ABSTRACT.

Neurotuberculosis (NT) continues to be a global health problem with severe morbidity and mortality. The manifestations of NT are well-known and encompass forms such as meningitis, tuberculomas, military tuberculosis, ventriculitis, and brain abscess. Data of all patients with central nervous system tuberculosis who underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) were analyzed. Over a 7-year period (2014–2021), we encountered three patients who had dense neurological deficits and 18F-FDG PET-CT results suggesting focal cortical encephalitis. 18F-FDG PET-CT demonstrated focal hypermetabolism involving focal–regional areas of the left hemisphere that corresponded to clinical deficits in two of the three patients. Follow-up 18F-FDG PET-CT showed improvement in cortical hypermetabolism in all three patients that corresponded with clinical improvement. MRI of the brain with contrast showed subtle leptomeningeal enhancement in these areas, along with other features of NT, but it could not detect cortical involvement. A literature review also revealed some previous descriptions that seemed to be consistent with tuberculous encephalitis (TbE). TbE seems to be a distinct subset of NT and may coexist with other features of NT or disseminated tuberculosis. It may be detected by 18F-FDG PET-CT even when brain MRI does not show any evident abnormality to explain a focal neurological deficit. 18F-FDG PET-CT can be considered during the evaluation and monitoring of NT to detect TbE. The presence of TbE may affect the prognosis and treatment duration of NT.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis is rampant in developing countries and causes between 110 and 165 cases per 100,000 individuals in the population, which is more than 10- to 15-times the rate of developed countries.1 Of these cases, approximately 10% are attributable to extrapulmonary causes. Tuberculous meningitis is a common cause of chronic meningitis in India and results in tremendous morbidity and mortality. The most well-known forms of central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis include meningitis, tuberculomas, military tuberculosis, ventriculitis, brain abscess, spinal epidural abscess, spinal tuberculoma, radiculomyelitis, and arachnoiditis.

Coinfection with HIV results in a higher disease burden and worse outcomes. With the advent of antiretroviral therapy, new treatment-related complications such as tuberculosis–immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (TB-IRIS) have been discovered.2 Paradoxical TB-IRIS is the most well-known form of TB-IRIS and occurs in approximately 4 to 54% of patients coinfected with tuberculosis and HIV. CNS paradoxical TB-IRIS is diagnosed when IRIS develops within 3 months of antiretroviral therapy initiation. Patients who have been previously diagnosed with tuberculosis have shown a good initial response to treatment. However, the subsequent development of TB-IRIS results in new manifestations or worsening of the ongoing illness.

Tuberculous encephalopathy was described in 1970 in the pediatric population and ascribed to an immune-mediated reaction.3 These patients had multiple hyperintense symmetrical lesions in the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres on T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), with some diffusion restriction and minimal postcontrast enhancement. Tuberculosis encephalopathy has been characterized by diffuse brain edema and demyelination with microvascular necrosis, perivascular macrophage reaction, demyelination and glial nodules in the white matter. Clinical features include altered sensorium, seizures, and other features with or without cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) changes. However, this entity is no longer reported.

CNS tuberculosis predominantly presents with meningitis, tuberculomas, or other complications. With the increasing use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT), infective or inflammatory foci that are undetectable on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be detected in CNS tuberculosis.4 Tuberculosis encephalitis (TbE) is such an entity that can be detected by 18F-FDG PET-CT. We have previously reported TbE in a young girl who required more than 2.5 years of anti-tuberculous therapy (ATT) and continues to be mute and disabled even after being “cured.” During the past 7 years, we have encountered two more cases of TbE. All three cases occurred in individuals without HIV. TbE is a rare manifestation of CNS tuberculosis that may possibly increase morbidity and mortality. The aim of this study was to characterize and describe the 18F-FDG PET-CT findings of TbE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed the medical records of all patients with CNS tuberculosis examined at Aster Medcity, Kochi, Kerala, India, from 2014 to 2021. Of the total of 37 patients, all had undergone brain MRI with contrast at least once, and nine patients had undergone 18F-FDG PET-CT. Of these nine patients, three patients demonstrated focal cortical involvement on 18F-FDG PET-CT in addition to other findings of neurotuberculosis. Ethics committee approval was obtained from our institution; informed patient consent was also obtained. Based on our previous work, we hypothesized that some patients could have TbE that may not be detectable on MRI alone.5 Patients were followed-up during periodic outpatient visits, inpatient rehabilitation, or by telephonic enquiries.

