident burnout in Taiwan Hospitals-and its relation to physician felt trust from patients. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 118(10), 1438–1449. 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S. M. (1997). Editorial: The problem of quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 6(3), 205–212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4035081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan T. B., Biswas-Diener R., King L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 219–233. 10.1080/17439760802303044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King L. A., Hicks J. A., Krull J. L., Del Gaiso A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179–196. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley P. C., McKenna S. P. (2021). Fundamental Measurement: The Need fulfilment Quality of Life (N-QOL) measure. Innovations in Pharmacy, 12(2), 6. 10.24926/iip.v12i2.3798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Duckworth A., Steen T. A., Seligman M. E. (2004). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 629–651. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margiotta F. (2019). Prevalence and co-variates of burnout in consultant hospital doctors: Burnout in consultants in Ireland Study (BICDIS). Irish Journal of Medical Science, 188(2), 355–364. 10.1007/s11845-018-1886-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautner T. (2000). The penguin dictionary of philosophy. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mind. (2020). Support your team and yourself with our free Guides to Wellness Action Plans. https://www.mind.org.uk/workplace/mental-health-at-work/taking-care-of-yourself/guide-to-wellness-action-plans-employees/

- Nussbaum M. C. (2000). Women and Human Development. The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. (2011). Measuring what matters. National statisticians’ reflections on the national debate on measuring national well-being. Author. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/national-wellbeing [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. (2015). Personal wellbeing in the UK 2014/15. Office for National Statisttics. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105171535/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/wellbeing/measuring-national-well-being/personal-well-being-in-the-uk--2014-15/stb-personal-well-being-in-the-uk--2014-15.html

- Robeyns I. (2005). The capability approach: A theoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 93–117. 10.1080/146498805200034266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. B. T., James O. P., Hopkins L., Brown C., Bowman C., Abdelrahman T., Pollitt M. J., Egan R. J., Bailey D. M., Lewis W. G. (2019). Stress and burnout in training; Requiem for the surgical dream. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(1), e1–e8. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. M., Deci E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. D., Keyes C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. D., Singer B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. (2005). Human rights and capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 6(2), 151–166. 10.1080/14649880500120491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Warner D. O., Macario A., Zhou Y., Culley D. J., Keegan M. T. (2019). Repeated cross-sectional surveys of burnout, distress, and depression among anesthesiology residents and first-year graduates. Anesthesiology, 131(3), 668–677. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarkiewicz W. (1976). Analysis of happiness (Vol. 3). Melbourne International Philosphy Series. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik D. S., Profit J., Morgenthaler T. I., Satele D. V., Sinsky C. A., Dyrbye L. N., Tutty M. A., West C. P., Shanafelt T. D. (2018). Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93(11), 1571–1580. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik M. H., Carlquist E. (2017). Measuring subjective well-being for policy purposes: The example of well-being indicators in the WHO “Health 2020” framework. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(2), 279–286. 10.1177/1403494817724952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman A. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678–691. 10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West M C. D. (2019). Caring for doctors, caring for patients. How to transform UK healthcare environments to support doctors and medical students to care for patients. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/caring-for-doctors-caring-for-patients_pdf-80706341.pdf

- World Health Organisation. (1948). Preamble to the Constitution of WHO as adopted by the International Health Conference. Author. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hist/official_records/constitution.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2018). International Classification of Diseases 11 for morbidity and mortality statistics. World Health Organisation. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/12918028

- World Health Organisation. (2020). WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Author. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yates M., Samuel V. (2019). Burnout in oncologists and associated factors: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(3), 1–19. 10.1111/ecc.13094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]