The following predetermined diagnostic criteria for TbE were established: cases fulfill the international encephalitis consortium criteria for encephalitis6 (Table 1); cases are confirmed as TbE if CSF PCR, GeneExpert, or culture results are positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis or probable TbE when Mycobacterium tuberculosis is isolated in a sample other than CSF; cortical changes on MRI or foci of hypermetabolism on 18F-FDG PET-CT not compatible with infarction, tuberculoma, or tuberculous abscesses; negative paraneoplastic and neuronal autoantibody workup and HIV serology results; and focal deficit attributable to the MRI or PET-CT findings.

Table 1.

Cases of probable tuberculous encephalitis described in literature

| Author | Patient age | Presentation | Diagnostic tests | Imaging findings | PET-CT | Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toudou Daouda, 201724 | 53 years | Altered sensorium, memory deficits | CSF results were negative Diagnosis was presumptive Brain biopsy was not performed |

MRI showed features of limbic encephalitis (bilateral basifrontal and mesial temporal hyperintensities) with nodular contrast enhancement of these lesions with overlying leptomeningeal thickening | Not performed | Complete recovery | Limbic encephalitis caused by neurotuberculosis (TbE) |

| Daher et al. 201925 | 42 years | Altered mental status | CSF was not performed Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) revealed Mycobacterium tuberculosis Diagnosis of TbE was presumptive Brain biopsy was not performed |

MRI suggestive of limbic encephalitis (left hippocampal, amygdalar hyperintensities) with multiple small scattered tuberculomas | Not performed | Good recovery | Limbic encephalitis caused by neurotuberculosis (TbE) |

| Sonkaya et al. 201426 | 53 years | Headache, memory impairment, crying, and gait disturbance |

CSF results were normal Inguinal node biopsy results showed caseating granulomas Brain biopsy was not performed |

MRI suggestive of limbic encephalitis with FLAIR hyperintensities in the bilateral temporal lobes Cerebellar tuberculomas |

Focal hypermetabolism in the left frontal and left parieto-occipital regions of the brain |

Improvement | Coincidental, probably paraneoplastic in evolution |

| Gambhir et al. 201627 | 30 years | None | CSF TB PCR results were positive Brain biopsy was not performed |

Normal | FDG-avid lesion right cerebellar cortex | Good | Not mentioned |

| Tomar et al. 202128 | 20 years | Left sixth nerve palsy with bilateral gaze-evoked nystagmus | CSF examination revealed a cell count of 32/μL, lymphocytic predominance (98%), protein of 88.6 mg/dL, and glucose of 55.5 mg/dL AFB stain and CSF GeneExpert results were negative for TB FNAC of the mediastinal lymph node revealed multiple epithelioid cell granulomas with reactive lymphoid cells and positive AFB results Brain biopsy was not performed |

Brain MRI without contrast enhancement showed hyperintensity in the bilateral internal capsule and homogeneous diffuse hyperintensity in the midbrain, pons, medulla, and left side of the cerebellum | Not performed | Complete recovery | Tubercular rhombencephalitis |

AFB = acid-fast bacilli; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; EBUS-TBNA = endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration; FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose; FLAIR = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; FNAC = fine-needle aspiration cytology; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PET-CT = positron emission tomography–computed tomography; TB = tuberculosis; TbE = tuberculous encephalitis.

PET-CT was performed using a Siemens biograph horizon time-of-flight PET-CT machine after injecting 8 millicuries of 18F-FDG intravenously during euglycemic status. Whole-body PET-CT was acquired after 50 minutes, and the images were analyzed by a trained nuclear medicine specialist. We also reviewed the literature and found other cases with similar MRI or PET-CT findings compatible with a diagnosis of focal TbE.

Case 1.

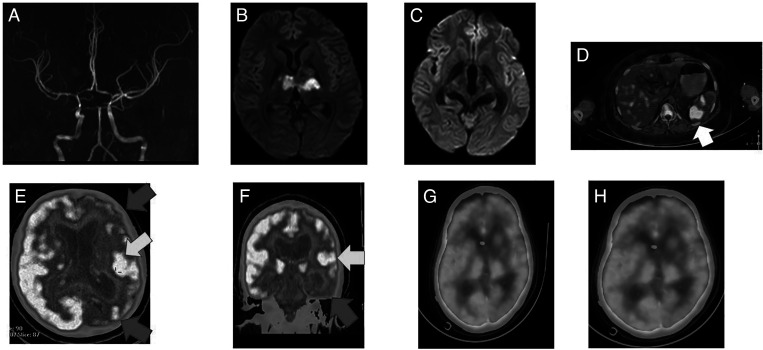

A 17-year-old girl presented with acute onset of difficulty speaking. Examination revealed severe effortful speech, articulatory groping, and buccofacial apraxia with preserved verbal comprehension, reading, and writing suggestive of apraxia of speech. Possible neurosarcoidosis had been diagnosed 8 months previously, when MRI showed a left medial occipital lobe and petrous temporal ring-enhancing lesion. CSF examination results were normal at that time, and steroid therapy (prednisolone 30–45 mg/day) was started. After 8 months of therapy, a repeat brain MRI with contrast showed no new changes. Repeat CSF examination showed 45 cells (100% lymphocytes) with normal sugar levels and protein of 75 mg%. However, electroencephalography (EEG) showed left hemispheric slowing, and she was administered intravenous levetiracetam and sodium valproate for presumed epileptic aphasia. When continuous EEG monitoring for 4 days showed only left hemispheric slowing without any epileptiform discharges and persistent aphemia, 18F-FDG PET-CT was ordered. 18F-FDG PET/CT showed FDG-avid adenoid tissue, avid splenic lesions, and a sacral lytic lesion. There was diffuse FDG uptake with a hypermetabolic focus in the left operculum and anterior cingulate gyrus (Figure 1). Adenoid and sacral lesion biopsy using acid-fast bacilli and GeneExpert indicated results positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was started on five-drug ATT (rifampicin, INH, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide [RHEZ] + moxifloxacin) with steroids. After 18 months of treatment, MRI showed decreased enhancement around the suprasellar cistern (without any opercular changes), and PET-CT showed diffuse left hemispheric hypometabolism. She continued ATT for 24 months. She remains ambulant with persistent apraxia of speech. At the 30-month follow-up evaluation, repeat PET-CT showed persistent left cerebral hemispheric hypometabolism and brain MRI results were normal.

Case 2.

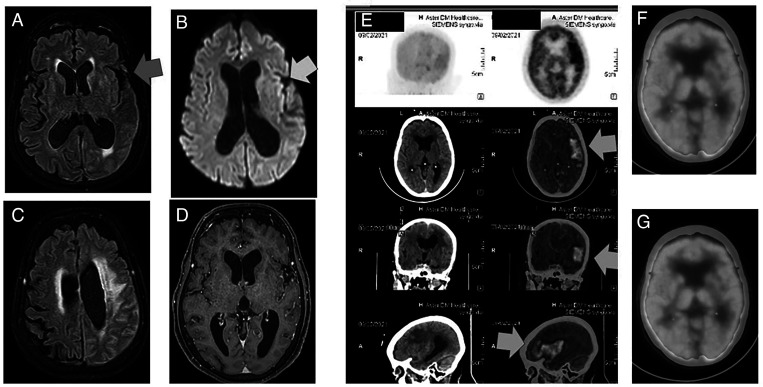

A 70-year-old woman with diabetes and hypothyroidism presented with generalized weakness and fever for a duration of 3 weeks, followed by dysphagia and dragging of the right leg while walking. After admission for evaluation of dysphagia, she became mute and bedbound. When she was evaluated with 18F-FDG PET-CT for fever of unknown origin, the results showed asymmetric diffuse increased FDG uptake in the left frontotemporal area and multiple, large FDG-avid para-aortic lymph nodes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) axial image showing very subtle sulcal effacement in the left temporal lobe (blue arrow). (B) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWMRI) shows subtle left insular diffusion restriction (yellow arrow). (C) FLAIR axial image showing subcortical white matter edema. (D) Axial contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows subtle leptomeningeal enhancement (blue arrow). (E) Axial, sagittal, and coronal 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) images showing left frontal and frontotemporal lobe and insular hypermetabolism (orange arrows) corresponding to the computed tomography (CT) images detected effaced sulcal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces with enhancement along the left frontotemporal cerebral sulci and along the left tentorium cerebelli (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax], 7.8). (F and G) Resolution of left frontotemporal lobe and insular hypermetabolism and replacement by hypometabolism. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 1.

(A) Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) sequences showing attenuated intracranial vessels suggestive of tuberculous vasculitis. (B) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWMRI) showing bithalamic infarctions caused by optochiasmatic arachnoiditis and tuberculous endarteritis. (C) DWMRI showing subtle scattered tiny infarcts in both opercular areas. (D) Axial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) images showing a large splenic avid lesion (white arrow). (E) 18F-FDG PET-CT showing left hemispheric hypermetabolic (yellow arrow) and hypometabolic areas (red arrows). (F and G) Resolution of the left frontotemporal lobe and insular hypermetabolism and replacement by hypometabolism. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 3.

(A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) axial images showing ventriculomegaly with normal cortex. (B) Axial T1 contrast MRI showing subtle interhemispheric leptomeningeal enhancement. (C, D, and E) Axial, sagittal, and coronal positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) images showing diffuse left frontotemporal cortical hypermetabolism (yellow arrows) (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax], 11.2). (E) Axial PET-CT image showing basal hypermetabolism corresponding to optochiasmatic arachnoiditis. (F, G, and H) Axial PET-CT images showing persistent optochiasmatic arachnoiditis (blue arrow) with resolution of frontotemporal cortical hypermetabolism (yellow arrow). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Examination revealed global aphasia and dense right hemiplegia. MRI revealed subtle restricted diffusion in the insular cortex. There was minimal leptomeningeal enhancement in the left sylvian fissure and parietal sulci. CSF examination showed 75 cells with 100% lymphocytes, normal sugar, and protein of 87 mg%. CSF GeneExpert results were positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A final diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis with left focal frontotemporal TbE was made, and she was started on four-drug ATT with steroids (Dexamethasone 8 mg/day). However, her treatment was switched to two-drug ATT after a second PET-CT on day 60 showed resolution of hypermetabolism.

Case 3.

A 36-year-old woman presented with exertional dyspnea for the past 4 months. CT of the thorax showed multiple enlarged supraclavicular and mediastinal lymph nodes and infiltrates in the right lung. The supraclavicular lymph node biopsy results indicated caseating granulomas. She was started on four-drug ATT. On day 4, headache developed and rapidly worsened, and she required intubation. Brain CT showed multiple scattered tuberculomas in both hemispheres and capsuloganglionic regions with hydrocephalus. An external ventricular drain was inserted. Brain MRI showed multiple infarcts with multiple tuberculomas and features of optochiasmatic arachnoiditis, leptomeningeal enhancement, and multiple infarcts. The initial CSF examination results were normal, and cultures and tuberculosis diagnostic panel results were negative. One week later, repeat MRI showed multiple new infarcts secondary to endarteritis. Antiplatelets were started. At that point, she was stuporous, with right oculomotor palsy and bilateral spastic quadriparesis. A ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed. However, she became comatose. On day 45, 18FDG- PET CT showed abnormal increased FDG uptake within the thick enhancing exudates in the basal cisterns and left sylvian fissure. There was a large area of focal cortical hypermetabolism involving the left temporo-occipital cortex (maximum standardized uptake value, 11.2). A diagnosis of additional focal temporo-occipital TbE was considered (Figure 2). Dexamethasone 8 mg/day was added for 2 months. On day 90, repeat PET-CT showed resolution of the focal hypermetabolism with diffuse holocerebral hypometabolism. Her clinical status improved and she was able to stand with support, say her name, and follow simple commands. She has been using ATT for 130 days and continues to participate in follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Microglia are the primary CNS cells infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but astrocytes and neurons are also involved to a lesser extent. Compared with 76% of microglia that contain approximately four bacilli per cell, only approximately 15% of astrocytes are infected and have a lower bacterial load of approximately 1.3 bacilli per cell.7 Microglial internalization of tuberculosis bacillus in humans leads to activation of these immune cells, secretion of cytokines, other inflammatory mediators, and further influx of inflammatory cells. T-helper cells (Th1 type) secrete interferon-γ and interleukin-2. Interferon-γ stimulates macrophage transformation to giant cells that wall-off tuberculosis bacilli by forming a reactive granuloma. Therefore, tuberculomas that are conglomerate caseous foci with a rim of connective tissue of reticulin fibers (capsule), fibroblasts, epithelioid cells (that merge to form Langhans giant cells), and lymphocytes develop within the brain parenchyma.

Lesser degrees of the host immune response can lead to the development of focal cerebritis (tuberculosis cerebritis) or a tuberculous abscess, both of which may contain viable tuberculosis bacilli. Tuberculosis abscesses are encapsulated collections of pus that contain viable tubercular bacilli and lack typical granulomatous features.8 Tuberculosis cerebritis is characterized by a focal, ill-defined area of involvement of the cerebral parenchyma. Histologically, these lesions contain microgranuloma, lymphocytic infiltrates, Langhans giant cells, epithelioid cells, and rare tubercle bacilli. MRI is useful for demonstrating characteristic features of tuberculosis cerebritis such as a focal area of a high T2/FLAIR signal in the parenchyma with gyral swelling and enhancement with adjoining leptomeningeal enhancement. Contrast studies show intense lesional enhancement with varying amounts of diffusion restriction.9 Das et al. described two patients with diffuse subcortical white matter FLAIR hyperintensities and extensive hyperintensities in the brainstem and cerebellar peduncles with focal periventricular and subcortical white matter involvement, which closely resemble TbE.10 These cases did not show any diffusion restriction; however, there was extensive punctate contrast enhancement within these lesions favoring tuberculosis cerebritis.

The predilection of tuberculous meningitis involving the basal cisterns results in the immersion of the hypothalamus and pituitary stalk in an infective and inflammatory mixture that results in a wide variety of neuroendocrine-associated metabolic abnormalities (gonadotropin deficiency, hyperprolactinemia, thyrotropin deficiency, corticotropin deficiency, somatotropic hormone deficiency, and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone or cerebral salt wasting) in tuberculosis meningitis. Basal exudates produce neuronal edema, perivascular infiltration, and microglial reactions. Extension of this exudate along small neoangiogenic proliferating blood vessels into the brain parenchyma has been described as “border zone” encephalitis; however, these are actually focal ischemic brain changes caused by vasculitis.11,12 Hence, these cases are not true TbE and show cerebral infarction or edema changes in regions that are in close relation to basal exudates such as the sylvian fissure, basal forebrain, or brainstem.13

When cellular immunity is compromised or deficient, such as with diabetes mellitus, AIDS, chronic glucocorticoid, more extreme dissemination of tuberculosis bacillus can result in tuberculous meningitis and disseminated tuberculosis. In such situations, diffuse infiltration of tuberculosis bacillus into the cerebral parenchyma and contiguous tissue spread may also lead to TbE.

TbE, as defined by our criteria, is extremely unusual. Although the term has been used freely in the literature, only five cases that actually fit the criteria for TbE have been reported: three with limbic encephalitis, one with cerebellitis, and one with rhombencephalitis.14,15 None of these cases underwent brain biopsy to prove the diagnosis. Although tuberculosis rhombencephalitis has been described with AIDS in a few cases, these cases mainly involved multiple brainstem tuberculomas with leptomeningeal enhancement and were not true TbE.

A large series of TbE cases in France was published in 2013.16 However, the authors included all variants of neurotuberculosis, including tuberculomas, arachnoiditis, and hydrocephalus. Imaging results were normal for nearly 50% of patients, and pure TbE were not seen in this cohort. Moragas et al.17 also published a large series of 97 patients with rhombencephalitis. Among these patients, two had tuberculosis; however, imaging details were not provided in the article. Two of our patients had disseminated tuberculosis and presented with TbE before steroids were initiated, whereas the index patient had received high-dose steroids for prolonged periods (8 months), followed by presentation with TbE. Therefore, a primary or secondary impaired host immune response might have been crucial to the development of TbE.

18F-FDG PET/CT is useful for diagnosing of CNS infections or inflammatory conditions, and it is often used for the evaluation of autoimmune encephalitis.18 FDG-PET/CT has better sensitivity than MRI for the diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis, with a sensitivity of 85 to 87% compared with EEG (30%), MRI (40%), and CSF abnormalities (62%). FDG patterns include isolated hypometabolism in 70%, isolated hypermetabolism (3%), or a mixture of hypermetabolic and hypometabolic areas (13%). Approximately 25% demonstrate basal ganglia hypermetabolism. Isolated basal ganglia hypermetabolism is seen in approximately 50% of patients with leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 encephalitis with faciobrachial dystonic seizures.19 Only a minority (15%) have normal brain FDG and PET-CT results.20 In some series, the sensitivity of FDG and PET-CT was as high as 95% compared with MRI (40%).21

With autoimmune encephalitis, such as N-methyl D-aspartate receptors encephalitis, a mixture of hypermetabolism and hypometabolism is encountered. Characteristic 18F-FDG PET-CT findings include medial occipital lobe hypometabolism, and progressive resolution of lateral and medial occipital hypometabolism correlates with improvements in the neurologic status of patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.11

There have been few studies of 18F-FDG PET-CT for infectious encephalitis. With infectious encephalitis, increased tissue uptake of 18F-FDG is caused by hypercellularity, overexpression of GLUT-1 and GLUT-3 transporter isotypes, and increased hexokinase activity. 18F-FDG also accumulates in inflammatory cells such as neutrophils, activated macrophages, and lymphocytes at sites of inflammation or infection. Tuberculomas show a ring-like or “doughnut” pattern, with low uptake within the abscess cavity and peripheral increased uptake.22 In a series of 10 patients with tuberculous meningitis, 18F-FDG PET-CT results were abnormal for 70% of patients, whereas contrast MRI results were abnormal for 90%. However, whole-body PET-CT increased the sensitivity to 100% by demonstrating extracranial sites where confirmatory biopsies could be performed.4

All our patients exhibited focal cortical hypermetabolism that showed improvement on serial PET-CT imaging. 18F-FDG PET-CT showed focal encephalitis in areas that were essentially normal or that showed only mild leptomeningeal enhancement on MRI. We could not conclusively rule out underlying cerebral infarction secondary to vasculitis resulting from tuberculosis encephalitis. However, the persistent focal hypermetabolism shown by 18F-FDG PET-CT with minimal changes on MRI were unusual. All our patients had disseminated tuberculosis; for two patients, 18F-FDG PET-CT detected TbE as the first neurological manifestation of the disease.

Although it is likely that patients with disseminated tuberculosis are predisposed to develop TbE, and because 18F-FDG PET-CT may help detect TbE in selected cases, our data may not be generalizable to larger populations because our sample size was small. Moreover, the huge costs associated with repeated 18F-FDG PET-CT studies as well as restricted availability of PET-CT centers in developing countries where neurotuberculosis has the highest incidence are obstacles to widespread testing.23 Although the 18F-FDG PET-CT image results of our patients were consistent with a diagnosis of encephalitis, the findings by themselves cannot prove the diagnosis of TbE. Brain biopsy is the gold standard for truly demonstrating the pathological features of TbE. Other conditions such as immune-mediated demyelination (acute disseminated encephalitis) or immune-mediated phenomena may be considered in the differential diagnosis; however, the clinical picture and essentially normal MRI findings in the area with FDG hypermetabolism make these entities less likely than primary infectious encephalitis.

In conclusion, 18F-FDG PET/CT may be superior to brain MRI for detecting TbE, especially if patients have neurological deficits that are unexplained by MRI or disseminated tuberculosis. Focal cortical hypermetabolism without an underlying structural lesion on MRI with neurotuberculosis should prompt the consideration of TbE. 18F-FDG PET-CT may also be useful for assessing the treatment response of tuberculosis. TbE appears to be a distinct subset of neurotuberculosis that may coexist with other clinical and imaging features of neurotuberculosis, and it may influence the morbidity, prognosis, and treatment duration of neurotuberculosis. Other factors, such as the utility of 18F-FDG PET-CT for modifying the ATT regimen or duration when TbE is detected, require further exploration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1. Raviglione MC, Snider DE, Kochi A, 1995. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Morbidity and mortality of a world wide epidemic. JAMA 273: 220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn CM. et al. , 2020. Tuberculosis IRIS: pathogenesis, presentation, and management across the spectrum of disease. Life (Basel) 10: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Udani PM, Dastur DK, 1970. Tuberculous encephalopathy with and without meningitis. Clinical features and pathological correlations. J Neurol Sci 10: 541–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gambhir S, Kumar M, Ravina M, Bhoi SK, Kalita J, Misra UK, 2016. Role of 18F-FDG PET in demonstrating disease burden in patients with tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Sci 370: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maramattom BV, Thomas J, Joseph S, 2019. Tuberculous encephalitis with aphemia detected only by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 22: 527–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Venkatesan A. et al. , 2013. Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: consensus statement of the international encephalitis consortium. Clin Infect Dis 57: 1114–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rock RB. et al. , 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced cytokine and chemokine expression by human microglia and astrocytes: effects of dexamethasone. J Infect Dis 192: 2054–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumar R, Pandey CK, Bose N, Sahay S, 2002. Tuberculous brain abscess: clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment (in children). Childs Nerv Syst 18: 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jinkins JR, 1988. Focal tuberculous cerebritis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 9: 121–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das A, Pradhan S, 2019. Diffuse tuberculous cerebritis in immunocompetent hosts-an uncommon entity. J Clin Diagn Res 13. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2019/40334.12637. [DOI]

- 11. Davis AG, Rohlwink UK, Proust A, Figaji AA, Wilkinson RJ, 2019. The pathogenesis of tuberculous meningitis. J Leukoc Biol 105: 267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dastur DK, Manghani DK, Udani PM, 1995. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms in neurotuberculosis. Radiol Clin North Am 33: 733–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Modi M, Goyal MK, Jain A, Sawhney SS, Sharma K, Vyas S, Ahuja CK, 2018. Tuberculous meningitis: challenges in diagnosis and management: lessons learnt from Prof. Dastur’s article published in 1970. Neurol India 66: 1550–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomar LR, Shah DJ, Agarwal P, Rohatgi A, Agarwal CS, 2021. Tubercular rhombencephalitis: a clinical challenge. Ann Indian Acad Neurol (ePub ahead of print). doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_685_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Sahaiu-Srivastava S, Jones B, 2008. Brainstem tuberculoma in the immunocompetent: case report and literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 110: 302–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Honnorat E, De Broucker T, Mailles A, Stahl JP, 2013. le comité de pilotage et groupe des investigateurs. Encephalitis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in France. Med Mal Infect 43: 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moragas M, Martínez-Yélamos S, Majós C, Fernández-Viladrich P, Rubio F, Arbizu T, 2011. Rhombencephalitis: a series of 97 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 90: 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Bordonne M. et al. , 2021. Brain 18F-FDG PET for the diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu X. et al. , 2020. The clinical value of 18F-FDG-PET in autoimmune encephalitis associated with LGI1 antibody. Front Neurol 11: 418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Probasco JC, Solnes L, Nalluri A, Cohen J, Jones KM, Zan E, Javadi MS, Venkatesan A, 2017. Abnormal brain metabolism on FDG-PET/CT is a common early finding in autoimmune encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 11: e352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solnes LB. et al. , 2017. Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT versus MRI in the setting of antibody-specific autoimmune encephalitis. J Nucl Med 58: 1307–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu M, Lu L, Liu Q, Bai Y, Dong A, 2021. FDG PET/CT in disseminated intracranial and intramedullary spinal cord tuberculomas. Clin Nucl Med 46: 266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Skoura E, Zumla A, Bomanji J, 2015. Imaging in tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis 32: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Toudou Daouda M, Obenda NS, Souirti Z, 2017. Tuberculous limbic encephalitis: a case report. Med Mal Infect 47: 352–355. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Daher JA, Monzer HT, Abi-Saleh WJ, 2019. Limbic encephalitis associated with tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenitis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 18: 100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Sonkaya A, Senol M, Demir S, Kendirli M, Sivrioglu A, Haholu A, Ozdag M, n.d. Limbic encephalitis association with tuberculosis: a case report. Dis Mol Med 2: 73.

- 27. Gambhir S, Kumar M, Ravina M, Bhoi SK, Kalita J, Misra UK, 2016. Role of 18F-FDG PET in demonstrating disease burden in patients with tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Sci 370: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28. Tomar LR, Shah DJ, Agarwal P, Rohatgi A, Agarwal CS, 2021. Tubercular rhombencephalitis: a clinical challenge. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology (ePub ahead of print). DOI: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_685_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]